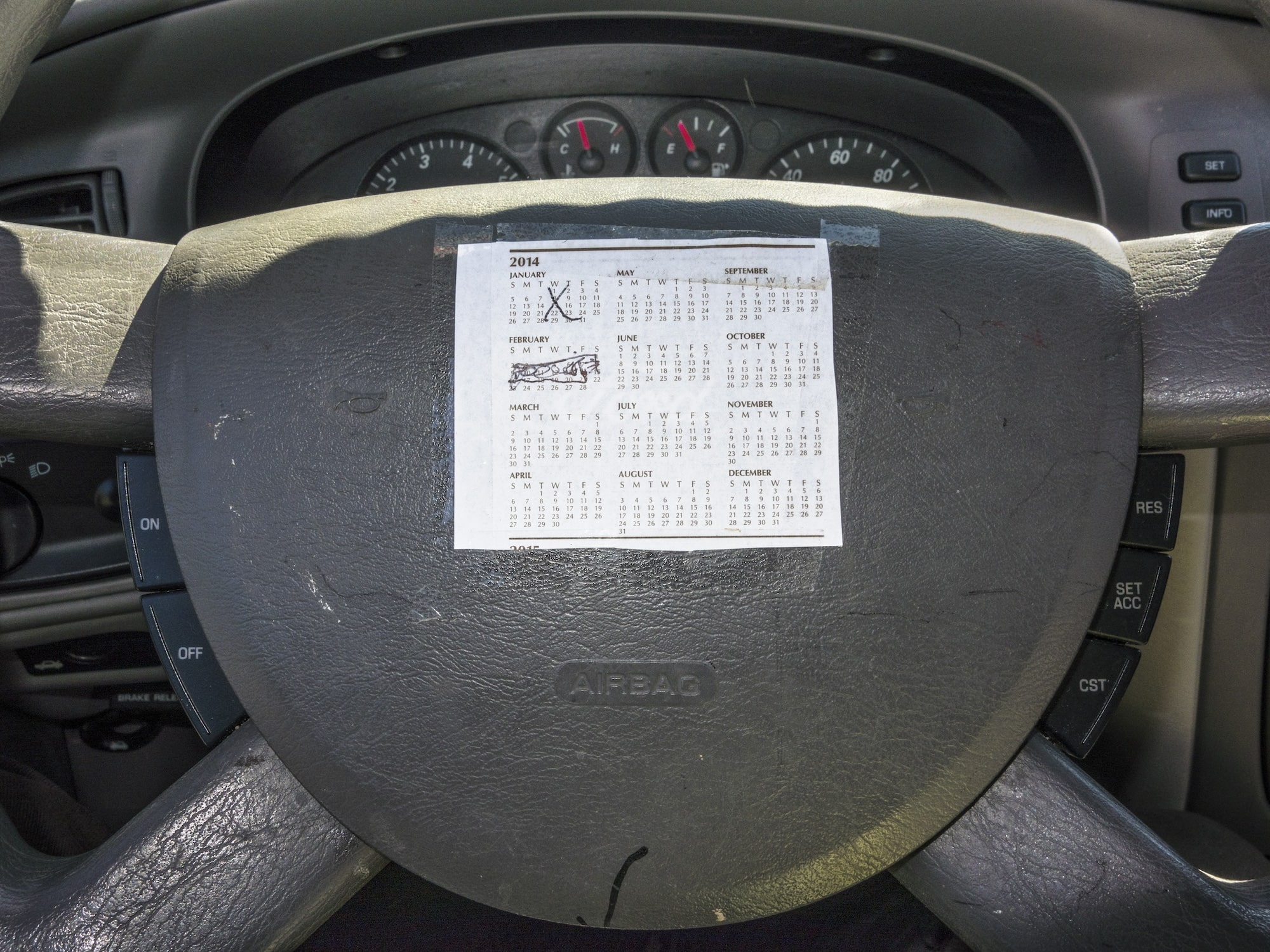

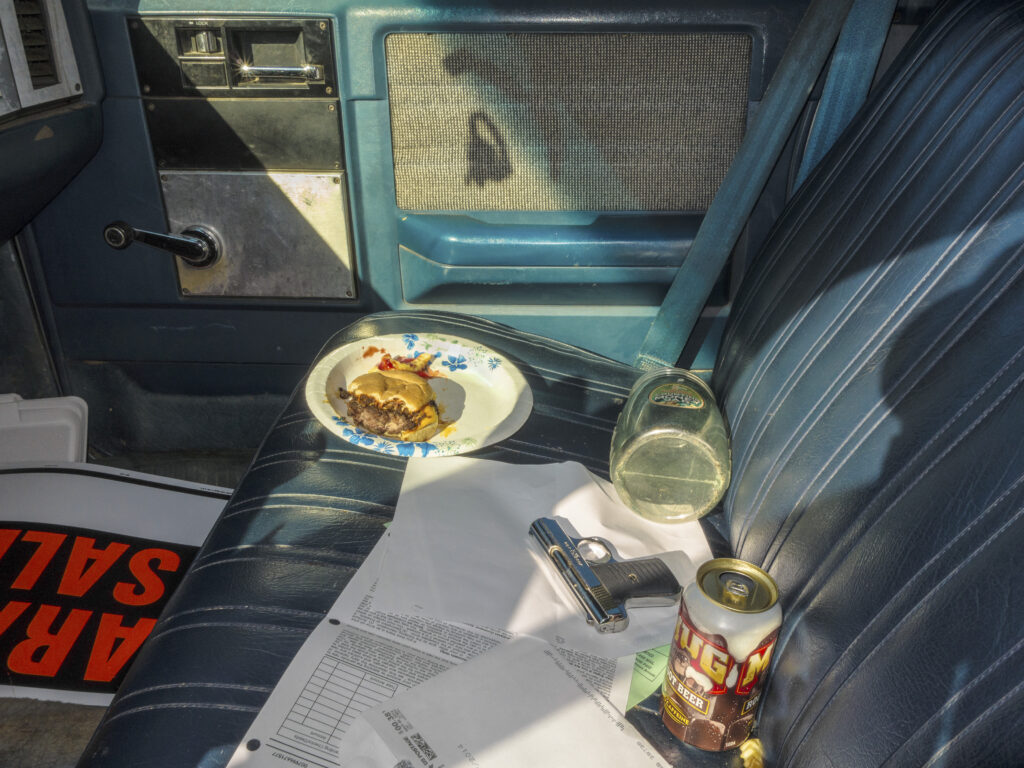

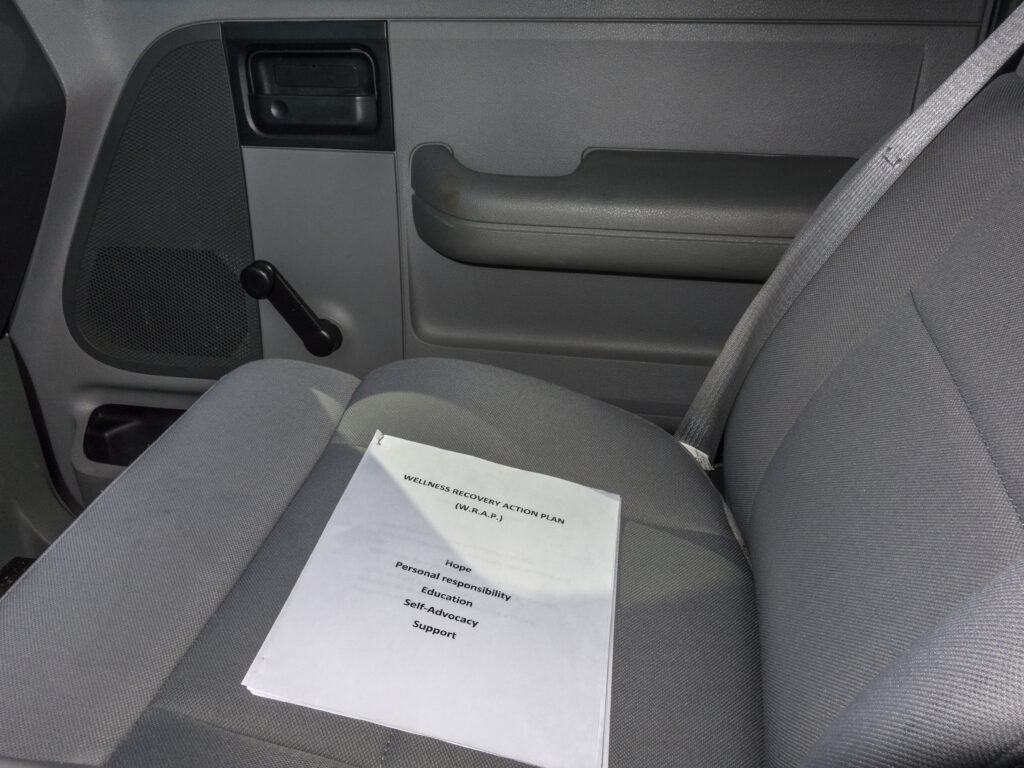

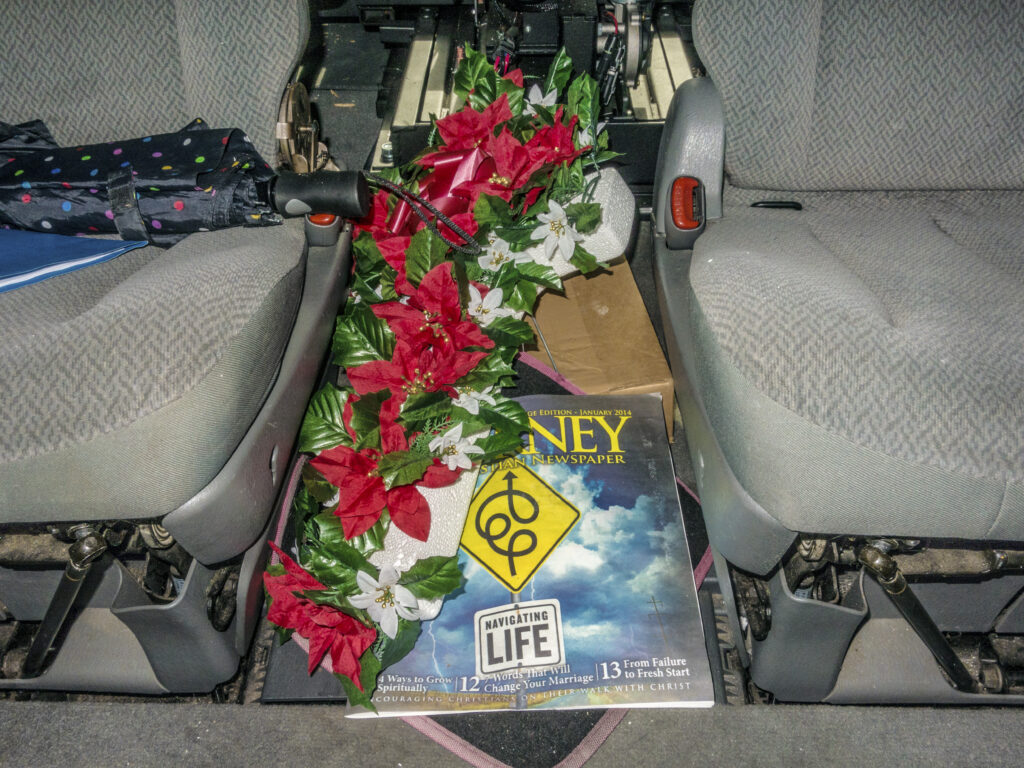

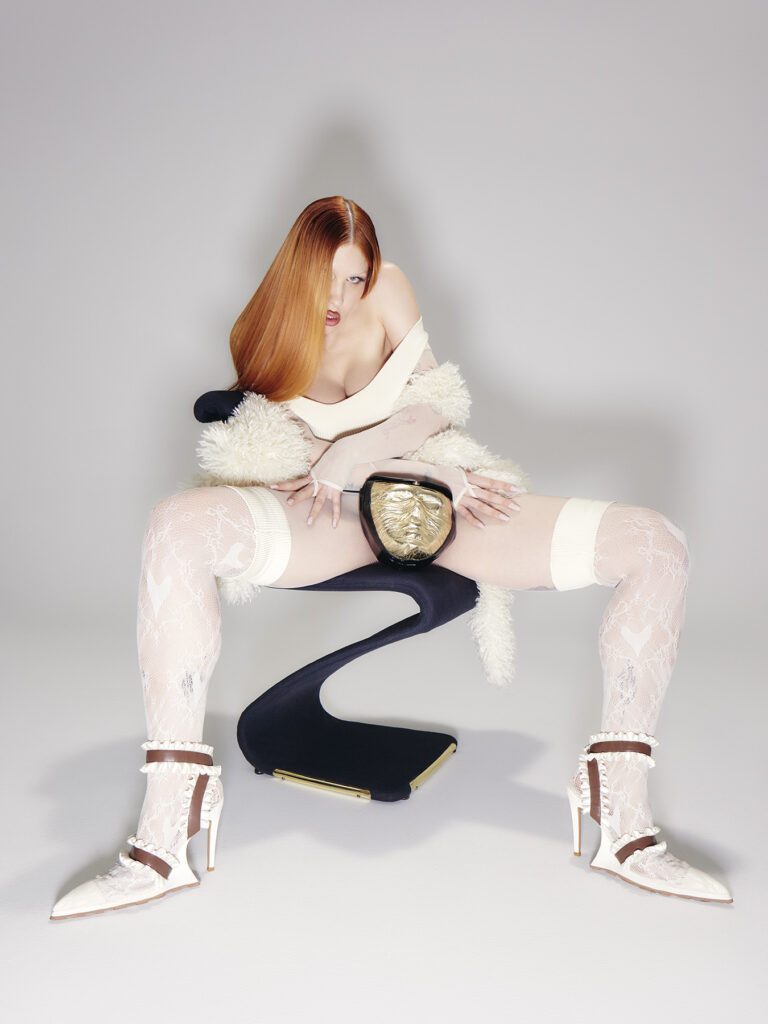

American Interiors

Team

Photographer · Sara Pavan

Art Director · Flavio Crespi

Styling Assistant · Giovanni Tricase

Supported by FUJIFILM, Shot with FUJIFILM GFX100S

Team

Photography · Rita Lino

Styling · Elettra Simos

SFX and Makeup · Greta Giannone

Styling Assistant · Elena Bignamini

Photography Assistant · Irene Guastella

Production · Cecilia Fornari

Special thanks to Marsèll and Loris Moretto

Frankie Pappas is the collective pseudonym for an international architecture and design firm based in South Africa. They describe themselves as “a collection of brilliant young minds that do away with personal egotisms to find remarkable solutions.” NR Magazine joined Ant (I’d rather you didn’t use my surname please) in conversation. Ant is a storyteller, each question revealing more about the work of Frankie Pappas and the ideals and motivations behind the firm, each more interesting and radical than the last.

