SEAGULLS

NR presents Soundsights, Track Etymology’s sister column: An inquiry into the convergence between sound, its visual expressions, investigating music’s intrinsically visual narrative quality.

I wanted to start by delving a bit into the past. As I was researching your work, I found myself amidst an incredible journey down memory lane when I realized you were part of Aucan! I was 14 when Black Rainbow came out, and I remember that record being one the first passages I encountered toward two things: the more experimental side of electronic music and the world of music writing – online reviews, music theory, blogging. It was when I started to be conscious that a discourse around music existed, one beyond “simply” listening to it. At what point in your career did you decide to move towards different mediums, or rather, why did you feel the need to build upon music and annex to it a different, transdisciplinary narrative and experiential dimension?

Haha! I’m glad to hear you listened to Black Rainbow! Aucan was a seminal experience for me – we really shared everything for many years, and developed something which transcended the individual level. After nearly 10 years and over 300 live shows and we finally took a pause, I felt the need to find a place where I could converge various priorities. I studied philosophy, and then arts & design. During that time and along with friends, I co-founded what would become Krisis Publishing. I realized that to discover a new and authentic language, I needed to integrate the diverse, often conflicting, elements I was engaged with. Adopting a multidisciplinary approach to the project thus came naturally.

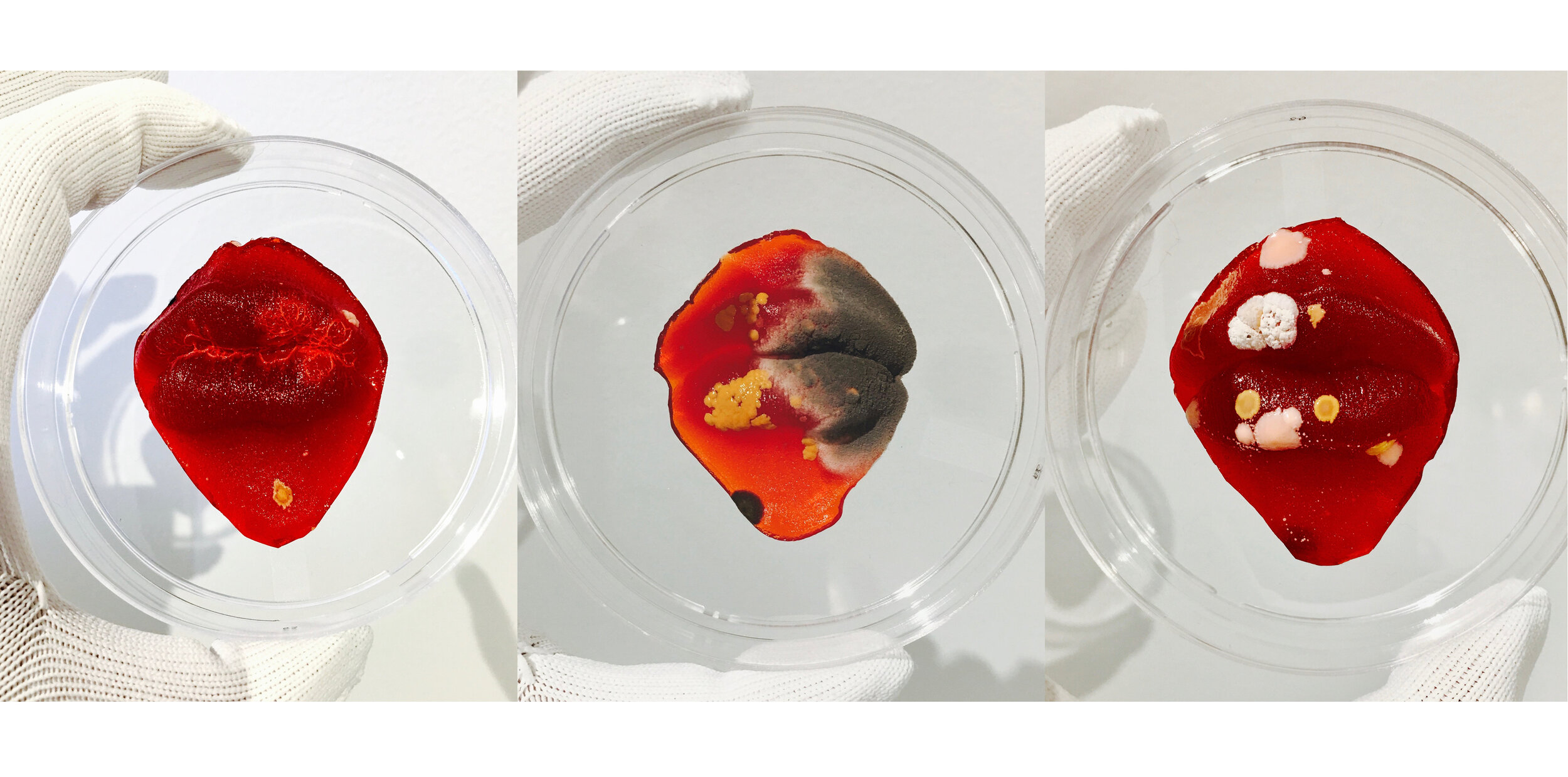

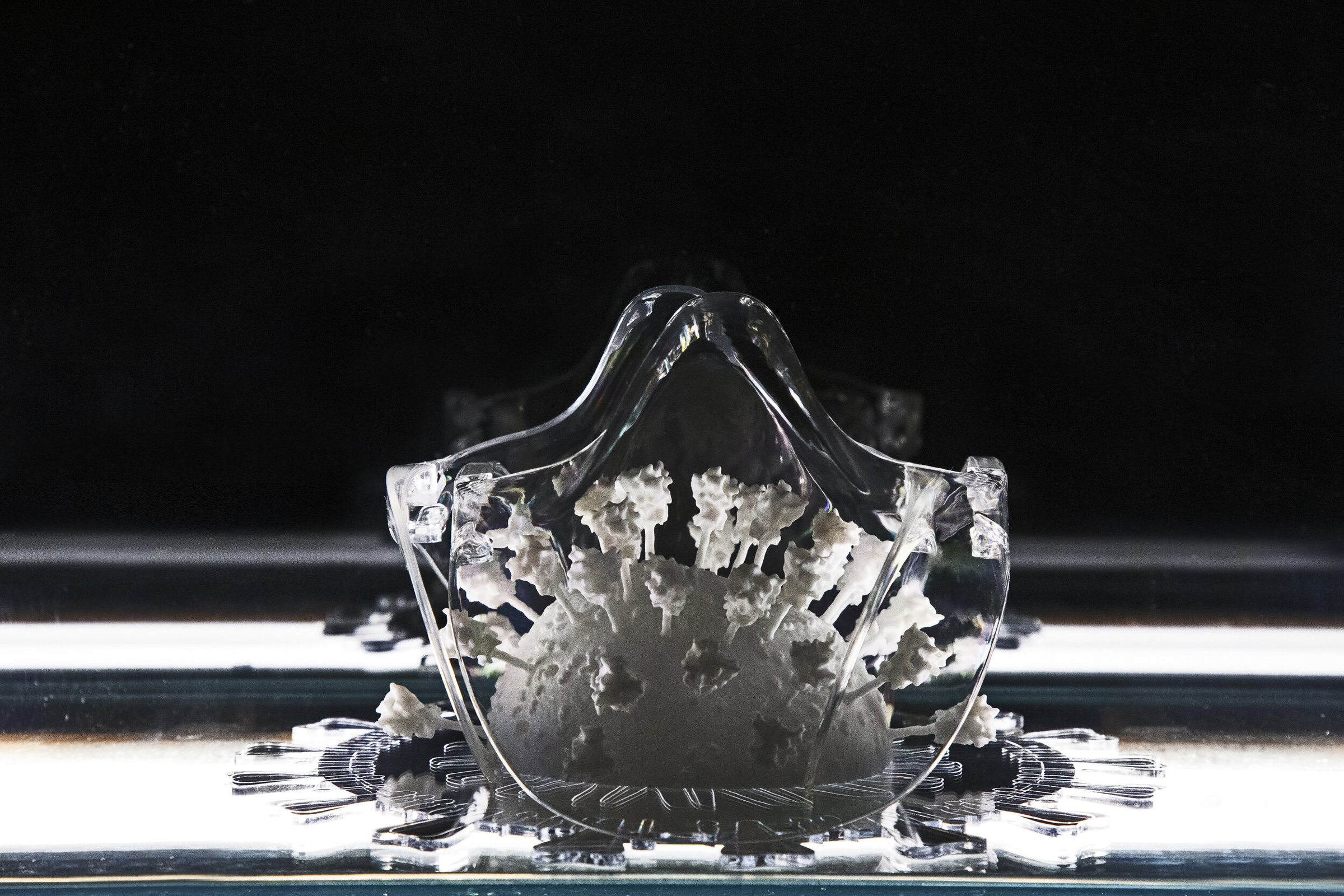

