“It’s just that algorithm of life, greatness takes time”

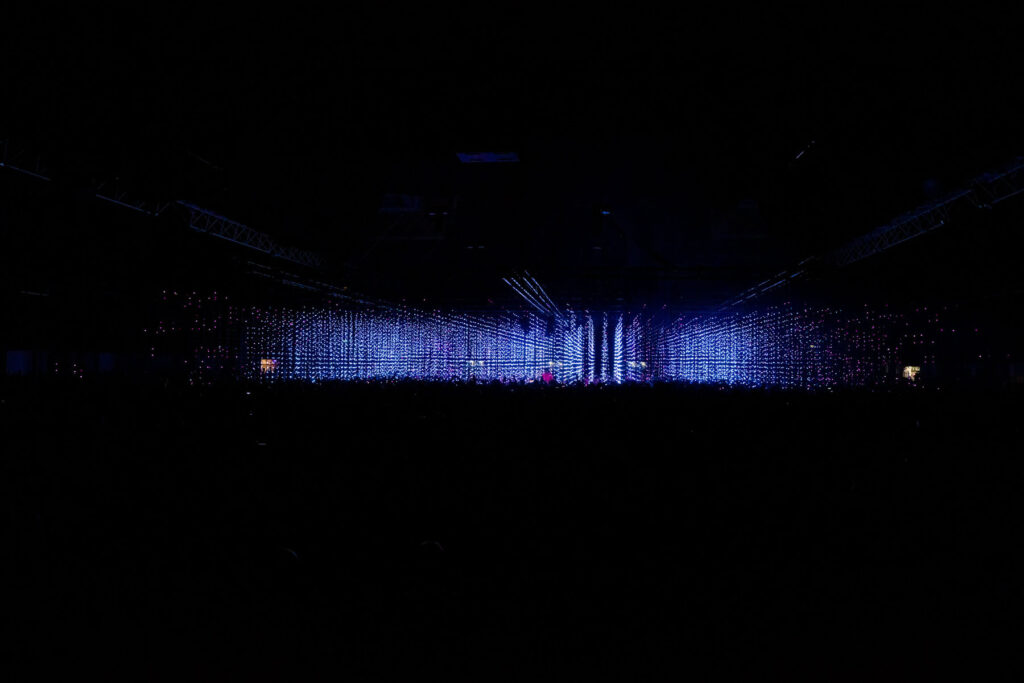

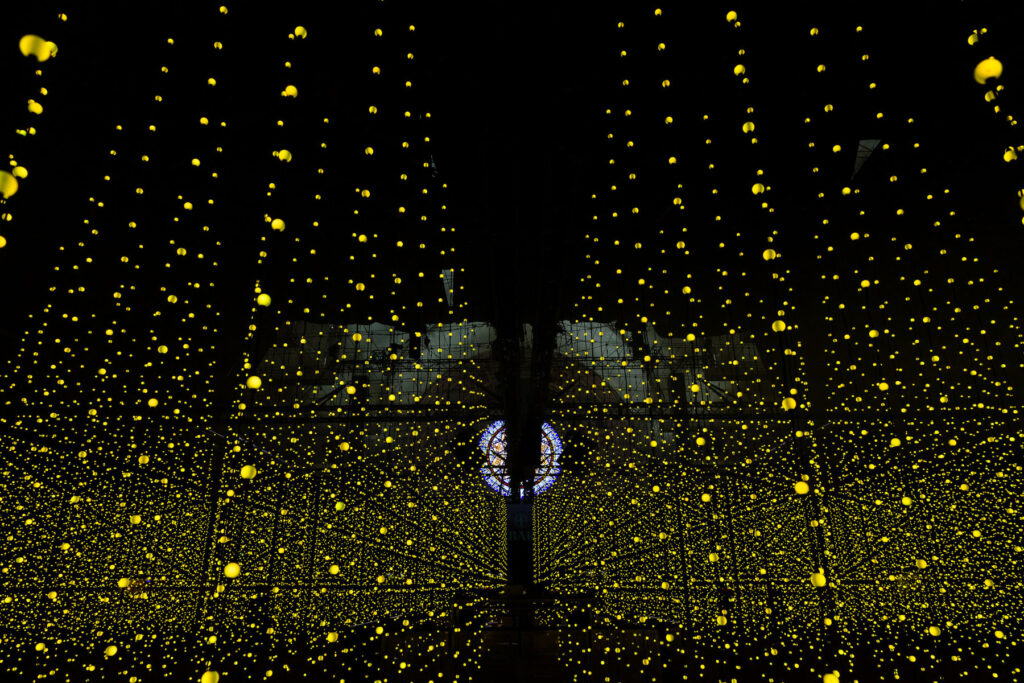

Nostalgia knocks on D’Anthony Carlos’ front door with branlike knuckles. Memories materialize into wispy shapes and heavy eyelids flutter conjuring the fading, fluorescent pink lights reminiscent of discos past. Blink twice and the heavy strobes from sold-out shows and basement parties alike flash as he drifts in and out of jet-lag induced sleep still hours before dawn. The DMV (meaning places accessible in Washington DC, Maryland and Virginia by the metro) native is better known as the Grammy-nominated rapper, Goldlink. He’s home for a few days between touring with Tyler, The Creator on his US Igor tour and gearing up for his personal biggest tour to date of the European continent to promote the release of his newest album Diaspora, and he’s trying to recalibrate. Having become a household name in the hip hop industry having birthed sans uterus a genre of his own called “future bounce,” Goldlink splices thumping house, eyes-wide-open club and silky R&B, to create an auditory landscape solid enough for his hometown to call a foundation. An identity turned dance floor.

When Goldlink’s home, he doesn’t leave the house. Success becomes clear when he returns to standing in front of his bathroom mirror, where his reflection remembers and exhales on its own. If the shower’s running the steam gathers to spell out retribution. He’s come to understand the rest of the world by first understanding his city and considers comparison to be a fruitfully empathetic lens. The DMV’s rich culture is steeped in its “Chocolate City” roots, wrought by fables of the American Dream, gentrification and dancing feet that echo the drum snare. He strives to preserve the city’s original vibrance by coloring sound with feeling and you can bet that it evinces in shades of brown. Having grown up as a product of divorced parents in the District’s darkest years as the grim reaper plucked lives with outstretched hands and eyes closed, Goldlink turned to music as his forever sensei. Through it he’s been able to find the answers to the lingering questions of ‘why me?’ as his path is hand laced with perseverance. This unwavering dedication to his community has in turn grown to understanding that sometimes to love home, means having to leave it. Growth is not only an open wingspan, it is the flight itself, a reinvention without reincarnation.

Whether it’s from reading previous interviews or dissecting the verbal homages that live between the bars of your lyrics, it’s no surprise that home and the DMV, not only mean a lot to you but it’s a defining factor of your identity.

Home for me is the space that you’re most comfortable being in. A place that you can reset yourself you know. That’s really it, I’ve been a lot of places that feel like home but there’s no place like home really.

When you’re kind of talking about resetting yourself I think it’s this idea of like holding up the mirror per se. I don’t know if it’s this way for you, but for me and being from Hawaii, it’s going to my grandma’s house or something like that. What does resetting yourself look like?

Yeah it’s chopping it up with the homies, seeing my son, seeing my family, resetting in that. It is the mirror aspect you were talking about and being able to look at and see yourself clearly in that mirror. It also allows you to see all the things that you’ve been able to accomplish while you were away and it’s the perfect time to do that.

Right and I feel like it’s also this level of honesty that you’re forced to face and it causes you to question what your personal definitions of fulfillment and success are. For you, you’re an artist, a musician and pioneer per se but you’re also a father, a son, a friend. Have your definitions of success and fulfillment changed at all?

It hasn’t changed much. It’s changed a few times throughout the course of my career but it’s kind of stayed the same recently. I think it’s as simple as focusing on something, accomplishing that task and that’s generally what succeeding means to me. Success can be anything really, it doesn’t have a linear definition as in like, oh this is what it is. I feel like I’ve just set certain goals for myself, accomplished them and then reset new goals and then I try to accomplish those things next.