Nicola Barrett: What was the process behind the creation of House of the Pink Spot and what were some of the challenges you faced on this project?

That building came about because a friend of mine, Alicia, heads up this thing called Digital Disruptors. It’s one of her many projects. She wanted something to do in this area, Orange Farm, Drieziek in Johannesburg. She’d gotten some money and she didn’t know what to do with it. I said, well, I would approach it from an architectural perspective. I’m fascinated by how you can make small interventions in parts of the city and see what impact they have.

There are two stories that I told Alicia. One was of Guatemala. They were having these huge drug wars. I went there maybe ten years ago, just after these drug wars had kind of been quelled a bit in the urban areas. They were trying to reinitiate the use of these public spaces. So they just put massive amounts of really fast WiFi into these public places and a lot of light. When I went there these places were so full, everyone was working in their laptops. It was quite amazing. This idea that once you initiate people into a space, it inherently becomes a little bit safer.

Another story like this that I like, is in Kenya, there is a main road to the airport that is incredibly well-lit. The reason is that the government wanted its dignitaries to have safe passage to the airport and back. I saw this one photograph, and it just stuck in my mind. It’s of these school kids sitting along this road, miles and miles of them because this is the only light they have access to. Doing their homework. And it was just amazing.

These two things stuck in my mind. I said, Alicia, this is probably what I would try to do. Bring light to the space and a hell of a lot of WiFi. Let’s find a spot where this could work. When we were there with GBV survivors and activists, they chose this one spot which was a dumping ground. We got that cleaned up and in essence, built this public park. I mean, it’s very small, but that’s what we had available in terms of the fund. We worked for free on this project because the budget was so small.

The construction of it is really interesting. It’s got to be the tallest building in Drieziek. We ordered the longest telephone poles we could get our hands on, painted them pink on the ground and then hoisted them up with solar lights on top of them. The seating is all just brickwork. It’s very simple stuff. All signage is hand painted by everyone.

The challenges are numerous. The reason why it’s the Pink Spot is because we didn’t want it to be affiliated with a political party. The ANC, which is the ruling party, their colours are green, yellow and black. We went through all the colours of the parties and we were left with purple and pink.

Nicola Barrett: Was it built on private land or public land?

Oh, my word. You’re going to get me into trouble here. I have absolutely no idea.

Nicola Barrett: Did you not come up against opposition when you start building in unclaimed places?

Well, it’s obviously someone’s land. And by someone, I mean, it’s some state enterprise. So it’s definitely not private property. Let’s call it municipal land for the sake of this conversation. It’s municipal land that is not only being under-utilised, it’s not being maintained. It’s a dumping ground.

Surely the city’s land belongs to citizens. I would expect that to not be a controversial statement. But it is. It’s on the bottom of a street that these activists live on. It is like an inherently unsafe space because it’s not being maintained. They said we’re going to try and make it safer for ourselves. We want a way to activate it, to maintain it. All we ask is leave us alone so that we can. Because our governments are so ineffectual, it has to be done by people who care, the citizens. It is like a type of guerrilla architecture.

Nicola Barrett: There are many unused spaces, particularly in urban areas, what’s your opinion of more radical ways of reclaiming these spaces?

I can only speak to it in a South African context. But I’m always surprised at the amount of legislation in the way between what exists and what I would like the city to be like. The offices that I’m in at the moment, this is our first development, because exactly this problem that you’ve spoken about. What we are doing is not by the book. We’ve taken an Apartheid-era house that was not being utilised and we converted it into these six tiny little offices. It goes against every single regulation.

But there’s a market for small office spaces. The smallest office space we can get is 45 square meters. Do we need 45 square meters? No, not really. Then we still have to pay for heating, for lights, for WiFi. Why don’t we do one ourselves where we make a seven square meter spaces and we make five other office spaces for other people with a shared boardroom and we get this thing off the grid so it’s on solar? We don’t need the municipality at all.

If you don’t have the capacity as a citizen to change the city, I mean, what are we doing? I use the word citizen very deliberately because you choose to live in a city, so truly you should be able to change it in some way. It’s liberating, I suppose, in a weird way, to live in South Africa, where the protection of the law is so bad that you can implement this thing that you want to do.

Nicola Barrett: In what ways do you think people with fewer resources could potentially reclaim under-utilised spaces?

This is one of the problems we’re trying to solve at the moment. Providing better accommodation and still making it economically interesting. Think £250 for two-bed apartment. That must sound insane to you. But is that achievable? Can we do it? Yeah, I think we can. It means finding spaces that are under-utilised in the suburbs, that’s easy enough to do because you have garages that are not being used. You’ve got people who are 65 years old who have a four-bedroom house whose kids have all left. Utilising those unused spaces could be done very well.

But the Gherkin can never be done well. In no world is that floor plan divisional. All it supports is big companies. It’s revered as this great piece of architecture by Norman Foster, but it’s a piece of nonsense. But it’s one of the things that’s so frustrating about the architectural world because it’s all about houses for really wealthy people, or big office buildings or the Line. But something like the Pink Spot, I think is a far more interesting project. If you build the Line, you will never be able to change it if you have a normal salary. The way to do it is to parcel land into small enough quantities that normal human beings can create change.

And for architects to get involved in the curation of the city. You cannot be the servant of the rich and you cannot be the barefoot philanthropist, that’s the world. The role of the architect, I think, is looking after the health of the city. And so therefore, as an architect, you should be in the role of apportioning capital to projects that you think are valuable to the future city. The city you’d like to live in, as doctors, should be responsible for looking after the health of humans. Right. But we should afford architects this opportunity or this role. But of course, it’s not done that way. The people who are producing the city are developers who are, in essence working for provident funds or some sort of big capital-allocating entity, and that’s chaos.

Nicola Barrett: House of the Big Arch was designed with not only humans but local wildlife in mind. What were some of the challenges you faced doing this?

I learned to say what is the non-negotiable. And a non-negotiable can be so philosophical and unattainable and unachievable in the beginning and then as long as you don’t move that line, it’s achievable. Can we build this building in a forest without disturbing a tree?

When you produce this very strict problem set, which is; we can’t disturb a tree, we have to get the materials from the closest town, it has to be all be carried by humans. How do we manage these extreme temperatures of 40 degrees? All of these are these very strict parameters that you can’t ignore. And once you are clear about them, it’s almost like linear programming, except not two-dimensional. Like a multidimensional linear programming problem where the problem space is so small that the form produces itself.

This architecture is not a function of invention, it is a function of discovery. Deciding on what those parameters are, that’s the real work. The rest, it just solves itself. Be real about what the problem set is and solve for that. And then you won’t get something boring. Not possible. I’m glad to say that’s the one thing I think all our projects, whether furniture or buildings or artwork, have that in common. Wonderfully similar but beautifully different. Because nothing looks the same. You wouldn’t think House of the Big Arch and House of the Pink Spot and House of the Flying Bowtie are designed by remotely the same people.

Nicola Barrett: So you state that your collective pseudonym challenges the status quo. How so?

This was a joke. That statement is not a joke. But this was kind of poking fun at architecture firms named after the person who owns them. There is this inherent ego in it all. And I find that laughable. For multiple reasons. First of all, like, you have an infinite choice of names and you resort to your own, which you didn’t even choose for yourself. So you are both arrogant and stupid. Obviously, I’m being a little bit facetious, but I’m also not.

I’d read a book by Willard Manus called Mott the Hoople, which is quite a funny book. The titular character’s friend was called Frankie Pappas. And I thought, Jeez, that’s my mother’s maiden name, and I’d never seen Pappas in a book. So I was like, oh, this is funny. And Frankie is gender-neutral. And I thought, that’s interesting, maybe there’s something there. Anyone can be Frankie. But I always laugh when there’s a man that comes through asking for Mr Pappas, and then I’m like, well, that person definitely hasn’t read what we’re about.

And the reason we were in search for this collective pseudonym is that there was a mathematician called Nicolas Bourbaki who was releasing all these amazing papers on math, but it turned out like he was ten twenty-year-olds who had decided to collaborate under this collective pseudonym and they just changed mathematics. I think he is still, to this day, the most published mathematician. He’s multi-generational and we liked the idea of a multi-generational architectural firm in South Africa, because there aren’t that many of them. That’s why Frankie is Frankie.

Nicola Barrett: You state on your website that almost the entire tradition of Western formal architecture has produced sculpture rather than architecture. How so?

I think for a long time it has been the case. Formal architecture has always been something that you have to sell to someone. So whoever is the client, you have to give them drawings and models. It’s very difficult to make a drawing and make someone focus on the stuff that is inside the drawing. Like how the space solves these issues. Or you discuss the sculpture of the model and someone says, I don’t know how that looks. How do you discuss the space inside a model? It’s impossible. Informal architecture has been one of, what do I need? I need to solve this issue. I have another child. Therefore, there needs to be another bedroom. It’s a very practical thing.

I was in a competition and one of the guys was discussing the school he had made. This thing was clad in rock from the area and then one of these rock tiles had been removed, and then they put a stainless steel tile there. And he said, because we wanted the stainless steel to reflect the sky, and so, therefore, the sky would be bursting out from between the rocks. Why clad it in rocks in the fucking first place? There’s this obsession with what the thing looks like.

The most amazing photographs of the Pink Spot are the ones taken by Tshepiso Seleke. He does not give a shit about the architecture. He doesn’t care. He’s just like, there’s a beautiful person. There’s another beautiful person doing something. Doesn’t even look at the building. That shot that he took of those kids with those go-karts is just my favourite thing ever. That’s what I mean. There’s this obsession with what this thing looks like. That’s not the important stuff.

Nicola Barrett: What advice would you give to young creatives working in our architecture and design?

My only advice is that in the contemporary world, I think we are solving a lot of problems that are not actually problems. It’s like this artificial intelligence. This is a problem that is being solved that isn’t a necessary problem to solve. What is the actual improvement?

I suppose the thing is to see what are real problems and identify those as real problems and then solve those real problems. To actually be honest with oneself what real problems are. That’s not easy. We all get caught up in our own world. Taking a step back and thinking, where should I spend my time… Because you’ve got finite breath, right?

Many of us are incredibly doubtful in ourselves, stressed and worried. We think we are not big enough to contribute or to change everything, and we see these problems. But I think there are these small little things that we can get right and we can just try. The Pink Spot, just for the photos of those kids enjoying themselves, that makes it worth it. I always tear up when I see them. It’s so beautiful.

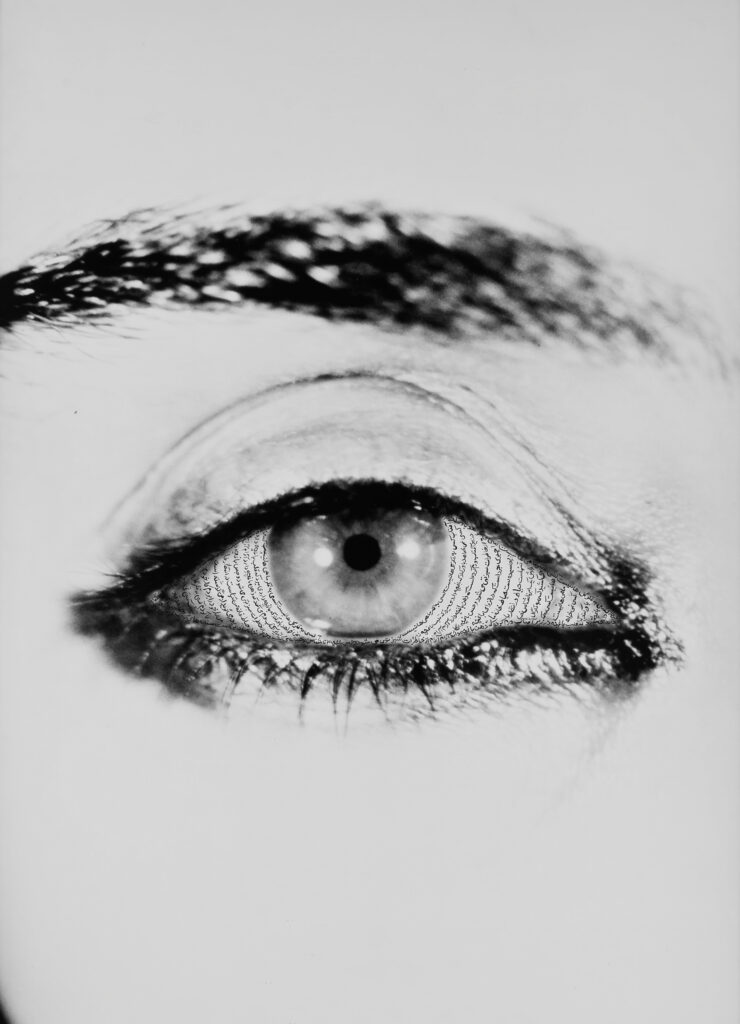

Shirin Neshat (Farsi: شیرین نشاط, b. 1957) is an Iranian-born visual artist who lives in New York City, known primarily for her work in film, video, photography, and opera; directing Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida at the Salzburg. Her artwork focuses on the notion of opposites between the East vs. West, femininity vs. masculinity, spirituality vs. violence and the beautiful vs. the disturbing; highlighting the contradictions between these subjects, through the lens of her personal experiences of exile and finding a sense of belonging.

