Rain Room is perhaps your most well-known work, but which of your other works was the most exciting to work on?

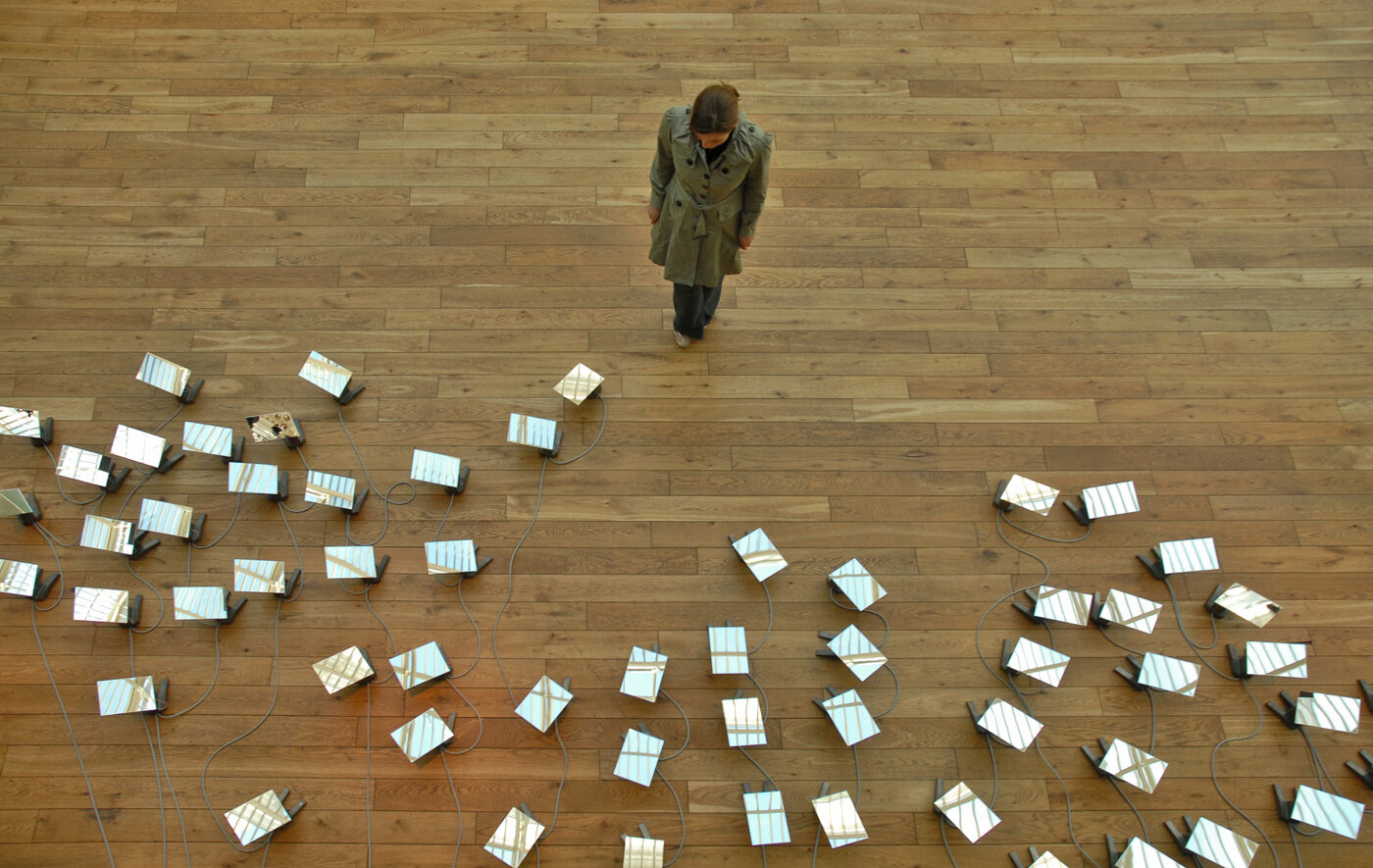

Audience (2008) was certainly a game-changer for us; it integrated several research directions that had been previously isolated: it looks at our emotional reaction to simulated life forms, it recognises body-in-space, and it starts to animate a more architectural sphere.

