«Keep going, don’t stop»

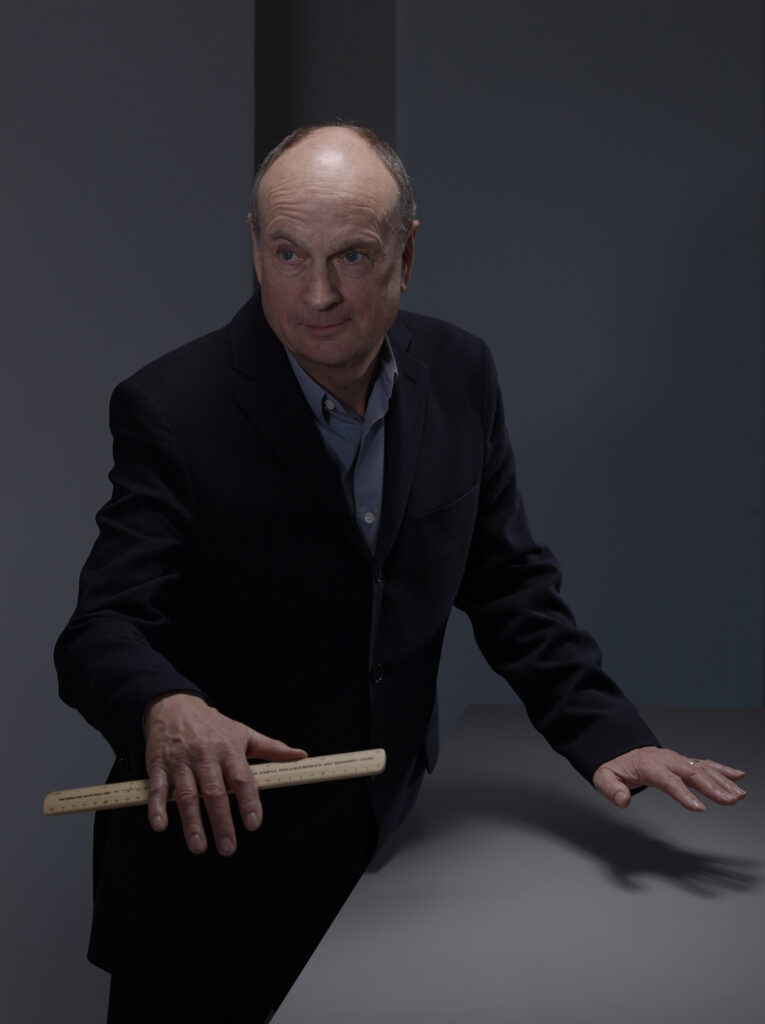

One of the UK’s most influential designers Ben Kelly is perhaps best known for designing the interior of the famous Manchester nightclub, the Haçienda which was infamous in Manchester’s post-punk house and rave scene. Of course, this is only a tiny part of his extensive and varied career. Kelly has worked with big names such as The Sex Pistols, Virgil Abloh, Factory Records, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. However, speaking to him one is reminded of their favourite university lecturer, sternly indulgent and ultimately kind to anyone who falls under the umbrella of the ‘young creative’. He has the interview questions before him, he’s made notes and he asks questions. “What does NR stand for?” “How did you research me?” “What university did you go to and what did you study?”. It’s certainly a novel experience for the interviewer to find themselves becoming the interviewed, and that is only the start as NR Magazines joins Ben Kelly in conversation.

You originally wanted to be an artist before you went into design. If you had stuck to that initial career path what do you think your art practice would look like today?

Well, that’s a simple yet complex question. Who knows what the answer is without having a crystal ball. But when I was applying for my postgraduate at the Royal College I was asked why did I want three more years of further education in the interior design department. My answer was I wanted to discover whether it was possible to mix together art and interior design to produce what I called art interiors. I had equal interests in those two subjects. When you’re a student doing interior design it’s frustrating because you never get to see an end product, it only ever exists as drawings and models. But I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to work with another student to redesign the student bar at the Royal College. I named the student bar the Art Bar and we had a neon sign made saying art bar which is still there today. That’s one of my proudest things that’s been left behind. We went about that project as designers and artists because we had carte blanche because we didn’t really have a client.

