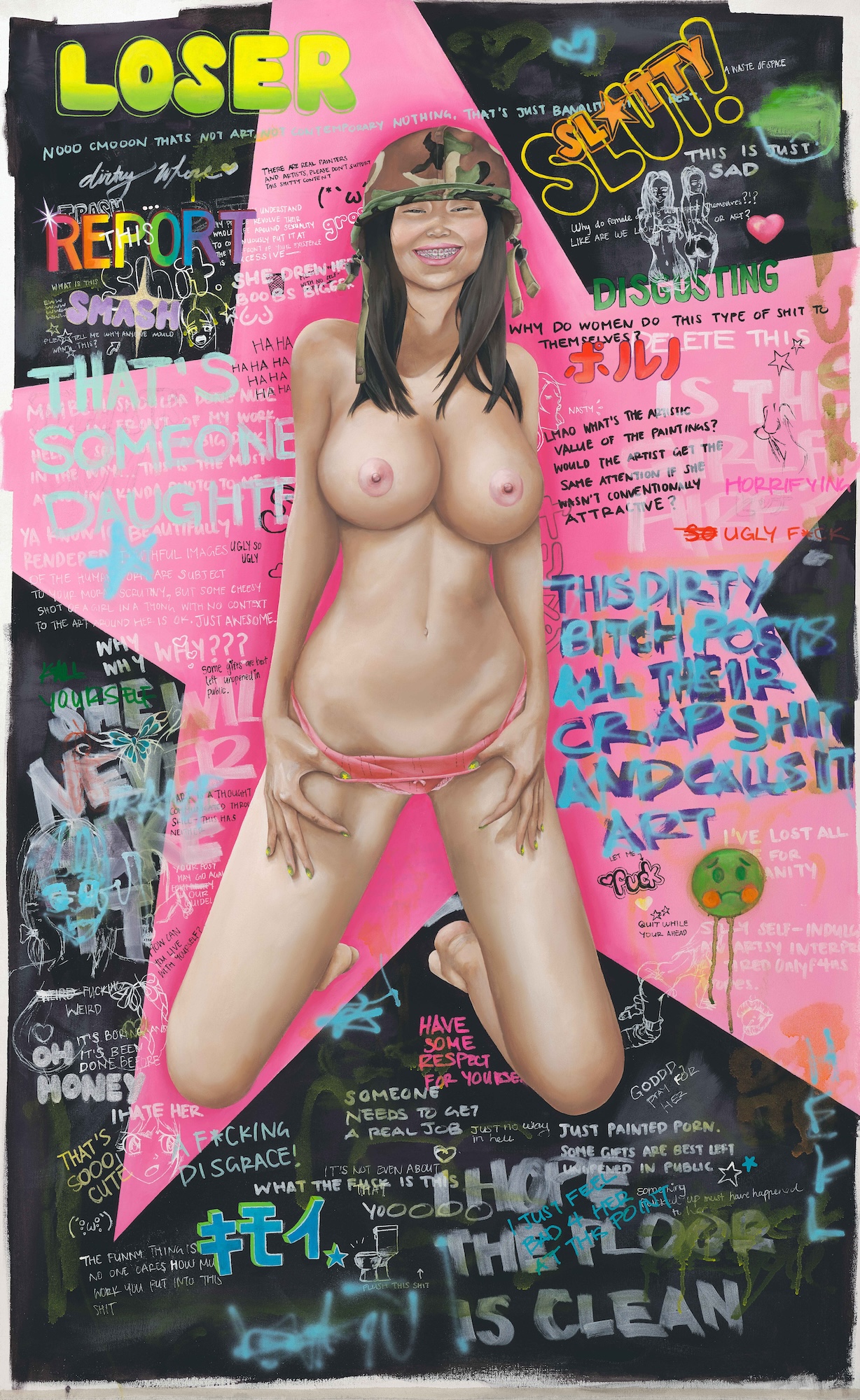

Jasper Johns once said, ‘Hollywood is forever young, forever sexy and forever swollen with abundance.’ This makes sense when looking at the figures in Kate Ahn’s paintings.

