What happens when we reopen the ear, not only as a site of perception, but as a threshold for memory, identity, and transformation? How might deep, embodied listening allow us to access the invisible architectures that shape who we are, internal time, ritual, spiritual resonance, and reorient us toward a more fluid, post-human understanding of self? In a world saturated by visual dominance and extraction logics, can listening become a quiet form of resistance, a way to transmit emotion, reimagine presence, and dissolve boundaries between body, landscape, technology, and the unknown?

This is a powerful question. One that opens up deep research into the nature of perception. We often forget just how dominant sight is in our culture. I’m someone who constantly records, both sound and image, and I’ve noticed something essential through field recording, particularly in nature. When I’m focused on video, my brain is busy: framing, composing, evaluating. But with sound, it’s different. Listening taps me into the present. It brings the moment into the body.

The eyes face forward; they frame and judge. The ears, on the other hand, are lateral. They open you up and make you porous to your surroundings. Listening inherently invites connection. When you’re truly listening, your body becomes part of the environment. It’s no longer about observation from a distance. It becomes participation. Even in conversation, when we only look, we risk staying on the surface and falling into judgment. But when we listen, we extend ourselves toward the other. We meet them. There’s something beautifully shared in listening. It’s a relational act: between you and another, you and the world, you and yourself.

You often work with voices that seem to arrive from somewhere distant or unknown: dislocated, layered, multiplied. What draws you to this fragmentation of the voice, and how does it reflect your relationship with space, memory, or selfhood?

I remember, even without a formal background in music or opera, how deeply moved I was by a moment in the opera in Belgium. A voice sang from offstage, unseen and disembodied. It drifted in like a phantom, and I found it to be the most powerful part of the entire performance. I later learned it’s a known technique, but the effect was profound. There’s something magical in the distant voice. Softness, absence, or quiet can activate more imagination than what is overt.

I’ve had similar moments while walking through cities such as Poland, France, and Austria, where I’d catch traces of a rehearsal through a building window. A faint opera voice or instrument barely reaching my ears. It’s often too soft to record, and too ethereal to locate. But I’d stop in my tracks, completely captivated. These fragile, fleeting moments, blended with city sounds, become living compositions that exist only in that time and place. They’ve deeply influenced how I approach mixing and composing today.

And again, it’s about presence. Anyone can experience this. You don’t need special training or tools. All it takes is noticing. Simply listening. It cuts through so much noise about who’s allowed to be a composer, or what counts as music. When you open yourself to the everyday as potential composition, it becomes a kind of liberation.

But in the rush of daily life, we often forget to listen. These small, shimmering moments slip by unnoticed. And yet, through music, through the act of deeply listening, we can return to them. Your work, your sound, has the power to bring us back. To remind us of the beauty in the everyday. That sense of wonder. The magic that still lives in the ordinary. It’s like rediscovering a kind of childlike joy. Brief, but real, and deeply human.

In your recent works, sound feels like a portal — opening onto spaces that are emotional, psychic, even elemental. What role do liminal states, deep listening, or field recording play in helping you access what’s beyond the visible or the tangible?

For me, sound is a gateway to altered states of consciousness. Deep, embodied listening helps me step outside the dominance of visual perception that’s so present in daily life. When I really focus on the auditory, I find I can access something quieter — internal rhythms, spiritual resonances, a more profound connection to place and presence.

Much of your work resists overt structure, yet it carries an undeniable sense of coherence — as if guided by internal tides. How do intuition, ritual, or bodily memory shape your compositional process? What’s happening beneath the form?

