In The Middle of It All

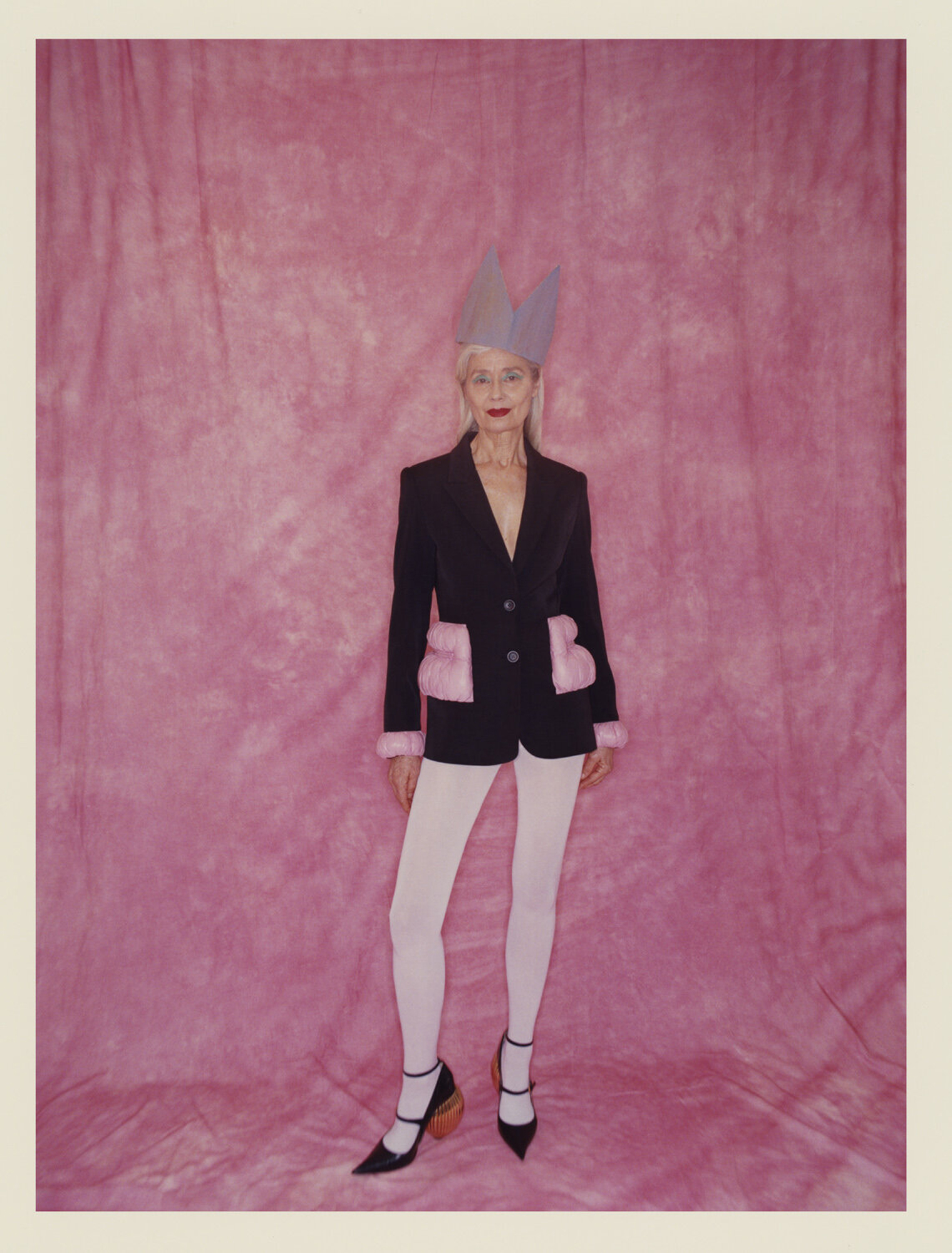

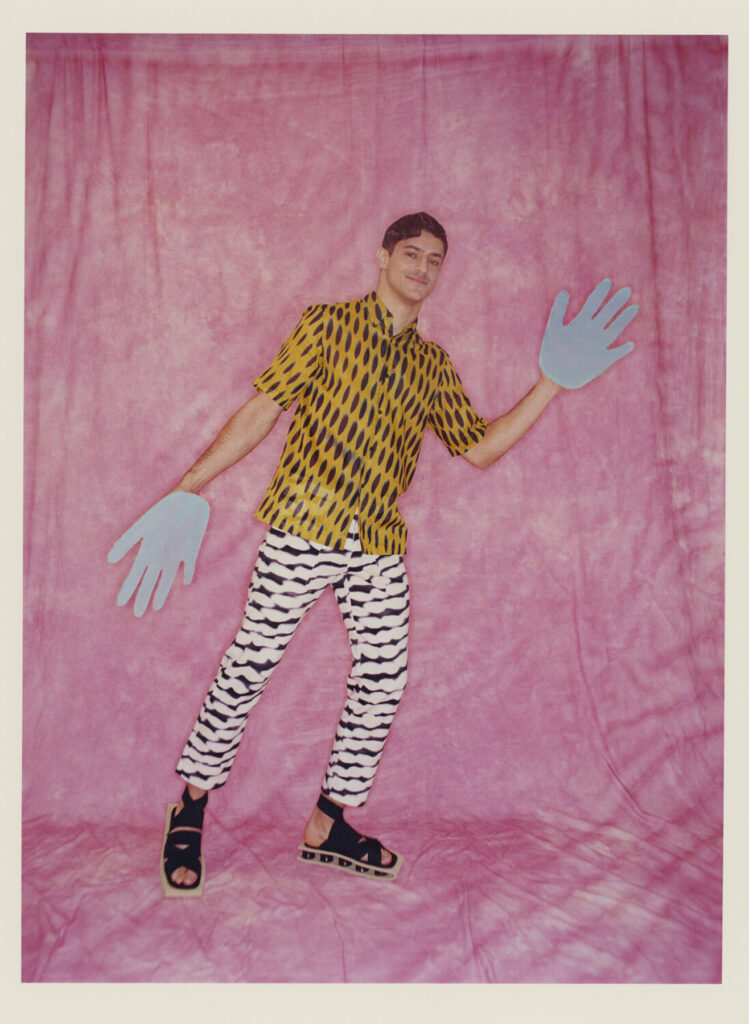

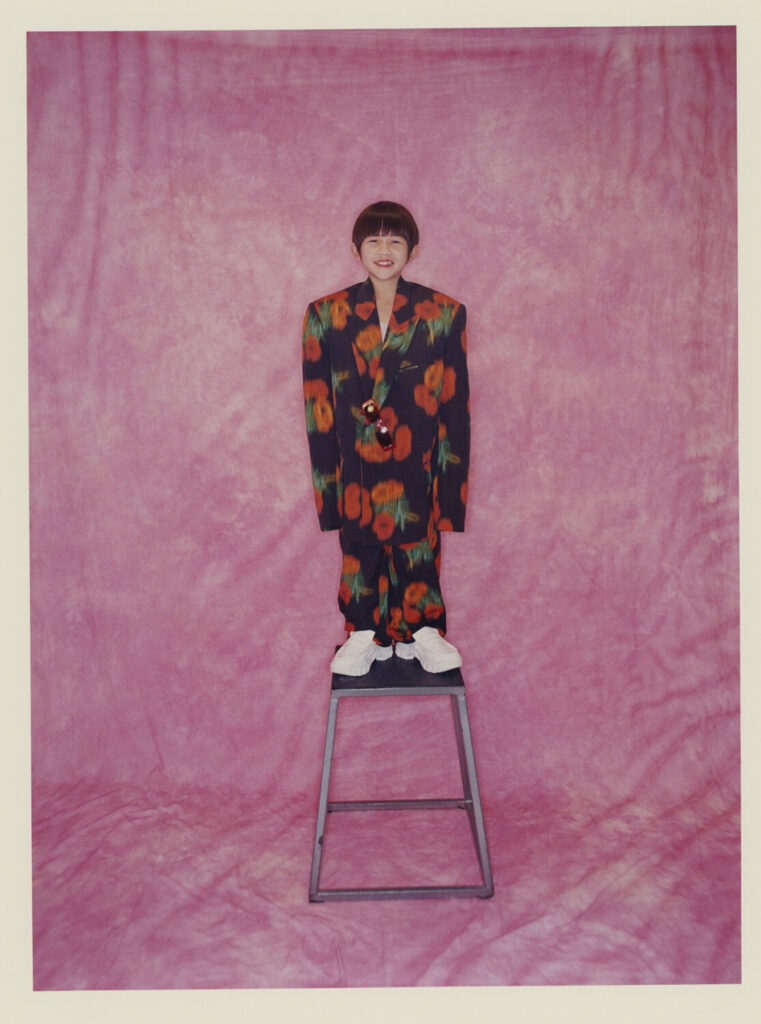

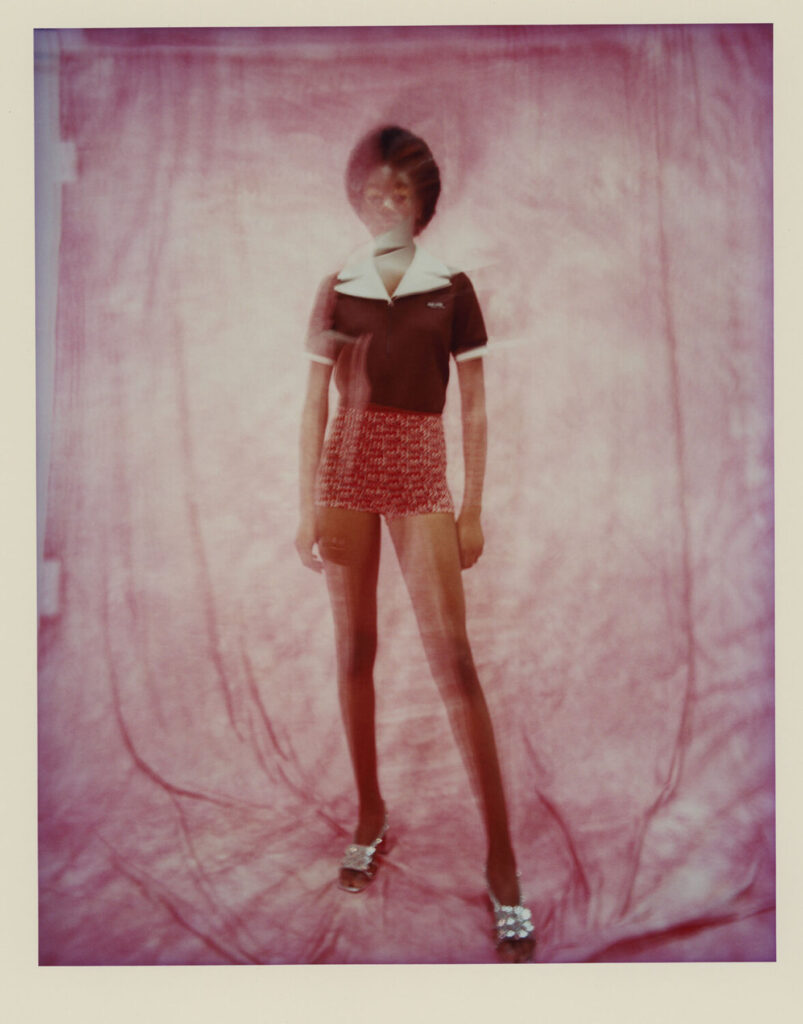

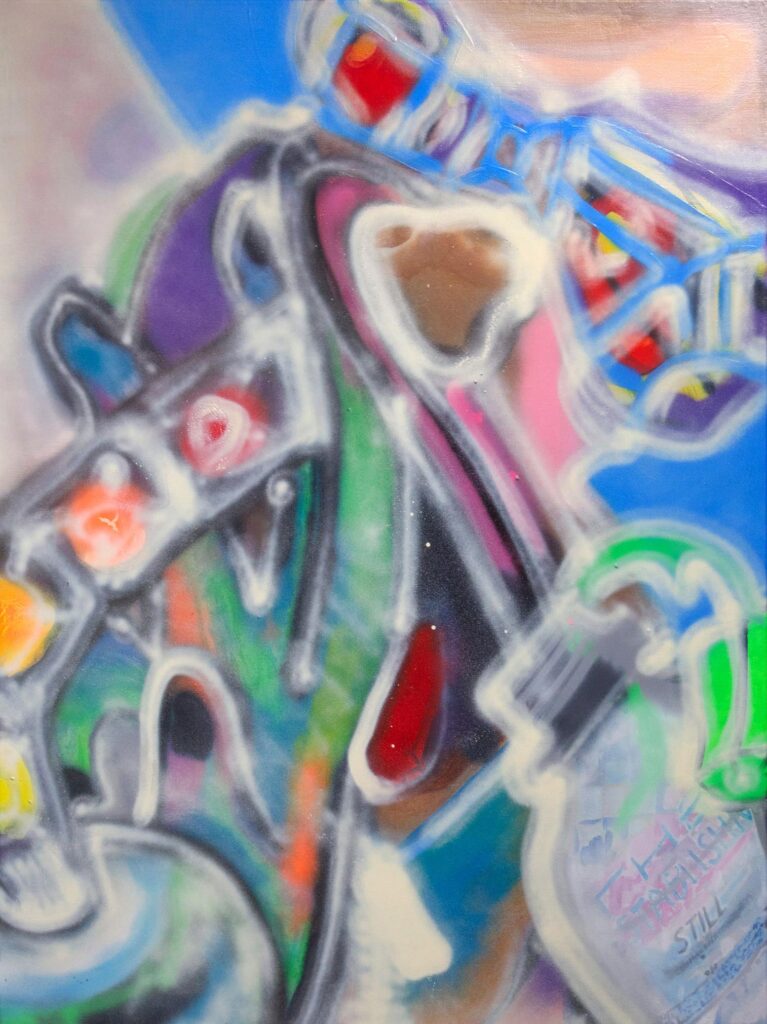

Claire Barrow’s work balances in between worlds of pop culture, politics and ethereal creatures. With a combination of the media she consumes and the topics she’s passionate about, the result is an unexpected display of these themes colliding into different disciplines. Whether it’s paintings, sculptures or illustrations she has dreamed up and then translated onto clothing, her art is boundless and unpredictable.

Born in Yarm, a town in Northern England, Barrow grew up watching Disney films on repeat and listening to bands like Slayer and Sonic Youth. Daydreams of moving out of her small town and a career in fashion didn’t seem so far-fetched when she moved to London in 2008. She studied fashion design and it was not long after, her career in fashion started to bloom. Catching the eyes of industry leaders Barrow describes her move out of the traditional fashion calendar to be more freeing and expressive.

“I’m grateful to come from a fashion background, there’s been so many benefits and collaborations that have evolved from my history within that but I’m also grateful I can pick and choose when to enter back into that world, it’s not about money for me,”

Barrow tells me over Zoom, behind her lies a stack of boxes and canvases ready to be moved after almost 10 years of living in the same house and studio space.

There are many passions and interests Barrow weaves into her work– her theater upbringing, fashion and makeup seamlessly appear through her work. Her most recent show, Victim of Cosmetics, presented in an office space was inspired by the wasteful nature of the beauty industry. Currently, Barrow is in the midst of expanding her studio space, where she’s excited to create more sculpture work.

In this very exclusive interview we catch up about inspiration, creating in a climate crisis and pop culture.

Jessica Canje: The venues you pick to showcase these shows are often unique like the Piccadilly Tube station or a reformed office space, how do the venues you pick intersect with that specific show?

