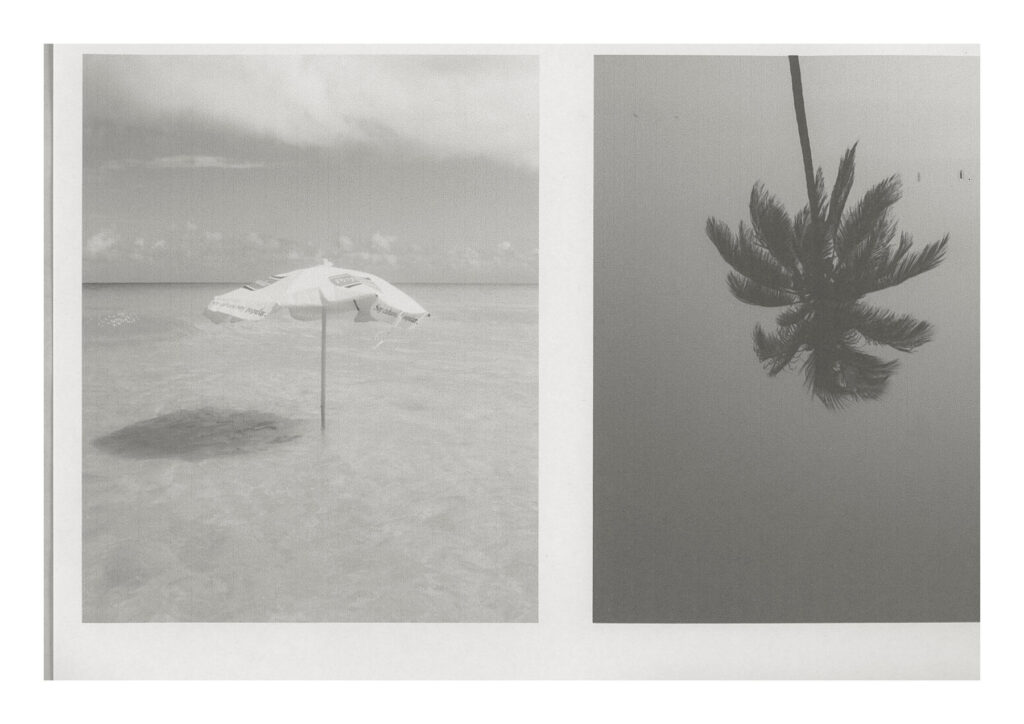

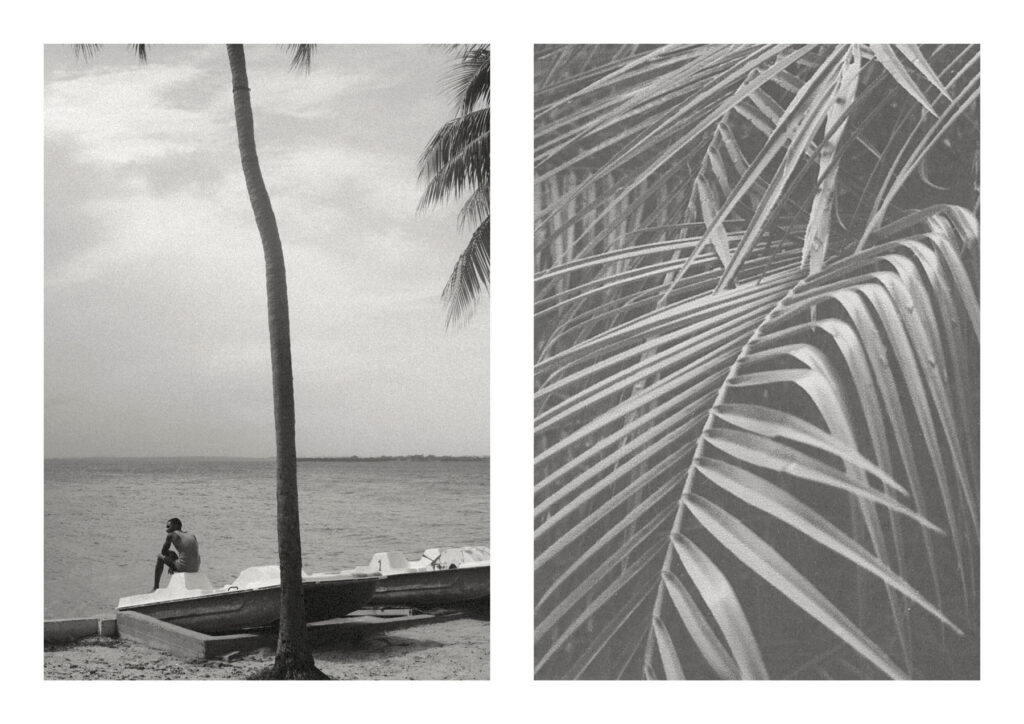

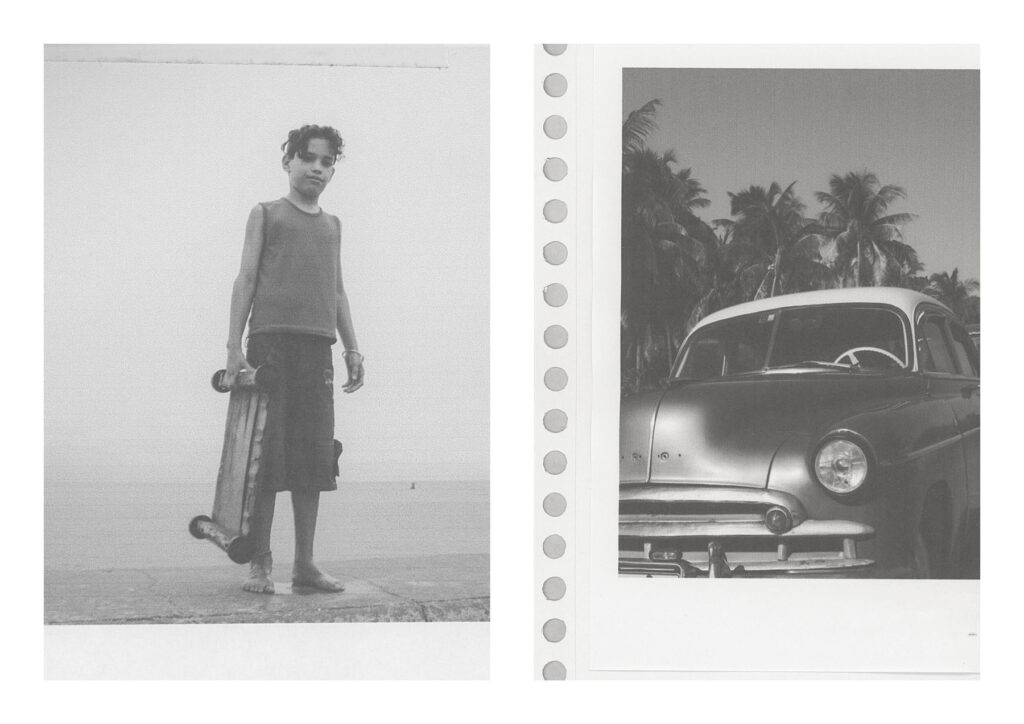

Cuba

Credits

Víctor Bensusi currently lives in Madrid working as a freelance photographer and director.

www.instagram.com/bensusi

www.bensusi.com

Credits

Víctor Bensusi currently lives in Madrid working as a freelance photographer and director.