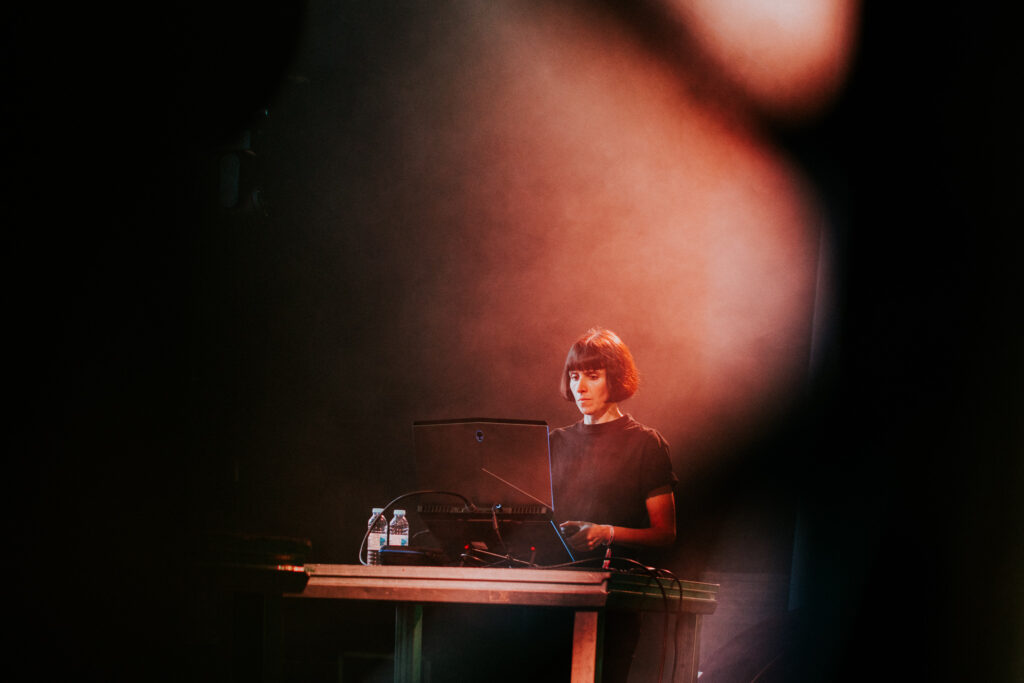

Intuition plays a central role. My process is entirely guided by feeling, an internal sense of knowing, step by step, what needs to happen next. When I’m working with recorded sounds and assembling a composition in the software, it’s never about formulas or rules. It’s always about what feels right. I listen, and something in me knows. This needs to be softened. That has to be removed. This transition matters. It’s a visceral process.

Time is also a crucial part of it. You can get very deep into something, but eventually you have to let it go. Step away. Forget it for a while. And then, when you return, intuition steps in again with fresh ears. That space in between, forgetting and returning, becomes part of the composition itself. It’s almost like a ritual of death and rediscovery.

I don’t build pieces using traditional musical structures. No bars, no beats. I don’t even open those grids in the software. I avoid anything that might constrain the process into something too rigid. Instead, I work in a kind of open time. Structureless, but not directionless.

And yet, as you noted, there’s coherence. It emerges through listening, through the way it feels to me as a listener. That embodied sense of rhythm and progression creates its own kind of form. So while I may resist overt structures, the shape of the piece arises from inside. It comes from intuition, ritual, and the memory held in the body.

Your work often stretches time until it almost dissolves. What kind of consciousness emerges in that expanded space? How does temporal distortion help you access emotional or spiritual dimensions in your practice?

I often hear the same comment after a concert: “I thought that was an hour, but it was only twenty minutes.” Or the opposite: “I can’t believe that much time passed.” People are surprised by how elastic time feels. They’re curious about the actual duration, because what they experienced was something completely different. To me, that’s a profound compliment.

When I’m working on music and I lose track of time myself, I take that as a sign I’m in the right place. That kind of absorption is a gift. In daily life, we’re so bound by time, by schedules, by structure. But to enter a space where time slips away, like having a picnic and suddenly it’s dusk without realizing it, that’s rare and precious.

You asked about consciousness in this expanded space, and I think it’s something close to dream logic. In dreams, fragments of memory, emotion, and experience collide in strange, surreal ways. And yet, sometimes a dream leaves you with a distinct clarity. Like it answered a question you didn’t even know how to ask. Music can work in that same way. It reaches beyond language or linear thought and allows for a kind of emotional resolution, or even healing, that bypasses rational understanding.

Letting go of structured time and logical sequencing opens a portal. In that temporal suspension, you can access deeper layers: emotional, spiritual, unconscious. I think that’s why music has always been part of ceremony and healing. It creates a space where we can feel something shift, release, or clarify, without needing to explain why.

So yes, stretching or dissolving time isn’t just a stylistic choice. It’s a way to enter another kind of awareness. One that invites depth, presence, and emotion.

‘The Reintegration of the Ear’ reflects a counter-statement to the extraction mentality that dominates contemporary society. Can you elaborate on how you hope the piece fosters a shift in the listener’s relationship to nature, both in terms of what they hear and what they feel?

The statement is a bit complex, but I understand the spirit behind it. I do think it’s relevant to how I approach sound and listening. Music, for me, is inherently a collective, communal practice. Even when I’m alone in the field recording, I’m very aware of what I’m doing. I’m conscious that I’m taking something, capturing the sound of birds, for example, and with that comes a responsibility. I’m leaving a trace, even if it’s an invisible one.