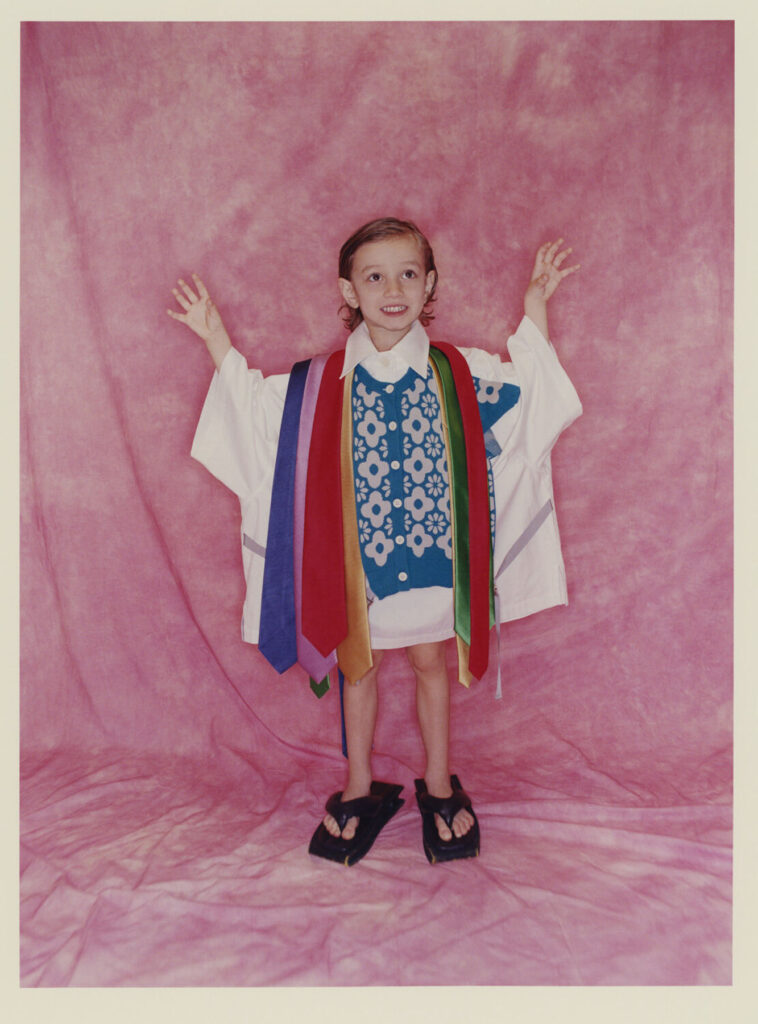

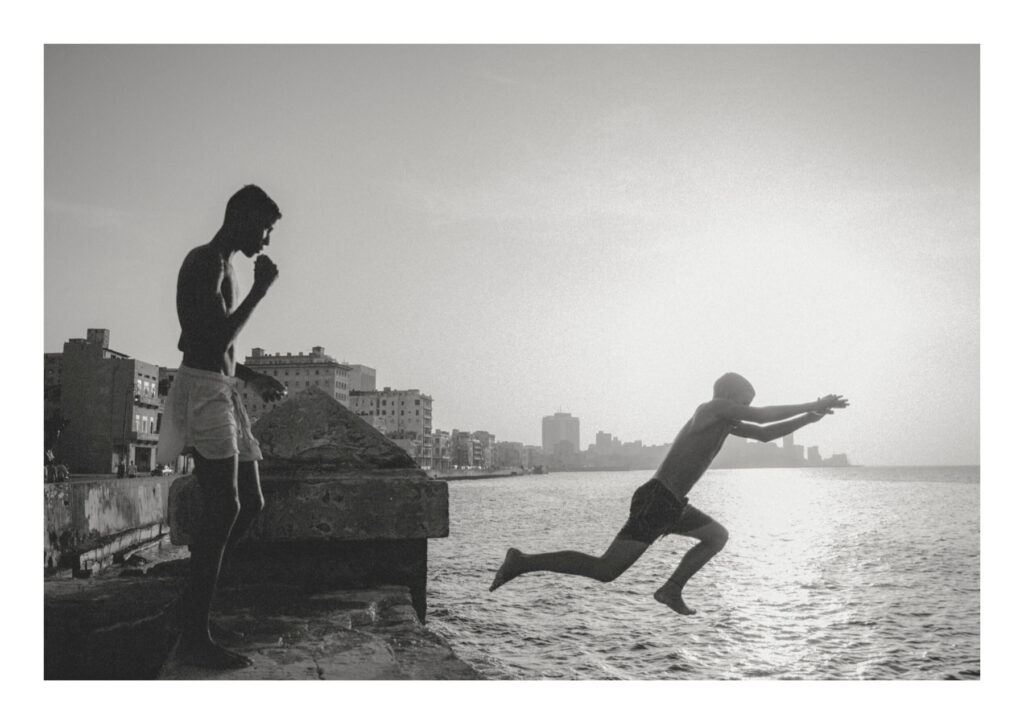

Claire Barrow: I love to build worlds that resemble the spaces you visit in dreams, trapped places, and half-remembered theme parks from childhood, the big supermarket where your mom dragged you around that felt like an eternity. Recurring places and scenarios stick with you and get filed in your brain’s office cabinet. The feng shui is off.

The tube station (Piccadilly Circus) was thanks to Soft Opening for inviting me (thanks 👍), but otherwise, the office, the field in Hackney where I did a show, and my website reflect this kind of experience. Being big into games and theme parks as a kid, and then in my teens and 20s, creating fashion presentations and experimenting with the use of space to showcase my collections. It’s something that has stuck with me as I’ve transitioned into making art my primary practice, and I would love to explore it further going forward.

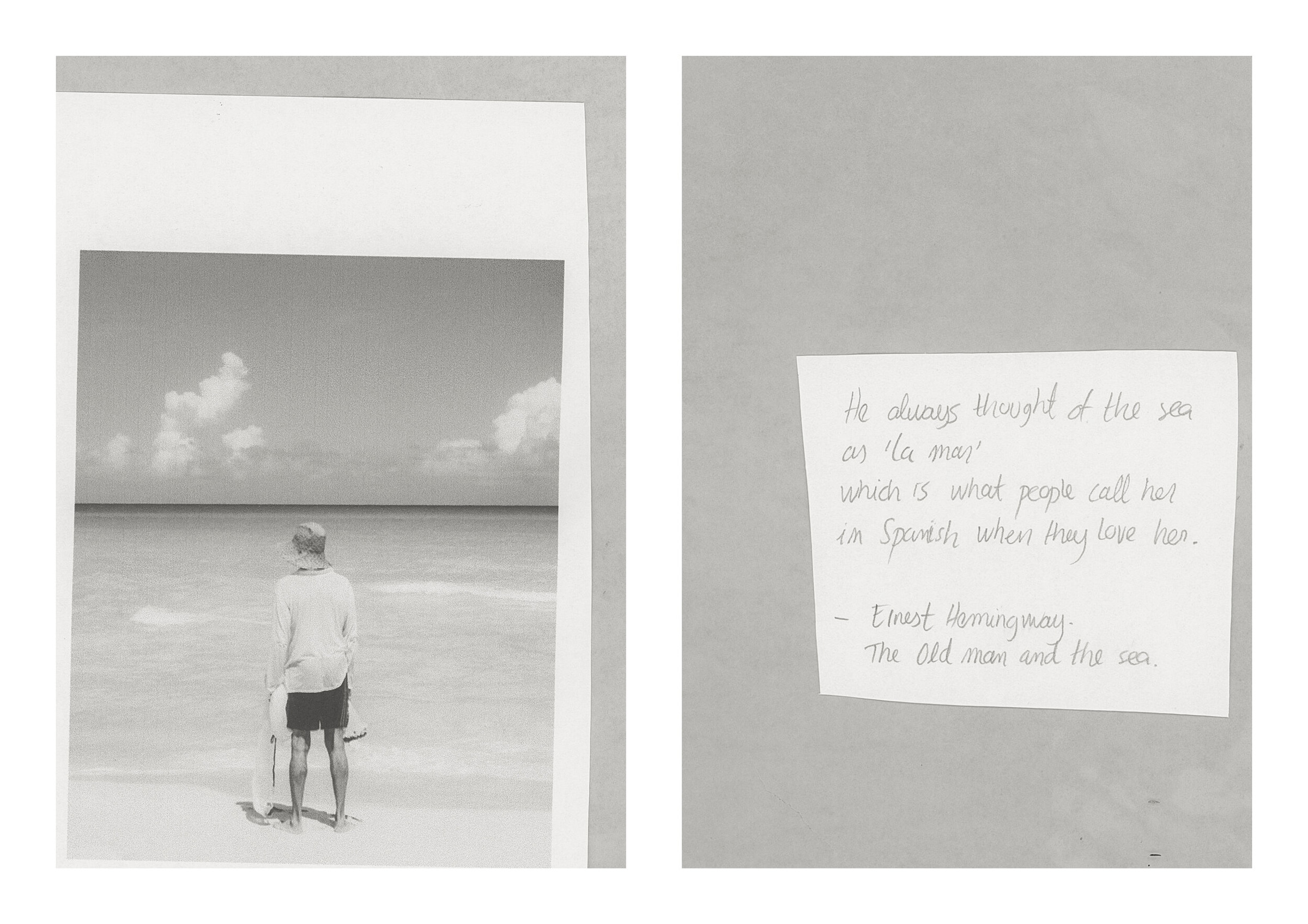

Jessica Canje: I love your current website, do you often think about how people will interact with your work virtually if they don’t get to experience it physically? What was the thought going into making your website the way it is? Can you describe it for those that may not have seen it or may never get to?

Claire Barrow: Glad you like ! So, it was created in collaboration with Rifke Sandler of DXR Zone, who formatted and coded it. The site is heavily inspired by early, now-defunct net platforms such as Active Worlds and Geocities and it functions as a hybrid of an 3D online museum, an underground bunker, and a frozen metaverse of my current art and archive, complete with a gift shop! It is designed so that you can navigate it with clicks, clicking on different areas to move around the site. When you first enter, you find yourself in a field with earth in the sky above you. Going into the pink Wendy house with the blue roof in the garden leads you underground into the foyer, where you can choose a door and explore different galleries. The galleries feature 3D renders of my art, sometimes flat to the wall, and sometimes arranged in themed rooms, secret passageways, with soundtracks and GIFs. There is the option to view it all in 2D instead, if you’re that way inclined, or too confused.

