“I’ve felt this for a while about technology – that it’s inducing this strange kind of medieval state, in the sense that they cohabited two realms between the spiritual and the profane.”

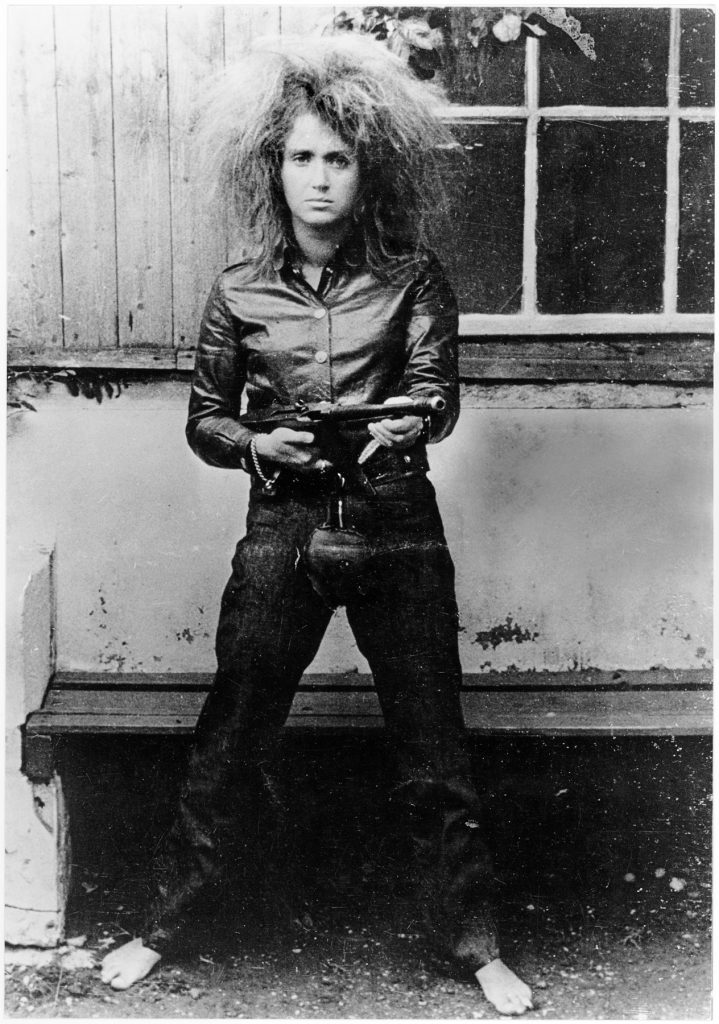

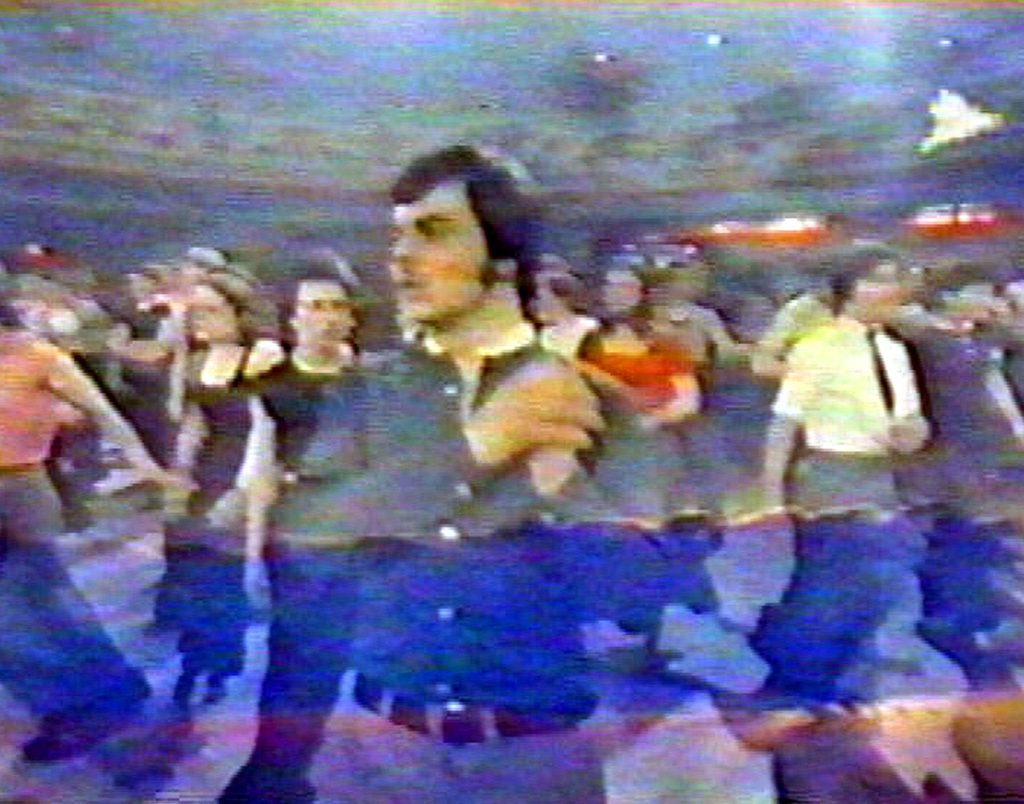

“Ah rabbit holes, I know them” texts Mark Leckey, after I ask if we can delay our interview. I have a list of questions I could put to the artist, but I’ve lost myself in the matrix of his work. And where do you start? Perhaps with Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, the 1999 video that put Leckey on the art world map. But that isn’t the beginning of the artist’s story, something the artist himself has subsequently explored. Leckey grew up in Ellesmere Port, a town used as an overspill for Liverpool in the late 1960s that looks back towards the city on the other side (the wrong side, Leckey would say) of the River Mersey. Leckey studied art in Newcastle, moved to London and, having not found success, decamped to the States for a while. Leckey has spoken previously about how, in the mid-to-late 1990s, he was interested in the music videos that were coming out at the time. But Fiorucci, the result of that intrigue, was less MTV and more ICA. And it was at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London that the video was first screened. Fiorucci, with its thumping music over a montage of found footage of Northern Soul dancers and hedonistic ravers, may have since entered the domain of British art, but the artist didn’t become a household name at the time. That arguably came later in 2008, when Leckey won the Turner Prize for his exhibition Industrial Light and Magic at Le Consortium in Dijon, France – a show which concretely outlined the recurring themes that have since come to define his practice, in which the post-industrial landscape of his youth and the emergence of an alternative, quasi-digital landscape in its place, are recurring motifs.

