Navigating Through Life

Ai Weiwei (b. 1957, Beijing) is undoubtedly one of the most influential and fearless voices of our time. In a world where the right to express oneself is often taken for granted, Ai Weiwei’s unwavering commitment to this cause emerges as a clarion call to create inclusive spaces where every voice is respected and cherished. “Expressing oneself is a part of being human. To be deprived of a voice is to be told you are not a participant in society; ultimately it is a denial of humanity”. A statement followed through by the immense outspoken nature of what Ai Weiwei’s body of work testifies to be. As he beautifully puts it in this interview, without free expression, we lose our expressive uniqueness, “akin to flowers that fail to bloom, birds that cannot soar, fish that cease to swim, and clouds that no longer drift across the sky.” Ai Weiwei’s art transcends mediums, seamlessly merging with activism in works like Remembering (2008) and Human Flow (2017) where he sheds light on the plight of refugees, compelling us to take action and empathize with those in dire need.

His exploration of cultural heritage, craftsmanship, and the value of everyday objects in his latest exhibition at the Design Museum in London serves as a testament to his enduring commitment to preserving our shared history. Our conversation with Ai Weiwei also delves into his relationship with technology and social media, illuminating the complexities of online engagement in a world marked by censorship and rapid change. He offers his perspective on the evolving role of design in contemporary society and reflects on his deeply personal connection to the objects he collects.

In this interview, Ai Weiwei also delves into how his journey with his father, Ai Qing, not only shaped the man he became but also paved the way for the unique connection he shares with his son. Standing at a crossroads of generational wisdom and personal growth within the complexities of parenthood, identity and the world he envisions for the next generation, Ai Weiwei finds himself tasked with the delicate balance of imparting the lessons of his past without allowing them to cast a shadow on his son’s future.

Ai Weiwei shares not only his artistic vision but also his unwavering commitment to the values of human rights, freedom of expression, and the enduring power of art as a force for change.

Jade Removille: Ai Weiwei, it is a pleasure to be able to have you as part of this upcoming issue. Where are you now?

Ai Weiwei: I am in London at the moment, but my residence is in Portugal.

Jade Removille: On your website’s homepage, the powerful statement “Expressing oneself is a part of being human. To be deprived of a voice is to be told you are not a participant in society; ultimately it is a denial of humanity”, urges society to create inclusive spaces where everyone’s voice is respected and honoured, reinforcing the notion that self-expression is not just a privilege but an essential aspect of our shared humanity. As an outspoken dissident artist and a fervent activist for human rights, could you delve into how significant self-expression is to you?

Ai Weiwei: Thank you for your insightful interview question and for taking note of my comment on free expression. Free expression is often perceived as a core element of human rights. In a deeper sense, without free expression, each individual loses their unique attribute that belongs to them. If such circumstances prevail, our society would be robbed of its expressive features, akin to flowers that fail to bloom, birds that cannot soar, fish that cease to swim, and clouds that no longer drift across the sky. Such a world is indeed a daunting prospect.

Free expression facilitates our ability to perceive the world as an extension of our senses and emotions, enabling the manifestation of our unique perspectives. It is through this individualized articulation that we can truly appreciate the richness of human nature and the value of our shared humanity.

In my view, free expression is not exclusive to artists or to those who construct foundational thinking paradigms. Rather, it is the most crucial element that defines us as human beings. Stripping away the right to free expression is perhaps the most damaging action against individuals, as it strips away their very essence.

Jade Removille: Has your sense of belonging to China been undermined since your exile in 2015? Have you found your oasis of peace? Do you see a future in which you would come back?

Ai Weiwei: My sanctuary of serenity resides solely within my heart. Much like a diligent gardener, I continually tend to my personal thoughts and expressions, nurturing them so they can flourish. It would be accurate to describe me as a person without a homeland. From my birth, my father was deemed an enemy of the state, so I grew up in exile within my own country during my early years.

Subsequently, I embarked on a journey abroad, having lived in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Portugal. None of these places can be referred to as my hometown. My maternal language is Mandarin Chinese, which makes my existence in these foreign lands akin to navigating life with a disability, relying heavily on body language and gestures to barely communicate. Nevertheless, I am profoundly grateful to these countries for providing me with opportunities to engage with issues that matter to me and to remain active.

