NR: Does the influence for your work come as a result of direct experience, or an unconscious culmination of different encounters?

Adébayo Bolaji: Definitely the latter, and I don’t try to analyse the encounters or experience; if anything I am analysing the work when I’m in the act of painting. It’s after the work is finished that I go, ‘Hey man, what is this about?’ It’s ironic because, in the act of painting, I am constructing, to which you might ask, is constructing not a conscious act? Well, it is, but I respond to shape, colour and try to feel out or listen to what the art is trying to say to me; so I am like an active observer. It’s not just aesthetic, however, it is more like philosophy. I’ve recently been reading Nietzsche’s ‘Beyond Good And Evil’. He explores the concept of trying to find truth, and the irony and contradictions of doing that: what is one using to measure this ‘truth’? So, thinking about your question again, it is both: direct experience and unconscious encounters because, arguably, the two cannot be separated.

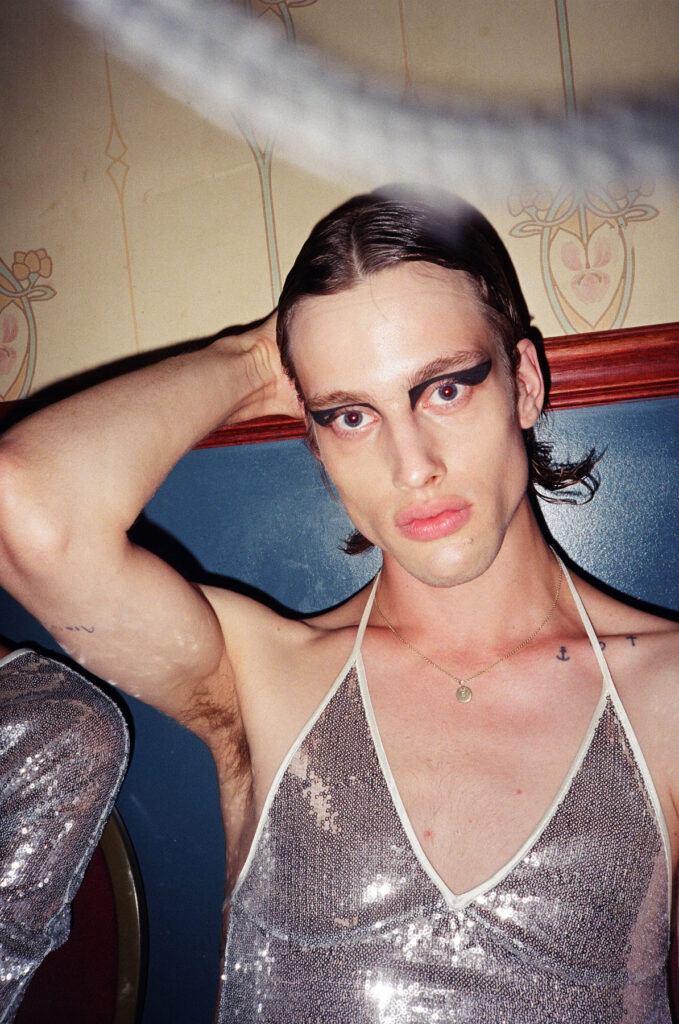

NR: How do constructions of narrative and performance shape your role as an artist who paints?

AB: We use words to understand things and put them into departments so we get a better sense of them. So, constructions of narrative and performance are words that relate to a particular knowledge of a form, and form is an image – a tangible one. I’m realising that I see things in a way that jazz might sound. If you listen to Coltrane, or even bebop, and hear how wild an instrument like the tenor sax sounds against all the other sounds, it can be seen as sounding crazy, that it isn’t music, it’s self-indulgent. To me, this chaos is organised chaos; it’s very free in its expression, but it is still complimentary. I see how these elements all connect and feed into each other organically. The construction of narrative, at least in drama, revolves around a protagonist, who wants something they do not have. The story is about trying to get or be this thing, and the drama is someone or thing standing in their way. This has to have high stakes: if the protagonist fails, they stand to lose a lot, making the story exciting and keeping the audience connected til the end. A performance is about self-awareness, and the use of one’s space, pace, timing, energy and listening. I try to express all these things in a single line on a canvas or page. In one line, there is emotion; speed; pressure; spatial awareness; and positioning. Narrative has shaped my mind to know how to place figures, shapes, it’s even shaped how I approach how to hang a show.

NR: For your Rituals of Colour show at Public Gallery, you reconstructed your studio space: how important is your studio to your practise?