Essentially, this platform serves as a way of inviting people to view a gallery showing of my work, outside of the traditional gallery system or Instagram, irrespective of their location. So, when I’m exhibiting work physically in a specific location, I think it’s nice for people who can’t attend in person still have a way to engage with it through this platform. I understand 3D viewing rooms at Art Fairs are becoming super popular, so I’m leaning into the trend in my own way.

Jessica Canje: Your last show was partly inspired by the wasteful nature of the cosmetic industry–how do you feel about the impending doom of climate change and waste? How does it translate into your work? /

A name from your recent show Victim of Cosmetics came from a quote by Khloe Kardashian, Bury Me In Lip Kits and Eyeshadows, 2023 –

Is your work intuition led or is it through thought and research and much deliberation?

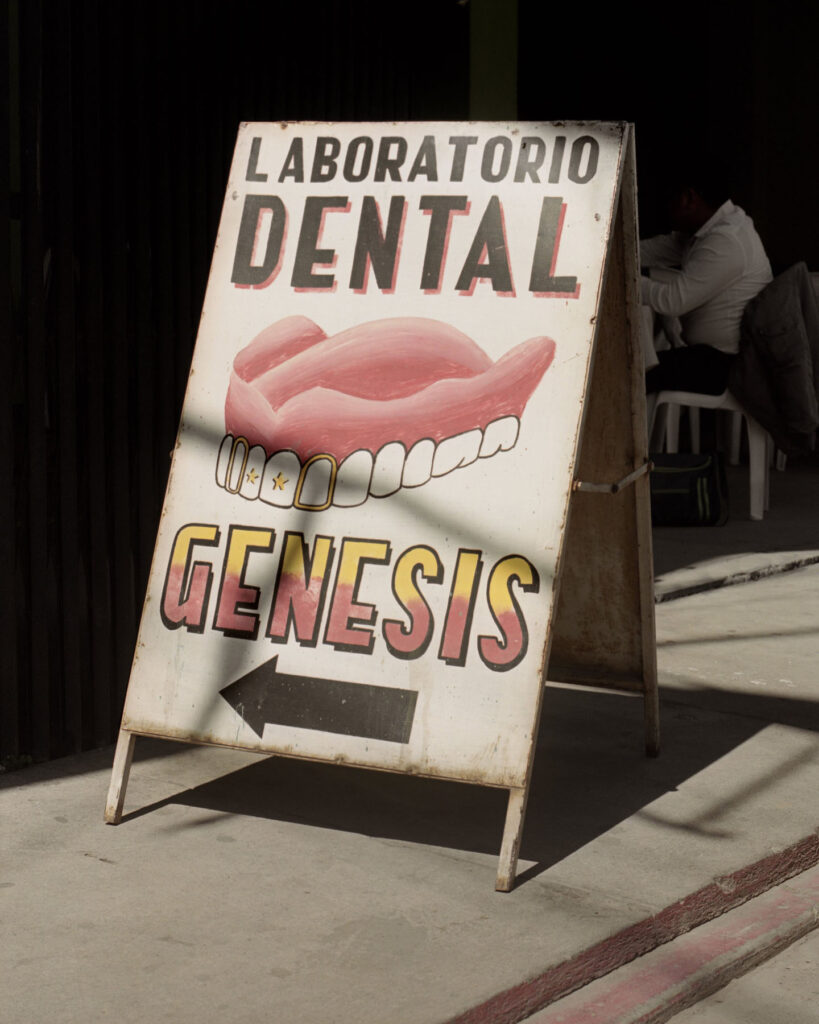

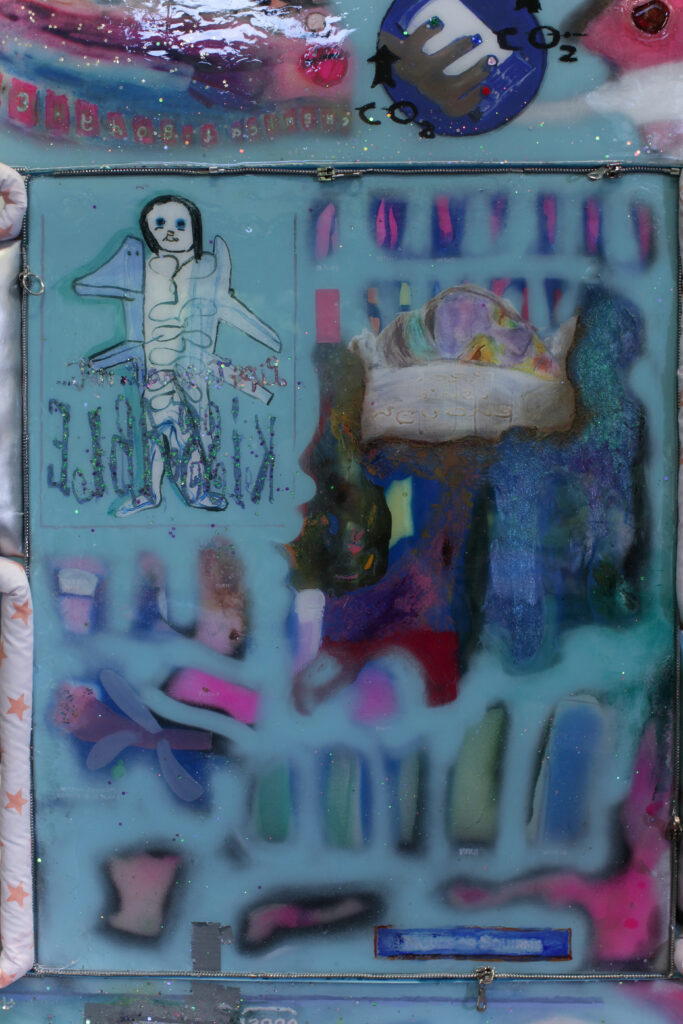

Claire Barrow: I got the title from this lady, Maria Gunning, Countess of Coventry, who died 1760 from the lead poisoning caused by her makeup. She was a superstar beauty icon, like the Angelina of her day, and named the “Victim of Cosmetics” in the papers.

