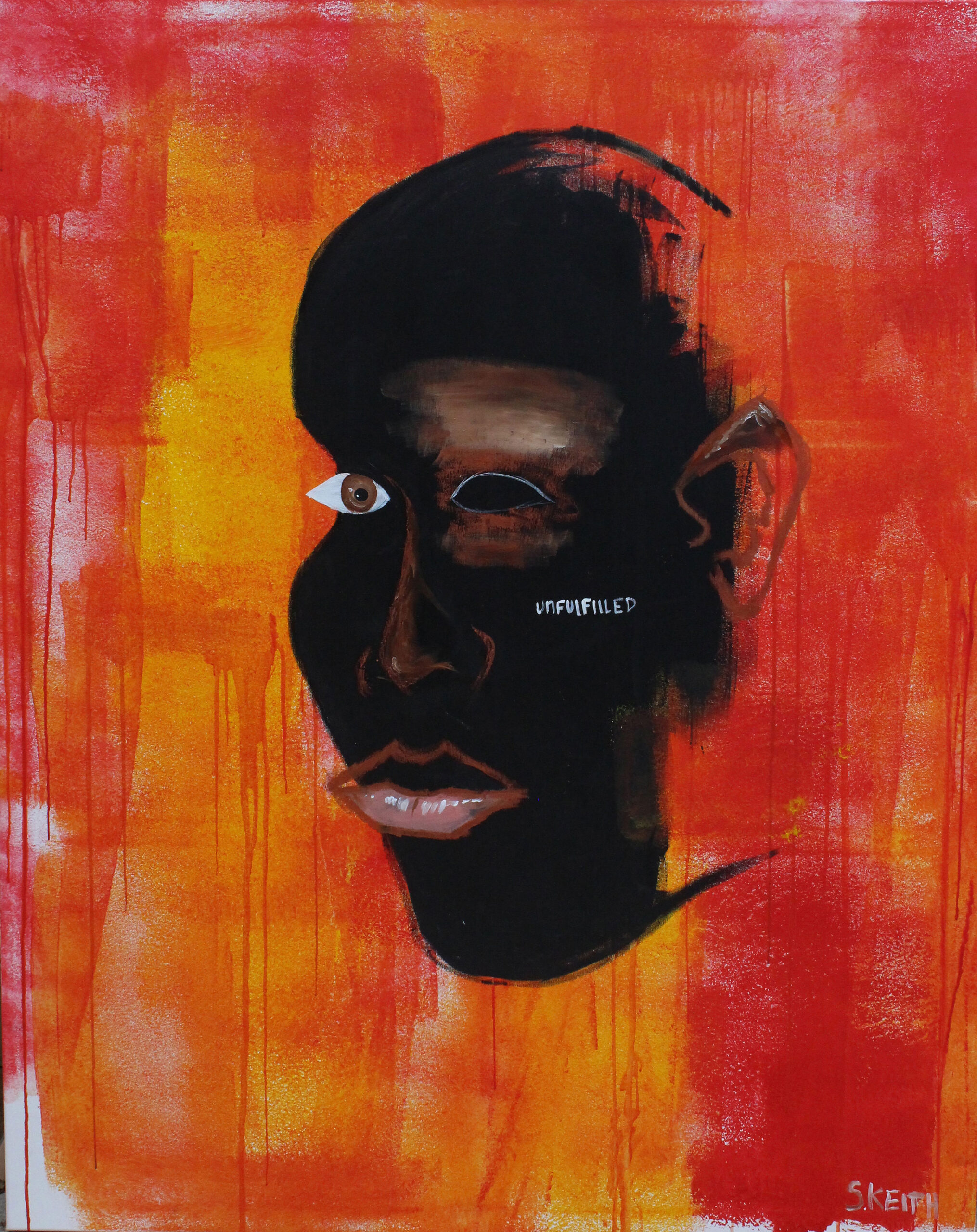

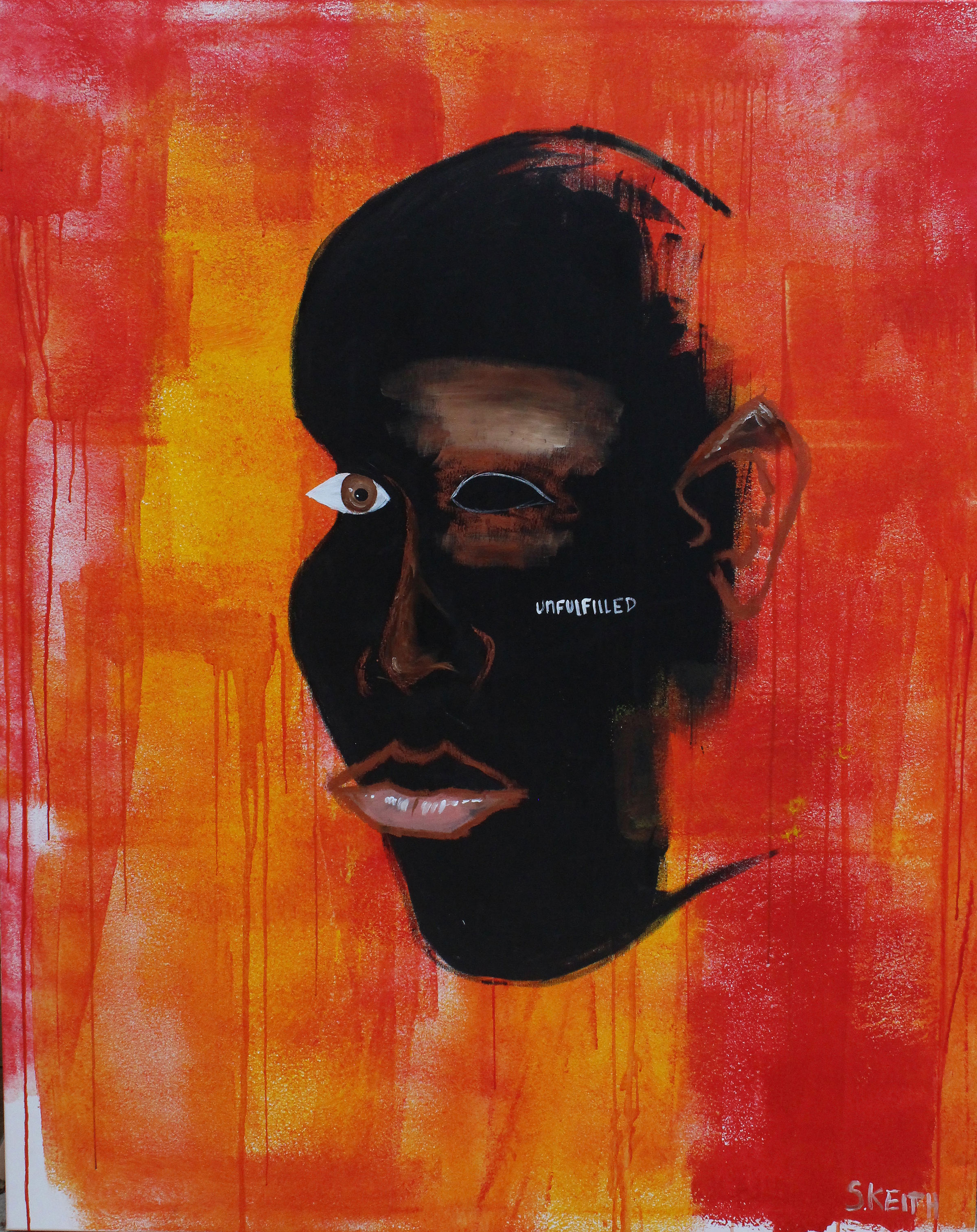

“alienated while completely connected at the same time”

