The importance of figuration

Julia Kowalska (b. 1998 Warsaw, Poland), lives and works in Warsaw, Poland, where she graduated with an MFA from the Painting Faculty at the Academy of Fine Arts in in 2022. Her work intensely interrogates the importance of figuration: beginning by looking inward, she produces paintings that exctract the physical from the subconscious, in delicately devised dreamscapes.

The result is a simulated subconscious from which ephemeral performances present themselves in the foreground, before fading again into the recesses of a restful or restless psyche.

Julia, can you tell me about your work in general? How would you describe it to someone who has never encountered it?

I engage with painting, mostly figurative, centred around the human, although there are single deviations from this. I depict figures in ambiguous states and mutual relations. Most often my focus falls on intimate and subjective experiences.

Looking at your paintings the figures always seem to be extracted from the background, an effect that is not only due to the contrast of color (light vs dark) but also to the blurred lines of the bodies, which seem to suddenly materialize in front of us like characters emerging from a foggy environment. This stems from your desire to depict a scene that is abstracted from space and time, becoming a symbolic dreamscape. Can you tell me where your fascination with the oniric stems from?

It comes from my interest in dream poetics, with the concept and aesthetics of the uncanny. I am inspired by the enigmatic quality of dreams, in which it becomes possible to have lucid and tame experiences in a way that allows them to be both familiar and strange. Dreams push the boundary between imagination and reality, from something familiar and accessible into something peculiar, striking and unexpected. These qualities allow me to explore the fluid, shifting perspectives of Self. And just as Self includes both consciousness and unconsciousness, in dreams unconsciousness comes to the fore, systematic and chaotic collide. This opposition allows for the simultaneous existance of ambivalent meaning, which remains the core of my exploration, because I believe it says the most about ourselves. No matter what I happen to be focusing my research and painting on, whether it concerns dichotomies related to the body, the complexity of relationships or the complexity of desires, the common link is always ambivalence and the tension arising from ambiguity. I love such qualities because they challenge our relationship to reality and destabilise the Self, and in this way they are the best means of realising that Self means otherness.

Your main body of work consists of paintings. You have, however, experimented with other media, specifically sculpture and installations. Can you tell me how you translate your research differently according to the distinctive techniques and materials you use?