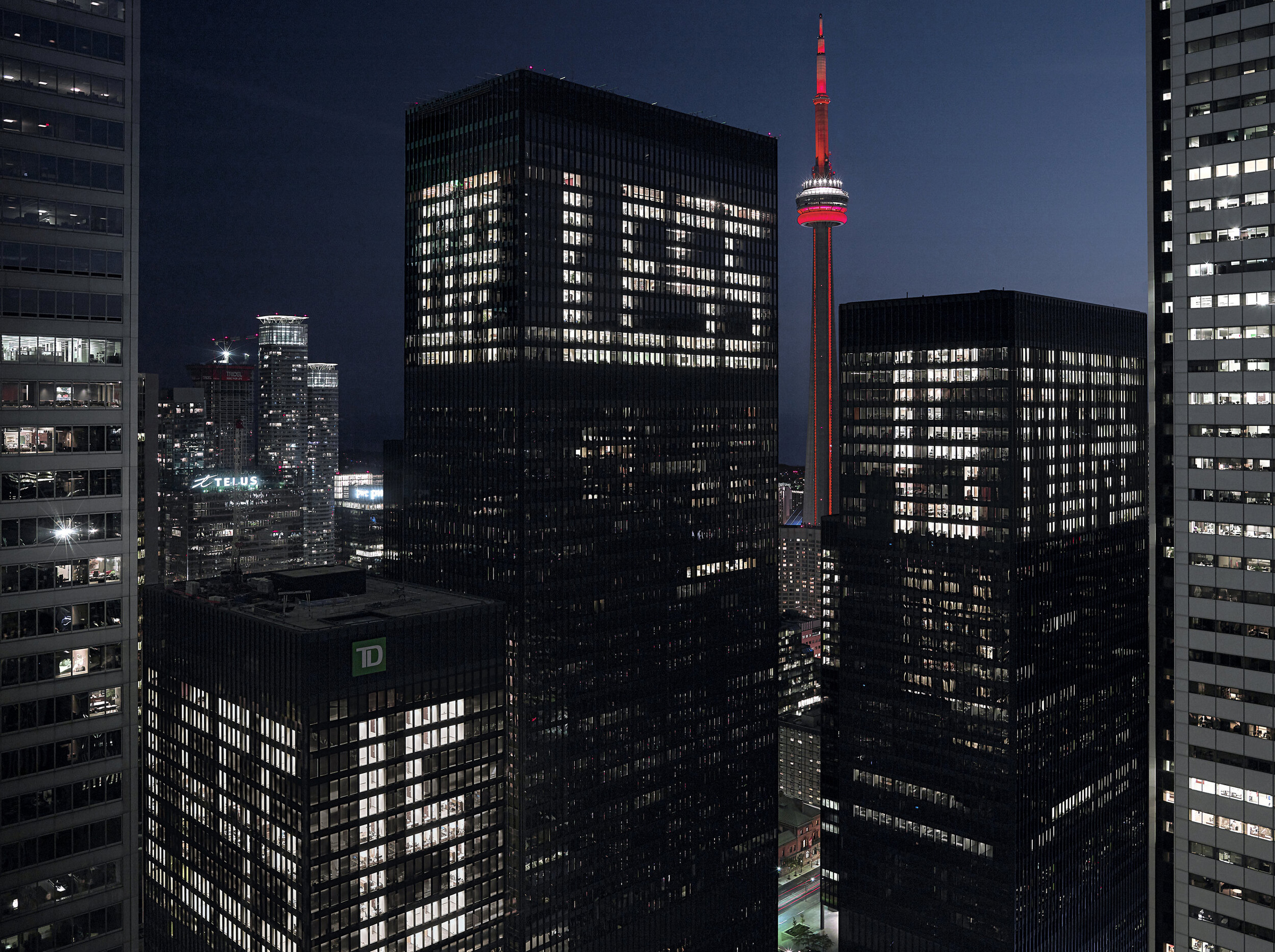

On the other end of the spectrum, we are enjoying working on Body / Light (2021), which is bringing an augmented and time-based elements into an immersive form of engagement.

Lastly, we’re in the pre-production stage/creation phase for a number of new bodies of work; while the pandemic has certainly been a huge challenge, it did allow space for deepening our experimentation with ideas, processes and technologies.

Are there any new technologies are you particularly interested in incorporating into your art practice?

