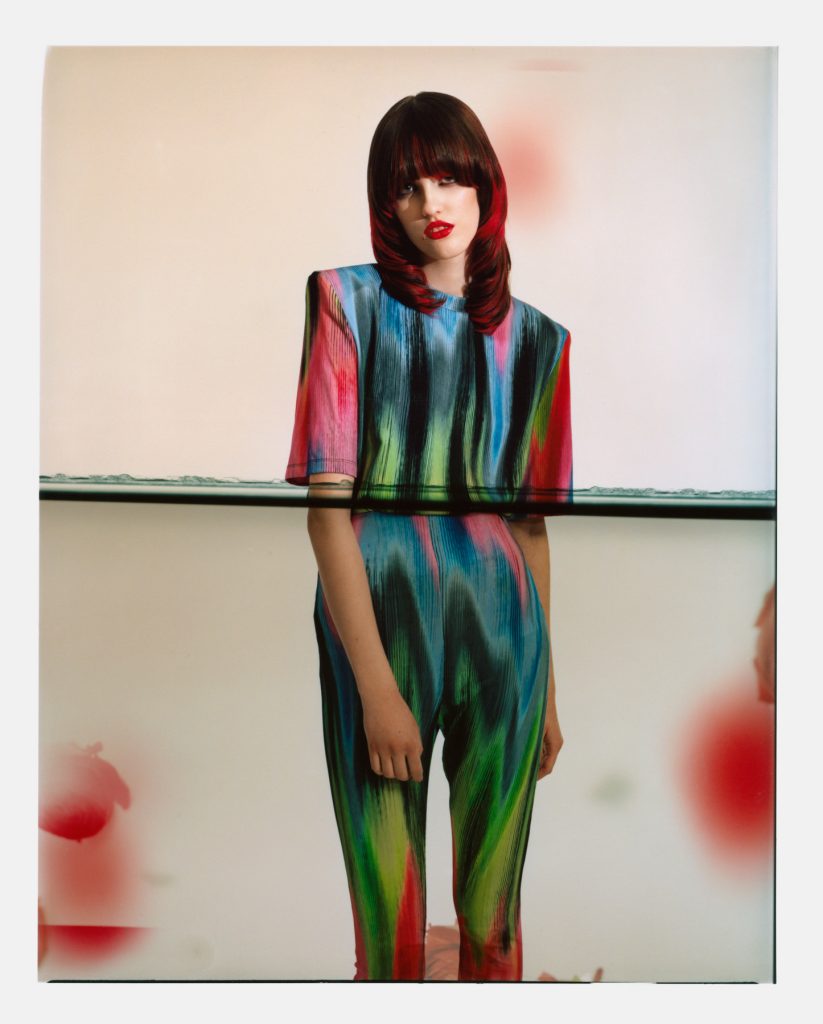

Credits

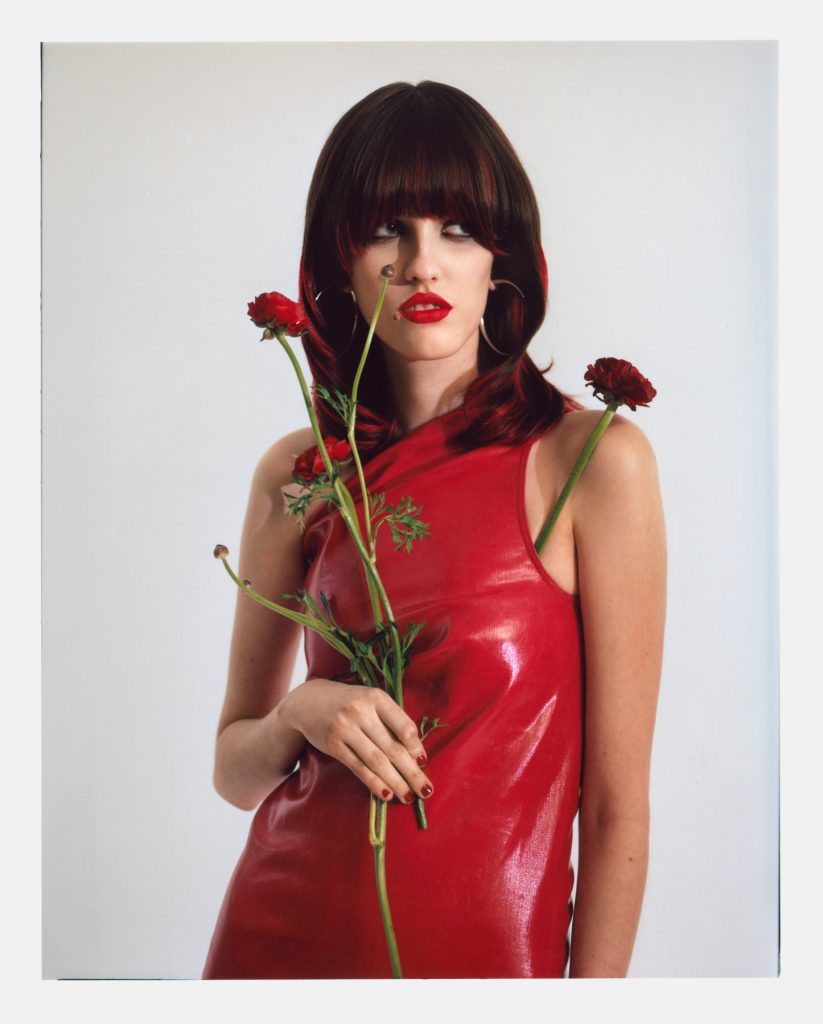

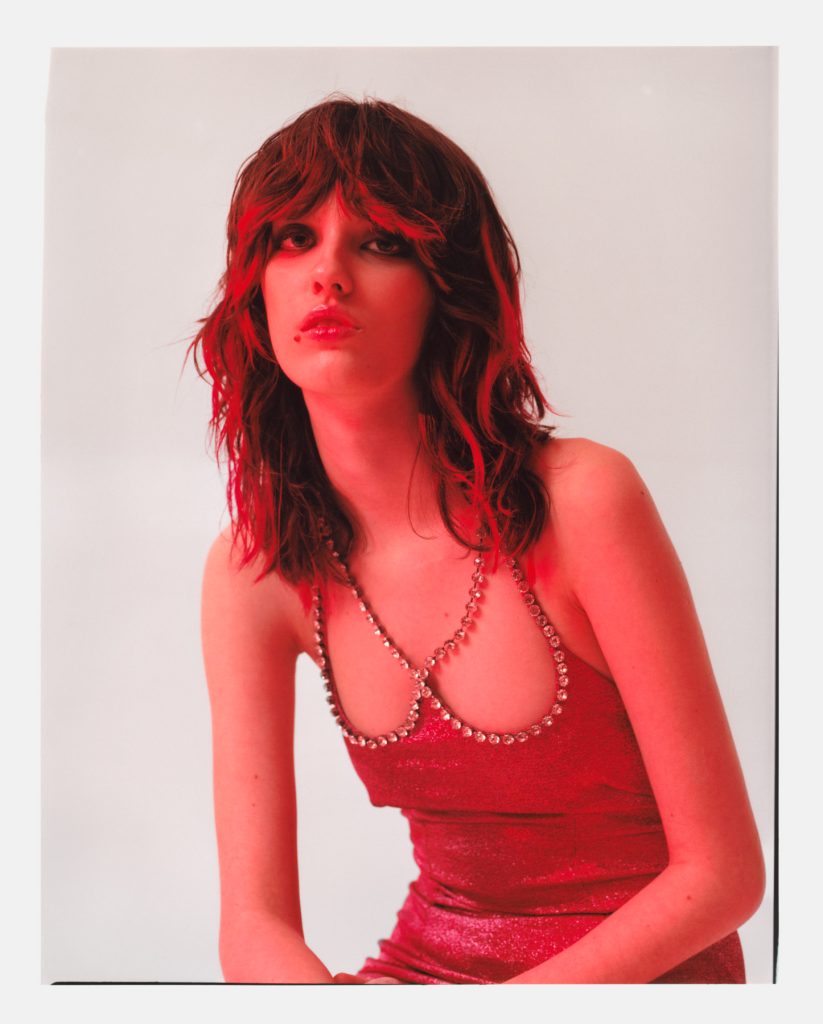

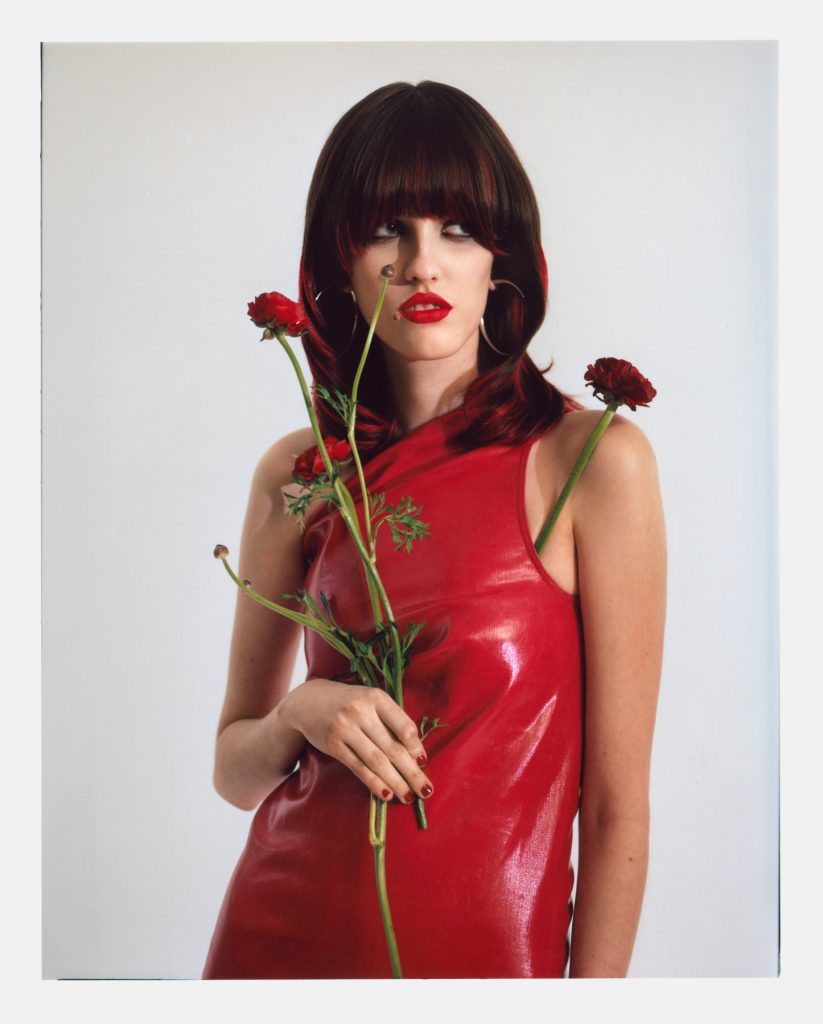

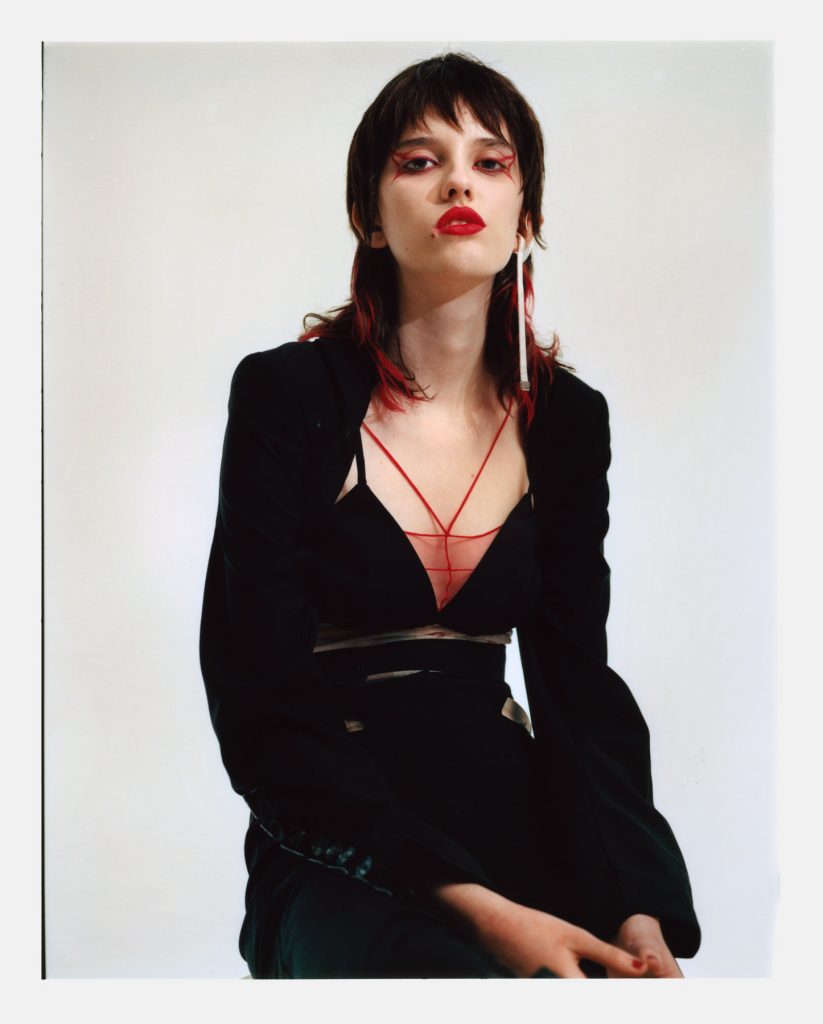

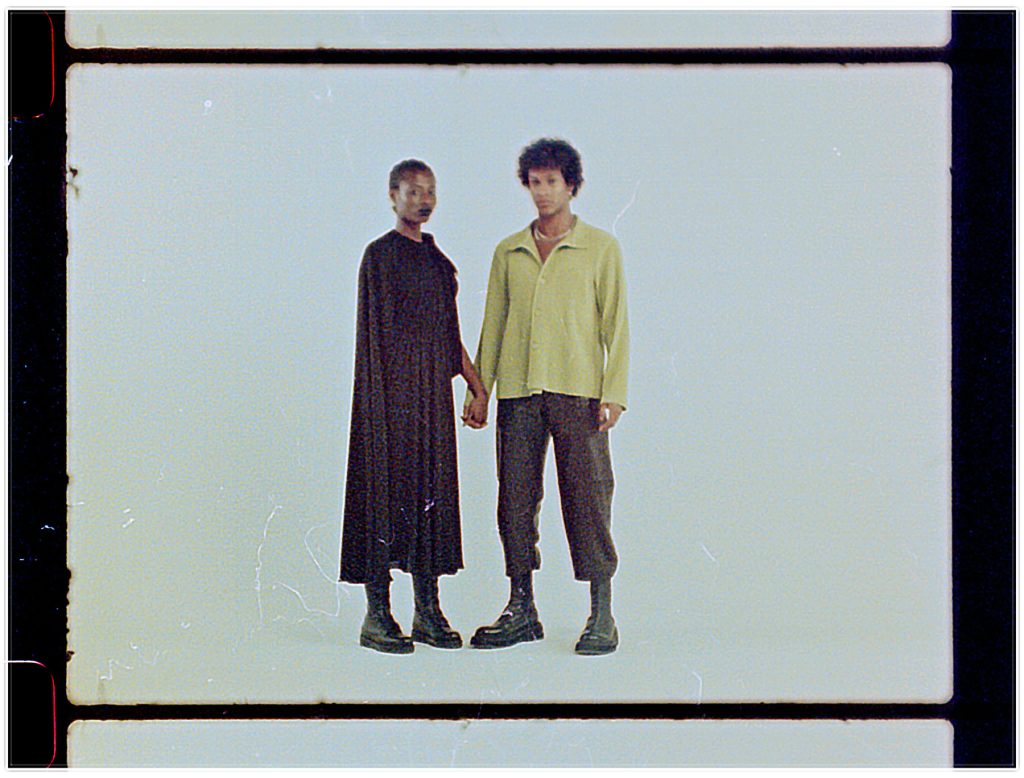

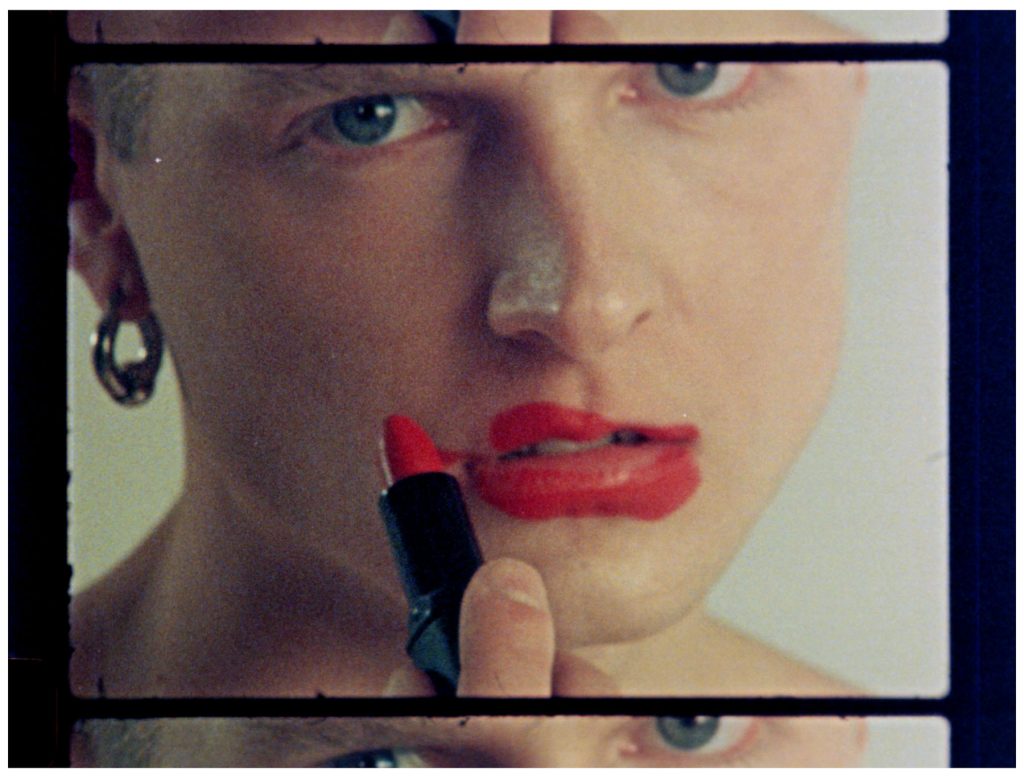

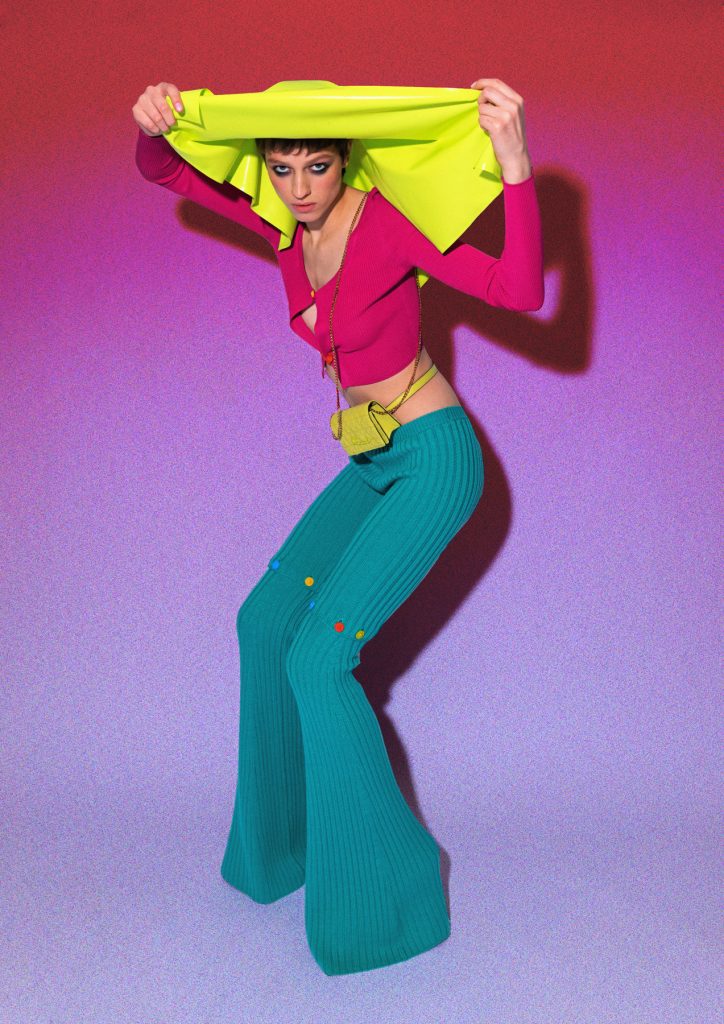

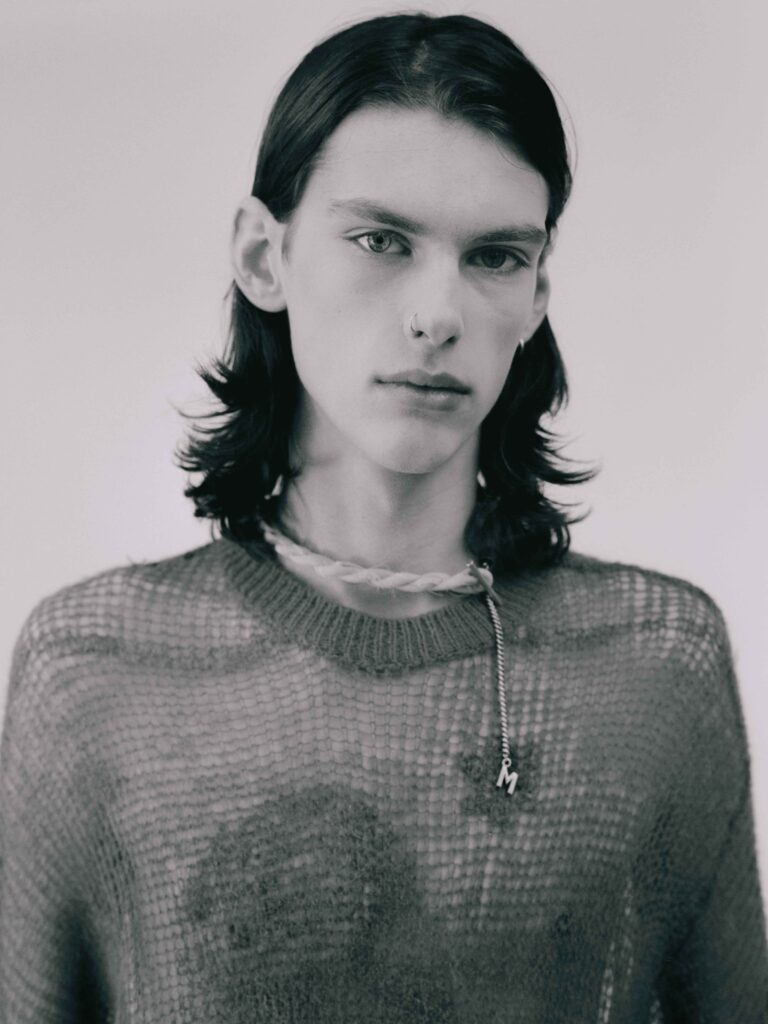

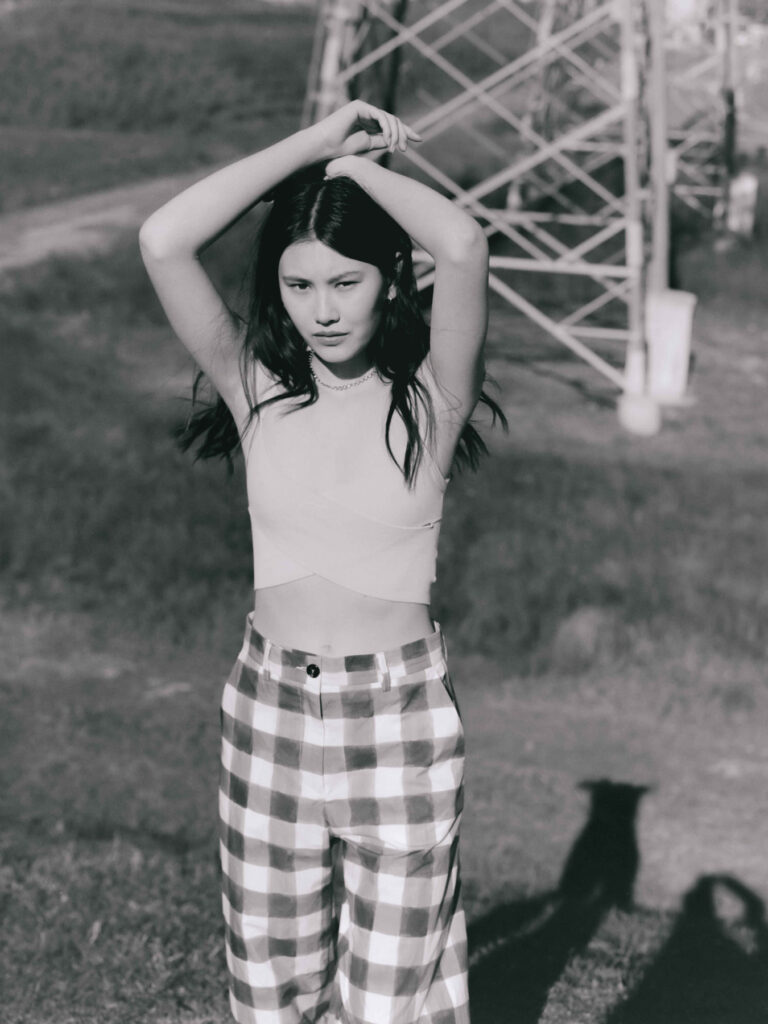

Model · STAN at FORD MODELS PARIS

Photography · NINA RAASCH

Fashion · FABIANA VARDARO at COLLECTIVE INTEREST

Casting · ELI SCHERER

Makeup · SABINA PINSONE

Hair · DIEGO FRAILE

Fashion Assistant · FILOMENA IANNICIELLO

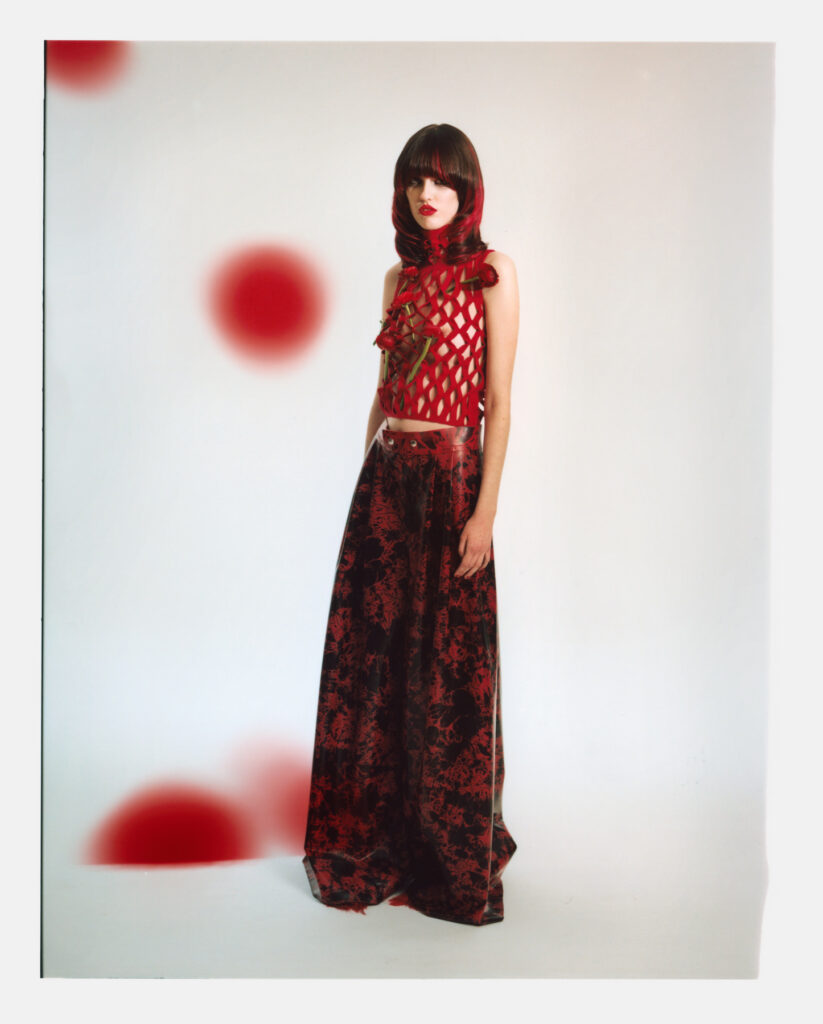

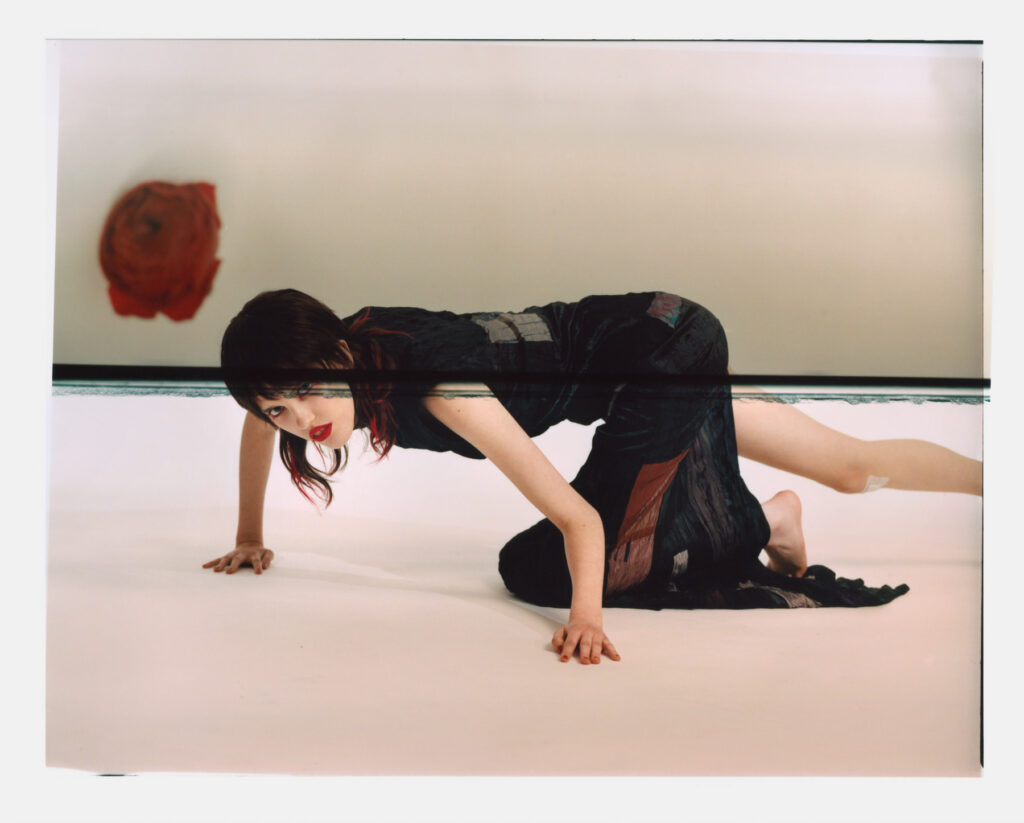

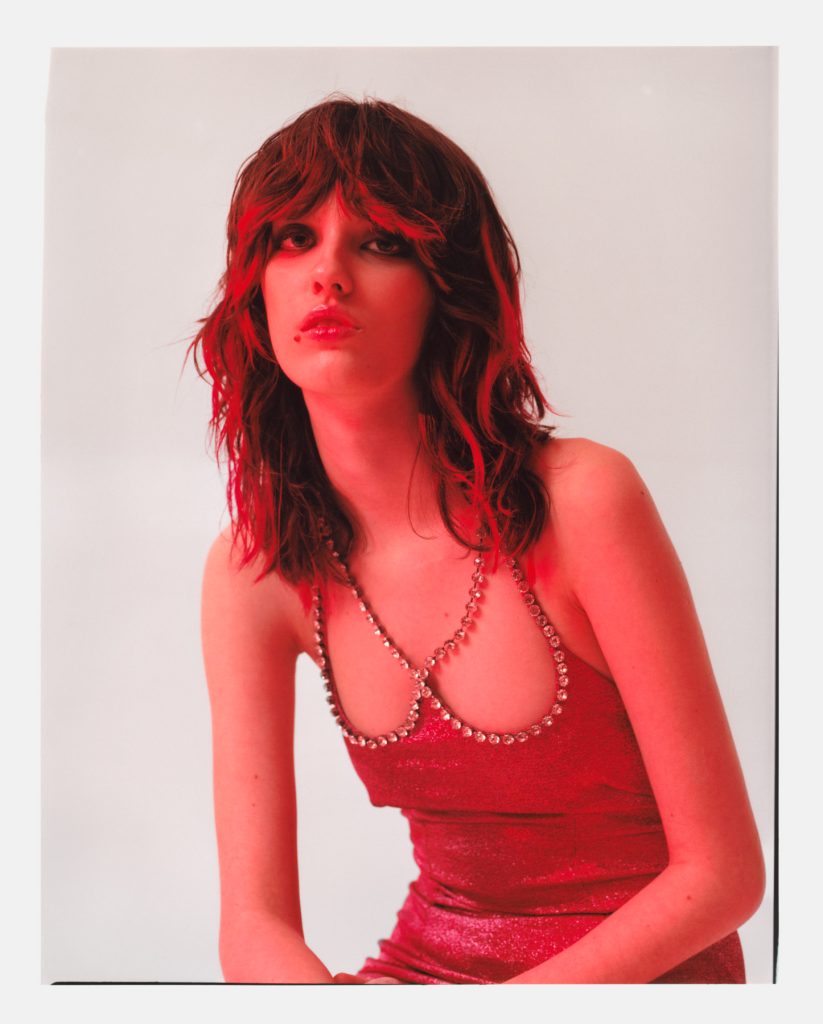

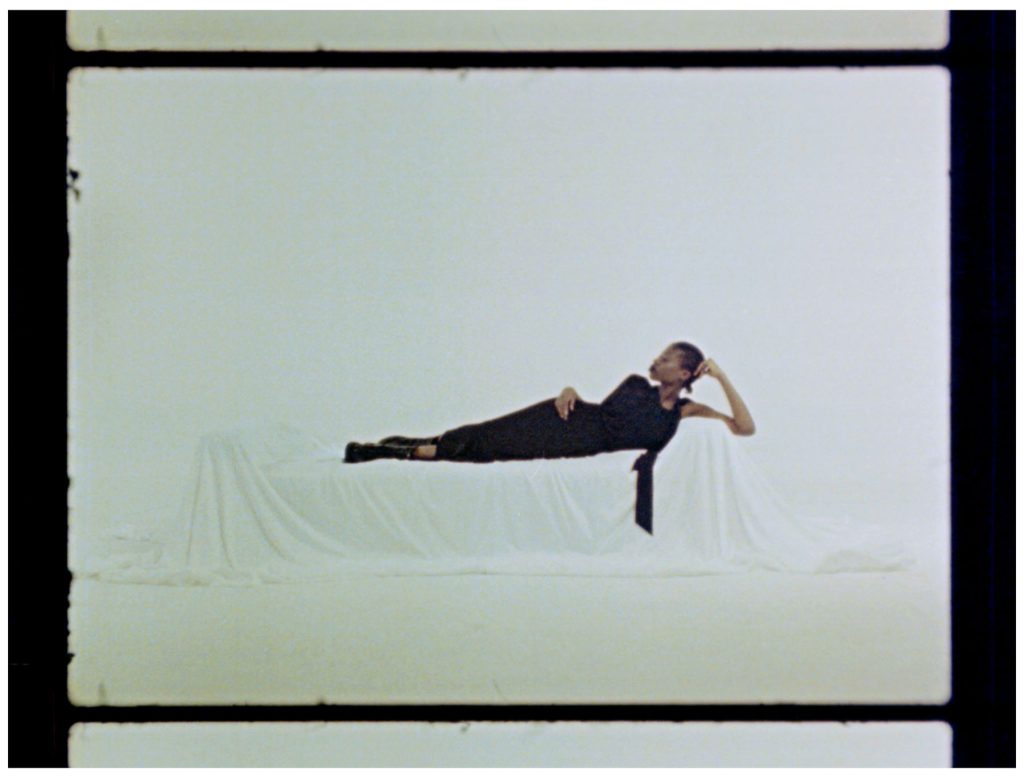

Credits

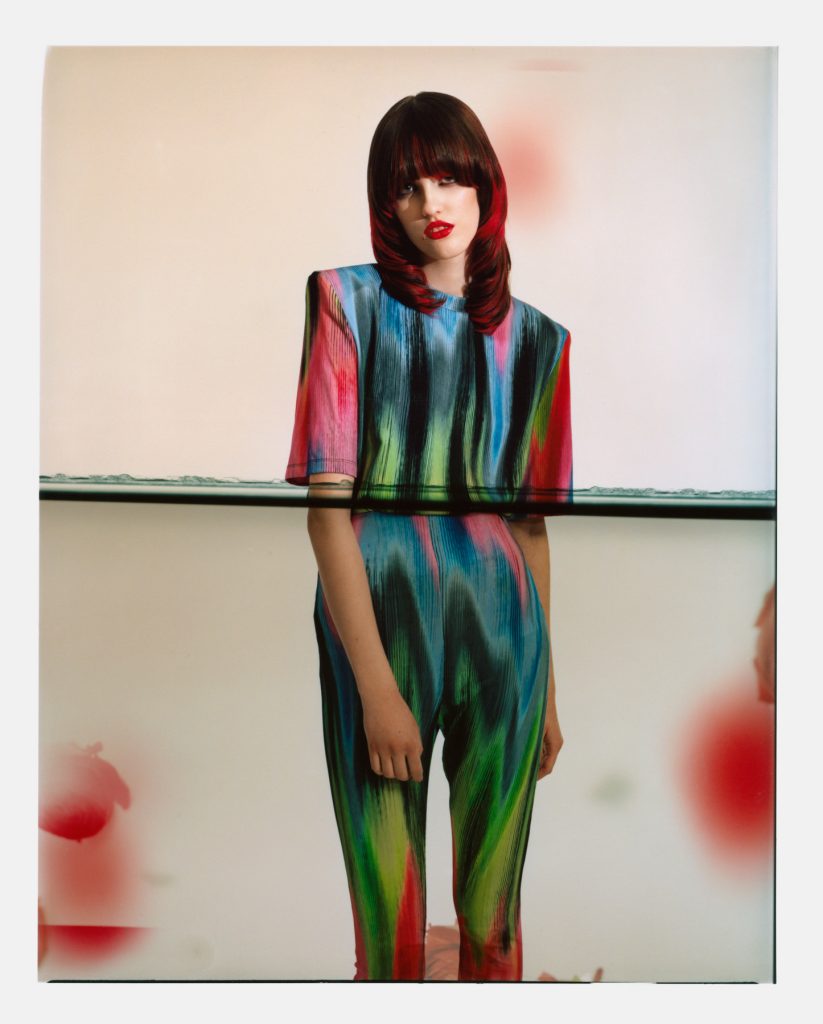

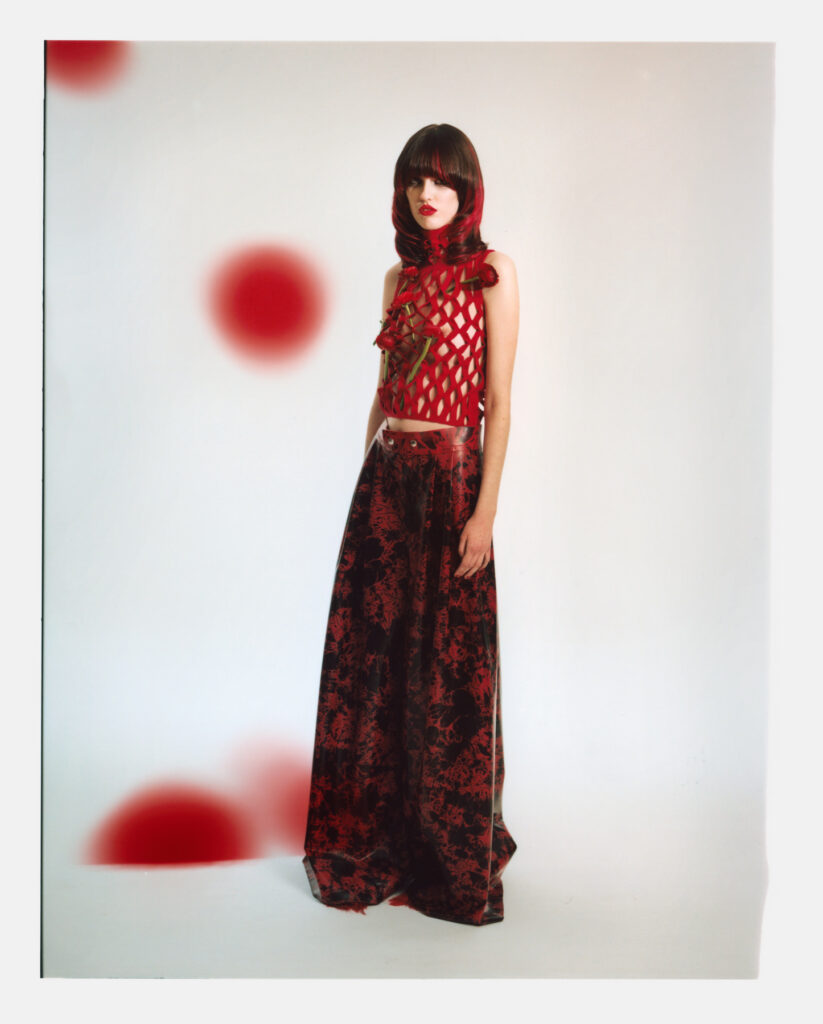

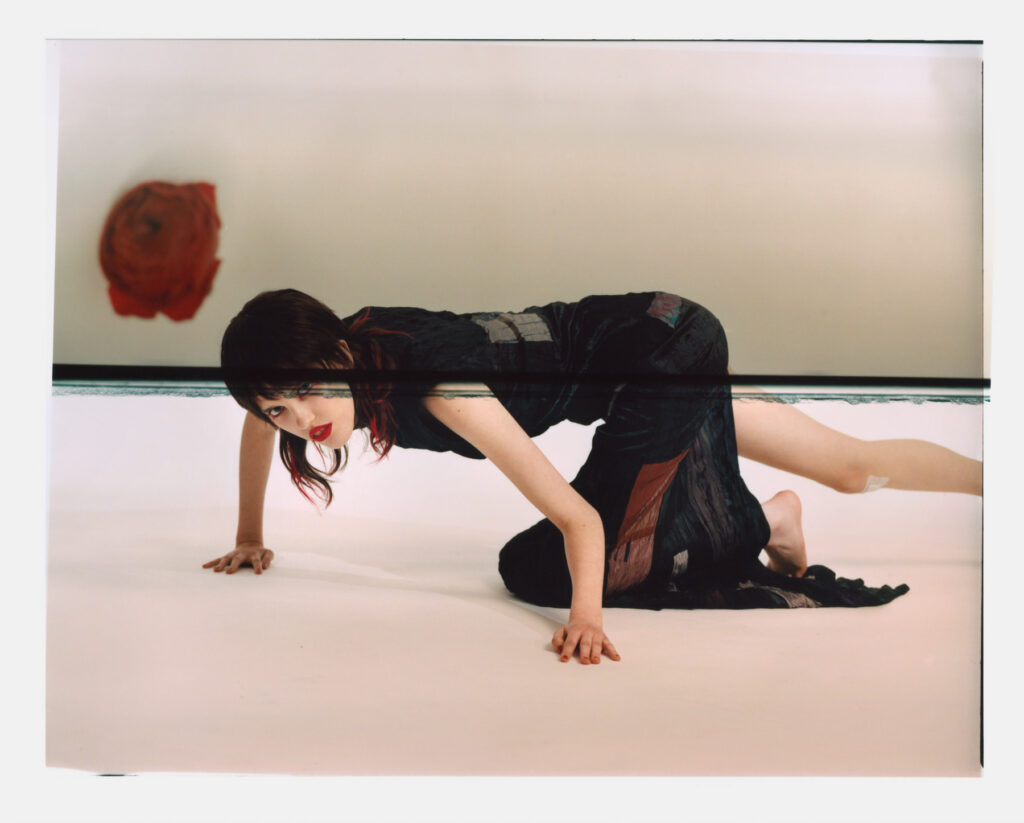

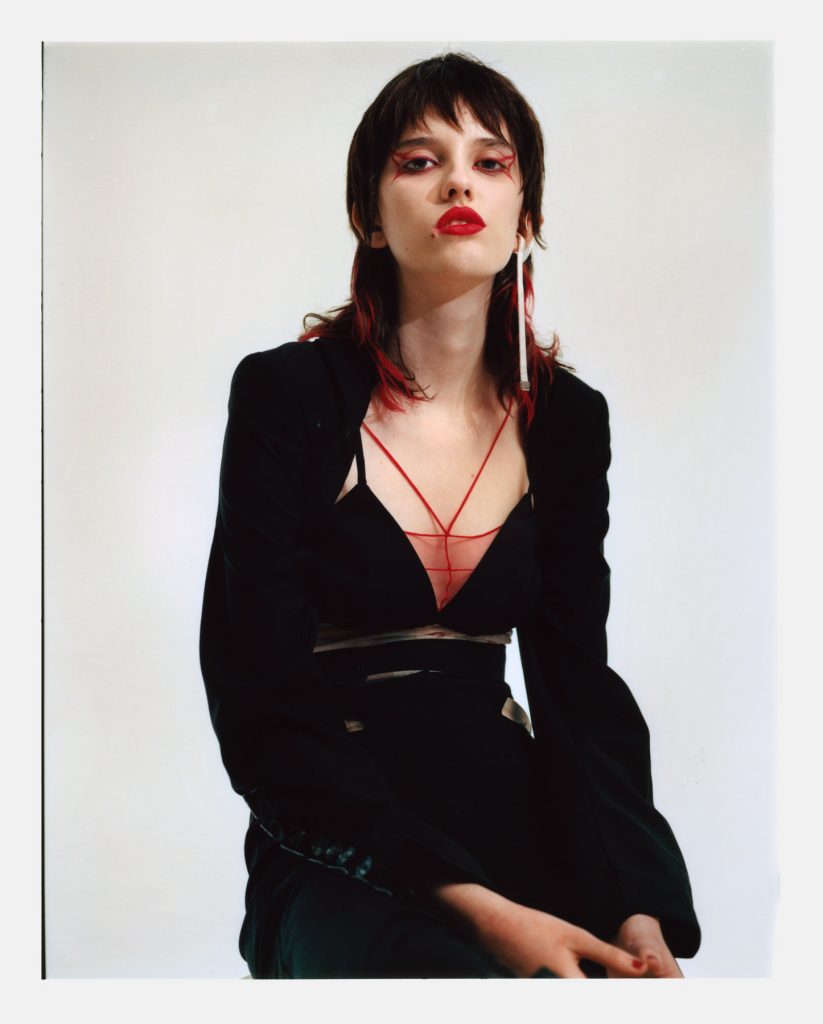

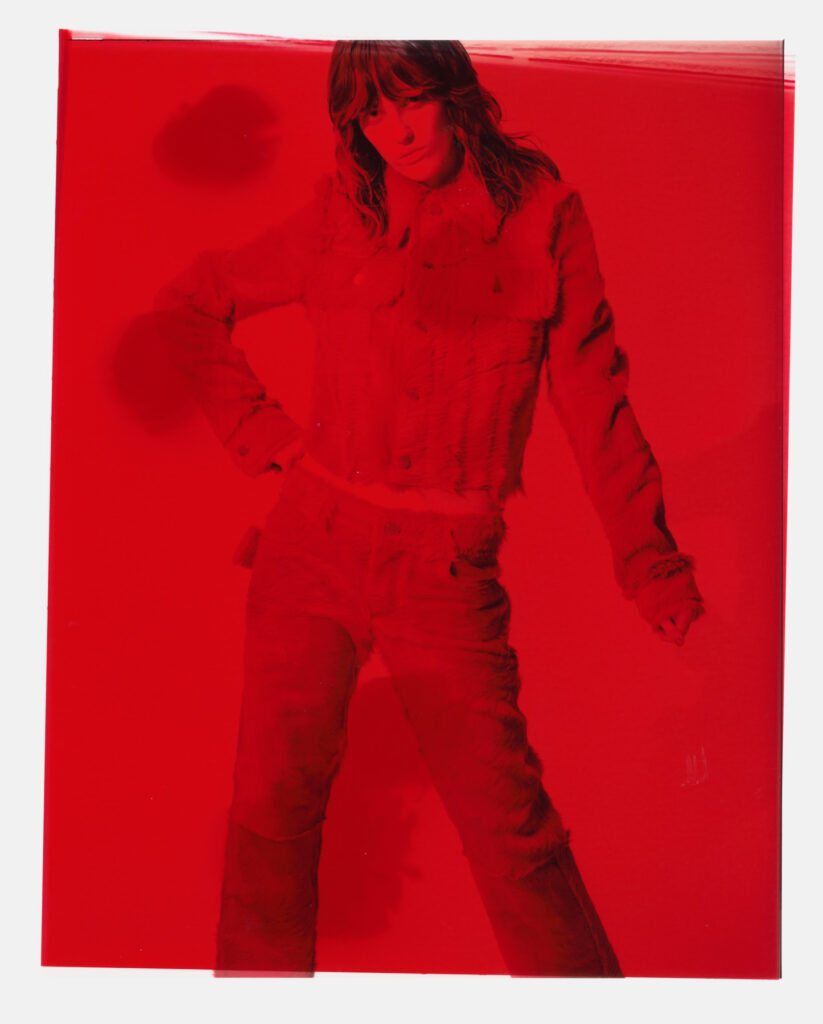

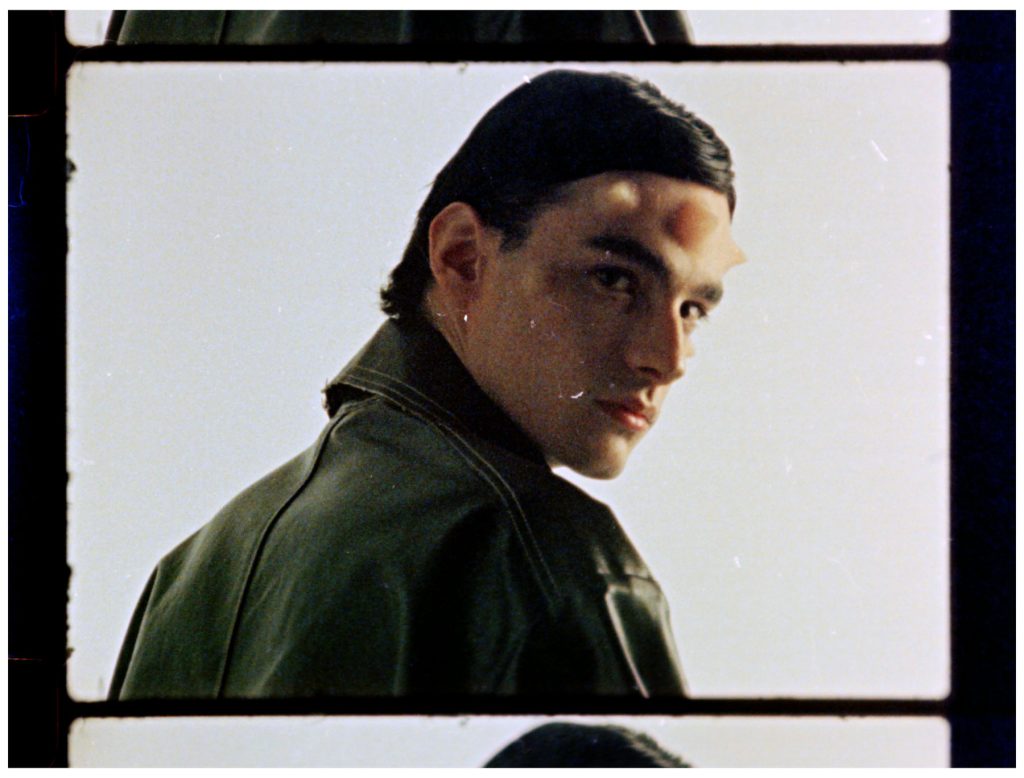