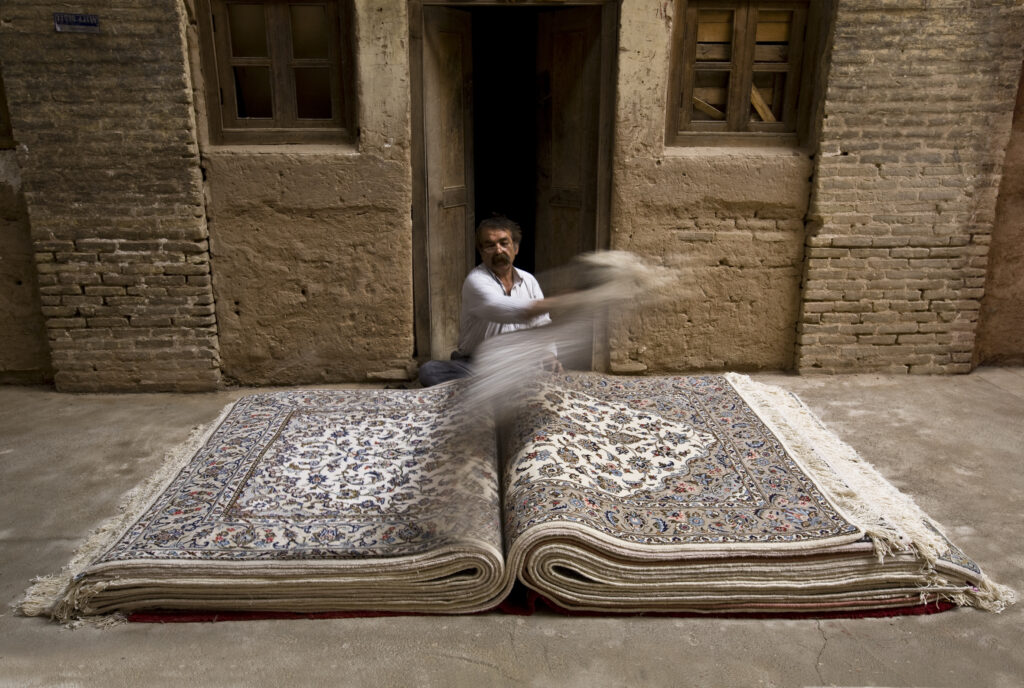

When I work with an object in space, I find it easier to think about the form abstractly, as about an isolated tissue, closer to defragmentation or hybridization. This simply shifts some conceptual emphasis. During my first solo exhibition, I experimented with wax sculptures imitating skin-like, carnal tissue. At the time, I exhibited an object – a chandelier in which I replaced the clear crystals with wax forms resembling flesh-like, meat wastes, – and an abstract sculptural form which materia and shape suggested a carnal origin, only without any indication of its interior or exterior. Both forms were associated with the body, but remained abstracted from it, unidentifiable. They could evoke associations with the abject, in places resembling subcoutenous biology causing anxiety and repulsion, while staying visually attractive, pinkish, smooth to the touch. Using a wax imitation of the body, its crafted form, I tried to find corporeality in another context, or rather, to locate it in all the contexts in which the body exists – in a kind of conflict – organically, naturally and culturally. I am currently in the process of working on my fourth solo exhibition, where I plan to juxtapose wax sculptures with painting. I think that conceptually the sculptures will similarly oscillate between meaning and divergences around the body.

In a previous interview someone asked about the way you imagine your shows, and you talked about the fact that you think of a singular work always in terms of its relationship with others. I find this very interesting, because it relates to the construction of meaning. Instead of seeing it as intrinsic to the single painting, you seem to believe that it is gradually built through a relational aspect. Could you tell me a bit more about this?

The relationship of the images is important to me and I take care to ensure that they maintain a dialogue with each other and act on each other. This works for me rather intuitively. Of course, it helps to build or complement contexts. I can duplicate certain meanings and at the same time contradict or undermine them in the next painting. This allows me to intensify, for example, the impression of confusion.

In our conversation it emerged that this belief is also translated in your actual working method: you work on multiple paintings at the same time, carrying impressions and fragments of each of them with you as you paint, therefore almost scattering traces in all of them. Is this link amongst all of your paintings something that you see once you visualize them finished, all together in a space?

Yes, more or less. When constructing an exhibition, I have all or most of the paintings in my mind and on sketches, although it is never a finished idea. A great deal happens in the process. I think that working on multiple formats at once allows for this dynamic of work, where I can navigate the relationship of paintings with each other on the fly. It’s just easier to gather thoughts and put a concept together.

This approach towards meaning and the relevance given to the relational aspect of the works stems also from the acceptance of change (and transformation), which is seen as a constitutional element of your working method. I am curious to know how you see, for example, the role of the public in relation to your work.

I do not yet have a formed view of this relationship, although I do indeed often consider the viewer and imagine the potential trajectory of the reception of my work. I deliberately work with attractive, visually pleasing figuration, using an aesthetic that may flirt with patriarchal sensibilities. Attractive, pinkish, soft bodies, often female, and nudity – subtle and erotic, not obscene – are meant to seduce with the promise of endless viewing pleasure. The image triumphs when the consuming gaze stops confused at an ambiguous detail or, questioning the initial impression, begins to presume the ambivalence of the whole scene. Perhaps in such viewing dynamics I find the potential for realizing ever-present patriarchal sentiments and clashing dichotomies related to communing with the body.

When looking at the overview of your works the blurred effect of your paintings- but also the choice of your materials, such as wax, as we already talked about – I can’t help but thinking about the non-finito. The wax sculptures of Medardo Rosso, for example, were often left unfinished or with features partially incomplete: this was a deliberate choice aimed to suggest continuity. Or, better said, possibility. Is that something you consider in your practice?

Absolutely! The susceptibility of wax to heat and to touch, this plasticity means that the sculpture is never final. The process of molding and solidifying liquid wax is easy to associate with this. Once during my studies, while forming a wax sculpture, I spontaneously recorded my hand massaging and stroking the slippery, fleshy surface of the wax, which while still warm yielded to the pressure of my touch and changed shape, just like living tissue.

To conclude, I would love to know what excites you about your research and how you see it developing in the future.

Well, I have no idea. Each exhibition results in new insights into the subjects I explore. I guess that’s what excites me the most.