Jade Removille: At 15 years of age I was introduced to your work through the Sunflower Seeds installation in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern (Kui Hua Zi, 2008), and it left a lasting impression on me. I remember my parents and I were utterly amazed by the meticulous craftsmanship of the seeds, their delicate nature, and the sheer scale of the installation, which was difficult to fathom. In an interview for Tate, you mentioned that sunflowers symbolised the revolution, providing both spiritual and material support for the people. The immense quantity of seeds created for Tate Modern was unimaginable, yet you accomplished it. Witnessing such a meaningful installation also benefiting and providing employment for the hundreds of artisans involved was truly moving. Could you talk more about this work? Did you plan on the installation to interact in a specific way with the location and the visitors?

Ai Weiwei: Thank you for sharing your experience of encountering this artwork as a teenager. I must confess that I also first saw this installation in its entirety at Tate Modern. At that moment, my feeling was the same as yours.

When an artist embarks on creating an artwork, it begins merely as a concept. The particular characteristics of this concept were its grand scale and voluminous nature. What is more important is that these 100 million sunflowers were each meticulously painted by hand by 1,600 women. These women, dedicating two weeks of their lives to this project, rendered it almost a religious activity of a kind of daily expression. The sunflower seeds are the embodiment of their craftsmanship.

In Jingdezhen, the town of these women, this is their tradition as well as a means of survival. Concurrently, their straightforward task of painting sunflower seeds encompassed a profound sense of interest and engagement. This imbued me with a feeling of the enduring power of art. It doesn’t simply draw people’s attention, but its creation is also a testament to the investment of time, the grandeur of volume, and the concerted labor of many hands.

Jade Removille: I would like to address your practice as an architect. You used to run FAKE Design with which you realised 60 projects. FAKE closed down shortly after the Olympic ceremony for which you had designed the Bird’s Nest’s stadium in collaboration with Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron. Your involvement in this project helped to shape its iconic and innovative structure. You brought to architecture, the humanity it needed but you have mentioned before that you had had enough of it. Why does this medium not suit you anymore?

What was your very first architecture project?

Ai Weiwei: My first architectural project occurred before I even recognized it as such. It was when my father and I resided underground, in a ‘diwozi’, devoid of electricity and water. Our bed was merely a platform left from the excavated earth, topped with straw. Our only source of natural light was a small window above. Occasionally, pigs would pass by, sometimes partially sinking through and hanging halfway from our ceiling before scampering off in panic. That was our reality.

Amid these circumstances, I needed a place for a lamp. We carved a small square hole, around 20cm high and 30cm wide, where we placed our oil lamp. This humble hole, dictated by the constraints of our environment, has left a strong impression on me. I hadn’t realized it then, but it embodied an essential element of architecture: providing solutions for our fundamental needs in the most basic ways. Such solutions can range from a modest hole for an oil lamp to a colossal stadium meant for an entire nation.

The year we completed the National Stadium was also when I decided to abandon architecture. I came to realize that the application of architecture wasn’t based solely on individual desires but could be manipulated as a tool for national propaganda. I felt a sense of regret for our work. Despite creating an ambitious and unparalleled piece of public architecture for Beijing, its usage contrasted starkly with our original aspirations. It became a symbol of power projection and a mechanism to sideline individual existence. That’s why I chose to step away from this highly politicized practice.

Jade Removille: Intensity, care, resilience, memory and recovery in the face of immense destruction are recurrent threads in your work. With Remembering (2009) at the Haus der Kunst museum in Munich, Germany, 9,000 backpacks were arranged to display a quote in Chinese characters that read, “She lived happily for seven years in this world. Each backpack in the installation represented a life lost in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China, particularly the young students who perished due to the collapse of poorly constructed school buildings.

In your 2015 exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, you had created a striking and thought-provoking installation using 90 tonnes of steel bars salvaged from the debris of the earthquake. Each steel bar was meticulously straightened by hand, a labor-intensive process that imbued the artwork with an additional layer of meaning and significance.

Through your work I sense that part of your message is conveying the indomitable spirit of affected communities and their ability to rebuild. How do you think governments could be held more accountable on systemic issues and what is our role in this?