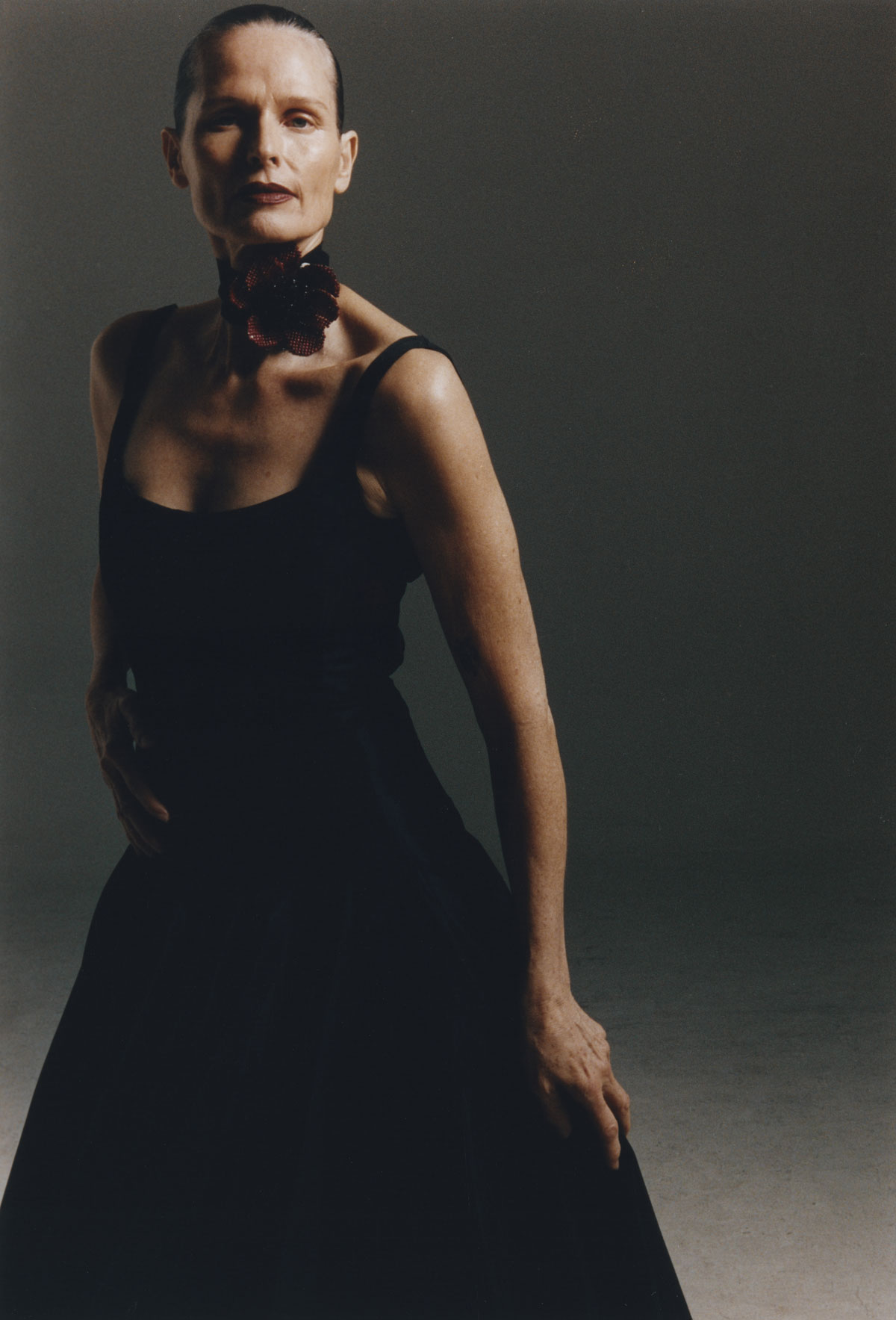

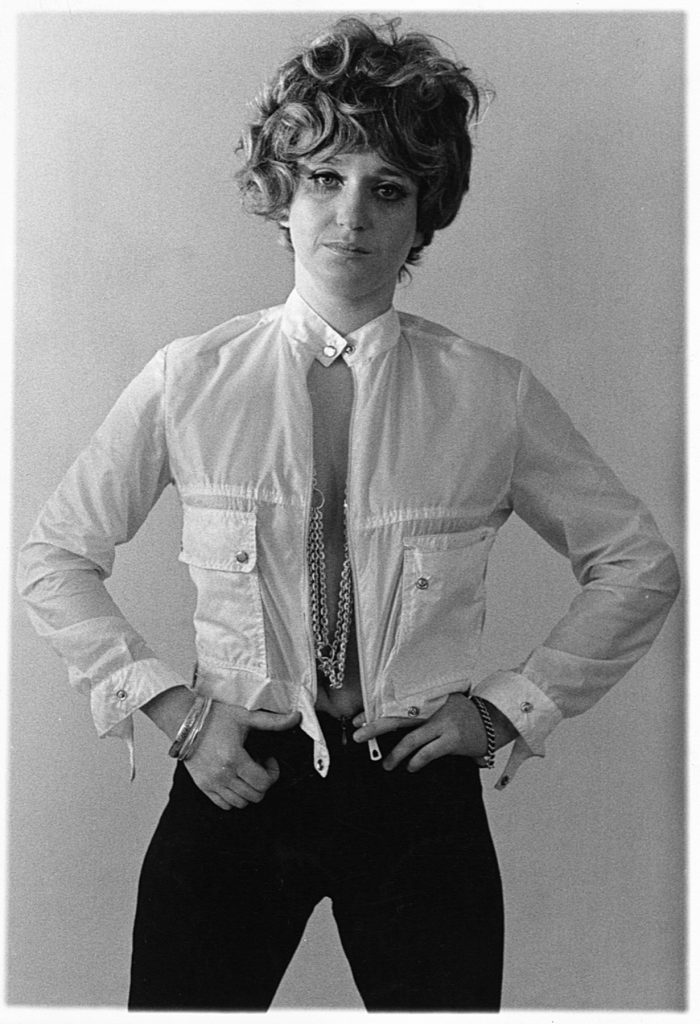

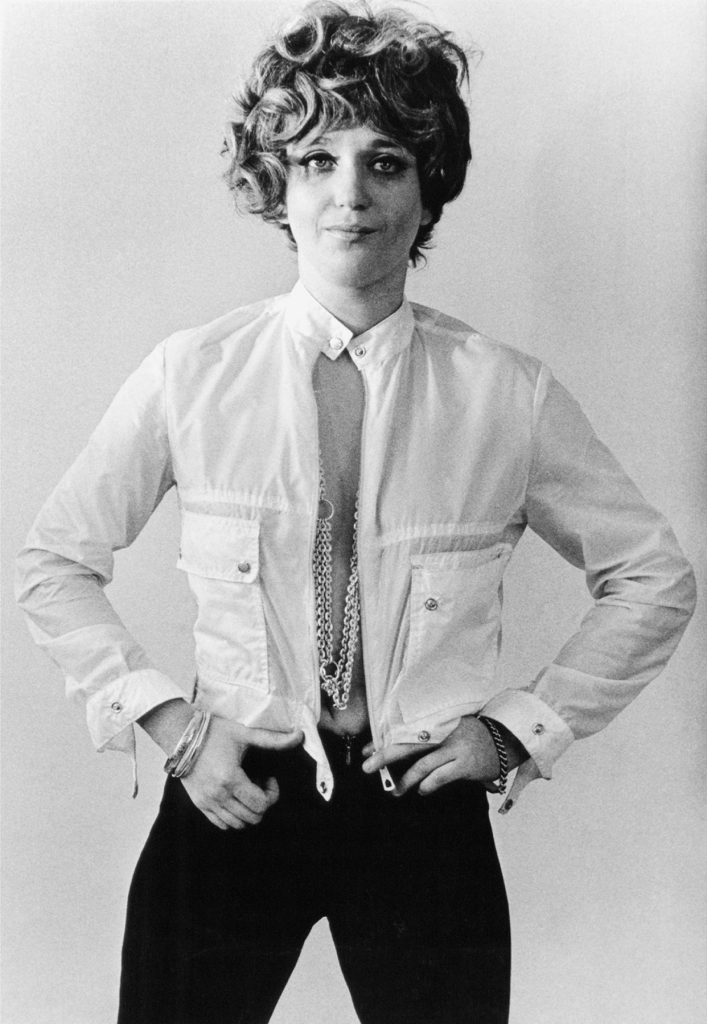

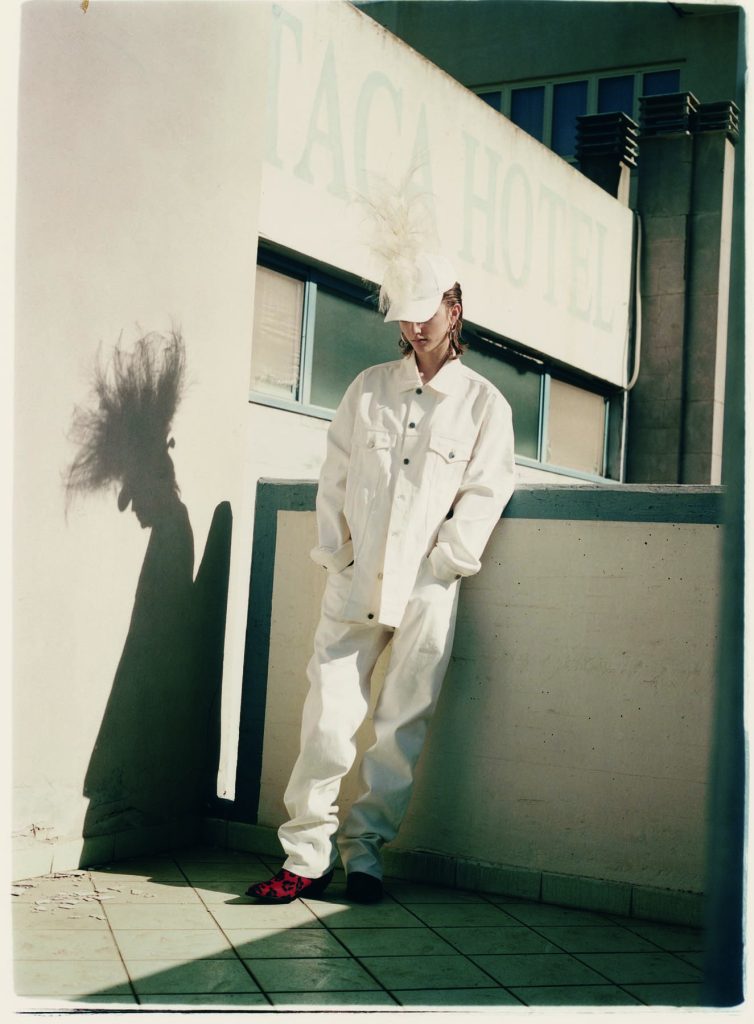

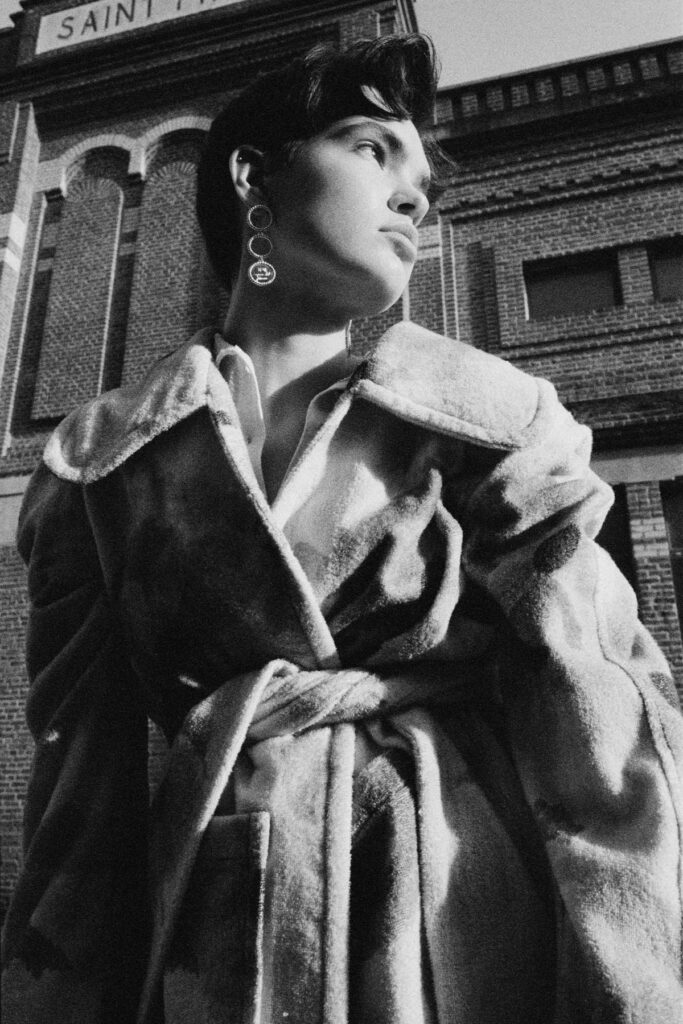

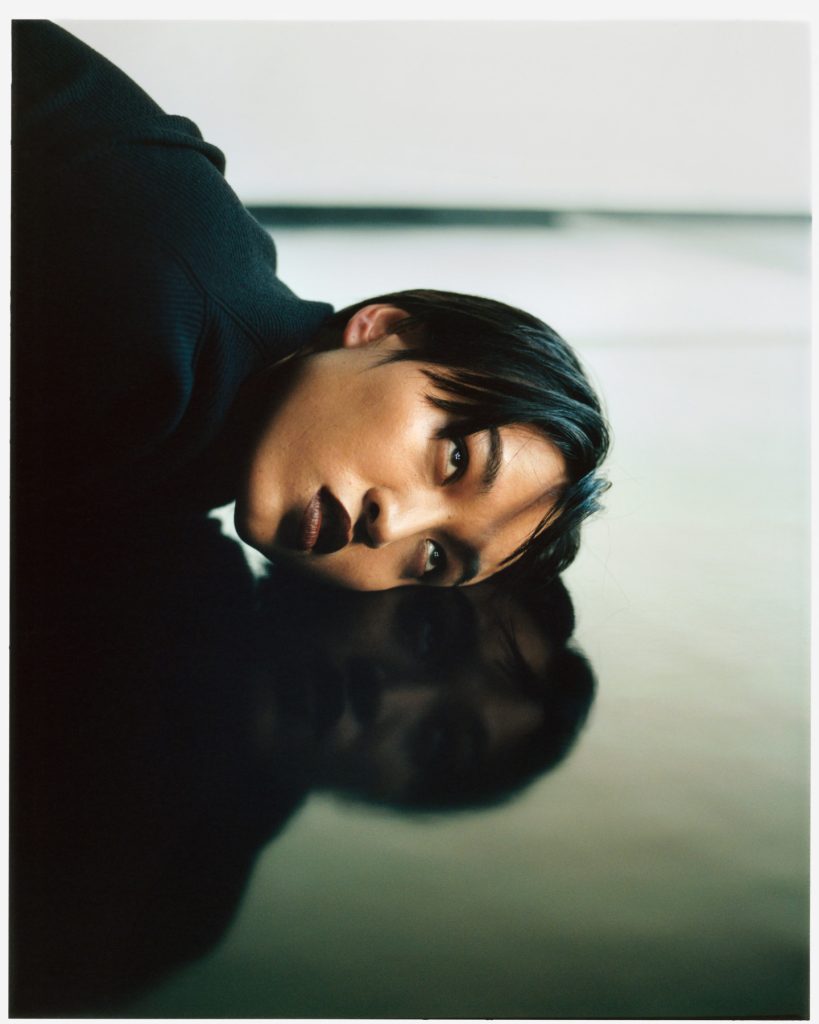

A week later, I meet Leckey – wearing a full-length white fur coat, matching plaid shirt and bottoms, and his signature pearl earring – at a pub near the artist’s North London home. Originally, our interview was scheduled to take place on Zoom, but I have a hunch that the rabbit-hole questions I have prepared could better benefit from meeting Leckey, a self-proclaimed hermit, in person. And over a pot of tea, we begin by discussing the art world, the internet and what it means to be a working-class art student today. It’s a topic Leckey has pondered over for a long time, but now, he suggests, if he were in his early twenties, he’d be prioritising NFTs over art school. “I don’t think NFTs are just bad drawings of monkeys,” Leckey says – there might be more to it than that. And if there’s a novelty to NFTs now, the German electronic band Kraftwerk seemed novel, too, at first. “You don’t know what the tail of that is going to be, or the direction it will go.” It’s in no way surprising that Leckey is thinking about NFTs, even if he says he is sceptical because of the environmental arguments made against them; he’s been dubbed the ‘artist of the YouTube generation’, and an art career spent scouring the internet for soundbites and videoclips to use in his work means that, naturally, Leckey is all too aware of what’s happening online. But, having rewatched Fiorucci on YouTube rather than the gallery setting it was made for, I wonder if the artist now considers his work to be made for the internet, or still to be absorbed in a physical environment?

“Both, I think. I like the immediacy of putting something on Instagram.” Leckey has an upcoming show at Cabinet Gallery in South London, and so when that opens, he will also share the work on social media. But using Instagram doesn’t necessarily give Leckey a clearer indication of what people think of his output. “People can go ‘fire!’ or whatever,” he says in relation to the emoji – one of eight pre-set reaction emojis that Instagram suggests for its users in the comment section. “[But] I don’t know why they liked it. And then you can have an opening and people just sort of nod as they walk out the door – so I can’t gauge any response from that.” Fiorucci was one of the rare occasions Leckey got an immediate reaction, with people coming up to the artist and telling him what they thought of the piece. “And then, nothing happened,” he says of Fiorucci, “it slowly percolated. But it got its maximum impact twenty years later, around 2019.” The resurgence of interest in Fiorucci coincided with a huge show at Tate Britain, O’ Magic Power of Bleakness, in which the artist recreated a motorway bridge from the M53 in Merseyside to go alongside a new video work, Under Under In.

But it was also around this time that rave culture of the late 1980s and 1990s enjoyed something of a renaissance. Perhaps that yearning for anything closely resembling the rave scene could explain the sudden interest in Fiorucci, even if the other side of it – Northern Soul – remains firmly in the domain of a particular vein of Northern working-class culture. Nostalgia is something Leckey often speaks of, so I wonder if he sees the renewed interest in Fiorucci’s depiction of rave for a younger audience as (misplaced) nostalgia? “Yeah, but then, it’s not,” he says. Growing up in the eighties, he was nostalgic for the sixties, the equivalent decade for today.

“Woodstock and all the rest of it seemed impossible, and I guess that’s part of the thing with rave. It seems both exciting and intoxicating, but also depressing.”

Leckey describes modern-day nostalgia as a “contemporary condition, of technology, of capitalism.” That much is evident in the 2015 video, Dream English Kid, 1964 – 1999 AD, in which the artist used found footage to recreate his childhood, having seen a clip online of a Joy Division concert he’d also attended in his youth. By using found footage, clips from television shows and a 3D rendering of that same M53 bridge, Dream English Kid doesn’t depict Leckey’s own childhood per se, but reconstructs a kind of collective memory. In that sense, he describes nostalgia as being algorithmic in a way; “it’s like data passing through your body.” An equivalence could be gentrification, “in that, as an artist or whatever, you’re just moving into space, blithely unaware of where you’re leading society.” So when it comes to nostalgia, Leckey says, “you’ll connect with these things in a very real way, but you’re actually just at the forefront of clothes manufacturers and all the rest of it that are going to come in your wake and exploit that.”

