Prioritizing preservation: reclaiming cultural significance in the modern age

We currently live in an era where preservation often takes a backseat. Whether it’s deleting social media content after a season or neglecting human relationships and valuable spaces, we often fail to recognize the cultural significance behind our actions. It’s crucial to shift our mindset and prioritize gestures, people, and the environment around us.

bplus.xyz (b+), a collaborative architecture studio operating at the nexus of theory and practice, utilizes various mediums and approaches to tackle contemporary challenges, especially those concerning socio-ecological transformation and the adaptive reuse of existing buildings. With environmentally and economically sustainable solutions, b+ embraces the potential of our existing built environment and aims to unlock its latent possibilities. Through a collaborative model, b+ emphasizes working with diverse actors and stakeholders in project development.

To start our discussion, how does bplus.xyz (b+) practice address contemporary challenges like social-ecological transformation and adaptive building reuse with economically and ecologically sustainable solutions?

Jonas Janke: We as b+ understand architecture as an open process, and view buildings as part of larger systems that require a systemic approach. We see the given framework of existing buildings and legislation as an active design tool that carries the potential for transformation within. Thus, we celebrate the potential of the existing built environment, and aim to reveal and activate the latent potentials that lie within.

To do so we are working with different formats – films, political activism, campaigns, exhibitions, symposiums and of course our projects should serve as build arguments that represent an alternative approach and perspective towards the mentioned contemporary challenges.

Jolene Lee: Continuing on what JJ said, b+ engages in formats and fields “outside” of architecture or what is expected of architecture, especially legislation and politics because we understand how the decisions made on that level affect our built environment socially and ecologically. We strongly believe that to change the system is to work in the system.

Therefore, our design projects are not unique design approaches to the reuse of existing buildings or structures, instead, they stand as built arguments, prototypes, models, and answers to our contemporary challenges (finiteness of resources).

I’d like to focus on the renovation of the Ernst Lück lingerie factory. How does the renovation of this factory in the former GDR extend beyond surface improvements, and what wider implications does this approach hold for architectural practice?

JJ: The Antivilla is a project where we were client, investor, developer, and architect all in one. The intention was to develop a case study that defines a new way of energy-efficient refurbishment.

The name “Antivilla” doesn’t protest against the concept and typologie of a villa, but critiques the resource-intensive lifestyle of villa dwellers. It raises the fundamental question about how comfort can be defined and redefined in the future.

For this reason, the energy demand calculation was applied differently than usual and off-standard solutions were also implemented – for which any other client would very likely have sued us, or at least wouldn’t be comfortable to accept this nonconformity. But we were confident and also couldn’t sue ourselves, so everything was possible.

The abandoned 500 square meter building was not appealing for future investors due to the high demolition costs. In addition, a regulation states that any demolished building could only be rebuilt with 100 square meters of living space, 20 percent of the existing volume. Demolition therefore would have caused a massive loss of gray energy in terms of both labor and material. The concept thus contains a number of selective measures that permit its new usage as a studio and a residential building and of course the aforementioned question how comfort can be defined or redefined in times of resource scarcity and climate-crisis.

Furthermore a financing trick was applied: When buying the property from the former owner it was said: market price minus demolition costs will be the purchase price (what we pay), since the application for the new 100 square meter house was on the table. Towards the bank/credit institutions it was said: “Well, building-shell already stands, this is our own contribution, the transformation will be financed.” Interesting is that we gained value from something which is considered to have no value – a house which shall be demolished. Nice plot twist – right?

One widespread definition of architecture is: Architecture is everything that makes us humans independent of nature. Reyner Banham (architectural theorist) understands that we need to protect ourselves from certain extremes of the environment, but that the environment should be seen as a dialogue partner to architecture – as an integral rather than an external force.

The approach of Antivilla is rethinking Reyner Banham’s concept in The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (1969) and combines his two distinct principles of space creation: Constructive- and Energy-supported Space Generation.