Model · STAN at FORD MODELS PARIS

Photography · NINA RAASCH

Fashion · FABIANA VARDARO at COLLECTIVE INTEREST

Casting · ELI SCHERER

Makeup · SABINA PINSONE

Hair · DIEGO FRAILE

Fashion Assistant · FILOMENA IANNICIELLO

Nicholas Préaud’s fondness for furniture and product design brings him satisfaction on different scales in different timelines. The liberty and authority these designs lend him feed his creativity to break through the boundaries between what exists in the digital and physical world. In fact, some of his projects touch upon abstraction, works that only serve the digital altar. As he investigates, researches, and develops plans and methods to bring these digital works to life – together with Kei Atsumi – Préaud finds himself invested and knee-deep in his design and work principles, an indication of a positive intensification in his design, architecture, and construction research and development.

NR: A focus on design, architecture, and construction research and development: what made you pursue a creative studio on these themes? Where did this strong affinity for these themes come from?

NP: I am a Paris-based architect and designer. I pursued architecture studies in Paris and subsequently worked in several architecture firms such as DGT Architects, Lina Ghotmeh Architecture, Nicolas Laisné Architectes, and more recently Sou Fujimoto Architects in Paris. My background is purely architectural and bridges several practices such as smaller-scale furniture or product design, and construction R&D. My practice spans today from furniture design, interior design, architecture, and R&D (all designed to be built and used in real life) to more abstract and digital works of design meant to exist only digitally. Some projects such as Casa Atibaia are ways of bridging the gap between the digital and the physical world. Initiated as a digital architectural project, we are now working on bringing it to life in the years to come.

Furniture and product design has always been a go-to theme for me to work on as it brings satisfaction on a different scale as well as a different timeline. As architects, we often get lost in never-ending processes due to political or financial parameters that are out of our control. Furniture design gives me more liberty and control over the creative process, and ultimately the finished product. Although my practice aims at a certain form of humility in the creative process, it is also progress-driven, which naturally leads me to invest time and resources in research and development. In the past two years, together with my friend and partner in this adventure, Kei Atsumi, I have designed and put together a manufacturing process for a joining system of architectural elements. We subsequently patented the design and process to bring it to life in the years to come. The joint system aims to allow for any architectural elements such as beams, pillars, or panels to be assembled to one another without any tools or a particular skill, a seemingly interesting subject for disaster relief construction for instance.

How essential is construction research and development in creating design and architecture? Do they go hand-in-hand?