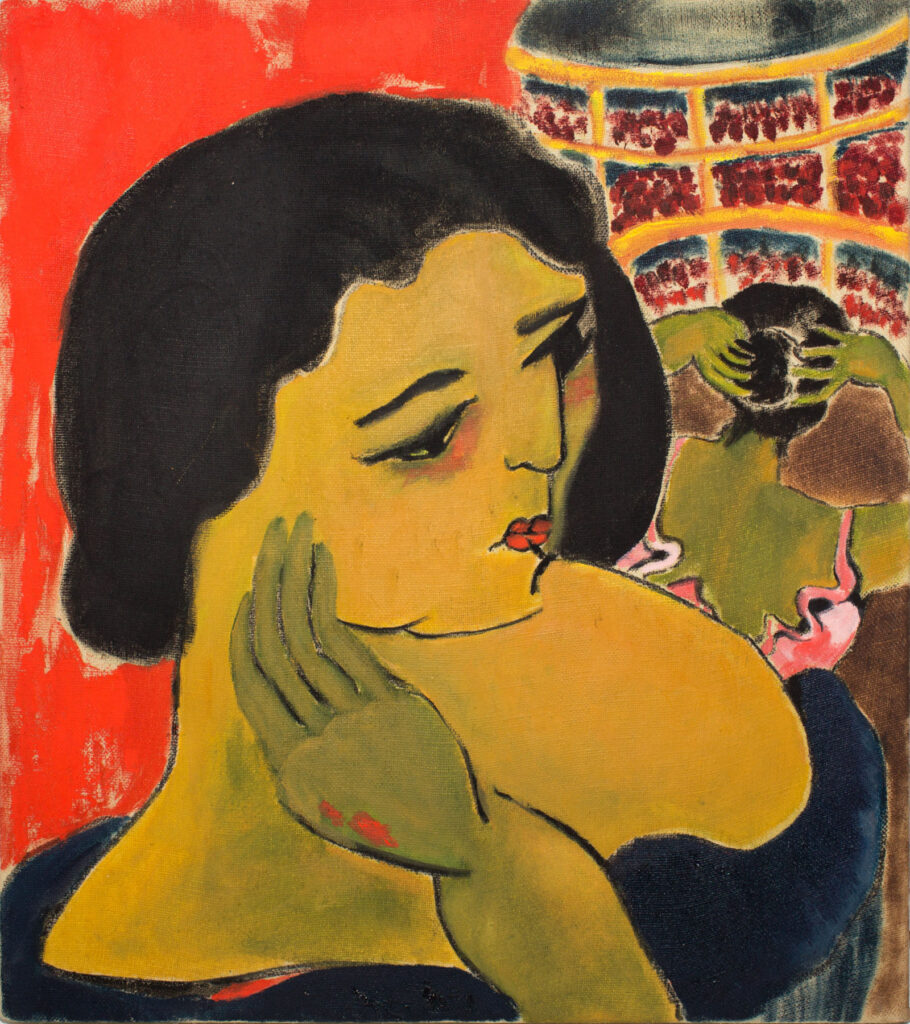

Their work move between different languages such as sculpture, installation, kinetic art and painting. The modus operandi: to constitute itself as a subject, and from its mechanic materiality, to point to transcendence, to mysticism and to the unknown. Encompassing installation, drawing, painting, sculpture, performance, sound and video, Lolo & Sosaku’s wide-ranging practice explores the capacity of creating new meanings through the association of the objects, the surroundings and the spectator. Taking inspirations from ancient Greek sculptures, from Dada and Bauhaus School to Jean Tinguely, Alexander Calder and Jean Dubuffet, Lolo & Sosaku soon altered the traditional artistic practice concentrating on the possibilities inherent in the materials they used often metal, wood, glass, incorporating music and sound. Electronic music is certainly the highlight of their inspiration as a complex language translated into sound installations and sculpture compositions. Shapes, lines, materials and sounds are assembled together into motion sculptures that perform taking their own voice in an unpredictable continuous transformation Exploring many artistic horizons and redefining boundaries, their interest is the energy and the hidden forces that guide life in our technological age.

Lolo, Sosaku! You guys. Truly beautiful to meet you last week. So, lots of things were said and I thought of some recap key ideas that stayed floating around. I would start with SONAR, in which you just performed a few days ago.

Given the present pandemic context, you have just been part of the (first ever) virtual edition of SONAR, where you live streamed from your studio in L’Hospitalet.