Constructive vs. energy-supported space generation:

This can be explained quite simply with a short story, like Reyner Banham used to describe it:

People, imagine for example scouts, are given wood to set up camp in the forest.

One part of the group builds a roof and protecting walls with the wood > constructive space generation.

The other part of the group takes the wood and creates a fire to warm themselves > energy-supported space generation.

The existing exterior walls are kept like they are – not insulated – comparable to the approach where the people used the wood to build a roof and walls > constructive space building.

The core acts like the central fireplace in a classical farmhouse.

This is comparable to the fire > energy-based space formation.

Around that core are translucent curtains installed. The curtains are a key element of the project – they allow different temperature zones to be set up without having to use permanent room partitions. In Winter, the heated room shrinks to an area around the core of about 50 square meters; in the Summer, it can expand and increase the usable area to up to 250 square meters.

In this way, the curtains are allowing flexible climatic conditions. A temperature difference of 12-13 degrees is created because the curtains are not really insulating but they are stopping the circulation and loss of warm air.

The functional principle of the Antivilla could be described as the adaptation of “The Well-Tempered” to the “Differentiated Environment” through its adaptable climate zones but can also be described as: “New Primitivism” since it is actually following well-established traditional low-tech approaches.

The project gained widespread attention due to its visually striking architecture and its controversial but comprehensible approach. It was able to leave the architectural bubble, by being featured in publications like the New York Times Magazine. Only such projects have the potential to influence collective societal perspectives and raise a new awareness.

In the opening scenes of the film “Themroc”, Faraldo presents a society where strange creatures struggle to communicate amidst a cacophony of urban sounds—cars, horns, subways, doors, engines, coughs, and the bustling footsteps of commuters. How does Faraldo’s experimental film “Themroc” (1973) relate to the renovation project’s significance?

JJ: The creation of the holes in the facade was celebrated as a collective happening. Friends and collaborators were invited, food and beer was offered and sledgehammers were prepared to be used. As an Ad-Hock-Action, holes were punched in the face where needed – towards the lake and towards the forest. Logically, in a former production building, the focus was not on the view, so these window openings were missing.

Due to the new concrete roof which replaced the contaminated asbestos roof, a structural principle was created which allowed the freedom to punch holes in the facade wherever you want – the only requirement was to keep the corners of the existing perimeter walls. It was a celebration of the new acquired freedom to spontaneously shape views. Here again the processual thinking in a project can be recognised, which was mentioned in your initial question.

But at the same time it raises again a question of standards and definitions – is an archaic hole in the facade also a window?

So the spontaneous, archaic and rough celebration of this action can be also found in the movie Themroc, when he decides to live isolated like a caveman in his apartment and also punched a hole in the facade as an act of protest and liberation.

Now I would like to talk about a project that in a way brings me back to my country. What inspired the idea of “San Gimignano Lichtenberg,” and how did it contribute to reshaping the narrative of the area?

JJ: For all those who don’t know the original “San Gimignano”. San Gimignano is a famous Italian village in Tuscany, which is known for its towers. Every year thousands of tourists travel to San Gimignano to visit the small historic village, which is situated on a hill, and experience “la dolce vita”.

Now to our project “San Gimignano Lichtenberg” and why we had to borrow the image and history of the Tuscan mountain village with the towers.

The two towers – one the former staircase tower, the other the former coal and graphite silo – are remnants of the state-owned company “VEB Elektrokohle” from the GDR era. After the fall of the Wall, the once divided Germany became one again. Many facilities and equipment were now duplicated, including the semiconductor factory in Lichtenberg. Its use became obsolete. Due to the high demolition costs of the two concrete towers, the properties were not very attractive to investors. The ruins remained unused and empty until 2010.

Back then, one went to the bank with the idea of transforming the former silo tower into a prototype workshop and reported that these unbreakable concrete ruins in Lichtenberg were the starting point.

This did not meet with much favor and funding was refused.

