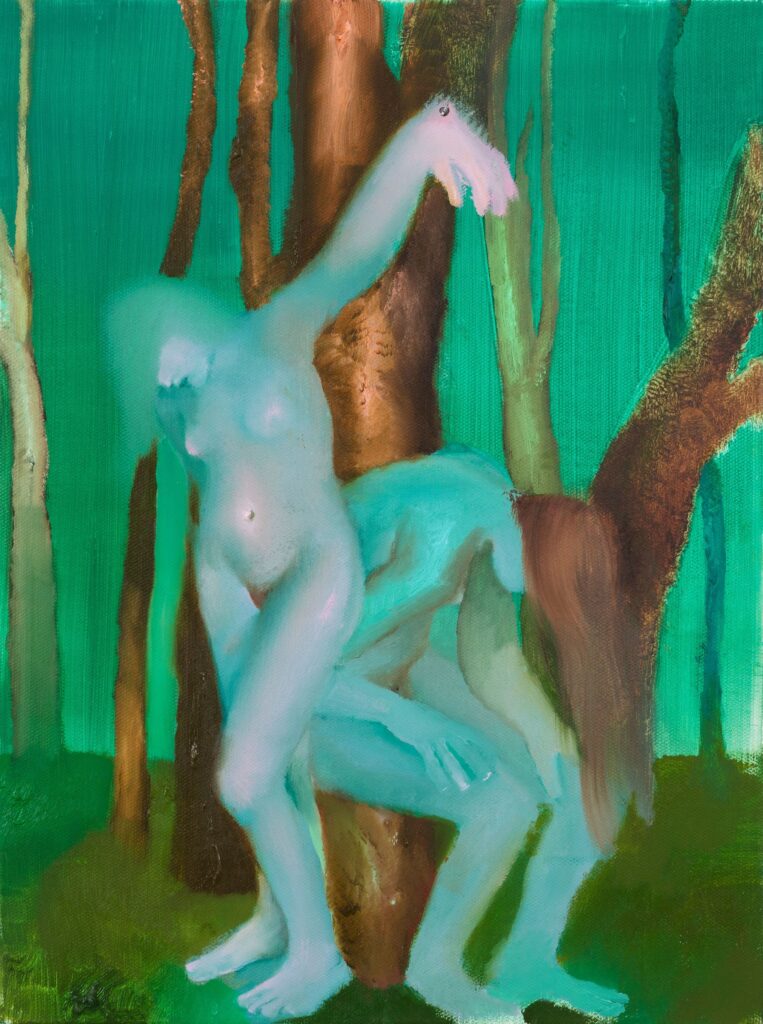

Elizabeth Glaessner, Ocean Halo, 2021

Therapeutic gateways to an inner world, Elizabeth Glaessner uncovers the realms of the psyche conjuring up a surreal universe in a constant state of metamorphosis.

Elizabeth Glaessner (born 1984 in Palo Alto, California) is an American painter and artist whose work express meanings beyond the figures she paints. Inspired by heroes of symbolism such as Edvard Munch, Odilon Redon, personal memories and art history, Glaessner places the visible at the service of the subconscious and re-contextualise mythological elements in her dream-like paintings. With her distinct use of colour, such as the recurrent visceral acid green as well as her technique of dispersing pure pigments with acrylics, oil and water, Glaessner creates visually striking works that tap into our primordial unconscious, opening a world where surroundings and people are intuitively blurred. There is a sense of fluidity and openness in Glaessner’s work, inspired from her childhood memories and an understanding that the world as it is today cannot be limited by binary thinking. Glaessner thus pushes the conventional societal boundaries and moral codes, and uncovers the realms of her psyche conjuring up a surreal universe in a constant state of metamorphosis.

Therapeutic gateways to an inner world, Glaessner’s paintings are indirectly a reflection of our time and a window to possible futures.

When did you start painting? Were there family influences at all?

My mom studied and taught art, so I started drawing and painting at a young age. Her dad was an art lover as was my grandmother on my dad’s side. Her twin brother Friedreich was a textile designer and my great aunt Mitzi was a watercolor painter.

Elizabeth Glaessner, War in the Middle Ages, 2022

You are originally from Houston, Texas but moved to New York. How have those two distinct landscapes influenced your practice?

I grew up in Houston, my parents moved there from California when I was 3, and I moved to New York in 2007. Houston is a large sprawling city with lots of space. It’s hot and humid and the vegetation and landscape is pretty swampy. It also flooded a lot so it’s a pretty wet climate on the east side of Texas. Lots of frogs and lizards. I’m not sure how much has changed over the years with all the new development. New York is much more fast-paced. Everything is compact and efficient. I love being able to commute without a car and my community is very important here. I’ve gained so much from being able to visit friends’ studios and having access to so many galleries and museums. But it’s very different working here than in a place like Houston and it’s getting more difficult with out of control rent and limited space. There’s always a tradeoff.

Elizabeth Glaessner, Earth Bound, 2022

There is always a sense of fluidity and openness in your work, on different levels, pushing away moral codes and societal limitations. Bodies and genders are interchanged and intertwined. Why those particular thematics?