Credits

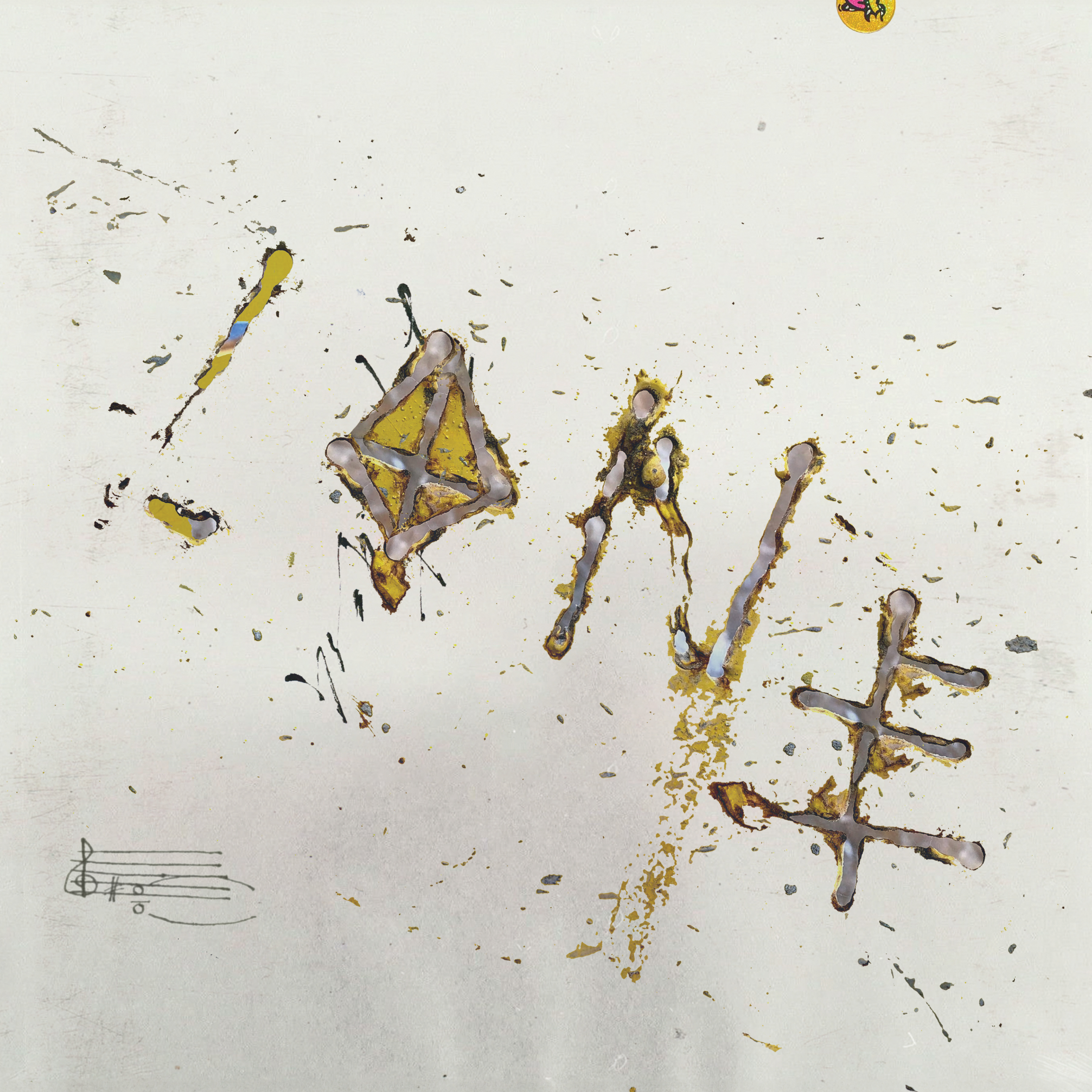

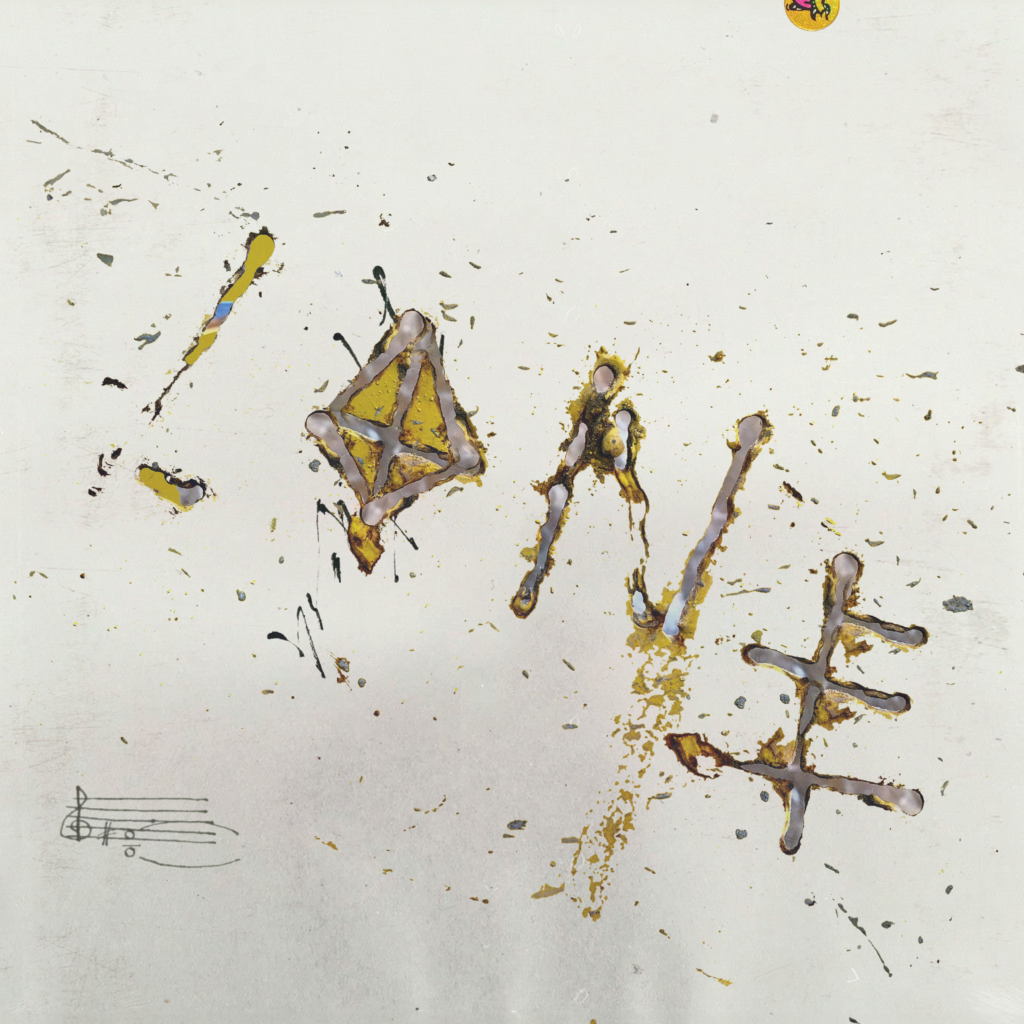

- Julia Kowalska, Milky Blind Eye, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

- Julia Kowalska, To give to eat or to allow oneself to be eaten, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

- Julia Kowalska, Flash of a smiling heart, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