How did this situation feel? How did you conceive producing this piece to fit an iPhone screen? (Modern times…)

Lolo: We felt in a way alienated while completely connected at the same time. Is the digital streaming behind this or is it a more global thing related to the current situation? Maybe both, yet we are anxious to be back to physical exhibition dynamics.

Sosaku: Visualizing our work through phone screens was conceived as an amplified version of our usual visualization mediums or supports, always having in mind that the spectator completes the artwork, even from the other side of the screen.

L: Our piece Concert for four pianos is an audio piece interpreted by non thinking machines installed in four pianos, they are sound sculptures that generate different textures and audible rithms. With this sounds we composed a sound piece with Sergio Caballero and thats the piece we presented in Sonar, putting up three shows for a reduced audience from our studio and a concert that was showcased for the whole world from Sonar’s live plataform, it was a great experience.

We understand our artwork as something that happens between a gap in what we conceive as the “present”, where concepts of space and time are no longer a unified continuum and act as separated entities.

S: We feel comfortable working in this temporal space.

L: With the years, we have created our own reality, as Arca coined it the last time he was in the studio. “A world within a world”.

Do you have hopes that our future may shift back into a less technological reality, in a sort of resistance act, or do you encourage the exploration of technology in this sense?

L: We are living in really particular times, exposed to constant sudden changes, in an accelerated way. The Anthropocene, the current geological time according to Paul Crutzen, is characterized by the visible and signicative influence of human behaviour in the planet… for some theorics it goes back to the industrial revolution… inexorably this age would evolve into the Post- Anthropocene, which, in conversations with Maike Moncayo, we differ in how it will take place, given that for her it will be the communion of human-machine-nature, forging a new ecosystem of renewable energies and a way back to the natural equilibrium of the holocene. Our vision is a bit darker given that we believe that we will evolve to a kind of machine – human symbiotic being, to survive climatic changes and death, where nature will be in a second plane or extinguish, given that it wont be necessary.

When we met, we talked about your artwork’s translation from the physical, tangible world into the two dimensional language of video or photography.

You mentioned a particular experience with Disco, where the audience thought you were presenting a 3D render, when actually there was an actual disc and a whole physical effort behind it.

Did this experience transform how you conceive future artworks?

S: To forge Disco, a huge human physical effort was necessary. Lots of months of hard work interpolated with unplanned difficulties. It was a great adventure, and I was working sick for the whole of the production.

L: Disco is a site specific project that works in dialogue with MentalStones, a permanent installation by Tito Diaz, which is situated in an olive field in the Delta del Ebro area, far away from civilisation. To our surprise, when we published the first images of the project, we received several reactions which interpreted that the artwork was a 3D render. We had put so much into it that the final piece looked artificial, like a render…

Even though Disco exists in the intersection between sculpture, land art and video art, we had never imagined that the audience would interpret it as a digital artwork.

S: We think imagination is sometimes digital.

L: It is a constant transformation… the digital looks for the organic, the real mutates into a digital language. We are exposed and immersed in a constant digitalization of everything, I wonder if Disc would have actually been a digital render, would it be real?

As sensible subjects, what interests would you say you pursue or dig on through your practice?

L: We see autonomous intentions in the behaviour of some of the machines we create, which escapes any logic understanding, as if they acquired a soul-condition, or something like it.