Ai Weiwei: My focus on straightened rebars as artworks emanates from a deeply personal place, as they are connected to the lives tragically lost during the 2008 earthquake. Uncovering their names and identities became a necessity. Yet, such simple and concrete facts can often be brushed aside and forgotten in some societies. In my view, neglecting our shared memories and disavowing our communal sense of guilt for the disasters of the past render us accomplices in evil. Consequently, if we believe in our right to seek freedom, expressing human rights equates to our duty and obligation to remember those who have been hurt and forsaken. Such endeavors serve to constantly remind us not to devolve into beings devoid of feelings and a sense of justice. The recollection of past experiences, the understanding, and empathy require a language and means of expression. My artworks are an exploration for such a language.

In terms of whether my artworks strive to hold governments accountable for disaster management, I feel that I have failed. My artworks only represent what I, as an individual, can accomplish, in tandem with those who resonate with my cause. They do not appeal to the government, which is not a single entity but a complex mechanism operating on the principles of bureaucracy and power. More often than not, the governmental understanding of human life and rights stands in stark contrast to our own. This dichotomy underscores the necessity for every individual to voice their perspectives.

Jade Removille: You touch upon interconnectedness of life and art, how art is about life and its reality. Art becomes a means of activism. Human Flow (2017) your film about the refugee crisis is a poignant call for action. Had you always thought about the role of art or the role of an artist in this way? How far do you take art as a means of activism?

Ai Weiwei: My interest in the refugee crisis stems not from the principles of activism, but from my desire to comprehend the world more deeply. When I left China in 2015, my understanding of global issues was rudimentary, superficial even. I needed a pressing international event to deepen my insights. Consequently, I immersed myself in the refugee issue over the following years.

I traveled to numerous countries, visited countless refugee camps, and conducted interviews with hundreds of refugees and the volunteers aiding them. These experiences culminated in several films and provided me with an understanding of the political landscape in the context of globalization. Whether as an individual, an artist, or an activist, the labels don’t matter. What truly counts is how I use my limited time to acquire a comprehensive and balanced understanding of humanity as a collective and the world in which we reside.

The formation of such understanding requires the assistance of both activism and art. Without activism, I wouldn’t have the opportunity to engage firsthand and experience these situations deeply. Without art, my involvement wouldn’t find an adequate channel for expression and release.

Jade Removille: You place great value in the past and artefacts and throughout the years you have researched history, ideologies, materials and artistry. Within your work there is an embrace of the handmade and reverence for craftsmanship in an era in which automation and mass productions are revered. What does destruction of cultural heritage mean to you?

Ai Weiwei: Humankind is hurtling at an unprecedented pace towards accepting new realities, a process that demands the hefty price of forgetting our roots and striving to erase our most innate attributes. These original attributes encompass our need to employ our hands in work and our feet to gauge distances – aspects now largely replaced by technology. Consequently, we no longer actively use our hands as we once did. Our hands, once vital and irreplaceable extensions of our creativity and thinking, thus becomes disconnected and irrelevant to our struggles and understanding of the world.

In this light, human nature is evolving because the functions of the human body are changing. This leads to shifts in human logic and language. It is why I persist in believing that we must retain these basic abilities – not only do they ensure our survival, but they also imbue our thought processes with meaning.

Jade Removille: Your new exhibition Ai Weiwei: Making Sense at the Design Museum, London explores the value of everyday objects, from ancient stone-age tools, fragments of pottery from your Beijing studio (which was demolished by authorities in 2018), as well as an impressive collection of approximately 100,000 ceramic cannonballs and 200,000 broken spouts from teapots or jugs. You have said we are products of our time, giving new interpretation based on their own knowledge. What does design mean to you in relation to our time now?

Ai Weiwei: Whether intentional or not, design has always primarily been a reflection of one’s identity, and subsequently, it communicates our collective identity to others. To truly comprehend who I am and who we are, we must delve into our understanding of history, our origins. It is only by acknowledging where we come from that we can grasp our present state. As for where we are headed, that remains uncertain.

What we possess are the history and memories that have shaped us, the processes that have defined our identities. Our understanding and recollection of history, our awareness of various conflicts and contradictions, these are indeed what will form the foundation for who we might become in the future.