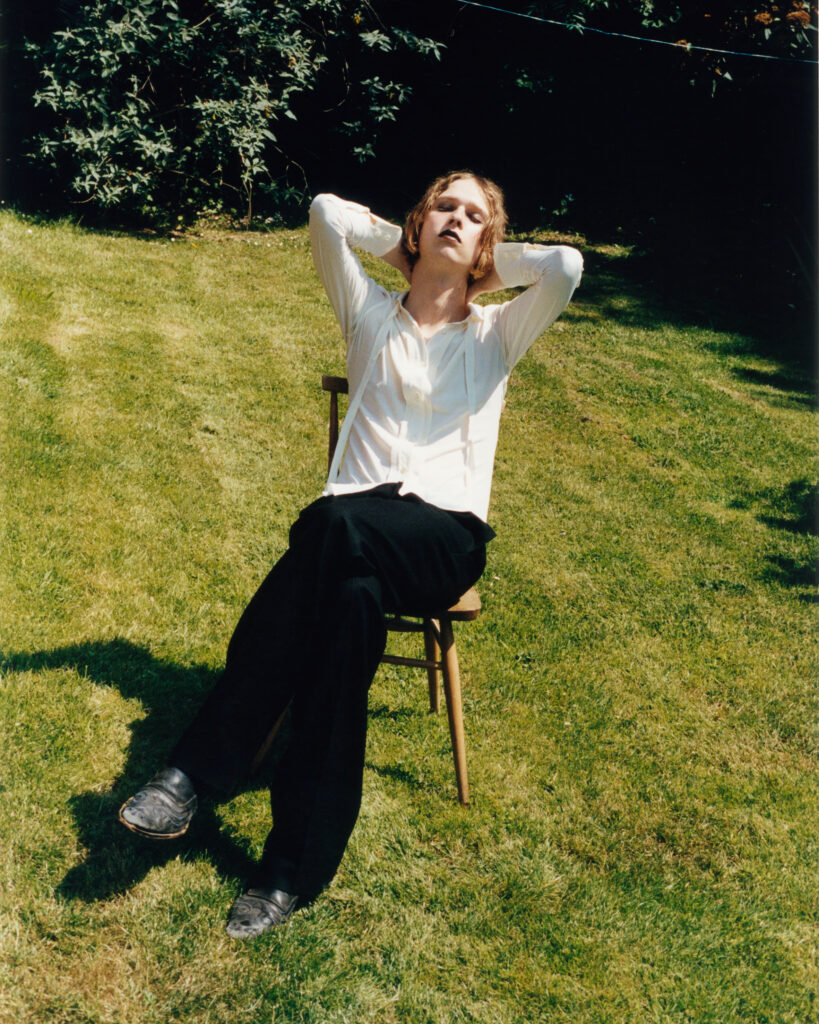

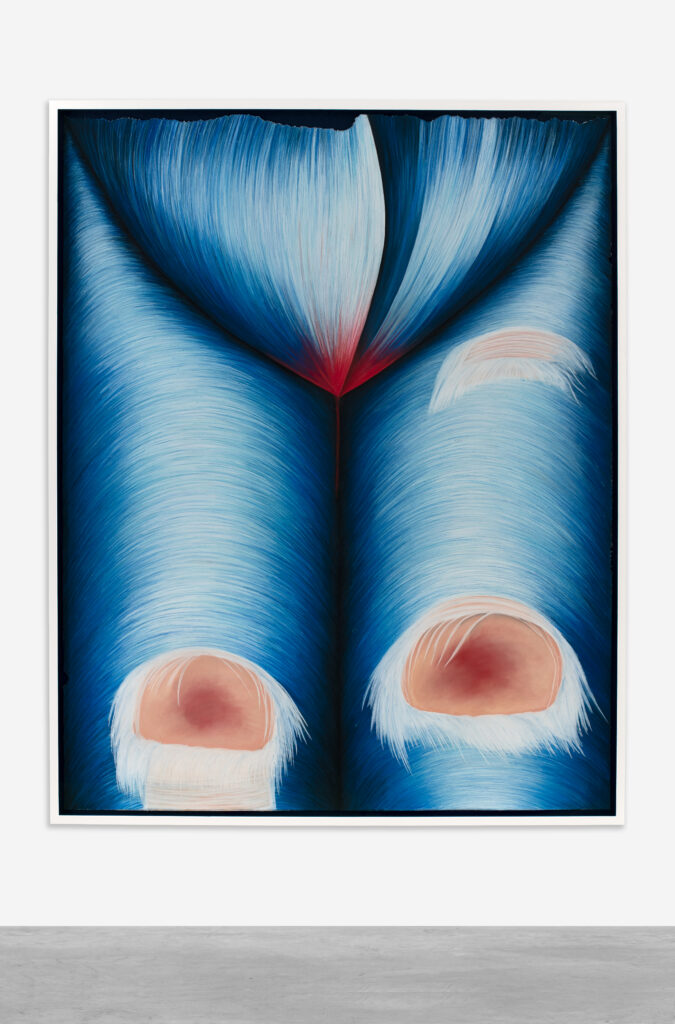

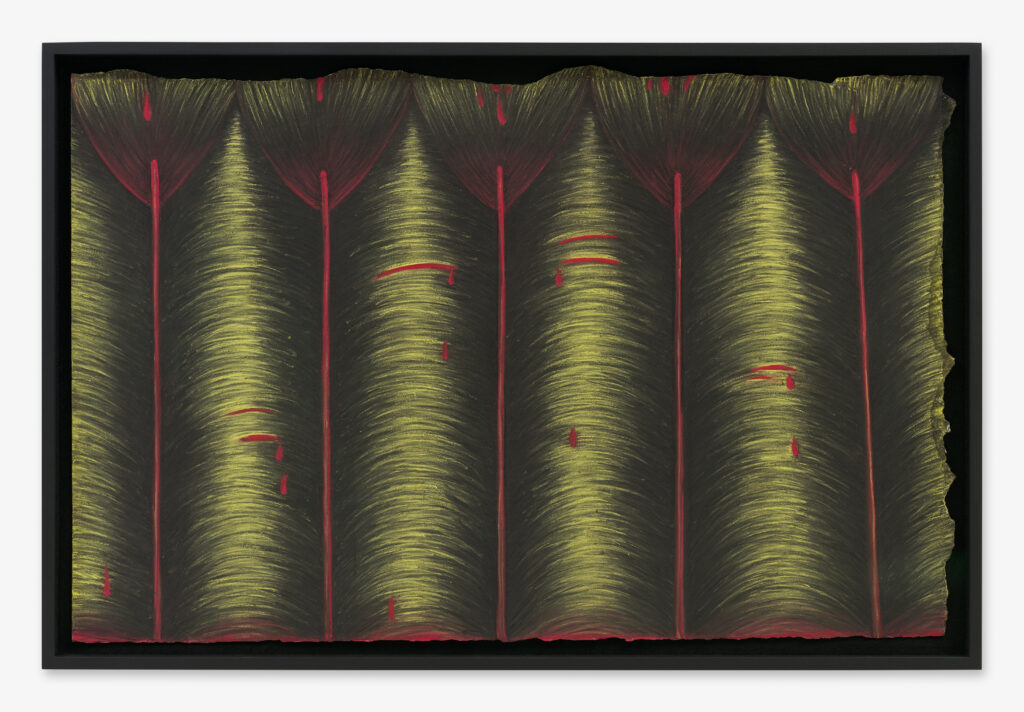

However, abundance in these works is qualified by searing faces and billowing forms stretching across the image and twisting in the frame. They are abundant in mixed yet meaningful messages, pained and charmed. Painting in series, Ahn depicts herself in varying stages of movement. Nearly always nude. The relevance of this nudity is open to interpretation. Still, Ahn’s subjects bring to life the late critic John Berger’s words, ‘Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display. The nude is condemned to never being naked. Nudity is a form of dress.’