www.instagram.com/bensusi

www.bensusi.com

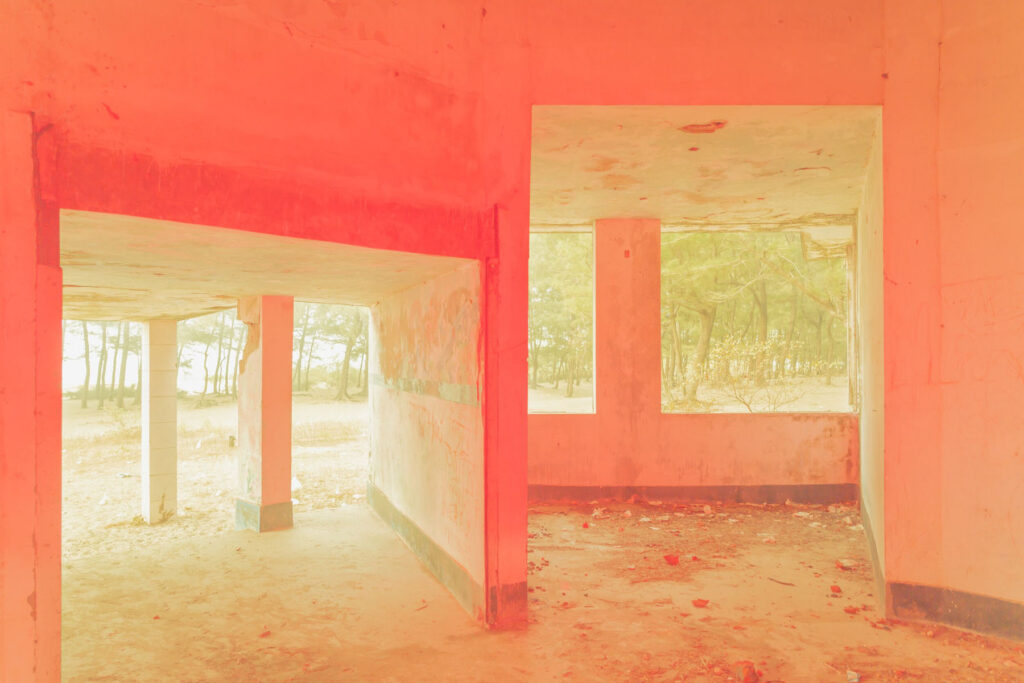

COX’S BAZAAR, Bangladesh — Cox’s Bazaar, a beach town in Bangladesh is in the midst of human and environmental interventions. Being a major tourist destination, the place is literally a sandbox of excessive commercialisation and unstructured infrastructural growth. At the same time, there is also a growing concern of rising sea level and climate change. Amidst these issues, there is a futuristic possibility of developing a beach culture in this part of the world.

Cox’s Bizarre is a metaphysical exploration of these complexities of the place, an unstructured fantasyland built on top of rising environmental concern.

CAHUL DISTRICT, MOLDOVA — This project was started as an assignment from the British publishing house FUEL.

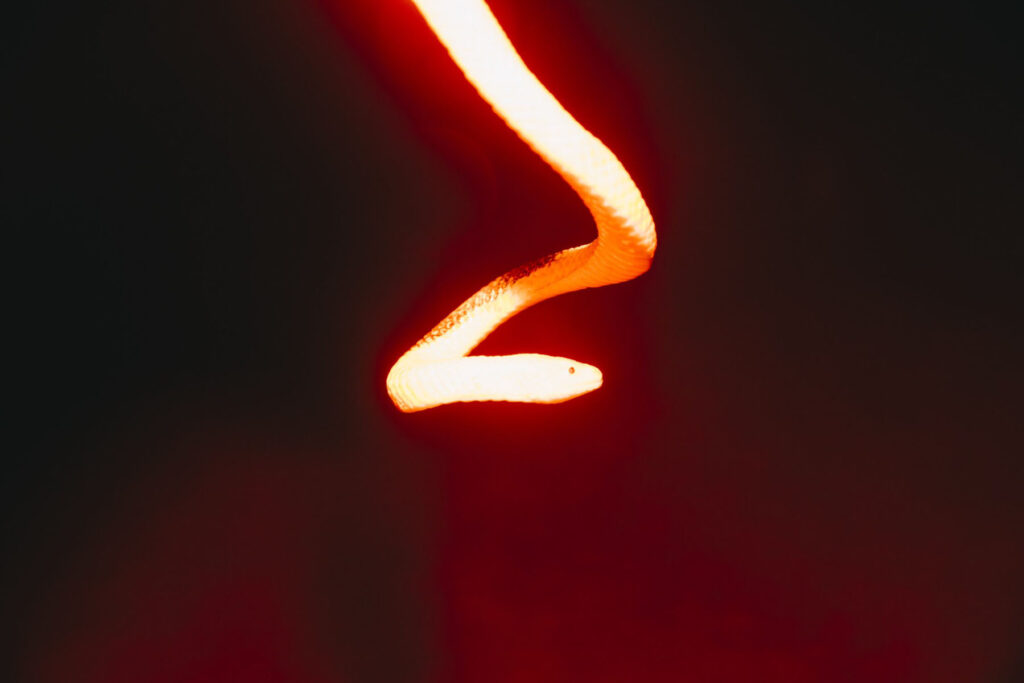

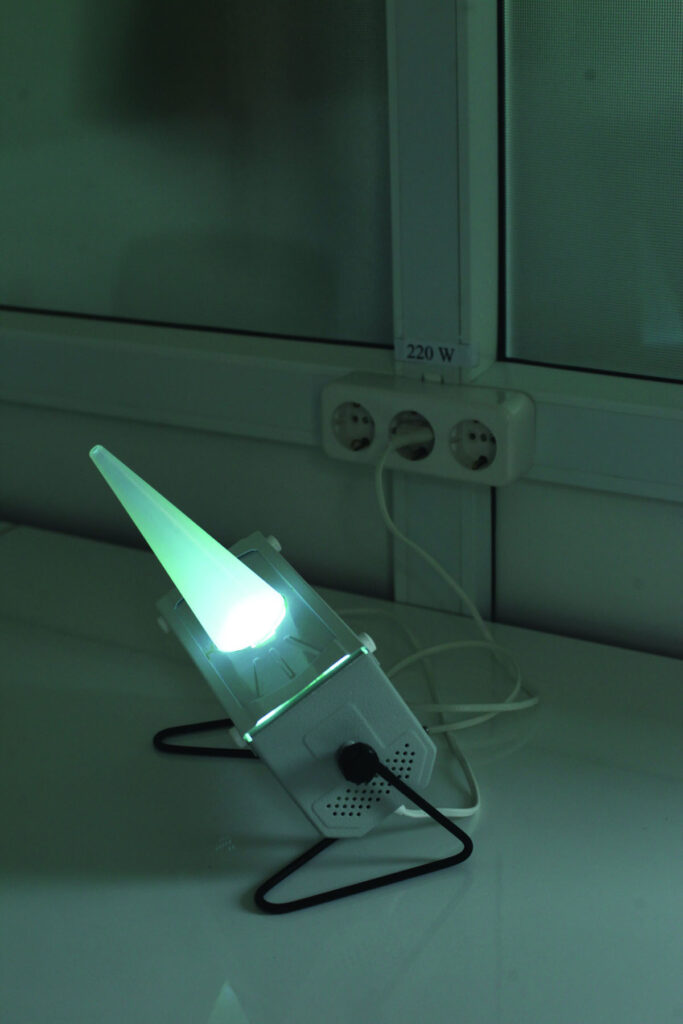

I went to Moldavia and Latvia to photograph soviet style sanatoriums with its inner life, exotic medical treatment, strange food, soviet architecture and beautiful surroundings.One day I found people doing their exercise therapy. At that moment people seemed to me so fragile and so serious that I wanted to show how helpless we are not only in front of the face of death but as life as well. It was the beginning of my own story. Photographing people on treatment, I focused on our cruel physicality, imperfection of human body, unavoidable aging, loneliness and vulnerability of human being. It is also about believing in miraculous healing with leeches, ultraviolet light, underwater massage and oxygen cocktails.