She has exhibited her work internationally at numerous museums and galleries, including: the Serpentine Gallery, Stedelijk Museum, Hamburger Bahnhof, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Faurschou Foundation, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and Museo Correr, which was an official corollary event to the 57th Biennale di Venezia in 2017. Neshat’s Turbulent was awarded the Golden Lion Award, the First International Prize at the 48th Biennale di Venezia (1999). Her first feature-length film, Women Without Men (2009), received the Silver Lion Award for Best Director at the 66th Venice International Film Festival. Her other feature films are Looking For Oum Kulthum (2017) and most recently Land of Dreams (2021), which premiered at the Venice Film Festival.

In concurrence with her recently released short film and exhibition The Fury, NR Magazine spoke with Neshat about her memories of her childhood, transition from working between different mediums, working with subjects originating from the Middle East to the US, and about the excitement of embarking on her most recent projects.

Dara: I would like to start by asking you about your early memories of your childhood growing up in Iran and later moving abroad.

Shirin Neshat: I grew up in one of the more religious cities in Iran, Qazvin, with a lovely family. My father was a farmer and a physician, and my mother was a housekeeper. We were 5 children, and we had this dream life in a home with a beautiful garden. Therefore, my early life in Iran, up until I was 17, was quite normal and peaceful. I left Iran at the age of 17 because my father, like many other Iranian families at the time, wanted me to continue my education in the West. So, I came to Los Angeles with my sister, and that was a pretty dramatic transition for me. This was because the image I had in mind of America and what had been depicted for me was very different from what I saw and experienced, which caused me to fall into a depression. This period was in 1975, a few years before the Iranian revolution, and I remembered I really wanted to go back to our small town because of how ill I was feeling leaving the proximity of my family.

Unfortunately, my father was quite persistent for me to stay, and shortly after the revolution happened in Iran. During this period, I had just turned 20 and began my studies at UC Berkeley. Therefore, the early days of my studies in college coincided with the revolution taking place, followed by the war with Iraq that led to the breakdown of diplomatic relationships with the US, and my total isolation from the rest of my family due to not even having remote family in the US. This experience was quite horrifying as a 20-year-old who never really felt comfortable living here, and this feeling was perpetuated by the inability to communicate with Iran through post or telephone service.

Therefore, my early memories of my childhood in Iran were quite peaceful and happy, but this quickly transitioned into a very dark period of my life was quite traumatic, as I’m sure many other Iranian people that experienced this separation could relate to. During this time, I suffered from anxiety and was stuck in this constant feeling of being ill that caused me to not perform well in my studies. I think this period, from when my sister left back to Iran a few years prior to the revolution until when I eventually moved to New York in 1982, was the most difficult period of my life.

After moving to New York, I started to finally find the right community, and I married my Korean partner at the time, which led me to join him in running a non-profit organization dedicated to art and architecture. Starting this new life in New York was hard at first because I didn’t know anyone and had no money, but due to the nature of the city, it allowed me to find a sense of security and community. During this period, I didn’t have the opportunity to go back to Iran and see my family for 11 years, partially because of the war between Iran and Iraq and the diplomatic breakdown between USA and Iran, but I finally had the opportunity to go back in the early 1990s.

The reason I explain this background is that it has a lot to do with the art I create, and the emotional, psychological and even at times political substance of my work. My work is a reflection of the sense of exile and loneliness I experienced during this period, and the anxiety and alienation that came from that. Therefore, many of my characters in my films are very representative of these feelings. Following my return from Iran in 1996, due to me beginning my work as an artist, I have been unable to revisit ever since.

Dara: I can’t imagine how difficult this transitional period was for you, especially considering all the events that took place during that time in Iran. I’m sure many Iranians moving abroad prior or during this time can relate in their own way to the feelings you’ve shared. I’m curious to hear more about your experience of visiting your family for the first time after over a decade, and how this experience felt and influenced your work that followed.

Shirin Neshat: It was both exhilarating and horrifying. I remember during this time my son was born; he was 3-4 years old and had a Korean-Iranian background. It was kind of strange after 11 years because there was a distance between the life that I had lived and the life that my family had lived in Iran. There had been so much that had happened: the revolution, war with Iraq, and the economic situation that had followed, which caused a gap between us that was hard to distinguish for me – understanding who they were before and who they were now.

On a public and societal level, everything had transformed, even visually. It was almost as if the color had been lifted off the cities, and everything had become black and white. In some ways, I felt excited because I felt the life that I had lived during this time away was so meaningless. I thought my life during this time was so individualistic and so much of it was about me caring for only myself. Being in an environment where people had suffered so much, in the early 1990s where all these events had taken place so recently, and having the opportunity of seeing and reconnecting with many of my old friends, I finally could try to understand and feel what had just happened. I had the opportunity to read books and material on all the events that had taken place, and also hear experiences to try to immerse myself in this time that had already passed.

Therefore, when I returned to New York, I found it really difficult because my heart was no longer in working on our non-profit organization with my husband. I just really wanted to go back again and I did a few times until I had trouble being able to visit. All of these interactions, impressions, and inspirations I had during my visits to Iran ultimately culminated into my art. What many don’t understand is that prior to these initial visits to Iran, I wasn’t an artist, and I was mostly interacting with art through helping other artists in their practices. But I realized that all I wanted was to connect with Iran and what I had just witnessed during my time there, and art very organically became this connector and a great tool for raising questions or creating a dialogue with all the issues I found interesting.

I believe that there was a misunderstanding of people thinking I was trying to make a statement or claim towards the events that had taken place, but this was never my intention. I knew very well that I was an outsider, and my intention with my work was to focus on a subject that interested me, and I would try to research that idea. For example, with Woman of Allah (1993), I read my friend’s philosophy thesis on the subject of Martyrdom (Shahâdat) in post-revolutionary Iran, and I was mesmerized by his analysis of the correlation between love of god in religion and the violence in death. To me, this was an incredible paradox that inspired me to make that series of photographs,. To this day, I’m attacked because people think that by creating this body of work I supported the fanaticism of the current regime, and on the other hand, the government thinks that I was critiquing the regime. My intention with this body of work was to raise questions on a very symbolic and conceptual level.

My artwork was triggered by my return to Iran through my experiences and inspirations during these visits, and it grew from there very organically from one medium or topic to another.

Dara: What really moved me about this body of work, Woman of Allah, is the juxtaposition present in the heaviness felt in the composition of the images and the use of calligraphy, and on the other hand, the sense of vulnerability felt through the presence of the woman’s body. As a viewer, I found myself positioned at the center of this paradox. Can you further discuss your position and process behind this series and your decision to use calligraphy in your work?

Shirin Neshat: You have to keep in mind that I was educated in the West and due to this, I developed a Eurocentric background in my relationship with conceptual art. On the other hand, my subjects are very rooted in Islamic and Persian art and architecture. If you look carefully into my work on an aesthetic and visual level, you notice an emphasis on symmetry, repetition, harmony, and integration of text. There is a reference to sacred text experienced in Persian poetry and Islamic architecture. Therefore, many of my ideas are borrowed from authentically traditional Persian and Islamic art that points to my heritage, but the language of my work is very much that of conceptual art. I grew up influenced by the work of artists like Cindy Sherman and artists who were predominantly working in self-portraits. Therefore, the enigma and abstraction that are present in my work are not coming from traditional influences but my experience of Western conceptual art.

The paradoxical sense of duality you mentioned about Woman of Allah and my work at large comes from my subconscious strategy of finding contradictions, opposites, and paradoxes in the work I create. This duality is evident in Turbulent (1998), Rapture (1999), The Fury (2022) and my other work as well. These conflicting ideas and notions of opposites, for example, men vs. women, spirituality vs. violence, the beautiful vs. the disturbing, or open natural landscapes vs. controlled fortresses, both aesthetically and conceptually influence my work, ranging from photography, film and opera. This duality is represented in my emphasis on working in black and white, juxtaposing realism with surrealism and dreams, and has stayed constant throughout my work.

Dara: Before we move on to your films and your transition into moving images, I want to take this opportunity to further discuss your body of photographic work, such as The Book Of Kings influenced by social and political movements throughout the Middle East.

Shirin Neshat: Over time, I realized that subconsciously I found myself referencing history in my work. For example, The Book Of Kings (2012) was influenced by the Green Movement, Women Without Men (2009) was influenced by the 1953 Coup, and Looking for Oum Kulthum (2017) was influenced by Egyptian history during my time there in the Arab spring. I tend to approach history in a very fictionalized way, and in The Book Of Kings there is a focus on this notion of patriotism influenced by Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (Book Of Kings), which is a long epic poem of tragedies that focuses on the core narrative of these heroes that self-sacrificed for their virtues and their nation. Ferdowsi’s book is largely credited for saving the Farsi language following the Arab conquest that ignited the introduction of Islam in the Middle East. Also, The Book Of Kings is influenced by the more recent Green Movement in Iran, which was a forward-thinking movement not focused on religion, and people demanding a new idea of liberty while not overthrowing the government. These powerful notions of the spirit of patriotism that later on continued throughout the Arab spring tend to always intersect with genocide, violence, and cruelty, similar to what is present in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh where you read about men’s heads being severed. I found this tension between compassion and love for the nation, and the brutality, violence and genocide that came with it incredibly moving and profound. I represented it in this series of photographs through symbolic gestures such as having a group of patriots with their hands over their hearts, a group of villains with scenes of war from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh inscribed on their bodies, and a group of 45 images depicting innocent bystanders observing this circus. My intention with the series of photographs was to capture the spirit of patriotism during the Green Movement in 2009 and for it to serve as a remembrance for those who lost their lives, and also as a reminder that history tends to repeat itself.

Dara: It’s interesting to hear you move from such a personal subject so close to you to a more expansive conversation with a wider audience throughout the Middle East. I’m curious to hear why you decided to transition from photography to moving image as a medium to continue this discourse. Also, as a starting point, I wanted to ask you about your first short film Turbulent and your application of music as a communicative tool throughout this project.

Shirin Neshat: I think after Woman of Allah I received such a dogmatic response to it as a project, a response that was quite political and the judgment was so heavy. This experience made me feel that the nature of photography limited me from building more ambiguity, and to be able to take the audience to a place where they were not forced to impose their relationship to the subject of politics. Therefore, transitioning into moving images felt like a massive departure for me. It opened a new door to a whole new medium that refused to be reduced to these types of judgments because I had the opportunity to be far more evocative and abstract – even if my work was politically charged. The other advantages this new medium offered were the opportunity to set a background or a landscape, and to introduce music and choreographed performances. Also, it gave me the ability to situate my audience to have them experience it in a way that I could control as an artist.

With a photograph, as a viewer, you are placed in a situation where a single photograph has to say everything. This became quite difficult and problematic for me because most of the time, that image is reduced to a few symbols such as a veil and a gun, and this leads to the loss of every other complexity present in the work. Therefore, I found my transition into film as a beautiful new and freeing journey. Turbulent focuses on critiquing the sociological issue of women in Iran being deprived of the experience of music. It does so by again placing the audience in a conflicted point between two opposites: one being a man performing a song to an audience and being applauded for his performance, and on the other hand, a woman performing alone with no audience, and her performance escalating into a form of protest. But this is the impression that is first felt on the surface of the film. Gradually, there are these layers of meaning that begin to show themselves below that surface. There is a conflict between the conformist and the rebellious, but also between tradition and the act of breaking away from that tradition; to start something new. What I loved about Turbulent was that I felt that my audience, from every corner of the world, got it and truly understood it, and I didn’t have to say anything in that process.

This was a great realization for me that moving image and all the qualities that it comes with granted me the opportunity to create experiences that are far different from what can be achieved with a photograph. This made me step away from photography for a few years and make other films, such as Rapture, which again introduced a paradox through two separate screens; one showing a group of men in a fortress and the other showing a group of women in nature. But at the end, the audience understands the message behind this enigmatic film, which was that the women started this journey from where they started and end up in this boat that they depart in and leave, whether to commit suicide or reach freedom, but the men end up staying and being left behind in the same place. So there was this symbolically calculated outcome that was delivered through form, shape, music and poetry leading to an end that evidently had its sharp knife.

This quality of progression in storytelling in moving image inspired me to continue making many more films and staying away from photography. When I finally decided to return to photography, I had a completely different approach to it as a medium.

Dara: I found your use of two screens in these films quite effective because, as a viewer, you find yourself in the middle of two subjects that are having a dialogue with each other. This experience can be quite emotional and moving, but can be quite overwhelming and uncomfortable as well. Sometimes, you get one screen focusing on one subject and the other giving you a wider context of the surrounding scene or environment. I found this duality in the experience quite powerful.

Shirin Neshat: As mentioned earlier, all my films are built around the notion of opposites, and having the two separate projections only adds to that. The audience cannot watch both screens simultaneously, and they become an editor that has to make a choice. When they focus on one screen, they are missing something else on another. I like this idea of forcing the audience to be a true participant and to be drawn in by the device that this film has created, hence becoming a part of the film. This experience can sometimes be quite uncomfortable for the viewer.

Dara: I felt that sometimes we, as viewers, make the decision of where to look subconsciously. We get drawn into a particular scene and want to continue to follow that narrative and subject. I found myself watching parts of the film again because I had completely lost sight of what was happening on the other screen. I think this ability to have a choice to follow what you connect with is quite freeing.

Shirin Neshat: The viewer’s role becomes much more active. They are not just passive recipients of the content; they become engaged participants who are making decisions and interpreting the narrative in their own unique way.

Dara: I want to ask you about some of the other films you worked on, moving onto doing full feature films and switching from black and white to colour.

Shirin Neshat: When I work with a medium for some time, I end up in a place of stagnation, similar to how I felt with photography. Also, I felt a bit exhausted from only working within the art world because everything was more or less focused on commodity, and you were valued based on how much your work was worth. At this point, I received an invitation from the Sundance Film Festival asking if I was interested in making a feature film, and my immediate answer was no. But after reflecting on where I was at that moment with my artwork, I realised that I was at a point where I wanted to take a new risk. This led to Women Without Men (2009), which is based on a book with the same title by Shahrnush Parsipur. It took six years for the film to be made.

