Dark Pink

SANTIAGO, CHILE — Elisa Garcia de la Huerta was born 1983 in Santiago, Chile and is an interdisciplinary artist.

She received her BFA at Universidad Finis Terrae, Chile in 2006 and her MFA Fine Arts at the School of Visual Arts, New York in 2011. She was also co-leader of Go! Push Pops a queer, transnational feminist performance art collective until 2017. Elisa has shown her art/performance at the Brooklyn Museum, Bronx Museum, Whitney Museum, Untitled Space, C24 Gallery, Momenta Art and Soho20 Gallery in New York, USA and Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Museo Historico Militar, Galeria Artespacio in Santiago, Chile as well as Select Art Fair for Miami Basel and Busan, Korea among others. She has been nominated for the Rema Hort Mann Visual Arts Grant, has obtained a Brooklyn Arts Council Grant and the Culture Push Fellowship for Utopian Practice with Go! Push Pops. Her work has been featured in New York New Wave book by Kathy Batista, Vice, Dazed and Confused, Bowery + Bedford, ART 21 Magazine, Cultura Colectiva, Frontrunner, Nakid Magazine, SHE/FOLK, Huffington Post, Japan Times, BUSTLE, ArtSlant, Slutist, Hyperallergic, The Wild Magazine, NY Observer, Paper Magazine, Interview Magazine, Milk Media, Art Fag City, Art Net TV, Bushwick Daily, BOMBlog, CatchFire, BronxNet TV, Abiola TV, El Mercurio, Mas Deco, Artishock and Arte al Limite Magazine. Garcia has been an Artist-in- Residence at Alexandra Arts in Manchester, UK, 2015, Soho20 Chelsea in NYC, 2012, The Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, 2013 as well as in Havana, Cuba 2003 and London, UK 2007 and performed in Tokyo Japan with Go!PushPops as part of US/Japan exchange fellowship in 2015.