Right and it exists in tandem with a level of perseverance. In regards to your music you’re always striving to have people understand how you grew up, your home, things like that but where does this need to be understood come from?

Being understood is a basic human need because it’s what we need to be supported. I also know that there’s a balance to it. People won’t understand everything, let alone understand it right away so I never really look for the acceptance of understanding immediately depending on what it is that I want to do. When I released Diaspora, I understood that it would come with delayed gratification. I ask myself if what I’m doing serves a purpose immediately and then if it will continue to serve that purpose in time.

What do you what do you mean by delayed gratification?

I am much a delayed gratification person because I understand where music is going, I understand the trajectory of things and I make it a point to do a lot of research to remain ahead of my time. Sometimes you need to be ahead of your time to serve a purpose in the landscape of today. We need those unsung heroes and I try to be that as much as I can.

And with Diaspora too I feel like you know obviously At What Cost from 2017 was so much about home, life in the DMV, creating that sound and then with Diaspora it seemed like you were extending outwards. Was it more so about just taking the next step in your career?

Yeah, it felt like the next step. It was like I tried to find myself locally and then was able to travel internationally to understand myself and my home even better.

Yeah there’s something to be said about leaving home and what it does to your own understanding of yourself.

I mean I still haven’t left but I’m okay with leaving because you have to grow as a person. I don’t feel like people should stay somewhere if they feel like they can grow somewhere else but you just stay where you’re needed. I’m never going to leave home entirely and I’m not confined to the definition of what leaving is, there’s multiple definitions of what leaving can mean. If you really love your home, you have to leave it to make it better. If I left and go around the world and compare my home to things that are happening in other cultures to understand and get a better read of why my home works the way it does. You know in order for you to change something entirely, you have to understand it from an external point of view.

Right. What does growth mean to you and is it always synonymous with change?

Yes. Like in order for me to grow I have to change so I think change and growth are like the same thing, not always but they should be.

How are they different?

Growth and change? Well, in order to grow you have to change. In order to change, it doesn’t mean you have to grow. It’s not like backwards compatibility, it’s not like it works only one way.

Yeah but it’s interesting in conjunction thinking about this idea in tandem with the concept of diaspora and the array of experiences that both differ from and are similar to our own. What does diaspora mean to you?

To me now, it really just means that everybody and every community is experiencing the same social economic problems and are dealing with it in the same way but they’re just different things. That’s really what diaspora means and we’re very much connected. You might do a Harlem Shake but in Hawaii you call it something completely different thing and in DC, we’ve got our own version too but we can understand each other and empathize through our own lenses.

You’ve mentioned having to deal with survivor’s guilt and the inherent inequalities of the American Dream and now that you’re in the spotlight it must feel like it’s been magnified. I think it doesn’t really necessarily go away, maybe it changes but I think it sticks with you.

Yeah it just kind of changes. Instead of being weird about it and feeling guilty, that guilt grew into me doing something about it, whatever that may be. It’s asking yourself, “that’s how you feel, now what do you want to do about it?” My answer was that, I’m going out and trying to make it fair for kids like me to be able to find a place to make it feel like they’re a part of something.

“I want to create the necessary stepping stones to making sure that that guilt continues to transform into something positive really.”

This issue is obviously called the reinvention issue and I think it’s interesting to think about reinvention in relation to sacrifice.

Ultimately it just depends on what you’re trying to accomplish in everything because everything is some sort of sacrifice and we all make sacrifices. I sacrifice my time, often my social life, to make sure that I accomplish my goals. I don’t feel any guilt anymore, I felt it at the time, just because I felt like “Why me?” I found all the answers to those questions. So it’s like I don’t feel that anymore and it doesn’t make sense to feel that way anymore actually. If you want to succeed, you decide to make the necessary sacrifices to get to that goal and you keep working through that goal indefinitely, and when you succeed where is the guilt? What is the guilt?

Right but it’s also perhaps also having to feel guilty for your success sometimes right?

Right, it’s just knowing that I’ve done everything I’m supposed to do to succeed. I knew what I wanted. I went to go get it by any means necessary and I worked really hard. I don’t smoke. I don’t drink, I’m not fucking, I’m just working and trying to be great. But what happens? You succeed at writing poems.

I felt guilty because it was so surreal, I’m going back to the community, writing the song, but why me? Why me? I have to tell myself it’s because you fucking tried and you cared. You did everything right. So you just succeeded.

Yeah. And I know you also talked about this whole idea of taking the slow road versus the fast road.

“Reinvention takes time but in a world of instant gratification we don’t give ourselves the time to process things.”

A lot of great people take the slow road. It’s just that algorithm of life, greatness takes time. Nothing and I mean nothing in the world comes fast and works forever. I don’t care what, who, and how you are, it’s never going to work. Things need to balance and things need a base. When you go too fast, you’ll miss it all. You’ll miss the hard part of things. You’ll miss the important thing that create sustainability. That’s why you can’t just be the greatest pianist overnight. You don’t know what it feels like to not be great. You don’t know what it feels like to lose. You don’t know what it feels like. Or, Steve Jobs is a perfect example of that, people like Jay-Z and Kanye West are good examples of people who take their time, every time they did something it felt like it was the first time but then when you look up it’s been 20, 30, 40 years, they take their time to learn something new. To continue to grow is a hard thing to do. There are certain things you can’t cheat, the universe you can’t cheat. If you think of anything that’s worked immediately, it never works forever, ever. It’s like a rule of thumb. I just always make sure that I’ll take the right road.

I think the misconception about me is that I could have blown up a really long time ago but I didn’t because that’s not what I wanted to do. It’s not that I can’t get on a track with Beyonce — granted that’s a hard thing to do. But it’s just like how am I going to enjoy being on Beyonce’s song if I’m one or two tapes in? That’s not smart. Beyonce has been making it for 25 years and that’s because she’s doing something right consistently and it still feels like she hasn’t dropped the biggest album of her career because she continues to grow, it’s amazing to see. It only feels like she can only get better. So that’s why a lot of the greatest people told me to take your time, so I take my time.

Yeah. And I’m wondering do we go through multiple reinventions or just one turn of the tide?

You go through multiple reinventions throughout your career, you can reinvent yourself as many times you want as long as you decide to grow. You’re not going to be the same person as you were when you’re 20, you’re going to be different when you’re 25, 32, you should decide when to be different, to reinvent. It’s nothing changing. It’s just adapting.