There’s a bit in Fiorucci where a voiceover lists off clothing brands – Fiorucci, of course, but also Lee, Fila, Burberry, Slazenger, Lyle & Scott, Lacoste and Aquascutum – to name just a few. These were the brands of choice for the Casuals, a subculture of football supporters in the 1980s associated with designer gear and hooliganism (Leckey was, for lack of other entertainment, a Casual for a period in his teens). And like return of rave to popular culture, the brands that defined the Casual’s Terracewear seem to have seeped back into the collective consciousness, too. But, anyway, it takes a few listens to fully grasp the brands that are listed in quick succession in Fiorucci, the voiceover taking on a rhythm that seems to mimic the hardcore beats that Leckey samples throughout the video. Was that deliberate, on Leckey’s part? “I think when I did that, it was more out of embarrassment,” he says – “because it was me and I didn’t want my voice on it. So, I pitched it down and put loads of reverb on it.” The result was something more akin to an incantation. “And I suppose Fiorucci is about conjuring up a religious experience.”

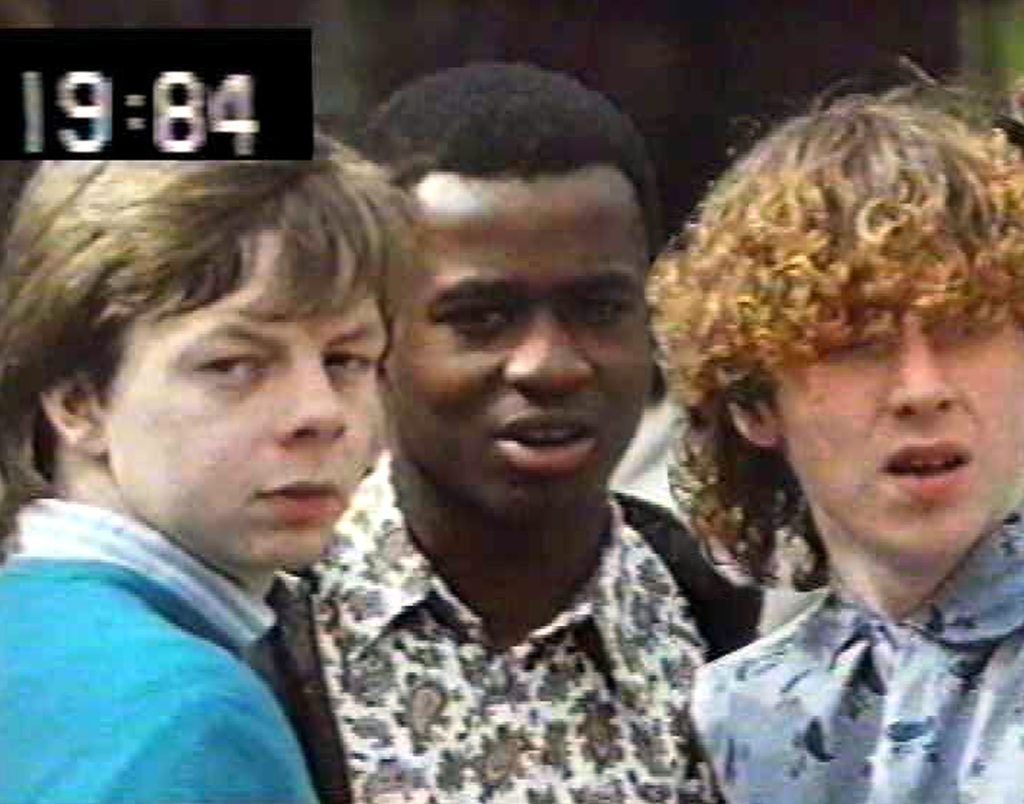

Under Under In also plays on the idea of the almost religious dedication that is afforded to brands. Across five separate vertical videos that seem to mimic the world seen through Snapchat, we’re introduced to a group of kids at the centre of the film, their identity fixed in the brands they wear: Nike Air, Adidas, C.P. Company, North Face. “We’re Stone Islanders,” one boasts. But these kids also seem to betray their youth, drinking a £1.29 Maltesers drink, the sight of which might elicit a Proustian madeleine moment for anyone attending an English secondary school near a corner shop in the twenty-first century. The kids also recite the names of car brands they’re too young to drive, let alone own. But if Under Under In can be seen as a Fiorucci equivalent for a subsequent generation, Leckey thinks that the moment of brand affiliation as self has passed. “I read something really interesting about subcultures in the twentieth century,” he explains “and essentially how using consumption to define yourself has been wholly exhausted.” Now, it’s through opinions, not brands. “I listen to that bit in Fiorucci now and to me, it seems almost quaint.”

If the world that shaped Fiorucci and Under Under In has moved on, Leckey’s work continues to be a source of inspiration for others. There are 327 comments on the Fiorucci stream on Leckey’s YouTube channel – musings from the artist himself over the eleven years since it was first uploaded, and from viewers recalling the first time they saw the film, or the memories it evokes. In one comment, a user asks if they can sample part of Fiorucci. “It’s all part of the Creative Commons. Get in there,” Leckey responds. Soundbites from Fiorucci previously made their way into Jamie XX’s 2014 track, All Under One Roof Raving but, I wonder, so much of Leckey’s work is gleaned from what he finds online – how does he feel about others doing that with his work? “I wish they did it more!” he exclaims. “I mean, it’s just stuff really and it’s there for the taking.” Leckey describes found footage as being a surrogate that allows him to communicate something. “If someone can do that with my work in the same way, then that would delight me.”

In last year’s To the Old World (Thank You for the Use of Your Body), Leckey repeats, reconstructs and deconstructs a ten second video he found on Twitter over the course of almost nine minutes. The video clip sees a boy take a run up before jumping through the side of a bus stop, his friends, out of shot, laughing (in shock? out of amusement?) as he crashes onto the floor surrounded by glass. But what was it about that clip that was so compelling to Leckey? “I always try and avoid drawing in theory, partly because I’m going to do it really badly, but it’s that Roland Barthes book, Camera Lucida; there’s something in that image that draws you in and connects in some way.” That could be, say, “some hi-res, beautiful, well-shot image,” but in Leckey’s case, it’s “some piece of shit” that affects him so resolutely. “And it’s like, why? What the fuck? Why is this making me feel anything?” He’s been thinking a lot recently about something the sci-fi writer, Philip K Dick, said: the symbols of the divine initially show up at the trash stratum.

“So there’s God in the midst of this shitty piece of videotape of this stupid kid.”

But that stupid clip of that stupid kid resonated more deeply with Leckey – after all, his work is usually, in some way, autobiographical. “As soon as I started watching it, it was like, I did shit like that when I was young.” But whilst Leckey’s work connects with lived experience, the process of making the video is as important. If Leckey set out with different intentions when he began making Fiorucci (it was, he says, intended as a kind of documentary), it quickly became about the medium itself. “I was looking at these VHS tapes and a strange intimacy and distance developed as I was watching. Something about the footage compelled me to look closer into the ghostliness. I’d find myself wanting to merge with it, but at the same time it’s continually pushing me out and repelling me because it’s a ghost and it’s the past – and it’s impossible.” To the Old World comes from a similar place – of simultaneous intimacy and distance. “We live in this continuously mediated space, and all I feel I can do is try and find some intimacy or immediacy in that.” It’s somewhere in this space that Leckey thinks we now reside, where memories and the present exist on the same plane. When it comes to the video clip from To the Old World, “I can be that boy jumping through the bus stop, I can one of his mates watching, and I can be me watching them, watching him. I can be all these things at the same time.”

To the Old World, which was commissioned for Art Night and toured the UK in autumn 2021, followed a period in which Leckey – like many throughout the pandemic – struggled to make anything, let alone the video. But, he says, he began to see the bus stop in the clip as a sort of portal. “I look at it now, and realise it’s made out of a kind of frustration. There’s this kind of compression in it, and then it’s looking for a release.” At the end of To the Old World, after Leckey’s stupid bus stop kid has been turned into a repetitive motif, rendered in 3D, and re-enacted by an acrobat who recreates the jump from various angles, the piece ends in song – “a song of joy” as the boy disappears into the glint of fractured glass. Artistically, it’s a kind of ultimate release, but the ending also reflects another side of Leckey’s creative output – making music and hosting a monthly show on the Hackney-based online radio station, NTS. Does he find soundbites and music in the same way he finds footage? “There’s less choice with video,” Leckey says; he has a library of footage and sound, but the latter is much vaster. The problem with video is that, sometimes, it seems out of bounds, watermarked in a way that sound isn’t. But Leckey tried to approach To the Old World in the way he would making music or putting together an NTS show – music, with a visual element.

“I want to find a way of using video how I use sound, because it involves a sort of not caring, or not caring so much.”

When Leckey explains that his work is about getting to the root of what compels him about the footage and materials that he is drawn to, he jokingly asks why he “can’t just go out into a field and enjoy nature instead?” But, it seems, that is precisely what his next work will be. He is currently working on an accompaniment to the bus stop video which he summarises as a being “about a hermit getting joyful.” Leckey’s inspiration for this work comes from Orthodox Christian iconography – paintings of religious saints that don’t adhere to a traditional, Western understanding of art history. “These icons are not images or pictures,” Leckey says, but portals;

“When you look at an icon of a saint, you’re looking into heaven.”

So the artist has set about finding his own portal (or, a ‘channel as grace’ as the act of looking into heaven through an icon is called). “I went out to Ally Pally on a really beautiful, sunny day and recorded myself getting overwhelmed by the world.” The idea stemmed from the artist’s contemplation of hope, and hopelessness, during the pandemic – and a curiosity, then, to delve more into the divine. There’s a community of people that Leckey follows on Substack and TikTok who are investigating something similar. “Like I said before, the divine shows up at the trash stratum, and maybe it is.” The trash stratum here is TikTok, where users in Leckey’s orbit are attempting to grapple with what may lie beyond, or within, the internet (comparisons are made between the structure of the world wide web, and its similarities with NASA’s images of space). “There’s a strange confluence of things,” Leckey notes. “I’ve felt this for a while about technology – that it’s inducing this strange kind of medieval state, in the sense that they cohabited two realms between the spiritual and the profane. We sort of exist in two realms now. It’s the immaterial space, like you originally asked me about the internet, and the only antecedent I can think of is the medieval.” And with that, Leckey heads off to Sainsbury’s to get some bits.