I think the opportunity to make feature films was interesting for multiple reasons. One was the ability to connect more with popular culture and to show my work to an audience that may not necessarily know me as an artist from galleries and museums. But for the most part, I wanted to know if I had it in me to make a feature-length film. So, it became an education for me over the years, working with different scriptwriters and learning how I could invent my own language in cinema by borrowing from what I’d done previously in my work as an artist, while fully embracing cinema as a medium.

Although I had received a lot of criticism telling me to stay in art and not to take the risk going into cinema, Women Without Men was quite well received and this motivated me to keep pushing making more feature films. My next project, Looking for Oum Kulthum (2017), was much more difficult because I was making a film in Arabic about an iconic figure in Arabic culture. As a non Egyptian and someone that didn’t speak Arabic, making this film became a tremendous effort. This film became semi biographical and semi artistic, and I wouldn’t say it was fully successful. But I believe none of my work had come without their flaws, yet I never regretted making them.

My next feature film was Land of Dreams (2021), which was shot in New Mexico staring Matt Dillon, Sheila Vand, William Moseley, Isabella Rossellini, Christopher McDonald and Anna Gunn, was one of my favourites because I had learnt by this point how to direct and how to think about scriptwriting in a way that I didn’t before. I had the opportunity to work with Jean-Claude Carrière alongside my husband Shoja Azari to create an original story, which was humoristic and based on my own ideas. This process lead to me being very happy with this film, and I never expect to make films that are main stream but for them to be very uniquely a manifestation of a visual artist.

With Land of Dreams, it was the first time that I simultaneously did a feature film, 110 photographs, and a double channel video projection. It all came from my obsession with my own dreams, and followed a three part video project I did two years prior called The Dreamers, which depicted my own nightmares. So Land of Dreams came from taking that obsession and going after other people’s dreams and nightmares. There was a parody about America being the land of dreams; this place where people come to make their dreams into reality, which I believe is true in many ways. I wanted to play with this idea of me going after Americans dreams and collecting them. In doing so, questioning if dreams are a manifestation of our fears, which I believe that they are, and what the subjects are fearful about.

The video that is part of this project involves this strange colony inside of a mountain where all these Iranians are busy analysing Americans dreams. The same actress I worked with in Land of Dreams, Sheila Vand, acts as a spy for the colony, going into a near by town, pretending to be an artist asking American’s whether she can take their photograph, later asking them about their most recent dream, and then taking this information back to the colony.

But with the feature film itself (Land of Dreams), We took it a step further where she (Sheila Vand) is working for the American government’s Census Bureau, and that the Bureau has made a new requirement that, along with regularly requested data, every citizen is asked to share their latest dream. This concept is rooted in my interest in the way governments and corporations are using surveillance to develop an understanding of our subconscious. There is a humoristic but also disturbing side to this film; in the fact that we ourselves are targeted by people in power, whether governments or corporations, to be controlled. Also, the film focuses on a main character who is an Iranian woman and an artist, which is based on myself, that is quite haunted because of personal and political reasons.

Therefore, Land of Dreams ended up being quite layered sociologically in regards to America, but also on a individual level. I think with this film we did well in terms of developing a script or story that is very concise, while having many layers and enigmatic subjects. There is a true balance between humour and absurdity in this film, but also between what our ideas where and what we were able to convey.

Dara: This is a good point to ask you about your latest work The Fury, your process of making this short film and your decision to go back to the two screen installation experience.

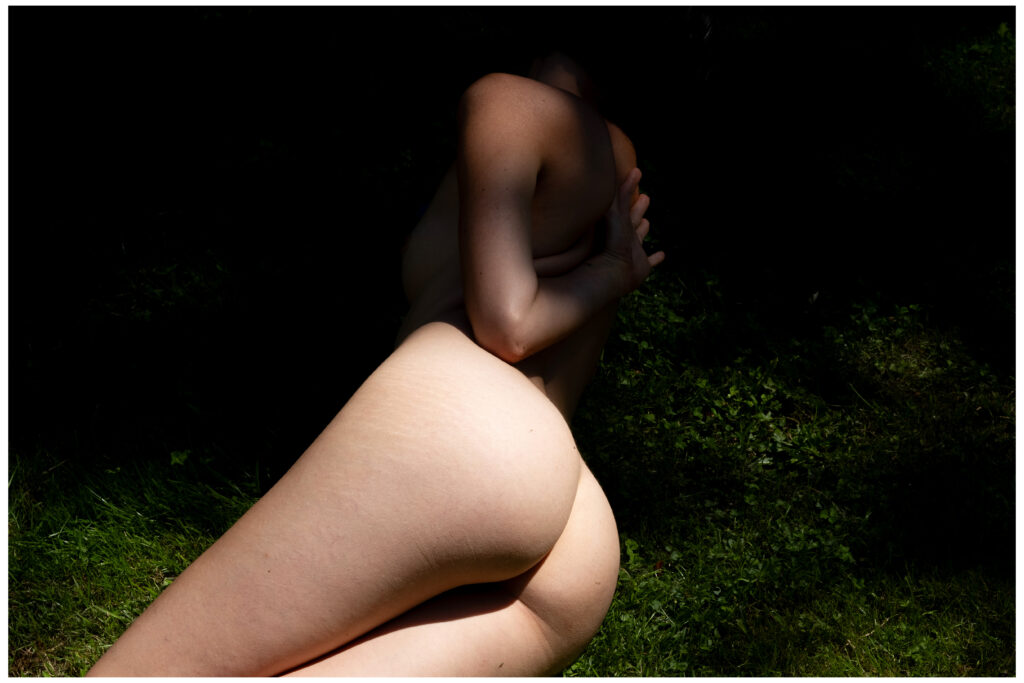

Shirin Neshat: The Fury (2022), in some ways, goes back to the same nature as the Woman of Allah, which is something I tried to stay away from because I knew that if you get close to some of the issues in Iran, people tend to come after you. However, I was influenced by the testimonies shared during Hamid Nouri’s trial in Sweden about women’s experiences in prison, similar to what is being shared today, and how even some of them ended up committing suicide after they were freed. Also, it is important to mention that this film was shot in early 2022 before the recent events that have happened in Iran following the death of Masha Amini, even though many people think this film was influenced by these more recent events. I was very interested and moved by the psychological and mental breakdown of women who are traumatized by sexual exploitation, and due to my consistent focus on the subject of women and how the body of women is used as a space for ideological or religious discourse. In a sense, women are forced to embody the rules of men.

In the case of The Fury, this idea evolves much more into the concept of the women’s body both being the subject of desire, but also of violence and brutality. I wanted to tell a story from the perspective of a person outside of Iran, and the story of a woman who can no longer cope with her reality and goes mad. I referred to my own experience of living among a large Hispanic community in Bushwick, New York, which are hardworking people and come from poor backgrounds. Sometimes, I found myself walking in the streets, listening to Persian music, and feeling like an alien, asking myself what I’m doing here. I experienced this feeling of displacement or disconnection from living among a foreign community, all the while constantly thinking of Iran.

With The Fury, I wanted to create a work that emphasized this experience of displacement, conveying a story of a woman who feels completely out of place as soon as she walks out onto the street, while going mad in her head because of all the traumas she’s dealing with. She’s living inside her own head, and you can get a sense of this early on in the film from her dancing by herself to no particular person. My intention was for the film to progress into a flashback of a trauma where, in order to survive and not be killed, she had to dance nude in front of a male audience – and this is in no way comparable to what women experience while being incarcerated in prison. In the film, the men never actually touch her, but they are brutal in their gaze towards her. When she finally escapes their gaze and runs outside into the middle of the street, she reveals this sense of vulnerability. What is very profound at this point is that all the people on the street who are initially shocked by seeing her outside end up coming to her rescue. This is something I’ve felt in my own neighbourhood; even though the people I live among and I are worlds apart, if anything were to happen to me, these people are my community and would go out of their way to help me because they are good people. To see this community come to her rescue and it turning into a form of protest or dance, in an uncanny way, is exactly what happened after Mahsa Amini’s death. Her death became an impetus for the unleashing of other people’s rage because we’re all angry and we’ve all experienced some form of injustice. Therefore, it is an opportunity for everyone else on the street to also express their pain and anger, turning the scene into this fury. For me, it was about how the pain and suffering of a single human being can be contagious, unleashing our pain, and that we are all ultimately part of one humanity. Many of the people cast in this scene are my friends and members of my community, making this project quite personal to me.

I didn’t want to create a work that tells you what is right or wrong, but I wanted this work to place emphasis on the idea of power, the male gaze, and the vulnerability of this fragile body. The idea that we can all be fragile in the hands of power, but when bad things happen to certain people, it affects others as well and that is our greatest weapon. I received criticism for the assumption that I was labelling all women as victims, and I do not believe in the notion that all women are victims. However, Mahsa Amini was a victim because she was killed and all the other women imprisoned or killed are victims. That is the reality, but the other reality is that we respond to that because it is unjust and unacceptable.

I believe that The Fury has a very bright light at the end of the tunnel, meaning the connection between people, no matter where they come from in the world. Even though they may not fully understand what has happened to her, it causes them to come together in solidarity with her.

Dara: Shirin, I want to finish by using this opportunity as a platform to ask you to share a message with women, especially Iranian women, that are practicing art and are pursuing their creative journeys today.

Shirin Neshat:Firstly, I believe that art shouldn’t be anything else than an obsession that you are at its service. Secondly, I often think about liking myself more when I’m vulnerable, and not liking myself when I’m not. I think it is important for women to allow themselves to be vulnerable, and look at their vulnerability in a positive light because by doing so you are more truthful and can make art that is more truthful as well; art that leads to other people seeing their own vulnerabilities in your subjects. Unfortunately as Iranian women we’ve had so many setbacks, and when we make art there are so many expectations and judgements towards us. Therefore it is so important for us to go within and connect with our internal world, and not care too much about the external world. This is a way for us to check what is so pressing within ourselves to bring out and share with the world, and if there isn’t anything at that moment we shouldn’t do so. Leading to my final point, I hate to say it but mediocracy is the worse of it all and we don’t need to contribute to mediocracy. It must be work that we absolutely feel the need to do and bring out because it has something significant to say and is asking us to be brought out into the world. Otherwise, be patient and don’t rush it.

Dara: I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for being a part of this issue with us. It has been a pleasure to have this conversation with you, and I hope it will move and inspire our readers the way it has done so for me.