The pandemic, in a way, further propelled me in this direction. Until then, following Adversarial Feelings (2019), LOREM was predominantly a sonic project. However, the inability to tour for live shows forced me to explore new expressive avenues. I started producing AV live sessions in the studio designed for home viewing, aimed at audiences to experience them as they would a Netflix series—this format seemed most fitting given our confined livelihoods at the time. This shift led me closer to what is now the project’s narrative aspects, which today remains one of my primary interests. It was during this period that I conceived the idea to create several installations, such as the first iteration of Distrust Everything, which I introduced at Graz’s Elevate Festival in 2021.

“The limits of my language mean the limit of my world.” The opener of Wittgenstein tractatus that rings exceptionally true for AI and language models. Musical language and computational language have long been intertwined in LOREM production, and, as your press release states, Time Coils is “imbued with global cultural correspondence and reimagined connections sourced from a wide range of references.” I don’t want to spoil the fun of discovery, but I’m curious to hear from you about some of the influences and central elements behind this project and how they concurred to form its language/world.

The relationship between language and our experience of the world is indeed one of the fundamental aspects I aim to explore with LOREM. Significant influences for Time Coils, as well as for my practice, come from authors like Franco Bifo Berardi, Federico Campagna, Jacques Derrida and Timothy Morton, among others. Today, machine learning provides advanced statistical tools for working on data corpora (texts, images, videos) from an inter linguistic perspective:

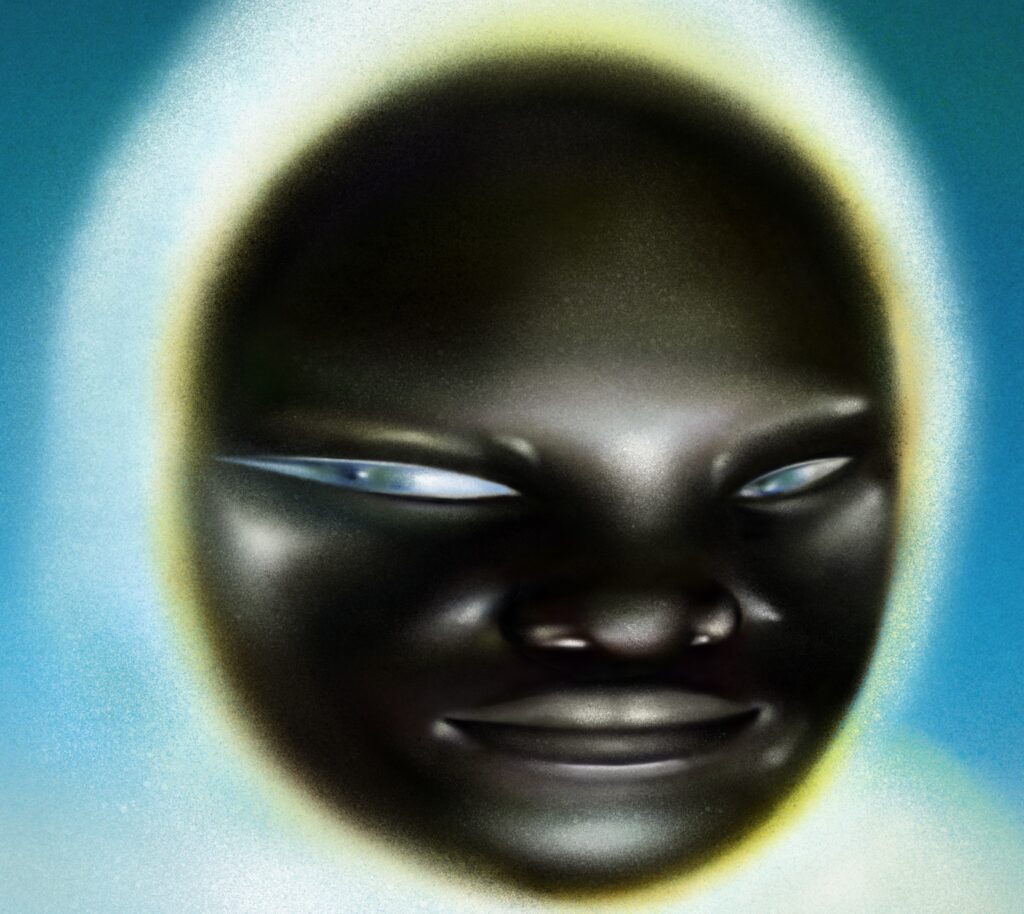

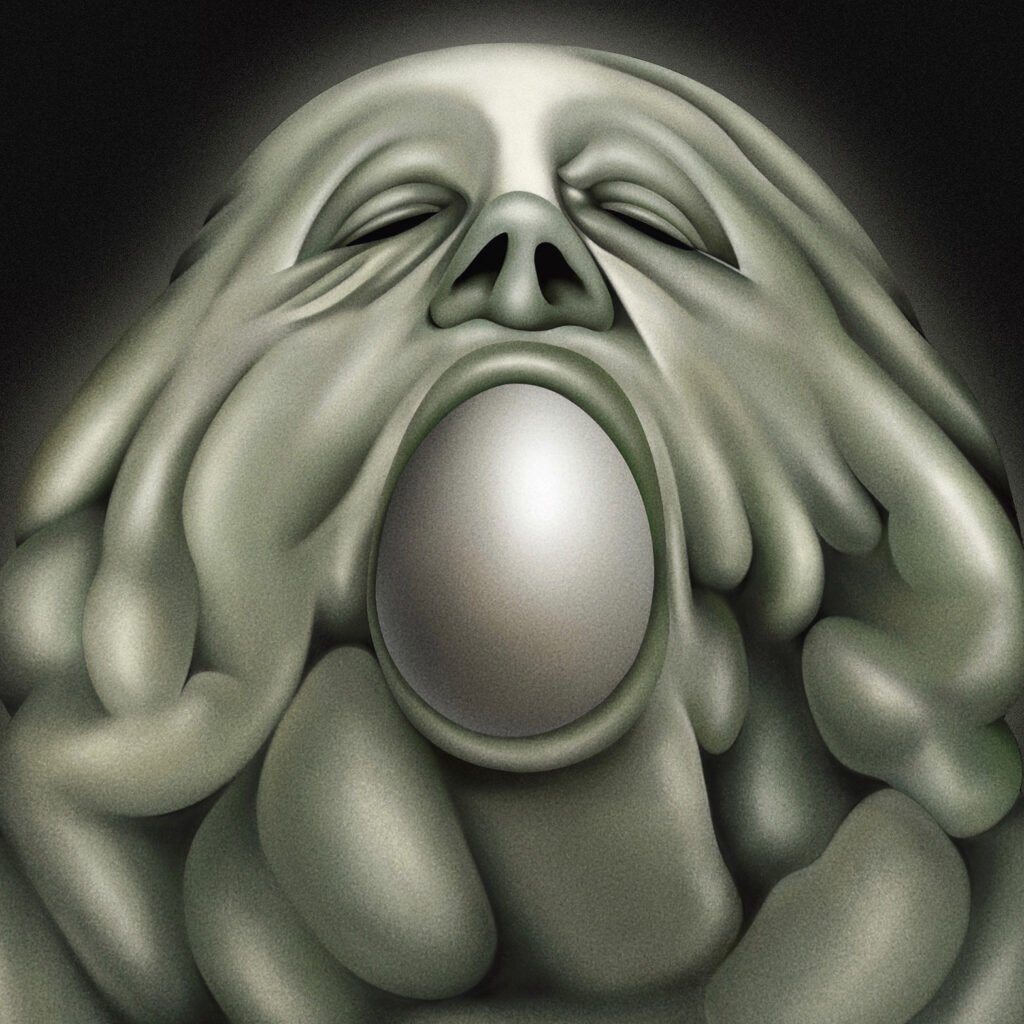

“I am interested in building archives of samples (and texts), and interpolating them to examine the interstices… to hear a hybrid sound between a voice and a guitar, to see a face that is also a tree, to read a text that lies between Thomas Pynchon and Franz Kafka.”