That awareness matters. For too long, we’ve taken from the environment without asking or even thinking. Practicing a different kind of relationship, one that considers what we take and what we give or share in return, is essential. Even something as subtle as being present in nature with a spirit of exchange, rather than extraction, is part of that shift. It starts with a simple awareness, but it’s deeply needed in today’s world.

We’re constantly surrounded by examples of extraction. It’s the default mindset we’re conditioned into. So to ask, “Can we think differently?” becomes a radical and urgent question. That’s part of what The Reintegration of the Earis about. It’s not just about hearing. It’s about participating. About cultivating an active, reciprocal relationship with sound, with each other, with the environment.

And this carries over into collaboration too. Much of my work is ensemble-based, and The Reintegration of the Ear is no exception. When I collaborate with other musicians, it becomes an exercise in deep listening, mutual exchange, and co-creation. That experience, of building something together through attentive presence, feels like the opposite of extraction. It’s generous. It’s shared. And it’s essential.

The collaboration in ‘The Reintegration of the Ear’ involves a diverse ensemble of musicians, including Irene Kurka, John Also Bennett, and Oliver Coates. How does this dynamic influence the unfolding of the piece, especially when integrating such different sound sources , from synthesizers to live instruments to hydrophone recordings?

The ensemble is a huge part of the sound. I’m working with people whose sonic language I love, artists whose contributions are deeply meaningful and whose voices are distinct. This is the first time I’m collaborating with Oliver Coates, and I’ve been a fan of his work for years. His presence brings an entire world of detail. His cello playing, even the smallest gestures, becomes part of the piece’s atmosphere. It’s a deeply generous act to bring that kind of intimacy into a group context, and it makes the work feel alive in new ways.

John Also Bennett, who plays flute and synthesizer and who is also my partner, has a long personal and musical history with me. His way of playing has developed across time, and that shared evolution adds something subtle but powerful to the work. There’s an intuitive understanding between us that naturally informs the unfolding of the piece.

And then there’s Irene Kurka. Her voice and the way she delivers both text and melody drew me in through recordings. I didn’t know her personally, but I reached out simply because I loved the way she sounded. That’s really the core of how I collaborate, falling in love with a sound and following that instinct.

This will be the first time the four of us come together as a quartet. Until now, we’ve presented the piece as a trio. So Athens will be the debut of this full formation, and that adds another layer of excitement and intimacy to the performance.

Question from Carmen Villain:

In your work, how do you approach the relationship between listening and seeing?

For me, it’s through observing this relationship in nature. I like paying attention to how the sound of wind through leaves, for example, is embedded in the visual of a tree. Still, it’s tempting to try to focus on one or the other and sort of feel around for what happens. Sound travels instantly into feeling for me. I don’t sense any gap whatsoever. Seeing takes me to a feeling too, but in a reflective way, passing through thoughts first.

Subset Festival brings together a wide array of experimental artists. In a setting where sound, technology, and space are explored in depth, what do you hope audiences will take away from experiencing ‘The Reintegration of the Ear’ in this context, where the concept of “reconciliation” might resonate on a personal and collective level?

On a personal level, performing in Athens holds special meaning. My father is Greek, and though I haven’t performed much in Greece, returning to my roots and having my work exist in that landscape carries emotional weight. It feels like a kind of homecoming.

I’m especially excited about the context of the Subset Festival. It’s a beautifully curated program that brings together experimental artists in ways that feel both accessible and sensual. I hope that audiences, especially local ones, come away realizing that experimental sound doesn’t have to be abstract or difficult. There’s beauty, there’s feeling, and there’s a quiet invitation to listen differently.

The venue, the Athens Conservatory, is also ideal. Our set will be immersive. And while we’re using instruments often associated with classical traditions, such as cello, flute, and soprano voice, we’re blending them with environmental recordings, subtle textures, and a non-traditional approach to form. That juxtaposition can be disarming in the best way, opening people up to new ways of experiencing sound.

Ultimately, what I hope is that the music doesn’t just stay within the frame of the concert. That it lingers. That it sparks curiosity or reflection, maybe even reconnection. Whether it’s with the environment, with memory, or with each other. And especially in a city like Athens, where a new scene is emerging, anything that fosters deeper listening and a more vibrant community feels important. Music, at its best, can be a part of that cultural evolution: something more than just a performance, something shared.