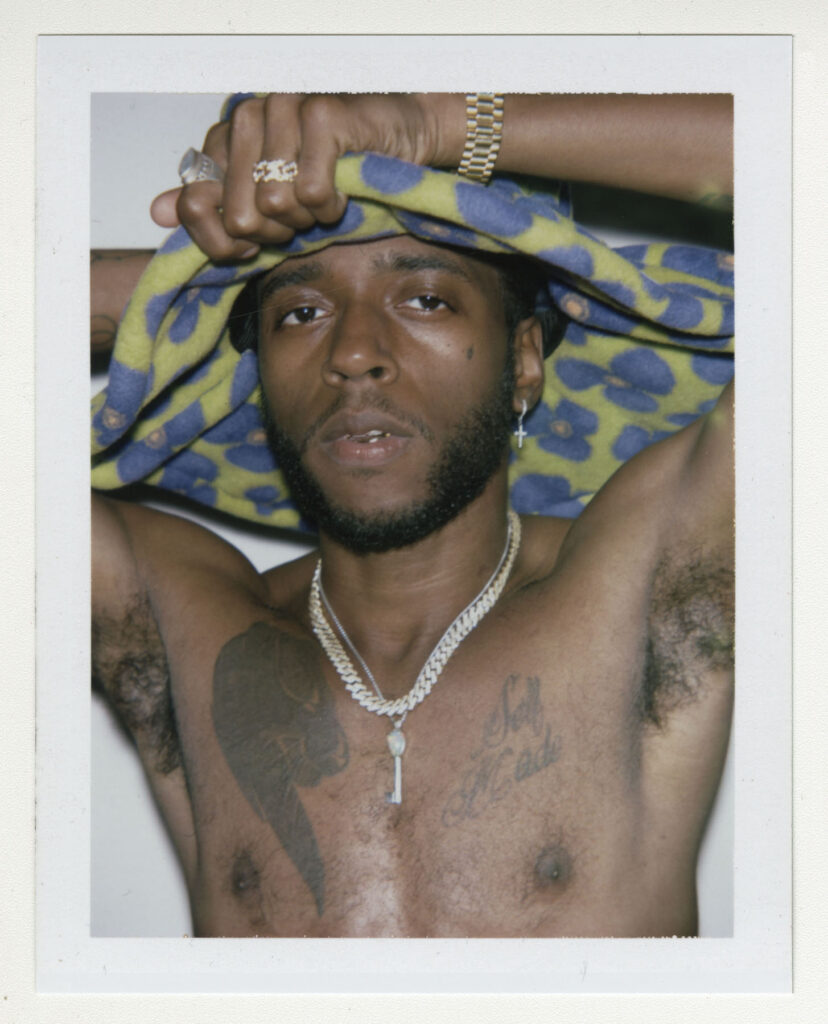

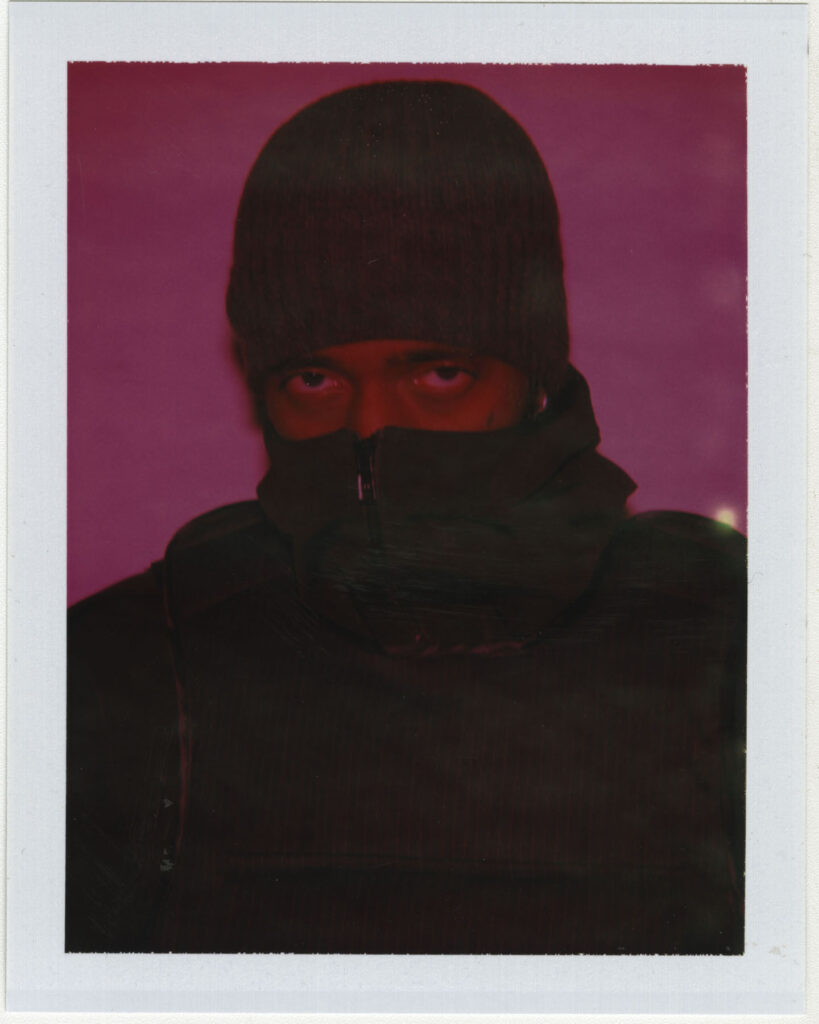

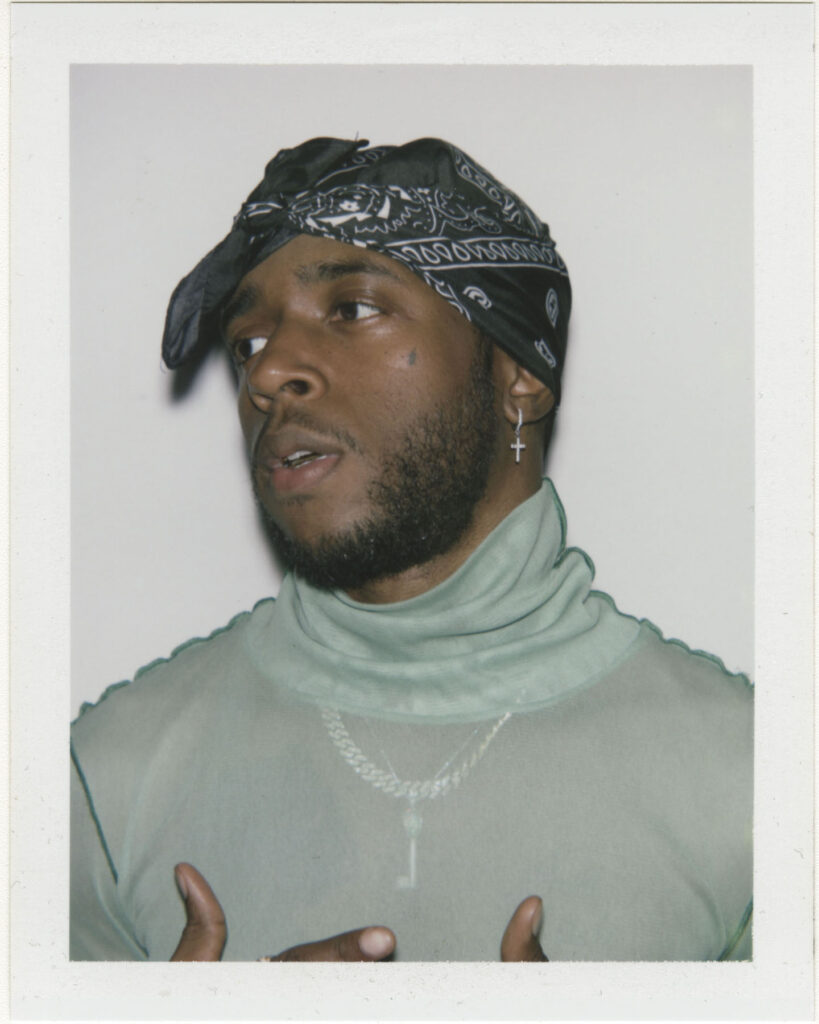

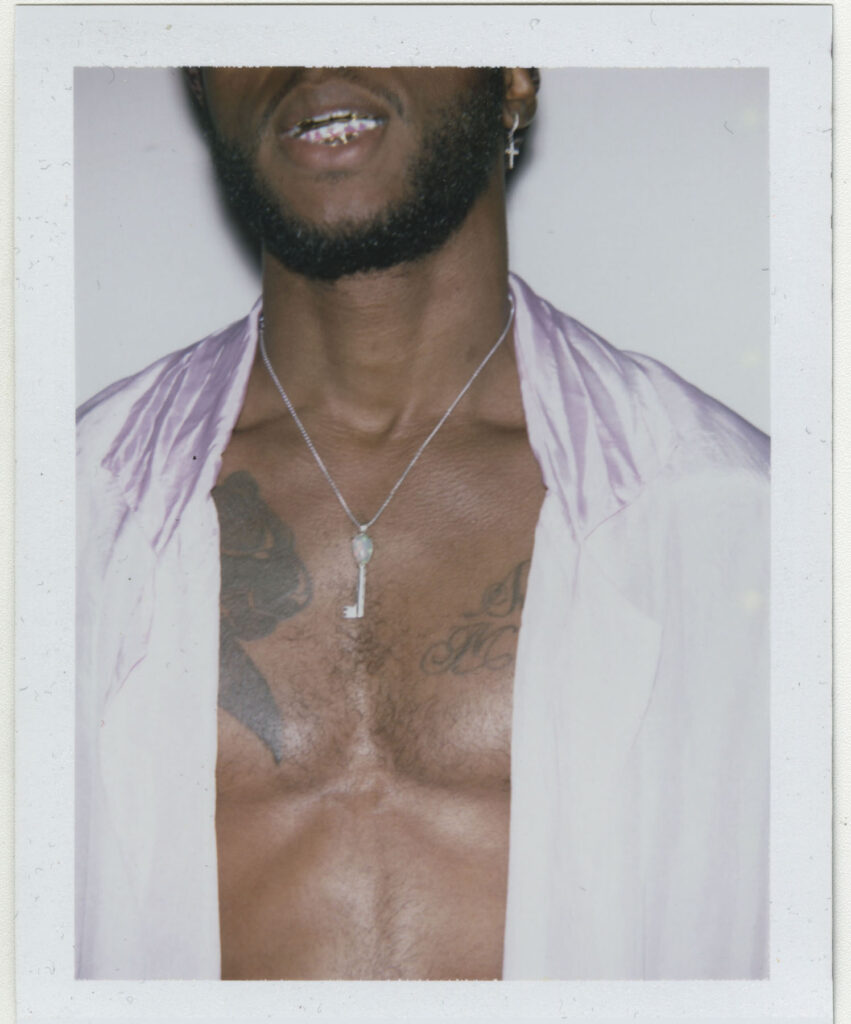

Team