Credits

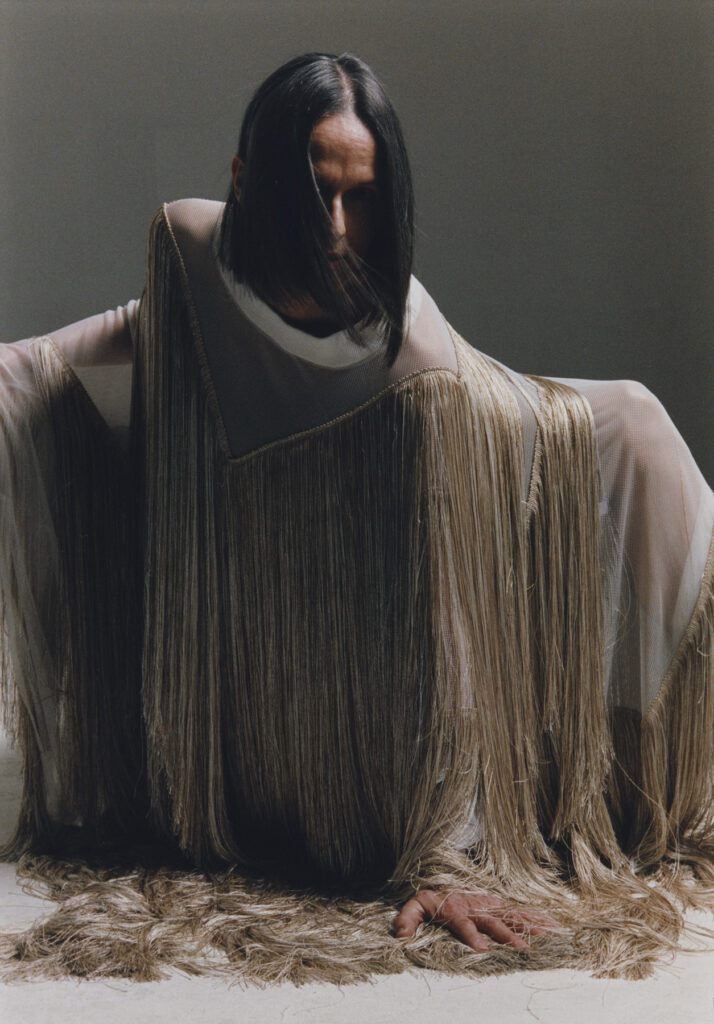

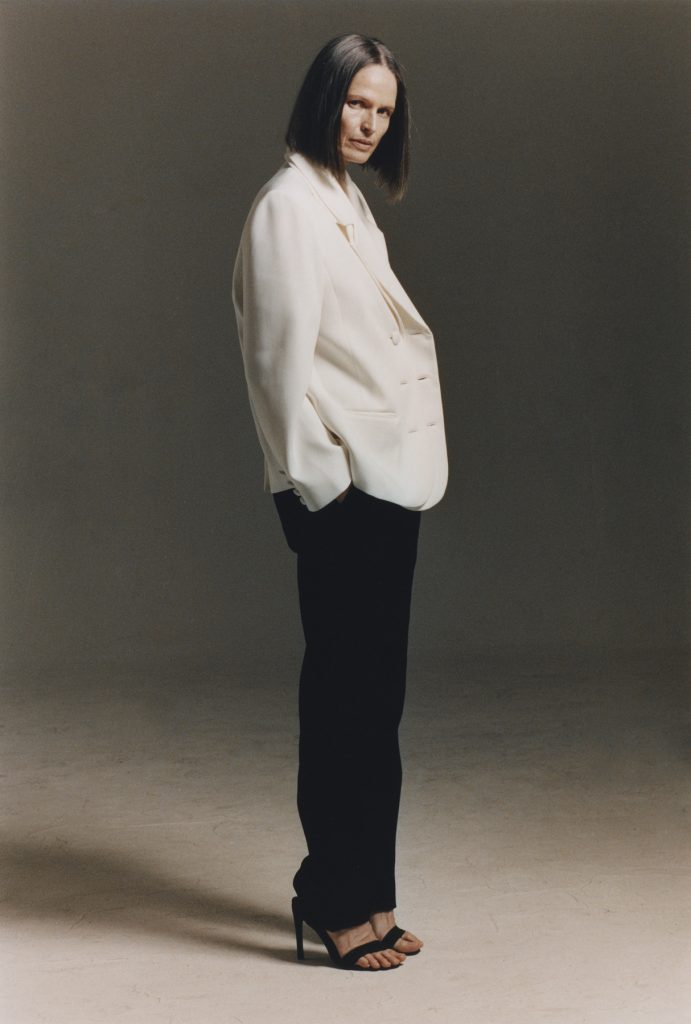

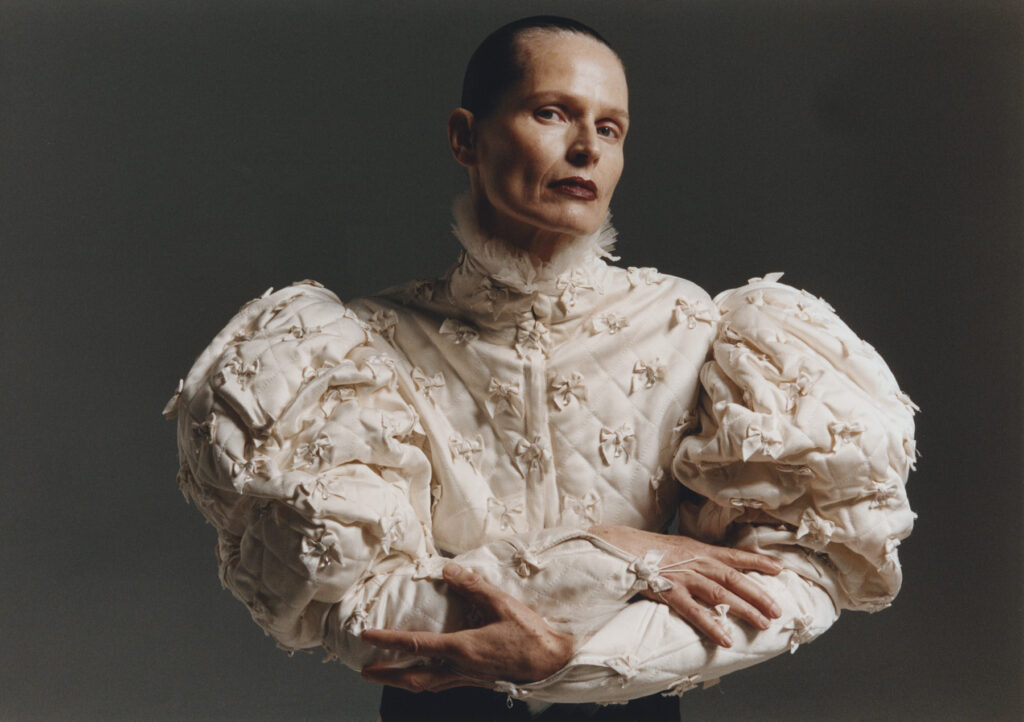

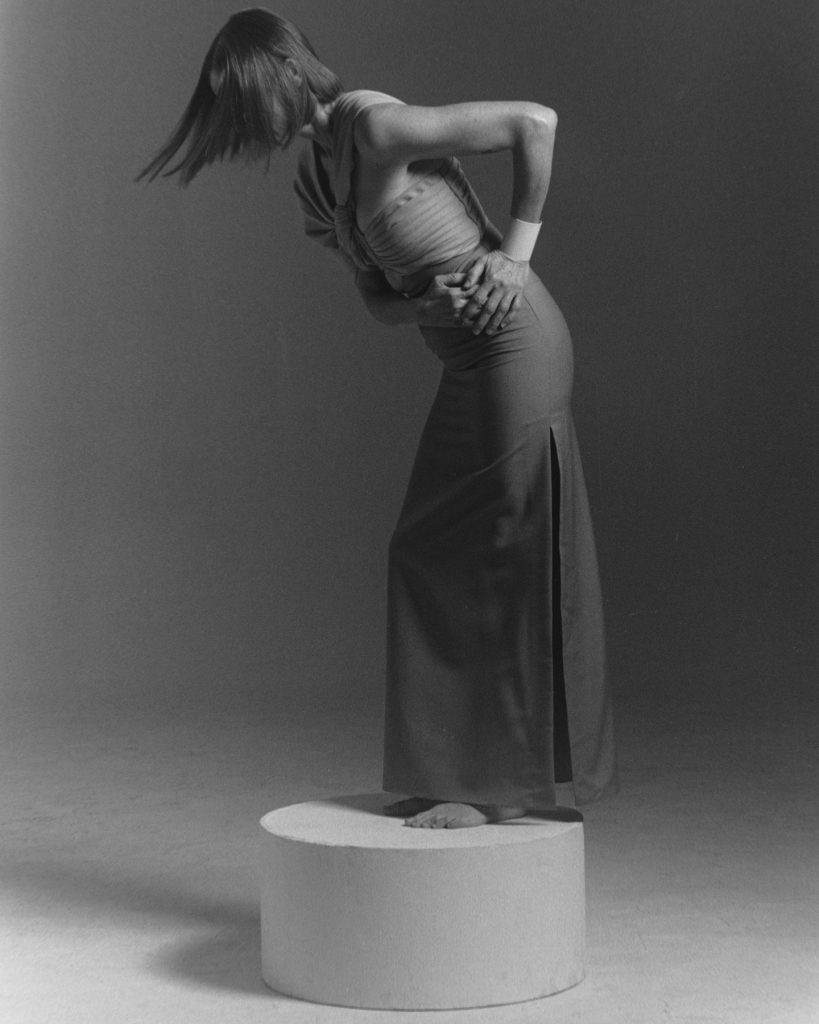

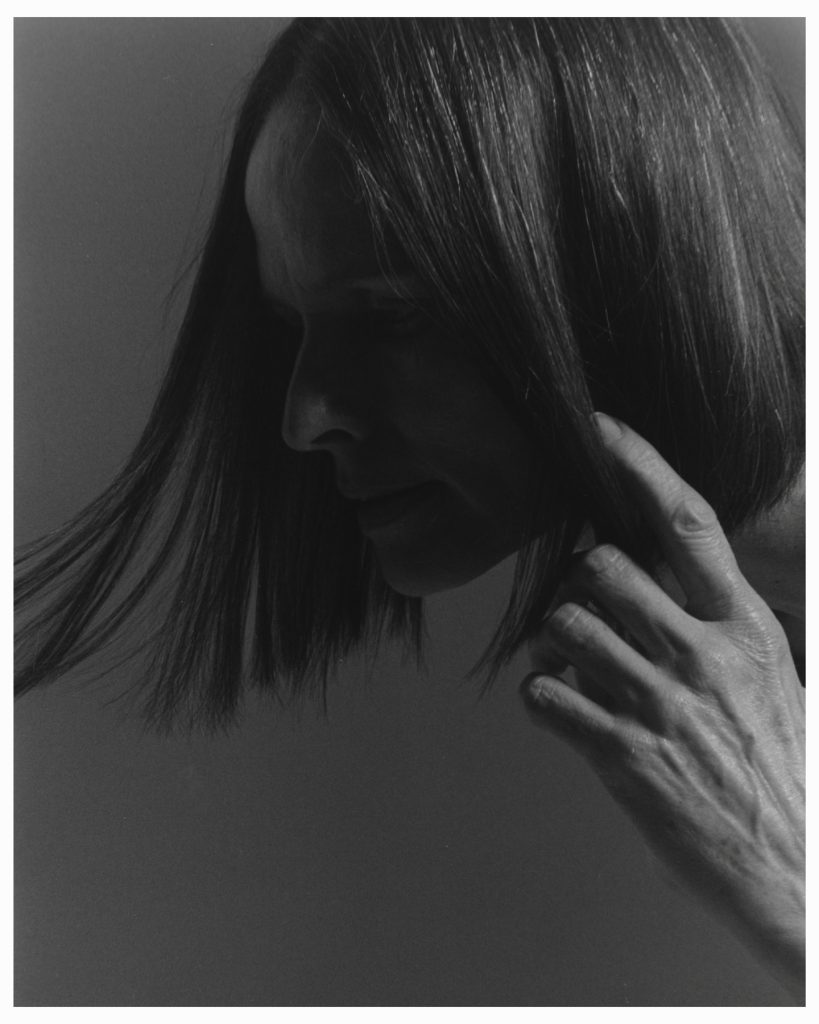