AB: Very. One of my favourite artists, Francis Bacon, said of his studio that images form out of the chaos – his studio was a giant, fantastic mess. I loved that. Your space, how it is, affects the mind and body a lot. Even if you walk into a restaurant, its ambience, how the waiters are dressed, how clean the windows are – that’s already preparing you psychologically for what the food might taste like! Again, it goes back to this idea of how things are connected. This also means how much time I spend in and out of my studio; your surroundings are just as important. Music and light in my space is important too, it’s all a part of it.

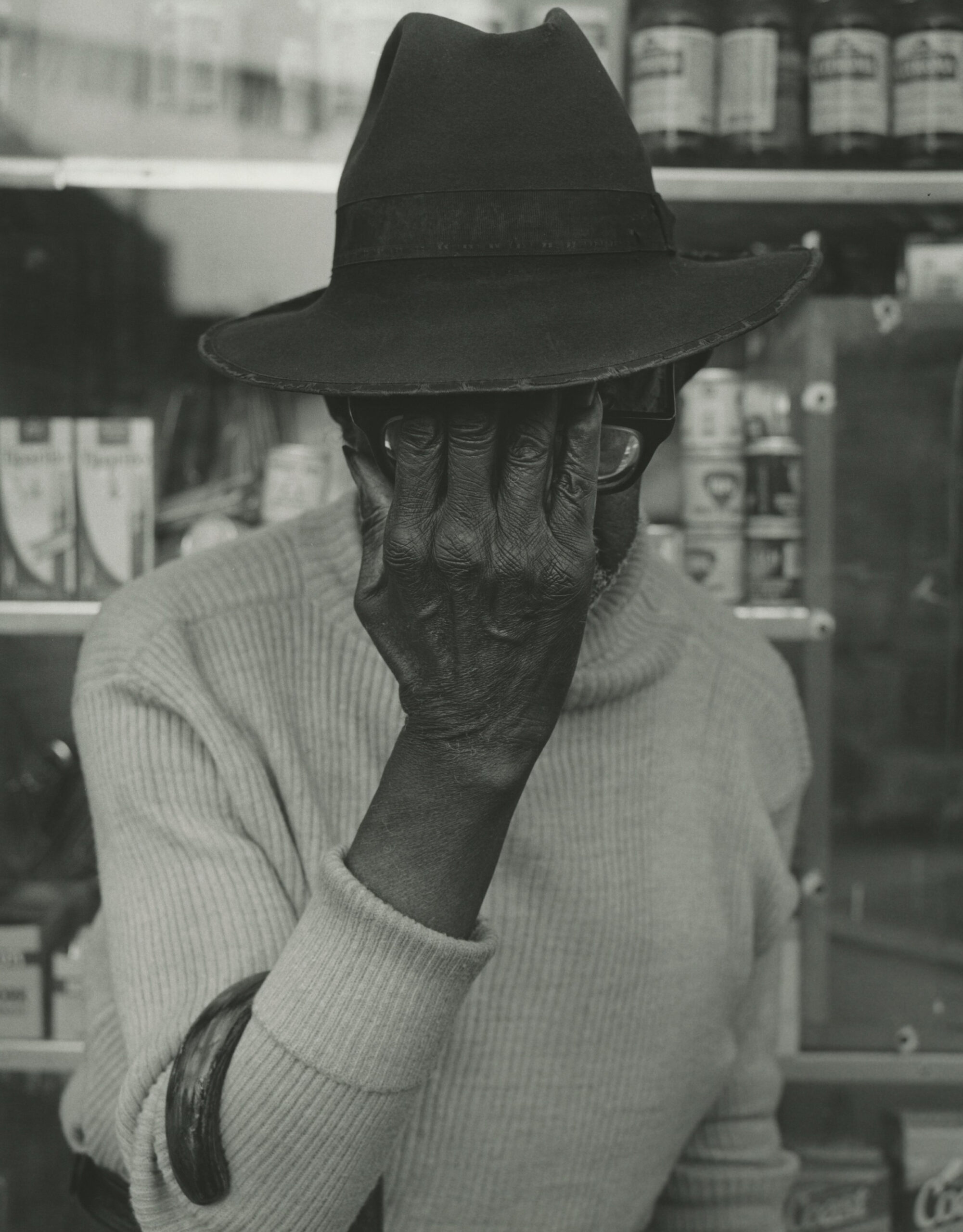

NR: You have said that you decided to hand write the captions for the work on show at Rituals of Colour in order to reveal to the viewer the tangibility of the work, something which, to me, evokes the ideas of Brechtian theatre; is there something in that?