I grew up in a pretty chaotic environment. When my parents divorced, my mom met an ex nun who moved in with her. The nun was obviously very religious and used fear tactics and violence to maintain power and control. We grew up in two very different realities. My dad’s parents were Jewish and escaped the Holocaust from Vienna so he grew up agnostic and didn’t impose religion on us. Eventually the nun left, I remember feeling overwhelmed with a sense of freedom. So I learned pretty early on the destructive effects of imposed morality, fear and repression and also became aware of our incredible ability to adapt and change.

“I also quickly became aware that we’re quite complicated and can’t thrive in a world limited by binary thinking.”

Elizabeth Glaessner,

Professional Mourners, 2020

Your work feels like an invite into your psyche and dystopian spaces in which the subconscious and conscious coexist together. Do you see your practice as a therapeutic tool and thus liberatory?

Yes, initially painting was a way for me to escape but also try and understand a surreal and oppressive childhood full of contradiction. I started seeing a therapist at a young age but couldn’t talk about anything.

“Drawing and painting was a tool to deal with experiences in a non-literal way that I wasn’t ready to communicate verbally.”

It’s a survival tool for many people. I’m lucky that I had that.

Elizabeth Glaessner, Misfortunes of the City, 2022

You have cited Edvard Munch, Odilon Redon as references. Who/What else inspired your style?

The first works of art that I spent time with as a kid in the museum of fine arts in Houston were Bougereau’s the elder sister (but just for the feet), Derain’s landscapes with red trees and Turrell’s tunnel. These aren’t artists that I look at now but I think the effect that they had on me at a time when I was forming memories is relevant to subconscious decision making in painting now. I have looked at and continue to look at so much art throughout history – it plays a large role in how I conceive of my paintings so it’s very difficult to just name a few. I look at different artists for different reasons. For example, Cranach the Elder and Carroll Dunham because of how far they are able to take one idea or theme and stretch it with subtle formal variations. Or someone like Chris Ofili or Francesco Clemente for color or feeling, Birgit Jurgenssen for the body and so on.

Elizabeth Glaessner, Escapism, 2022

Some of your favourite readings? What is something/someone you have recently discovered and has marked you?

I’m currently reading Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro. I think he’s a brilliant writer. I also loved Never Let me Go. Haruki Murakami is one of my favorites. I’ve recently been thinking about Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, especially “uses of the erotic: the erotic as power” and how she writes about language in “Poetry is not a Luxury”. And my friend Aisling Hamrogue recently suggested I read a chapter in A Thousand Plateaus by Deleuze and Guattari called “One or several Wolves” discussing the body without organs which made an impression.

The colours used in your paintings offer such vibrant hues. Where does this palette come from?

It’s incredible how personal and associative color is. I have visceral reactions to certain color combinations. It’s often the thing that causes me to repaint a painting – if the color isn’t working with the content, I’ll start over with a different palette. Usually the under color shifts the tone of whatever is on top which can lead to unexpected combinations. There’s an element of intuition but I also think about symbolic associations of color – both my own which have been developed through repetition as well as learned associations.

Elizabeth Glaessner, Charley Horse, 2022

Some colours are more recurring than others, such as acid green. There is something really appealing to it but it also feels like a warning. Why that green in particular?

I’ve been drawn to that green since I was a kid. I’m sure it comes from many places. Houston is a swampy green city and I was always outside. I was very close with my grandmother who introduced me to painters such as Klimt and Kirchner who also use that green. It’s a color that I feel comfortable with.

“That acidic quality oozes an uneasiness which I think is reflective of what it feels like to be alive.”

Elizabeth Glaessner, Heat Map, 2022

Which mediums other than painting would you like to explore with?

There is an endless amount of learning I still have to do within painting. I’ve done silk painting – which is something I’d like to do again at some point. I’d also like to explore paper making, priming my surfaces in different ways, experimenting with different mediums when I’m pouring paint. I’d like to do some monotypes in a print studio and try different printmaking techniques. I’d love to play around with clay more but painting is keeping me pretty occupied at the moment.

Elizabeth Glaessner, Sphinx and Friends, 2022

Could you tell us about the process you go through when you create?

I usually start with several works on paper that are done pretty intuitively. Some drawing, some ink and gouache. First I pour and then use the color fields to find forms which I meld with preconceived ideas so there’s a balance of control and freedom. I look at these works on paper as I’m making paintings on canvas on linen, whether it’s the color and theme, or just the composition or energy. The surface of the larger paintings is often pretty built up because I change so much as I’m working. Sometimes the composition will work on a smaller scale but doesn’t feel right when I’m working large. I usually get to a point about halfway through where I feel like I’ve completely lost the painting and then have to make some big move to totally change it and dig my way out. But I’ve learned that that is just part of how it’s made so I trust it.

What are you working on at the moment?

I just finished my solo show “Dead Leg” which opens September 3rd at Perrotin in Paris. I had a pretty busy year so I’m looking forward to traveling a bit, taking some time to set up my studio again, finishing some books I started, doing some color exercises and starting a new series of works on paper.

The theme of this issue is IN OUR WORLD. Are your paintings a reflection of our time or are they a window to the future you envision?

I think they’re both.

“Definitely a reflection of our time which wouldn’t exist without the past and which hints at possible futures.”

Credits

Artworks · Courtesy of Elizabeth Glaessner and Perrotin