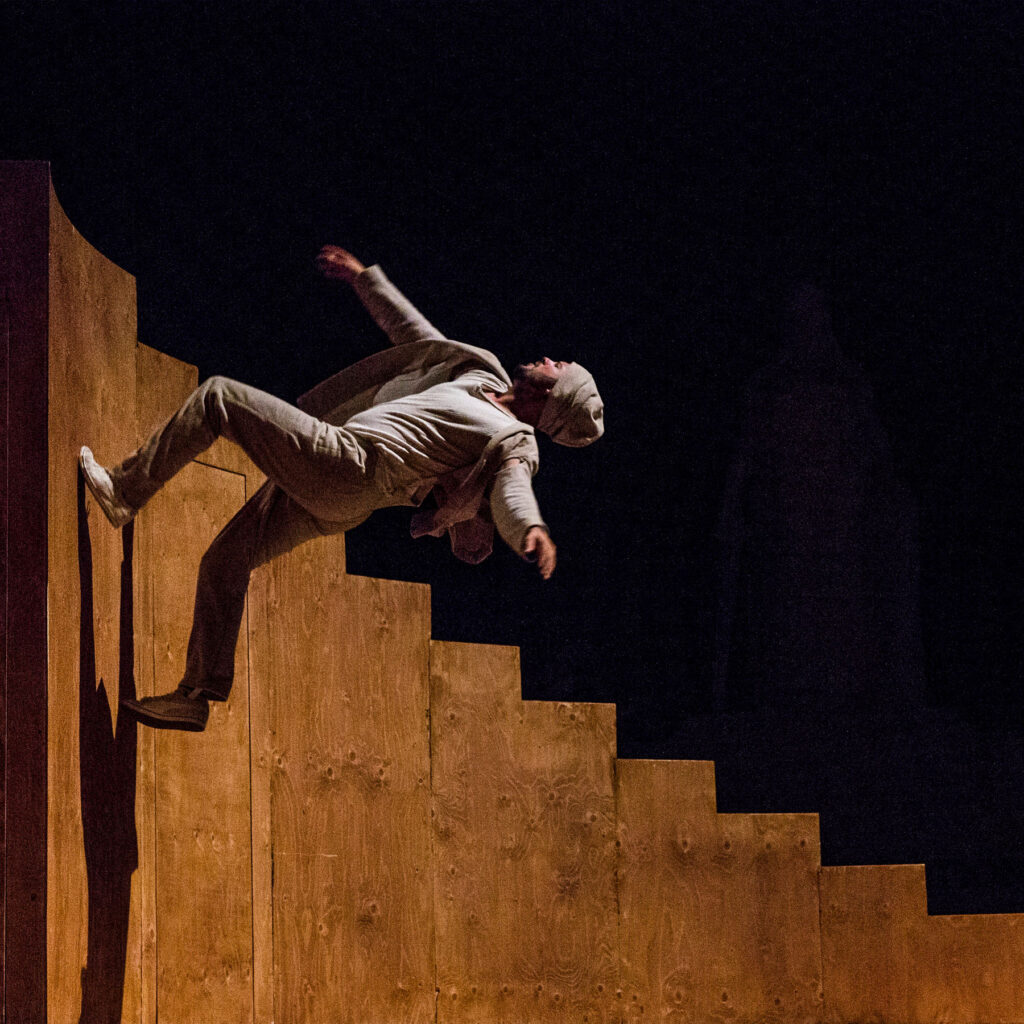

S: When we did the theater piece we had various press conferences… conventionally, actors also assist to this conferences so we took with us Tipo P, one of our sculptures, which was the protagonist of our piece. I was with him for many days, travelling by metro and taxi to different places, and a really close nexus evolved.

L: Tipo P did really bad in the first interviews.. as if he were nervous. He changed attitude once he was in front of cameras… thank god he did really good in the actual performances.

S: Yes, he’s a really good actor.

Being that you come from so far apart (literally, Japan-Argentina) the fact that you have found each other and created this artistic communion, to say, feels like a magical encounter, your artwork, this synergic creative act, like an alchemic process. Do you believe in chance?

Have you ever thought about how your paths could have shifted if you had not ran into each other?

S: We’re really close friends and we sort of like the same stuff.

L: The first time we met (early 2004) we could barely communicate because we practically didn’t speak english… and naturally we started creating stuff and working together… we developed our own language and work methodology which imprints itself in all of our work.

S: Now we work in the same ways as in the begining, but in bigger projects.

Lolo: Nowadays when I think of that first encounter, in like how this unexpected chain of events brought us together, I feel very grateful.

S: Yes, if I think about that I feel as if an exterior force had joined us in some way.

L: Maybe that is chance, two independent processes that converge… Lucrecia, you were asking if we believed in chance, we do believe and we implement it in lots of our artworks, maybe the most evident one would be Panting Machines.