AB: Yes. I like people to be engaged and ask ‘why?’ The Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effect), makes people aware of their existence, it reminds them that they are alive and not just walking zombies, and to be critical viewers.

That said, I’m not against the escape. I use a lot of colour and expression in the work, and anything that is seemingly emotional allows for a sense of wonder and escape.

In the exhibition, I didn’t just write the titles, I added poetical or odd sayings that were connected to the paintings. To me this was more interesting than just naming the painting and it’s materials. There is way too much ‘should’ in the gallery, when, ironically, we are supposedly encouraging the artist to free themselves from the presupposed, and to introduce us to the new.

NR: Do you place particular importance in the support material you use in your paintings, like, for instance, the 1950s ironing board used for The Agreement?

AB: Not intrinsically. I don’t even know if I always like a piece when it is finished so, sometimes these support materials are a way of trying out new things, and sometimes they are conceptual. The ironing board was definitely conceptual, so it has theoretical importance but, at other times, it’s purely because I like the way it looks or want to try something new. I think there is a danger in trying to push an idea, I think it stops us really listening to ourselves and our planet. I do feel that real connection occurs through honestly, not when trying to push an idea just for the sake of it. I like artists like Purvis Young, who take the idea of using what is accessible to them, a collage in a way, and as a kind of ‘by any means necessary’. I really gravitate to this kind of work, because it sticks to you in a visceral way, makes you want to go and create as well because it ignites the body, not just the mind. However, technically speaking, the foundation of any material is very important and can affect the outcome of the work, it actually allows for the freedom that comes later, so in that sense the support material has intrinsic value from a technical and aesthetic point of view.