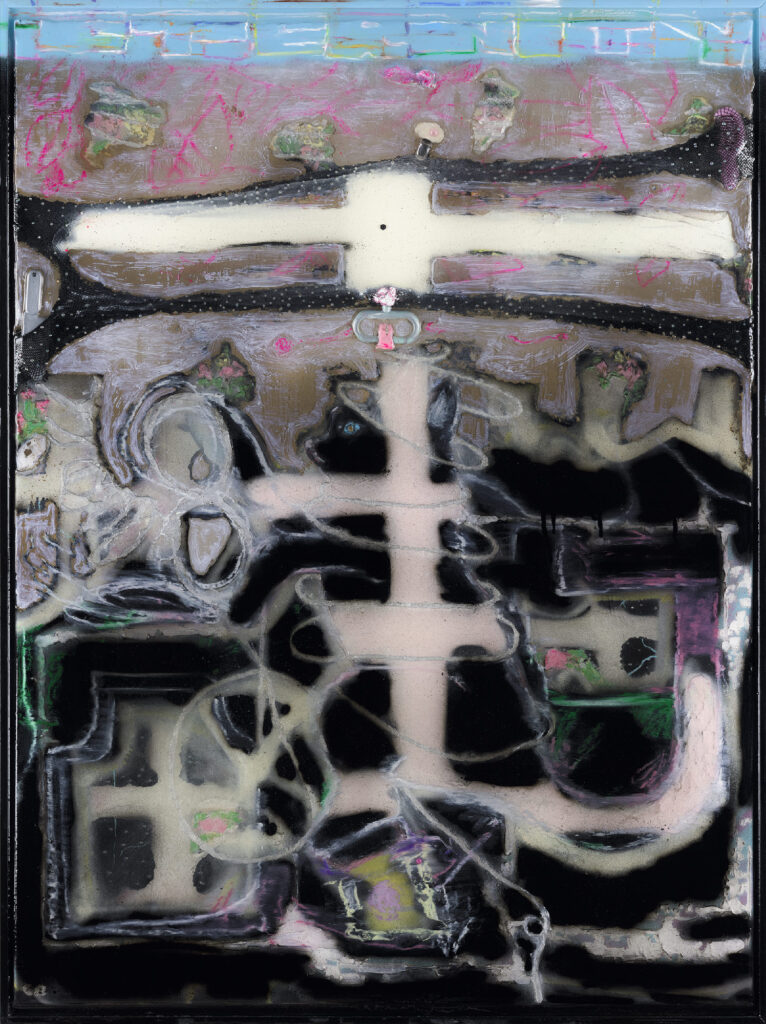

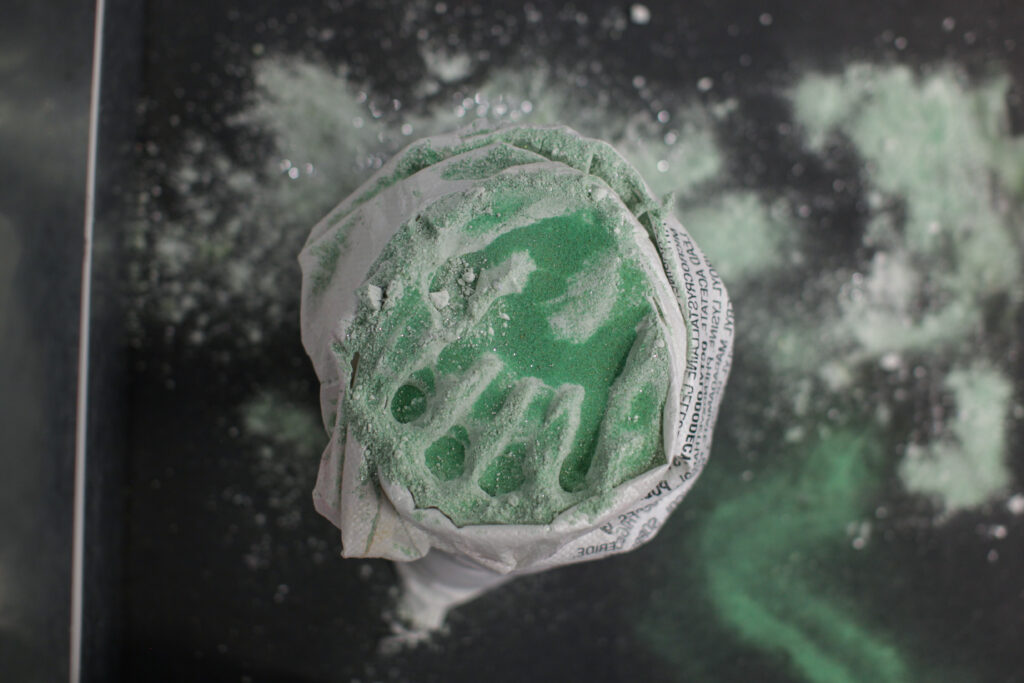

This body of work was heavily research-based, more than most of my others, which have been led by absorbing my reference points into something initiative. But still I used intuitive techniques; like, I was often creating wet canvas then applying paint, allowing it to dry then informing the structure of the painting. Before the invention of the world in the 1640s cosmetics were referred to in general terms as ‘paint’, so I used paint, and dyed concrete powder.

My algorithm selected this project for me, it’s just something I felt I had to make due to the images and research I was receiving. Then it further developed into a response to beauty capitalism and pressure to work hard in the beauty and cosmetic production industry. The sculptures resemble inside-out makeup bags, keeping things hidden inside them, but flipped out.

I re-watched the Kardashians, from top, everyday while making the show. Which was such a slog and depressing, honestly.

But I was to try and pinpoint a time when the world changed and yassified itself, like they did, valuing beauty and perfection above all else. It was around season 12, a few years after Kylie’s Lipkit success.

Jessica Canje: You’ve been based in London for quite some time now, how is the creative atmosphere in the city at the moment?

Claire Barrow: A claustrophobic feeling of coexisting but it’s exciting and scary and fun, and being a bit shit, but that’s ok.

Jessica Canje: It’s always exciting seeing you release new work as you’re often reinventing your output, what can we expect to see more of in the future?

Claire Barrow: I’ve just just moved my studio to Camden, the punk graveyard, I think it will have an impact shortly. I hope to give back more, to be strange and brave… and make up some dances.

Jessica Canje: Have you seen Barbie?

Claire Barrow: Yeah I liked it. It didn’t talk about anything to do with plastic, I thought it was quite interesting, you know? In the midst of a climate crisis. It’s a crazy waste of plastic, all these toys with non recycled plastic.

Jessica Canje: Do you like sci fi?

Claire Barrow: I love Sci Fi and horror and tacky action films I’ve been really into. I love John Wu films.

