“if you want to be happy, the easiest way is to not think about yourself”

Tension. Building. The forces at work are pulled taught, the feeling of potential flexes itself and finds relief in the ensuing moment almost effortlessly, the open palm closes. Final form is evasive because purpose is always readjusting itself, writhing, stretching to capacity but never beyond. The shapes we find ourselves in become mirrors for empathy when we understand the rubberband.

Simon and Jason, the New York City director duo that has chosen this monocher, are two parts to a whole and reflect the oscillating balance innate to its name. The body of work that they’ve created ranges from music videos featuring rising talent, to profile vignettes of big name talents like Offset and Solange, to campaigns for Reebok starring industry heavyweights like Pyer Moss and yet, regardless of conduit, rubberband. aims to embody the ineffable. Their dynamic works as pairs of hands extending outward from a two-way mirror, coalescing at unlikely junctures, tangling before realization, unafraid of the openness that subjectivity invites. Arranging gesture amongst shadow, sound as intent and light with colored emotion, Simon and Jason design narratives that utilize specificity to speak to a kind of universality that recognizes vulnerability as truth. We speak with the duo over FaceTime during quarantine from our rooms, scattered across the city, together but apart.

I know you both grew up either in NYC or within its vicinity and continued to remain in its orbit throughout your time spent at New York University where you met studying film at Tisch. New York, the city itself, is such an iconic, visual fixture that anchors the plots of so many movies and I’m wondering how it shaped your own lenses as you grew into your own as directors and as rubberband.?

S: I grew up outside of the city in New Jersey and I also lived in Italy for a bit when I was really young. My parents are professors, my mom is an art historian so I spent a lot of time in museums and there was a lot of discussion of art in the house. Living in Italy, immersed in the world of cathedrals and frescos, Michelangelo and Brunelleschi and Giotto, going to the museums, experiencing all of these things at an extremely young age I think really shaped my worldview. Those years informed what I wanted to do with my life— it was the thing that spoke to me most and I think film, beginning with making skate videos as a kid and all that kind of stuff, was just a natural progression from those formative experiences.

J: Yeah, neither of my parents were involved in art or film. My dad leased shopping centers and my mom was a menswear buyer for Ralph Lauren so I never had any classical or specific sort of art’s background. I got to carry the Thomas Walther internship at MoMa when I was in college. The internship was my first, direct experience in that kind of space and previously, I assumed that art was mainly about aesthetics, which of course it is, but working there I also got to see how important the historical doctrine of art was.

I really feel like growing up in the city was sort of the antithesis of film and inspiration in a way. The first jazz album I ever listened to, which is definitely a cliche, was Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue. I remember listening to Blue in Green on a computer when I was like 11 and thought that this is what New York sounded and felt like. I think that the synesthesia that occurred was a weirdly fundamental part of forming how and what I wanted to make. As Simon and I have grown together in our work, Simon is this very intellectual guy in terms of ideas and I think I am much more of a physical entity, which creates this sort of synergy. I think there’s this other part of film that a lot of people like to look over which is that film is a very physical process. You have to physically do it. I used an analogy a while ago, which Simon has heard a million times so he’ll probably laugh at me, but film is analogous to making a chair, making a bench or building a sculpture.

Yeah I just interviewed director Jonas Akerlund, and we were talking about the distinction between art and entertainment and how he sees film to ultimately lean more towards the latter than the former. On the other hand, with rubberband. in particular, you guys are specifically interested in the emotional propensity of filmmaking to evoke, mirror and create universal commentary on the human condition which to me, points to veering on the side of art. Can you guys walk me through your understanding of it all — emotionality, art, entertainment — and how you maintain a sense of integrity whilst in the mix?