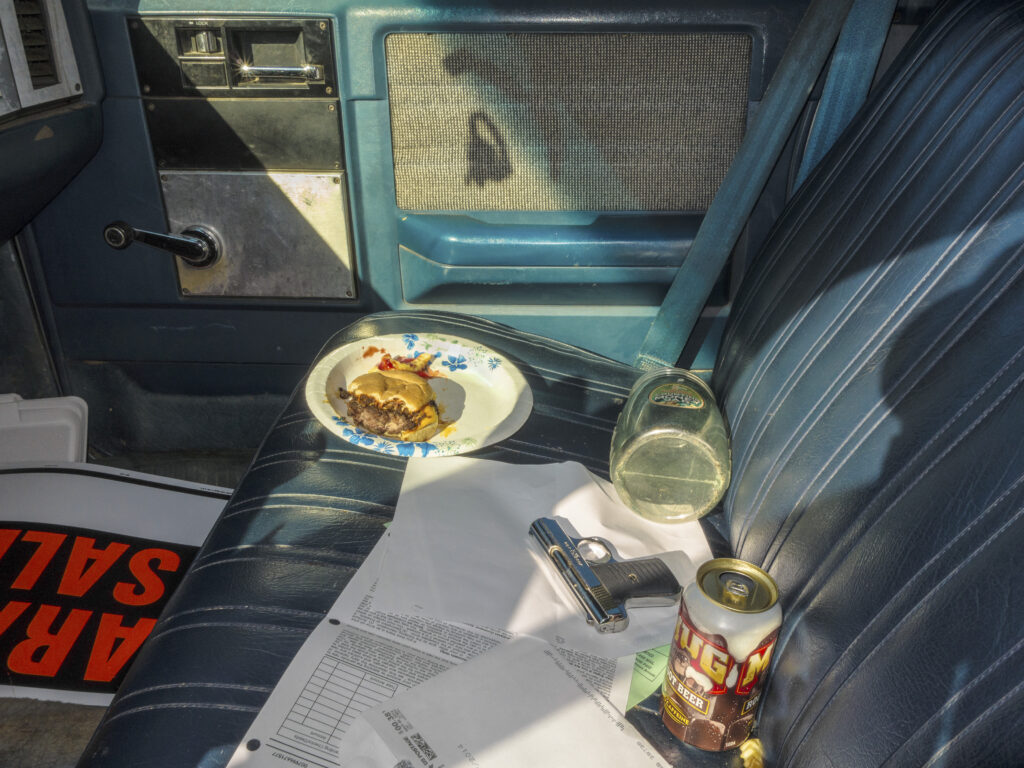

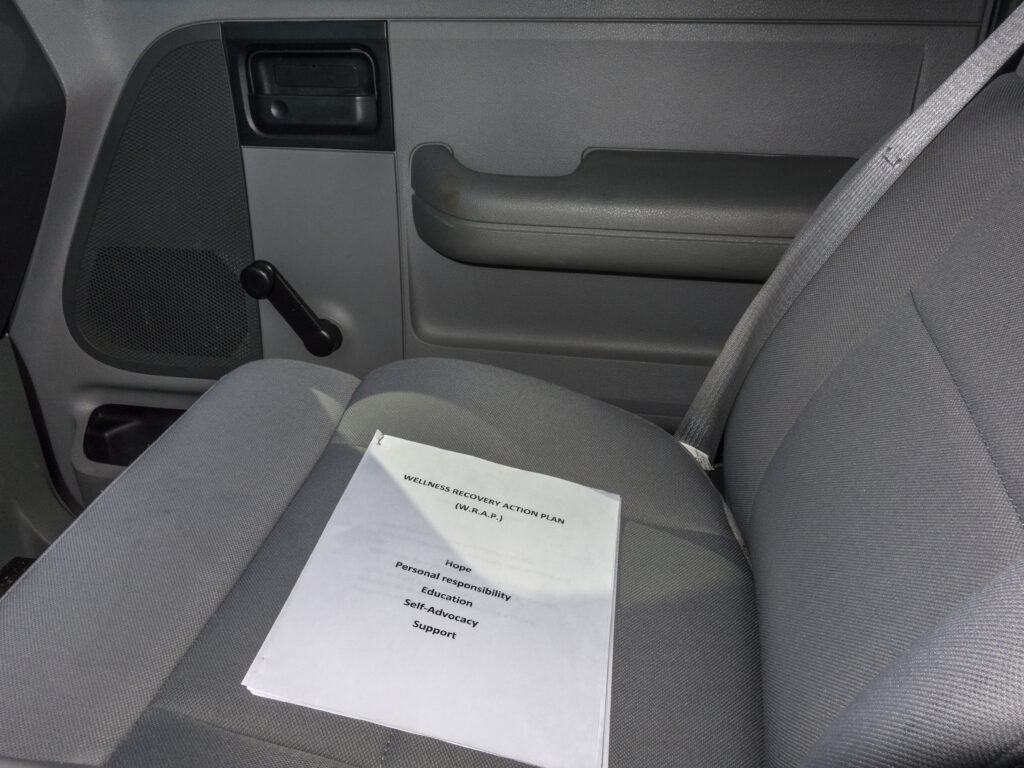

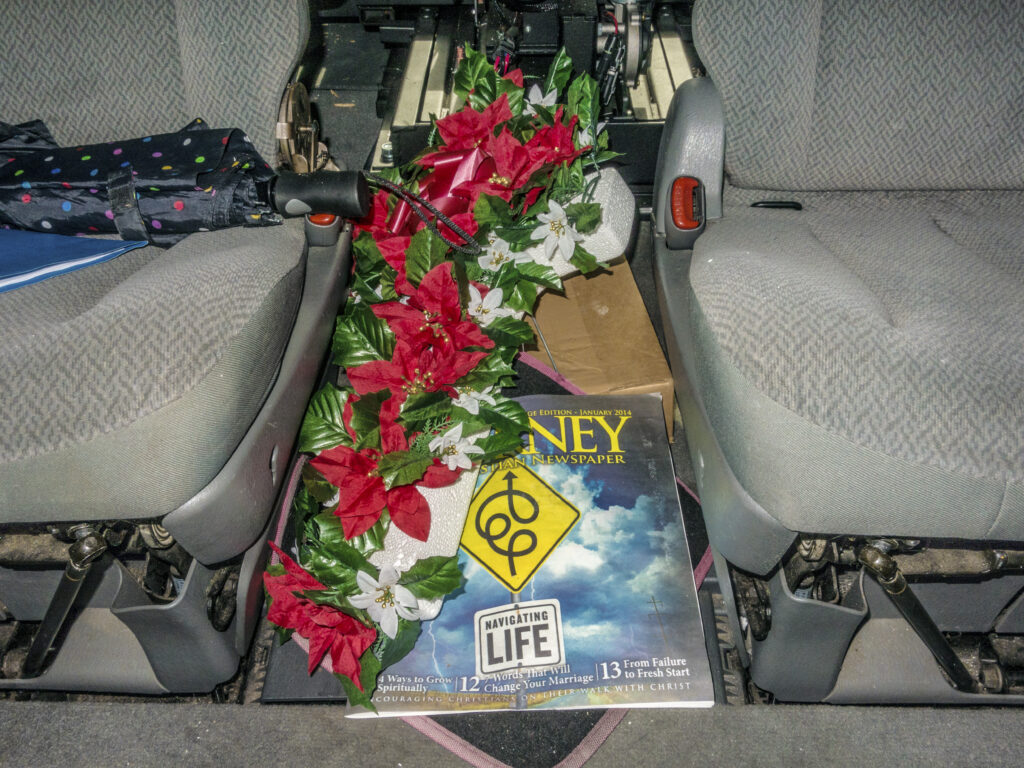

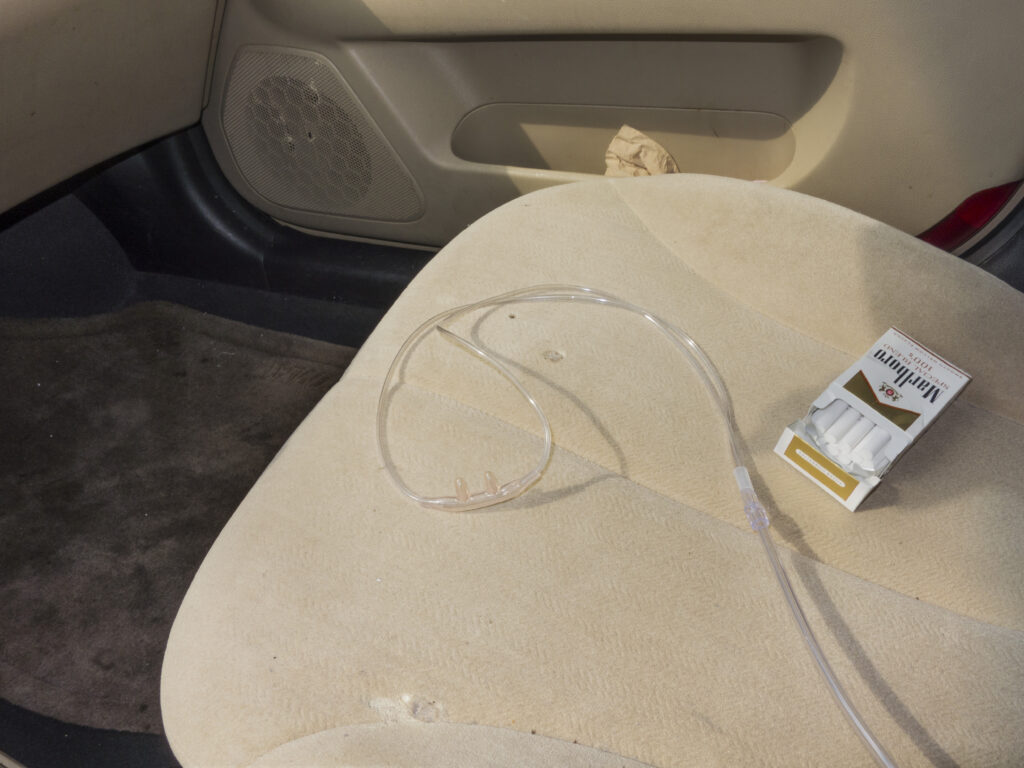

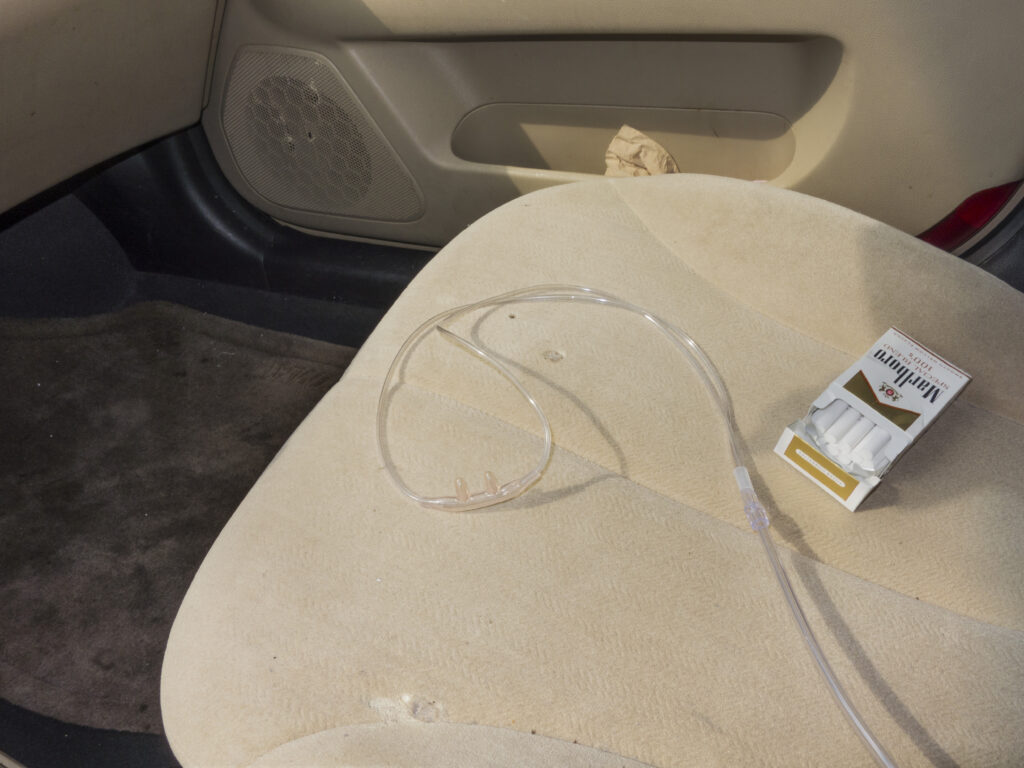

The engine is off and the streaked windshield faces away from but towards. The faded parking stall lines of the empty lot are blanks waiting to be filled in by old habits, starved but undying. Between the spaces where things fall, the seat and the idle transmission, things get lost and lose their edges, soft callused hands reach for absent haunts, memories of. Then the pedal is released. Other cars whiz by, towards, but away from.