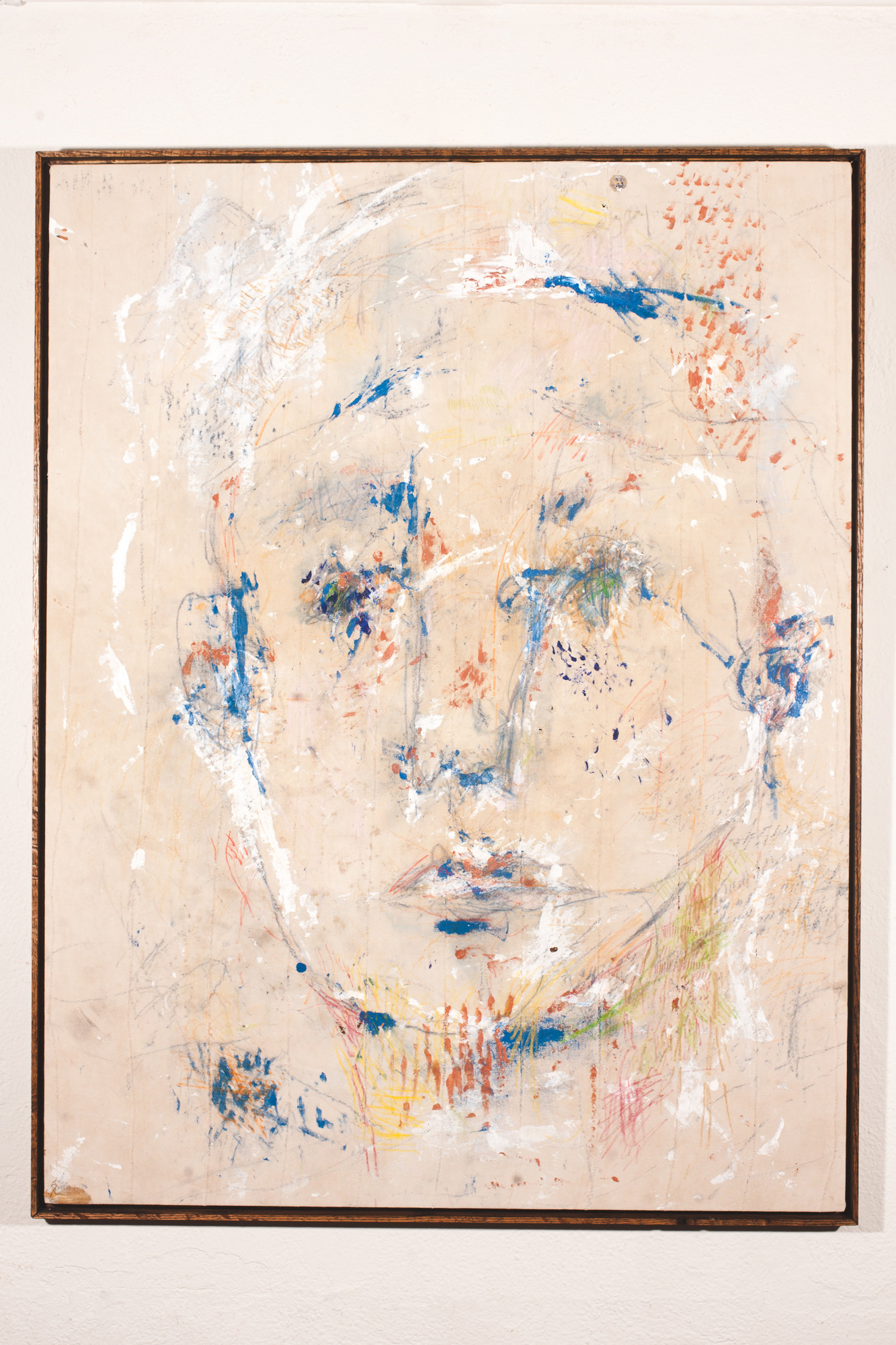

S: We build machines that have as an objective to paint or draw, and though we are very present during the process, they paint what they autonomously desire to paint, and when there are more than one of them, lots of times they collide, change paths and generate new lines and shapes, mixing their traces.