S: They’re a lot of people who view those things as mutually exclusive, as if entertainment and art somehow can’t coexist and I don’t know if there’s a lot of benefit to that distinction or if it’s necessarily true. I think a lot of the art that shaped my life is both entertaining while also speaking to me on a level that transcends explanation. There’s something about the feeling that it evokes inside you and that becomes the magic of the thing. Jason and I joke about this a lot because I think there’s a real pitfall to over-intellectualizing while you’re making something. Whenever we go into a project we have a really strong conceptual understanding of what we’re trying to do but any attempt to define what you’re doing too specifically just seems inherently limiting. By defining something as entertainment or art, you’re automatically limiting the potential of what that thing can be. It’s not that we’re against labels, we just don’t think about it that much, we focus on making sure there’s something interesting about this idea and we both feel it.

J: I think that’s a really good point. I think whether you define it or not, everyone sort of has a philosophy about how they work and it might not be a thing that they’re even conscious of. In regards to intentionality with style, you should more so just act in the stream of how you feel and that’s what style is. I don’t think style’s about you trying to push a thing further than it’s supposed to be. You could talk to someone like Matthew Barney or Joe Swanberg about what film is to them and they would tell you totally different things, or they might tell you the same thing, but the way they get to those ends is totally different and that’s kind of the beauty of everything — that it’s totally subjective. There’s no universal truth in any of this. People are just trying to get at something that they feel and they’re acting in the course of action that they think is the most direct to get to that result. To think about why too much is sort of self-defeating because you’re immediately comparing. It’s a lot less about thinking and it’s way more about just doing something, just do it in a vacuum, do it in your room, do it wherever, whenever and see what happens.

S: Yeah our philosophy surrounding all of this stuff is sort of just be as open as possible and always foreground that idea that all we know is that we know nothing. When we make something — every single person who watches it, they’re having an entirely unique experience with that object. We realized that this idea of control or ownership of what you make in a certain way is like holding onto water, you’re just letting this thing go and you have to see how people receive it.

“Part of the fun is when someone comes to you with an experience of your work that is completely different because they bring themselves into it.”

We’re always wary of absolutes and people who have these really rigid philosophies and create these kinds of binary distinctions, something about it never really feels right.

J: I would rather be a hypocrite than a person that thinks they’ve had it right since the beginning. Everything that we say is subject to us changing our minds five minutes from now.

Yeah it creates space for growth and what you guys are saying about this kind of pervasive openness, truly letting go of expectation, authority and ownership in a way — does that feel radical to you? What feels radical in filmmaking?

J: To what Simon said earlier, to define it as radical seems besides the point almost to me. I don’t think anyone that does anything that’s really special sets out to do something special, they just do it. Now we make films, we fucking advertise for clothing companies at the end of the day and so we’re certainly not doing what Gandhi did, but I think that this sentiment of acting in accordance with what you think is correct and holding steady to it eventually leads to one of two things happening: either one, you prove yourself correct, or two, you prove yourself wrong and whilst in pursuit of that thing, you actually find a different angle to approach it in. People refuse to ever admit that they were wrong and it’s totally really prevalent in society right now. We’re 26 years old and we have so much left to know and to stand steadfastly by something that you essentially stab your flag in I think is insane. Anything that you learn at any point can change your outlook on everything so the idea of being radical, the idea of trying to do something new is I think a result, it’s not intent. You intend to do something that you think very specifically about, and you try, and then you either fail or succeed and you move on. And I think that keeping those goals very physical and logical ends up being a lot more interesting than trying to keep them like huge and grandiose.

S: In that question of asking about the idea of being radical, it presupposes an intention that to Jason’s point A) I don’t know that we necessarily think about, but I think also B) I think the thing that we’re ultimately chasing is pretty ephemeral. I think it’s about making something that just really embodies the ineffable in a way. It’s not necessarily this thing that can be articulated, it’s more about trying to create something that captures a set of feelings, or evokes those feelings in a way that feels sort of externalized. We all have this reservoir of feeling inside of us and I think a lot of those feelings can’t really be given form just through communication or interpersonal relationships, some of them can only be explored through making things. That feeling, that sort of harmony of looking at something we made knowing that it captures a feeling we were trying to excavate is how we define success artistically.