But the invention of the story about the town of San Gimignano Lichtenberg brought the long-awaited success in a second attempt to acquire funding. The vision of San Gimignano Lichtenberg with its powerful words and images captured the imagination of the bankers and they began to believe in the place and the project. Financing was secured.

The realization that a strong narrative, as the first non-architectural intervention in the project, was necessary and decided whether the project would fail or not, clearly showed us as an office that storytelling is a crucial tool for us architects.

This led, amongst other things, to the reason why today the chair at the ETH in Zurich of Arno Brandlhuber “station+” does not teach how to draw floor plans, but how to do storytelling effectively and convincingly – because this is a skill that is not usually taught as part of an architecture degree.

How was the meaning of the two towers enhanced in order to shift away from the perception of them as mere ruins?

JJ: The towers, as they stand there today, embody more than a mere ruinous existence. Externally, they may have not changed significantly. Programmatically, however, they have.

From the rooftop today, one ponders the future of architecture as a response to evolving needs and values, symbolised by the towers amid shifting political, economic, and ecological landscapes. Recent crises underscore the rapidity of change in local and global affairs. The imperative for fundamental change challenges the notion of no alternatives. Cultural values are embedded in the frameworks of daily life. Amidst zoning complexities and development pressures, the question arises: how will we live together? Architects must confront issues of speculation, segregation, resource use, and technology escalation, seeking strategies for a shared and improved future through adaptive reuse of existing structures.

The b+ prototype workshop is seen as a built argument and cultural capital.

On the one hand, it is intended to highlight the potential of existing buildings and draw attention to the seemingly “useless”. The existing stock is a valuable resource – this we all need to understand.

On the other hand, the site offers affordable workspaces for young up-and-coming practices and serves as a location for events and symposiums.

Keller Easterling emphasises the importance of architects considering the broader cultural impact of their designs beyond their physical form. In what manner does architecture become an argument for the ongoing change in society? And, in your opinion, why is it crucial for architects to consider the broader cultural impact of their designs beyond their physical form?

Roberta Jurcic: We as architects have a complicit role in what is happening in the world around us, and often it feels like we have no agency and are forced to act based on the economical pressure. Therefore, our office’s main challenge, as architect and transformation scientist Saskia Hebert puts it, is to establish a self-sustainable practice in times of post-growth, where we engage with the projects that align with our agenda. Once you acknowledge your responsibilities, you understand that everything you do has a broader cultural impact – from window detail, to who is your client, to what competitions you partake in, and how you challenge the status quo. JL already mentioned, changing a sentence in the law often has bigger impacts on the built environment than a design for a freestanding family house.

Speaking of social and cultural impact, I cannot fail to mention the Mäusebunker. How does the history of this building mirror broader societal perspectives on human engagement with nature?

RJ: Storytelling, symbolism, cultures, and society have a long, intertwined history. Is there a better story than converting a bunker-like former animal testing laboratory into a showcase for cohabitation between humans and non-humans?

What challenges does the Mäusebunker face in finding a new purpose, particularly in light of contemporary legislation such as the Climate Change Act, and how does the preservation and conversion of buildings like the Mäusebunker contribute to promoting climate neutrality by 2045?

RJ: The biggest challenge lies in finding a way to fit buildings that formerly had a different use into the building requirements of the new program. From the “unexpectedness” of the existing building to fulfilling basics like ceiling height, light, and air/ventilation requirements. This challenge can also be seen within the current topic of transforming office buildings into housing. The biggest contribution in terms of climate presents understanding that if we take these acts seriously, firstly, we don’t have enough “CO2-budget” to demolish buildings.

Secondly, understanding that those buildings are massive storages of CO2, and their demolition can be compared to cutting down parts of forests. Finally, understanding that no matter how passive a newly built house can be, it can never compete when we count the invested energy into the existing building, the energy for its demolition, the energy for a new building, and then in the end comes the “maintenance” energy difference that is insignificant.