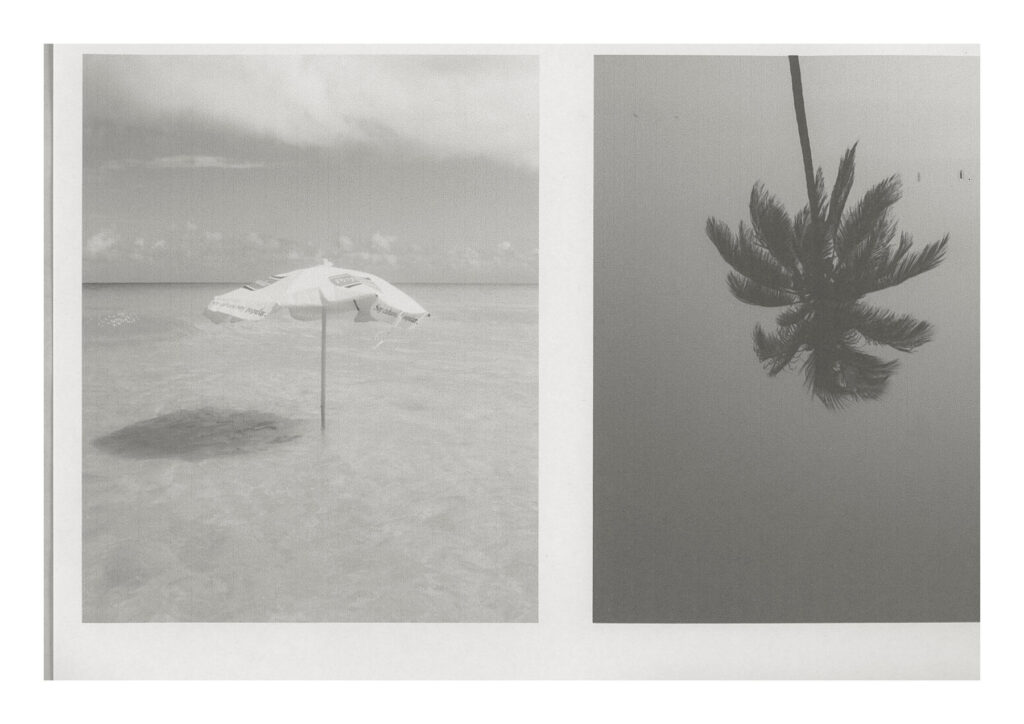

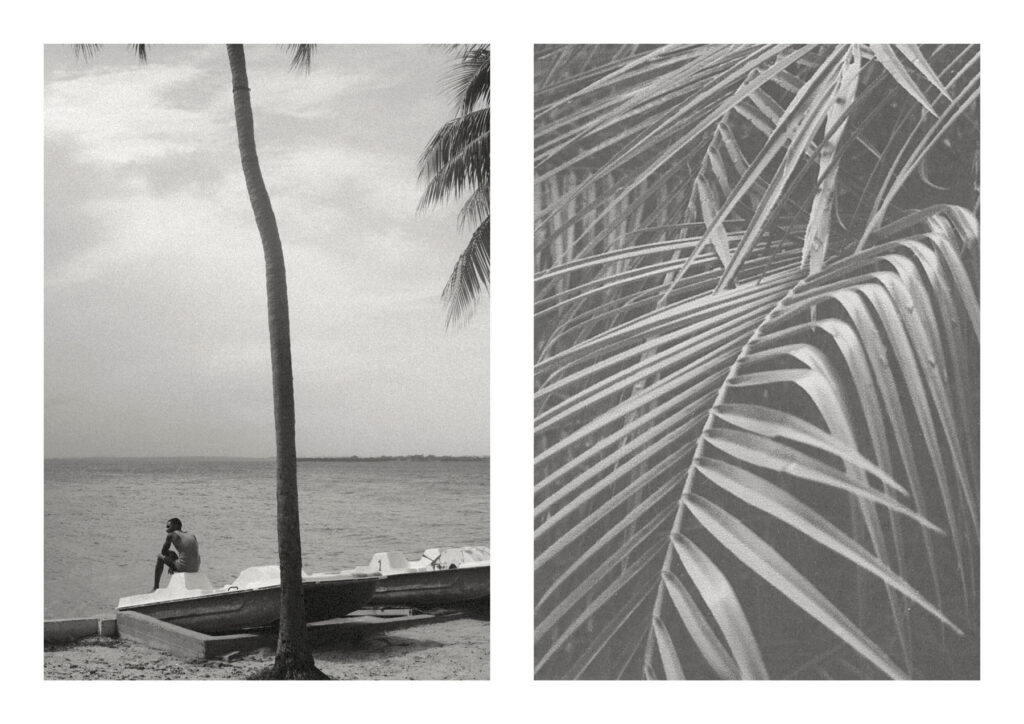

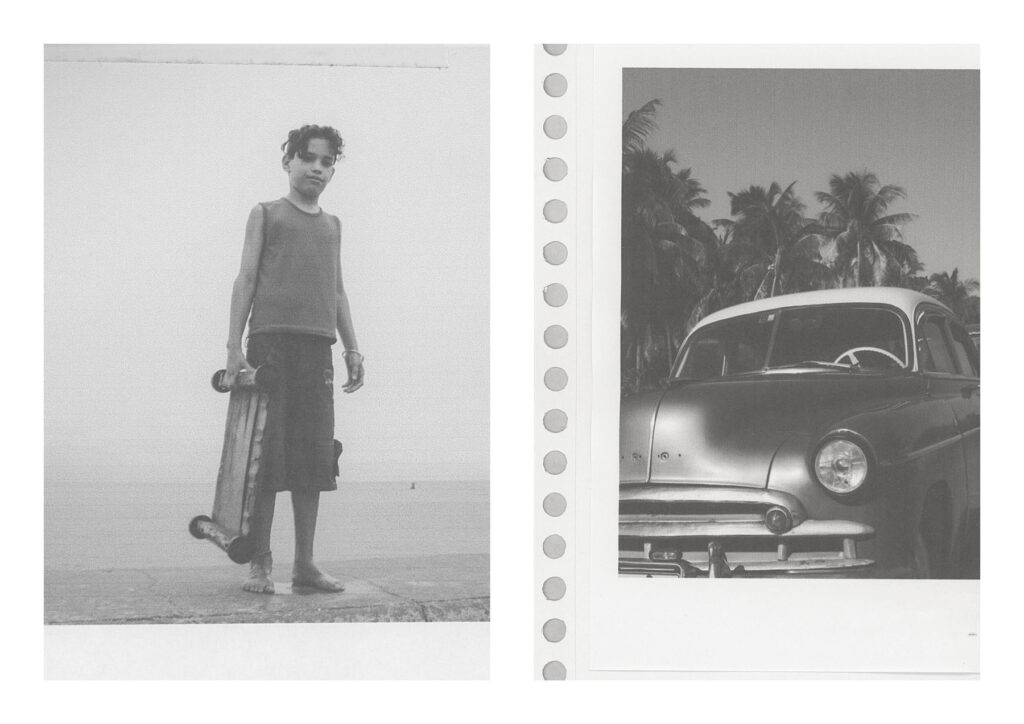

She did a course in Sonic Arts at HAMT in Dharamsala, India with Michael Northam in 2019, was artist in residence at Backsteinboot (ex Modular + Space) in Berlin, and she focus on fine arts analog photography and sound performance.