Credits

From the book Holidays in Soviet Sanatoriums for Maryam Omidi, published by FUEL.

www.olyaivanova.com

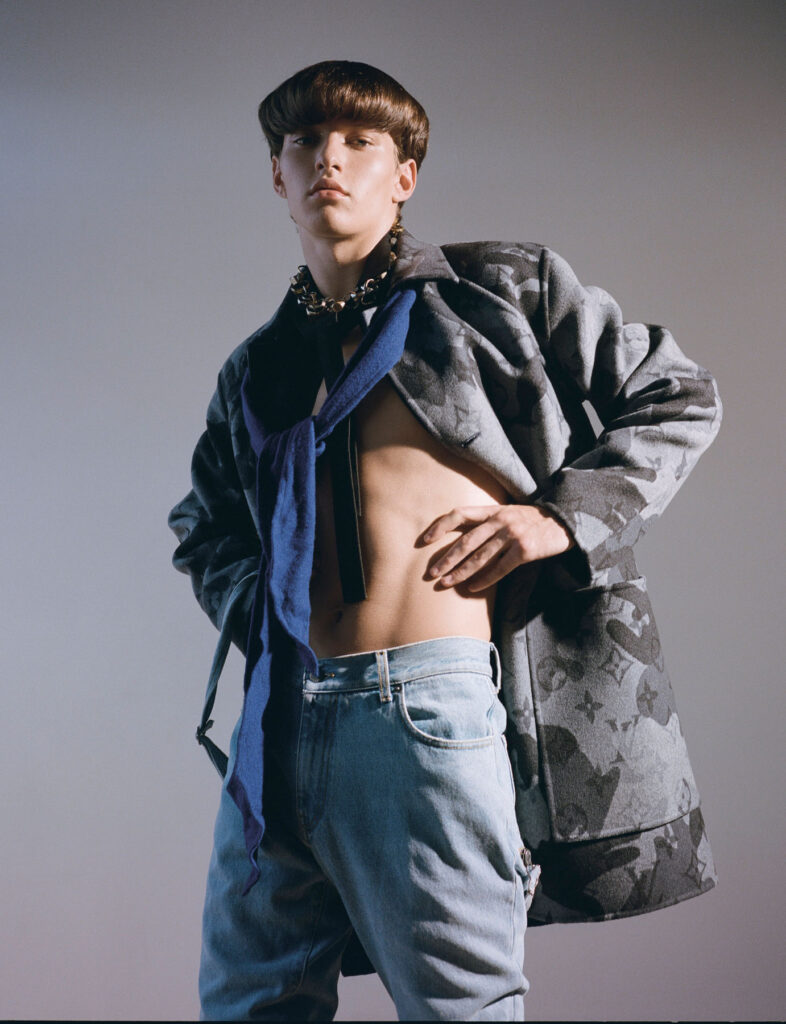

Team

Photography · BRENT CHUA

Fashion · JUNGLE LIN

Editors · NIMA HABIBZADEH and JADE REMOVILLE

Hair and Make-Up · TAKANORI SHIMURA

Model · JADEN CONNELLY at IMG

Designers

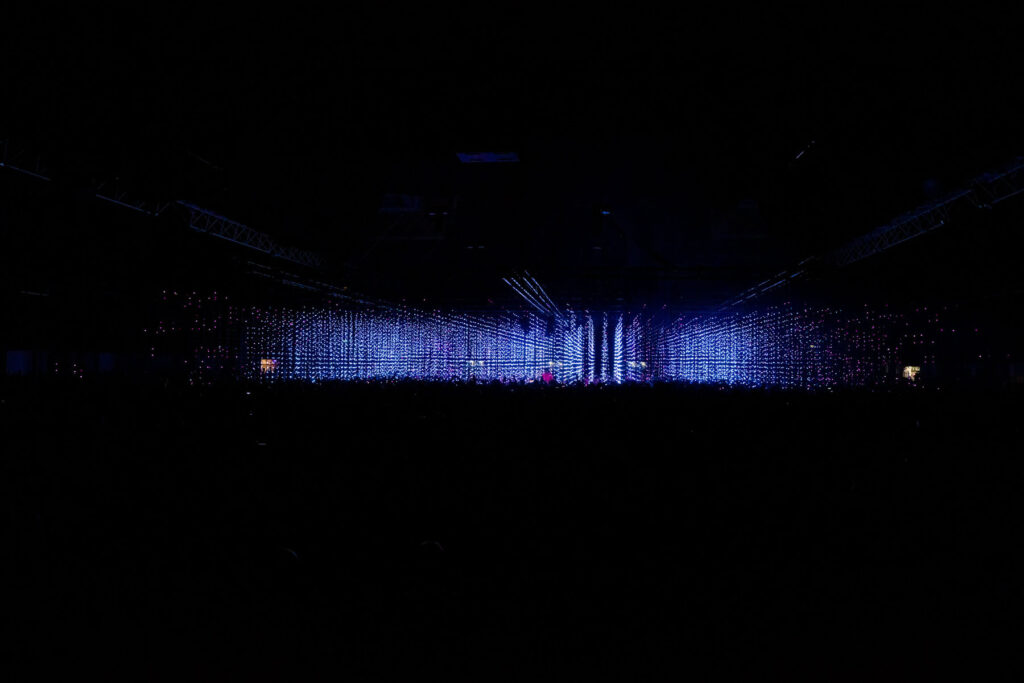

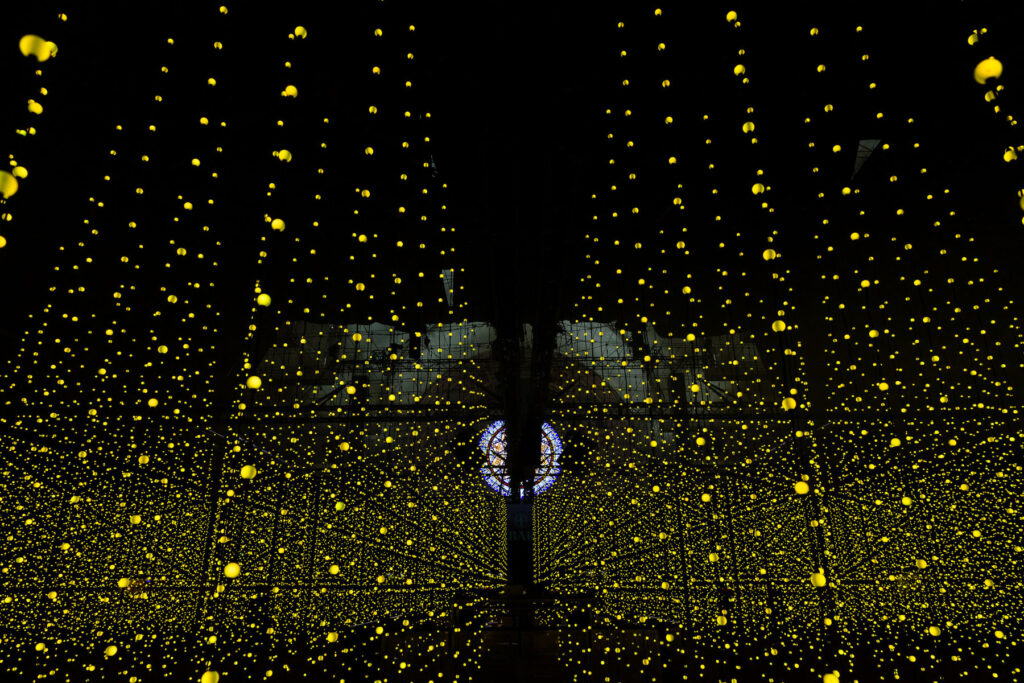

If you saw, or heard about, Four Tet’s string of dates at London’s Alexandra Palace last year, you’ll be familiar with the light installation that immersed the crowd for the duration of each show. The group behind this feat is Squidsoup, whose work for Burning Man in 2018 and again in 2019, you will likely have seen, like those Four Tet performances, via social media – if not in real life. Characteristic of Squidsoup’s work are visually and sensorially-arresting experiences, where light and digital art responds to physical space and the people who populate it. Yet, behind and beyond the ethereal qualities of Squidsoup’s work lies the technological and logistical realities that makes an installation of over 40,000 individual lights amongst a crowd of 10,000 people (as was the case for Four Tet’s Alexandra Palace shows) possible. Formed in 1997 by the artist and designer, Anthony Rowe, Squidsoup defines itself as an ‘open group of collaborators’ working across (digital) art, design, technology and research. Alongside Anthony and the group’s six core members, there is a team of full-time and part-time staff, freelancers, as well as a warehouse, workshop, studio space, and fabrication facilities. With Squidsoup’s trajectory corresponding more-or-less alongside the major digital advancements of the past 20 years, the group has been continually successful in bringing technological innovations into the realm of art, performance and the material world.

As Anthony explains to NR over email, without the level of digital connectivity we experience today (such as 5G, the Internet of Things and “ever smaller processor sizes”), much of Squidsoup’s work would not be possible. Being able to adapt and change alongside the progression of technology and the digital realm is only one part of Squidsoup’s story, however. As Anthony notes, “interesting ideas are normally [those] pushing the boundaries of what is reasonably possible – either in terms of materials, software, engineering or logistics. Originality and novelty are highly-prized attributes in this kind of work; to achieve that, you need to be pushing the boundaries.” Now, as Covid-19 alters the ways in which we experience and use digital and physical space – perhaps, in some ways, irreversibly – Squidsoup are learning to adapt again. In response to the pandemic, the group have unveiled Songs of Collective Isolation, a piece which reconceptualises the larger, immersive installations that Squidsoup are known for on a more intimate, or individual, scale. “This is not a piece for massive social interaction,” Anthony outlines – rather, it’s a “contrast, a parallel track to our larger public artworks.” And as much as it is evidence of Squidsoup’s ability to respond and react to the world that their work is shaped by, it’s not the end of those bigger works: “Perhaps it is also in part a memento to those larger projects, and a sign of hope that those days will soon return.”

How did the idea for Songs of Collective Isolation come to fruition, and how will this piece work in real-life settings?

Songs for Collective Isolation emerged from a series of explorations, looking at the possibilities of minimal, slow-paced sound- and light-scapes, free from the need to think about practicalities such as people flow, visitor experience and dwell time. We wanted to create a piece that would slowly draw you in, using natural and unadorned sounds, and exploring the effects of layering multiple iterations of the same sound, each from its own speaker suspended in space. The result is a raw set of sampled sounds (a violin recorded very close up, played by Giles Francis) that gains depth and breadth when played independently through multiple speakers – it fills out; becoming an orchestra, rich and deep, from such simple beginnings. We also saw a parallel with the current global situation – social distancing, lockdowns and so on. The potential of what we can achieve together, and the fragility of isolation that we were suddenly confronted with, seem to resonate within the piece. The piece starts with a solo note that, only after quite a while, begins to build in strength and variety.

The work uses a hardware and software system we have been developing in-house for the past few years, that we call ‘AudioWave’. It is the same system that was used at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona to create a piece called Murmuration (2019-20) that comprised over 700 individual speakers and orbs of light, suggesting the movement of light and energy around the outside of that building. It builds on earlier iterations such as Wave at Salisbury Cathedral, Desert Wave at Burning Man and Canal Convergence, and Bloom, first commissioned for Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. This piece is much smaller, more intimate, with just 18 light/speaker orbs. It is designed to be seen in quiet, private or controlled spaces – again resonating with the current situation.