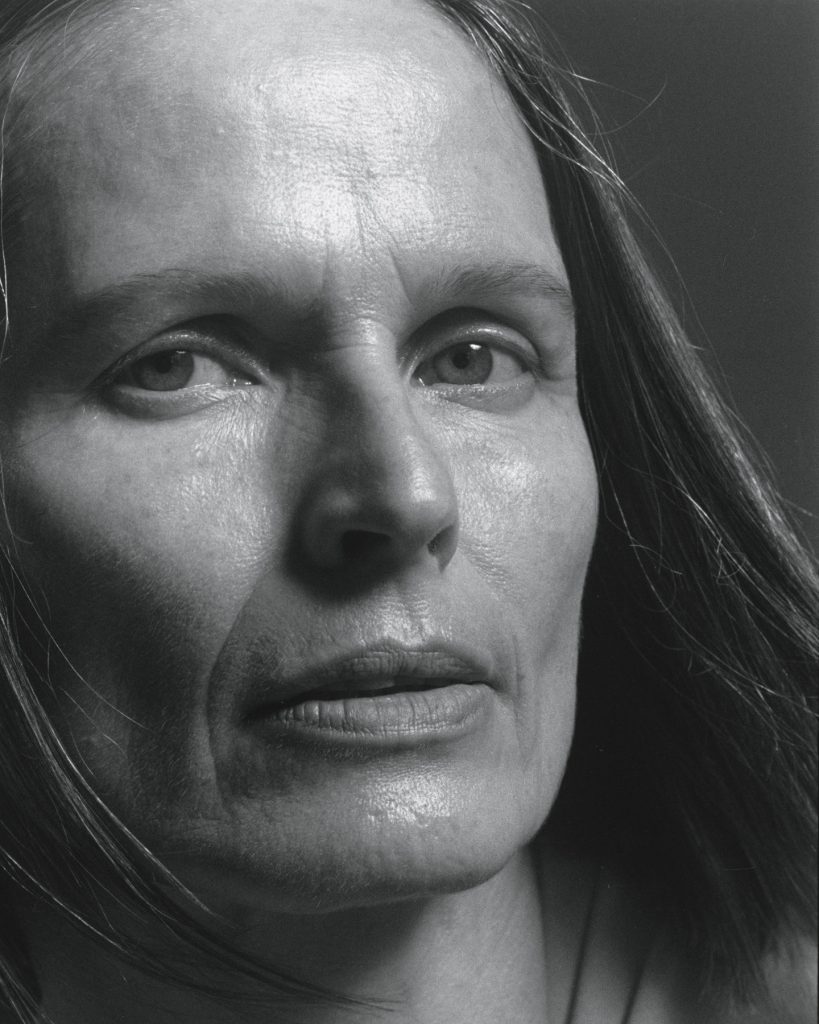

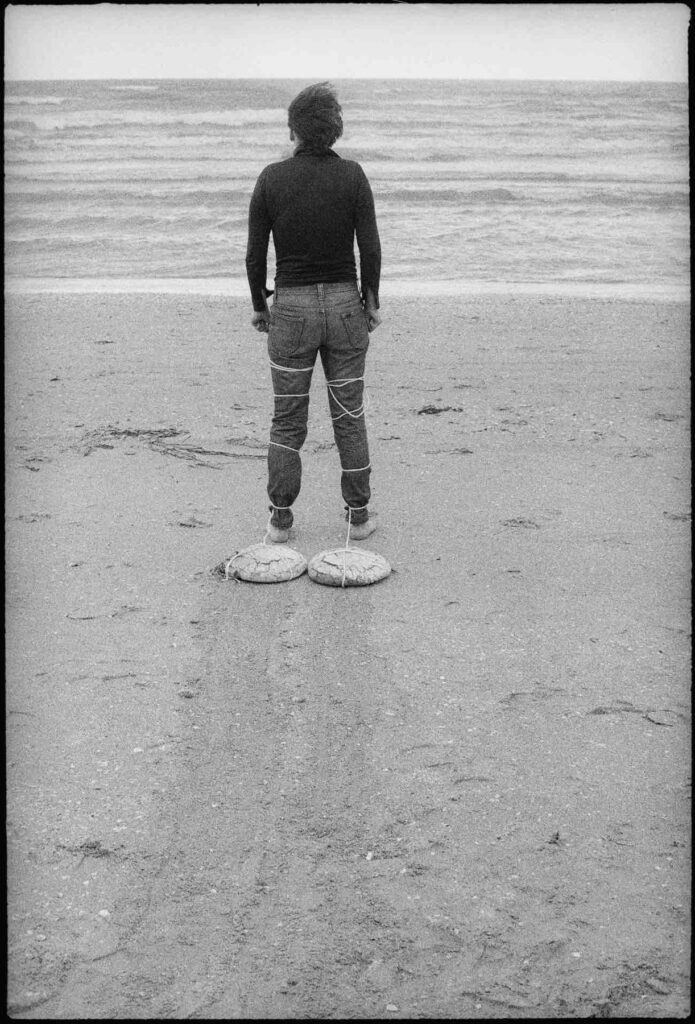

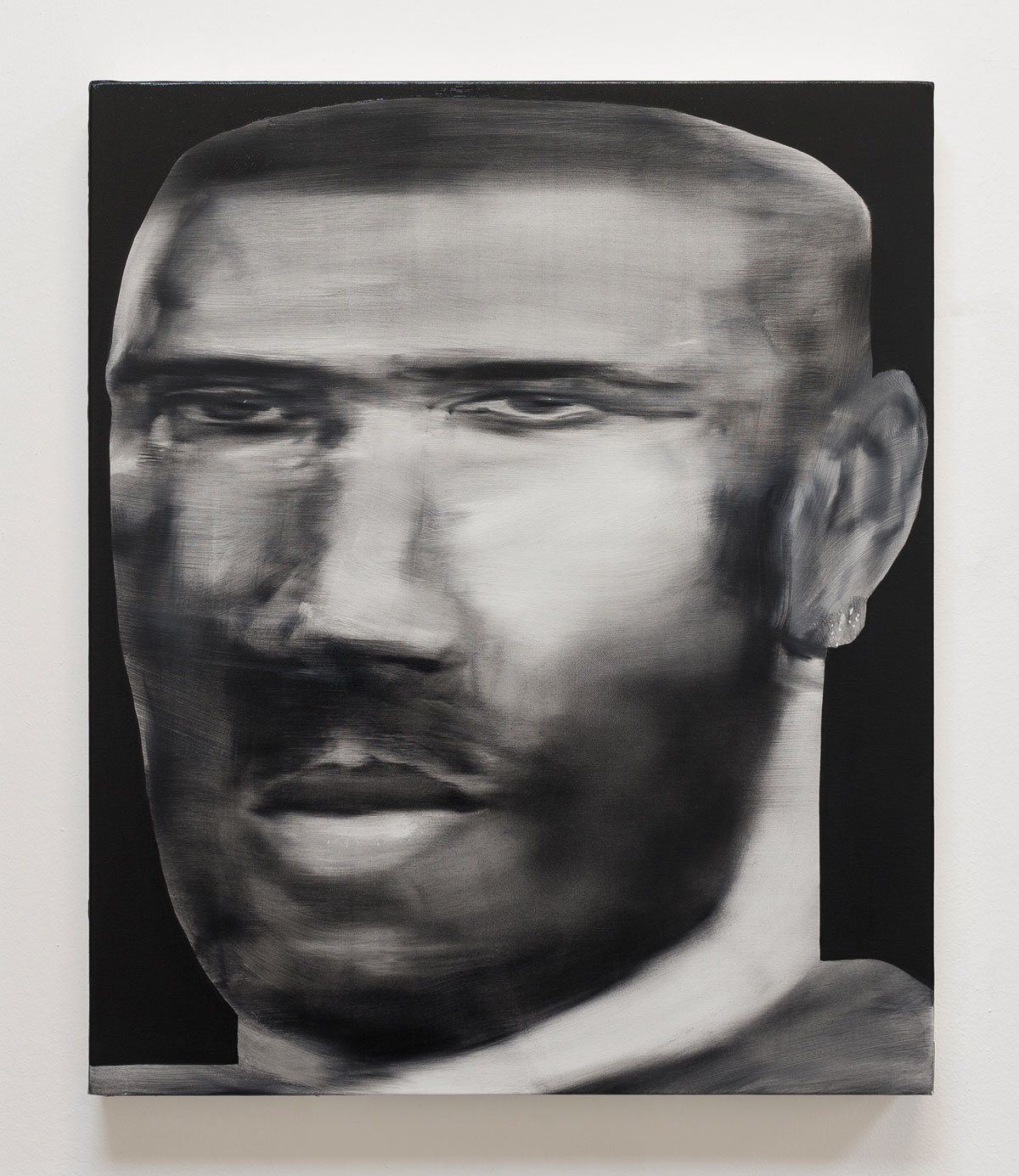

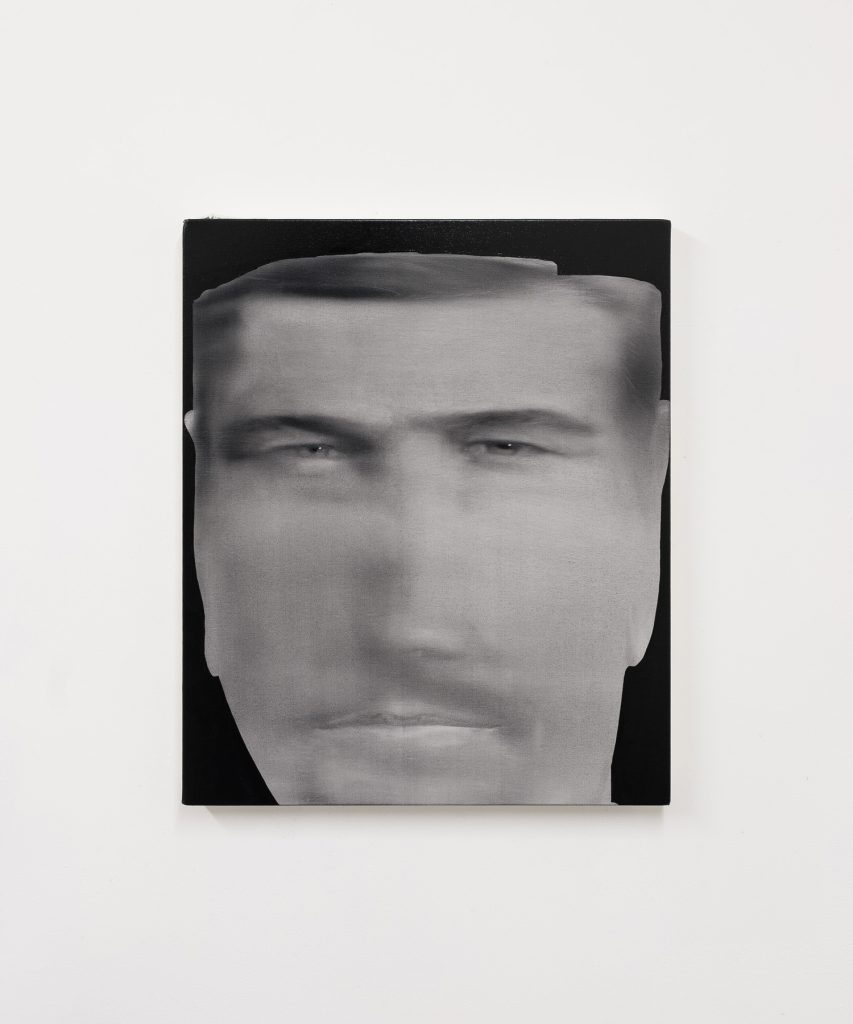

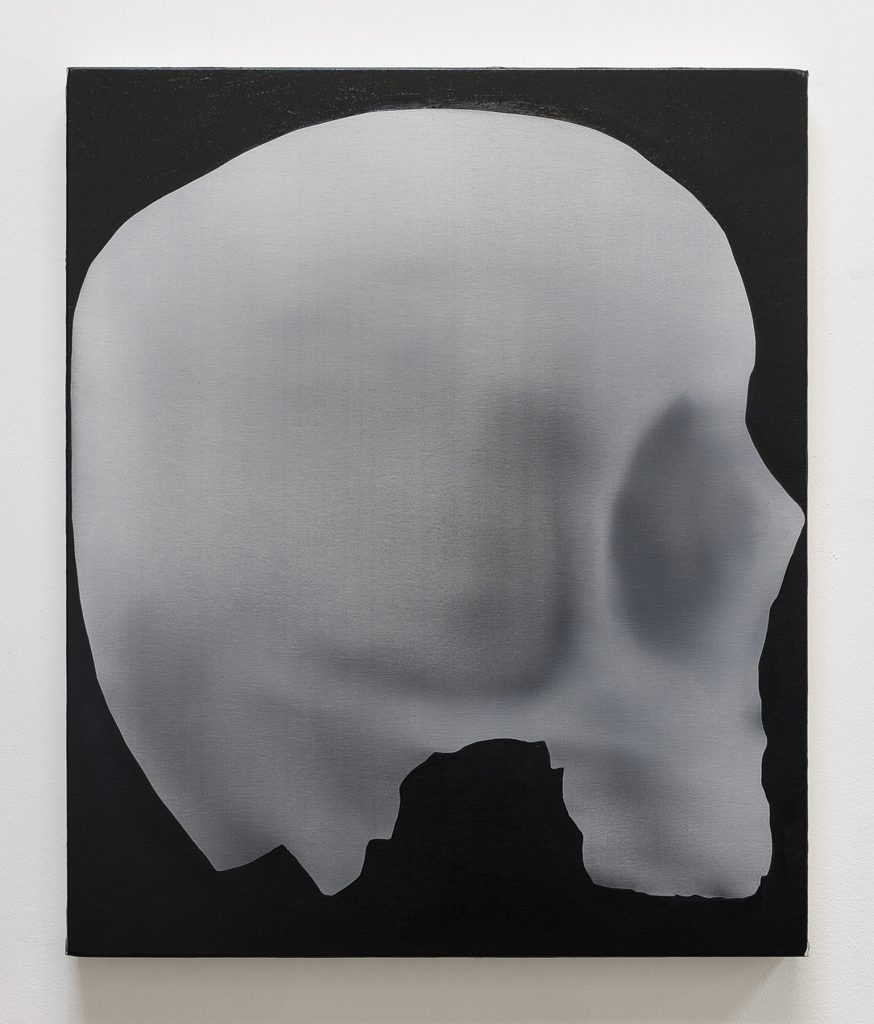