Fast forward, I ultimately felt that some years back I had achieved my goal of this combination of references to the art world within the discipline of interior design. Ultimately in the last three or four years, I have produced a number of art installations in 180 The Strand. So I have kind of achieved my goal in a roundabout way. Along that way maybe I was using clients to experiment with this notion of producing what I called art interiors. When we had a looser brief I took that opportunity to investigate those possibilities. I also now operate as an artist in the art world, all be it slightly obliquely, and produce interiors so that’s my answer.

You stated that you are inspired by Marcel Duchamp and that he has «pretty much inspired everyone in the creative world, some way or another.” How exactly do you think he has inspired everyone?

Well, I scribbled down by default. That’s a complicated question but I guess my answer would be that it is an accepted fact, stated by Duchamp himself, that he either intended to or did change the way we look and think about art. If you move that on into the world of design and the broader world it’s unquestionably influenced by the thoughts, approach and activities of Duchamp. I think it’s bled into design and architecture sometimes in subtle, sometimes in obvious ways. It can be almost subliminal. So it’s there under the surface, not necessarily clear or obvious but I believe life had changed generally thanks that one man being on the planet and doing what he did. Without Duchamp, our lives would be different in a quieter way. It would be a poorer world. The thinking behind everything would be different and it would look different. It would lack subtlety and humour.

«Duchamp opened a new toolbox of thought processes and an application of ideas, a new language.»

So historically you go from Duchamp to Richard Hamilton, the artist who reproduced The Large Glass of Duchamp. Hamilton taught at Newcastle School of Art in the late 60s where Bryan Ferry of Roxy Music was a student. Ferry was under the spell of Hamilton who was under the spell of Duchamp. Ferry was equally influenced by Duchamp and the lyrics of his songs related back to him. When I designed the Haçienda I struggled to find a background colour for it because there were acres and acres of walls. I had an idea of that colour but I couldn’t grasp what it was. I eventually found it on an album cover by Bryan Ferry called The Bride Stripped Bare which is a title from a Duchamp artwork. So I enjoyed that connection. I told Ferry about that anecdote and his answer was “I’m glad I could be of help,” and off he trotted.

How has he inspired everyone? By default. By a subtle undertone of influences that other people, other designers, other artists, other thinkers who have drawn inspiration from Duchamp, and that seeps through the cracks.

How would you describe your identity in design?

I don’t and I won’t and I can’t. I like to have an independent identity and not be associated directly with a given description, but I’m interested in the broader description of popular culture. I operate under that umbrella to a degree, but not all the time.

There are two quotes by journalists, which doesn’t answer your question but it sort of does. One is certainly my all-time favourite. In 1982, the same year I did the Haçienda, I did a hairdressing salon on the King’s Road called Smile. Smile was a really fashionable hairdressing salon they started in Knightsbridge and lots of fashion and music people went there. They took this property on the King’s Road one door away from Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s shop. My brief to myself was to design a hairdressing salon that looked the least like a hairdressing salon as possible. In other words, it wasn’t a typical hairdressing salon. So each styling position was different to the next one, they were all different and I used the colour orange. This journalist said, “Ben Kelly rescued the colour orange from the scrapheap of style”. It doesn’t get any better than that as far as I’m concerned.

The other one was about the Haçienda. A journalist referred to it as “the motorway aesthetic”, simply because I used cats eyes and roadside bollards in the scheme. So I leave what my identity in design is for other people to decide. That the job for other people it’s not mine. I just like to be independent and keep pushing boundaries. Going back to Duchamp, I like taking one thing from one world and another thing from another world and putting those two things together that have never coexisted before and suddenly something new happens.

You have stated before that you have been quite angry with people ‘sampling’ your work, but do you think that anyone can create anything truly original in this day and age?

Well, your research has lead you to quotes where I’ve said I’ve been angry or pissed off or whatever and quite a lot of those things I’ve said tongue in cheek. I think I know what specific example is being referred to here. It’s very flattering if people copy your work. However, going back to the Haçienda, (or it might have been the Dry Bar, I can’t remember which one), but within weeks, not that far away, another place opened and it was almost identical to the piece of work we’d done and that pissed me off! It was incredibly opportunist of whoever that was.