The footage of Where There is Light is poignant to watch; How was the work, with light responding to the stories of refugees and asylum seekers, developed?

From the outset our goal was to create an abstract space in which people could listen to some real stories from real people; refugees within their midst in Gloucester. It was also important, I think, that this was done in a positive way, as part of a non-lecturing experience. And finally, we wanted to bring attention to the amazing work of GARAS (Gloucester Action for Refugees and Asylum Seekers). An opportunity arose to show the work in Gloucester Cathedral, and we worked with Everyman Theatre and Music Works, two local organisations, to put the piece together.

Visually, we wanted each of the four testimonies to have a different feel, a different visual reference. And finally, there is a musical crescendo where we took the opportunity to let rip with the lights a little! The project was a collaboration with a refugee organisation local to the studio in Gloucestershire UK called GARAS. We all hear stories of refugees, but the enormity of their ordeals is so outside of our experience, that attempts to represent their lives becomes mired in the discussion of guilt, responsibility, economics and race.

How did Squidsoup’s work with Four Tet come about?

Having created indoor and outdoor versions of a project called Submergence and shown it numerous times in various types of spaces and events, we felt that the approach of the work, using a walkthrough 3D array of points of light (controlled in real time) to create the impression of movement and presence in a shared physical space, could be adapted for use elsewhere, in particular in live stage performance. In 2015, Kieran Hebden of Four Tet was finishing the album Morning/Evening, that was, for him, something of a stylistic departure consisting of two long, meandering, Indian-inflected tracks, and was wondering about a live set. A mutual friend connected us.

“The plan from the start was to search out serendipities; happy coincidences where two working processes coincide, creating – hopefully – more than the sum of their parts.”

The first shows (Manchester International Festival, Sydney Opera House, Roundhouse) had a conventional stage layout, with our volume of lights behind Kieran on stage. For a gig at the ICA in London in 2016, Kieran suggested placing himself in the centre of the room, on a low riser, in the middle of the lights. The audience, also within the installation, surrounded him, effectively breaking down the wall between audience and performer – placing them in the same space and creating a different kind of audience experience. A hybrid of performance and installation; a blurring of boundaries between stage and audience space; plus, of course, the mixing of physical and digital inherent to the original idea of the work. The ICA had an audience of 300, as did National Sawdust and Hollywood Forever, US, which we then expanded to some 6-to-700 at the Village Underground (Shoreditch, London, 2018), and eventually the 9,000 plus at Alexandra Palace. Upcoming events in Berlin and the USA are currently on hold due to the COVID situation.

Has the collaboration with Four Tet changed the possibilities of experiencing live music?

New possibilities for experiencing live music are emerging in many ways, as technology improves and becomes more available. None of what we do would be possible without a myriad of technical innovations. We have been pushing the relationship between performer and audience, performance and immersive installation experience as described above, aiming to deliver new types of experience. But we are not alone in doing this. The collaboration with Four Tet is an example of a creative partnership looking for new ways to engage audiences and expand performance – to create novel kinds of experiences. In one key sense, this has been a rare opportunity. The relationship Four Tet has with his audience is unique: they are cerebral, with high expectations, but they do seem up for new things. Not every audience can be trusted to treat the work with the physical respect it needs: the LED strands dangle in among the audience – a different audience could easily pull and break them.

What informs the ways that Squidsoup responds to different environments?

Most of our larger commissions are awarded, so we respond creatively to a specific space or cultural brief, and we also use these commission as an opportunity to advance our own agendas and work. In effect, this means that we use the space, location, community/audience, and any brief we are presented with as a canvas, and the systems and technical approaches we have developed are the paint (or medium) to create a new piece. Enlightenment, a project we installed in the North Porch of Salisbury Cathedral, was informed and inspired by the symbolic importance of the cathedral, its history and presence, and was also a response to the nature of the space. At a practical level, we needed to take into account people flow into the building, and to consider how the light and sound bounced off walls, and so on; the affordances of the location. The Polaris work at Burning Man was almost the opposite in terms of approach and experience. The first time we did it, we had no idea what we were getting into; we just liked the idea of an LED cube driving around the desert. We were invited out by Cyberia, one of the camps at Burning Man, to give it a go using an ex-army truck. What could possibly go wrong?