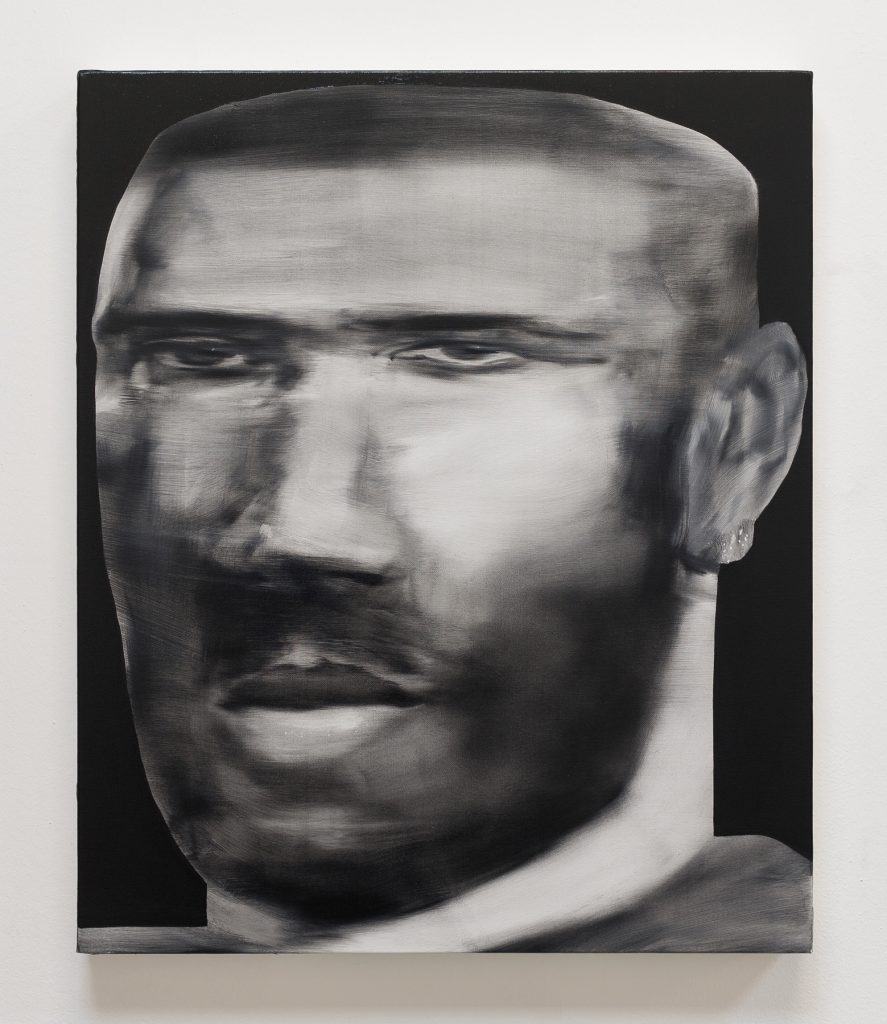

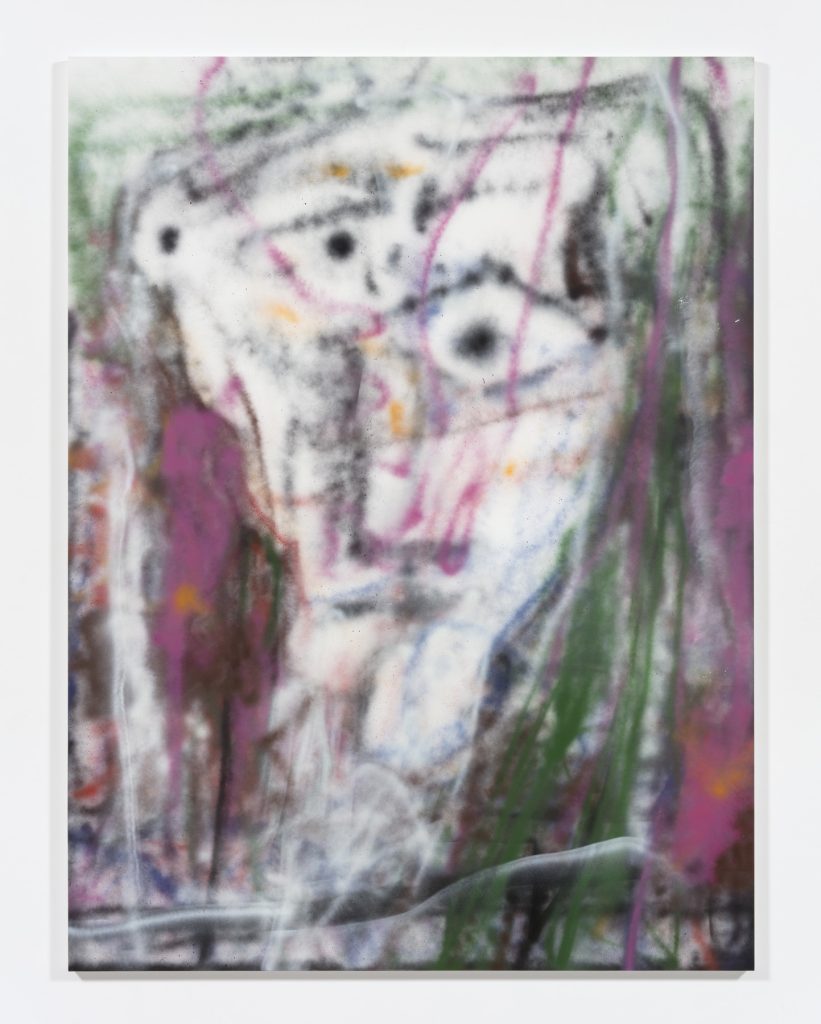

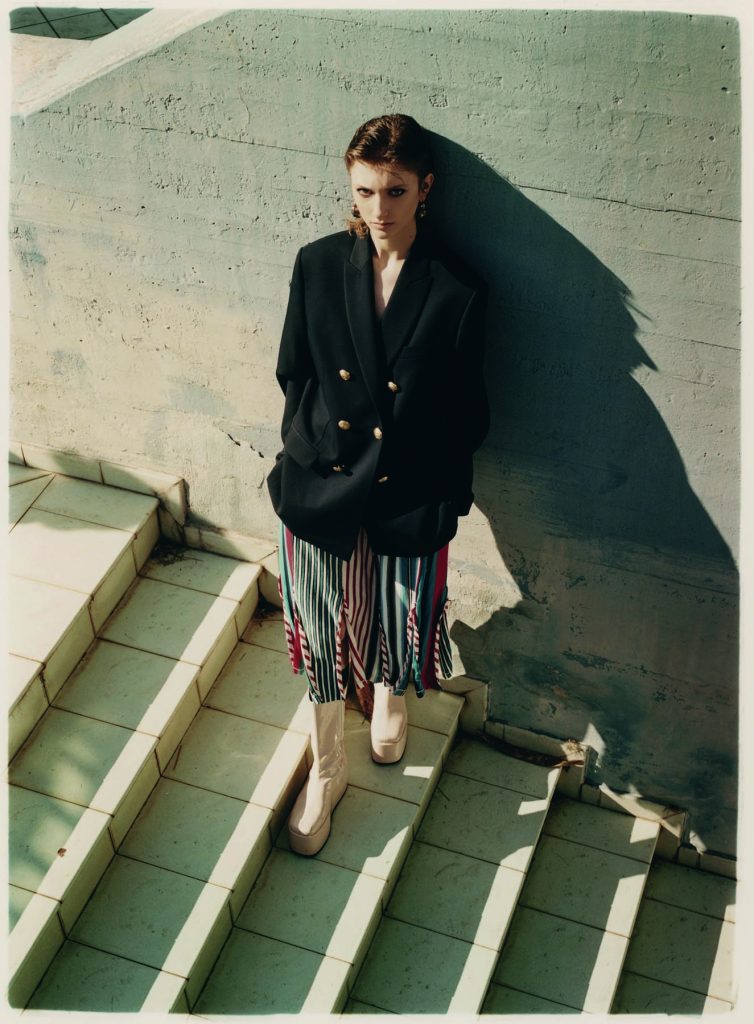

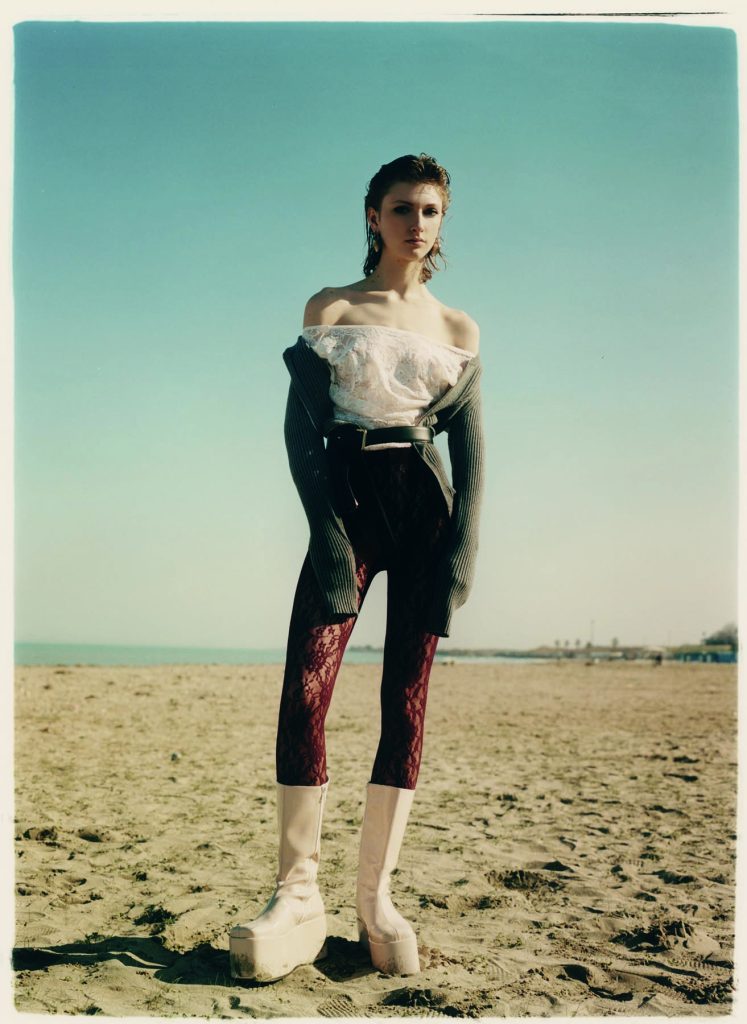

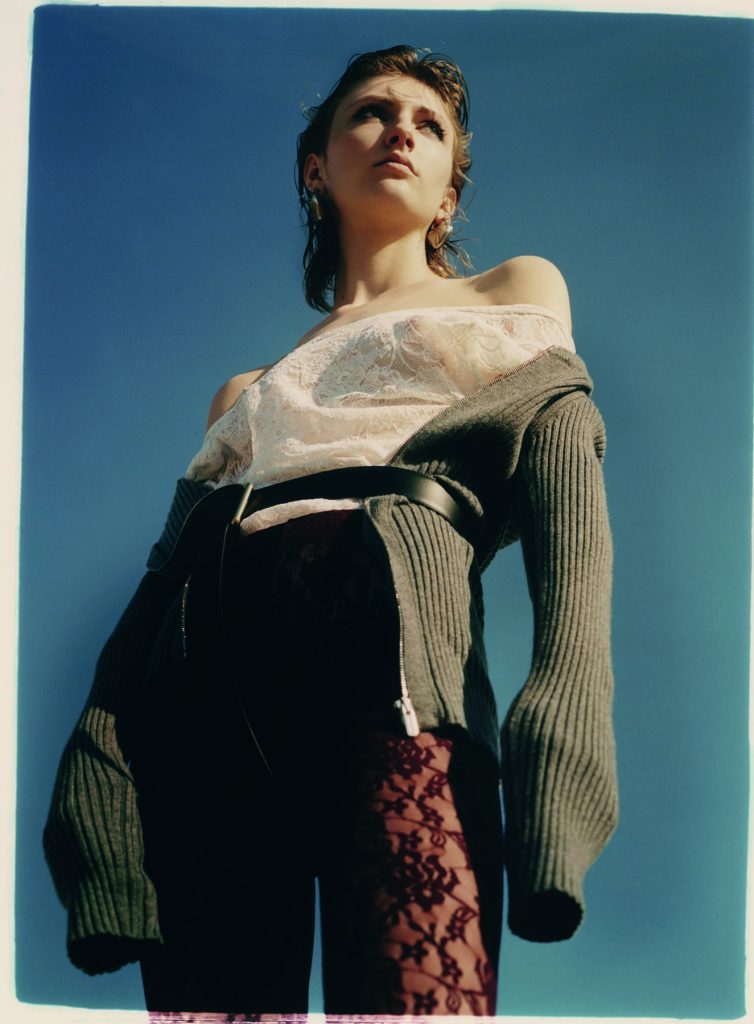

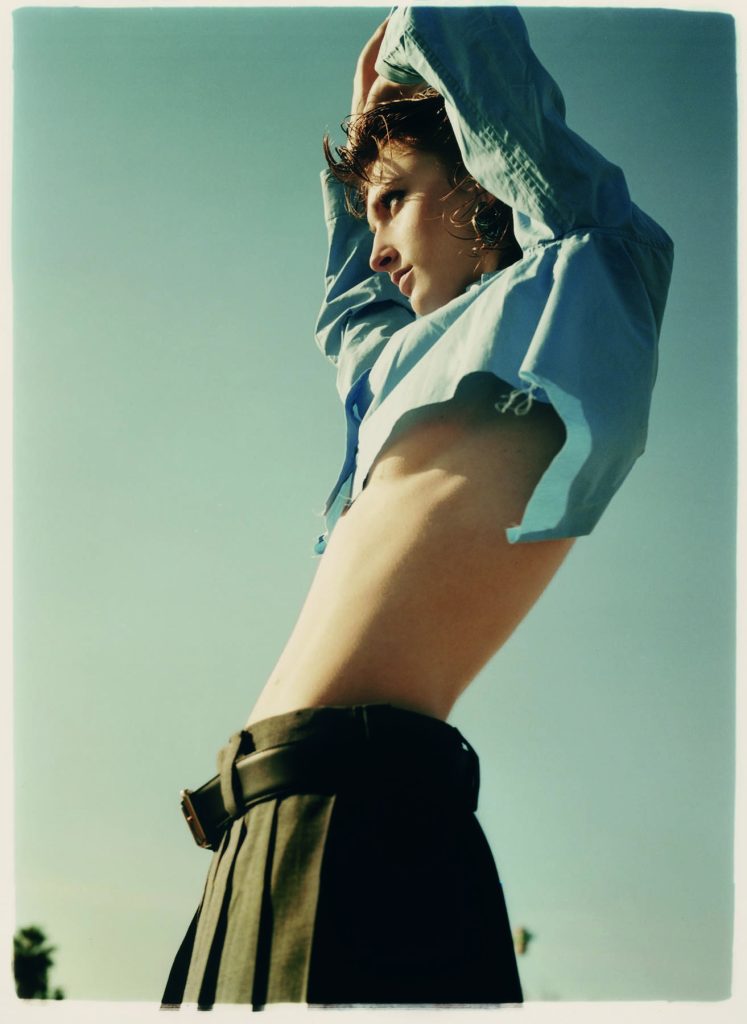