These figures are not just nude but clothed in meaning. They are overcorrections, pronounced perfectionism with an outcome of exaggerated beauty. A swagger of confidence sways on a bed, bounding between big buttcheeks and long legs, wavering between buoyant breasts and the torrential currents of bedsheet and brick wall. These forms are idealisations, idylls of what could be. They are powerful, exposed, fearless, and nuanced in nakedness, fiercely facing everything with glowing skin and stripy socks.

Ahn is in Los Angeles. She grew up on the United States West Coast and has lived there for most of her life. In recent times, Ahn’s paintings have developed an ethereal strength. She discusses her work and artistic intentions are spread across the social and physical dermis of expressive geography. Ahn’s world is mapped around acrylic paint and produces figures that produce shock therapy that will force any white wall into submission. And they are also nude, but that’s only half the story.

Billy De Luca: You are in LA right now. Did you just have a show there?

Kate Ahn: I had a show downtown at Gallerie Murphy — it’s an extension gallery of Terminal 27 on Beverly Blvd — and they just opened. I was there for one month, which was a great experience. It was very emotional for me because I sacrificed a lot for this show. It was almost 2 years of work, it was everything I had in me.

Billy De Luca: The commercial gallery scene can be terrifying. But having that proximity in LA must have been great. Did it get overwhelming having such access to your exhibited works?

Kate Ahn: Oh, no, I was even there after the opening a few times. I was so much a part of everything. From the paintings to the merchandise with Terminal27 and just the gallery preparation itself, I was there at every step.

Sometimes it is hard to collaborate and find people to take up your vision, but when there is synergy and trust, things always turn out beautifully. I also enjoyed being in the gallery to say hi to whoever came by.

Billy De Luca: That can be a very personal experience. It changes the context when you see the person who painted the image before you. And how come you liked the collaborative aspect?

Kate Ahn: I like it, but I also think it can be challenging and sometimes divisive. I feel like I am also thinking about the audience and what the general public can digest each time I collaborate. As an artist, when you create your work, you can really just go all in. I don’t think about whether everyone will love it, but you have to consider that in collaborations.

Having that restriction is also nice because It makes you think outside the box. You have to please other people and yourself; it allows me to have my art in many mediums. It isn’t just up on a wall: It can travel and transform into many different objects and forms, which is super exciting too. I try to do as much as possible within my freedom, but sometimes you can’t go completely explicit – for example, on a pair of shoes.

Billy De Luca: Finding that balance must have taken time. When did you start painting and getting into the fashion side of the arts? Did the transition help with selling your ‘ideas’ to the world?

Kate Ahn: I’ve been painting since I was 6, but I’ve also been into fashion since I was in my mother’s womb. A lot of it came from her. She’s always loved fashion and the arts and was the first person to introduce me to these worlds. From the outside, we are like complete opposites. But actually, I’d say there are more similarities than differences. I have this feeling that my mother sees me as a reflection of herself. Deep down, she’s secretly cheering me on and healing her inner child through me – even though she’ll NEVER admit to that haha. It’s like she’s looking at a mirror to see what she could’ve been (if all the rules and societal pressures didn’t alter or make her afraid of what she really wanted to do). I think I am my mother, and she is me.

But back to fashion haha. She definitely appreciates the design and artistic aspects of fashion, but I think she, just like many other people, is also attracted to the idea of class status that is prevalent in that world. This is where I’d like to think we differ: I love the art of fashion, but sometimes it can feel a little like high school. Personally, I don’t care about what’s most popular this season, who’s seated where, and what somebody is wearing at a show. Although I understand the allure, I just enjoy what makes me feel good based on my own narrative and understanding of each piece.

Fashion has done a lot for me. It has helped me deal with the insecurities I’ve had my whole life, but it also gave me the freedom that I felt like I didn’t have. Clothing and accessories were my costumes and a mask. I wore it like armour.

Billy De Luca: That’s the beauty of being an artist, don’t you think? Fashion is in that same weird middle ground. It’s like hair. It will grow out of you and can get long enough to be another limb and part of who you are. But sometimes, it can get knotty and be a pain.