There’s also like a level of awareness inherent in all of that too. I mean, even just this notion of wanting to give form to the ineffable through visual transference reifies this need to be understood and to reflect understanding. It leads me to wonder what you think the relationship is between directing and curation? Both are ultimately tools and choices as means to this end.While curation has become a buzz word nowadays, it still enlists this idea of bringing footnotes, aka inner emotions, turmoil, things that we can’t place, to the fore.

J: My fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Maloney, who is like a very old woman, wise, silly and had these weird, Coke bottle glasses and she was the first person to say that cliche that you write what you know. Your experiences bleed out into all things. Curation as a conscious thing, it’s a function of how you get from A to B and it seems, again, something that’s sort of like antithetical to what we do.

S: If you’re going to make something, explicitly or implicitly in your decision making, it will reveal something about you because there is authorship in making. What we really take incredibly seriously exists on a craft level because the things that we make are the sum of their parts. No methodology is superior to another but we really enjoy bringing a certain level of intentionality practically speaking. It’s not necessarily like excellence because I think that’s impossible to quantify in a craft but we just really enjoy going in and nerding out about all the different details, which is what people seem to respond to but that’s just how we would do it anyway. It’s not as much of a conscious way of working as much as it is an organic process regardless that feels pretty natural.

J: Yeah I think curation is the idea of crafting an image and we’re not very interested in that. I think we’re more interested in seeing what inherently comes to us and what the image ends up being versus trying to shape the image in a direction that is ultimately not very natural for us to exist in. If we end up having an image that’s lame or whatever people interpret then that’s what we are, that’s what we have. To fight against that is silly because you can’t be anything other than who you are. Ultimately the sum of those things is like what we interpret as curation.

“It’s not about crafting a thing, it’s more about just putting the thing as it already exists, it out there.”

Yeah it’s an openness to vulnerability, to share, to be honest. What is your relationship to vulnerability in relation to masculinity? Not just in your work but in your personal life and identities as well.

J: Masculinity as it is defined is a societal term. We see James Bond and we think that’s what a man’s supposed to be — but the only reason why we think that is because someone told us that that’s what a man is supposed to be like, right? It’s not like there’s an inherent masculine quality.

S: What’s really beautiful too about the way we work is that most of the stuff that we do involves the making of it for and with someone else; and that collaborative nature is the most exciting aspect of what we do. But yeah sure the emotionality might be considered antithetical to prototypical “masculinity” During a very short window of time, we are able to form an incredibly intense connection with someone and that has a certain degree of a vulnerability built into it. We’re able to step into other people’s worlds and learn to exist in their universe. Entering into that space requires you have openness, empathy and compassion for who they are. It’s a lot of sensitivity, a lot of humility, a lot of leaving your own ego and their own preconceptions of you at the door. Collaborating internationally with such a wide number of people has yielded this beautiful result of mapping a three dimensional understanding of the world through what we do.

J: I also think vulnerability is ground zero, right? Like emotion, earnestness and trying to be honest are the only things that anyone can try to do with any of this stuff. Emotional vulnerability is kind of like the same thing as saying you’re telling the truth, right? Vulnerability is a universal language. Telling the truth is a universal language. Simon and I tend to think that people are a lot smarter than a lot of people give them credit for and I think bullshit is immediately detected. You know when something is lying to you. People are emotionally vulnerable about the things that are specific to them and the more that you can identify with someone’s specific emotions, weirdly enough, you end up speaking to a larger group of people. Specificity is the heart of universality. the more that you can communicate honestly on a very rudimentary level, the more universal you get. I think this kind of understanding is something that we like as part of our philosophy for the time being.

Right and I literally had those same thoughts in my notes: specificity as universality. But in regards to your process, knowing that you guys try to pre-visualize everything, is this where specificity comes in and are you only specific to ensure a certain result? I can imagine that things have a way of manifesting differently quite often.

J: We make plans so we can break from them. Plans are like shopping lists. You make a good plan, you get all the ingredients on the list, you know whatever meal it is that you’re going to make is going to be tasty, nutritious or whatever it is that you’re going for. But then you go to the store and you see something that’s in a season, it’s better, and you want to incorporate it because you’re acting in the moment and seeing something new.

