Rules of Non-Engagement

Vanessa Beecroft (b.1969) discusses how her work serves as a form of therapy, exploring personal conflicts and universal issues within a group. Her exploration of body image and gender politics has influenced her perception of herself and society.

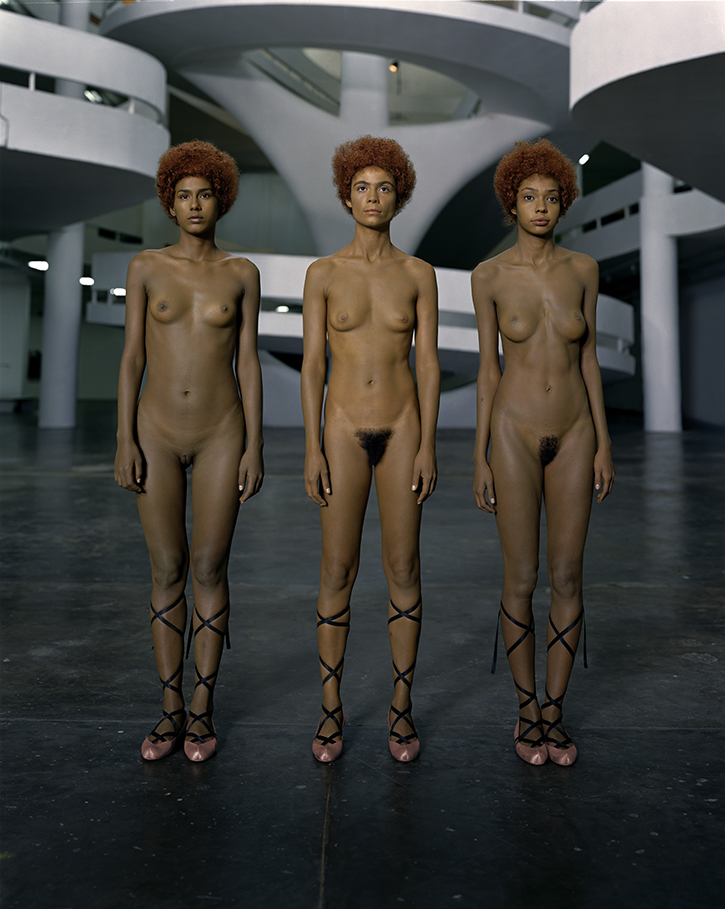

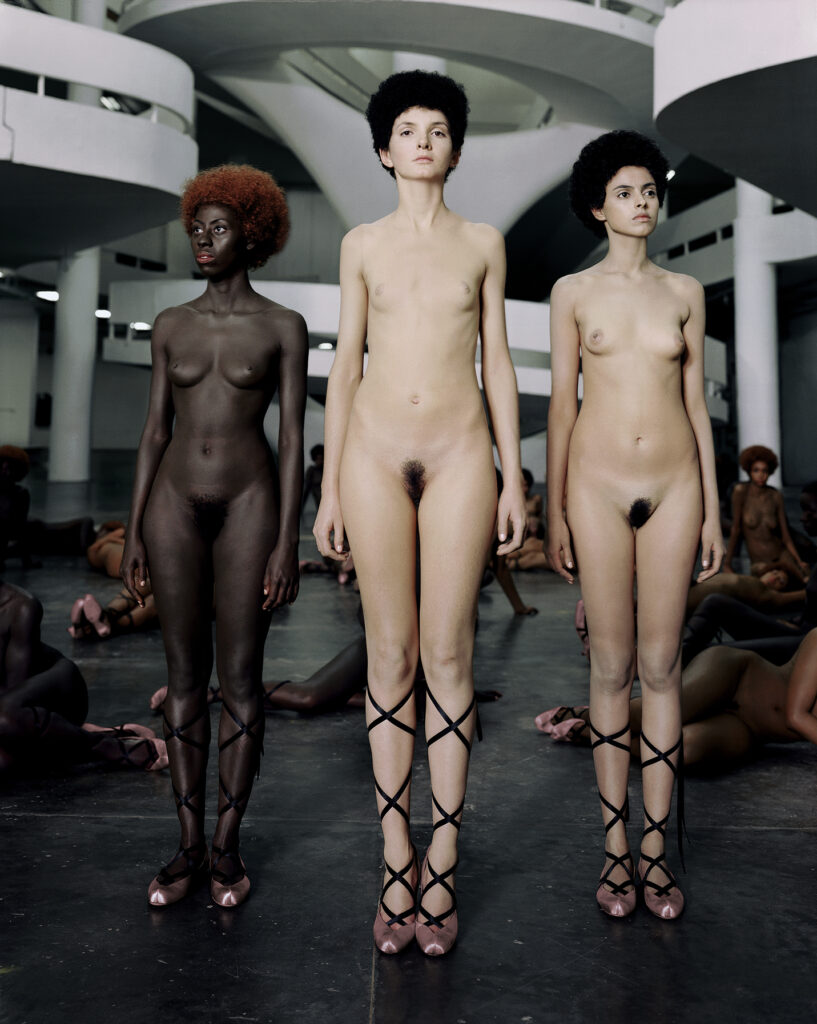

Her performances are known for their powerful portrayal of vulnerability and invulnerability, creating a unique interaction between the audience and the performers.The intentional discomfort provoked in her performances pushes boundaries and stimulates thought-provoking reactions.

This interview offers profound insights into Vanessa Beecroft’s artistic journey, delving into her personal investigation and its transformative impact on her life and art.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: Vanessa, throughout your career, your work has been deeply personal and introspective. Could you tell us about a specific work where personal investigation was particularly critical to its development?

Vanessa Beecroft: The way I work is to live my life like an artwork in all aspects. The hard part is life. Once that is addressed, work comes as a consequence.

A particularly challenging experience has been the project in South Sudan, which started as a personal venture and became an intricately tangled dilemma that compromised the stability of my own family. I traveled to South Sudan immediately after the war in 2005 in the attempt to shoot a documentary film on the presence of the Church and was invited by the bishop to the local orphanage where three newborns were unable to latch onto plastic bottles. I nursed them for two weeks and continued to return to South Sudan several times while in New York I was nursing my son Virgil. I developed a bond with the twin boys and wanted to adopt them, but in the end I was persuaded by my ex-husband that it wasn’t the best option for the children. I photographed myself breastfeeding the twins in an image that suggested a white Madonna with two baby black Jesus’s which became controversial. I was commenting on the new form of neocolonialism espoused by the Church, using myself as a symbol of white righteousness. The image was purposefully ambivalent—loving, maternal and confrontational.

Alexandre-Camille Removille:You often use performance art to express complex emotions and concepts. How do you prepare for these performances mentally and emotionally?