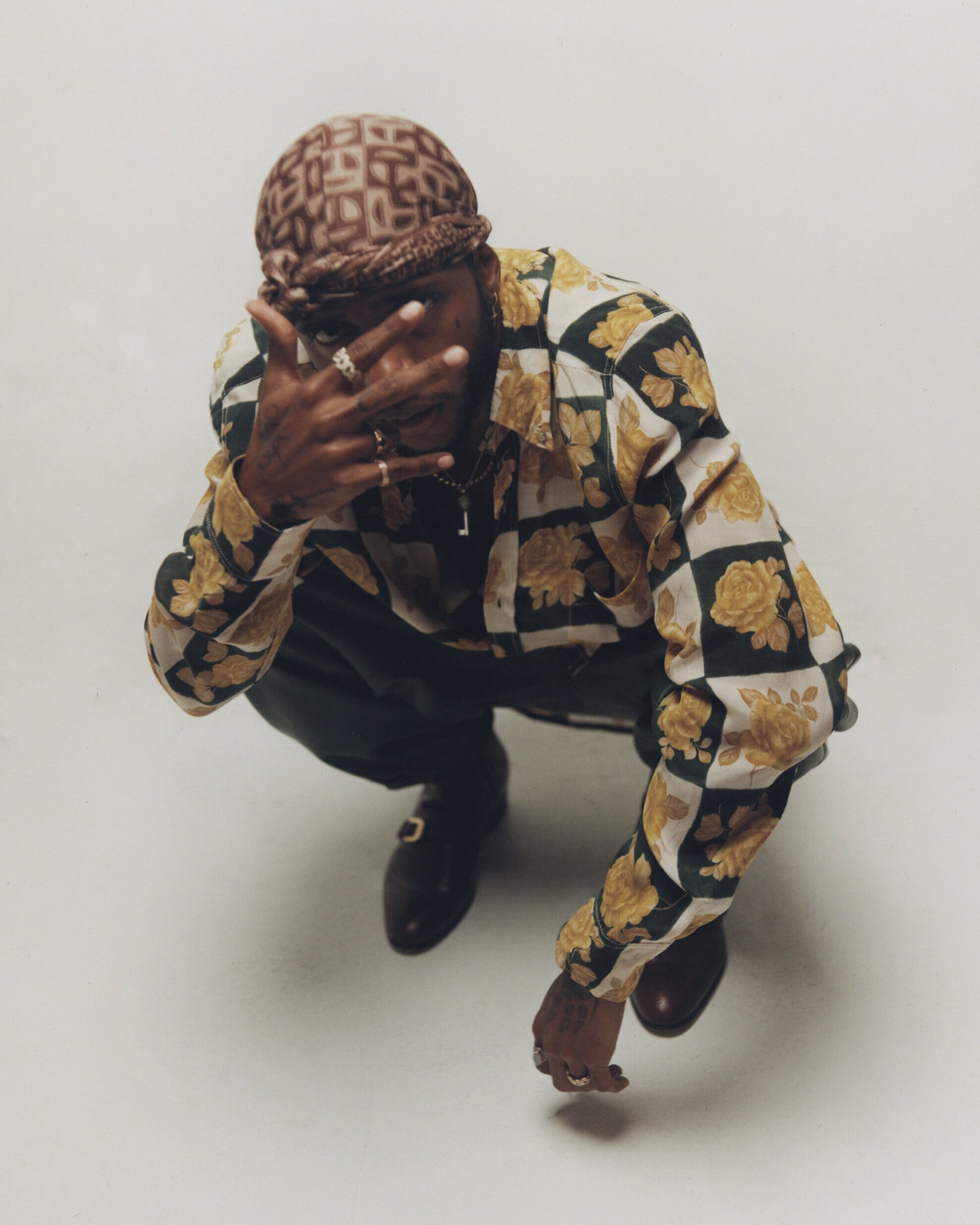

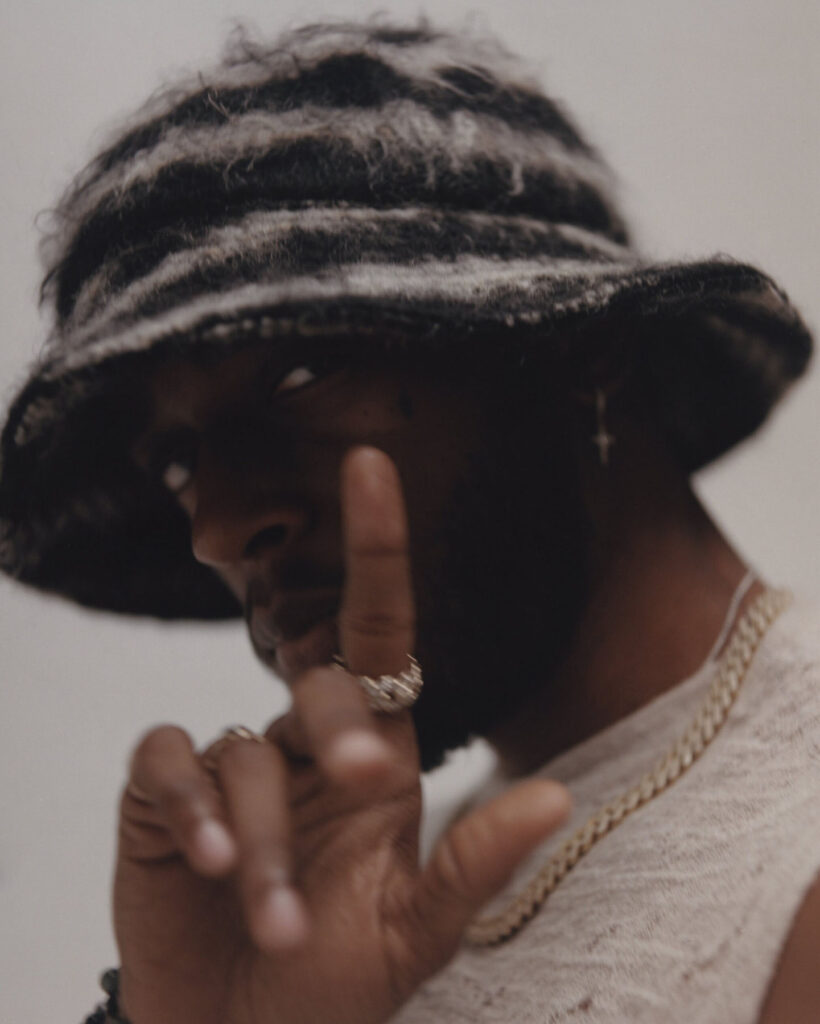

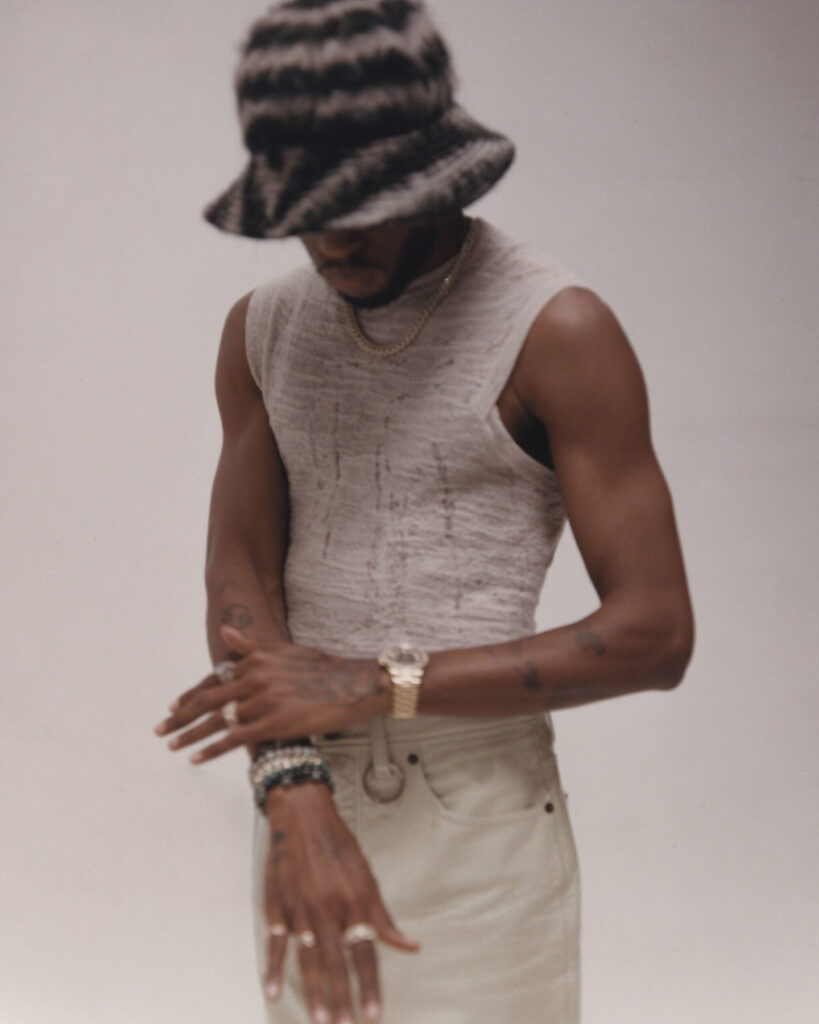

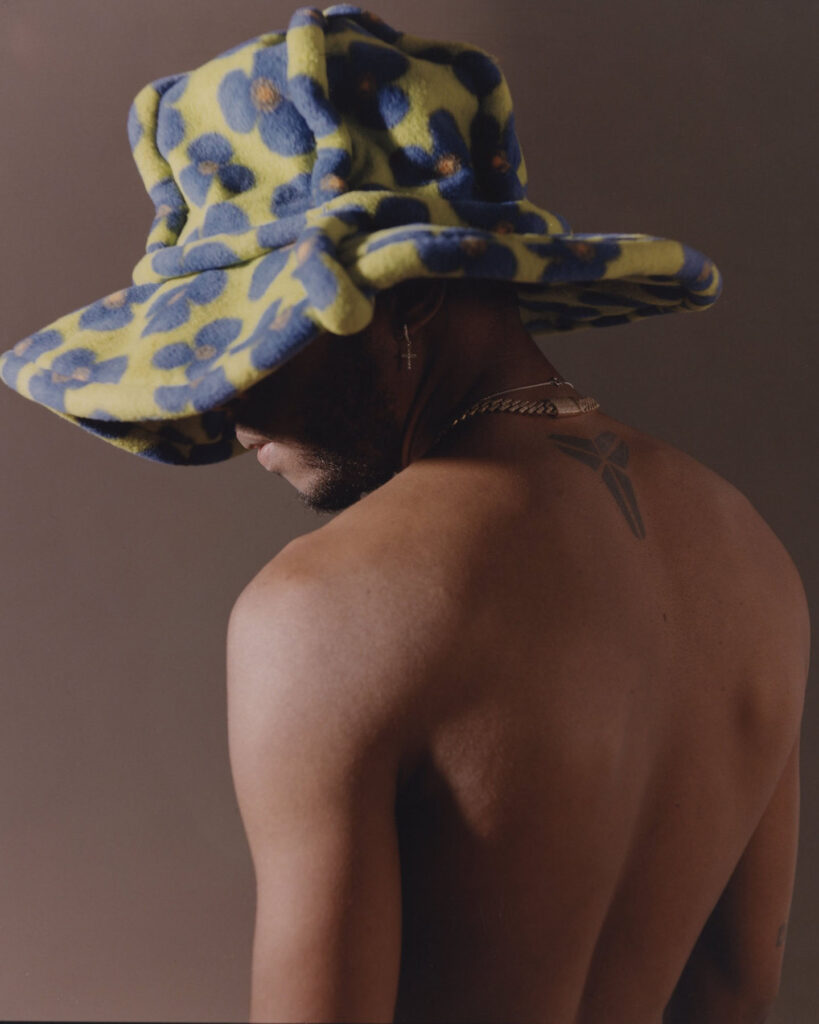