S: Yeah I think it’s just as simple as preparation in your mind’s eye can only come so close to the living, breathing reality of making something. Whenever you’re on set there is this really heightened awareness that everyone has. We have this limited window of time to make something and that kind of situation breeds a certain energy where people are reacting to a very real set of circumstances that go beyond words on a page or images in a bank of references.

“It’s really all about being able to have a clear vision for what it can be but also being open-minded enough to completely let go of that when it’s unfolding before your eyes.”

It’s interesting that you mentioned the word authentic because it has become such a buzzword throughout agencies and industries alike. You’ve worked with big name talents like Offset, Solange and Pyer Moss for established companies like CR Fashionbook, Calvin Klein and Reebok who have clear visions and metrics for success. How do you approach these projects that are so ROI driven with honesty, openness and vulnerability being your ethos? Do they always work with or against each other?

S: I think a really important thing to know is that film inherently is contrived; especially if you’re talking about a big campaign like some of the ones you mentioned. For example we did a campaign with Moncler and you’re talking about over 100 people behind the camera, trucks backed up outside the studio. There’s no illusion that when you walk on set we’re going to somehow mold it to feel real. The way that I think about it is that everyone at all times is performing, consciously or unconsciously. I don’t think that there is necessarily this fight between the real you and the performative you. I think we’re all in some state of performing to try to engage with whatever the thing is that we’re in communication with. Just recording human behavior at the end of the day.

J: At one point a year or so ago, we kind of looked at each other and realized that while there’s a certain minimum level of talent threshold, beyond that it’s more so about who you are as a person. When we were younger we tried to talk shop with creative directors, artists and brands and ended up figuring out that they way more interested in things like what restaurants we really liked, or an album we thought was cool and it ended up being a lot more about identifying with people on a personal level than the technical aspects of making a film. People like Quentin Tarantino or John Waters are very specific personalities and they get very specific things from people and not necessarily for any craft reason. They are this person and rather than try to act against who they are, they try to act into it and that’s how they get all this interesting stuff that we are so captivated by as a society. It’s much more about who you are as a person than being talented.

“The talent lies in the response you get from the people around you to who you are.”

You guys are talking so much about relationships with people but obviously we have to focus on the one that is right here, the one that exists between you guys. To what extent do you guys see each other as mirrors for one another?

S: We often joke about the ideation process as creative arm wrestling because we both see the world differently. At a certain point we gave up trying to pull the other person into our world and started to embrace the weird intersection of these two distinct world-views and creative energies and realized that the thing that we’re making, neither of us can make individually. Oftentimes things that are seemingly at odds with each other aren’t allowed to co-exist or come together and we like challenging that. As Jason said, we’re best friends and a big part of it too just having a lot of fun. We’ve learned to trust and respect the weird collaborative energy.

J: You inevitably become a mirror for each other. Simon’s qualities and my qualities become reflected in each other. There’s a real serious emotional support system that almost supersedes everything else. It’s caring for this person as a human being and then also caring about them in a creative aspect. Simon has my back, Simon would jump in front of a train for me and I would jump in front of a train for him and it goes beyond being creatively interested in something. It goes to a sense of love and that’s a unique part about what we have for each other. I think that that makes the work specific, maybe not better, but it makes it specific. I’m very proud of that specificity in our work.

That’s beautiful. To what extent you guys think empathy is a choice and how do you choose it every day?

S: One story I think a lot about involves the writer of Jurassic Park and his agent who came to visit him when he was terminally ill. The parting words of the writer were, if you want to be happy, the easiest way is to not think about yourself. I don’t know how you recalibrate your way of being, that’s a relatively hard thing to do, particularly as you get older. Solipsism, prioritizing oneself over others is a sure way to fall into a lot of really unfruitful and unhealthy feelings like envy, or lack of worth that in turn lead to difficulty with self-love. If you realize that the internal self is a very fixed thing that isn’t necessarily susceptible to all of the energy outside of you, you can create a sort of force field for yourself. I think anything that you see or feel negatively about in another person is really just a reflection of something that you see in yourself that you don’t like. I’m not saying I’m an expert on this or anything like that but I think it’s important to remember is that life’s hard, we’re all fragile, we’re all struggling and we have to use these truths as a bridge between people.