Fast forward. I painted stripes on the columns in the Haçienda, merely as a method of making them clear as hazards as they were on the dance floor. So I took the language of factories and workplaces where hazards are marked as per British standard. But that simple gesture I made somehow found its way into popular culture and it’s kinda gone global, you see it everywhere. One person in particular had seen it, someone who became a friend and a collaborator.

«A man called Virgil Abloh put stripes onto garments for a label called Off-White.»

I didn’t know anything about Virgil or Off-White when it was brought to my attention. It seemed pretty obvious where the inspiration for that had come from. It took me by surprise at the time and I was kind of shocked.

It must have been quite frustrating to see that after spending so much time and effort coming up with the ideas.

Well it was just work, and I never thought it would go further than that. Yeah maybe I got pissed off but it took me a while to think about it and understand that it was absolutely no different to what happens with music and the whole idea of sampling. As I’ve said I don’t own copyright on stripes, that would be ridiculous to even think about, but ideas and copyright are so difficult to define. You end up being philosophical because,

«Virgil sampling something I did has paid dividends beyond what I could even imagine.»

It lead on to him and I collaborating, and becoming friends, and opening doors, and making other things possible. Now he’s probably one of the most famous men in the world and that’s not a bad thing to be associated with. It’s a funny old world.

Do you think the idea of copyright and people copying work has gotten more complex with the rise of the internet?

This might sound contradictory I think it had become both more complex and more simple. Because I think we all now understand the idea of sampling. However, copying is a different thing and I will give you a couple of examples. There is a film called 24 Hour Party People which was all about Factory Records, the Haçienda and the whole factory scene in Manchester. It was directed by a man called Michael Winterbottom who I mostly think is a great filmmaker, a man with integrity, but they copied my design of the Haçienda. They had to rebuild it for the film and they approached me for help but as soon as I suggested a fee might be charged they disappeared. The film came out and they did an amazing job but they copied me. That design is my copyright and that’s all designers have. You only have copyright to protect your work so if it’s copied to the millimetre without your permission there’s something wrong there. I spent several years fighting it legally. I wanted to make a big thing about that and take it to the press to make a noise about how important the issue of copyright is but I was so exhausted by the time the distributors of the film settled out of court, I just wanted to let it go.

More recently Manchester City football club have done their version of Haçienda strips on their T-shirts and that really made me very angry. Nobody spoke to me about it and I thought they did a very poor job, I didn’t enjoy what they had done. Of course, they are one of the richest football clubs that there is, so how could I do battle with them? I have to be philosophical and say a bit of a poor show on their part.

So that’s the way it goes with copyright and sometimes it’s relevant and sometimes it isn’t. You have to be careful and young designers do get their work copied, particularly in the fashion industry. I don’t think that young people are sufficiently aware of how to protect their work. I always wanted to make a noise about it but I was exhausted and wanted to move on. However, I make reference to it where I can, like now, to bring awareness.

How has designing the Haçienda influenced your design journey and ethos?

That’s a huge question for me. The Haçienda opened in 1982. Next year it will be the 40th anniversary of the opening.

«My quote is the ‘Haçienda never dies’, and it doesn’t.»

Its influence and story, it’s embedded in popular culture. It’s been acknowledged as one of the most important nightclubs for a whole host of different reasons. However, for me at first, it became the monkey on my back. It wouldn’t go away and people would only talk to me about having designed the Haçienda. Of course, I’ve designed many things, many different types of interiors, and many other things outside of interior design, and that kind of annoyed me. Then I stopped being annoyed and realised that it was a massive asset to me.

My interpretation of your question is, having designed the Haçienda, the slipstream that followed on from it has massively influenced, and lead on to, the majority of work I’ve done ever since. I could say possibly 99% of what I’ve done since, in one way or another, there have been references to the Haçienda, or it happened as a result of Haçienda, or some intersection of those. Something to do with the Haçienda has been a part of nearly every project I’ve done since. That might not be visible or legible or understandable but I know it’s embedded in there somewhere. So that’s fed into work I’ve done in many other disciplines, it’s been a big part of what I’ve done.

You worked on the set design for the PTB19 runway show. How do you see interior design and fashion working together in the future?