Vanessa Beecroft: I don’t prepare for the performance. I prepare by living a certain life, abstaining as much as possible from the mainstream, living my own version of a contemporary romantic life and always being alert. Many times, I am not prepared for a performance. I just hope that nothing tragic happens. Artistically, regardless of whether the audience is happy or not, I am never satisfied.

The models are given “Rules of Non-Engagement,” simple instructions to follow during the performance: do not talk, do not smile, do not move too fast, do not move too slow, wait until the end of the performance, you’re like a picture, your action reflects on the others… etc.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: What role does vulnerability play in your artistic process, and how does personal investigation tie into the therapeutic aspect of your work?

Vanessa Beecroft:Vulnerability is in dialectic with invulnerability. Two parties, the audience and the performers, are confronting each other in real time, for the duration of a few hours, without a rational awareness of what is going on or the nature of the confrontation. They are both vulnerable from different positions. The audience is vulnerable in the face of their taboos and the women are vulnerable to the audience’s gaze.

I think the models in my performances express personal issues and these personal issues become universalised by being multiplied by the many women in the groups. What was a particular instance becomes universal by extension to a larger group. I handle my personal conflicts and investigations by projecting them into a larger group of individuals more or less similar to me (at least at the beginning of the work, in the 90’s).

Alexandre-Camille Removille:Given that your work often revolves around body image and gender politics, how has your personal investigation of these themes affected your perception of yourself and society?

Vanessa Beecroft: I wasn’t fully aware of the themes of my work. I tried to approach my performances as a portrait of a large group of women, similar to how we painted the model in art school. While portraying this woman in the performance, many other traits emerged, mostly not formal, but emotional, social and political. That is when I started to push in that direction, regardless of how that would impact myself socially. Sometimes I went really far and got in trouble.

Alexandre-Camille Removille:In your experience, how has the art world responded to the type of personal investigation you portray in your work? Has there been any resistance or particularly impactful support?