J: My simple addition to this is that I think empathy is a function of age. My dad, who I love a lot, is a very selfish person but to be fair to him and to everybody, inevitably we all only have our own eyes to see the world through, making empathy a choice. He acts in his own self-interest by caring about others. His empathy is a function of his selfishness, in a strange way. I don’t think altruism exists but as you get older, you see more things. I really hope that I am three times as empathetic as I am now when I’m 75. As a young person, it’s really easy to see our whole lives in front of us and to be very aware of that and thus care a lot about ourselves and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. We are the only things any of us really have physically. But as Simon said on your deathbed, you can’t stack your money and fall asleep on it, you can’t take it with you. Inevitably the only thing you have is your relationships with people. It’s not the number in your bank account, it’s the number of people at your funeral. Hopefully it grows with age, hopefully with more intelligence and the more things you know, the more you end up realizing that caring about other people is the same thing as caring about yourself.

Credits

www.rubber.band.com

www.instagram.com/jasonfilmore

www.instagram.com/simondavisfilms

www.instagram.com/_rubberband

https://vimeo.com/422144005?embedded=true&source=vimeo_logo&owner=45274582

rubberband. is a directing duo comprised of Jason Filmore Sondock + Simon Davis, operating out of New York City. They met in NYU Tisch’s Kanbar Institute of Film and TV in 2011 and have been directing to together under the moniker since the end of 2015.