How does Germany’s commitment to reducing CO2 emissions align with the assessment of the existing building stock’s value, particularly in terms of invested energy?

JL: If we understand today the real price of CO2 emissions in terms of not only economical but also social and ecological values, then we know that our building and construction sector cannot continue business as usual – we need a radical change. Especially after the 2019 pandemic, we have seen what today’s world is capable of (pausing rapid consumption).

We need to see our existing building stock as “storages of CO2” (Oana Bogdan, The Demolition Drama). Instead of the tabula rasa approach, we should regard our current urban fabric as the status quo, work with the existing, and take the challenge to “build on the built” (Herzog & de Meuron, The Demolition Drama). This is one of the ways we can contribute to the commitment of reducing CO2 emissions at a much lesser cost (if we assign values to material based on its finiteness and the catastrophic consequences of its depletion).

JJ: Indeed and we should also see this as an opportunity for us as architects. You often hear fellow architects complaining that the enormous pressure from project developers, who have to keep within budget and cut costs, which in turn can only be done by saving on materials or labor, leads to the same architecture over and over again.

You don’t want to design buildings for which plans just have to be pulled out of a drawer and applied to plots like stamps.

That’s why I said that we have to see it as an opportunity to be creative with the existing and work within the context of the existing. The existing always holds new tasks and challenges in store – isn’t that great?

HouseEurope! Tell me more.

Based on everything discussed, it is within the DNA of b+ to engage with the task of dealing with the existing, with something old, considered waste or valueless by coming up with creative solutions, both legislative and economic. This spirit has resulted not only in built projects, but as well in films and initiatives, namely, Legislating Architecture, The Property Drama, and Architecting after Politics as well as RGB 165/96/36 CMYK 14/40/80/20, and Global Moratorium on New Construction.

HouseEurope!, our latest initiative, is a non-profit organization which advocates for the preservation of the existing building stock against demolition by speculation. In the long run, building on the legacy of the investigations undertaken by b+ (formerly known as Brandlhuber+), HouseEurope! aims to be a policy lab in which the research on legislating architecture can manifest in different forms such as the upcoming European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) campaign.

ECI is a tool for direct democracy founded by the European Commission themselves since 2011. Inspired by Swiss referendums that allow a popular vote on new laws, the ECI enables EU citizens to propose new laws or suggest changes to existing ones. 1 million EU citizens from at least seven member states can invite the European Commission to consider their proposal and dedicate a working group to assess their submitted claim. This provides citizens a direct say in the EU policy-making process and a platform to raise awareness on important issues.

HouseEurope! is a growing team of citizens that brings together diverse perspectives and expertise from the fields of architecture, labor, and politics. Backed by industry leaders and educators such as Lacaton & Vassal, Herzog & de Meuron and Architectural Council Europe (ACE), we are committed to creating precedents for the social-ecological transformation of how we live together.

Subscribe to our newsletter or take an active role here.

How does the HouseEurope! initiative aims to address the issue of building demolition driven by speculation?

Theoretically, we understand that this issue can be made aware through a trifecta of social, ecological and economic factors. If we take seriously the aim of the EU to be climate neutral by 2050, we have a lot of work to do. Looking at our building and construction sector, we are contributing 35-40% to CO2 emissions. On the other hand, the finiteness of building land and material leads to rising construction costs where the same building costs more and more. Yet, we are still building, but more of the same generic buildings that we can still afford, which is a result of reducing material and labor as mentioned by JJ previously. With these two arguments in mind, we are also facing a housing crisis where we are running out of buildings to house people. How can that be? Some food for thought.

Concretely, we identified several legal levers to incentivize the keeping of existing buildings which can be submitted through the tool of ECI that can tip the scales for the greater good. We are currently drafting the legal proposals with EU lawyers and advisors to be submitted this year. Alongside, we are also collecting successful renovation stories to showcase best practice cases of social-ecological transformation of the existing building stock through measures focused on building preservation, adaptation, renovation, and transformation.