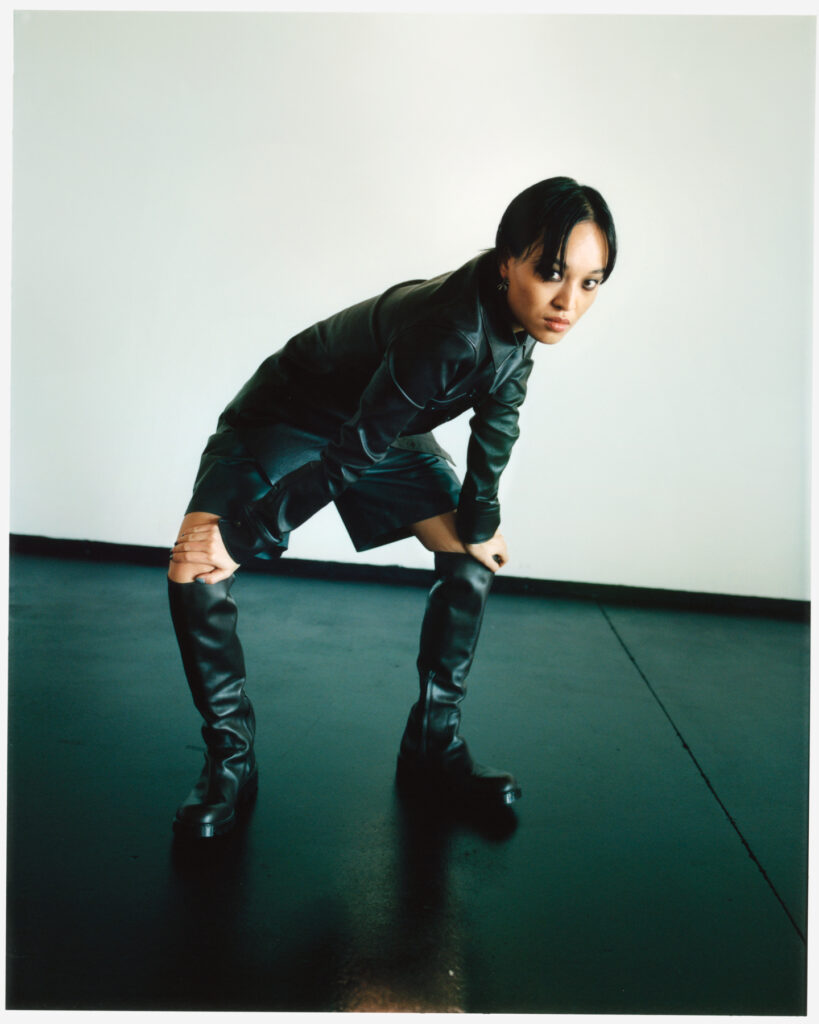

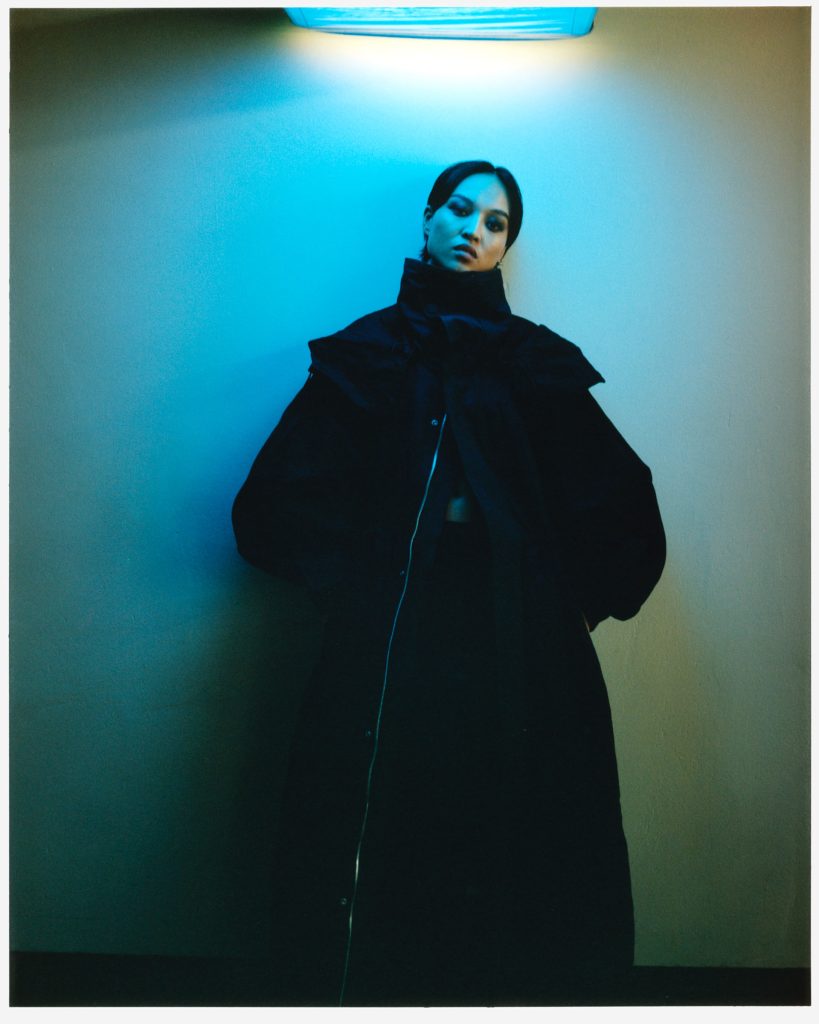

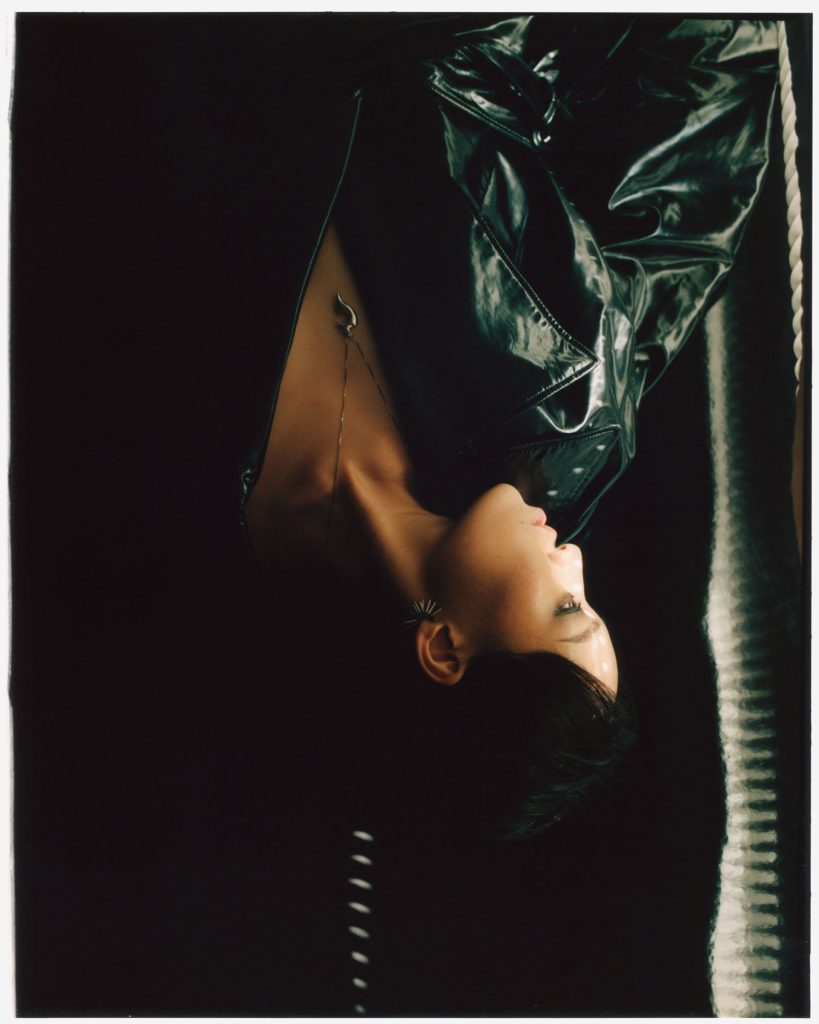

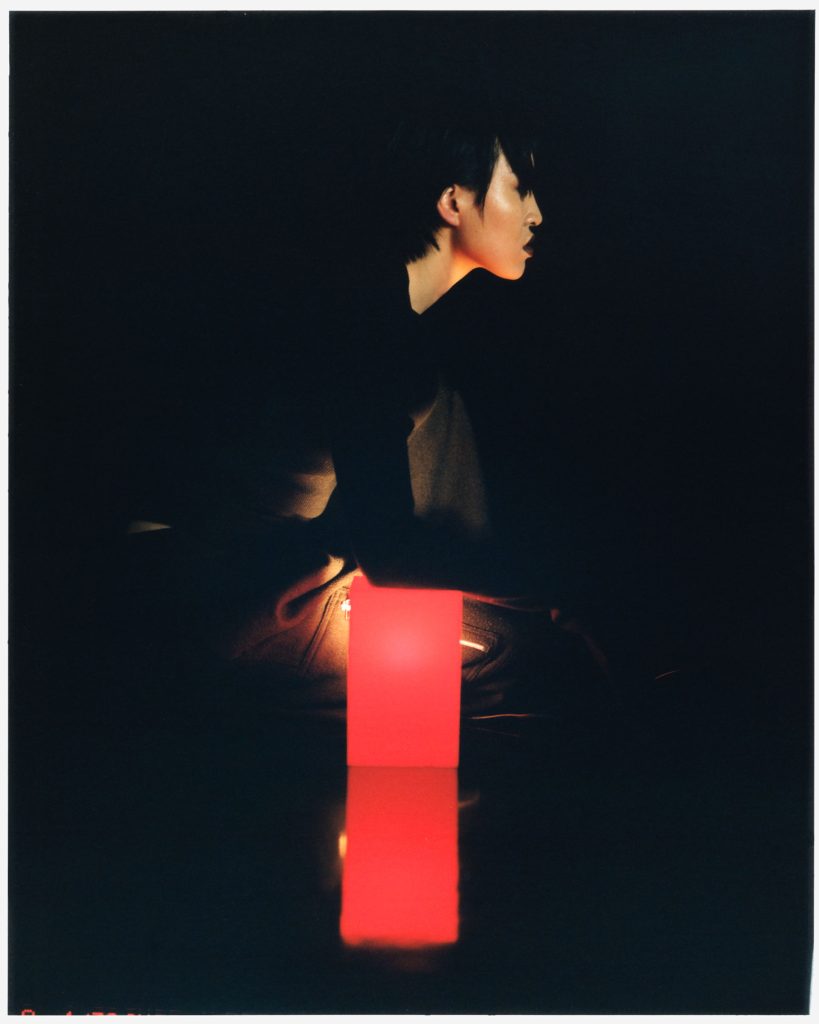

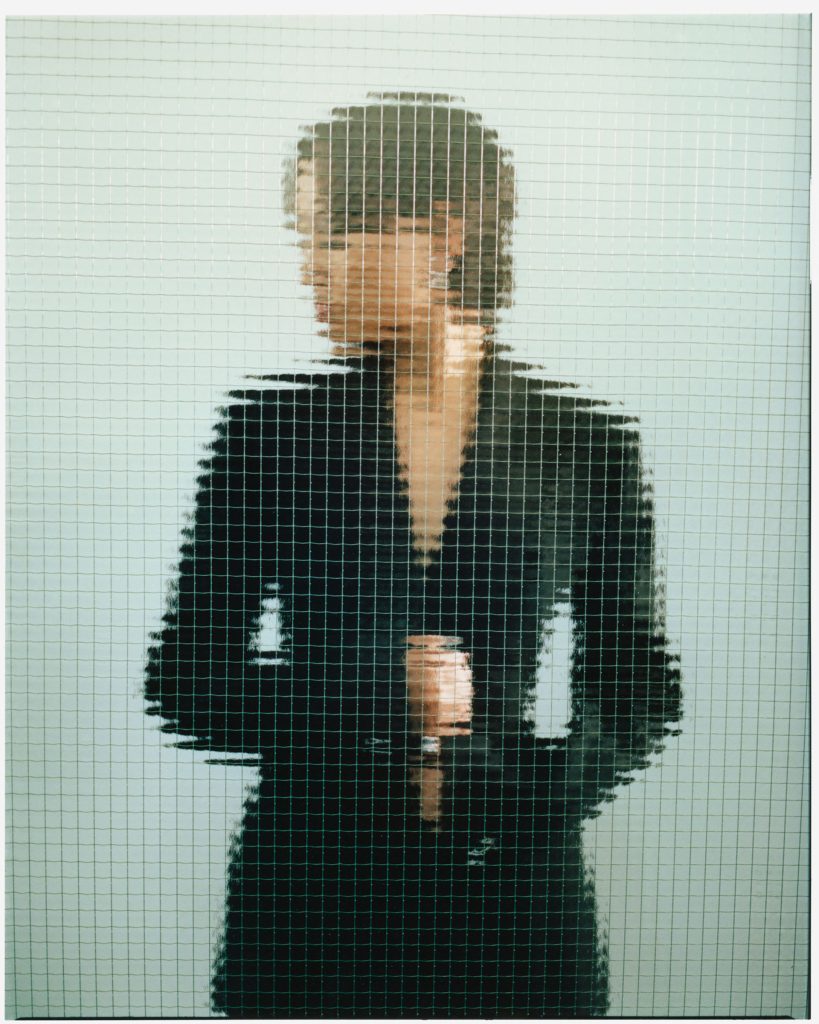