This approach was actually the starting point for writing Time Coils. I employed this method both on my samples and on those collected from a wide range of sources. The datasets include traces of soundtracks from early Walt Disney films, old school dubstep tracks, re-synthesized rap acapellas, and Italian prog music. Often the references are completely unrecognizable and become something else, but I like the idea that an attentive listener might discover traces of other works in a completely new form.

Did you have more of a narrative-oriented approach to the record or were you more interested in atmospheres and leaving sonic and visual traces for the listener to follow?

While the narrative dimension has become essential for LOREM, with Time Coils I felt compelled to refocus on purely musical exploration. Working with images and especially texts means that the music must always complement the overall experience. This requirement doesn’t weaken the music per se, but it does confine it within a specific framework. Over the last couple of years, I’ve attempted to differentiate my compositional approach depending on the consumption context. On one side, I am keen on advancing an inquiry into states of consciousness through texts and large-scale audiovisual narratives and installations. On the other, I’ve chosen to pursue a strictly musical path with my audio releases.

“Time Coils, therefore, departs from the concept of crafting a narrative and is instead an opportunity to create a sonic landscape, a sort of auditory swamp that results from a continuous process of self-digestion.”

Back on the AI Language-music adjacency, how do the two processes intertwine in your approach to composition? What do you think composing an algorithm and composing sounds have in common?

I would say that in this case, algorithmic writing is a part of the musical writing project. Perhaps for a “classic” programmer (or should I say a “real” programmer), the code is the true product of creative intervention. In my case, however, the output of the algorithmic processes is never the end result. Ultimately, it’s always me who picks up the pieces, trying to fit them together organically, sometimes without hiding the flaws.

Over the past few years, I’ve been developing methods to integrate machine learning into my musical production processes. These involve sampling, time-stretching, granular synthesis, and recorded instrumental music. I started in 2016 by using simple LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) systems to generate percussive MIDI files, which reinterpreted beats from my jam session recordings. Later, I began recording the automation I applied on samplers via SysEx to create datasets that would help train other models. Recently, I have also started to focus on audio manipulation, including simulating microphone re-amping, blending completely different types of instruments (such as analog instruments with synths, or percussion with vocals), and generating synthetic rap vocals that I can control with my own voice.

Throughout your work I find that the concept of interaction is a central one: machine-man, man to man, the individual and the group, visual and sonic languages. AI is not only generative but also perceptual, much like ‘real’ audiences. It simulates neural networks through mathematical abstractions in order to perceive inputs and register them. What is your relationship with audience perception, and how does your knowledge of audience response to an art piece or a live exhibition inform your interactions with machines?

Certainly, the hybridization of various disparate elements greatly interests me. I’m not particularly keen on framing AI as a generative tool. It seems much more intriguing to view it as an agent of transformation and hybridization.

When interacting with the audience, however, I generally do not seek a direct exchange.

“In designing live performances and installation, I always aim to create a significant asymmetry between LOREM and the crowd. I want those who listen and observe to be overwhelmed with stimuli, to force them into an experience that allows for only one possible point of view.”

The work of artists like Kurt Hentschläger or, in some way, Sunn O))), is an example of what I mean, I believe. At the same time, I enjoy embedding hidden references, “encrypted” messages, and correlations, to open questions and reflections through ambiguity. This approach can lead to profoundly deep interactions post-experience. Occasionally, an audience member may approach after a show to inquire about an insight they had or to propose new interpretations. For instance, I once spent an entire evening discussing the script of Distrust Everything with a scenographer who had come to see the work, and with whom I have stayed in contact ever since. Those moments are particularly rewarding, as they allow me to connect deeply with people…

Since we’re discussing languages and interactions, I’d like to make a digression. I began this interview by mentioning the early 2010s: a time of peak music media and blogging. I recall reading Deer Waves (shout-out to Italian hipsters worldwide), Pitchfork, and all the usual suspects. Your work is deeply intertwined with technology and the nature of media(s) itself, with music being one of its key components. I’m curious if you’ve ever considered how platforms and the circulation of music actually influence the composition of music itself. Think about “MySpace Bands,” or SALEM and the emergence of Witch House with its Web aesthetics. We’ve witnessed the era of SoundCloud rap, which is self-explanatory, and nowadays, and nowadays TikTok is shaping how mainstream labels function and the pop songs structures. I’d be really curious to pick your brain on this particular matter.