L: There’s a whole narrative revealed in chance.

This issue of NR has the concept of Change as its main trigger. It is obviously a word that resounds in all of us given the pandemic context, in any of its multiple consequences. If you would be able to propose, within a utopian scenario, activities or rules for a different society… what would you suggest, if anything? All valid. And… calling on utopia, would you recommend any readings, movies, or tracks that have triggered your imagination, your conception of life or reality?

S: Create a new civilization, without violence, where everyone has access to everything.

L: In the conversation we had before this interview, we really liked something you asked regarding the spaces we use to install our artworks, which are generally abandoned spaces or spaces in which our artworks establish dialogue or modify them, you were asking if we had thought of building an entirely new space that would not only host our pieces but be an intentional enviroment for them. We could do the excercise of replying to this question with the creation of a utopic social space, a place where there are no physical limits, where anything you can imagine is possible.

I’d recommend the amazing documentary “L ́homme a mangé la terre”, by Jean- Robert Viallet

S: Yes, I’d say also the last book by Yuichi Yokoyama “New engineering”.

Credits

www.vimeo.com/loloandsosaku

www.instagram.com/loloysosaku

www.loloysosaku.com

Lolo and Sosaku’s work has been exhibited and performed, amongst others, at

Museo Reina Sofia (Madrid, Spain), MACBA Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (Barcelona, Spain), PSA Museum Power Station of Art (Shanghai, China), MIS Museu da Imagem e do Som (São Paulo, Brasil), Fundation Gaspar (Barcelona, Spain), Fundação Casa França Brasil (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil), Sónar (Barcelona, Spain), Matadero (Madrid, Spain), Palace of Culture (Iasi, Romania), MAVA Museo de Arte en Vidrio de Alcorcón (Alcorcón, Spain), O Art Center (Shanghai, China), Luis Adelantado Gallery (Valencia, Spain) and Instituto Cervantes (Milan, Italy).