“It was a baptism by fire, and the answer is pretty much everything went wrong (generators failing, dust getting literally everywhere), but we learnt what needed to be done for kit to survive out there.”

We were lucky to be invited to return the following year, where we both re-ran the Polaris project and were also commissioned to create a new work for Burning Man 2019: Desert Wave.

It’s fascinating to see Squidsoup’s progression from the early works to some of the large-scale bespoke commissions. Is there a direct connection between these earlier pieces with the present day?

Definitely. Our work has always been about immersion – working to create beguiling trance-like experiences and making the tech an invisible enabler, rather than a prominent component. Visually, our works have moved away from using screens, as the screen is a boundary; a barrier between the viewer and what they are looking at. We wanted to break down that barrier, either by placing the viewer inside the content, as with VR, or by letting the media spread into our shared, physical world. For us, VR felt too lonely an experience, where you leave this world behind, so we looked for more hybrid approaches, eventually landing on the various approaches using arrays of lights (and sound) in physical, walkthrough, shared spaces.

As our work has developed, it has become more abstract. This is partly due to the nature of the media we now use, but it also feels right for us, as it allows for quite a primal, visceral form of engagement. It also allows each person experiencing the work to decide what it means for them. That, in itself, is an interactive and creative process. What is consistent throughout our work is a will to remove the technology from one’s conscious experience. We’re not pretending it’s not there (our work is quite technologically ambitious), but we don’t want people feeling that they are engaging directly with ‘computers’. This is partly because they are a means to an end, not a focus in themselves in our work, but we have noticed that people change their approach when confronted with digital/binary decisions. They start to think about how it all works, which is absolutely not what we are looking for.

“We want people to suspend disbelief, to go with it and experience the work with all their senses, rather than their intellect.”

What can people learn from Squidsoup’s interdisciplinary approach to combining technology and research with music and art?

Interdisciplinarity is increasingly necessary in our work, but I’m not sure that we actually see it that way. We see it more as collaboration between people with different skills, as we need a range of skills and expertise in order to make real our artistic visions. Learning advanced computer, materials, robotics, music, design and architectural skills, and so on, takes time and, if you’re not working with a trained professional, there will be a lot of learning by trial and error. Even when you are using a trained professional, we often end up asking them to do things that are out of their comfort zone anyway – so trial and error, and iteration, are the order of the day. Connected with this is communication. We often work remotely, even more so these days, by necessity due to current movement and social distancing restrictions, so getting an idea across clearly but accurately is vital when working with people from various disciplines. Although our projects generally start with a fairly clear concept and idea, there needs to be a degree of pragmatism involved during the development phase. Some aspects of an idea may be impossible, or better approaches may be uncovered along the way. Being able to see these and work around or with them when they arise, is crucial – and also down to communication. The flip side to that is that it can also be tempting to dilute an idea for the sake of practical expediency. Any changes of direction are carefully thought through to ensure that the core concept is not compromised.

Squidsoup is described as something that can ‘be experienced online […] and in shared spaces’; how do you anticipate the different ways in which participants might engage with the work, either in real life or via online footage?

In mid-2020, the variety of ways that people can engage with our work are significantly compromised by social distancing, travel restrictions and other knock-ons from the current pandemic. Our best-known works are experiential physical spaces, in galleries or outdoors at festivals and other events. But we do also create permanent exhibitions, and smaller artworks that straddle the area between installation and art object. Currently this is a main focus; to make smaller works that can be experienced in private and smaller, more controlled, public spaces. Although our works have been shown many times, the world is a large place and the most effective way to speak to global audiences is through the web and social media. We have not made a web-based artwork for many years, but we try to document our work in an honest and truthful way, so that people who can’t actually make it to an installation can still get some understanding of what the works entail. However, most of the online content associated with our work is generated by visitors. Social media users have been kind – many of our projects are very selfie-friendly. There is a definite irony there, as one of our stated aims (as mentioned above) was to move away from screen-based experiences to physical ones. And yet here we are, with many more people knowing our work from digital content than from encounters with the physical work.

Designers

Their work move between different languages such as sculpture, installation, kinetic art and painting. The modus operandi: to constitute itself as a subject, and from its mechanic materiality, to point to transcendence, to mysticism and to the unknown. Encompassing installation, drawing, painting, sculpture, performance, sound and video, Lolo & Sosaku’s wide-ranging practice explores the capacity of creating new meanings through the association of the objects, the surroundings and the spectator. Taking inspirations from ancient Greek sculptures, from Dada and Bauhaus School to Jean Tinguely, Alexander Calder and Jean Dubuffet, Lolo & Sosaku soon altered the traditional artistic practice concentrating on the possibilities inherent in the materials they used often metal, wood, glass, incorporating music and sound. Electronic music is certainly the highlight of their inspiration as a complex language translated into sound installations and sculpture compositions. Shapes, lines, materials and sounds are assembled together into motion sculptures that perform taking their own voice in an unpredictable continuous transformation Exploring many artistic horizons and redefining boundaries, their interest is the energy and the hidden forces that guide life in our technological age.

Lolo, Sosaku! You guys. Truly beautiful to meet you last week. So, lots of things were said and I thought of some recap key ideas that stayed floating around. I would start with SONAR, in which you just performed a few days ago.

Given the present pandemic context, you have just been part of the (first ever) virtual edition of SONAR, where you live streamed from your studio in L’Hospitalet.

How did this situation feel? How did you conceive producing this piece to fit an iPhone screen? (Modern times…)

Lolo: We felt in a way alienated while completely connected at the same time. Is the digital streaming behind this or is it a more global thing related to the current situation? Maybe both, yet we are anxious to be back to physical exhibition dynamics.

Sosaku: Visualizing our work through phone screens was conceived as an amplified version of our usual visualization mediums or supports, always having in mind that the spectator completes the artwork, even from the other side of the screen.

L: Our piece Concert for four pianos is an audio piece interpreted by non thinking machines installed in four pianos, they are sound sculptures that generate different textures and audible rithms. With this sounds we composed a sound piece with Sergio Caballero and thats the piece we presented in Sonar, putting up three shows for a reduced audience from our studio and a concert that was showcased for the whole world from Sonar’s live plataform, it was a great experience.

We understand our artwork as something that happens between a gap in what we conceive as the “present”, where concepts of space and time are no longer a unified continuum and act as separated entities.

S: We feel comfortable working in this temporal space.

L: With the years, we have created our own reality, as Arca coined it the last time he was in the studio. “A world within a world”.

Do you have hopes that our future may shift back into a less technological reality, in a sort of resistance act, or do you encourage the exploration of technology in this sense?

L: We are living in really particular times, exposed to constant sudden changes, in an accelerated way. The Anthropocene, the current geological time according to Paul Crutzen, is characterized by the visible and signicative influence of human behaviour in the planet… for some theorics it goes back to the industrial revolution… inexorably this age would evolve into the Post- Anthropocene, which, in conversations with Maike Moncayo, we differ in how it will take place, given that for her it will be the communion of human-machine-nature, forging a new ecosystem of renewable energies and a way back to the natural equilibrium of the holocene. Our vision is a bit darker given that we believe that we will evolve to a kind of machine – human symbiotic being, to survive climatic changes and death, where nature will be in a second plane or extinguish, given that it wont be necessary.

When we met, we talked about your artwork’s translation from the physical, tangible world into the two dimensional language of video or photography.

You mentioned a particular experience with Disco, where the audience thought you were presenting a 3D render, when actually there was an actual disc and a whole physical effort behind it.