Kate Ahn: For sure. I definitely turned to painting to create these fantasies since I had such poor self-esteem (and still struggle with it). It’s how I cope to get through all of life’s bullshit. I think that’s how it is for a lot of artists. We are all struggling and trying to figure it all out.

Billy De Luca: Do you always paint yourself?

Kate Ahn: I have since I was 6. I remember one of my first paintings of a beach filled with all these girls, and all those girls were me. I’m not kidding. There were like 20 versions of me on that beach. But even since then, I’ve always encountered these “teachers” that did not seem to fuck with my vision! When I went to a bunch of art classes (a lot of them were Korean art classes), I had a couple of teachers who were very chill and open-minded, but I also had many teachers who were very conservative. One didn’t even offer figure drawing classes because it was ‘inappropriate’. I thought that was so crazy.

Billy De Luca: Where was this?

Kate Ahn: I grew up in Irvine — It’s a really nice area. You know, the suburbs. It’s deemed the safest city in America, with a huge Korean community. But I always hated it. I can’t think of a time when I didn’t want to leave. I feel privileged to be brought up in such a safe environment, but the environment felt so stale and mundane. One of the art classes I attended was 20 minutes away from my hometown, but the guy who ran the place was horrible. I eventually found another class that meshed better, but as much as I wanted to paint what I paint now, due to my age and environment, it really wasn’t an option. So I focused more on objects and foods that represented the female body and sexuality at the time. It wasn’t until after college that I got to my self-portraits.

Billy De Luca: Why was that? Where was college?

Kate Ahn: I didn’t attempt to do my self-portraits until after college. The love that I got from my parents (after getting accepted into USC) felt too good to stray away from, especially after so many years of rebelling during my tween and teen years. So, naturally, during that time, I gave into their ways — which meant giving up art as a career. I went to school and went from art to Communication (with a minor in Finance). I told my parents — and convinced myself — that I would go into banking and make a lot of money. I thought that after that, someday I’d get back to my art…But that didn’t happen. I never did any of that besides graduating, but that’s something, right?

I tried my best to conform, but it was just not in me. After my second year, I realised I was never going to be the person they wanted me to be, and I didn’t want it either. After graduating in 2020, I painted my first self-portrait. After my various jobs, I saved a bunch of money and said, OK, let me do what I want … I bought my first HUGE canvas. It had been my dream since I was 14 to paint on a canvas like that and to have enough time to work on such a scale. I was still shy and didn’t show my face. I marked it off. But the bodies remained. They were all me, variations of me or dreams of what it could look like. It became a fantasy.

So yeah, that was my first self-portrait, and it sold, so I thought, ‘I must be doing something right!

Billy De Luca: And how did your parents feel about that?

Kate Ahn: They are still upset. I can sympathise with how they feel. As conservative parents, I think the subject matter alone would be difficult for them to digest. But on top of that, there is also a very real fear of their only child not having the stability that a more traditional career choice can provide. It’s not easy selling pieces, for sure. But that first piece was definitely something I took as a sign to just go for it.

Billy De Luca: Do you think that painting is easier than the administrative and sales aspect?

Kate Ahn: Painting is way easier. It would be a dream to just paint and not worry about the selling side of the job haha. It makes me depressed sometimes, and it can feel like things are predestined in this industry. It’s so much about who you know. I ask myself a lot: Are these the things that make or break me as an artist? Do I need to be a person that can talk up my work or have someone willing to do that for me? Yes, it’s discouraging. But in the end, I can’t see myself doing anything else. I can’t stop what I’m doing, and I believe that if you really love it, you’ll find a way.

Billy De Luca: Beforehand it was very much about the quality of the work and the consistency it bore in improving over time and being relevant in such times. Now, it is about self-marketing. You can have an agent and a Gallery, but if you don’t have a personality, then you can sell paintings all you want — but you may not be memorable. With your work, the images strike and transfer energy. Audiences have received that energy and are buying in. You can sell a painting, but you have to sell a self-portrait.