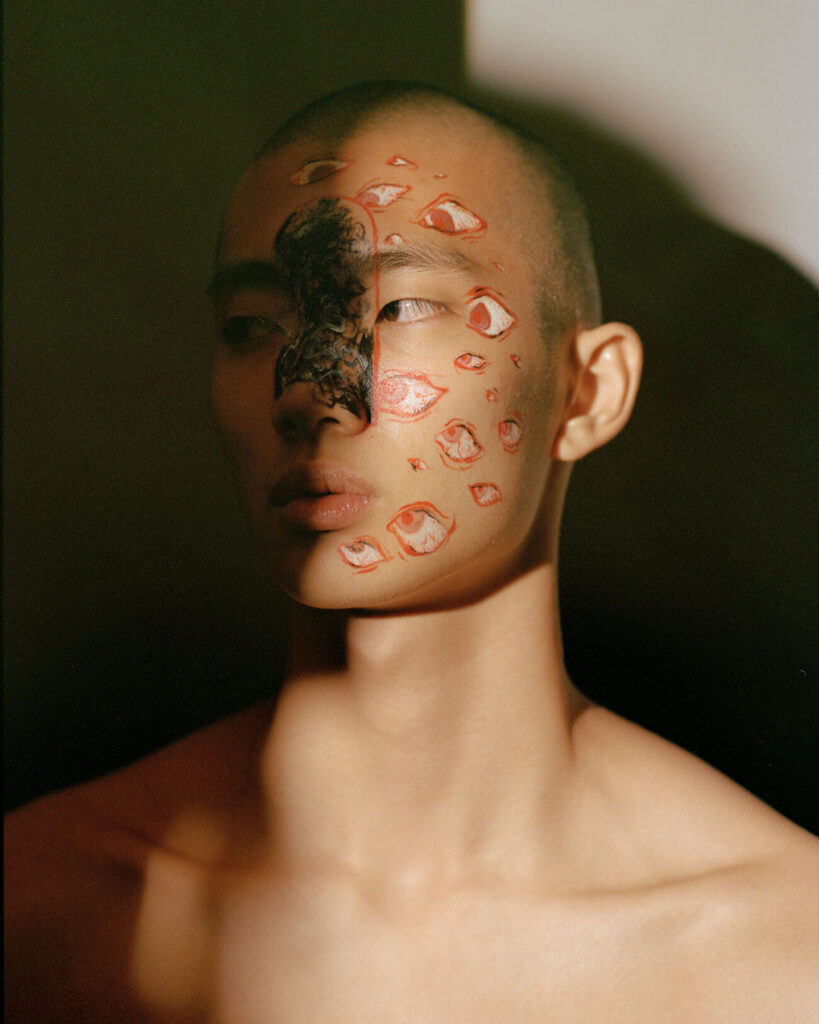

Any technology that supports us in expressing ourselves in a language that everybody can understand is of interest to us…so we don’t really have any preferences. There are however various (diverse) areas of science that we’re paying a lot of attention to, such as different areas of decision making research, developments in machine learning, some obscure branches of behavioural science, cognitive neuroscience (focus on distributed forms of cognition), Kinaesthetic learning et al.

What do you think it is about interactive and immersive art that makes it so universally popular? Do you think peoples’ shortening attention spans due to the influx of information they receive each day from their phones will necessitate even more engaging works in the future?

There’s an analogue, physical component to engaging with a sculpture in a space that cannot (yet) be met by screen-based forms of engagement. Maybe humans are still designed to feel safe in a real, physical space where the known rules apply or at least most of them. So that’s why we continue to seek out and share real, physical experiences.

You have stated you are interested in examining our ‘automated future’, how do you think technology, particularly AI, will influence your lives in the future, specifically in the art world?

It looks like we’re increasingly surrounding ourselves with machines and processes that are designed to ‘read’ us, draw their own conclusions and then respond to us accordingly. All – as with most advancements in the past – to make our lives easier (predictive text actually suggested ‘easier’ after I typed ‘lives’ just now!) and safer.

The issue is that we’re not entirely compatible with those kinds of transactions; we are not wired to fully grasp the consequences of our actions and thus one could see us getting into all sorts of trouble, existential & comical alike. Questions re the transfer of agency (i.e. can an algorithm be an artist?), distributed creation processes and algorithmically curated experiences are probably some of the topics that we’ll see flaring up some more soon in the art world. Not to speak of entire macroeconomic ecosystems that are emerging (NFT’s) and likely here to stay.