Film director and photographer Neels Castillon on cinematic visuals

For Neels Castillon, authenticity is integral to his role as a film director and photographer, especially, as he explains on the phone from Paris, in an age of fake news. The dissemination of falsified and fabricated news reportage may not have a direct connection to Castillon, whose clients include Lacoste, Hermès and the French singer, Angèle, but his contention lies with the prevalence of artifice. He sees his role as navigating a balance between capturing the feeling that cinematic visuals can provoke, whilst simultaneously resisting the artificiality those same visuals can carry. There is perhaps no better example of how Castillon meets this feat than in his production company, Motion Palace’s, advertising campaign for kitchen manufacturer, Schmidt. The premise of the advertisement was to have one of Schmidt’s kitchens appearing on a cliff face, demonstrating the brand’s functionality and adaptability. On seeing that the brief was to shoot in a studio with a green screen, Castillon responded that it should be shot for real in the Alps. The ensuing advertisement, and supplementary documentary about the process, are jaw-dropping to watch, as mountaineer Kenton Cool makes himself breakfast in a fully-working kitchen, 6500ft above ground. Castillon refers to the experience as a ‘cool adventure’; the team involved stayed in tents for fifteen days, hiking their way up to the cliffside, and creating an entirely new structure to support the camera from above.

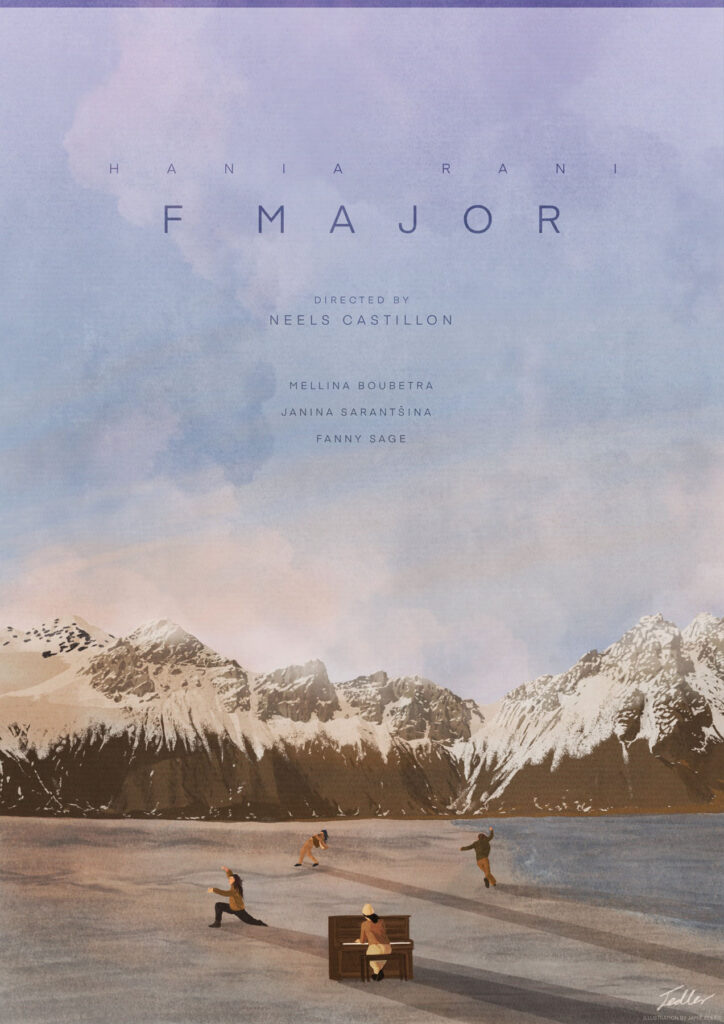

It is through commercial work, like the advertisement for Schmidt, that Motion Palace is able to pursue its more artistic endeavours; ‘It’s in the DNA of my company to produce art stuff with the money we make,’ Castillon explains. As a result, Castillon was able to realise the F Major music video for the neo-classical pianist, Hania Rani, in Iceland earlier this year.