Kate Ahn: Yeah, I agree. Social media has definitely inflated and put this importance on not just your work but a person being an entire package. It’s like people themselves have become conglomerates: you’re the actor, the producer, the director, etc. Everyone has to become a multi-disciplined brand that must follow the fickle nature of social media. Like a walking billboard. It’s overwhelming, but it can be great because you can get your work out independently, cutting out the middleman like agents or galleries. But at the same time, there’s a negative side that comes with oversaturating the avenues that lead people to not take you as seriously. I think of Andy Warhol, who essentially went for it and did it all. And unfortunately, having to deal with silly repercussions where some circles of the art world stopped taking him seriously for doing things unconventionally at the time. Fast forward to now, it’s kind of ironic how his way of doing things ended up becoming the standard today. Even now, it’s still hard to navigate what the perfect balance is between doing it all and still being taken seriously.

And man, there are so many days where I have wished I could paint anything else. Any object, like food or something. It’s easier to sell that as an idea. Instead, I paint really explicit self-portraits. And on that, there is a double standard. Women are in this really unjust and tough position where we are constantly objectified living in this patriarchal world, but the moment we start owning our own sexuality and our own bodies, we become lepers. As much as my work receives a lot of love, it also receives so much hate. Even though we’ve been painting nude women for centuries, I think it is still very new for women themselves to be the ones painting our own bodies. I guess that’s too progressive even for this world haha.

Billy De Luca: And what does that mean to you?

Kate Ahn: That’s one of the very reasons I continue to paint my self-portraits in the nude.I am fighting for my right and everyone’s right to own our sexuality and our body and control our own narrative because that’s a human fucking right. Sexuality isn’t everything, but to me, it is a representation of freedom because that was the first real restriction I faced in my life, and I think many others faced it too. I think women especially have to deal with the double standard of not being able to deal with the freedom of being a sexual being. In my work, I can own my sexuality. I can be who I want to be in my work.

Billy De Luca: So it’s more than just you?

Kate Ahn: In a way, it is more than me. I think my work can become confusing as I am trying to fight the patriarchy, but at the same time, I am also trying to heal from my own self-esteem issues that may very well come from the male gaze. Critics could say I am just perpetuating the patriarch all over again, and I hate to say it, but maybe they would be somewhat true. But I can’t help the fact that being able to fantasise about myself in these various bodies and shapes helps me appreciate my actual body. It’s similar to how I play with clothing, I put it on like a mask and play this character enough to learn that my real self is actually not far away from my ideal self…it was just my anxiety and self-doubt clouding my brain. Maybe that’s unhealthy in some way, but I think a lot of people can relate to the journey of finding true love for yourself and that sometimes it takes unconventional ways to get there. And at the end of the day, I believe that by taking control of my own body and my own self-esteem issues, I still, in many ways, fight the patriarchy.

Billy De Luca: Does the commentary influence you as much as it pushes you forward?

Kate Ahn: With or without the commentary, the paintings would still be like this. But it does help my narrative. The more hate I get, the more my paintings will develop meaning. It just proves to me what I need to express in my work and why it’s important. Some people think I just paint porn…but for me, I feel like I sometimes do paint porn, and there shouldn’t be anything wrong with that.

Billy De Luca: Is it hard to balance professional composure while being a human behind the work?

Kate Ahn: Yah, it is difficult– at least for me, it is. I mean, being an artist to me means that you are choosing to be vulnerable. I know many artists that can keep the vulnerability strictly within their work but for me, I am, unfortunately, a person who tends to word-vomit everything I am going through within my work and outside of it too. I know it’s not the best habit. I know most people respect those who have that perfect ‘professional composure’ — characterised by a confident fearlessness, keeping their cool, even when shit is going sideways in their personal life. This might be completely delusional, but I’d still prefer to find a way to continue to be this open book and also be respected for it just because I feel like it’s so much a part of my character.

Billy De Luca: However, having strong work which is the best thing that you put out at that time. That is what is going to be a huge driving factor. You might not sell. You might go from being very financially comfortable to financially uncomfortable. But through that ringer, one thing is still chugging along, still developing. And that’s your painting.