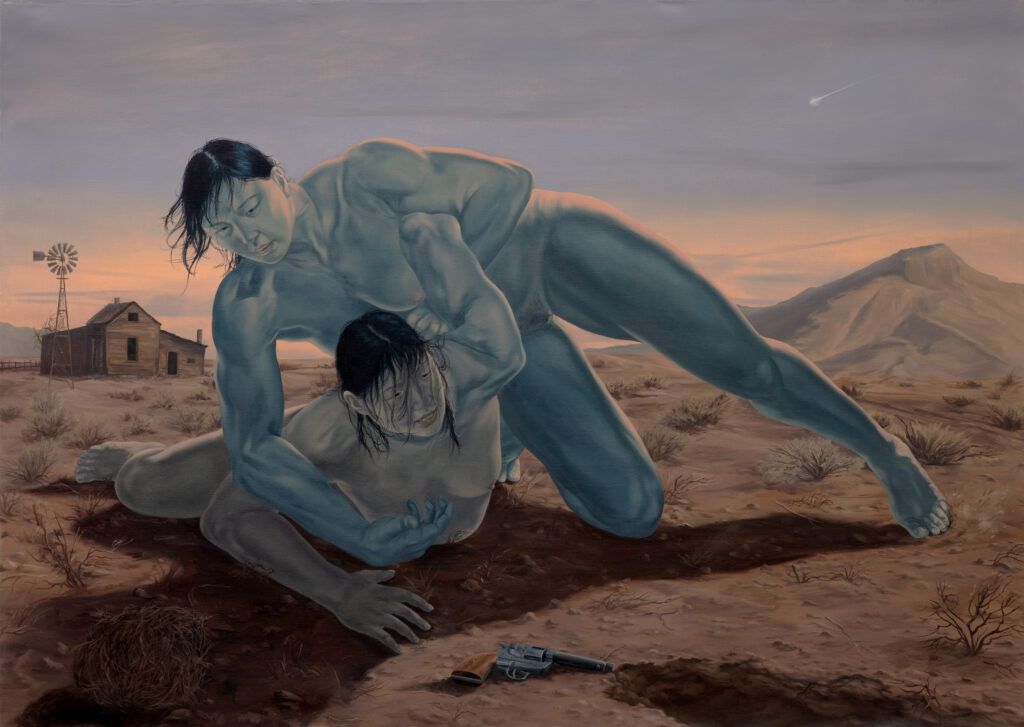

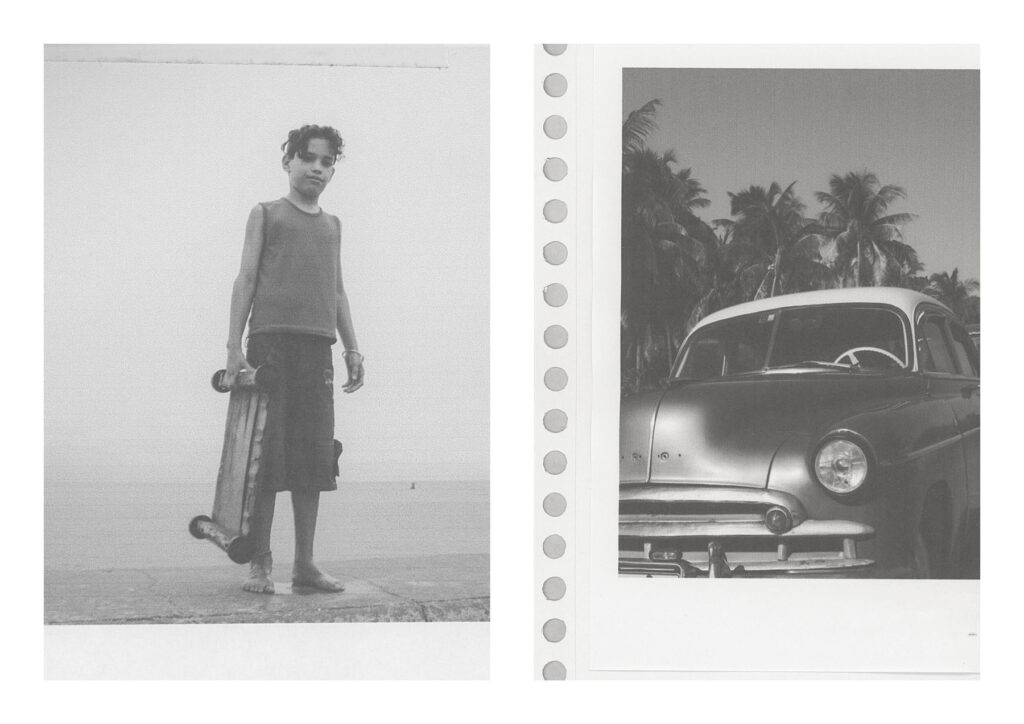

Artworks

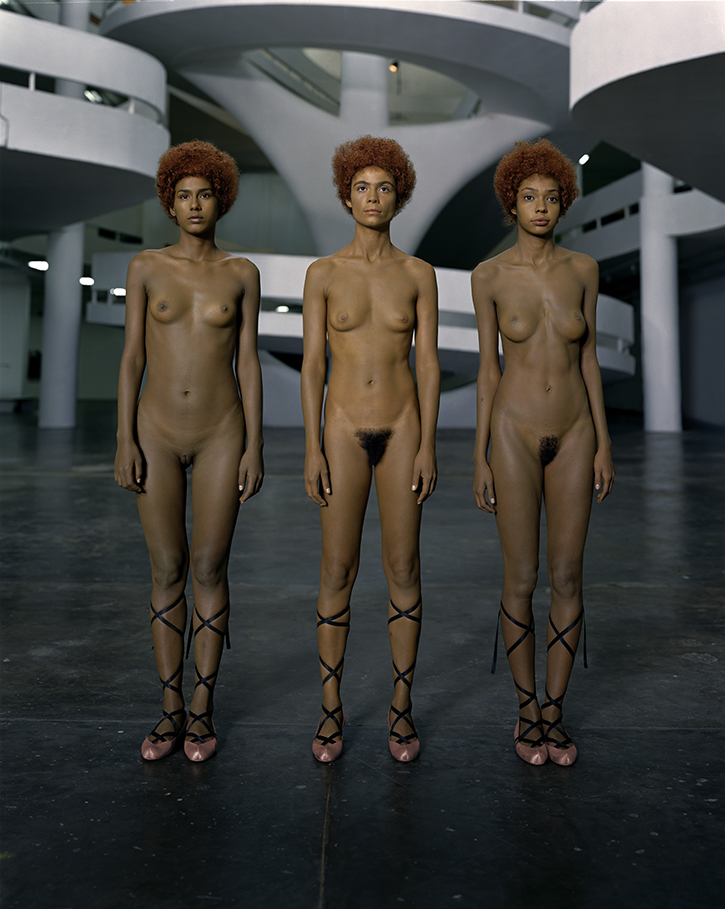

- THE BOTTOM, 2022

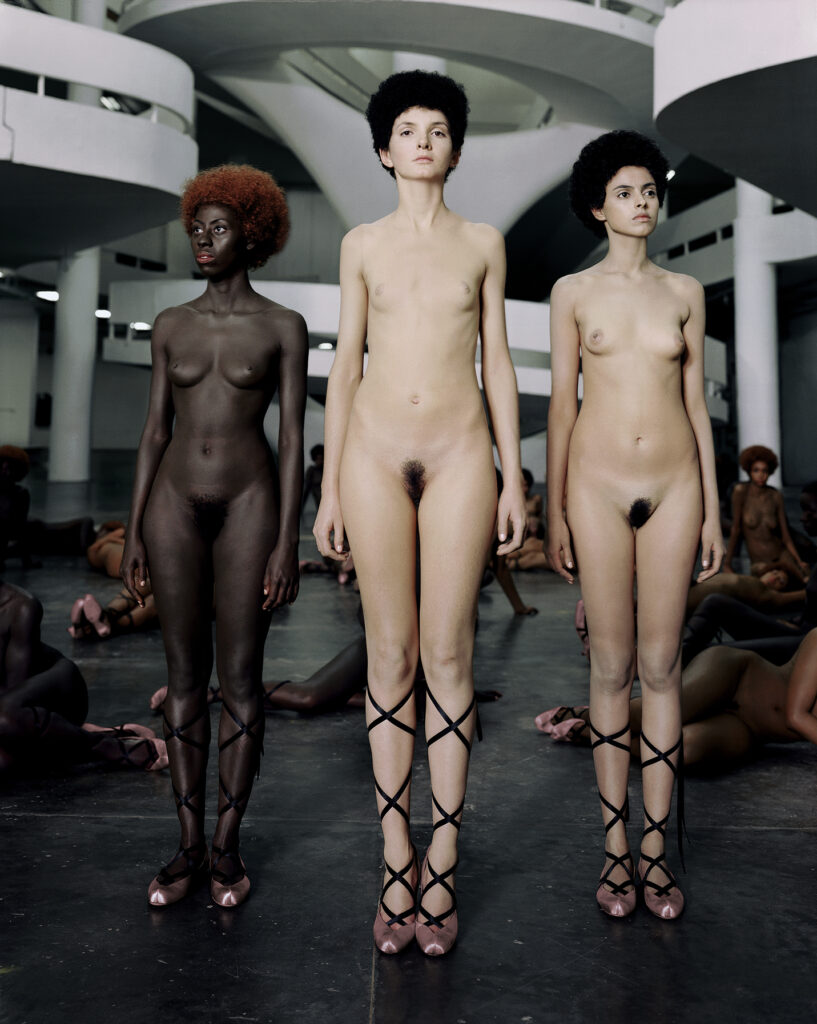

- ETERNITY BITCH, 2023. Installation View