Jade Removille: What was the first object you consciously decided to collect and why?

Ai Weiwei: In fact, I’ve never regarded myself as a collector. In the society where I grew up, there was no private property or personal ownership; everything we possessed, including our thoughts and individual actions, belonged to the state, to be assessed by its standards. The only possessions I could call my own were my early memories.

Upon my return to China, I found many items that I deemed valuable casually for sale in markets and on display, without anyone paying much attention. These items included Neolithic stone axes, spouts, and porcelain balls. My impulse to collect them stemmed from the belief that the sheer volume of my collection could serve as tangible proof of our collective disregard for our own history and the values it embodies. It reflects our blindness to the foundations of our existence.

Jade Removille: All this materiality and collectibility contrast highly with a sense of having survived at some point with nothing but yourself, your mind and your health. How has your self-perception in relation to the collective evolve after remaining isolated in secret detention for 81 days, in 2011?

Ai Weiwei: We arrive in this world bare, and equally bare shall we depart from it. All our collections merely signify our deep affection for the people and things in this world, or perhaps, a certain curiosity. However, these are attachments we can’t carry with us in birth or death. They are public resources, yet under many circumstances, they must be understood and curated by individuals.

When I was secretly detained, my loss was not simply of the items I had collected. Instead, I was deeply affected by the reality that everything lost its meaning because I was isolated and could not communicate or exchange with others. This included memories, which also lost their significance, as they are resources meant to be shared and utilized by the public. That’s why I embarked on writing my memoir immediately after my release, even though it took almost a decade to complete.

Jade Removille: Which specific places in the world have had a profound impact on you and left a lasting mark? How have these places helped position yourself in relation to the collective?

Ai Weiwei: To be frank, my travels have taken me to many places, driven by work or personal curiosity. Yet, the place that has had the most profound impact on me is one I hadn’t appreciated for many years – the ‘diwozi’ where I moved in with my father as a child. Out of all the places I have lived, the ‘diwozi’ holds the greatest significance. It was there that I came to understand common human nature, the value of things and political idealism, which has enabled me to stay alert and aware to this day.

Jade Removille: As a keen user of technology and social media, to which extent do you think you are reaching a level of connectedness with your audience? Do you feel more free online?

In these recent days we have been seeing the introduction of a new social media platform. Will you be using Threads?

Ai Weiwei: In my time in China, I initially believed that social media could help us overcome communication difficulties, censorship, and restrictions on expression. However, my experiences soon revealed the absurdity of such a notion. Today, social media in China operates under severe political censorship, leading to a limited form of expression. It manifests as a peculiar form of media—altered by power, favoring entertainment over depth, serving as a platform that lacks profound expression. In the West, social media isn’t entirely free either. It’s akin to a bustling disco, where the clamor, the overarching melody, and the rhythm still dictate the overall environment. I don’t perceive social media as a medium for deep thinking. Its real strength lies in serving as an information channel and fostering a diversity of expression. It enables us to experience a time, unimaginable prior to its advent—a time imbued with mythical connotations, feelings, and expression. As for its impact on societal development, I believe it merely accelerates society’s existing trajectory. Be it politically or economically ascendant or descendent, social media hastens the pace.

I’m not familiar with Thread; I’ve only recently heard of it. My requirements for social media are akin to my needs from a pair of shoes. I wouldn’t purchase a new pair simply because it’s available, not until my current pair is beyond use.

Jade Removille: Which other artists inspire you?

Ai Weiwei: In my younger years, I found inspiration in Duchamp, the artist who shattered the barriers of conventional thought. Alongside him, I regarded Andy Warhol as a pioneer in the realm of communication and artistic expression.

Jade Removille: What does process mean to you and what does the finalisation of a project bring to you?

Ai Weiwei: To me, process signifies everything. Life, from birth to death, is a continuous process. The completion of one project merely marks the inception of another. Until our final breath, nothing is ever truly finished.

Jade Removille: Looking towards the future, which current projects are you working on? What do you wish to learn more of?

Ai Weiwei: First and foremost, I don’t believe I possess a future. I don’t hold any grand ideals or ambitions either. My desire is simply to navigate through life with greater serenity and tranquility.