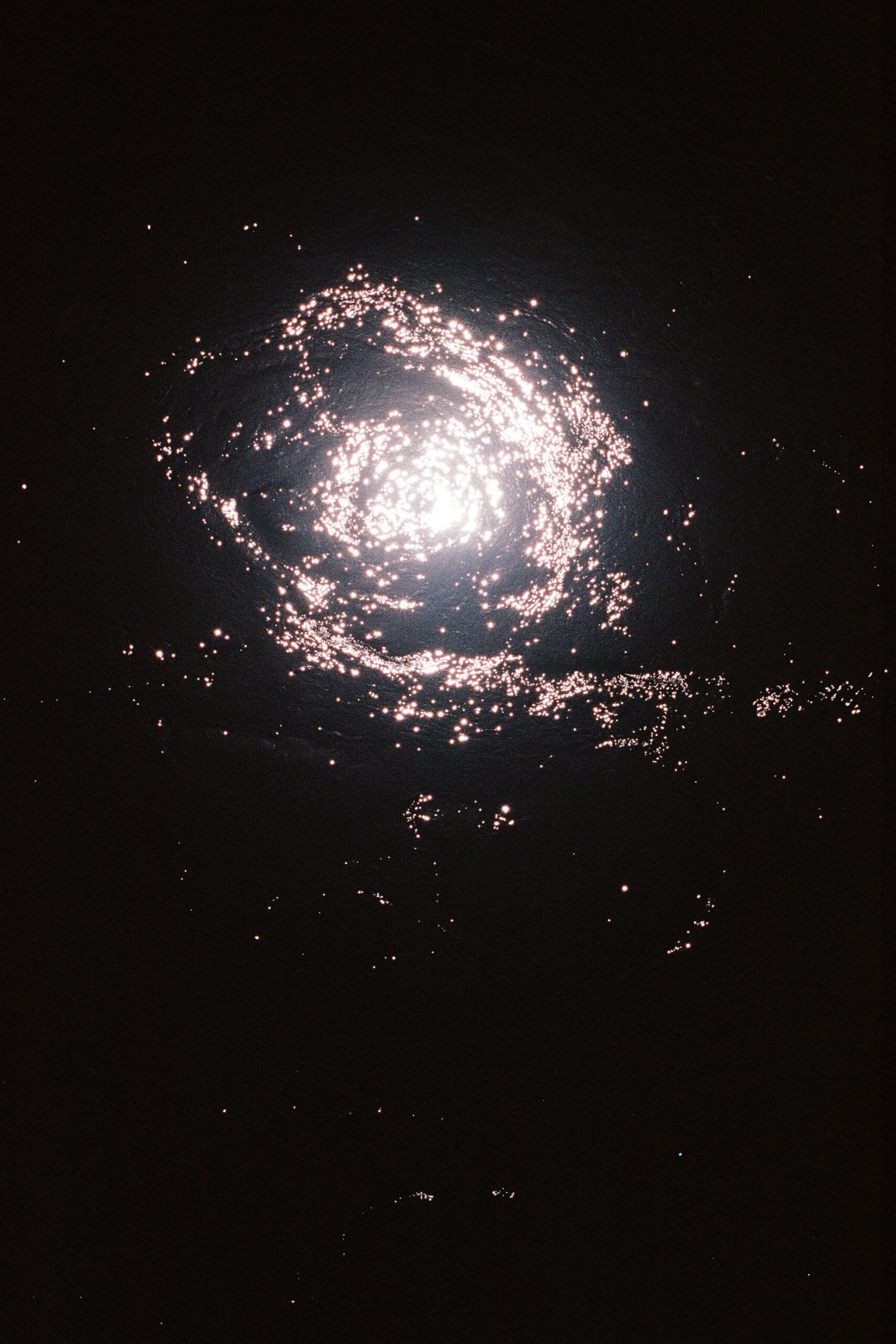

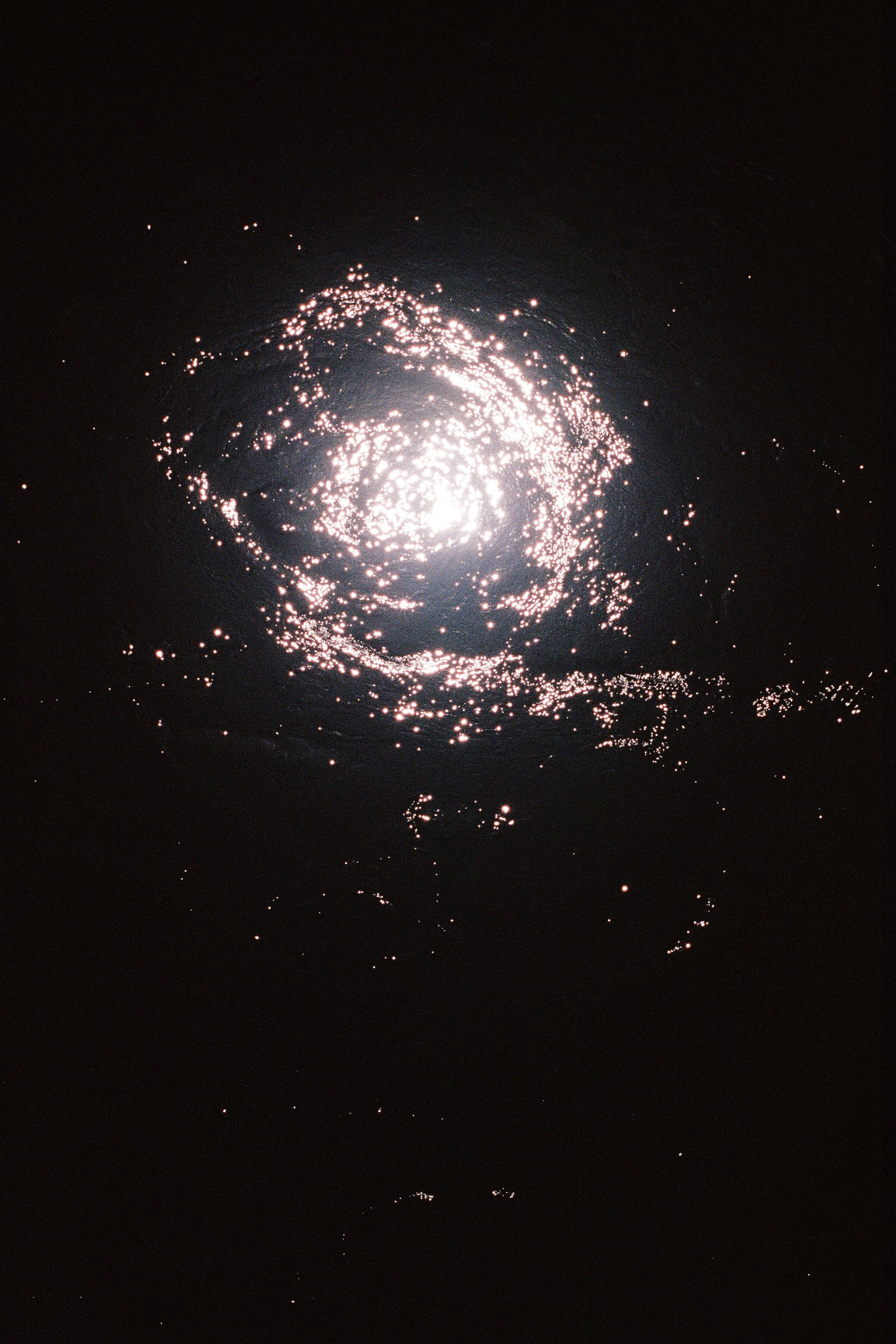

Filmed in a remote location, Hania is seen playing an open-front upright piano – an approach which visually encapsulates the artist’s fascination with the mechanical, organic possibilities that the instrument affords. For the video, Castillon worked with the choreographer, Fanny Sage, and the dancers Mellina Boubetra and Janina Sarantšina, whose interpretations of Hania’s ethereal performance is captured in a single sequence shot. The camera work signals Castillon’s commitment to striving for authenticity; ‘The concept was, how can we translate music that never stops, and keep up this pace?’ So, the camera doesn’t stop either. It was important, too, to translate the sensation of freedom that comes both with Hania’s music and the dancers’ movements – something that the film’s location allowed for. ‘I want to celebrate nature,’ Castillon explains, adding that he strives to capture how a landscape can be inspirational, whilst resisting the urge to just create picture postcards of the scenery. The backdrop of mountains and black sand in F Major have the potential to be just that; awe-inspiring and spectacular in itself. But, as the chilling wind that entraps Hania and the dancers in the video confirms, the logistics of F Major were anything but straightforward. ‘As you can see, there was an ice storm,’ Castillon points out; ‘It was very cold, like minus seven degrees. We rehearsed a lot before but, on set on the beach we only had three takes because of the light and the weather.’ Not only was the filming testament to Castillon’s approach to taking on a challenge, but also his dedication to fully realising the potential of the performers he works with.

Castillon discovered Hania Rani through her record label, Gondwana Records: ‘I like pretty much all the artists they have in their roster, so when I listened to her first album (2019’s Esja) I was totally in love.’ At the time Castillon reached out to Hania, she was writing her second album, Home, but she had seen Castillon’s 2017 film, Isola with the dancer Léo Walk, and wanted to work together. Their collaboration was postponed to allow time for Castillon to raise money and for Hania to complete the album. This time also gave Castillon the chance to work out the concept for their work; ‘I listened to [F Major] maybe 200 times before coming up with the idea.’ He was also keen to ensure he attended every rehearsal and discuss the concept with the dancers; the process is ‘almost a co-creation,’ Castillon explains, like ‘ping-pong.’ It’s a constructive and collaborative process of back-and-forths to find a way that Castillon can capture the performance in the best possible way. His work with Hania may have been a while in the making, but that seems to be the case with a lot of Castillon’s collaborations.