Did this experience transform how you conceive future artworks?

S: To forge Disco, a huge human physical effort was necessary. Lots of months of hard work interpolated with unplanned difficulties. It was a great adventure, and I was working sick for the whole of the production.

L: Disco is a site specific project that works in dialogue with MentalStones, a permanent installation by Tito Diaz, which is situated in an olive field in the Delta del Ebro area, far away from civilisation. To our surprise, when we published the first images of the project, we received several reactions which interpreted that the artwork was a 3D render. We had put so much into it that the final piece looked artificial, like a render…

Even though Disco exists in the intersection between sculpture, land art and video art, we had never imagined that the audience would interpret it as a digital artwork.

S: We think imagination is sometimes digital.

L: It is a constant transformation… the digital looks for the organic, the real mutates into a digital language. We are exposed and immersed in a constant digitalization of everything, I wonder if Disc would have actually been a digital render, would it be real?

As sensible subjects, what interests would you say you pursue or dig on through your practice?

L: We see autonomous intentions in the behaviour of some of the machines we create, which escapes any logic understanding, as if they acquired a soul-condition, or something like it.

S: When we did the theater piece we had various press conferences… conventionally, actors also assist to this conferences so we took with us Tipo P, one of our sculptures, which was the protagonist of our piece. I was with him for many days, travelling by metro and taxi to different places, and a really close nexus evolved.

L: Tipo P did really bad in the first interviews.. as if he were nervous. He changed attitude once he was in front of cameras… thank god he did really good in the actual performances.

S: Yes, he’s a really good actor.

Being that you come from so far apart (literally, Japan-Argentina) the fact that you have found each other and created this artistic communion, to say, feels like a magical encounter, your artwork, this synergic creative act, like an alchemic process. Do you believe in chance?

Have you ever thought about how your paths could have shifted if you had not ran into each other?

S: We’re really close friends and we sort of like the same stuff.

L: The first time we met (early 2004) we could barely communicate because we practically didn’t speak english… and naturally we started creating stuff and working together… we developed our own language and work methodology which imprints itself in all of our work.

S: Now we work in the same ways as in the begining, but in bigger projects.

Lolo: Nowadays when I think of that first encounter, in like how this unexpected chain of events brought us together, I feel very grateful.

S: Yes, if I think about that I feel as if an exterior force had joined us in some way.

L: Maybe that is chance, two independent processes that converge… Lucrecia, you were asking if we believed in chance, we do believe and we implement it in lots of our artworks, maybe the most evident one would be Panting Machines.

S: We build machines that have as an objective to paint or draw, and though we are very present during the process, they paint what they autonomously desire to paint, and when there are more than one of them, lots of times they collide, change paths and generate new lines and shapes, mixing their traces.

L: There’s a whole narrative revealed in chance.

This issue of NR has the concept of Change as its main trigger. It is obviously a word that resounds in all of us given the pandemic context, in any of its multiple consequences. If you would be able to propose, within a utopian scenario, activities or rules for a different society… what would you suggest, if anything? All valid. And… calling on utopia, would you recommend any readings, movies, or tracks that have triggered your imagination, your conception of life or reality?

S: Create a new civilization, without violence, where everyone has access to everything.

L: In the conversation we had before this interview, we really liked something you asked regarding the spaces we use to install our artworks, which are generally abandoned spaces or spaces in which our artworks establish dialogue or modify them, you were asking if we had thought of building an entirely new space that would not only host our pieces but be an intentional enviroment for them. We could do the excercise of replying to this question with the creation of a utopic social space, a place where there are no physical limits, where anything you can imagine is possible.

I’d recommend the amazing documentary “L ́homme a mangé la terre”, by Jean- Robert Viallet

S: Yes, I’d say also the last book by Yuichi Yokoyama “New engineering”.

Credits

www.vimeo.com/loloandsosaku

www.instagram.com/loloysosaku

www.loloysosaku.com

Lolo and Sosaku’s work has been exhibited and performed, amongst others, at

Museo Reina Sofia (Madrid, Spain), MACBA Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (Barcelona, Spain), PSA Museum Power Station of Art (Shanghai, China), MIS Museu da Imagem e do Som (São Paulo, Brasil), Fundation Gaspar (Barcelona, Spain), Fundação Casa França Brasil (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil), Sónar (Barcelona, Spain), Matadero (Madrid, Spain), Palace of Culture (Iasi, Romania), MAVA Museo de Arte en Vidrio de Alcorcón (Alcorcón, Spain), O Art Center (Shanghai, China), Luis Adelantado Gallery (Valencia, Spain) and Instituto Cervantes (Milan, Italy).

Designers

The acclaimed street photographer, Jamel Shabazz, first picked up a camera as a teenager at school in Red Hook, Brooklyn, in the mid-1970s, set upon making images of his friends and classmates. Shabazz was no stranger to the medium; his father was a professional photographer whose collection of photobooks were made available to his son. Black in White America (1968) by the photojournalist Leonard Freed, was one such book that had a profound impact on the young Shabazz.

After a stint in Germany with the US Army in his late teens, he returned to find the New York he left behind in a very different state of mind. Racial tensions and violence were on the rise, and crack cocaine was just beginning to seep into the foundations of daily life. In that moment, the impression that had been made on Shabazz by photographers, like Freed and Gordon Parks, became clear, as he turned his camera onto the people that he’d grown up around in Brooklyn and New York. By making images of the people that weren’t usually photographed, Shabazz sought to heal growing divisions – countering animosity by taking the time to talk to the people he stopped with his camera; giving them the chance to express, and be, themselves. Shabazz refers to himself as a conscious photographer, using his practice to enrich and improve the lives of those around him. And as he explains over email, this has made him acutely aware of his ‘personal responsibility as an image-maker, [creating] images that shed light [on the communities he documented], while combatting the negative stereotypes that were often being presented in the media.’

There remains a critical importance to the images Shabazz made from the 1970s through to the 1980s, of a city, and its communities, lost to racist policy-making and rampant gentrification; in 2020, it’s not difficult to make the case for why. But for all the social injustice that underpins Shabazz’s work, there’s something else of equal importance that the photographer has long been commended for. A casual glance at the photographer’s work and it becomes clear that the subjects he turns his camera on have one thing in common: style. In that moment that the photographer clicks the shutter, his subject become all that matters in the world, regardless of what’s going on behind the scenes. ‘Time and motion is frozen,’ Shabazz notes; and the poses, the gestures and the dress of the people he captures become take centre stage. As he explains of the editing process, Shabazz looks for ‘images that speak to the soul, inspire joy, or simply provoke thought and reflection.’

You refer to your work as being the positive medicine to counterbalance negative stereotypes of the Black community; how do you feel that you have been able to achieve this?

There has been much grief and anger since the start of the Covid-19 crisis, as well as the endless incidents of racial injustice and police misconduct. My daily postings on my various social media feeds have provided me with a great space to share images that bring joy and reflection to the viewer. I receive numerous responses on a daily basis to these posts, from people around the globe, writing to tell me that it brings them joy and hope when my images appear on their feeds. It is in that process that,

“I feel that I am able to counter negative stereotypes, while also providing a form of visual medicine and relief from the daily stress of life in 2020.”

How did becoming a street photographer change your relationship with the cityscapes of New York?

During my stint in the military overseas in Europe in the late 1970s for three years, I read Claude Brown’s book ‘Manchild in the Promised Land’. His depictions of, and personal experience navigating through, New York, intrigued me and informed my interest in exploring the vast landscape of my city. As a result, I was inspired to come home and venture out into the city to document what I saw, and that is exactly what I did upon my return, in 1980. During the first half of that year, I travelled throughout the five boroughs, seeing first-hand the beauty and diversity of one of the greatest cities in the world, all while documenting it with my camera.