They most often don’t go hand in hand at all in my experience working in Parisian firms. In France at least, these practices are very compartmentalized. Architects work on design and engineers work on R&D. I would say that focusing on R&D applied to architecture makes sense when you want to go beyond the existing techniques and processes which exist and have been normalized. It isn’t essential, but it contributes to broader progress and helps create new techniques and expertise ultimately making the construction process more efficient and sustainable.

I want to learn more about your design process. Do you start with a single concept then go from there, or an already-envisioned product? Is it challenging to lay out the design plans? How many revisions do you go through?

I usually neither iterate so much during the design process nor do I start with an already envisioned product or project. A concept often emerges early on because it makes sense, and is then pushed further until completion.

“I believe there are as many valid concepts as there are approaches to the same project.”

It’s just a matter of it making sense to the final users of the space or product, and of course to you the designer. Depending on the scale and complexity of the project, iterations and revisions are nevertheless bound to happen. This is where engineering and construction knowledge proves useful in the design process. Accurate engineering can be taken into consideration early on in the creative process to avoid painful iterations. My architectural work has been and is for now on a scale not exceeding that of a private home. In this sense, once the wants and needs of the client and the natural context of the construction have been well understood, the design plans follow easily.

Do you prioritize functionality over design in your products? Also, would you say you practice the less is more philosophy?

To a certain extent, I would say I do try to practice the less is more philosophy. I truly believe excellent functionality can be achieved without compromising on design. True utility often suffices to bring beauty out of any given design. In my work, I enjoy emphasizing the simple technicalities of how a given object, space, or building is assembled by revealing the sheer power of the forces at play. Functionality in some cases can also become overly complicated and fussy. Design that doesn’t seek to fulfill a specific given functionality sometimes brings out so much more, as theorized by James J. Gibson with the concept of affordance and perceived action possibilities of an object.

Noting the titles of your design products, there is a touch of East Asian culture in them. What lifestyle or philosophy do you practice that roots from East Asia? Is there a difference between the way East-Asian culture works and that of European and Western one?

My work is impregnated with many references to East Asian culture, specifically Japanese culture. Having been very passionate about the Japanese culture and architecture in my entire life, and having worked at internationally renowned studios led by Japanese architects such as Tsuyoshi Tane or Sou Fujimoto, I have learned a lot about, and continue to seek to learn about, how architectural design can entertain an essential relationship with its foundational natural counterpart. A simple relationship between the artifact and the untouched, and layouts intentionally designed to encompass empty space where anything can happen are essential to me, as opposed to Western architecture and its spaces impose a function on the user. The concept of ‘Ma’ in Japanese culture and architecture exactly points to this.

“The invisible aesthetic of Ma is portrayed by this energy filled with possibilities emerging from the design, an emptiness that reveals unforeseen functions.”

Let us talk about your architecture repertoire. There is a sense of calm in your designs, from the light hues of the interior to the arrangement of the fixtures and furniture.

How do you decide what color and style to use? Do you compromise with your clients’ briefs?

I tend to iterate much more on textures, colors, and furniture than actual sheer architectural geometry which comes more naturally to me. The sense of calm you are referring to probably comes from the essentialness of uncluttered spaces, once again not imposing function but revealing it. In terms of color and style, I would say I try to adapt as much as I can to the context of the design rather than imposing my own. I feel an architectural design is well rolled-out specifically when you cannot recognize its author through the style, but rather through the creative pro- cess which led to its materialization. In this sense, the creative process can lead you in so many different directions.

That is what is interesting to me; each design exists in its own context and with its own referential universe tied to it, not so much its author’s aesthetics.

“That is what is interesting to me; each design exists in its own context and with its own referential universe tied to it, not so much its author’s aesthetics.”

What has been your most challenging project so far? What and how did you learn from it? Also, how would you describe your work ethic through your projects? What architectural elements do you pay attention to?

My most challenging project has been and continues to be Casa Atibaia which I designed in collaboration with Char- lotte Taylor. This project encapsulates so much of what I try to push towards in my practice. Architecture that does not wish to disappear in its surroundings, nor shows off extravagantly either; architecture that exists through the multiplication of natural forces. Started in early 2020, the project was first rolled out as a way of putting forward ideas and our interpretation of Brazilian modernism. Having lived and studied architecture in Brazil, this project resonates so much with me. Phase one of this project which we rolled out in 2020 was met with great enthusiasm and gave us extra incentive to continue pushing for it to materialize. Phase two which will be released soon brings us even closer to this imagined dream-house and consists of a short film and VR experience allowing the viewer to immerse themselves completely in the design in a way the still shots didn’t let you. Phase three which we are very optimistic about will be rolled out in the coming years and will materialize through the construction of the house. We have been in discussion over the past year with clients who are also guiding us through the process.

A question on a title: is there a difference between an architectural designer and solely an architect or a designer?

There is no difference I know of or intended other than this title is the most broad-reaching one I could find on Instagram to define what I do, which is a broad scope going from object and furniture design, to architecture, to digital works, and research and development.

It seems that we have to look forward to your research and development content. What can we expect from you in the upcoming months?

Speaking of which, I have yet to update my website as I am waiting on legal deadlines to communicate more broadly on the R&D aspect of my practice. For the past two years, my partner in this adventure, Kei Atsumi, and I have been developing a joint system that allows anyone to assemble and disassemble architectural elements without the use of tools and without any particular skill set. This joint system is sturdy over time and can be manufactured for panel or framework structures. No tools and no skills prove useful for certain types of constructions including but not limited to emergency architecture and lower-scale wooden homes. Two years of research and development have led to the successful patenting of the system in Japan, which we are now working on marketing and developing more seriously. As this is a slow process, I do not have a date for release but we are working to get it manufactured and on the market as fast as possible.

Our issue touches on the concept of Celebration. Some people seem to only revere design and architecture for their face value. For you, why and what should celebrate (in) design and architecture? For instance, in Casa Atibaia, you seem to celebrate the force of nature. Does nature drive your philosophy in design?

As mentioned above, and also just now by you in the clearest way, my work explores the relationship each design entertains with its surroundings and founding natural elements. As our culture and humanity tend to distance themselves more and more from the most basic and essential connections we still have with the natural elements, I feel the urge to explore and question how this can still happen on a very basic level. I celebrate humility and simplicity in design, that which feels obvious, which looks like it should be rather than not. A lot actually looks like it should not.

“I celebrate the designs whose creative process and formal results are more relevant than their authors.”

Continuing the theme of celebrating nature, you also collaborated with Charlotte Taylor for Coral Arena. How did this collaboration unfold? How can your collaboration fuel the discussion on climate change?

Charlotte and I were approached by the team at Aorist, which is a next-generation cultural institution supporting a climate-forward NFT marketplace for artists creating at the edge of art and technology. Together with the team at Aorist and OMA New York which is one of, if not the, leading architectural firms in the world, we produced a film that portrays the life of a physical artwork that will be installed in the future as a part of the ReefLine masterplan—it is a digital twin to a sculpture that will live and grow over time, depicting the sculpture as a piece of resilient infrastructure. Proceeds from the sale of this release will be donated to The ReefLine, an artificial reef, marine habitat, and sculpture park in Miami Beach. This project was our first meaningful jump into the NFT format and made sense to us creatively and of course, because of the cause it is supporting. We hope the film is viewed and appreciated by many, and that it helped educate the public about what is unfolding and what has yet to unfold in the years to come on the Miami coastline.