Stills from Hania Rani’s F Major music video

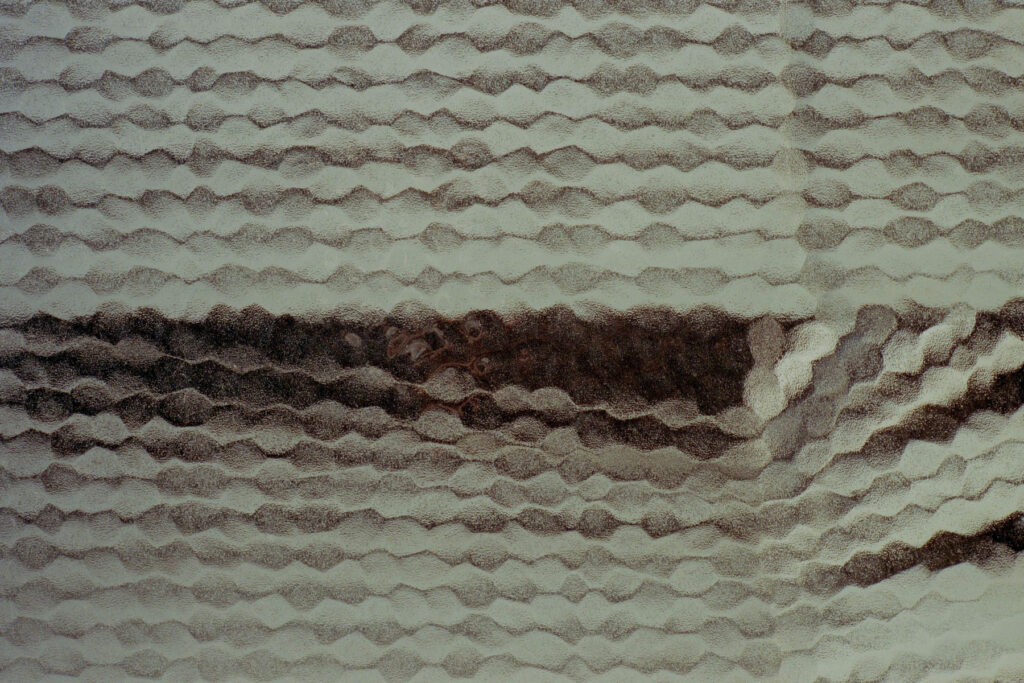

There is a sense, talking to Castillon, that he uses his films to capture the creative endeavours of those he knows and admires – and in turn, to introduce them to one another in the name of collaboration. That was the case for last year’s short film, Parce Que, featuring the painter, Inès Longevial, and Léo Walk. Inès, like Hania after her, had seen Isola and was keen to work with Léo who, similarly, loved the painter’s work. Castillon had known Inès for a number of years previously and was waiting for the perfect opportunity to work together, which Parce Que would be – but it took ‘almost a year to find a time when [Léo and Inès] were both available.’ The idea was to combine painting and dance together, but Castillon was wary of avoiding the pitfalls of an ‘arty cliché’. With Serge Gainsbourg’s song Parce Que as the film’s soundtrack, the dangers of doing something cliché could be high, but Castillon managed to pull it off. That success is demonstrative of the director’s integrity when it comes to understanding the performers he works with. It was important that the location choice for Parce Que would be able to accommodate Léo’s dancing, which, as he explains in reference to Isola, requires a smooth enough surface to allow for some of the breakdancing moves. As the film, which tells the story of love and, eventually heartbreak, progresses, Léo dances on a six by four metre painting that Inès is depicted as working on; Castillon’s way of combining the creative skill of both collaborators, and avoiding the cliché of something ‘that has already been seen before’.