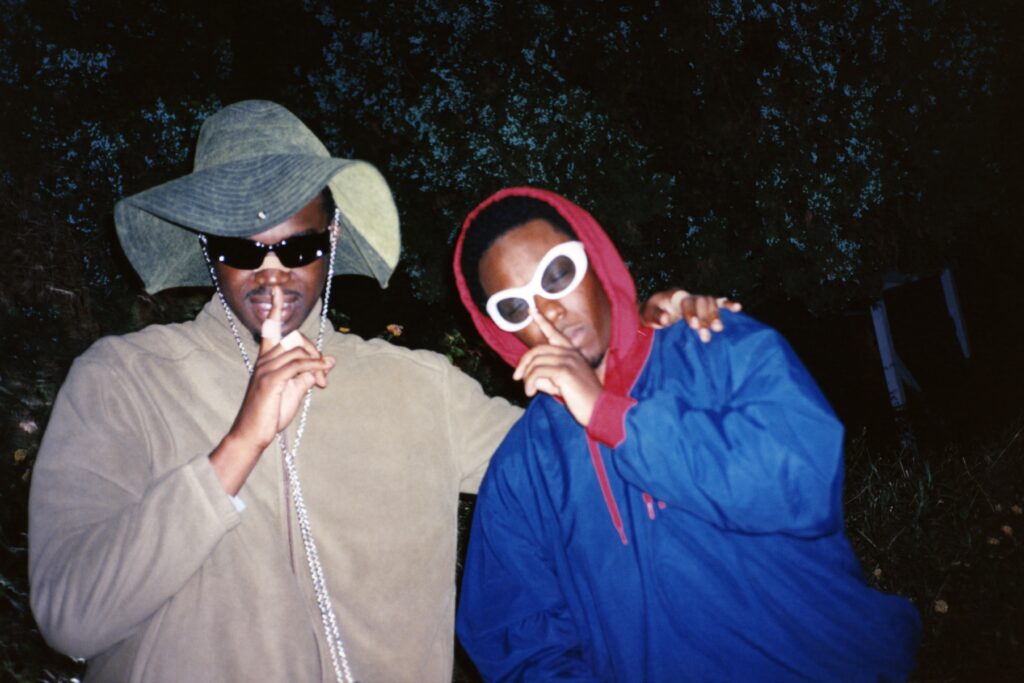

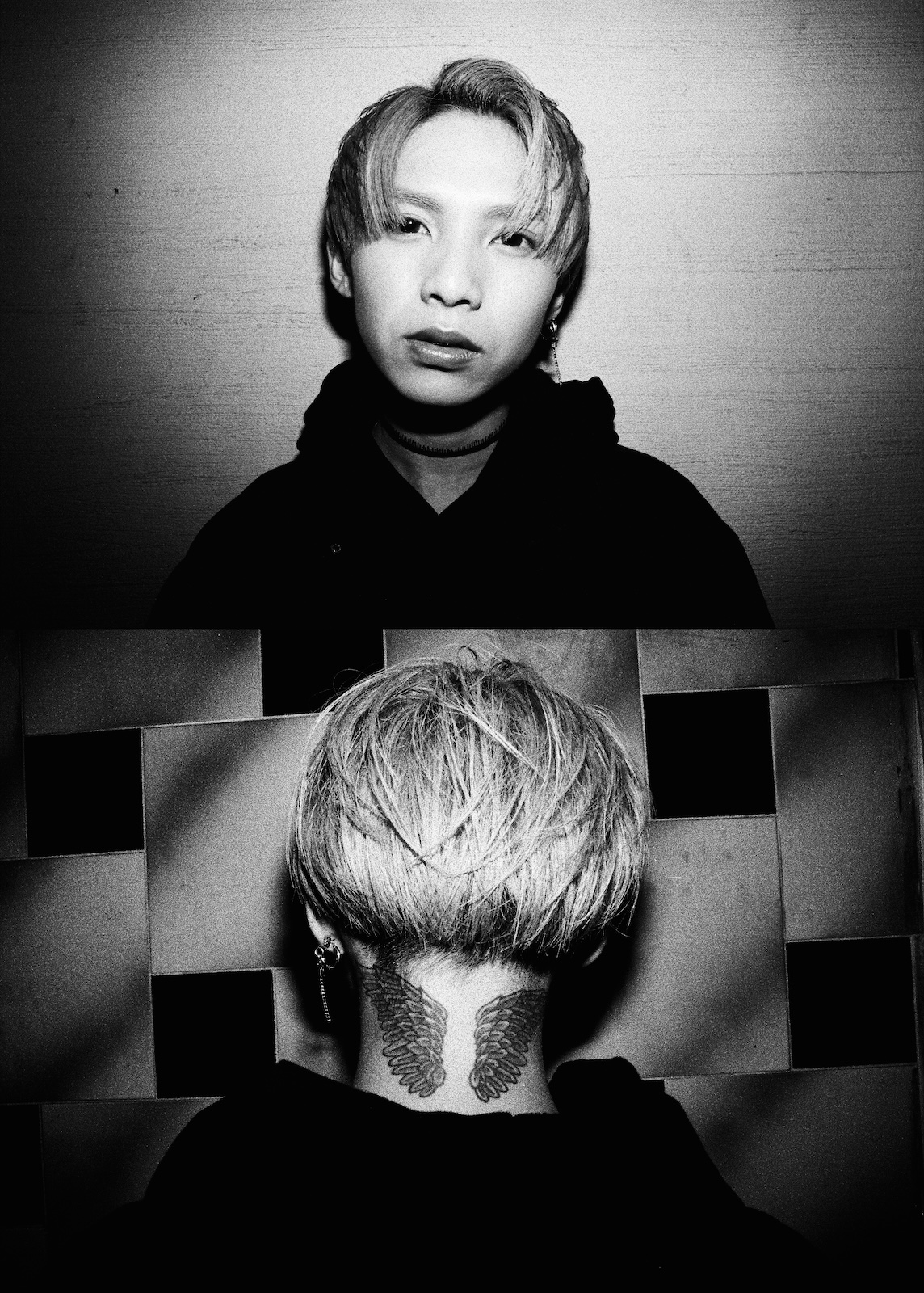

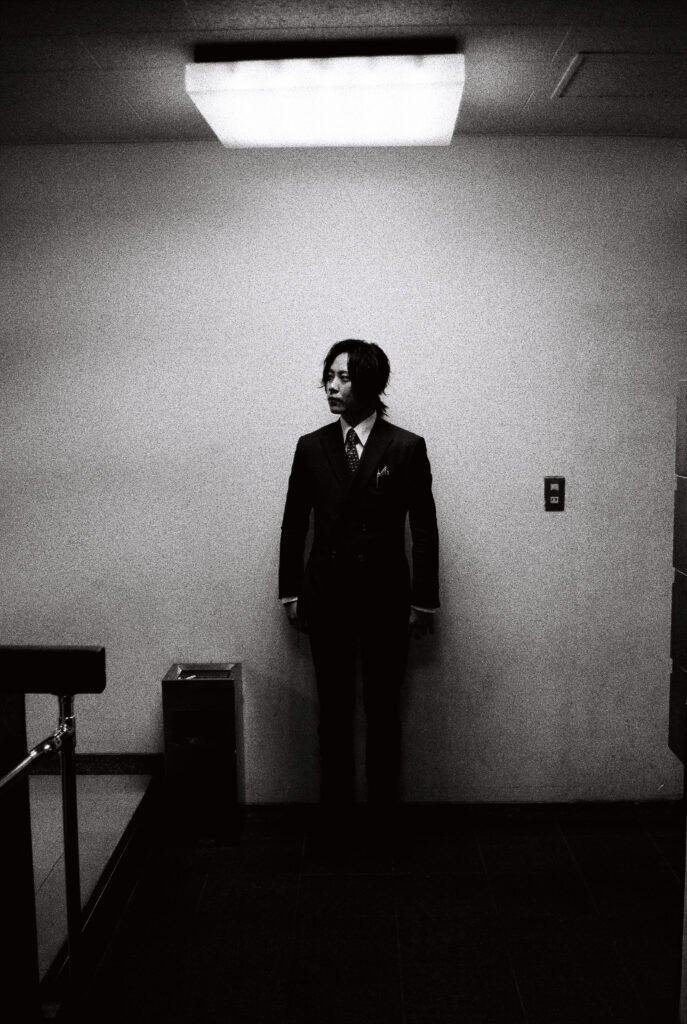

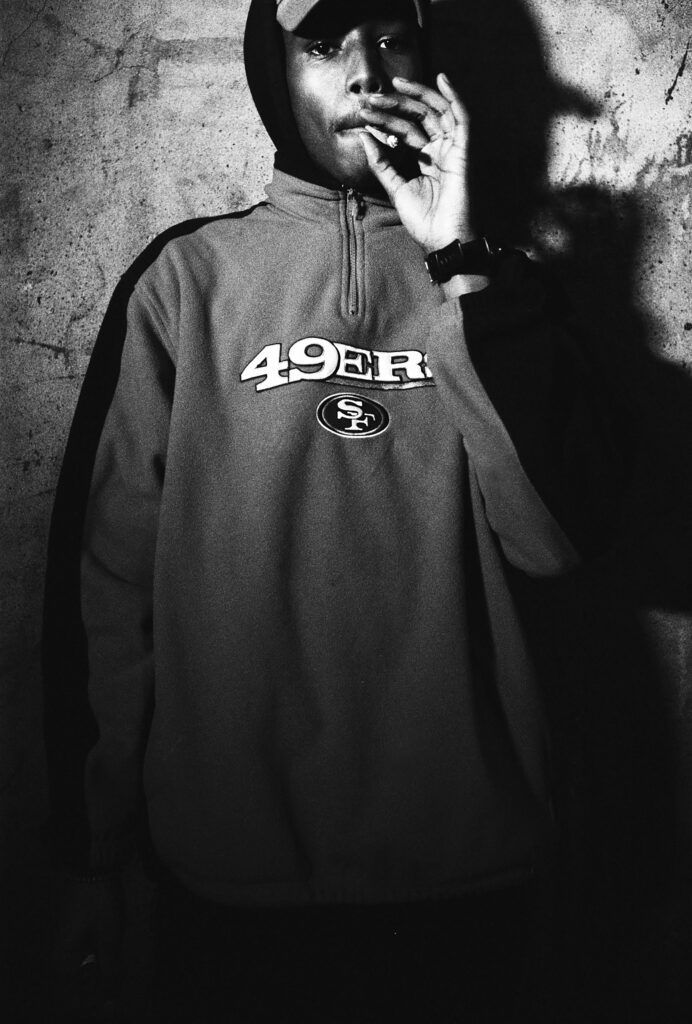

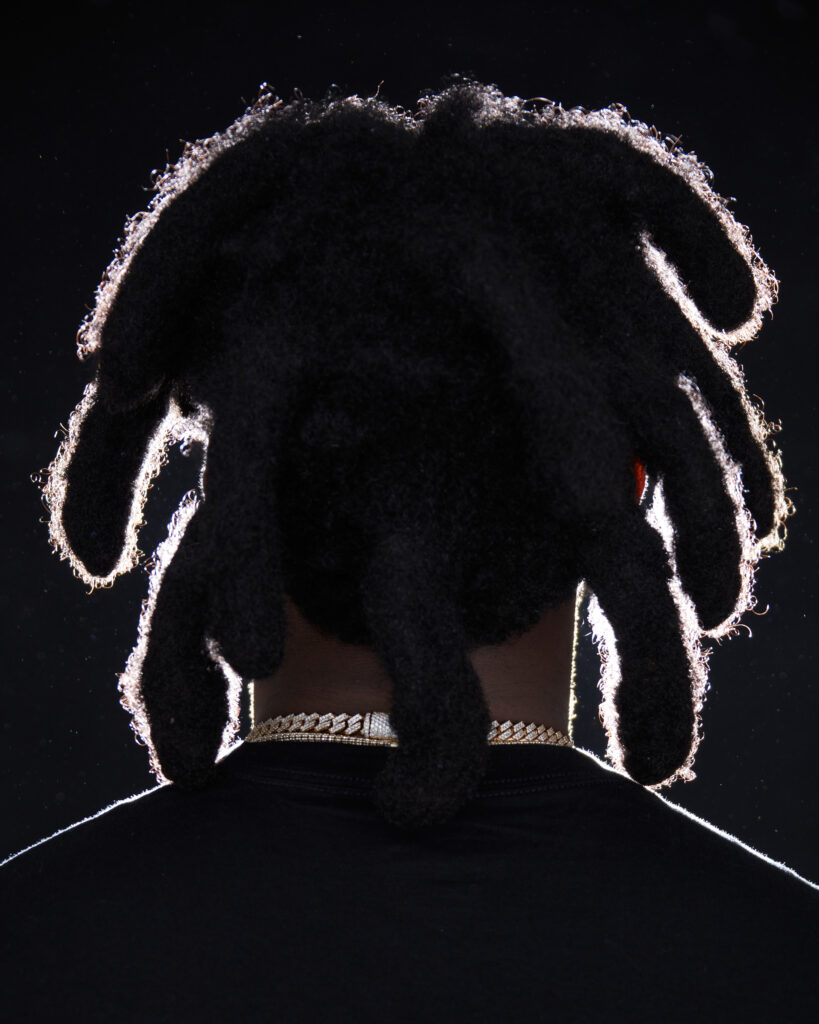

Louie Pastel and Felix, members of Paris Texas, take this call from their respective driver’s seats parked somewhere in Los Angeles. The sounds of the road muffle their voices and we leave our cameras off so instead I stare at circles – Felix appears as a grizzled Michael Jackson and Louie’s as the Mekhi Phifer Smoking Reaction meme, his name appearing as “That Guy”. Felix comments on the persisting gloom, a never-before setting in the City of Angels they call home. But as is often the case for Louie and Felix, there is something more to glean from circumstance. As if the gathered clouds were mirrors for the fires of this enduring retrograde, the smoke of cynicism, nihilism, all the -isms, burning holes in the things we hold dear. In this altered atmosphere, dystopia is rendered a collective emotion, we define “connection” by the amount of bars we have versus the feeling of having someone walk you home. Felix and Louie absorb this energy, observe the shifts and translate them into radical honesty reflective of the cultural climate today – can we run that back?

Paris Texas as a group, as a sound, is unbridled, an act of distortion perceived. Fans have likened them to delivering the unexpected, they’re “different” and hence, “refreshing” – unzipping musical genres while asking us to let go as part of the experience. As they gear up to release their full-length debut album Mid Air this August, they crank the steering wheels to the left, beckoning us towards the godforsaken – vulnerability, singularity, and self-awareness. Though the guys see themselves as “silly,” through the intersections they’ve built between sound and visuals, reality and delusion, id and ego, it becomes glaringly evident that they aren’t just on the map, but are making it.

Lindsey Okubo: I know you guys just released your debut album titled Mid Air and I was taken aback by the last two tracks, Ain’t No High and We Fall because they seemed to embody a new level of vulnerability lyrically. If Boy Anonymous was about y’all figuring things out and the mystery that comes with actualization, this one feels buoyant, sanguine and ultimately, assured..

Louie Pastel: Yeah I felt like two years ago when we really came out, it was like, damn, we got the attention on us really fast but the lyrics were kind of just fun and we weren’t really talking about anything. We tried here and there but we didn’t give people a lot. This time we gave people a little bit more and practiced the vulnerability part so our audience could get to know us.

Felix: We don’t always publicize our business. However, it was important to give people an update within the music. It’s a lot more therapeutic this way and there are different avenues for that but this one just feels better.

L: Right and I like the way you phrased it in calling it “the practice of vulnerability” too because it is something that you have to be cognizant of. What’s given you the courage to own your artistry more as you step away from relative obscurity?

F: We don’t take ourselves too seriously, we’re not pretentious but we can be meticulous in certain ways. Anonymity requires a way bigger team and series of events in order to execute it in a way that feels successful. We live in such a time now where everything is unveiled and people are finding things out all the time whether you want to call it research or not.

L: Yeah and tangentially, visuals have always been a huge part of what you guys do, allowing you to develop a whole other language and sensory medium to be understood through. There are elements of horror, nostalgia and surrealism that mirror this wave of escapist and nihilistic predispositions that our generation has been riding. Any thoughts?

L: Yeah it’s interesting because everybody’s kind of incentivised to be performative, especially in this online era, and we’ll get rewarded by this positivity most of the time. It’s really eerie, really dystopian and I see that and I’m like damn, if this changes in 20 years we’ll look back and ask, what the fuck was everybody on? I just try to give my perspective where I’m not pretending to be ultra-tough or extra flashy, I just want to paint a real picture of certain things. The first video, HEAVY METAL, was just us having fun and after that we wanted to show this parasocial relationship between men and women like we did in Girls Like Drugs. Men have this access into women’s lives so much and it’s in such a nasty way that we have a relationship with them. Guys be looking at girls all day, being actually horny about it. It’s like you don’t know this person, why are you sexualising them this much? We’re constantly watching and creating a fantasy in our heads that numbs us to any actual connection you can have which is why we depicted ourselves in the video as being behind the mirror or under the bed. We see her but she can’t see us. It’s doing shit like that instead of smiling, dancing and putting on a show for people.

F: It’s a satirical take on things for sure. Whether Louie comes up with an idea and I’ll piggyback off it, or we bounce things off each other, the ideas feel natural. It’s this weird, intuitive thing that happens because not every idea is always hyper-intentional in the moment. But when we start to refine it there are important messages that are revealed to us. Our subconscious has been holding onto what’s been going on us and it always just so happens to align with what’s been going on in the world around us. Even in these past few years I’ve seen a shift in how people were on top of self-care, on top of being conscious and aware and that was glamorised for a long time. Now you have people glamorising being depressed but also tying that to whatever their libido is on. The only stimulant or dopamine, if it’s not drugs and indicting yourself in that, are sexual pursuits.

We were in New York last week and that was a funny situation especially with the wildfire smoke and even in Los Angeles, it’s been gloomy for the past two weeks. This is the longest it’s been gloomy ever, with no rain, it’s just been cloudy. It’s interesting how that’s playing into our concept for the new project and is reflective of the climate of everything and how dystopic everything is becoming.

L: Yeah and you guys used the word “connection” and it’s ironic because in victimising oneself, people are often closing themselves off from attaining the very thing they want by claiming that. With music, obviously, it’s an emotional thing, there’s nonverbal nuance, lyrics as conversation, chords as language and I’m wondering how you guys define connection in and through your music? There’s also so many different styles of communication, what kind of communicators are you?