Again with that project they came to me because the collection they showed had been partly inspired by the design of the Haçienda. For the set, there are subtle references to the design of the Haçienda which are

mostly some black and yellow stripes. I’d like to think it was done in a poetic and subtle way. It was great I really enjoyed doing that show.

But to answer your question, I have no idea, I can’t predict the future. Well, going back to Virgil, his last Off-White show was done virtually because of the pandemic. My observation was that he’d taken his inspiration for the set from a combination of two interiors. One was was The Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe. The other was a set from 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick. So obviously you get this really heavy mix of references which is a kind of Duchampian. I know that Virgil, is as obsessed with Duchamp as I am, it’s something we share. So fashion and interiors, there’s no limit to that collaboration. I expect to see really rich pieces of work coming out of that combination of design disciplines and industries. People like Virgil are in the luxurious position of leading the way because they have big budgets and can work with the best people in the world.

But if you put all that to one side and bring it back to young people, who’ve left college and are trying to find a way of being creative, that’s where my interest lies. The future belongs to them and it’s the hardest environment to be operating in right now, my sympathies lie hugely with young people. But finding a space, finding backers, finding a budget, being able to just go to a nightclub, is almost unaffordable.

«To buy a drink in a bar is almost unaffordable so new ways have to be found. They have to be super creative, and sidestep the mainstream and find another way.»

That’s why punk was so great, it was two fingers to authority and invent your own ways of doing things. It didn’t last that long but the spirit and the ethos of it is still there. I’m looking forward to the revolution.

Has Covid affected how you approach your art practice, and if so how?

Well yeah, that was interesting when covid hit and the lockdowns and the poor handling of it by our government. I’m very lucky because I’m sat here talking to you from my studio in London, but I have another, bigger, studio on the south coast. So I went and isolated down there and the phone stopped ringing, well it’s emails and texts these days, but that all stopped and went quiet.

I had been asked to design a piece of artwork as a print, but the pandemic put a stop to the exhibition happening. So I’m sat there in my studio and I thought “I won’t make it as a print, I’ll make it as a painting”. It was to do with the language of the Haçienda, and I thought “Oh I could do another one” so then I did another one and another one, and I did maybe fifteen or sixteen of these paintings over the first and the second lockdown period. It was fantastic, it was like therapy, it was another form of expression. I’m hoping that some paintings I’ll be able to show in an exhibition. So the pandemic physically affected my art practice in that it made me sit down and make some paintings which I enjoyed. It will lead on to me doing more of that kind of work. Something that I independently drive forward, there isn’t a client or a brief, it’s just me. So I have the pandemic to thank for that.

What advice do you have for young creatives looking to work in design?

Be independent, is my advice. Keep going, don’t stop. Mistakes will be made but you learn from those mistakes. You will fail at things, but failure teaches you an awful lot. When I started it was so much easier, because my first projects were done for people who were friends or like-minded people. Now it’s much more complicated because everything costs more money, there’s less money around and the internet changed everything. We need to find a way for young people to operate. For young creative people in the art world to find space to do what they do and add richness to our lives.

«Richness is being removed, the oxygen is being sucked out, and we need to fix that.»

Are you working on any projects at the moment and what plans do you have for the future?

Well, two things. I have done a collaborative project with a photographer called Eugene Schlumberger. Using Kickstarter we have funded a book called Haçienda Landscapes. The story there is I stumbled upon his work on Instagram. I kept seeing these photographs that I thought were really beautiful and really just compositionally well thought out and I realised that they were referencing the Haçienda. This guy was finding the language of the design of the Haçienda out in the post-industrial landscape in the North-East of England, with all the ruined factories and machinery with hazard stripes. I messaged him, we started talking to each other and eventually met up in London. I said we need to do a project together and it should be a book called Haçienda Landscapes. I’ve also been taking photographs over the years of things that kind of reference the language of the Haçienda but mine were more snapshots. His are quite thought out, carefully composed and it makes a really nice kind of contrast with these two different sets of photographs. We’ve been very successful so I hope we are going to produce a thing of great beauty. The other is an exhibition at 180 The Strand which has turned into the most amazing alternative art space. The owner of the building is someone I’ve known for a very long time and they’ve commissioned me to do a couple of installations there. It’s going to be called ‘Columns, Revolving Mirrors and International Orange’.

Credits

Images · BEN KELLY