How can we effectively promote the socio-ecological transformation of existing building stock, particularly among younger generations who will play a crucial role in deciding where and how to purchase homes in the future?

JL: To answer the first part of the question, I believe that transformation starts with education and public awareness. We are already seeing movements from the younger generation such as Fridays for Future, demanding issues to be tackled within this generation and not postponing it to the next (and the next). Perhaps the harm on the planet caused by the vicious cycle of demolition and rebuilding driven by speculation is niche knowledge today but it will very soon be common sense like deforestation and ocean pollution. As a practice, we take part in this mission to raise awareness through our previously mentioned initiative, HouseEurope!.

As to the latter part of the question or more like statement, I personally am conflicted at the thought of promoting where and how to purchase homes in the future because maybe homes should not be a commodity to be bought and traded, instead, evolve into a common way of designing spaces for and by the society by challenging the current model of asset ownership.

JJ: We have all understood (at least I hope we have) that we should stop using plastic bags and reduce traveling by plane to a necessary minimum in order to reach or come close to the climate goals we are aiming for. All these campaigns to raise awareness are being passionately supported by and thanks to the younger generations.

I think we have to continue exactly as they are showing us. Make built arguments (realized projects) accessible as positive examples. We give free guided tours of our projects almost every week for students, other architects and generally interested people. In this way you become familiar with our way of thinking and approaches and knowledge and information leave the architectural bubble.

However, easily accessible media such as film and exhibition contributions should also be pursued further.

HouseEurope! is really exciting and has a dimension of political activism that we have never done on such a large scale before. But we are motivated, confident and optimistic that we will succeed. Imagine that, as architects, we can directly influence the legislation that affects our own actions.

Where and how to purchase homes in the future. Good question! Especially in times when the chance that we will one day be able to call a house our own is getting smaller and smaller. The question of alternative ownership models is justified. Or whether we should pool our strengths and financial resources and work together with several parties and people who have the same interests.

“Renovate, don’t speculate” serves as a powerful life philosophy. In an era where preservation often takes a back seat, it’s crucial to activate existing spaces, adapting and renewing them to meet our needs. Achieving socio-ecological transformation requires empathizing with the space and the stories it carries. Personally, I’ve embraced this motto by purchasing a small space in a refurbished 1800s cotton factory, which I now proudly call home. Living here allows me to connect with local history, reflecting daily on the actions of those who worked here two centuries ago.