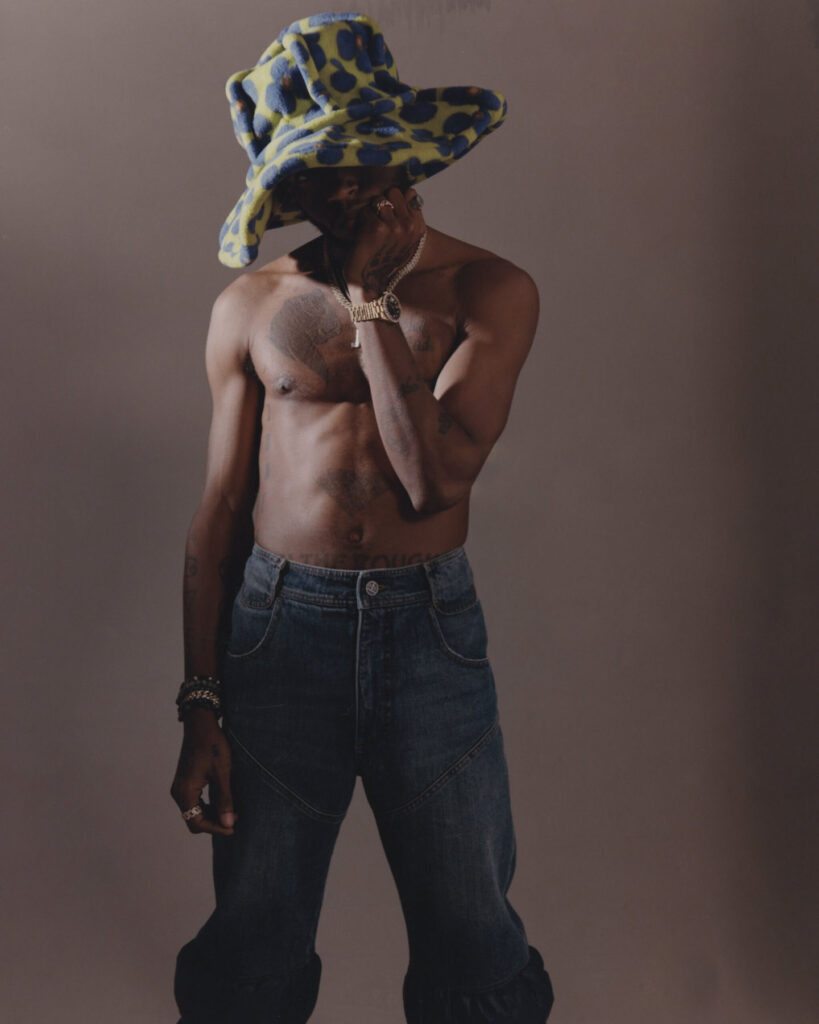

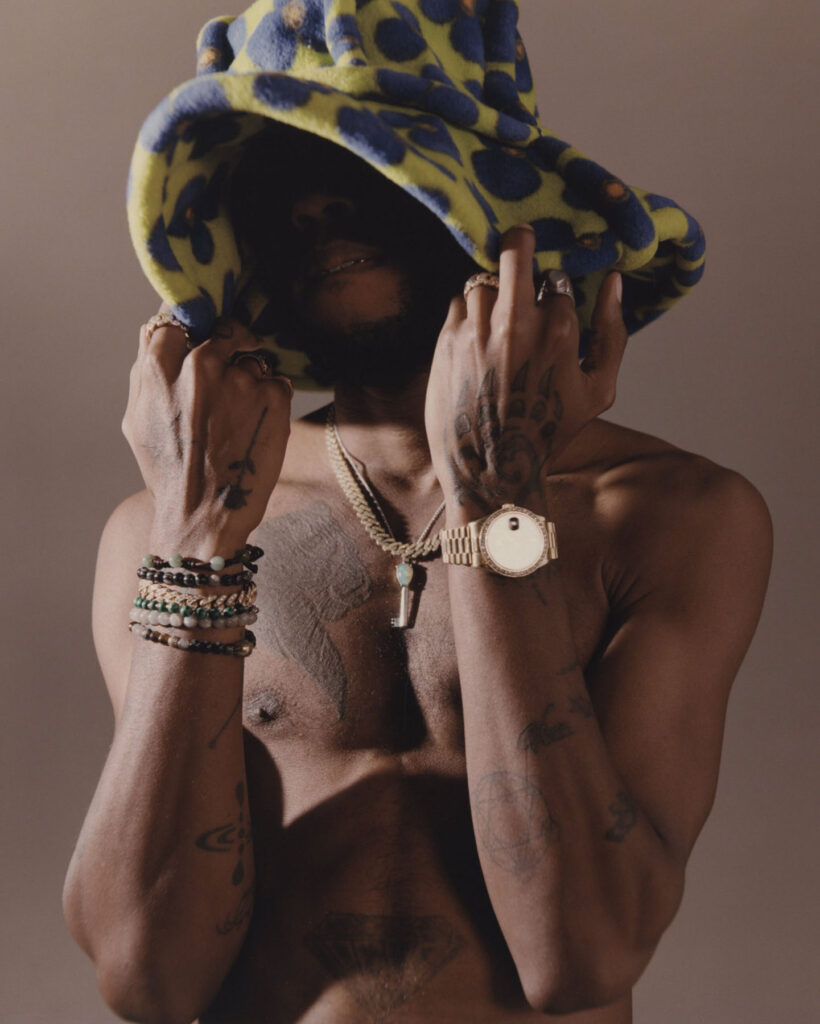

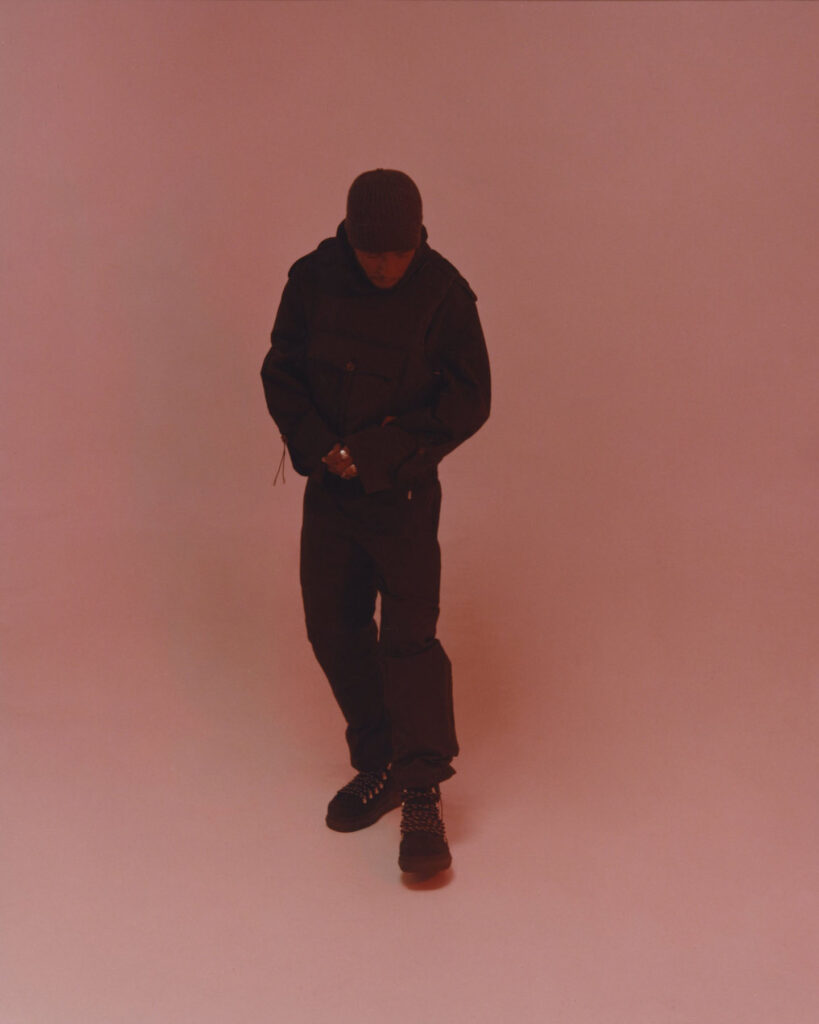

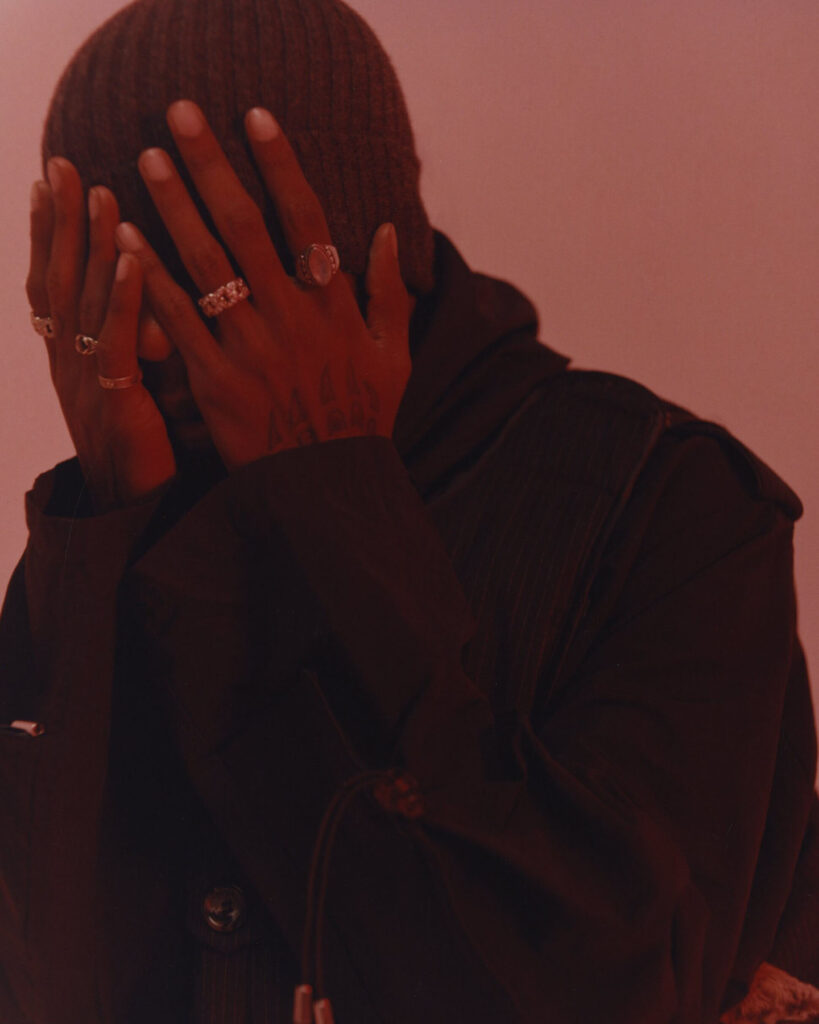