- PIPE, Dinner Party Gallery, 2021

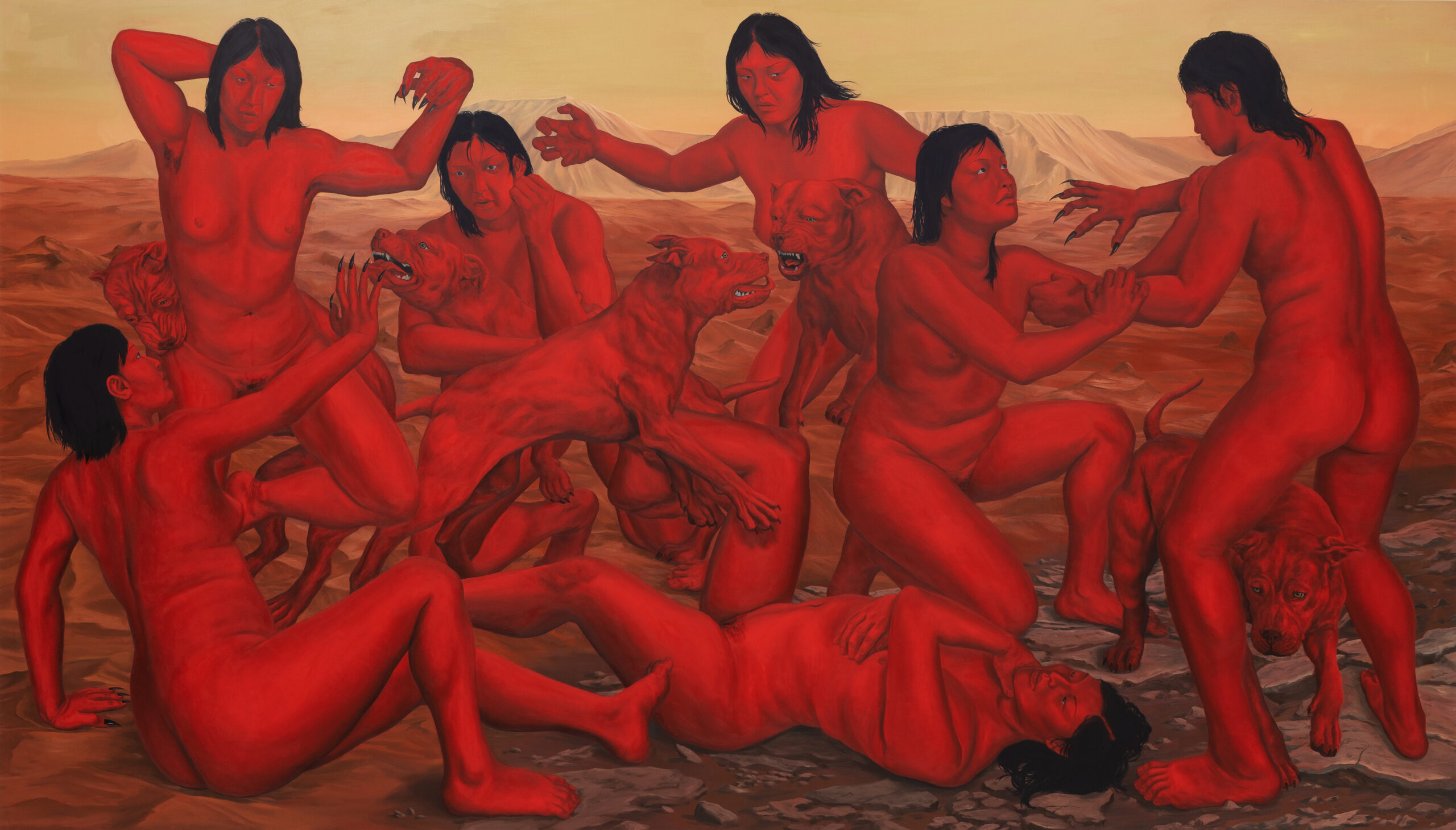

- THE ESTABLISHMENT

- VICTIM OF COSMETICS, 2023. Installation View. Fieldworks, 2023

All artworks courtesy of the artist