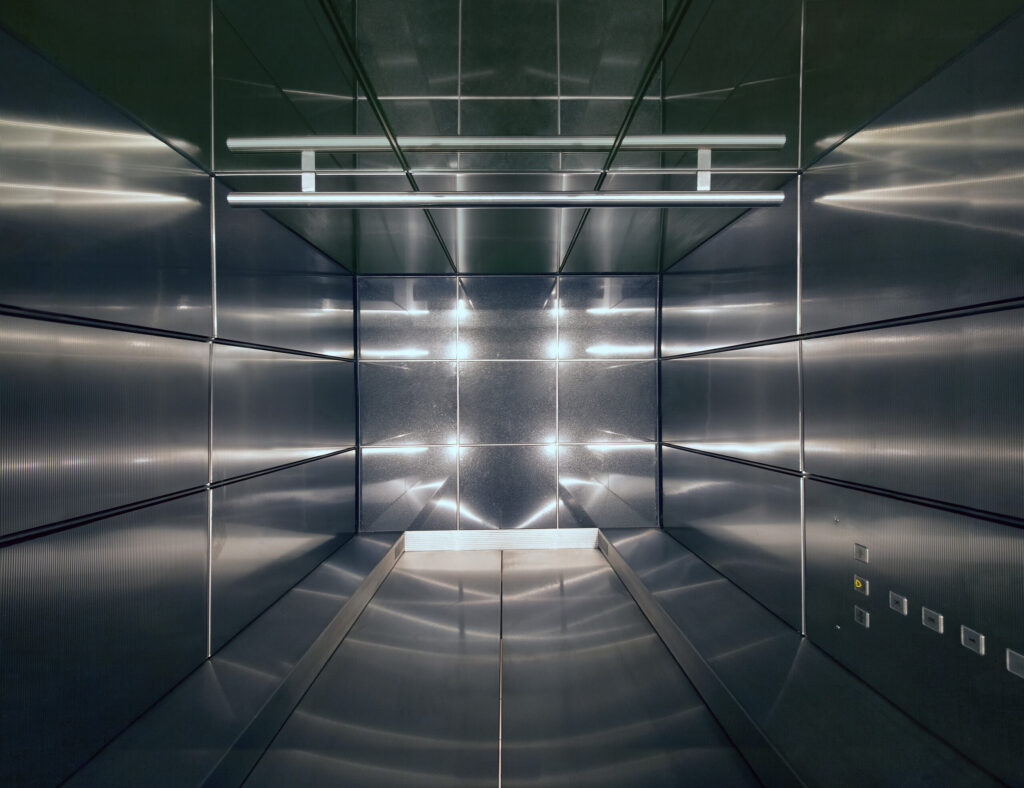

- Solo exhibition Pleasant touch, like talc powdered inside, 2022. Sklep Galeria Karowa, Warsaw, Poland. Courtesy of the artist and gallery.

- Julia Kowalska, Untitled, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

- Julia Kowalska, Unseen, an animal, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.