Credits

Images · Nicholas Préaud

https://nicholaspreaud.com/

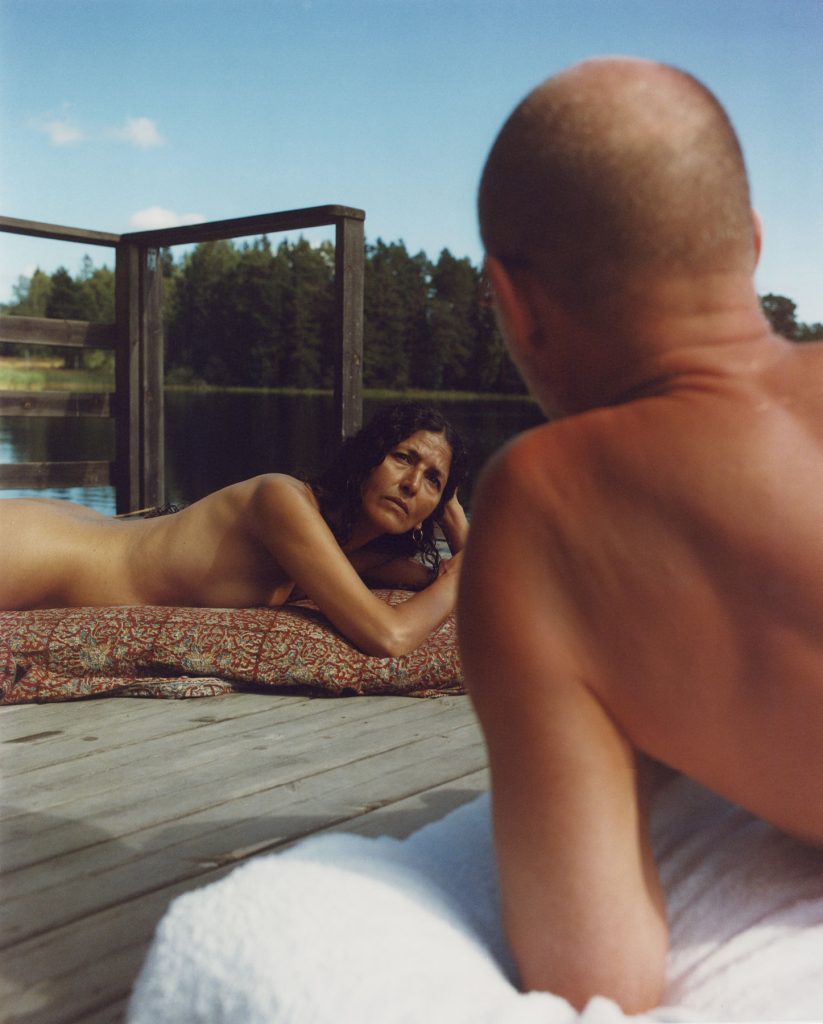

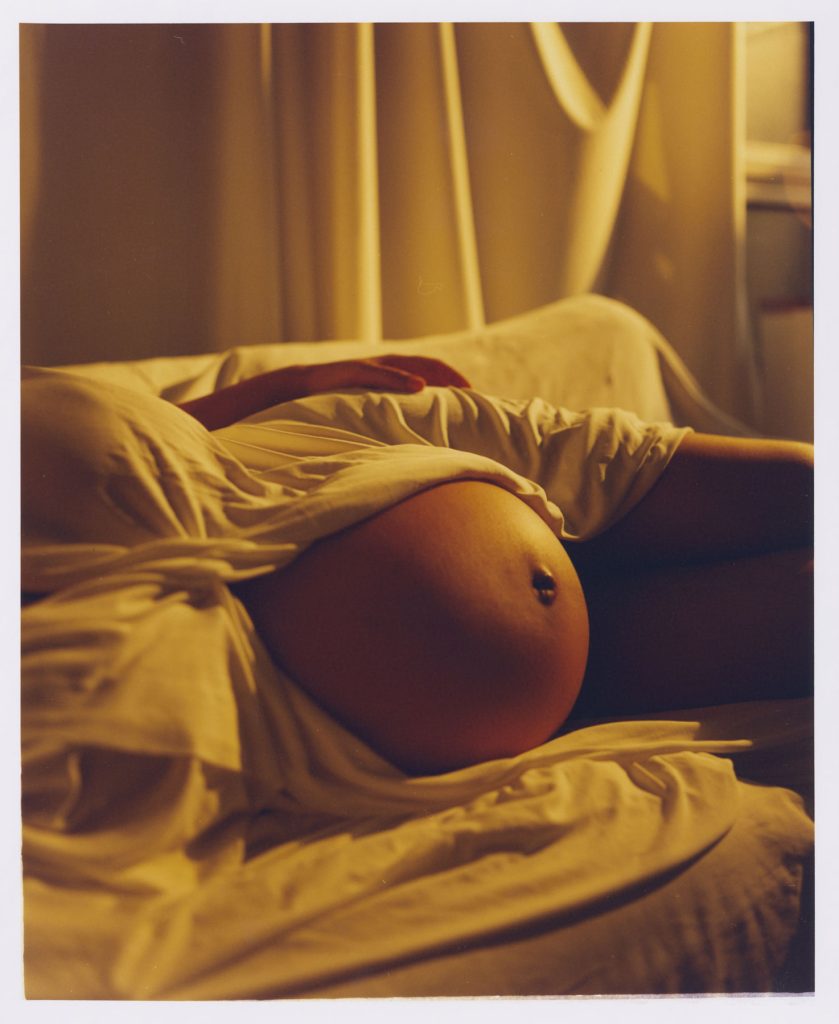

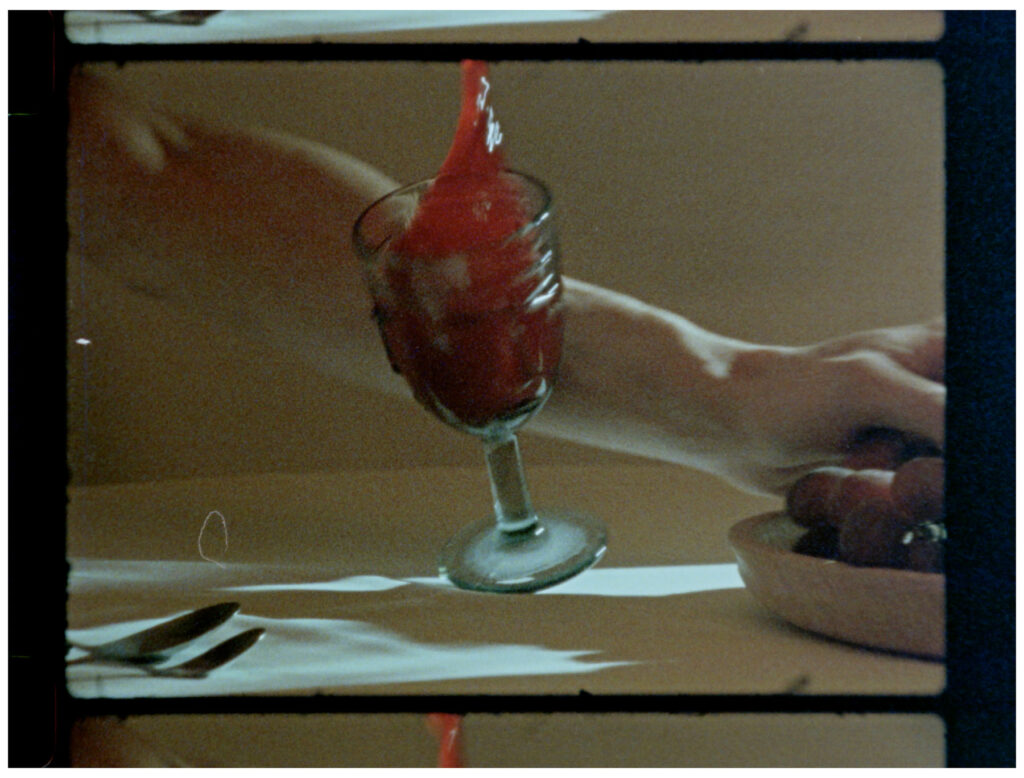

When photographer Bettina Pittaluga talks about developing film, she describes it as painting a picture – retrieving the details within the image, matching the exact skin tone of her subject. If the photographer finds joy in the technical processes of her work, it’s equally joyous to look at the final result. It is evident in Pittaluga’s photography that she approaches the development of each photograph in the context of its individual circumstance, ‘painting’ colour as it is most appropriate. In the broadest sense, her photography evokes a warmness, which Pittaluga communicates in different ways. Sometimes, her images are so dark that it’s only in the contrast of illuminated features that we see the subject, as in Pittaluga’s portrait of Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri for Le Monde’s M magazine. Elsewhere, her work highlights barely the curves of an upper arm, the contours of a profile, or the soft glow of a pregnant stomach. But other images can feel like an explosion of colour – a vivid red, or a minty green. It just depends on the natural lighting that the photographer finds herself working with.

Pittaluga’s photography is defined by the moment that it captures; natural lighting plays a part in that, but so does the emotional bond that the photographer forges with her subject. Regardless of whether she is working on commercial and personal projects, Pittaluga maintains that having a connection to her subject is essential. “My way of communicating does not change,” she tells NR, “I will always be looking for what the person wants to give me.” In a way, Pittaluga is sharing with the viewer what the person, or people, she photographs wanted her to see in the first place. The issue’s theme of celebration is an apt opportunity to contemplate Pittaluga’s work (or, rather, celebrate it) because every image is a celebration of some kind. Whether photographing a milestone – birth, love, and so on – or just capturing a moment that becomes immortalised by her camera, Pittaluga’s work is always a celebration of being human.

NR: There’s a warmth and intimacy to your work and the way you photograph people; is this an approach that you’ve always had in your work, or something that you’ve adapted over time?

BP: I don’t think I could take a photograph in another way. I think the way I photograph is intrinsically linked to the way I communicate; I need to communicate with the other person in order to capture them, in every sense of the word.

NR: You’ve previously mentioned the importance of forging a relationship with the person you’re photographing, whether that’s over a couple of minutes or much more established over time. But besides that, are there any other fundamentals that are important to a good photograph?

BP: I would say that the fundamental thing in a good photograph is to convey a truth; the reality of the moment. Of course, I need intimacy too, but I am always looking for truth. That’s the thing that want me to take a photo.

NR: When it comes to a composition, how much of the staging is a collaboration with the subject?

BP: I find my inspiration in reality, so usually everything is already there. I don’t prepare the set; it’s much more about lighting – natural light – which give me an idea of what I want. I also look for the shape and the form that I see with the light; the colours; the way the person is sitting or looking. Suddenly, it’s like I see something – I don’t know how to describe it because it’s very instinctive.

“When I am looking at the picture [afterwards], I can recognize the composition, but I would not be able to explain it when I am taking them.”

NR: What’s so compelling about your work is the fact that it doesn’t, as you say, look staged. It looks very natural.

BP: I love to shoot people in their own home because of that. I know that I will find something very intimate, not because of the intimacy, but because you can really learn about the person. Usually, I don’t know where I’m going to [shoot], so the only thing that I will ask is whether there is natural light that I can play with. But then it’s also a conversation. Sometimes people are like, “what should I wear?” and I always respond by asking, “how do you want to be represented?” I really want the person to feel comfortable and to be represented like this. And then it’s just about materials and colours – because the lighting is not the same with silver, or it’s not the same with pink or green. But again, it’s about the moment – it’s a feeling actually.

“The detail is the most important thing, it’s the emotion, which I cannot prepare in advance.”

It depends on the person in front of me. I’m following [them] in a way, I’m following what they want to give.

NR: You mention how different colours can affect the photo. Over the course of your time as a photographer, have you learned different techniques for using colour and how it will affect a photograph?

BP: I started photographing in black and white at first because I wanted to develop the film myself. I wanted to know how it works, so it was very important for me to oversee the whole process from beginning to end, when you have the pictures actually in your hand. People [had] said that it was very complicated to develop colour. And it’s really not the same process, it’s very long. But I learned how to develop colour two years ago. I think it’s true that I can see the evolution in my work [when] colour suddenly had more importance. Developing colour is like painting, it’s amazing. You have something neutral, and you can add the colours that you saw. At first, I spent, I don’t know, like seven hours on the same picture, just playing with colours, getting the exact colour of the person’s skin. By developing yourself, you can get great reds, or a really great yellow – so it’s true I am more obsessed by colours now than before. And it’s also about seeing colours with light – it’s a completely different world. Before, maybe I was seeing in black and white without knowing it, and now I can see colour.

NR: When you do the whole process yourself, it changes the way you feel about it – you don’t just press the button and wait, it’s the whole thing.

BP: I don’t take that many pictures because, with analogue, I only have ten pictures per roll.

“That’s why I love this process because it’s about taking time, I’m not in a hurry. “

Well, sometimes I only have one minute to take a photograph, but sometimes you can be really in the present and one minute feel long, so it’s how you take the time. That’s why I really love it also, it’s about taking time.

NR: It’s interesting that you describe developing colour film as being almost like a painting and it made me think, do you see your work as more being about reportage? Or is it more art?

BP: I don’t like labels and I don’t see my work as just one thing, but maybe I’m a portraitist? It’s more this way that I see my work, but it can be a lot of different things. It can be a portrait for press [work], or it can be more artistic. But I always feel poetic. No matter what the project, at the end of the day, it’s about human beings so, that’s why I think I identify more as a portraitist because most of my work is about human beings.

NR: The theme of this issue is celebration and I guess what’s lovely about your work is the way that it celebrates people, it celebrates the human form and the diversity of what it means to be a person. How do you feel celebration comes across in your work?

BP: Actually, I’m so glad you asked that. I think it’s one of my favourite questions ever and this is the first time that someone has asked. To be asked as a photographer to photograph a celebration of any kind – celebrating a child, love between two people, a transition: any kind of celebration. To me, it’s truly an honour. I think it’s the most beautiful thing about my job to be given this extraordinary trust and to be there together, to celebrate, because in a way, I am also celebrating that moment, you know?

NR: I think that ties in with something I wanted to ask you, which is that you’ve spoken previously about the concept of beauty and authenticity, whether that’s a relationship, or of a moment. How much of your role as a photographer is about being there, in that moment, and how much of it is just about pressing the button and waiting for that one shot?

BP: I don’t think you can separate one from the other. And maybe that’s what’s magical in the end – to be able to share the present together and look at it later in pictures. Usually now, with social media, we can take pictures all the time. [So as a photographer], it’s also about the fact that you cannot look at [the photographs] because it’s analogue.

“I cannot look at it straight after, so in a way, I continue to be in the moment.”

NR: As an analogue photographer, does having access to instant photography, with a phone and on social media, does it make you appreciate film more?

BP: I feel lucky to live in a moment of time when it’s so easy to take pictures. My cameras are very big and heavy, so I cannot have them [on me] all the time. To be able to take pictures anytime – and I film a lot because I like that an instant can last more than just a second, it can be longer. I love being able to record a long moment of softness or a long moment that I found beautiful. So, I’m always recording with my phone, and I love it so much, it’s amazing to be able to record so many things that inspire me in the day. No kidding, I think I have 30,000 videos [on my phone] and I buy a lot of memory. As a human being, it’s my way to express myself, to take 100 pictures of a flower in front of me if I want. It’s freedom. But with analogue, like I said, I really draw a portrait of someone, so it takes time and I love that.