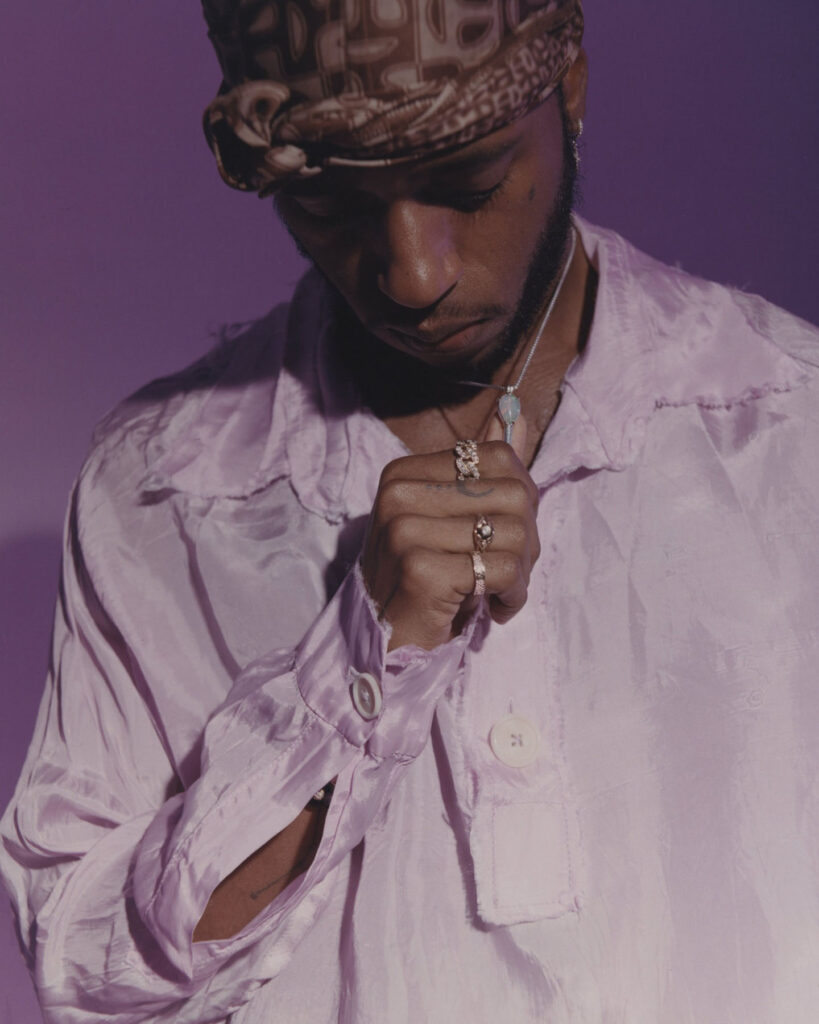

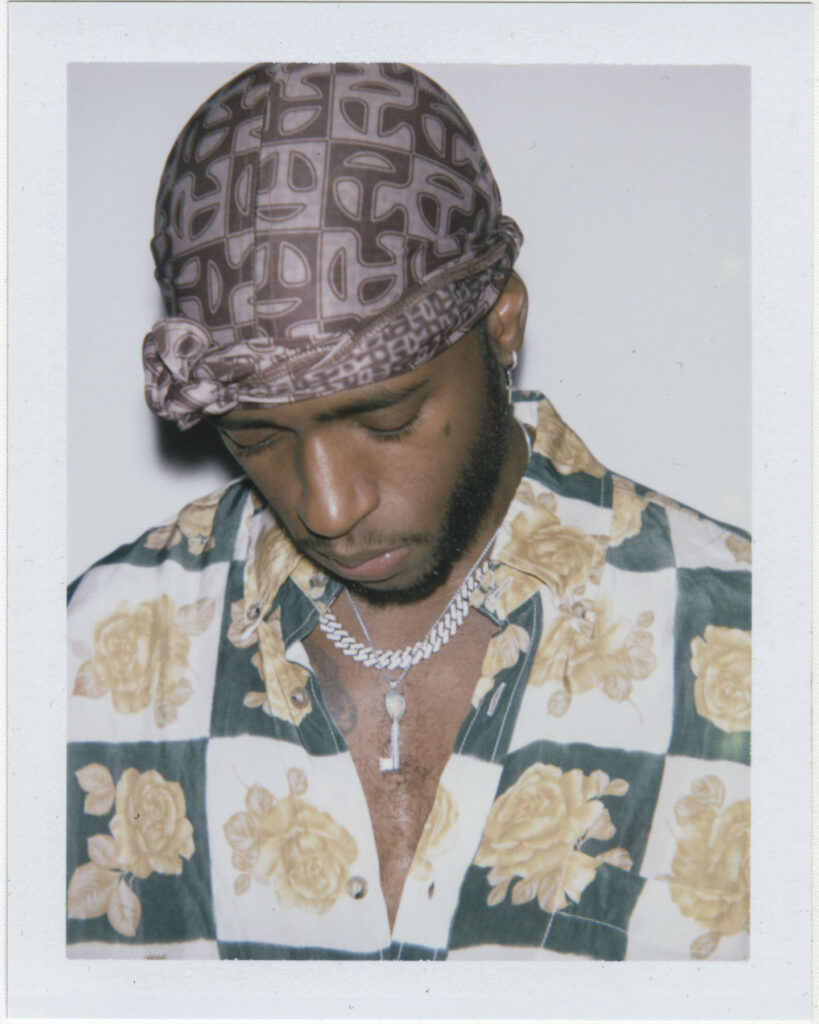

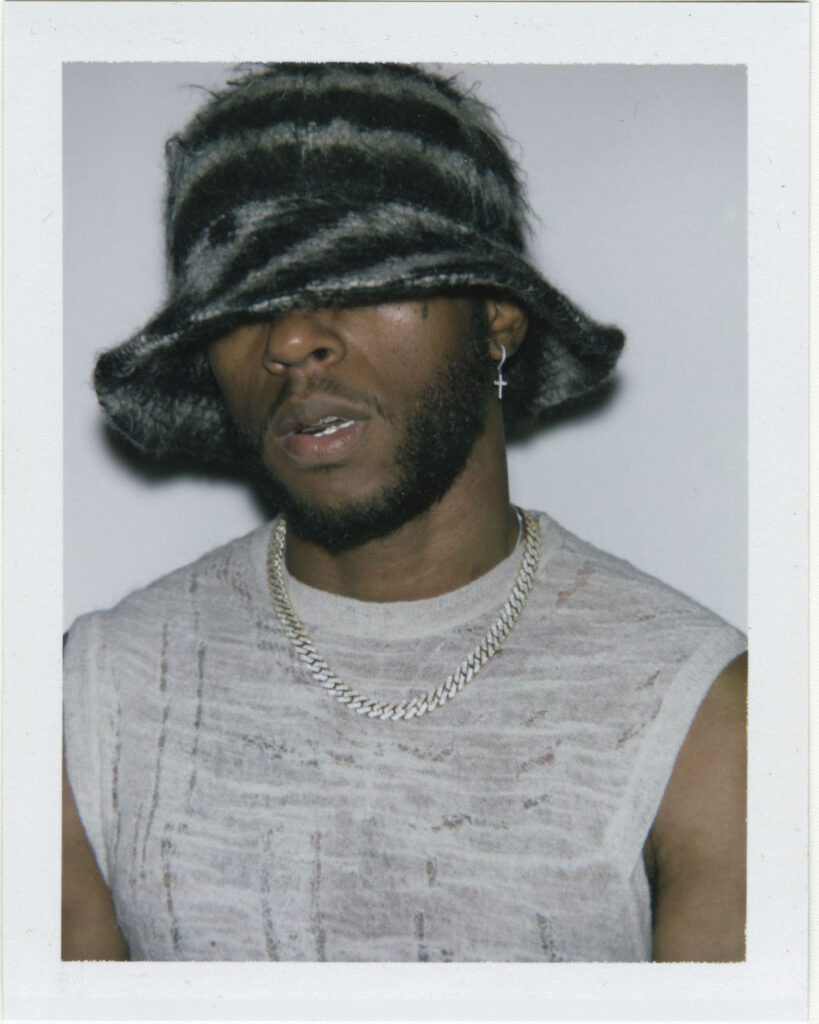

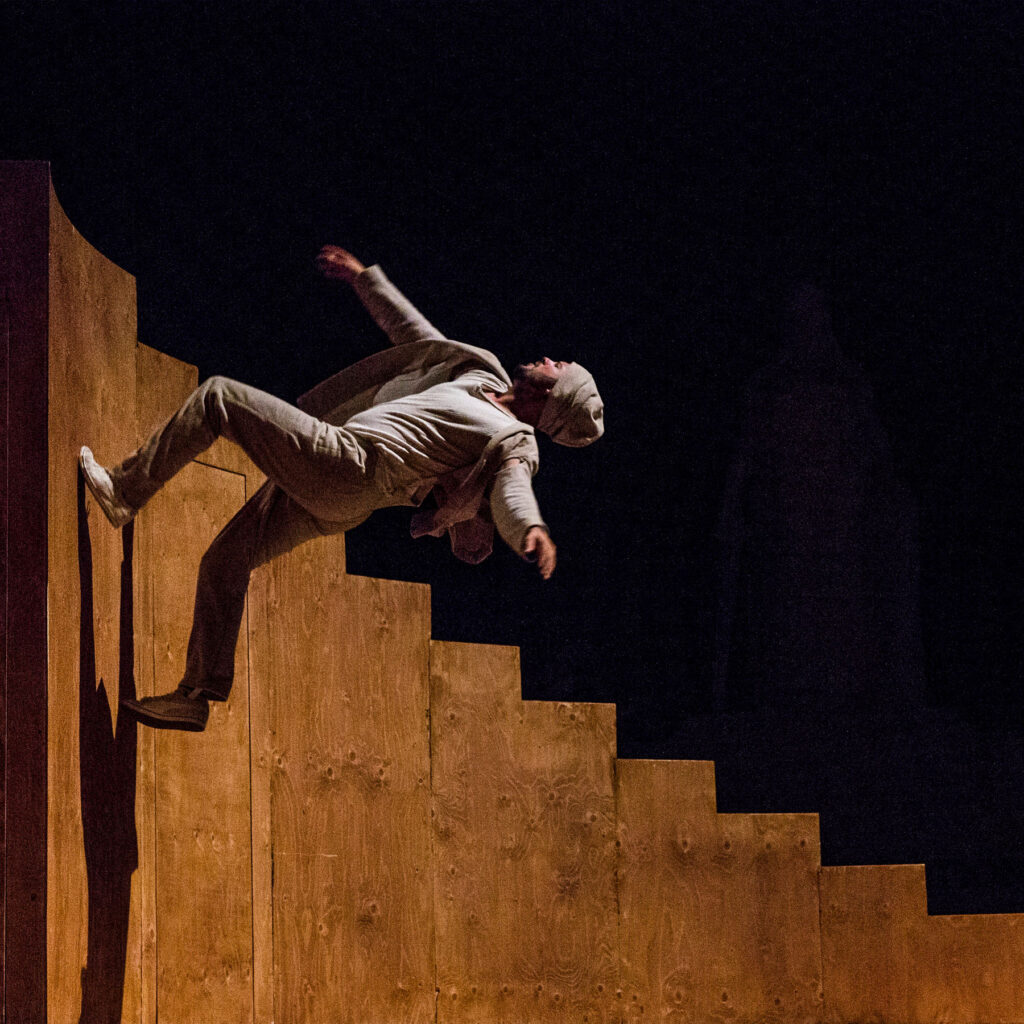