Jade Removille: Finally, the theme of this issue is Personal Investigation. In your memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, 2021, you delve into your personal experiences and shed light on the events that unfolded in your life and that of your father, Ai Qing, a significant figure in Chinese literature. Drawing parallels between your own journey and that of your father, who faced challenges in his time, you were also finding yourself a father to a two-year-old son. Considering this context, could you share your reflections on the intergenerational impact of personal experiences and how they shape your role as both an artist and a father? How do you navigate the complexities of your own life while also contemplating the kind of world you want your son to inherit?

Ai Weiwei: When my father was alive, our father-son relationship was largely unfamiliar to me. I bore the brunt of the calamities my father brought upon our family as a writer and thinker; these adversities were shouldered by us all. Our relationship was always fraught with complexity. My father never envisioned us becoming a thinker or artist, mainly because it was evident that such individuals often brought immense hardships to their families. As I strove to extricate myself from these political chains, my efforts persisted for decades. Throughout this time, I never considered starting a family or having a child. However, when my son turned two and I was secretly detained, I began to realize that my understanding of my father was quite limited. I also acknowledged the responsibility I had towards my son, namely, the obligation to pass on what had transpired between my father and me. This was necessary because there was always a risk that I could perish at any moment, and it would be a shame if I didn’t fulfill this duty. The relationship I had with my father shaped the one I have with my son. I don’t want him to be influenced by me at all, as he will face a time and lessons utterly different from my own. However, I also don’t want him to forget his roots. My son is now 14 years old, and I must carefully consider how to prevent my experiences from negatively influencing him.