Vanessa Beecroft: I felt as if art world abandoned me after the initial success. The other worlds embraced me, but I didn’t want to be embraced by them so I tried to use those platforms to further the themes that I couldn’t otherwise investigate. The art world may come back. I became desensitised to these ephemeral worlds that are fundamentally false. I believe in addressing the art world in a historical sense. I had fun pushing my visions, while being financially depleted by these facts.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: In many of your performances, you seem to be exploring issues related to identity and body politics. How have these performances been a means of exploring your own identity?

Vanessa Beecroft: They have been means of exploring my own identity by studying other cases and relativizing mine. Externalizing these issues through my performances perhaps avoids a true healing of the self, which recalls the acts of a saint martyr, which is a hero of mine since a young age (Joan d’Arc, Santa Lucia, Santa Barbara etc.)

Alexandre-Camille Removille:Your work is often characterized by a strong female presence. Can you talk about your intentions behind this focus?

Vanessa Beecroft: It is self-representation. A portrait. I couldn’t accurately depict anything other than a woman. By being a woman, I can push the subject further. Experimenting on myself first and the group second.

Alexandre-Camille Removille:There have been debates about your work from a feminist perspective, with some critics arguing that it reinforces harmful stereotypes of women. How do you respond to these critiques?

Vanessa Beecroft: By presenting a group of women naked in front of an audience I am not objectifying the women, I am showing the audience a group of naked women, which triggers them—their beliefs, self-perception, anger, prejudice, and more. The women are placed there for this reason and until they cease to provoke this reaction will continue to be exhibited. The fact that they’re exhibited as art makes them “intellectually safe,” like being on diplomatic ground.

Alexandre-Camille Removille:You’ve spent a significant part of your career in the United States. How do you navigate your dual sense of belonging to both Italian and American cultures in your work?

Vanessa Beecroft: I never felt as though I belonged somewhere since I was a child. I relocated to Italy when I had already learned English in London and from that point on, I felt displaced. So what I do is to assimilate the elements to which I feel closer in every culture. Italian language and artistic heritage, music, architecture, landscape. American contemporary spirit, ethnic diversity, power, politics. I absorb culture from other countries too. My work is where all of these elements converge.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: Have you ever felt any tension between your Italian roots and the global, often American-centric, art world? If so, how have you navigated this?

Vanessa Beecroft: I am probably considered an immigrant. I will never completely adapt to the new country as I don’t need to, and I like to be alien in all countries. The proliferation of my work is probably compromised by this, but I am not running a business. As long as the work itself is not compromised I am happy with the discrepancies.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: What learnings or insights have you gained from projects that didn’t materialise as planned?

Vanessa Beecroft: Many projects didn’t materialise as I’d hoped. The learning is that certain topics are untouchable politically and that the wider world is one. And it is all connected and self-sustaining.

Alexandre-Camille Removille:How do you decide whether to persevere with a difficult project or to let it go? Are there specific factors or considerations that guide this decision?

Vanessa Beecroft: If I decide that a project is worth pursuing, I will continue until it is completed. Unfortunately the project sometimes gets artistically weakened by complications and adversities.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: What role does your family play in your creative process? Do they influence your work in any direct or indirect ways?

Vanessa Beecroft: As they participate in my life, they influence the work too. They humanize me and therefore indirectly affect my perception of the world, of other human beings and my life experience. My son Dean, for example, helps me in the creation of music and photography, I photographed my daughter and in general I created a large photo album of them which isn’t public.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: Many of your performances are known to provoke discomfort in the viewer. How intentional is this in your work? What do you hope the audience gains or learns from this discomfort?

Vanessa Beecroft: Initially I sought to apply the Brechtian idea of staging the drama, giving clues to the audience from which they might come to their own ideal conclusion or synthesis. As the audience resisted, I started pushing harder. Developing concepts to provoke a reaction. Making them graphic. I could only present the problems with paint or mise-en-scène. I thought the audience to be educated and righteous. I didn’t think the art audience needed to learn anything, but they did. I want the audience to go home touched and to think about what they saw as if it was real.

Alexandre-Camille Removille: Vanessa, looking back over your career so far, what impact do you hope your work has had?

Vanessa Beecroft: It is almost like a dream. Today I see the world I was dreaming of as a child, visualised. Many ideas and images I had in my mind are now current. Aesthetics mostly, but also fashion and images of women, colors, patterns. Many times they appear differently to how I envisaged them, but now they exist so that I can move forwards towards new dreams.