In 2018, you received the Gordon Parks Foundation Award. How did it feel to be recognized as continuing his legacy? Did that recognition change how you perceive your work?

Receiving the Gordon Parks Foundation Award for documentary photography was one of the highlights of my career. The accolade served as an indicator that the work I have been doing for so many years had been recognized. For me, the award was a symbolic being passed on to continue to work in the spirit of Gordon Parks; to use my camera as a weapon to fight against injustice and the misrepresentation of images that harm communities of colour along with those who are struggling around the world.

The camera is your weapon of choice, but what determines the type of camera you use?

At this stage of my life, any camera that has the ability to record an image is fine with me. I generally carry a basic Fuji X100 with a fixed lens and my iPhone. The creative eye is more important than the camera.

In an interview from last year for Afropunk, you mentioned your aspirations about being a curator; what does this role involve for you and how do you intend to realise this?

“During my travels, I have met countless aspiring photographers who have created amazing imagery, but never had an opportunity to showcase their work in an art gallery.”

Having had my own work in a gallery, I felt it was my responsibility to aid those photographers I’d met, to help them gain traction. In 2008, I got such an opportunity, when Danny Simmons asked me to curate a group show in his space at Corridor Gallery in Brooklyn, New York. I was honoured by the invitation, and gathered around 20 photographers for a show that was called ‘Positivity’ – the theme being centred on positive imagery and how artists can come together using the global language of art to make a difference in the world. The exhibition was a success and helped set the stage for the next generation of image makers. Just last year, I was granted another opportunity to curate an exhibition – this time at Photoville in Brooklyn. I reached out to my good friend and comrade Laylah Amatullah, who served as co-curator, and we produced an exhibition entitled ‘Perspectives’. That show consisted of 12 gifted documentary photographers from diverse communities, all with important work and voices. The images that were selected dealt with issues ranging from Albinism to various protests. The objective of the exhibition, like the previous one I curated, was to bring new visions onto the scene whilst also addressing pressing social issues. Presently, I am working with a curator in London to bring the concept there, with the inclusion of 12 European artists that share similar concerns.

Do you look at your photography through the context of the present day or through the eyes you took it at the time?

Considering the challenging times we are living in, where life as we once knew it has changed, I find myself revisiting a lot of my earlier images and reflecting on a time period when life was very different. For me, there was a time before both the crack and AIDs epidemics and then the war on drugs, which opened up the flood gates to mass incarceration. As a witness who documented the early 1980s I saw a lot of hope and promise.

Your work is inherently social; how has the coronavirus pandemic affected your ability to take photographs and connect with people on the street?

When the Coronavirus hit this country, I had to re-evaluate my whole approach to the craft. Even just having to contend with wearing a mask has had some challenges, and the mandatory requirement for everyone to wear one has led me to fall back and redirect my energy towards revisiting my older work. For the past few months, I have been scanning thousands of negatives from the 1980s and 1990s, reliving moments that are long gone. That whole experience has rekindled a flame inside and brought me great joy. However, I do miss connecting with ordinary people on the streets, but today I am embracing Zoom and using that as a platform to bridge the gap and maintain some degree of normalcy during these uncertain times.

Your photographs capture people’s legacies within an image, especially those who often go without recognition or acknowledgment in society, and especially within the context of New York during the crack and AIDs epidemics. In light of the coronavirus pandemic which has disproportionately affected poorer, unprivileged communities, and also as the BLM resurgence has provoked us to recall the names of those whose lives have been taken, how do we, going forward, meaningfully capture the legacies of those who are no longer with us?

The struggle continues and we need all hands on deck like never before to be proactive in the fight for freedom, justice and equality. I am greatly concerned with, not only the future of this country, but the world itself, in these very troubling times we are living in. I also feel that the larger global artist communities must raise their voices, along with their level of creativity in order to address the ever-growing problems that are facing the world.

Photos

Credits

Photography JACK JOHNSTONE

Fashion NIMA HABIBZADEH and JADE REMOVILLE

Hair SHUNSUKE MEGURO

Make-Up SEUNGHEE YOO

Models LUARD from Premier Model Management and LARA from Nevs

All clothes featured from TOGA including an exclusive coat from the TOGA x BARBOUR collaboration