Credits

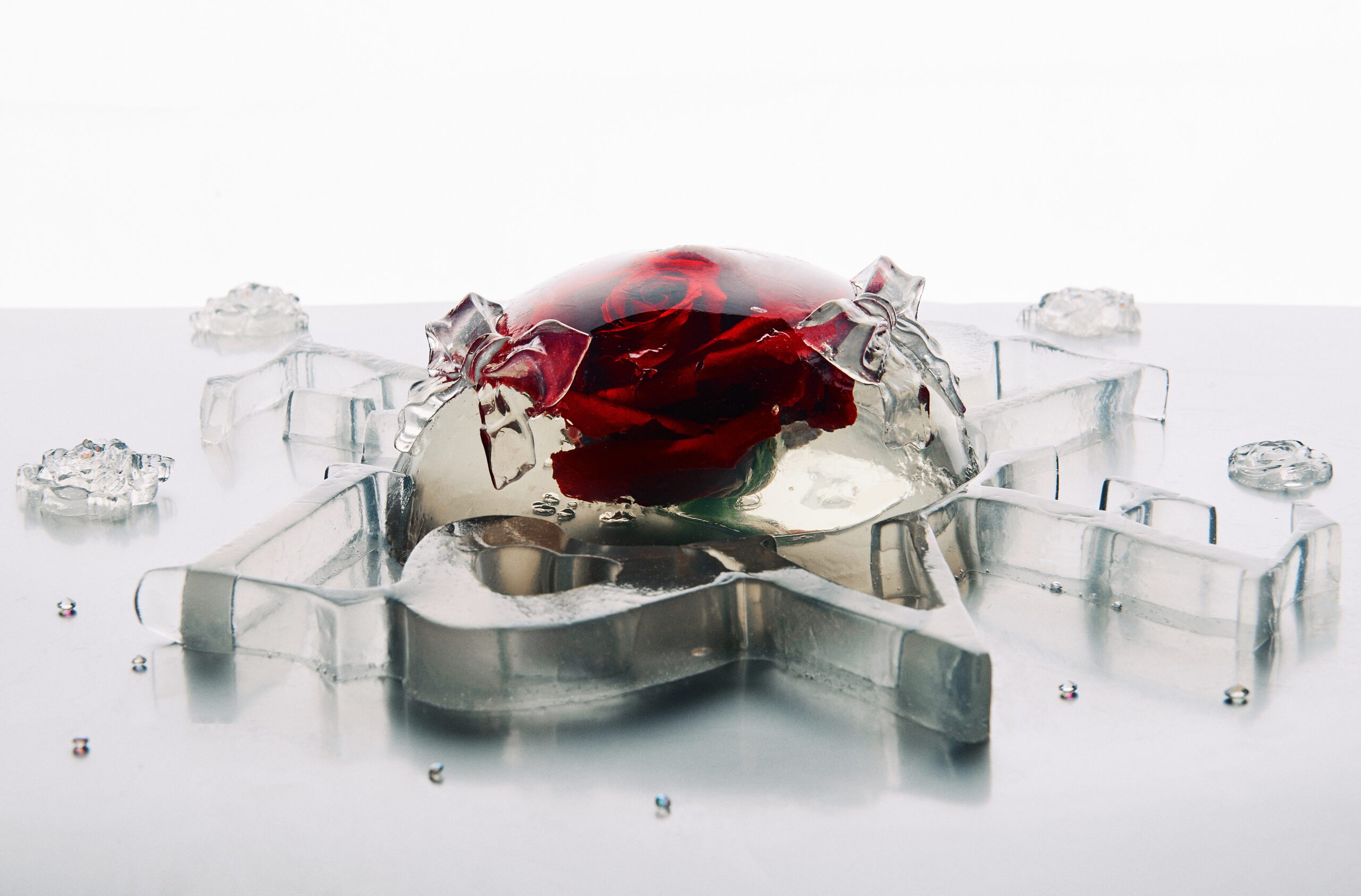

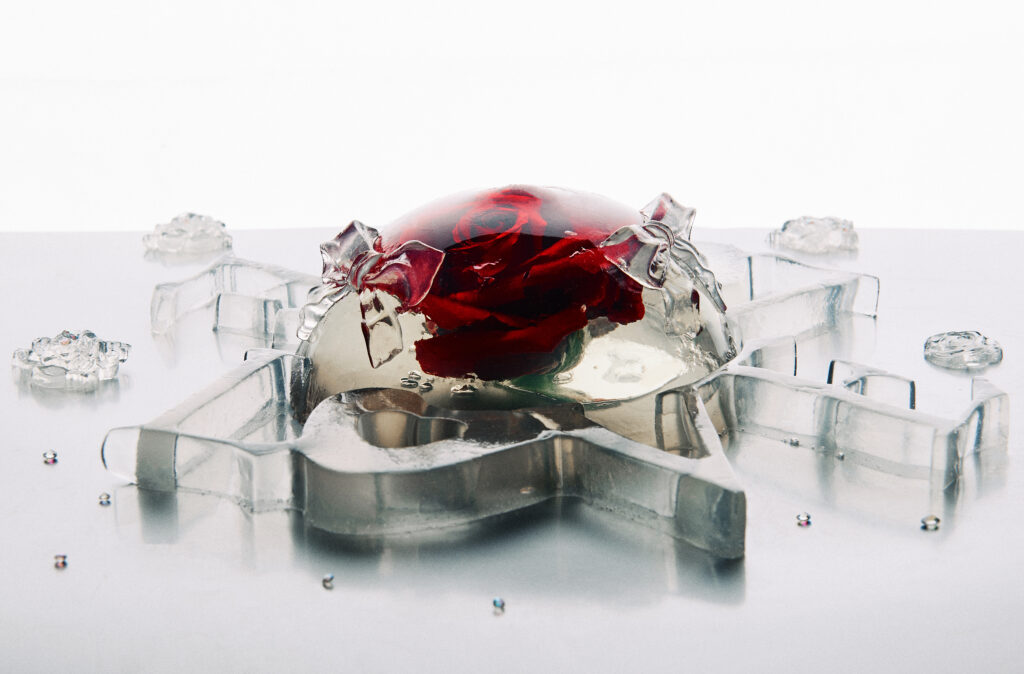

- Antivilla, 2010-2014. Berlin. Photography by Erica Overmeer. Courtesy of Erica Overmeer.