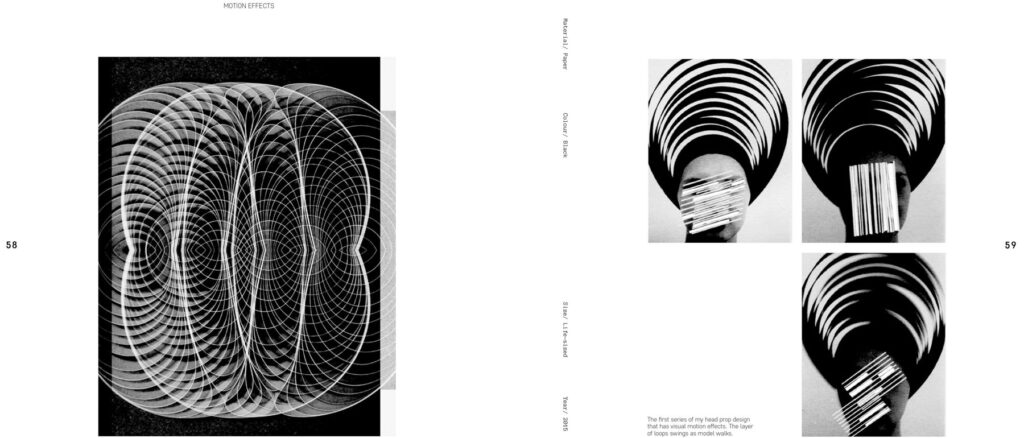

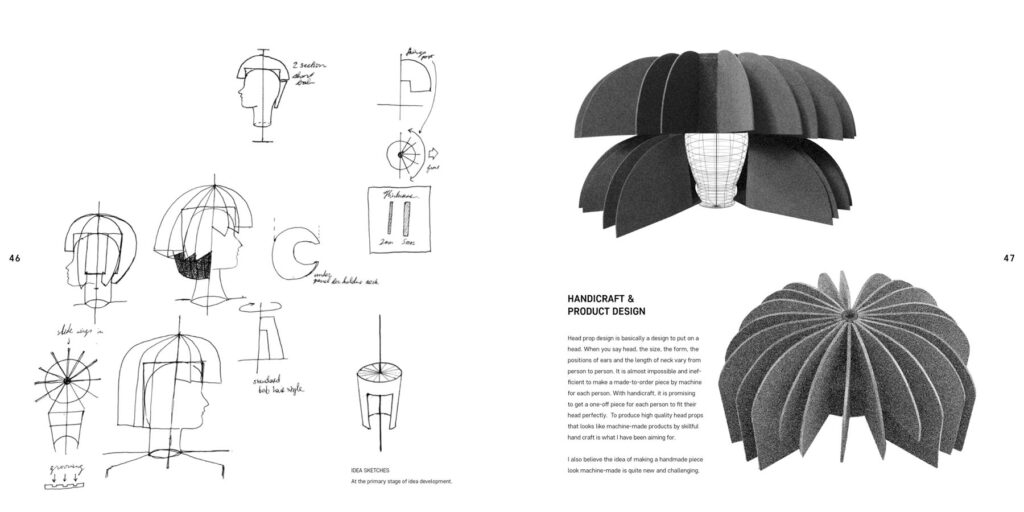

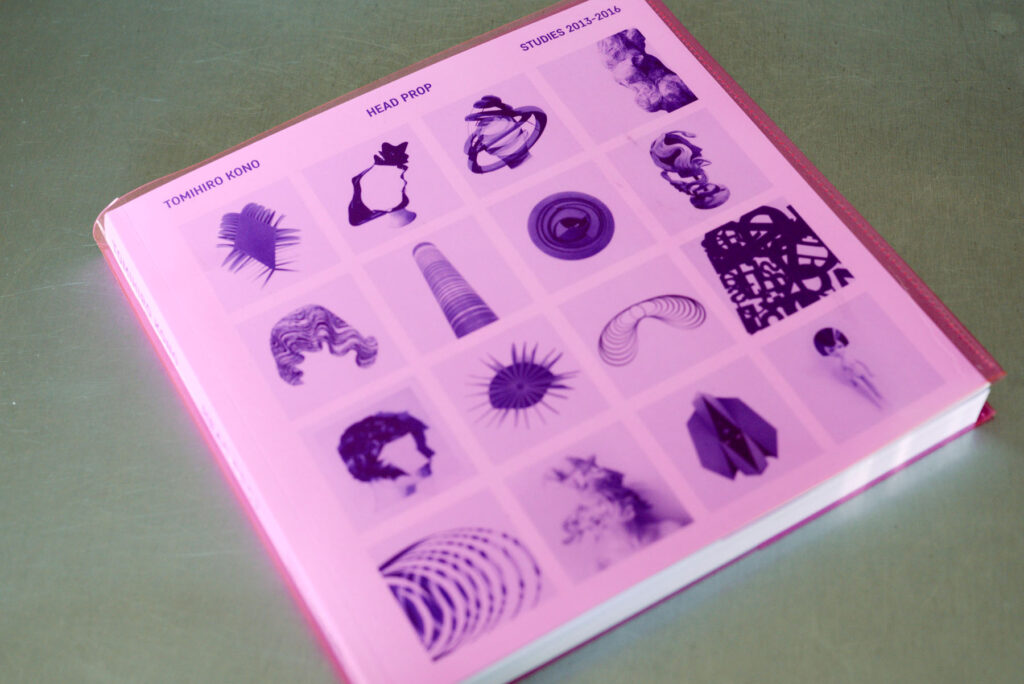

Designers

- Lolo & Sosaku by Cecilia Díaz Betz

- Stellar, 2017

- Studio view, 2020

- Untitled, side A Painting Machine 68cm x 56cm x 10cm x 8cm

- Piano I image by Silvia Poch – Lolo and Sosaku (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1977 and Tokyo, Japan, 1976 ) investigate the possibilities of sculpture as an expanded field. The nexus that unites his works is the search for an object in contact with his surroundings and with the spectator. An object that seeks friction and tension.