Photography · BRENT CHUA

Creative Direction · NIMA HABIBZADEH and JADE REMOVILLE

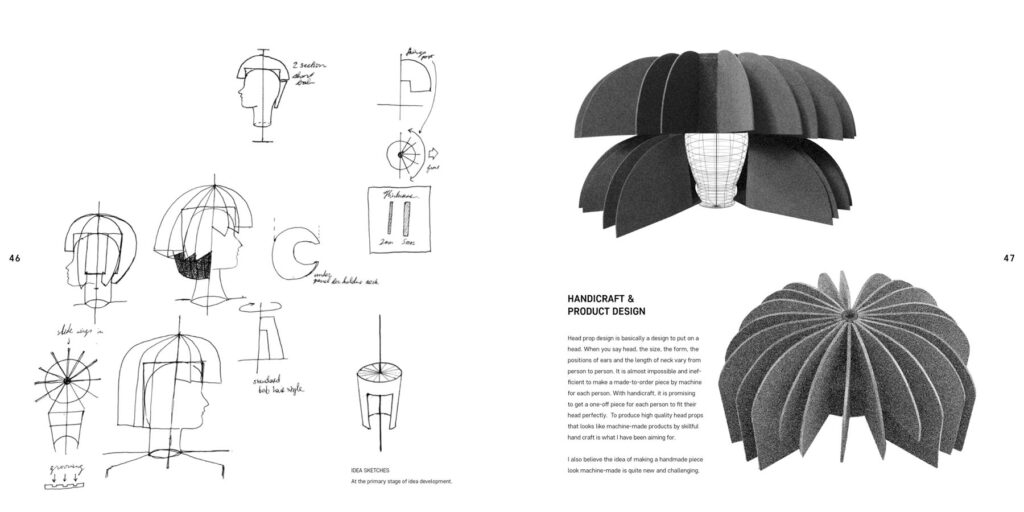

Fashion · LUCAS CROWLEY

Grooming · MARCO CASTRO