Images

- STUDY OF PERSPECTIVE: TIANANMEN SQUARE, 1995-2011

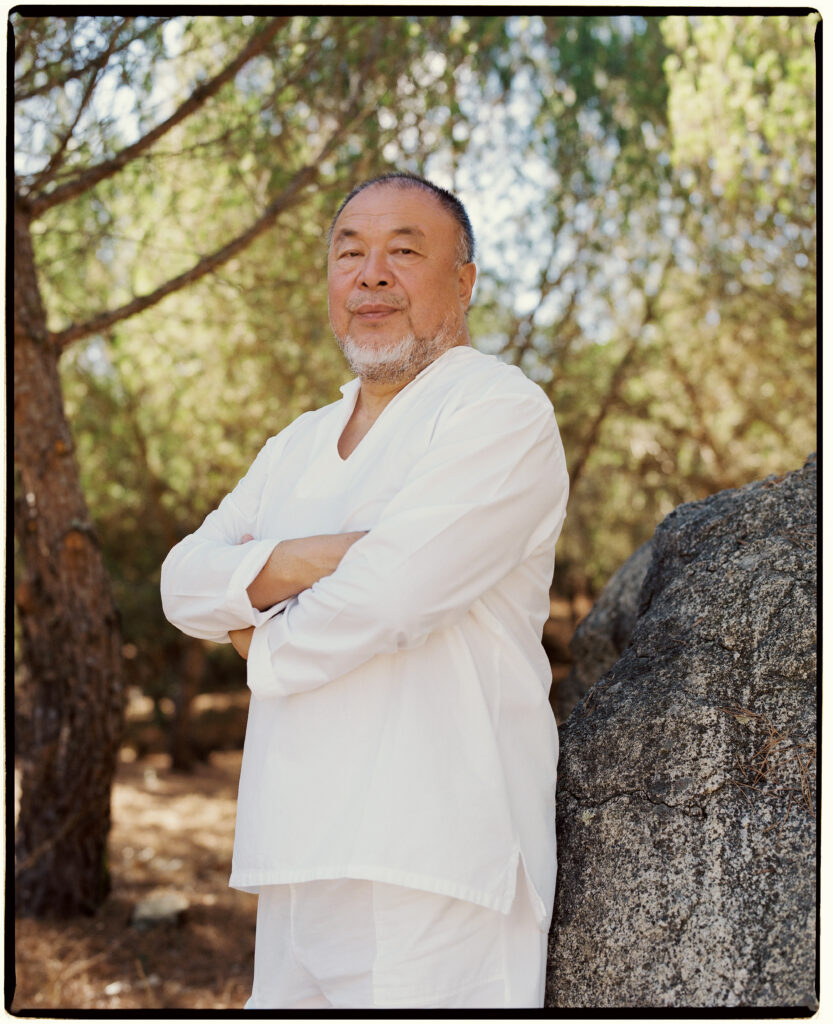

- AI WEIWEI PORTRAITS Photographs by Luba Kozorezova