Credits

Images · Bettina Pittaluga

https://www.instagram.com/bettinapittaluga/

Credits

Models · DAMI ADERONKE and CECILIA GIGLIO TOS

Photography · NICOLÒ PARSENZIANI

Fashion · DILETTA ARIANO

Casting · MATTIA MARAZZI

Set Designer · ALICE ARIANO

Makeup · CLARISSA CARBONE

Hair · ERISSON MUSELLA

Digital Assistant · DAVIDE LIONELLO

Fashion Assistants · DILETTA RIVIERA and ANNA BIANCHI

Credits

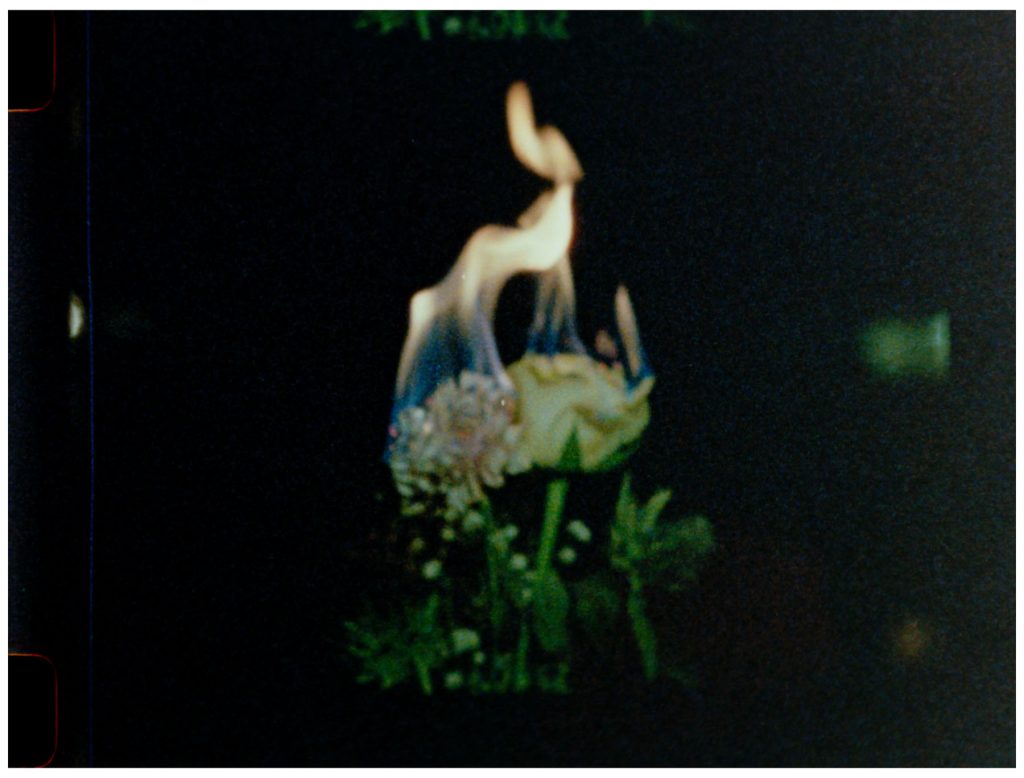

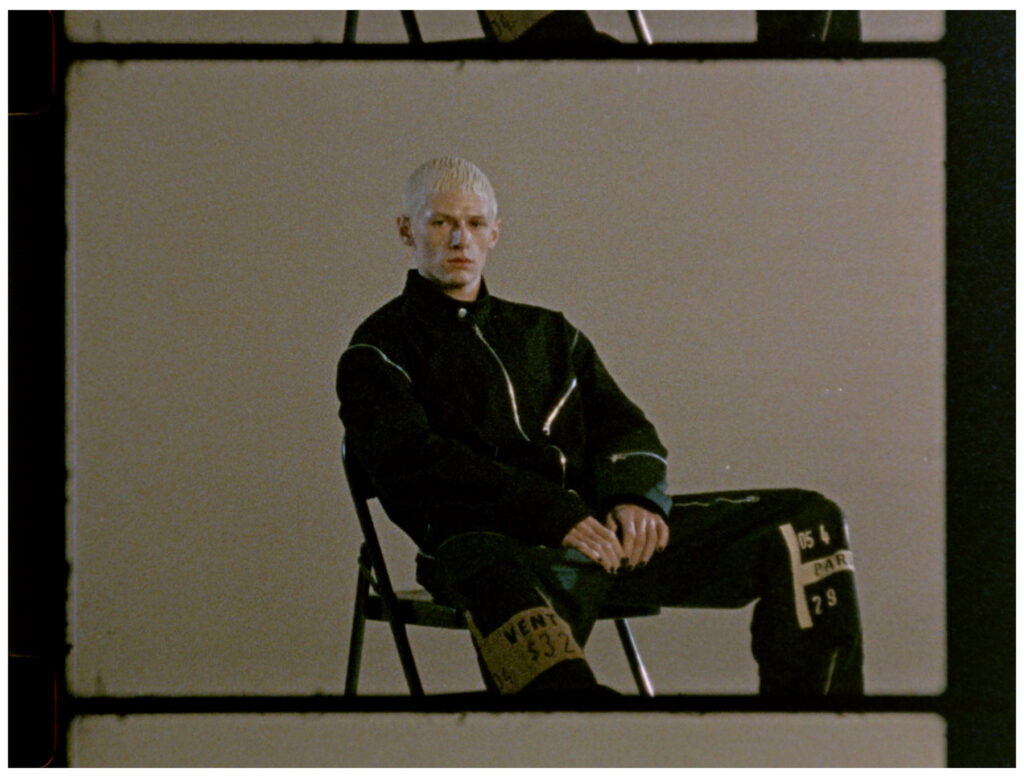

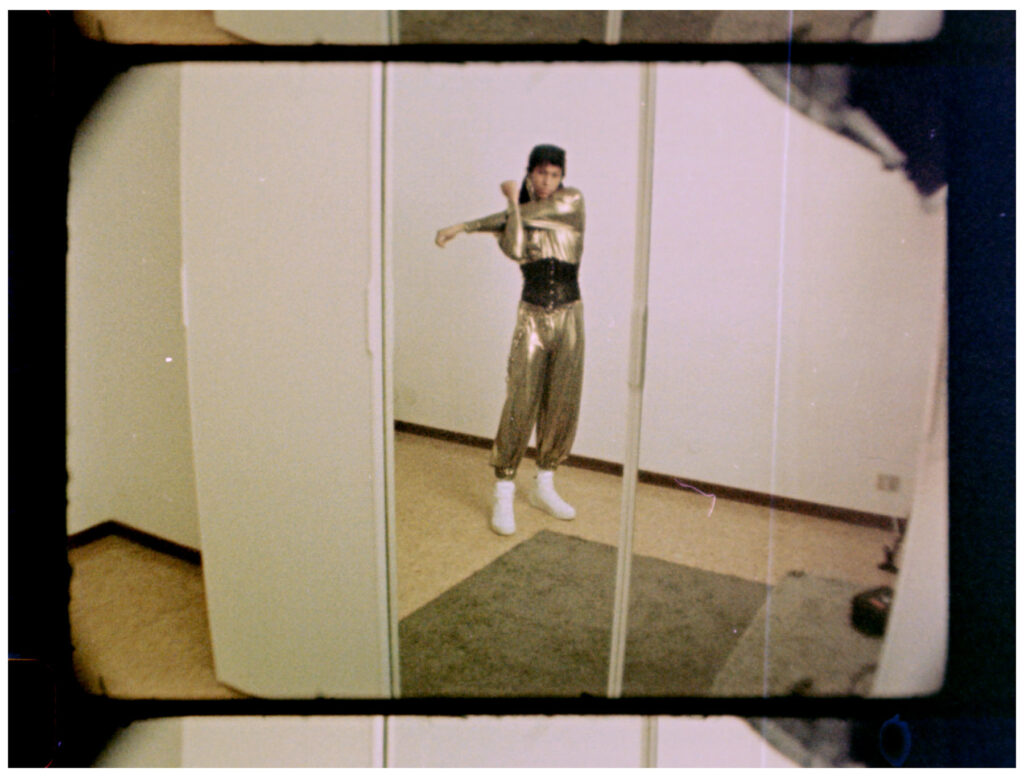

Director · FABRIZIO NARCISI

Stylist · ENRICA MILLER

Cinematographer · ALESSIO PANZETTA

Producer · BRYANNA KELLY

Fashion Assistant · DJORDJE VELIKOVIC, IVAN OBRADOVIĆ and MICHELA MONTANDON

Gaffer · PIERPAOLO MASSAFRA

Original Music & Sound Design · GIUSEPPE MAFFEI

Recording Engineer · NICOLA RECCHIA

Editor · JADE REMOVILLE

Hair · MATTEO BARTOLINI using BALMAIN HAIR COTURE

Make-Up and Prosthetics · GRETA GIANNONE

Make-Up Assistant · CAMILLA OLDANI

Casting · MONSTER BADD

Casting · Director POLLY PAOLA RUTA

With · JEAN, SOFIA CONOCCHIARI, JATHSON, GIACOMO GORLA, ELISA CICARDINI, CLAUDIA VERONESI, LORENZO BIGI, SARIAN SESAY, MIRIOS, SAMI, EMMA, LORENZO BELLI, LORENA SANTAMARIA, GIOSUÈ UGO, TAITU, LOLITA and PEDRO DE SOUSA

Film Developing · RICCARDO PASCUCCI

Film Scan · ANTONIO D’AGOSTINO

Shot on · KODAK SHOOTFILM 16MM

Credits

Photography · RAFFO MARONE

Models · DIANA SKOWRON at NEXT MODELS and HANNA KOBIALKA at FASHION

Fashion · MIRKO DE PROPRIS and VITTORIA ROSSI PROVESI

Casting · MATTIA MARAZZI

Set Design · VERONICA FERRARI

Makeup · FRANCESCA GUERRA using LORD&BERRY

Hair · PIERA BERDICCHIA at WM MANAGEMENT using BUMBLE&BUMBLE

Fashion Assistant · PIETRO CAVALLARI, REMI VANACORE and MORGAN DILDAR

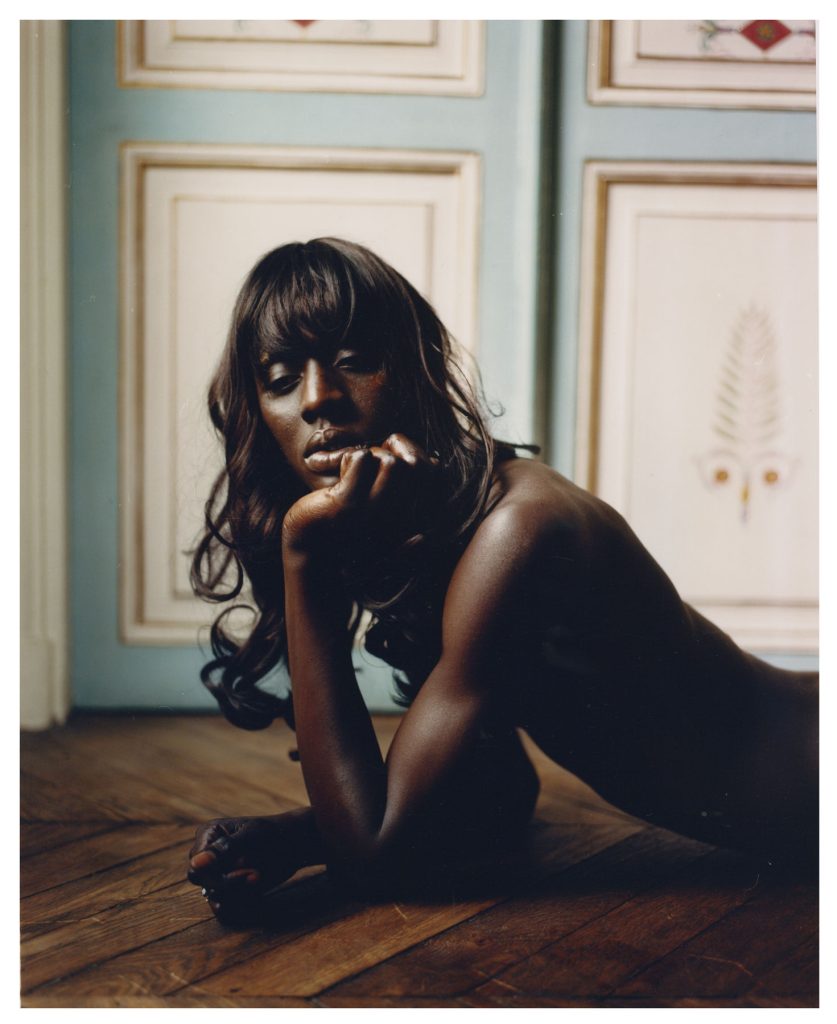

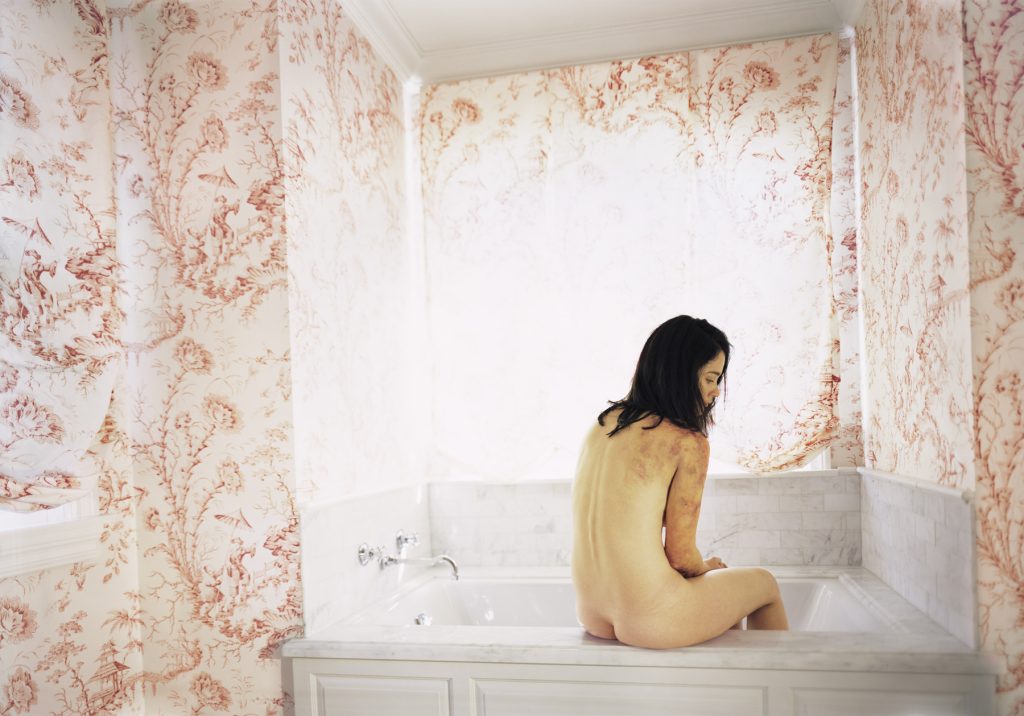

If Malerie Marder is something of a voyeur, her subjects are never unaware that they’re being viewed by the photographer, her camera and us, the audience. In fact, the subjects of Marder’s intimate work often know the photographer intimately herself. In Carnal Knowledge, a body of work published in 2011 spanning ten years, Marder photographed family, friends and herself – usually in a state of total undress, often in seedy motel rooms or within the interiors of suburban Middle America. Despite the voyeuristic quality that exudes in her work, Marder somehow pulls back from an overtly sexual image. Perhaps this is because of a mundane, yet alluring, encounter the young Marder had, as a photography student under Stephen Shore’s direction at Bard College in the early 1990s – one which would define her future practice. Marder was invited to photograph a family friend engaging in an illicit affair with a married lover in a hotel suite, using the techniques she’d just been learning at college. But if the lasting impact of that first commission speaks to the mise-en-scène of the photographer’s work now, so does the fact that the lover, after the affair ended, demanded for the negatives afterwards. “I’ve been trying to re-create those pictures ever since,” Marder told Artforum in 1999, “simply because they were worth burning.” Naturally then, some of Marder’s images verge on the erotic – capturing a moment that feels, as the viewer, like an intrusion. As the photographer tells NR, there’s always something of a mystery within her work, where it’s not always quite clear what is going on.

But Marder’s work is never accidental, and often staged. This is most obvious with pictures that seem to make direct reference to art history; take Bath House (2001), for example, in which a scene of (majority male) nude bathers are positioned in such a way to recall one of Paul Cezanne’s paintings of bathers from the late nineteenth century. More recently, Marder’s second body of work, Anatomy (2013), plays with art historical references for different effect. The series, taken over four years, sees Marder photograph sex workers in Rotterdam, positioned in different settings within the private spaces in which they work. If Anatomy captures an intimacy like Carnal Knowledge, it’s less the fact that we feel like we’re intruding on a private scene, than a behind-the-veil glimpse into the lives of these women – the spaces they occupy, the relationships they make with one another, Marder, and the camera’s lens. In one image, Marder’s subjects are positioned in a way that recalls Henri Matisse’s La Danse (1910) – but if that painting has a joyful lightness to it, Marder’s photograph, in response, is more grounded. And perhaps that’s where the essence of Marder’s work lies; between the emotion that the sight, or the thought, of the nude body evokes, and the candid nakedness that we really see.

NR: Since that first encounter, shooting a family friend and her partner, (how) has your approach to photographing changed?

MM: I think that first encounter showed me what an illicit affair actually looked like. Those are the moments I centred on – the explosion of emotions, the secrecy, the desire — the fact that I was actually able to capture that when I was in the whirlwind of what was unfolding showed me I could perform under pressure. I think my set ups have become more tactile and I can more easily identify what I’m looking for, but the more comfortable I become, the more I push myself. I try to transcend what I’ve done. There’s always resistance, both externally and internally, but this is universal. This is not just endemic to me.

NR: How do you negotiate with your subjects when taking their photograph? How much is staged by you, and by the subject themselves?

MM: I decide on the setting and then we both figure out what comes next. Some of it is more choreographed by me, but usually I end up capturing an aspect of them that is revealed.

“It’s like writing — you have a sense of what you want to say but you haven’t yet written the words.”

NR: What informs the setting in which your subjects are photographed? Do you choose a location depending on the subject, or vice versa?

MM: Both — sometimes I’ll see a place and wait for the perfect person to match that character, or I’ll meet someone and try to hone in on where I should photograph them. I find people are more fascinating than most places, so settings are harder to procure.

NR: How does ‘celebration’ tie into your work; if you were to ‘celebrate’ something, what would that be?

MM: That is a genuinely a fascinating question. I like the idea of celebrating people’s beauty. I’m a fanatic about light and I like there to be a certain mystery — I feel both create a kind of romanticism, even if it’s on the melancholy side. But that does not mean it is any less of a celebration. We only have a short time on this planet and it’s impossible for me not to be in touch with people’s pain… So maybe I’m celebrating people’s vulnerability and softness…

NR: Something that has been said of the Anatomy series is the lack of ‘you’ being in the work; how important is it to have a relationship with your subject, and is it important that there is an element of “self-portraiture” in your photography?