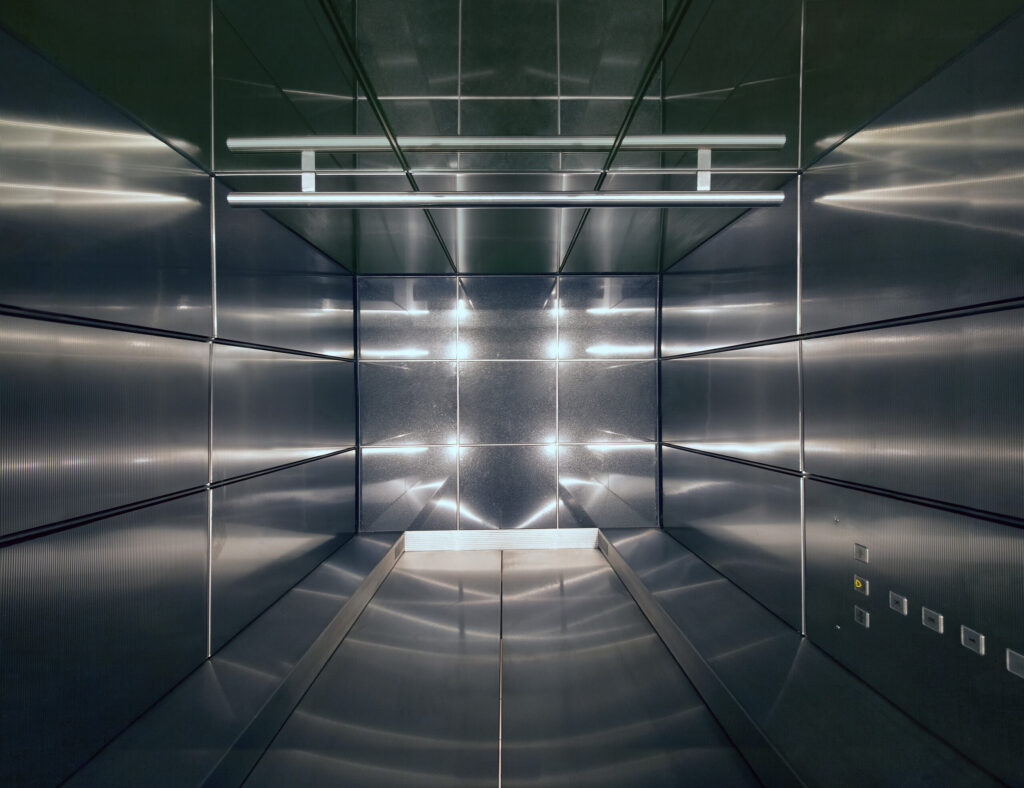

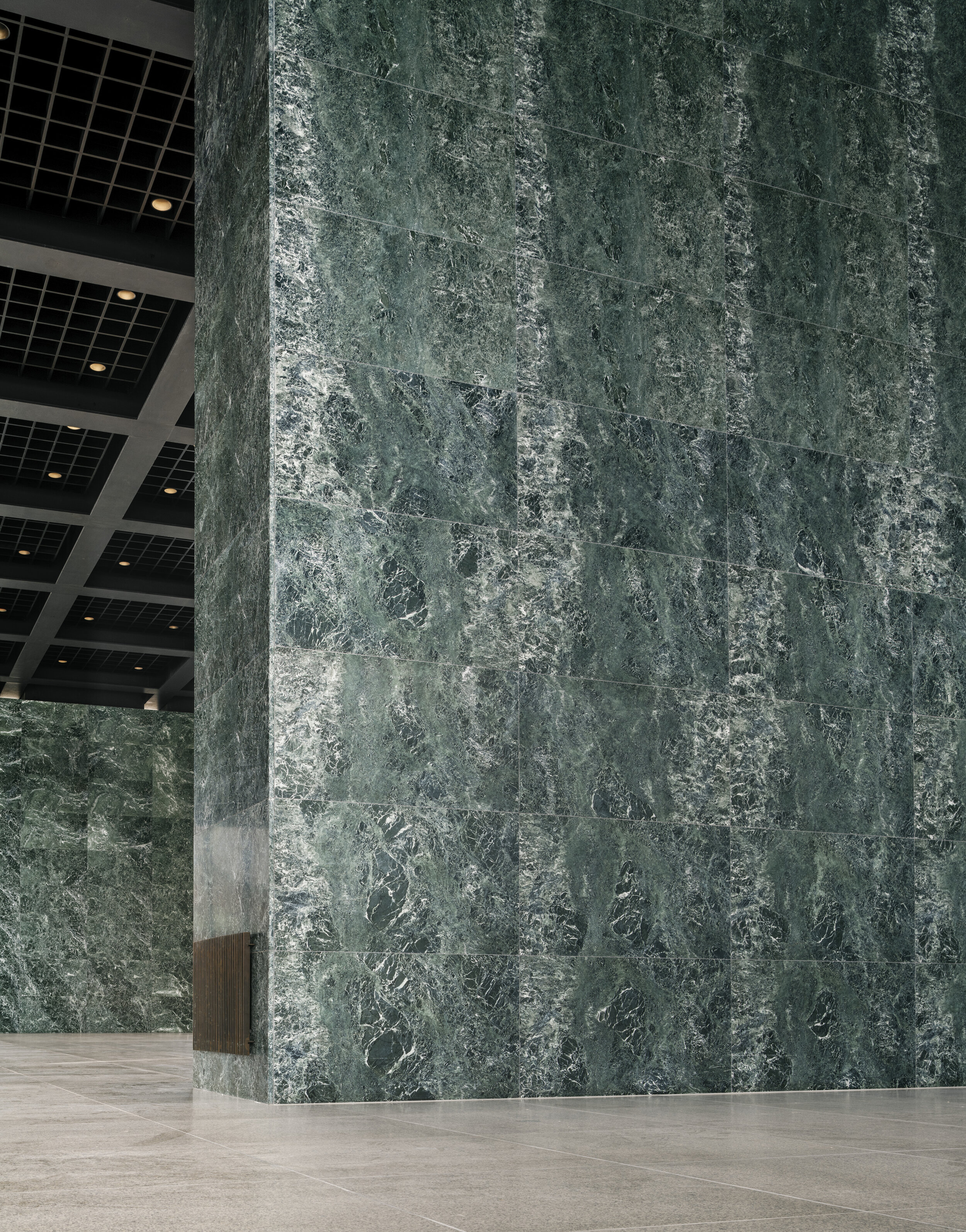

- San Gimignano Lichtenberg, 2012- . Photography by Erica Overmeer. Courtesy of Erica Overmeer.

- Mäusebunker, 2022- . Berlin. b+. Film stills. Courtesy of b+.

- HouseEurope! Film stills. Courtesy of House of Europe.