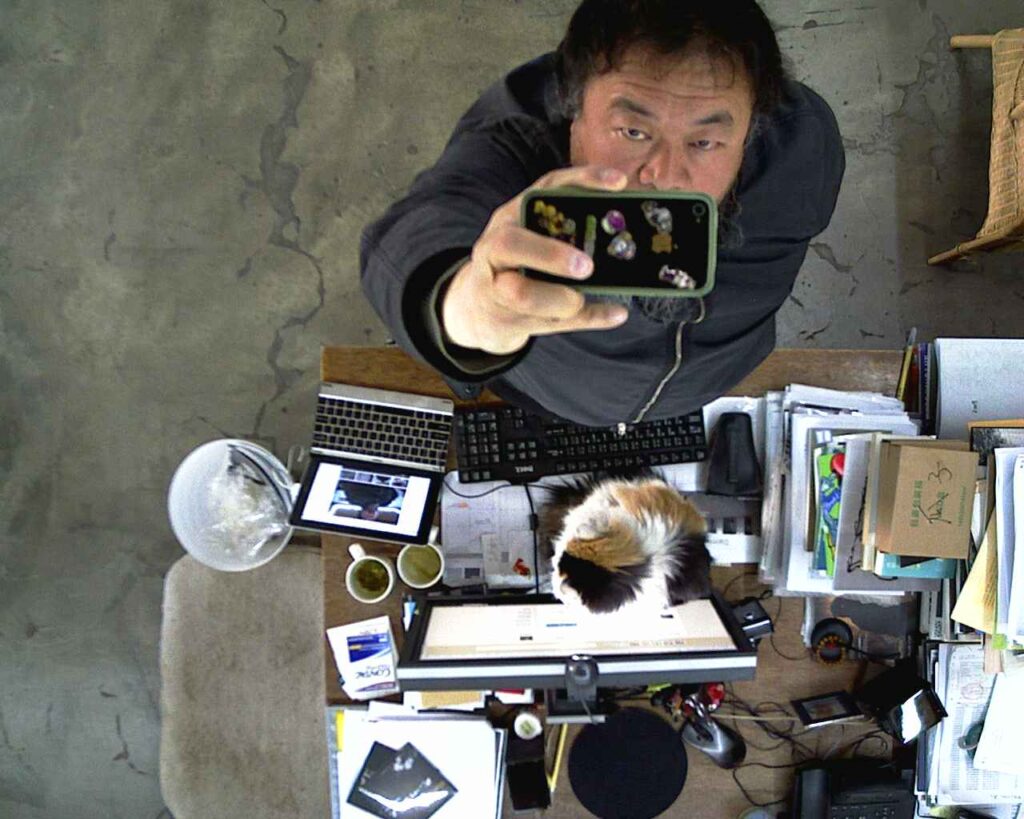

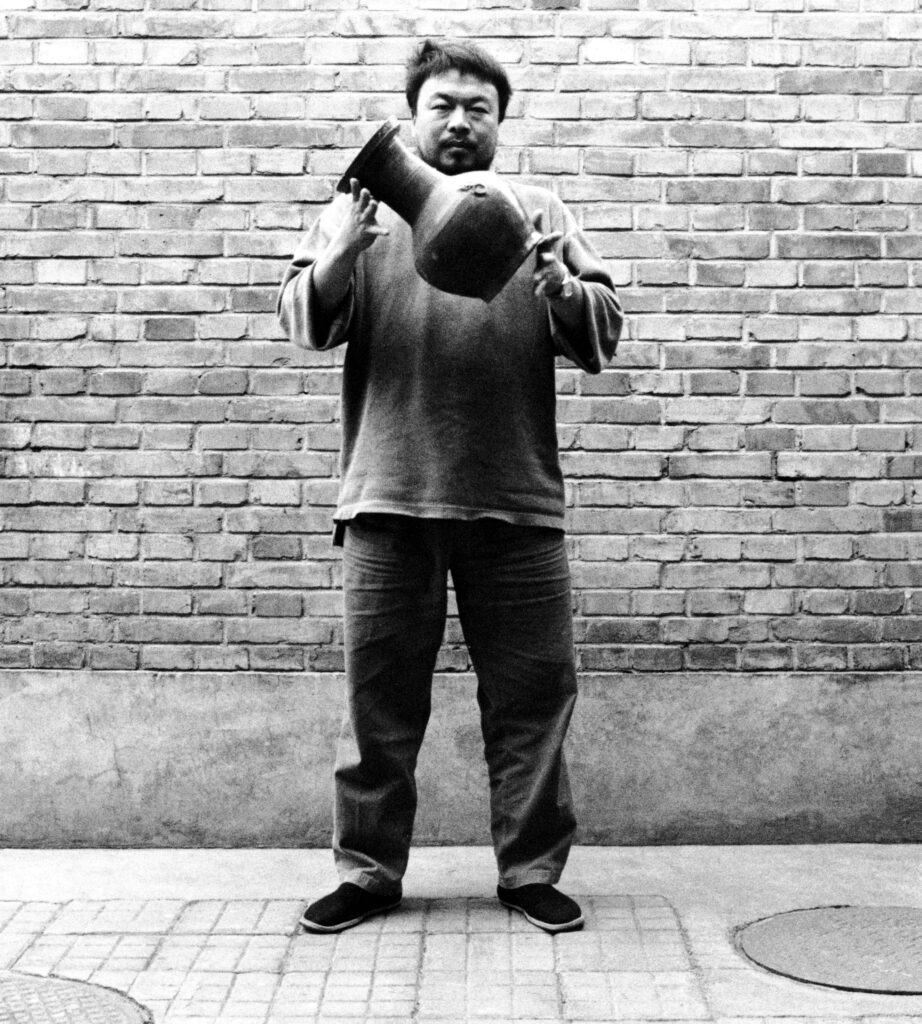

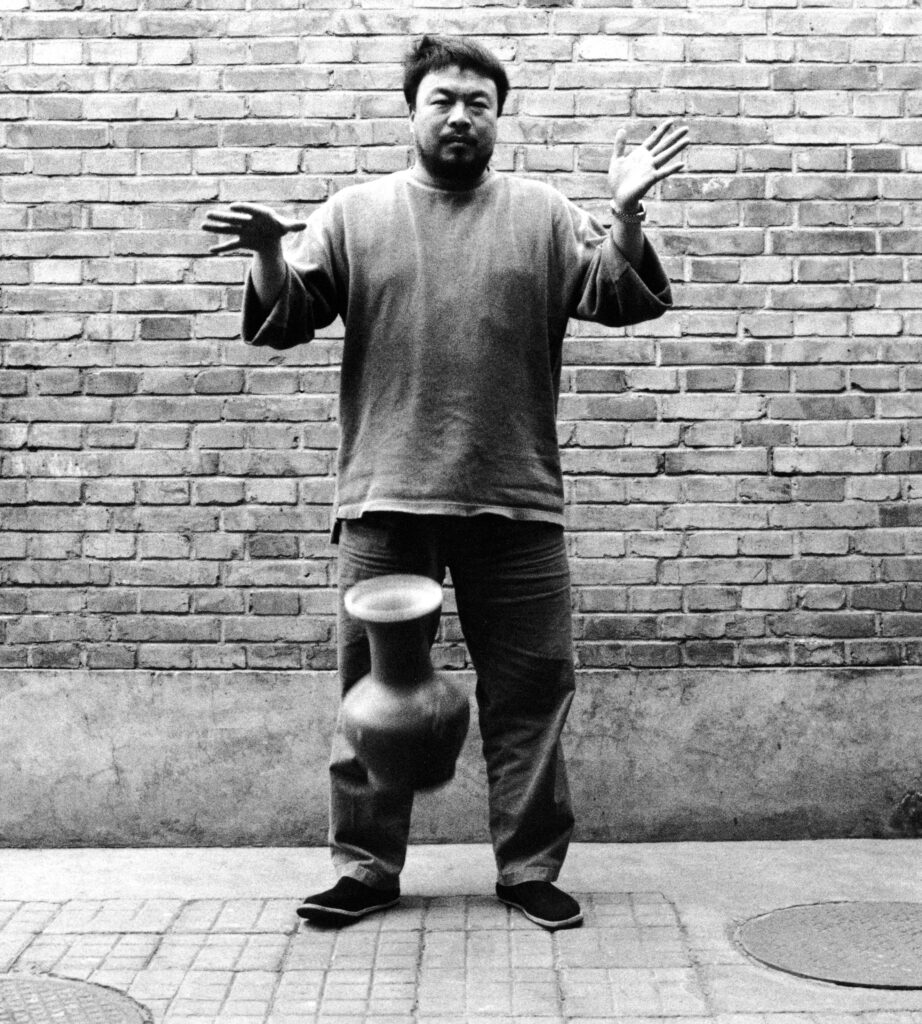

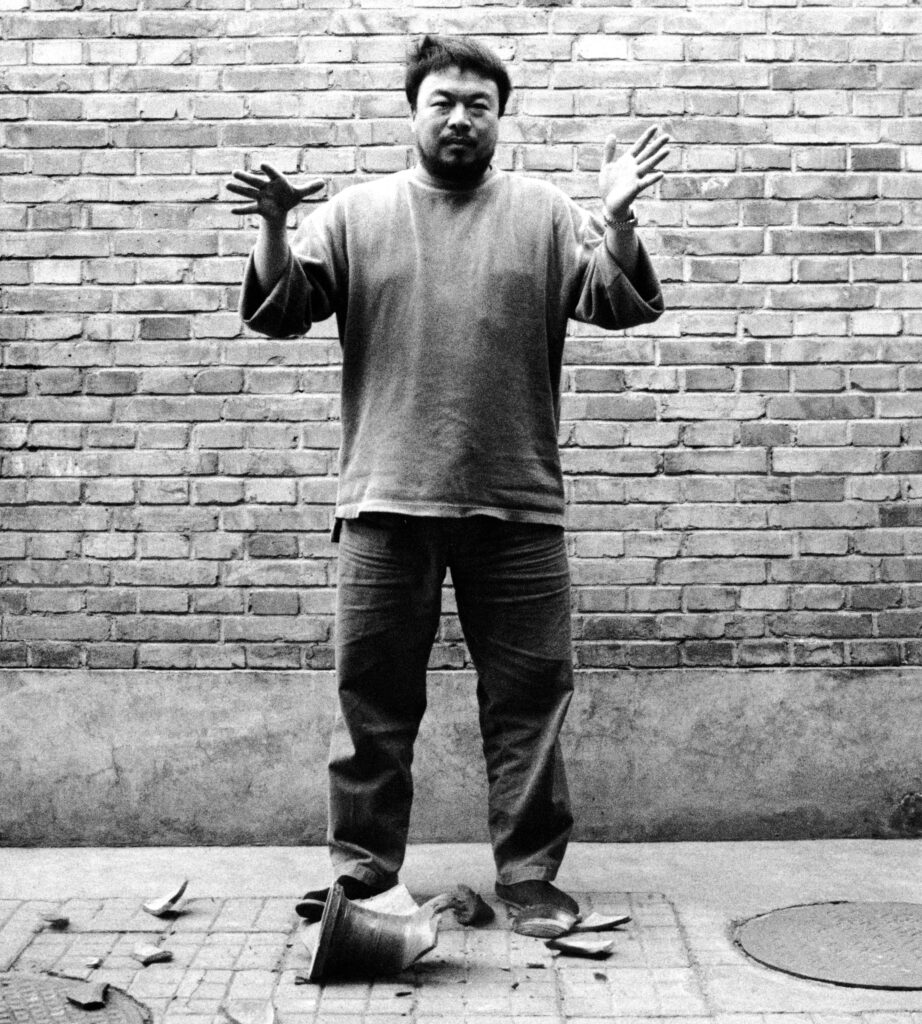

- WEIWEI CAM, 2012 DROPPING A HAN DYNASTY URN, 1995 (1)(2)(3)

- GLASS HELMET, 2022

- MARBLE TAKEOUT BOX, 2015

- AI WEIWEI PORTRAITS Photographs by Luba Kozorezova

All artwork images courtesy of the artist