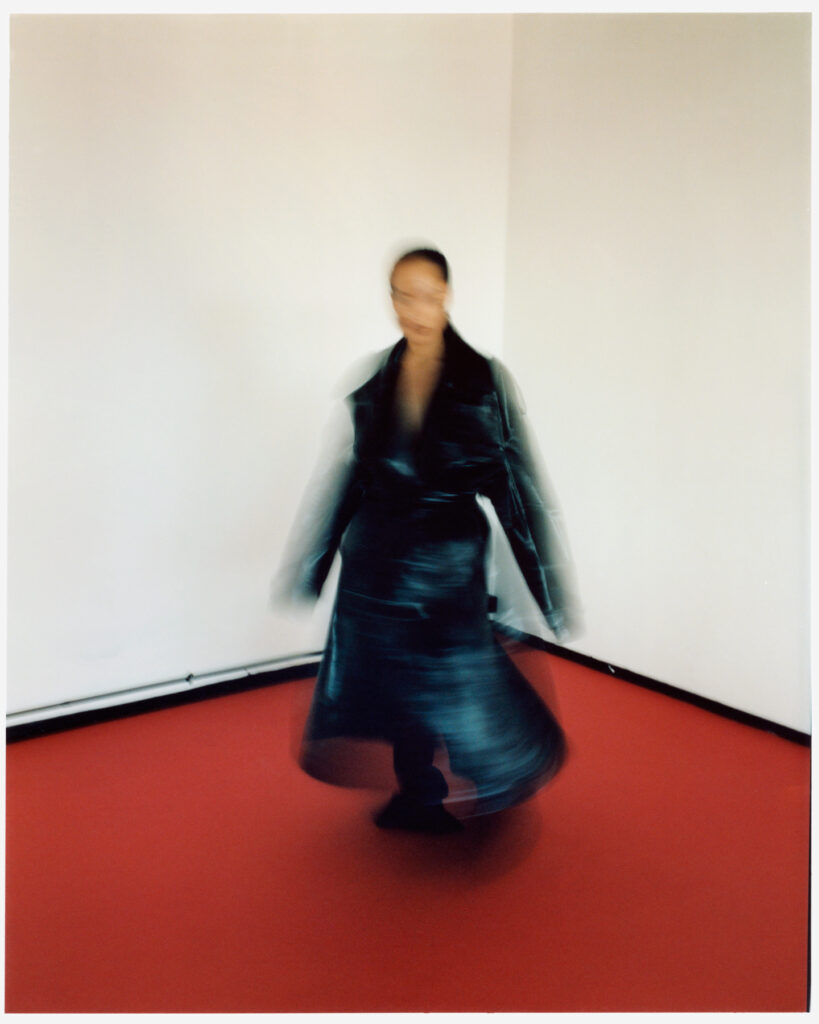

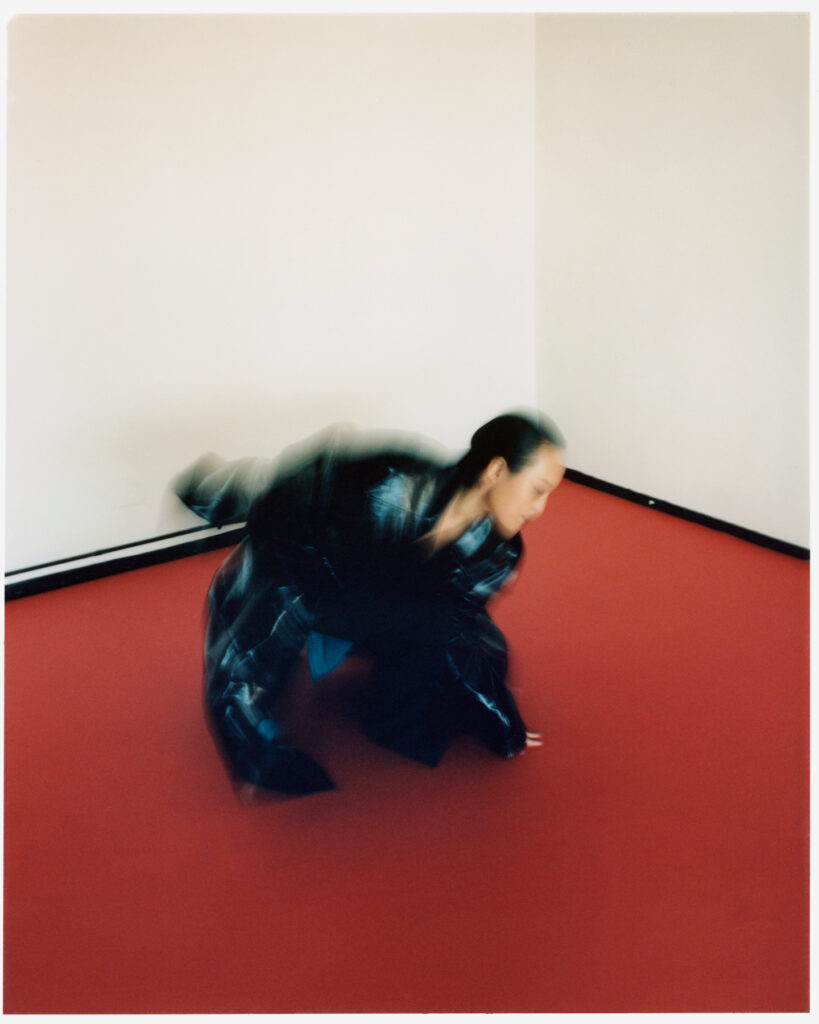

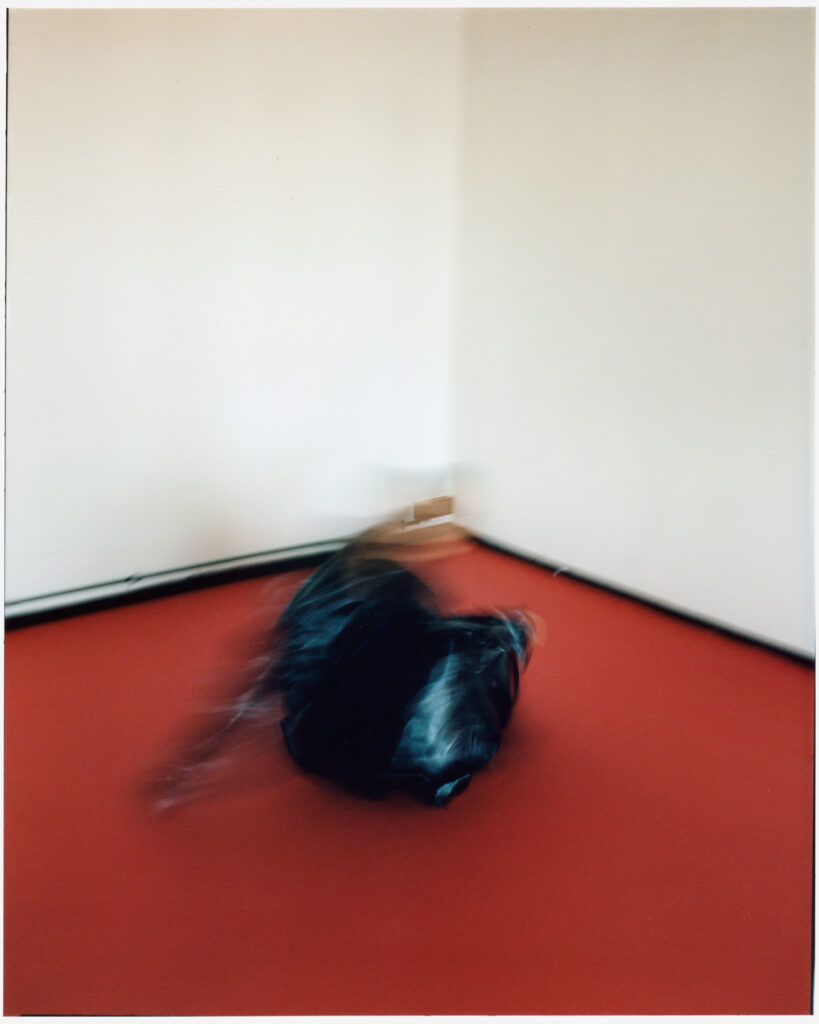

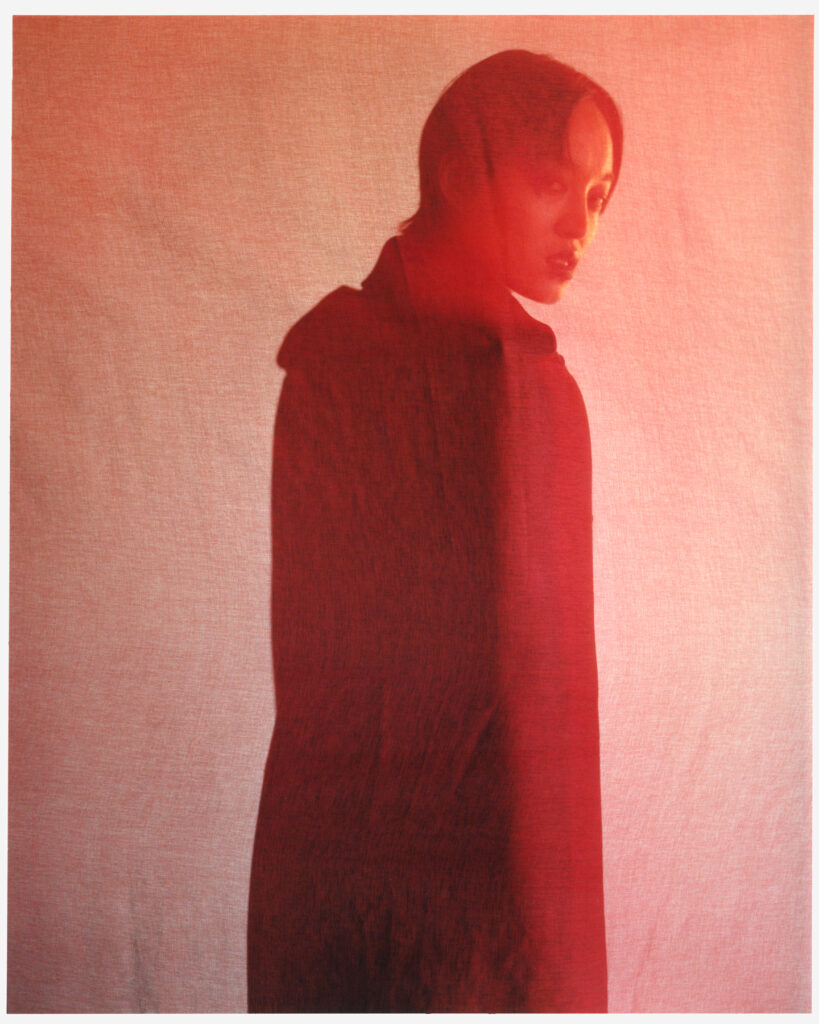

Images · Mark Leckey

https://markleckey.com/