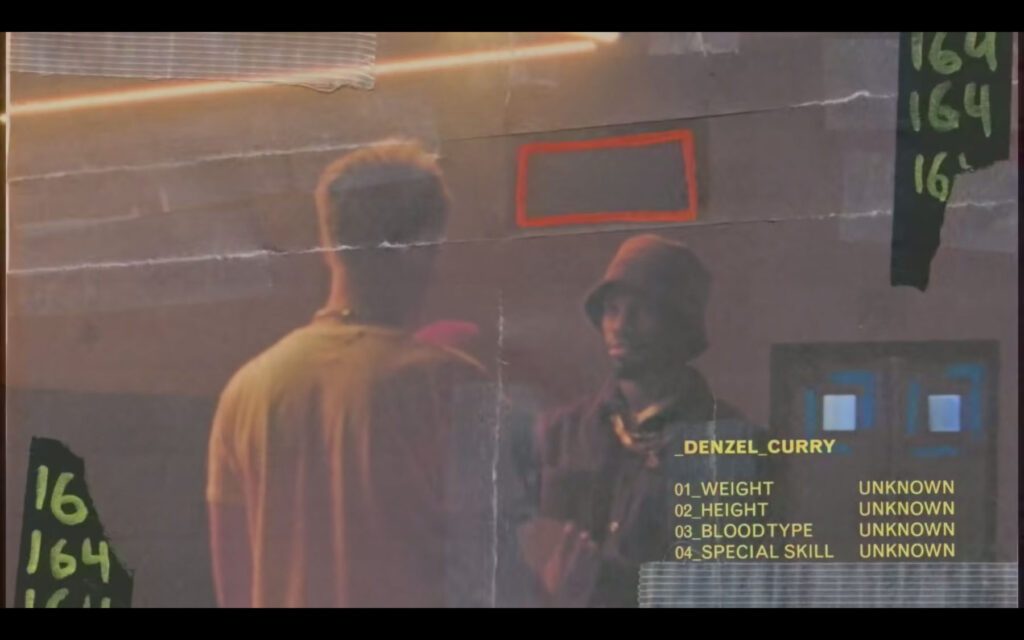

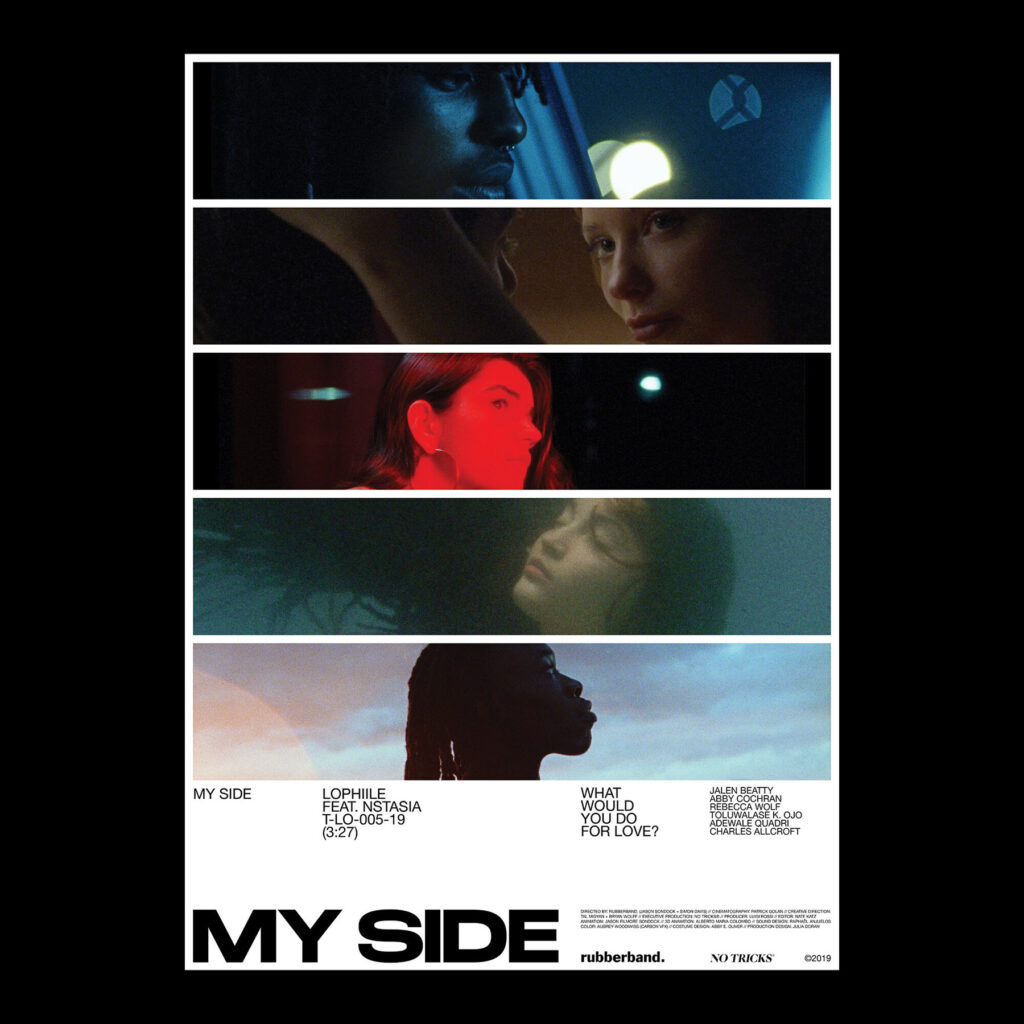

Their commercial work includes work for clientele such as Under Armour, Calvin Klein, Fender, Moncler, LIFEWTR, Burberry, Away, Raf Simons, and Alexander Wang. While their music work has included artists LCD Soundsystem, glass animals, Goldlink, ZHU, Alunageorge, and Bryson Tiller.

Their commitment to soulful, earnest filmmaking and forward thinking aesthetic design has garnered them attention from major publications (Rolling Stone, Huff Post, Buzzfeed, Hero Magazine, Last Mag, King Kong, Hypebeast, Complex, The Fader, Dazed, and I-D Mag) and garnered many festival selections (SXSW, LAFF, Cleveland, Sur e’Art Montreal, SUFF, and many others) and awards.