L: I think we’re really good at connecting sonically, me and Felix relate to each other so well. I don’t make music and worry about how it connects to people lyrically because we’re not that pretentious, we’re silly dudes. I think the way we present our shit to people is just inspiring people to keep pushing for something different. I don’t know if my story is that relatable to everybody and if you’re not an artist it is hard to relate to as well. Sonically and lyrically, I think it’s about pushing the weird shit, the different shit because the best thing you heard this week isn’t the best thing forever. Don’t stop, let’s keep going left with it. I want to keep connecting with people who want to keep going left as opposed to staying in a certain pocket.

L: Where does going left lead? To freedom from performativity?

L: I think it allows people to just think differently and I think that that’s the only way we can evolve as a people, is doing that. I think if they see two fun, silly guys keep doing the thing then people will know that it’s okay to think differently, it’s okay to move differently, and not in a performative weird way but the actual way. The more that people like us succeed, the more confident people will feel about not being so bland.

L: I feel like “difference” is ultimately about honesty and even with the name, Paris Texas, it’s about distorting perception and y’all are two Black kids who didn’t really feel like you belonged but found outlets that warranted connection. It’s an important reminder to have that ultimately connection isn’t just made but found. How much of where you guys are is due to that sense of lack – whether it was belonging or means and how present is an active sense of rebellion in your minds?

L: Like are we practicing being different? No, it’s something that already was and it’s not something I have to try to do, it’s what I am naturally. When I was younger, I had friends and family who conformed, were more straight and narrow and it worked for them, it’s not wrong but they thought getting me to conform would make my life easier but every time I tried, it just didn’t work. Going back to what we said earlier, I know there are a lot of people like me who are having a hard time and sometimes you just need somebody to show you how to move, you need to speak for those people.

L: Who are you guys speaking for? And for the straight narrow folks in our lives, how much of that is rooted in a sense of safety or stability and what driving force if any are those things in your lives?

F: A lot of the time it’s being able to follow the trail of your curiosity and having the space to think about things, that’s really what it is. No matter if you’re someone who is extremely fortunate or not, you’re trying to find ways to make it out of something. People are a lot more complex overall but they don’t always have the time to understand their identity or things about themselves that can benefit them and what they want to do. I think that’s what safety is really because it’s not necessarily relaxing but in having the time to entertain parts of yourself, you find out who you are.

L: It’s also about even being self-aware enough to want and need that time and space because life moves so fast and one of my biggest fears is waking up and being one day and being like, how the fuck did I get here? I feel like with the way things have happened for you guys, you understand these notions of speed, time and change which are such existentialist concepts and I’m wondering what your relationship to change is in general?

F: It’s just life bro, change is gonna happen. Hopefully you’ll be lucky enough to be like damn, I remember when it was so crazy. Everybody figures out a way to adapt one way or another.

L: You just live through the time and you can’t control it. What I struggle with too with change is that even when you want to change, you still can’t control it. It’s like saying I want to be this person tomorrow but you can’t control how that happens, you just roll with the punches.

L: Felix, I know you have especially talked about having faith in what you guys were doing and Louie, you had your like scumbag era and maybe that notion of having faith in something is maybe the only way to “control change”. Can you guys speak on self-doubt and on the flip side, what faith really looks and feels like?

F: I feel like it’s understanding that it’s just always going to be a thing. The mirror of yourself is constantly overlooking and overshadowing and you’re always going to think about what other people are gonna think. A lot of people say that it’s usually a good thing and it lets you know that you obviously really, really care. Faith and self-doubt complete each other because you’re only doubting yourself so hard because you want it to be so great, you love the process and you want it to be as good as possible.

L: Self-doubt and faith often get combined and they play with each other and become self-awareness at some point. I never have self-doubt really, it’s more so wondering where I’m going to fit into doing this thing and if people are gonna like it. You need the community, you can’t make music and be like, I’m the greatest. The community around you has to make you what you are so anything that would be considered self-doubt for me is just being realistic. I’ve never really doubted us at any point, I knew that shit can was going to be hard but it was gonna happen eventually. I never had impostor syndrome, I’ve just had this is where I belong type energy.

L: You guys were talking about those moments where you recognize yourselves in the music and moments where you don’t and therein lies this suspension of belief almost. I know sometimes artists see their artistry or practice as separate from who they are as individuals and I’m wondering where you guys draw the line?

F: When it comes to music it’s so weird because you always listen to yourself and you’re like, oh my god, that’s me, okay cool. The best moments are when you take a break from it and you’re like, I don’t know who that guy was that was on the song – and I know it’s me – but it’s like that was crazy. I don’t even care that it was me, it’s just like, oh shit.

L: I love making a song and it’s like dang, I’m listening to this as if I’m listening to one of my favorite artists.

F: Yeah like I’m listening as a listener. I don’t have the pressure of being like my voice sounded weird or the beat is fucked up here, it’s like like whoa, what an experience. [laughs]

L: If I make a song and I don’t feel like it’s me personally on there then my job is complete because I’m hearing it as a fan would hear it. Sometimes I’ll make a song where I’m like, oh, they’re gonna fuck with this because I fuck with this. I’m listening to it like, oh who the fuck is this? It doesn’t feel like government name, grew up here, did this, it feels like who is this guy? I’m a fan of him.

L: Yeah and these notions of legacy are also tied to music where you have this ability to live on far beyond your time or after you’re gone. What is your relationship to the word legacy?

L: It depends, legacy is cool but I’m not a legacy guy, I don’t even want kids. It’s what the people decide to do with it but to have an impact on one person’s life is enough. I’ve had bands that no one’s ever heard of before in their life, 10,000 views dropped the song in like fucking 2006 but I still love them and they have an impact on me. If one person who is not a friend or someone you’re related to is like, I fuck with this thing, that’s so importantIt’s a crazy thing to make something and somebody is like I resonate with that. People take legacy as a means of saying your impact was huge but that’s some industry shit, it’s a game you have to play.

F: We’ll see man, it won’t matter, I mean it will matter but we’ll just see what happens.

L: Also thinking about the nuances between pop culture versus art. With pop-culture you’re measuring impact with virality and inferring that it equates to emotional resonance or understanding but I think there’s a difference between those things. In pop-culture, the message often exists in a watered down version of itself, it’s digestible to the masses and with music or art, you have an opportunity to create something truly singular.

L: Yeah for sure, it’s a whole different thing. Pop culture is interesting, we need it but I think a lot of people don’t want to invest the time to connect with their feelings. I remember this one person I was talking to told me that she wasn’t a fan of music, which was crazy to hear. There is a majority of people who are not fans of shit. Meanwhile, we like all these weird little things and can argue all day about them. Even the question of pop culture versus art, the average person doesn’t really care. They’re like, does it make me want to dance for five seconds? They don’t even care if the creator disappears, being popular is a matter of the now, looking kid and if the kids like it? Fuck it. Pop culture can just go away. Like Picasso isn’t pop culture, people who make art aren’t pop culture. He’s popular, but he’s not pop culture.

L: Yeah everyone’s lost in the sauce. Do you guys believe in true love?

L: It’s funny, I think sometimes people think that true love is from person to person but I don’t think it’s black and white as that, sometimes you can love something and you truly love it, it could be art, a hobby, a smell. I believe in it, truly.

F: It’s almost like a nirvana state in a sense, there are just so many ways to go about it. Love in itself, a lot of people see it as a limitation but it’s a word that can contain so much more than what it is that it becomes malleable but somehow we’ve reverted it down to a shape.

Team

Photography · Lindsay Ellary

Styling · Shaojun Chen

Grooming · Arlen Jeremy Farmer

FX · Emily Taylor Hirsch

Special thanks to Orienteer

When Joshua Gordon went to Thailand, he followed a gang of teenage bikers and witnessed their fraternity. He saw how the young boys had each other’s backs and would die for one another. He directed the film about this along with the country’s occultism and witchcraft culture that religious people might completely exile in their belief systems, but that other people base their spirituality and faith on. After a while, he wanted to investigate the drag landscape in Cuba. Armed with his lens, he was hoping to capture the tight-knit drag community in a country that might not yet be open to the queer scene. He ended up meeting twin trans sisters and peered into their intimate life.

Joshua’s thirst for fascination also brought him to Japan. Amidst the psychedelic allure and eccentricity of the country, he photographed the locals’ fascination with toys. He saw young punks living and sleeping with their plushies, a lifelike woman giving birth with the baby’s head popping out of her vagina, and lots of latex sex dolls in stores and homes. Somehow, Joshua knows how to excavate the surface of the social infrastructure. He digs hard and deep that midway, his photographs and documentaries have unraveled parts of him that seem to be hidden in plain sight. These visual cues are snippets of the ups and downs he has gone through in life and art, a narrow gateway to who he is and how he became what he is.

Take ‘Transformation,’ where he manipulates photos of himself using artificial intelligence to bring about different versions of himself. He considers the project special to him, but viewers seem to have only noticed and commented about his physique and the size of his penis. The series has become reduced to a visual commodity for public viewing, making Joshua aware and alert to the current relationship between art and the viewers. What Joshua creates gives nothing in-between; either the viewer gets startled by the brashness of his images and films, or they feel for the emotions the visual works evoke. Every publication and project hides a backstory, and in a conversation with NR, Joshua brings them to light.

Matthew Burgos: How did you develop your documentary style in photography, video, and collage? Has this always been your intended style?

Joshua Gordon: Documenting was always the first thing I did. I started using photos as a tool when I began creating pictures at around 13/14 years old, not for any artistic reason or self-expression. Every skate crew needed a filmer and/or photographer, so that’s what I became. And every graffiti crew needed someone with a camera, so I filled that role too. Over time, through graffiti, I learned more about photography and discovered my favorite photographers. After that, I delved more into what might be considered quite traditional documentary photography.

Matthew Burgos: Let’s discuss your zines Diary Part 1 and 1.5 which definitely have the documentary photography style you just mentioned. Do you see the photos in these zines as a reflection of how you saw and painted the world at the time, with the use of dark and gritty imagery?

Joshua Gordon: I think it’s dark and gritty because I was depressed and poor at the time. I was living hand to mouth and didn’t really have a penny to my name. When Diary Part 1 was made, I was working in a warehouse loading trucks and stealing stuff from high-end stores for cash. The other zine was created just after I left.

I think that when I started making pictures for those books, I wanted to shock and be brash. I was surrounded by a lot of misery, staying in moldy bedsits with rats crawling on my ceiling, and I was never able to pay my rent. Shocking isn’t my intention now; I’m more interested in evoking emotions.

Matthew Burgos: Your Butterfly project seems to have a similar style yet a different tone. Can you talk about how you approached this project, and what brought you to explore the nightlife in Havana?

Joshua Gordon: Well, I don’t really plan much; I just go with the flow and feel things out. I’ve always been inspired by 80’s drag, and it’s been a constant source of inspiration for me. I wanted to find some older drag queens and live with them.

Aries offered me the chance to go to Cuba and work on a project of my choice, including creating a book. I was going there to explore and see what I could find. When we arrived, the queer world was small and super intertwined. It ended up being less about drag and more about these two twin sisters I met and their friends. I suppose you could say it was a portrait of them and their community.

Matthew Burgos: You also directed Krahang, following a group of teenage biker gang in Thailand. How did you discover them, and what did you learn about them that wasn’t evident in the film?

Joshua Gordon: There are a lot of interesting things happening in Thailand—hidden customs and alternative perceptions towards topics that might be considered taboo in other parts of the world. What sticks out to me when I spend time in Southeast Asia is the sense of community. The West is obsessed with individualism. Everyone thinks that the world revolves around them and people have the “main character syndrome.” There’s no decency or love among people.

In Thailand, life is hard and fast and vibrant. There’s a strong community spirit. The boys in the gang were best friends and would have died for each other. I was also very interested in Thai witchcraft and occultism, which is something pretty much everyone there is interested in or scared of. I touched on that in the film along with the teen biker gang.

Matthew Burgos: Let’s talk about your investigation into adult toy culture in Japan leading to the book TOY. What specifically drew you to explore this topic in a country known for its eccentric culture?

Joshua Gordon: I love toys; they’ve been important to me my whole life. Objects bring me a sense of comfort and fluffy familiarity when I travel. Everything in Japan is “kawaii:” you see an ambulance speeding down the street and its logo is a smiling drop of blood. Even the police logo Pipo-kun is fucking adorable. Japan is cute but it also has a dark edge. I wanted to show that mix in the book; the duality of cuteness and darkness.

During my time in the Japanese countryside, in a quaint area called Gunma, I found an old toy museum. Inside, I discovered these porcelain sculptures of couples with long robes on. When you turn them upside down, you see the characters’ penises and vaginas with fuzzy pubic hair. A lot of things in Tokyo have a hidden meaning or a secret backside; I wanted to explore that.

Matthew Burgos: How about ‘Transformation’? Is it a visual anthology of the growth you’ve experienced throughout your career?

Joshua Gordon: I was at my lowest when making ‘Transformation.’ I was dealing with a severe eating disorder, hospitalization due to tumors, a difficult breakup, and substance abuse, and I felt like I was going insane on a little beach in Mexico. The photos helped me escape somewhere else. I tried to use artificial intelligence and children’s image manipulation apps to create a fantasy land of my own.

But nobody understood. I received comments about my physique and penis size—just basic interpretations of something that meant a lot to me, a project that acted as sort of a ladder to help me out of my hole. It was devastating. I spent around 7,000 pounds and six months creating the books and artworks. I managed to sell only one book at the exhibition and not a single painting. It was quite upsetting, but the project (still) means a lot to me.