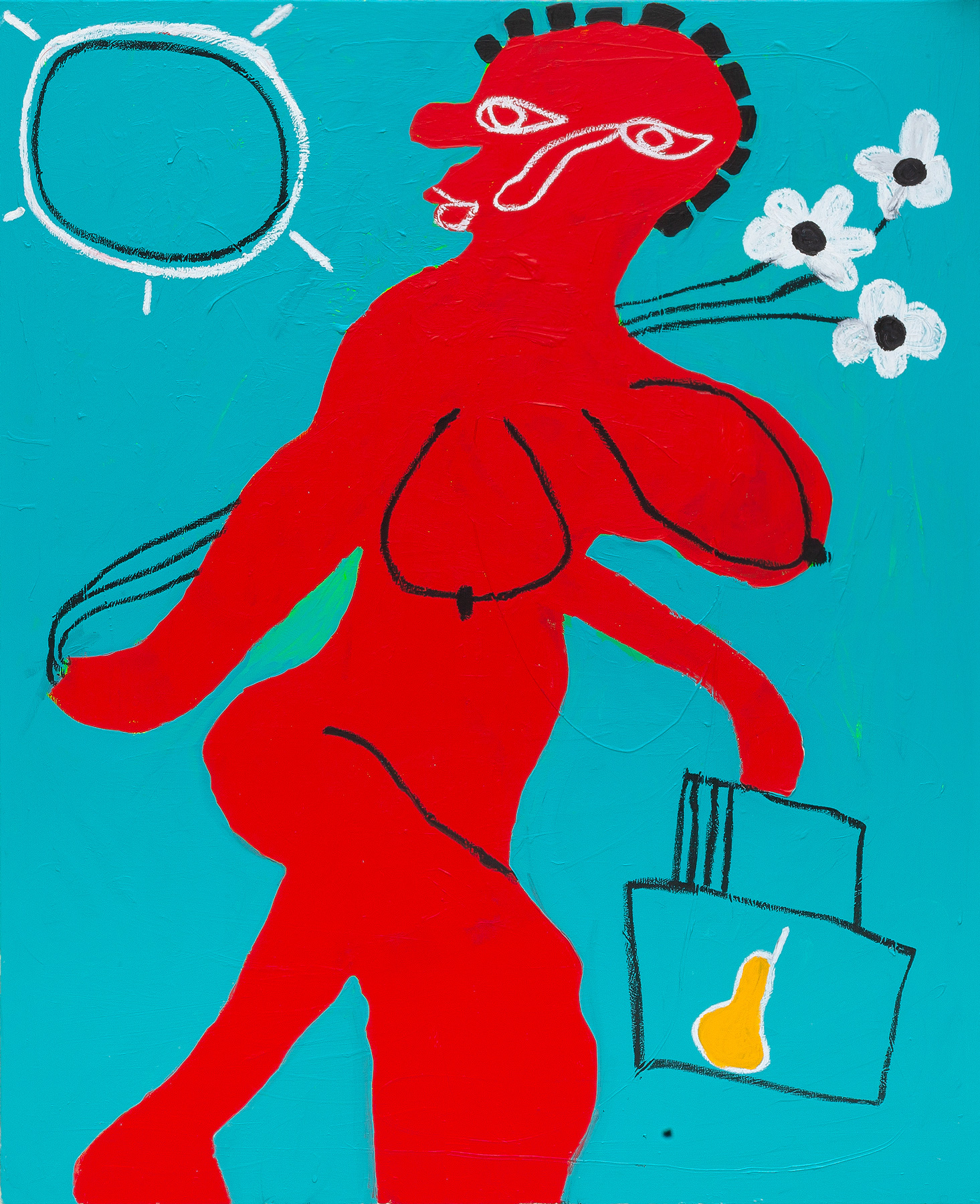

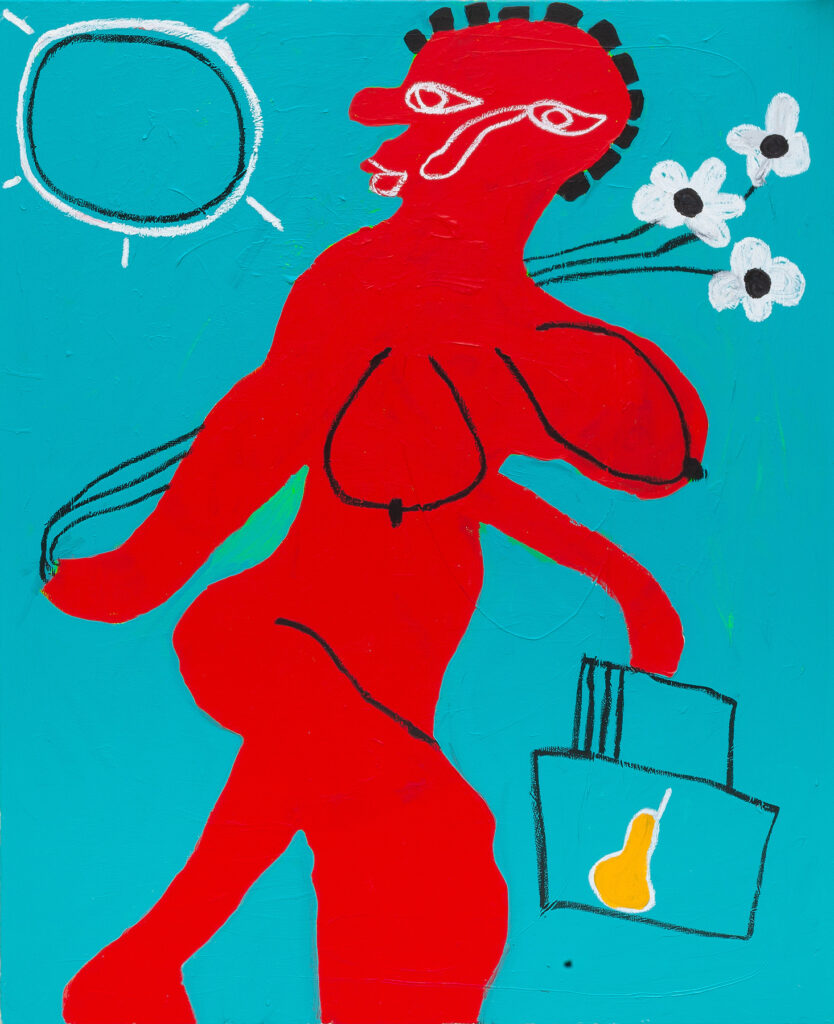

NR: What inspires the choice of colour in your work – is its significance predetermined, or something more flexible?

AB: Never predetermined. I may feel like I want to pick up blue, because that’s what I am seeing, but I go and lay down a red – like I’m translating a colour with another colour. I am led by colour a lot, even if it is the absence of it. There are painters like Bob Thompson who used colour in a magnetic way. Then you have [Egon] Schiele, whose use of colour is mind-blowing because it is there, in the midst of the absence of visual. Or, classical painters like Peter Paul Rubens, who was very brave with colour in the context of his time. I find painters like this inspirational, but I also look to fashion designers: they understand colour better than most people. Colour is more powerful than we realise. Like music, it has its own sound and voice.