Credits

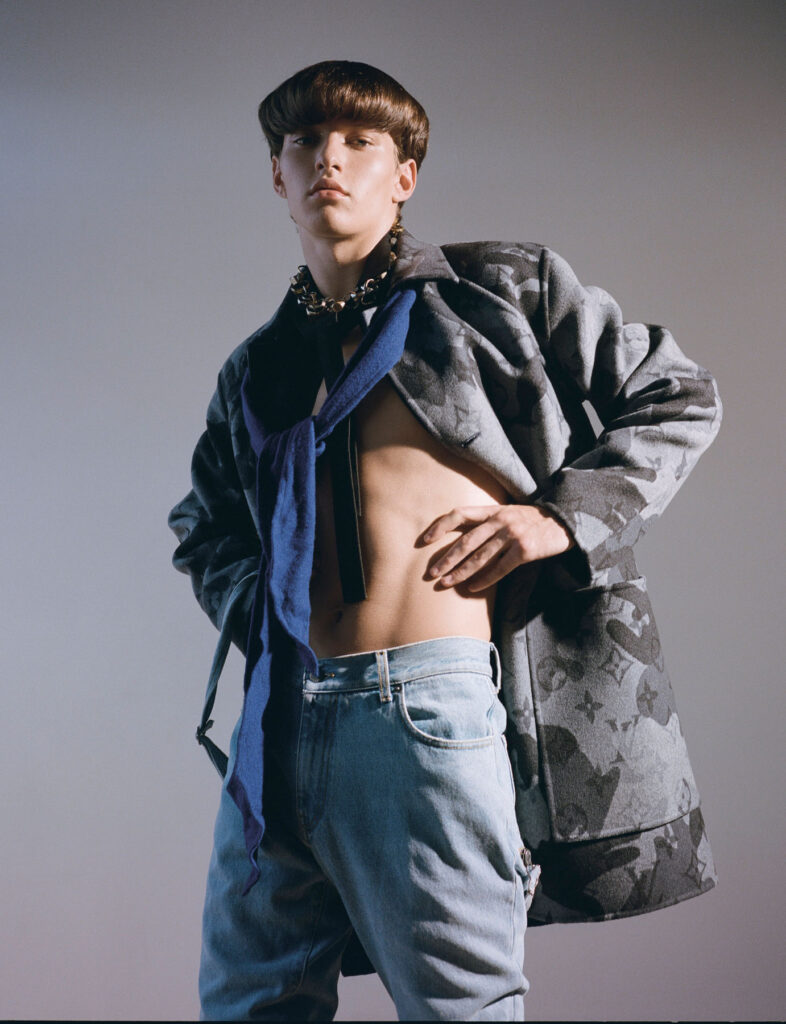

Photography · ELISA GARCIA DE LA HUERTA

www.instagram.com/auzit

www.elisaghs.com

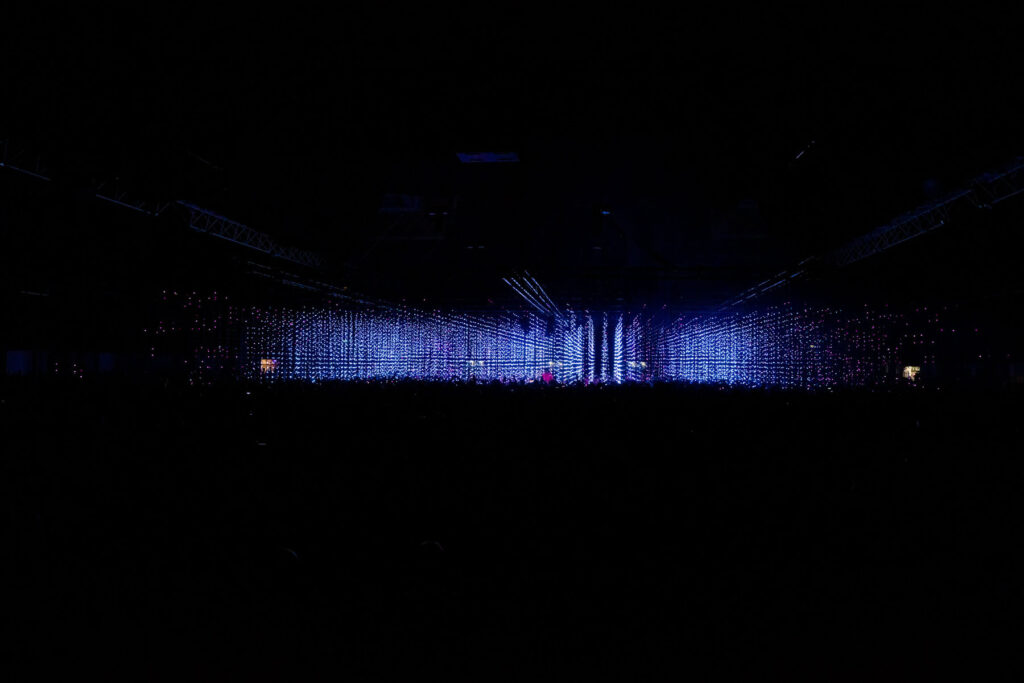

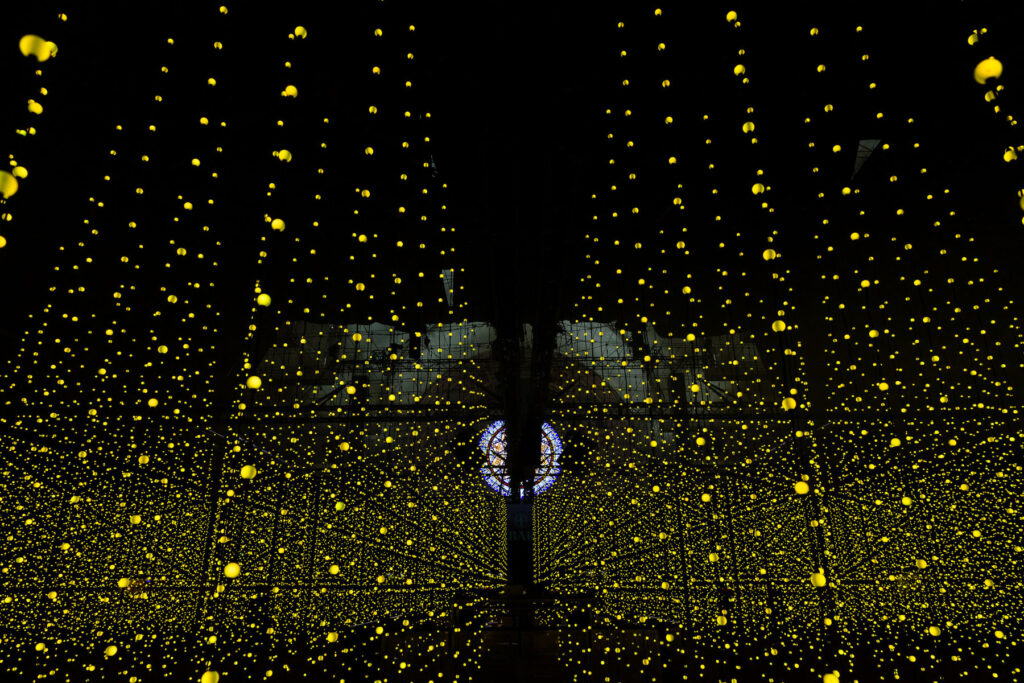

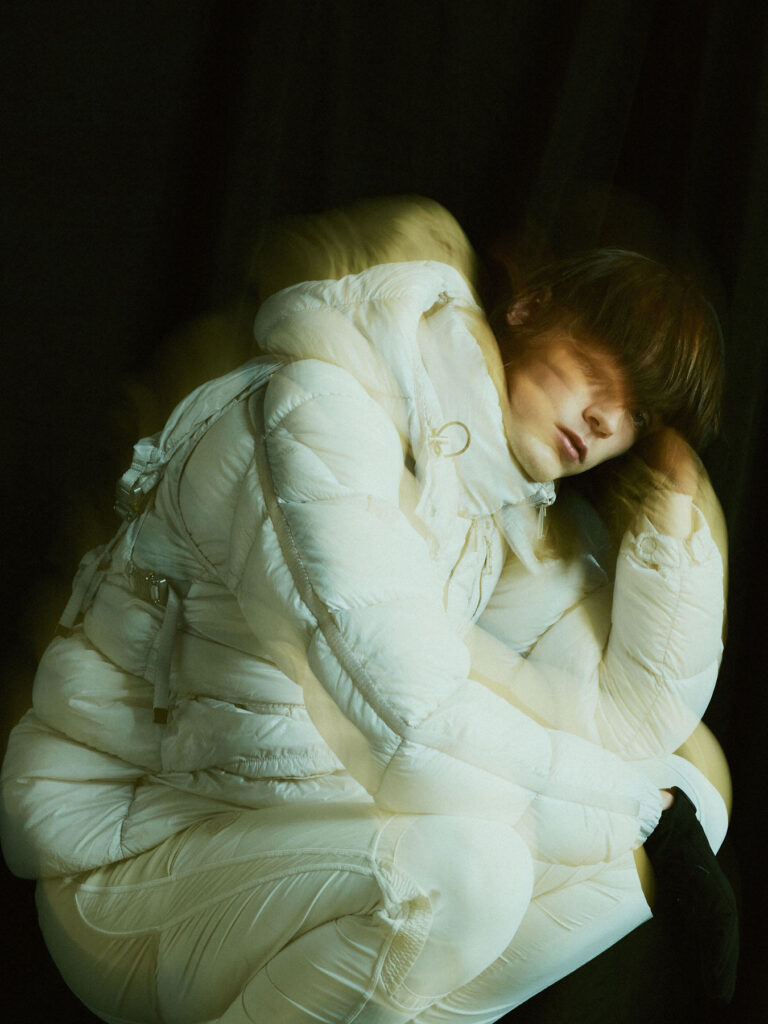

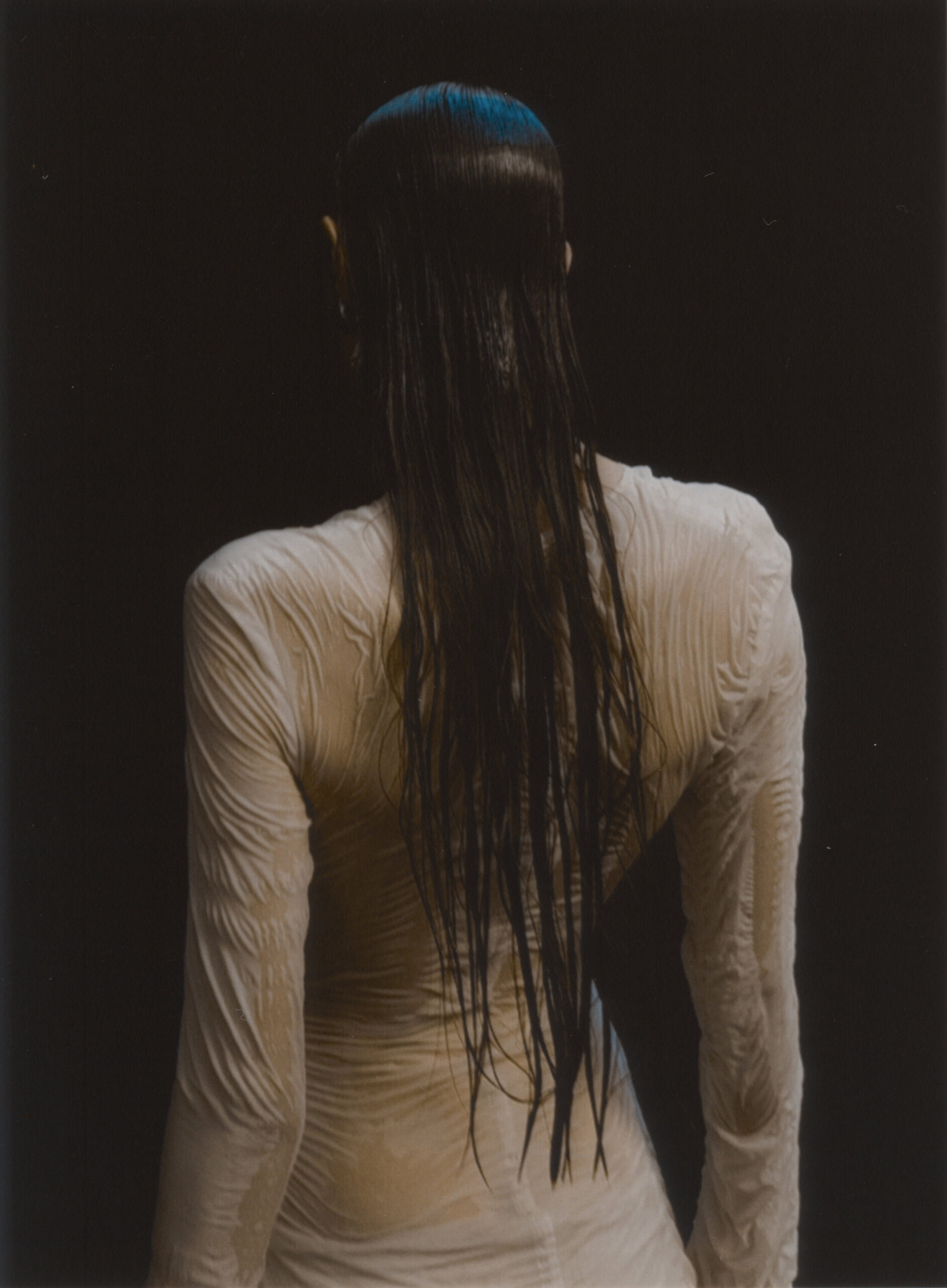

Photos

- Dida, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Daniela, Baile, 35mm 2020

- Pink Bath, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Pauli Cakes, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Rachael Uhlir, Spandau, 35mm, 2019

- Daniela, Chile, 35mm, 2020

- Beauty Thorns, Chile, 35mm, 2020

- Manos, Faraona, Chile, 35mm, 2020

- Snake por Raz Pinto, Faraona, Chile, 35mm, 2020

- Dida, hardpink, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Sunset, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Rita, Temphelhof, 35mm, 2019

- Botanica Nipple, Melanie, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Spiral, Andrea, 2019

- Cristina, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Sex, Berlin, 35mm, 2019

- Merle’s hands, 2019, Berlin

- Merle, 2019, Berlin

- Self Portrait, Brooklyn NY, 35mm, 2018