Interview · LINDSEY OKUBO

Designers

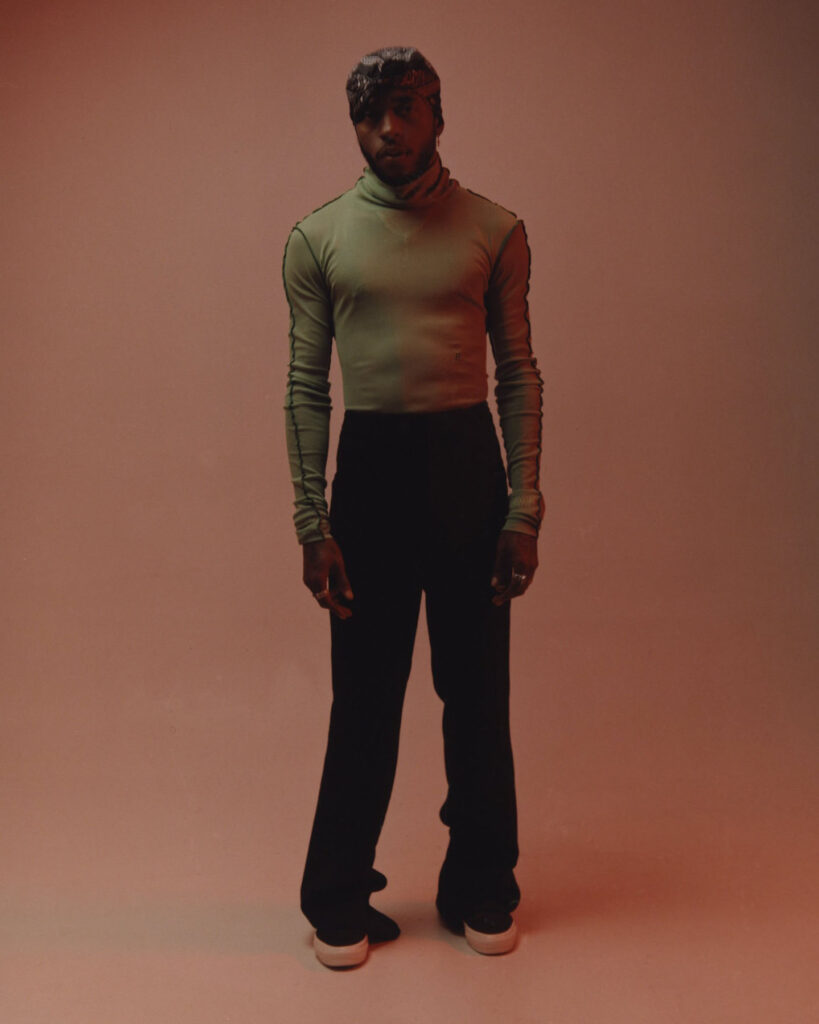

- GoldLink wears custom pieces made for his current tour through- out.

- Full Look ANN DEMEULEMEESTER