MM: It’s only important when I’m purposefully playing a part in the picture. Often times, I end up being in the picture and I’m just part of the shadow… helping the image along, but then there are times where it is more compelling for the viewer to know it is me.

“Self-denial plays a large part of what I do; I sincerely doubt I am in any of my pictures.”

NR: In terms of creating an image, how does colour (or its absence) play into your work?

MM: It plays a big role. For me, black and white is more like a sensual memory and colour is closer to present tense. So, when I try to create a dream-like state, I find it easier to say it in black and white. I still attempt to do this in colour as well. I group images by colour, and certain colours mean certain things — or elicit certain emotions or feelings. I try to saturate as much colour into an image as possible even if it borders on garish. A little like how Douglas Sirk filled his compositions in “Imitation of Life” with flowers — one long funeral. I am not sure what the saturation of colour means, but I think it is my attempt to overwhelm reality with as much beauty as possible — otherwise the darkness creeps in. You can still see it, of course.

Credits

Images · Malerie Marder

https://maleriemarder.com/

Credits

Models · Ara Ha (Fabbrica Milano), John Godswill (The Claw), Igor Szymanski (Why Not Models), Rashida Mamudu (Select Model Management)

Photographer · ALESSANDRO MANNELLI

Stylist · MARCO DRAMMIS

Makeup · ALESSIA STEFANO

Hair · ALESSIA BONOTTO

Casting Director · IRENE MANICONE

Stylist Assistant · ROCCO COLLAZZO

Stylist Assistant · GIULIA BASILE

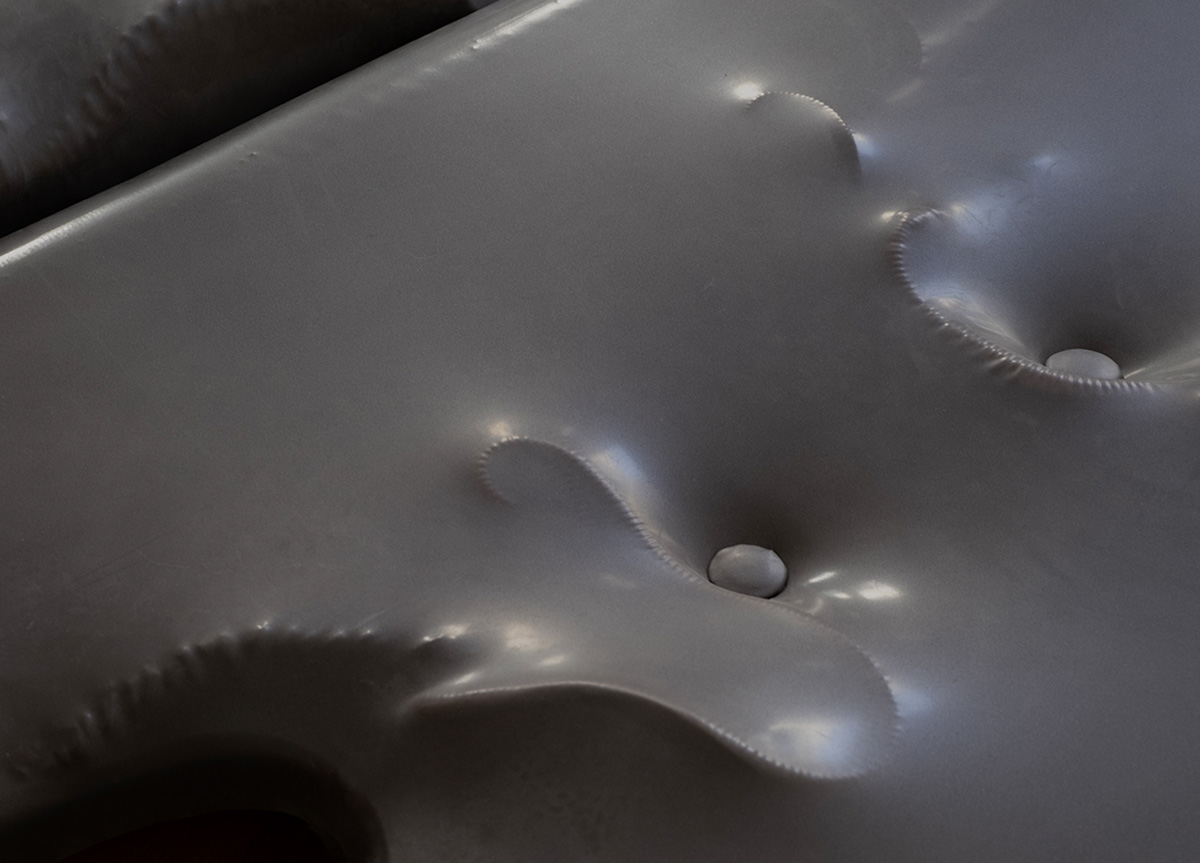

For the artist Laila Majid, exploring the relationship between materials and the body is a recurring theme. Her artwork, Rosie (2019), for instance, is a close-up shot of the imprint of a trainer on the calf of a friend’s leg having been sat cross-legged for a period of time. The markings of the shoe and stitching of the fabric are punctured by the ever-so-slight presence of hair regrowth – the effect is an almost surreal investigation of the similarities between the two surfaces (the now-absent trainer; the skin after wear). Rosie was exhibited as part of the Nude show at Fotografiskia, Stockholm, as well as being selected for the prestigious Bloomberg New Contemporaries show in 2021, with Majid explaining in an interview for the exhibition’s platform that, by “morphing [the body] into a new and unfamiliar form” what we think of as being real is destabilised. That much is apparent in Crease (2021), exhibited at the Slade School of Fine Art MA degree show, in which a black and white photograph of what appears to be a fairly innocuous antique chair, on closer inspection, features erotic mouldings.

The artist is now studying Film Aesthetics at the University of Oxford. It’s a logical step for Majid, who often turns to video and film in her practice – “I’ve never studied film in such a focused way before,” she tells NR over email, “so it’s also helped me to dig deeper into current interests.” In particular, the artist has been “looking into the close-up shot, and the relationship that this sort of shot has to both intimacy and abjection (as facilitated by the camera’s proximity to that which is being filmed).” In previous video works such Macro (2020) and concave/convex (2018), Majid furthers her investigation of the body – animal and human, respectively. In both pieces, the natural surfaces of Majid’s surface (fur, saliva, tongues) take on an almost unnatural quality, creating an interesting counterpoint to the way in which the artist grants synthetic fabrics, by contrast, an organic quality. By turning to a range of materials, mediums and methods throughout her practice, Majid’s work challenges, or distorts, the boundaries of that which we might think of as being diametrically opposed: to that end, how concrete, and how different, are what we think of, or see, as being ‘real’ or ‘alien’?

NR: Am I correct in thinking that Rosie is printed on latex, which makes me wonder how the layering of material features in your work?

LM: Rosie is actually printed directly to vinyl, the printer however uses latex inks (commonly used to produce banners, outdoor signage, etc.) Although the work isn’t printed onto latex, this is a material which I frequently use in my work, and one that I always seem to come back to. I’m interested in the close relationship between latex and the body. It is a stretchy, skin-like material that, in its use as a material of fetishwear, sits directly on the surface of the body, fusing to the form of the wearer in a moment of sweaty skin-on-skin contact. I think this speaks to a layering of surfaces that you bring up. Latex definitely operates in this way; as a non-porous material often used to craft tightly fitting garments, it effectively sticks to and becomes an extension of the body of the wearer, and an extension of the skin itself. Layering, in this case, works to facilitate transformation through dress (change in appearance and physique/sexual release/role play etc.)

NR: What is your process of working with, and sourcing, different materials? And how do you navigate working in different mediums?

LM: Sometimes this is quite an intuitive process, of feeling seduced by the physical properties of a given surface. I also think that it’s important to pay attention to what an image or object may need, be it a specific surface or printing ink. With Rosie, for example, I knew that the image needed to be printed on vinyl given the connection that this material has to window displays and advertising.

“I’ve always felt it important to approach image and surface in such a way whereby they feel bonded or dependent on one another.”

NR: You recently had a joint exhibition, not yet, with your on-going collaborator, Louis Newby at the San Mei Gallery – what does the process of collaboration, more generally, look like for you?

LM: I’ve always been drawn to collaboration given the potential to enrich one’s work through the inclusion of new voices. This was much the case with the video piece in not yet, where we worked with different collaborators who were able to contribute to and elevate the work in various ways, through animation, sound design and AI programming.

NR: And, in terms of your work with Louis Newby, how do you navigate your separate artistic practices to create collaborative work, and a joint show?

LM: Our collaborative practice truly sits in the space between our separate practices. Louis and I have spoken before about the idea that our collaborative work depends on our own practices/individual interests to take shape in the way that it does, and yet does something different to each of our practices as it sits between the two.

NR: Found objects (film, comics, journals) feature in not yet, whilst your Instagram account combines your work, personal photography and other imagery – does the concept of the archive, and the act of archiving, feature in your work?

LM: Instagram is tricky, I can never really figure out how to use it. For now, it exists as a combination of different sorts of images, as you’ve described. I also struggle with the app given its harsh terms and conditions and censorship rules. Instagram aside, images have always been important to me. They feed directly into the work I make and are an invaluable source of research (found images, pixelated screenshots, scans of images from magazines, my own photographs). I enjoy the process of collecting images, perhaps this act of collecting can be thought of as archival. Louis and I also have a shared archive of found images pulled from a vast array of sources which we use to generate print works.

NR: How do you negotiate the human body and other animal forms (real, imagined) in your work?

LM: One thing that immediately comes to mind is the undifferentiated body – a form that points to a potential growth/change/development. I find it interesting to think about how one could present a moment of transformation— how a still image, for example, could hold this moment.

“When does one body morph into another, or suggest a form exterior to its appearance?”

This is something that you often see in science fiction/supernatural horror – for example, at which point does the arching of the spine/contorting of the body tip into an anatomical language that suddenly becomes unfamiliar? I’ve been thinking a lot about [Soviet film director and theorist, Sergei] Eisenstein’s idea of ekstasis in this way, which he explores as a transition ‘to something else’, from one state to another (‘to be beside oneself’).

NR: You’ve spoken previously about seduction and repulsion in relation to beauty – how do these two, supposedly opposing, concepts feature in your work more generally?

LM: I think I focus more on how the two come together, in such a way that they rely on one another to produce a specific effect/affect. I suppose that seduction and repulsion go well together in that their marriage can be used as a tool to reconsider beauty. Pushing oppositional forces together within the same pictorial space also creates tension; it’s a combination which unsettles. I don’t think this is necessarily specific to the seduction/repulsion relationship, but in broader terms I’m reminded of the movement of the body during pleasure- contorted, arched, muscles clenched on the one hand, and giving into total pleasure and bodily sensation in a moment of release on the other. I’d like to situate my work within a moment like that, one which teeters on an edge between oppositions.

Credits

Images · LAILA MAJID

https://lailamajid.net/

The construction of a new system, a new process, and a new language marks the beginning of Juan Carlos Sancho and Sol Madridejos’ work at their Madrid-based practice Sancho-Madridejos Architecture Office, established in 1982. Gazing upon their architecture and design, the structure bends and folds, an inquiry on the limits of the materials. The flexibility of the duo’s minds materializes into products of architecture and designs that they have developed, a signature that now lines their ethos: the concept of fold.

The analysis of each item starts with what they call a base-fold – the foundation that contains all of a project’s required DNA – that generates a process tailored to the work, defining a line, an identity, and a language of its own. The spatial quality becomes elevated, enhanced by the structure’s relationship with light, orientation, or location that swings from one criterion to another. “From this starting point, many of the pieces are prone to a specific location or a specific time, bringing out variables from the context which we sometimes only discover later on. These processes are not linear since each step has a permanent effect on the rest,” the duo states. For NR Magazine, the concept of fold coincides with the concept of celebration.

NR: I would love to start with the idea you developed and grew: the concept of fold. How did it happen, and what kind of research did you have to go through to materialize this?

SM: We have worked with the concept of fold for the past 20 years. It all began with an interview with the sculptor Eduardo Chillida, during a walk in Chillida Leku, where his works are exhibited. He told us that ‘the fold creates a spatial, formal and structural unity’ and that ‘the fold creates spaces.’ This encouraged us to investigate the role it had to play in the field of architecture.

In this part, could you guide us on how the concept of fold works?

A fold works as a formal-spatial unit. This is the core concept of a fold. Not everything that folds is a fold; it can also be a pleat.

The process reminds me of origami. Are there cultures that influence your work ethics and design flows? How do you infuse them into your projects?

A fold is not origami. It can seem like it, but it is basically the opposite. To fold is to generate a strain, an action, a cut on a plane, and study how it transforms topologically because of this action. It is easy to confuse them, but they are nothing alike.

You mentioned that your process touches upon a unique spatial quality that is enhanced by its relationship with light, orientation, or location. Without one or two of these elements, would you say your space would be incomplete? How essential is it to form these three elements into a single force?

“Form, space, and structure along with light, location, scale (the human being), and material, form the single conjunction of a fold.”

If any of these variables are missing, a fold is incomplete and does not work. They all carry the same weight and deliver specific qualities.

Could you elaborate on this statement of yours: These processes are not linear, since each step has a permanent effect on the rest.

These processes are laborious and take up a lot of time. In our office, we have around 500 different fold models with some of them very alluring, but not all of them are folds; some are pleats.

“A fold has, in the first place, to answer to mechanical behavior. It has to be structural and coherent by itself. Once this is the case, work can continue.”

As we focus on Celebration, I’d love to know how you celebrate creativity and architecture outside of your office?

There are several levels of celebration. First, seeing a finished work moves us, and that is the first celebration. This is best enjoyed among the people that have taken part in the design and the construction processes.

Taking photos of a finished building and participating in the photo essay also stimulate us as we get to see the project from other positions and points of view.

Friends and architects visiting a building enriches the perception of the project.

Finally, its use by the client is also a celebration, seeing a building in use complements its own meaning.

Credits

Images · Sanchos Madridejos

https://www.sancho-madridejos.com/