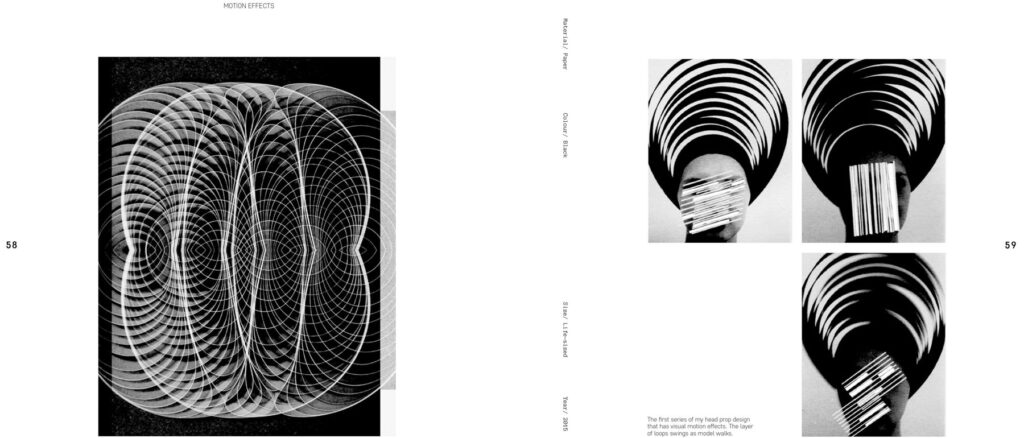

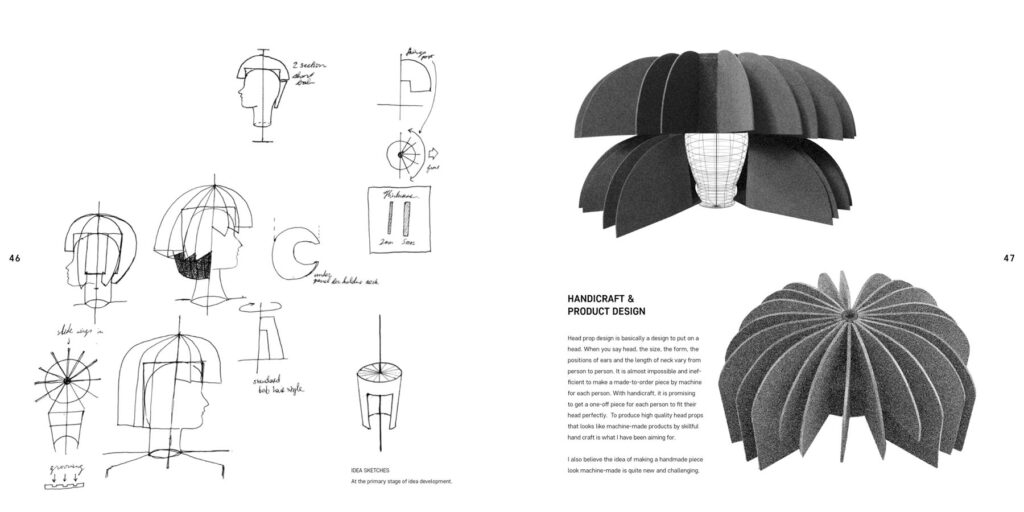

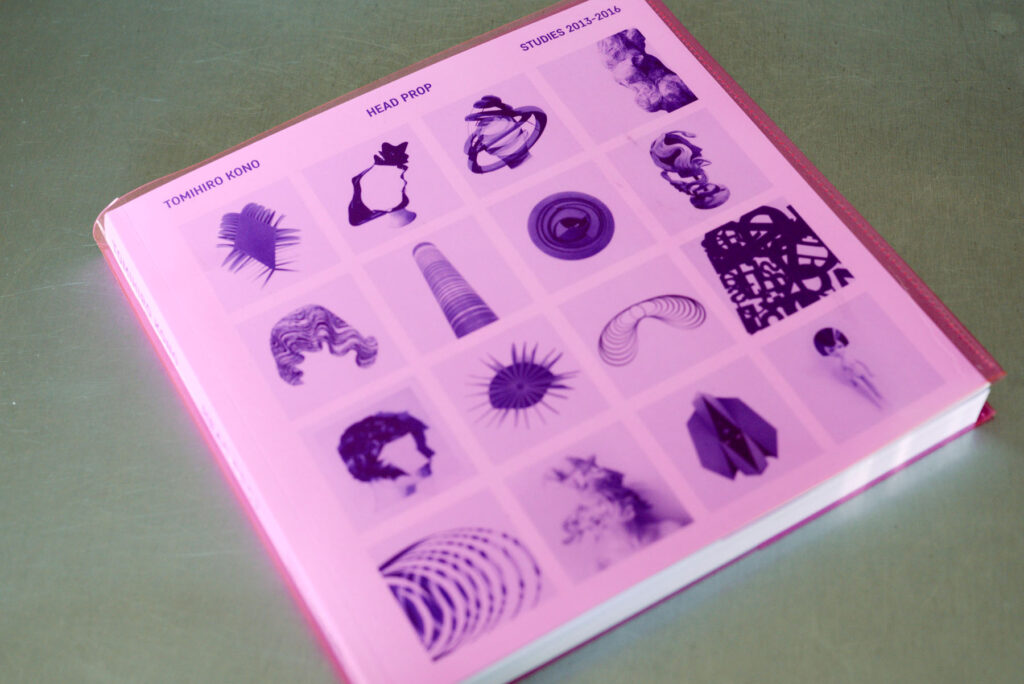

Tomihiro Kono, a hair stylist and head props creator, currently based in New York City, is best know for his outstanding work with designers such as Jil Sander and Junya Watanabe. His launch of his own book ‘Head Prop’ is a ‘documentation of distinctive head prop work produced’ by himself. Not only does Tomihiro produce ‘visually striking head designs’ but ‘designs that focus on functionality in the beauty of form’. Kono has grown to become the master of a genre he created from himself.

I understand that your career started in Japan, where you worked as a hair stylist. But how did the idea of creating wigs and head props appear in the first place? What was the starting point for you?

I started my career as a hairdresser in Osaka, where I studied basic hair skills. Four years later I had gotten seriously obsessed with geometric haircut techniques and decided to master the method. I ended up working in a few different hair salons in Tokyo and acquired the best haircut skills. In 2017, when I branched into session styling, I moved to London. I started head props originally to satisfy my own creativity but I’ve always been obsessed with new hair and head creations. The act of hair styling and designing head props are, according to me, closely related to each other. They go hand in hand. Therefore, as a hairstylist it’s also my responsibility to keep working with hair designs in order to grow as a creative.

Was this all a part of your childhood dream or was it something you grew into as you got older?

When I was a young boy I wanted to become a veterinarian, which is quite different from what I do now. So I would definitely say that, as I got older, it was something I grew into loving. Even during the beginning of my career as a hairdresser I wasn’t dreaming about working abroad as a session stylist. I have just always been focused on doing the best I can and working hard. This is where it has taken me.

From a creative point of view, what was it like to grow up in Japan? Did the Japanese culture become a strong source of inspiration to you or was it just an influential cultural background?

Personally, I always got more inspired by the Western cultures. But when I moved to London I started to find more understanding of my own background. I think that the Japanese culture used to be something I would just take for granted. After moving to London, I created a Geisha inspired portrait series. This is a classic example of our distinctive heritage, which I’m proud of.

Many successful people have said that having access to a big city is always an important part of your career. After living in both London and New York, two of the largest fashion capitals in the world, what do you think is the most significant difference between the designs you’ve produced in each city? In what way did the city affect your work?

I believe that my first choice of city was the right one. London has a great hair culture, especially the avant-garde style with its young creative- and punk influential spirit. It’s a city where people really appreciate originality. For me,

“working in London was a mix of crazy dark, romantic goth and experimental design, which was very satisfying from a creative aspect.”

But I do think that New York is the best place to establish oneself. I always try to adapt my work to the city I’m in and its current fashion trends. Therefore, since I moved to Manhattan, my work has been quite clean and modern.

The line between most creative subjects and art is often very blurred. Do you consider yourself to be an artist? If so, did you always feel like one or was there a significant moment in your life when you realised that you wanted to become one?

If there is one hairstylist that could be called an artist, I might be that person. But that is not how I see myself. However if I could choose, I would much rather be the only one than the best one.

By being involved in the fashion industry, you are constantly surrounded by the idea of beauty and how it should be presented, but in what and where do you personally find beauty in the world?

Personally I find beauty in the world of nature, music and old Japanese films – which I like the aesthetics in.

Working with craftsmanship and creating each design by hand must be very creativity challenging from time to time. What is currently your biggest source of inspiration? When you lose track, where do you go to find it?

At the moment, my source of inspiration comes from wigmakers around the world. That is the subject I will build my new project around. Luckily, I never feel like I “lose track” so I always just keep moving.

What motivates you to grow and do better?

I motivate myself to be original at all times.

A lot of people tend to seek comfort in hiding behind their hair, do you ever feel like your bold and fearless style comes as a shock to people? Would you say that this is a part of the purpose for you?

My designs tell a story of what I do in life, if that tends to shock people, I take it positively. I know what I have done in the past three to four years is completely different to what most other hairstylists in this industry do. I personally like both natural hair styling and over-the-top head prop design at the same time, because I feel confident in both shadowing trends and being original at the same time. Whilst working in the fashion industry, you’ll always have the choice to create a trend as well as following a trend. So if head props become something that inspires upcoming artists and they want to follow that, or even keep building on this path I have created for them, that is something that would be very interesting to me.

Have you seen any good examples of how people have adapted your creative work into their everyday lives?

Except for my friends, wearing my creations on an occasional night out,

“I never think of my head props as being used in people’s everyday lives. I see them as head art.”

What is your best piece of advice for the people who want to follow your footsteps?

Be creative and work on building your originality. If you want to be a hairstylist and make head props as well, you need to learn about the basics of hairstyling, then play with your imagination from there on. This is how I started my career and I hope that my story can be helpful for young artists who want to pursue their dreams in Fashion.

You have worked with some of the biggest names in the current fashion industry and has had your work published in the most influential magazines and online platforms in the world. Now, just a couple of weeks ago you had your very first book launch as well. Where do you see yourself going from now on?

I never really expected my first book to get so much attention! It was a big surprise for me to see that people are curious about what this book was all about. I created the concept one year ago and I haven’t changed anything since. Towards the end of the process, after having had several meetings with some very talented good publishers, I decided to publish the book myself, because I wanted to keep the creation as pure and personal as I possibly could. I consider the release of this book too both mean the end of one chapter and the beginning of a new one. What’s next for me? Well, as you go, your career establishes your style and, for now, I have a lot of wig making to do. Hair will keep me busy for a while.

Credits

‘HEAD PROP’ by Tomihiro Kono is a documentation of distinctive head prop work produced by Hair and Head Prop Artist, Tomihiro Kono from 2013-2016.

Available to buy now with pink vinyl cover exclusively at www.konomad.com

Designers

Credits

Photography Theresa Marx

Fashion Lucy Upton Prowse

Hair Abra Kennedy

Make-Up Marie Bruce

Model Simona from Storm Models

Designers