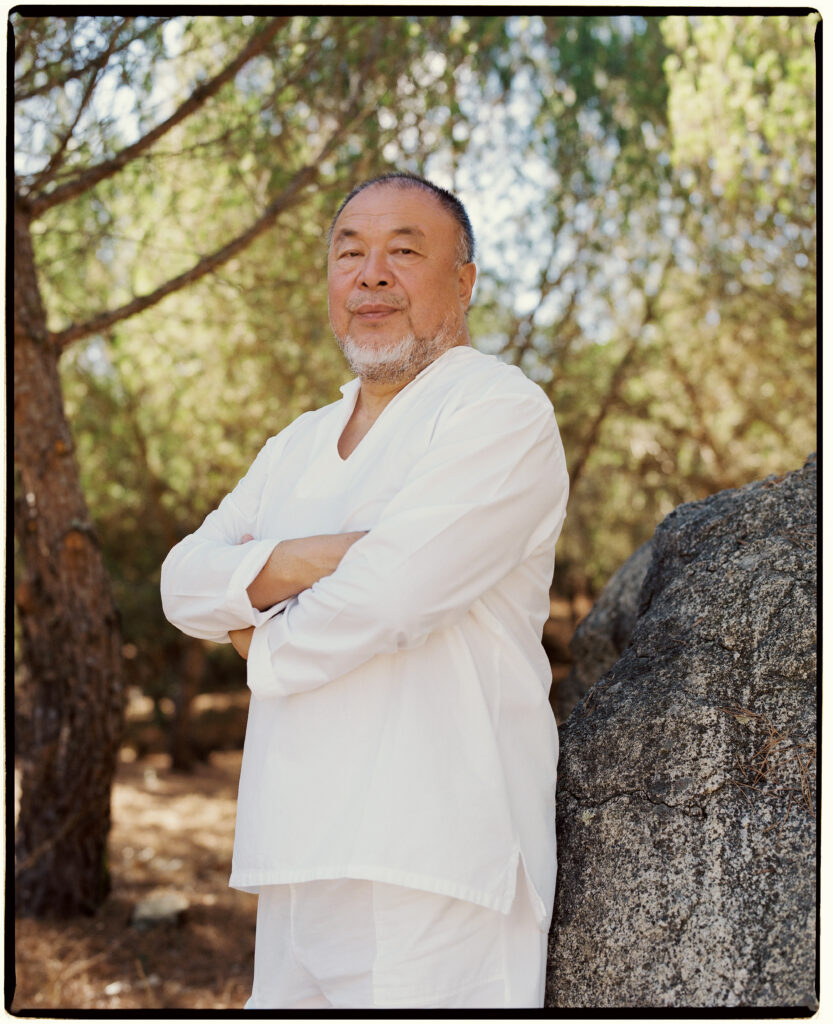

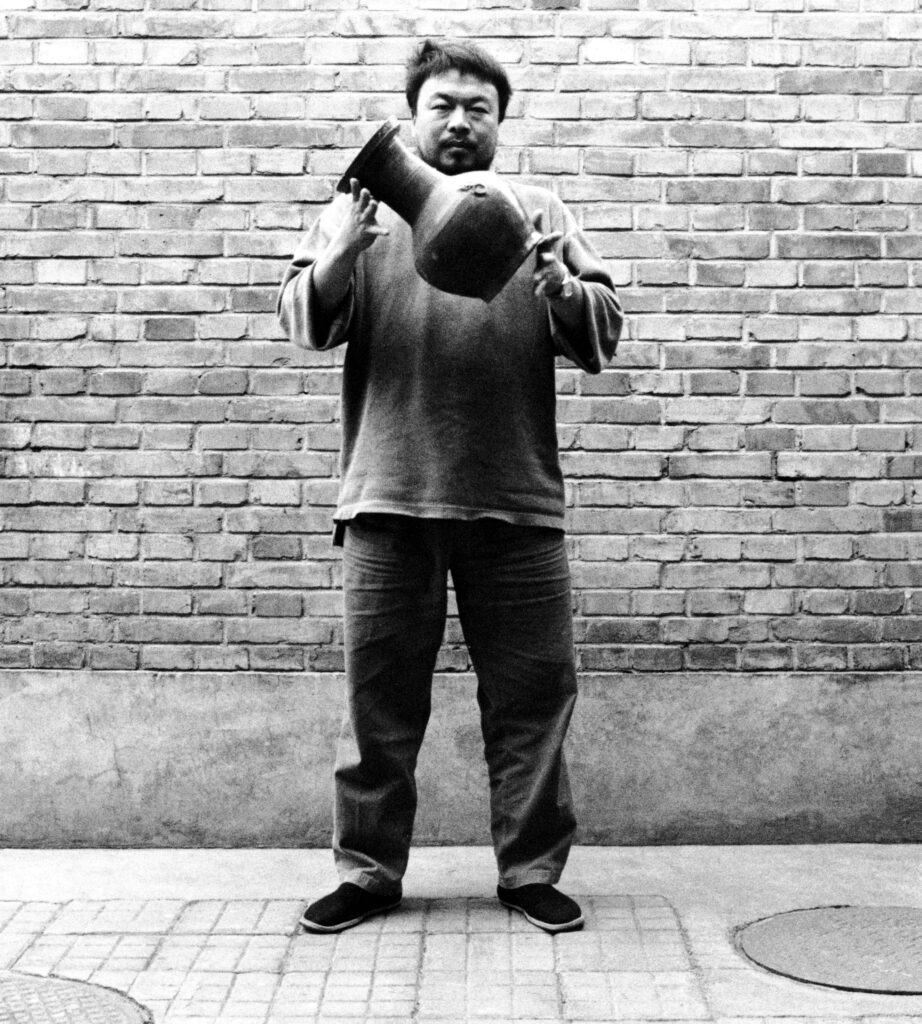

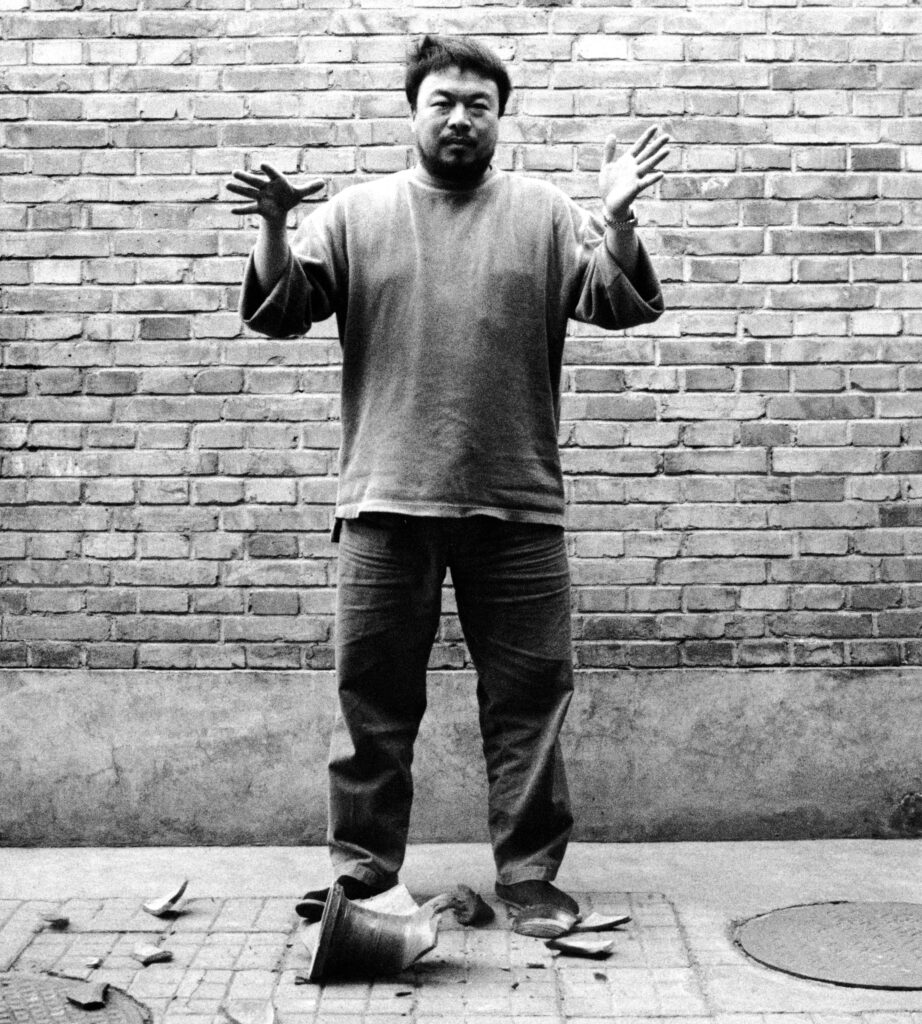

Ai Weiwei (b. 1957, Beijing) is undoubtedly one of the most influential and fearless voices of our time. In a world where the right to express oneself is often taken for granted, Ai Weiwei’s unwavering commitment to this cause emerges as a clarion call to create inclusive spaces where every voice is respected and cherished. “Expressing oneself is a part of being human. To be deprived of a voice is to be told you are not a participant in society; ultimately it is a denial of humanity”. A statement followed through by the immense outspoken nature of what Ai Weiwei’s body of work testifies to be. As he beautifully puts it in this interview, without free expression, we lose our expressive uniqueness, “akin to flowers that fail to bloom, birds that cannot soar, fish that cease to swim, and clouds that no longer drift across the sky.” Ai Weiwei’s art transcends mediums, seamlessly merging with activism in works like Remembering (2008) and Human Flow (2017) where he sheds light on the plight of refugees, compelling us to take action and empathize with those in dire need.

His exploration of cultural heritage, craftsmanship, and the value of everyday objects in his latest exhibition at the Design Museum in London serves as a testament to his enduring commitment to preserving our shared history. Our conversation with Ai Weiwei also delves into his relationship with technology and social media, illuminating the complexities of online engagement in a world marked by censorship and rapid change. He offers his perspective on the evolving role of design in contemporary society and reflects on his deeply personal connection to the objects he collects.

In this interview, Ai Weiwei also delves into how his journey with his father, Ai Qing, not only shaped the man he became but also paved the way for the unique connection he shares with his son. Standing at a crossroads of generational wisdom and personal growth within the complexities of parenthood, identity and the world he envisions for the next generation, Ai Weiwei finds himself tasked with the delicate balance of imparting the lessons of his past without allowing them to cast a shadow on his son’s future.

Ai Weiwei shares not only his artistic vision but also his unwavering commitment to the values of human rights, freedom of expression, and the enduring power of art as a force for change.

Jade Removille: Ai Weiwei, it is a pleasure to be able to have you as part of this upcoming issue. Where are you now?

Ai Weiwei: I am in London at the moment, but my residence is in Portugal.

Jade Removille: On your website’s homepage, the powerful statement “Expressing oneself is a part of being human. To be deprived of a voice is to be told you are not a participant in society; ultimately it is a denial of humanity”, urges society to create inclusive spaces where everyone’s voice is respected and honoured, reinforcing the notion that self-expression is not just a privilege but an essential aspect of our shared humanity. As an outspoken dissident artist and a fervent activist for human rights, could you delve into how significant self-expression is to you?

Ai Weiwei: Thank you for your insightful interview question and for taking note of my comment on free expression. Free expression is often perceived as a core element of human rights. In a deeper sense, without free expression, each individual loses their unique attribute that belongs to them. If such circumstances prevail, our society would be robbed of its expressive features, akin to flowers that fail to bloom, birds that cannot soar, fish that cease to swim, and clouds that no longer drift across the sky. Such a world is indeed a daunting prospect.

Free expression facilitates our ability to perceive the world as an extension of our senses and emotions, enabling the manifestation of our unique perspectives. It is through this individualized articulation that we can truly appreciate the richness of human nature and the value of our shared humanity.

In my view, free expression is not exclusive to artists or to those who construct foundational thinking paradigms. Rather, it is the most crucial element that defines us as human beings. Stripping away the right to free expression is perhaps the most damaging action against individuals, as it strips away their very essence.

Jade Removille: Has your sense of belonging to China been undermined since your exile in 2015? Have you found your oasis of peace? Do you see a future in which you would come back?

Ai Weiwei: My sanctuary of serenity resides solely within my heart. Much like a diligent gardener, I continually tend to my personal thoughts and expressions, nurturing them so they can flourish. It would be accurate to describe me as a person without a homeland. From my birth, my father was deemed an enemy of the state, so I grew up in exile within my own country during my early years.

Subsequently, I embarked on a journey abroad, having lived in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Portugal. None of these places can be referred to as my hometown. My maternal language is Mandarin Chinese, which makes my existence in these foreign lands akin to navigating life with a disability, relying heavily on body language and gestures to barely communicate. Nevertheless, I am profoundly grateful to these countries for providing me with opportunities to engage with issues that matter to me and to remain active.

Jade Removille: At 15 years of age I was introduced to your work through the Sunflower Seeds installation in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern (Kui Hua Zi, 2008), and it left a lasting impression on me. I remember my parents and I were utterly amazed by the meticulous craftsmanship of the seeds, their delicate nature, and the sheer scale of the installation, which was difficult to fathom. In an interview for Tate, you mentioned that sunflowers symbolised the revolution, providing both spiritual and material support for the people. The immense quantity of seeds created for Tate Modern was unimaginable, yet you accomplished it. Witnessing such a meaningful installation also benefiting and providing employment for the hundreds of artisans involved was truly moving. Could you talk more about this work? Did you plan on the installation to interact in a specific way with the location and the visitors?

Ai Weiwei: Thank you for sharing your experience of encountering this artwork as a teenager. I must confess that I also first saw this installation in its entirety at Tate Modern. At that moment, my feeling was the same as yours.

When an artist embarks on creating an artwork, it begins merely as a concept. The particular characteristics of this concept were its grand scale and voluminous nature. What is more important is that these 100 million sunflowers were each meticulously painted by hand by 1,600 women. These women, dedicating two weeks of their lives to this project, rendered it almost a religious activity of a kind of daily expression. The sunflower seeds are the embodiment of their craftsmanship.

In Jingdezhen, the town of these women, this is their tradition as well as a means of survival. Concurrently, their straightforward task of painting sunflower seeds encompassed a profound sense of interest and engagement. This imbued me with a feeling of the enduring power of art. It doesn’t simply draw people’s attention, but its creation is also a testament to the investment of time, the grandeur of volume, and the concerted labor of many hands.

Jade Removille: I would like to address your practice as an architect. You used to run FAKE Design with which you realised 60 projects. FAKE closed down shortly after the Olympic ceremony for which you had designed the Bird’s Nest’s stadium in collaboration with Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron. Your involvement in this project helped to shape its iconic and innovative structure. You brought to architecture, the humanity it needed but you have mentioned before that you had had enough of it. Why does this medium not suit you anymore?

What was your very first architecture project?