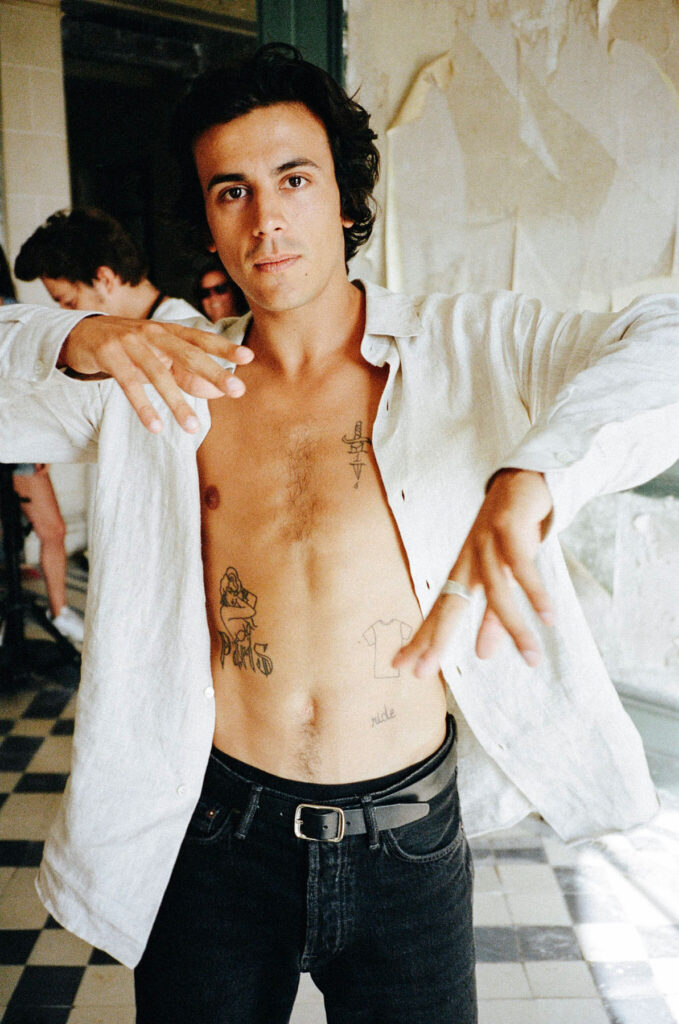

Léo Walk on the set of Parce Que

Inès Longevial on the set of Parce Que

As with the Schimdt advertisement and the F Major video, Parce Que shows that Castillon is a master at pulling of impressive operations. ‘It’s what I love,’ he enthuses, ‘sometimes you have a crazy idea like, “What if Léo dances on a big painting?” And one year later, you are shooting it. Like, okay – it’s worth it.’ A special frame was made for Inès’s painting, which was kept in four parts in a friend’s shop in Paris because, as Castillon explains, ‘the apartments are very tiny’, before being transported to a secret location in the South of France for filming. A delipidated castle near Biarritz was chosen in part because the location reminded Inès of her childhood and also because Castillon liked its uniqueness. It had been designed by a woman at the turn of the twentieth century, who had taken inspiration from far and wide including, amongst other references, Versailles. Castillon is careful not to disclose the exact location of the castle because of the fragile state that the building is now in; the team spent two days clearing the site of detritus before filming and filmed quickly to cause as little damage as possible. There is, then, a sense of nostalgia that infuses Parce Que – a longing for lost love, a reminder of childhood and memory of times gone by.

Personal connections prove important to Castillon, perhaps another explanation for how he avoids clichés. During the location scouts for Isola, it occurred to Castillon that he knew exactly the place to film. Castillon grew up in Sardinia; he remembers a deserted building near a beach he used to frequent with his grandmother, which would become the ‘perfect place’ to film. He describes the place as surreal, the light there reminding him of an Edward Hopper painting. The experience of watching Isola feels similar to viewing a painting by Edward Hopper, too. To see Léo perform, at first refracting the haze of the summer sun and, later, his movements lit up by the warm glow of sundown, it is possible to feel connected to him in his solitude. Isola grants the opportunity to be close to Léo precisely because Castillon is conscientiously aware of the viewer. One of the director’s earlier videos, La République du Skateboard, came from the desire to capture a scene close to Castillon’s heart. As a skateboarder from the age of ten, Castillon started making skate videos using filming techniques common to the scene, ‘fisheyes, long lens – pretty dirty stuff.’ But, he decided to make a film that was more cinematic, taking influence from the classic movies that helped him learn the filming techniques he employs today. The film, about skateboarding and, skateboarding in Paris in particular, was envisioned as something that anyone could watch. The result is an ode to the scene and the city, beautifully shot, as would be expected from Castillon’s work, and accessible too. ‘I didn’t want to make something that only speaks to experts,’ the director explains. ‘I wanted to translate it in a way that is universal so that everyone can watch and understand why it’s beautiful.’ That same philosophy is applied to dance; ‘I’m not interested in making dance videos that only a few people can understand’, Castillon says of his approach. Rather, he wants to ‘find a perfect balance between the popular and the artistic.’

At its core, Castillon’s role as a director could be understood as transforming his fascination for performers into nuanced films that combine a highly cinematic approach with a deep respect for artistic craft. He says that he is fascinated by artists like Léo Walk and Fanny Sage, and this fascination inspires him to tell their stories. It’s somewhat telling that Castillon describes himself as someone who ‘cannot create a whole universe from nothing’. Rather, he thrives on the collaborative process that comes with the way he instinctively works. Just as he brings up fakes news as the anthesis of his search for authenticity, Castillon describes a ‘kind of boredom’ that comes with the saturation of content on platforms like Instagram and Netflix. He is resolutely not interested in making films that have been done before. That said, Castillon’s upcoming release sees the director return to Iceland with Fanny Sage for a second film; the music is by the French artist, Awir Leon, who, not surprisingly, Castillon claims to love. He describes the short film, called 間 (Ma), as ‘mind-blowing’ – and it’s a project that he seems immensely proud of. When it premieres on June 29th on Nowness, it’s more than likely worth watching.