Kate Ahn: That’s right. And that’s why I’ll never stop either. The paintings are me. There’s no costume or façade or anything. It’s my soul. If I think back to where I was two years ago with my painting, it’s like…incomparable to my skill now. So yeah, that helps me feel better. These feelings of insecurity have inspired me so far, and although I’m working on that, it does still help me produce. The emotions come out, and it makes the art worthwhile. You don’t have to be ‘healed’ to make people feel something — I think I’m just too hard on myself since the years are never easy, and there are so many constant changes. Even if it’s bad feelings, it’s feeling. If you’re feeling something, it’s art.

Billy De Luca: And what else do you see is changing?

Kate Ahn: For my new collection, I want to do more facial expressions similar to the whole 1970s erotica time period, where everyone looked so happy, vibrant, and alive. I feel like that is true for me since I’m a very smiley and happy person. I also want to continue to include more pieces of clothing and lots more socks, as that still is so much a part of me. I did do that a lot this year as I did, like… a lot of stocks.

Billy De Luca: I was going to ask about those…It reminds me of how men in the business sector ‘jazz up’ a suit with a sock. You end up being naked, showing the socks you wear, and they can be colourful and different, but they balance out the grey world of suits. It’s a stabiliser.

Kate Ahn: It’s an homage to my love of clothing…In a way that still allows me to be nude. Certain things go on when you conform to such a society. It’s so difficult to show your identity and be unique and yourself. So yeah, socks are awesome, and you can have so many cool socks.

I’m obsessed with socks.

Billy De Luca: Besides the clothing, where do the colourful backgrounds come into it? Do the star-shaped pastels of pink and green come as afterthoughts?

Kate Ahn: The background comes later. I usually don’t know what to do for the background. That being said, I feel like it has to do with my inspiration from Japan, especially from love hotels. Japan is just…different. I want the paintings to feel happy and alive. I learned a lot about love hotels recently. Back in the 70s, during the women’s liberation movement and just after they legalised abortion, all these love hotels popped up, and they embraced and nurtured the idea of sex and love. You can see it in the way they built these themed rooms and structures. It’s a fantasy that invites more fantasy. The beds are spinning, there’s colour everywhere, and the adult fantasy becomes a reality. And I love it. I love how it is accepting of the fact that humans are sexual beings. It’s happy and human.

Billy De Luca: And does your subject matter and work rely on where you are geographically?

Kate Ahn: Yah, I definitely think so. When I grew up in the suburbs, the constraints and staleness of the city definitely played a part in my work and also the person I became. That’s where you can see the rebellious nature of my work. And being that I was only an hour away from LA, it became a dream of mine from an early age to move here — which I finally did at 18. I think the environment here in LA is so nurturing to being different. It helped me gain confidence in my work. And the actual physical beauty of the city — the madness, the graffiti, I would say some of the strip clubs down here, too, have definitely inspired some of my works.

Billy De Luca: Being in LA is historically seen as…intense. ‘Jasper Johns once said that Hollywood is forever young, forever sexy, and forever swollen with abundance.’ How do you feel about LA?

Kate Ahn: I think Jasper Johns is right. LA is forever young, sexy, and so swollen with abundance that I think it’s only natural to have this love-hate relationship with the city. You can’t be young forever. BUT maybe you can be sexy forever — depending on who’s looking — but living life in abundance will always catch up to you. That’s the thing with LA as much as it is a beautiful city, it’s also really superficial, but hey, I think you can find that just about anywhere in the world. I hate it here, but I also love it, and it will always be my home.

Billy De Luca: Last question… Does that solitude drive you to keep going?

Kate Ahn: I don’t know if it really drives me. I think I am just so used to being alone. Being an only child basically prepared me to be an artist, you know? I think what drives me is that from a very young age, I had a dream of who I was going to be when I became a grown-up, and even though I still have ways to go, I am essentially living it. Even with all the people trying to bring me down and bet on my downfall, I will never let go of my dream. That’s what will always drive me to keep going.