Distribution platforms and modes of consumption undoubtedly play a crucial role in shaping our aesthetic experiences, and they certainly influence artistic languages, probably as they always have. As I mentioned, the experience of the pandemic and the subsequent changes in consumption habits heavily interfered with the evolution of the project. I doubt I would have moved so close to the narrative dimension if we hadn’t all been in lockdown for months.

That being said, I’m uncertain about the direction that the music industry will head in the coming years. Frankly, it looks like a colossal mess… There are numerous factors at play in regards to that: the need for fairer and more inclusive distribution systems, the emergence of new technologies based on decentralization, the critical role of algorithms in shaping musical trends, and the emergence of “instant” platforms like TikTok, as you mentioned, among others.

Speaking of the evolution of media, I recently read about “neural media,” which K Allado-McDowell has theorized as developing out of network media in the mid-2010s amid increasing human-AI interaction. K’s description of neural media’s mechanics posits the concept that our ideas of individuality and identity formation, as well as what itmeans to communicate as a human (among other living beings), are about to be majorly recalibrated. What role do you think audiovisual expression, a language that is already forward-oriented and one you have been experimenting with for years now, plays in such futurable socio-cultural landscapes?

I can’t give you a general answer. What I try to do and what I recognize in the artists that I admire, is an attempt to produce aesthetic experiences that have a strong emotional impact while simultaneously “showing the scars”, so to speak. Their works create a space of ambiguity useful for recognizing the artifice, and without hiding it. This way, to use a phrase by Hal Foster, “…artifice, the Utopian glimmer of fiction, can be placed in the service of the real.”

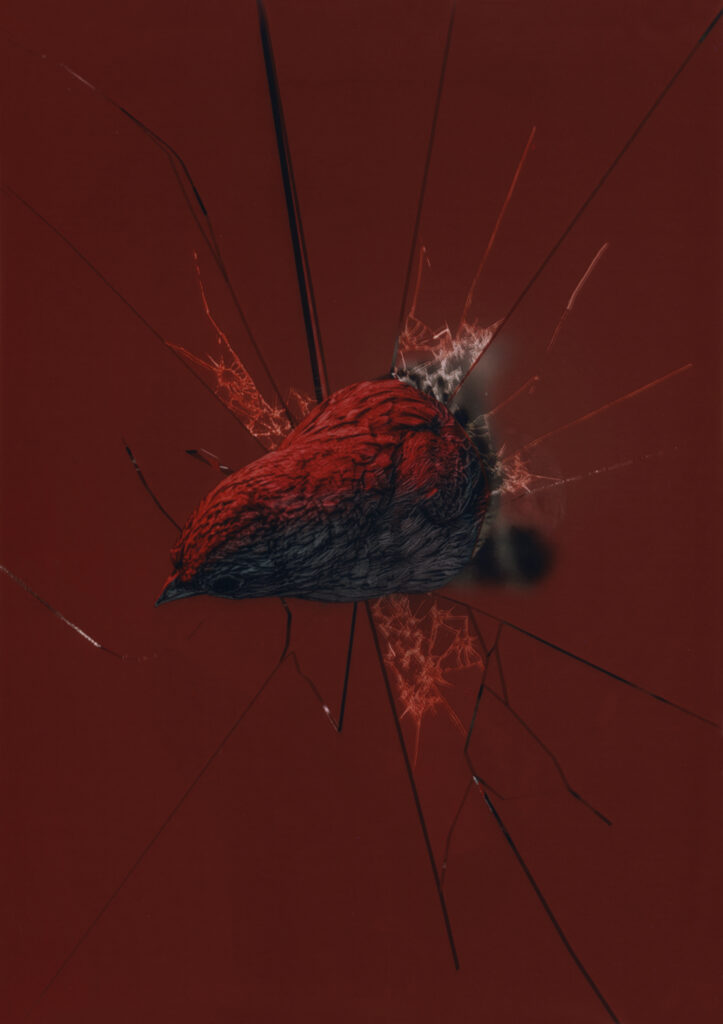

Why did you choose SEAGULL as one of the two singles anticipating the full-release? What drove you towards the concept of flocks and shared-perception, and how does it relate to the record’s structural narrative?

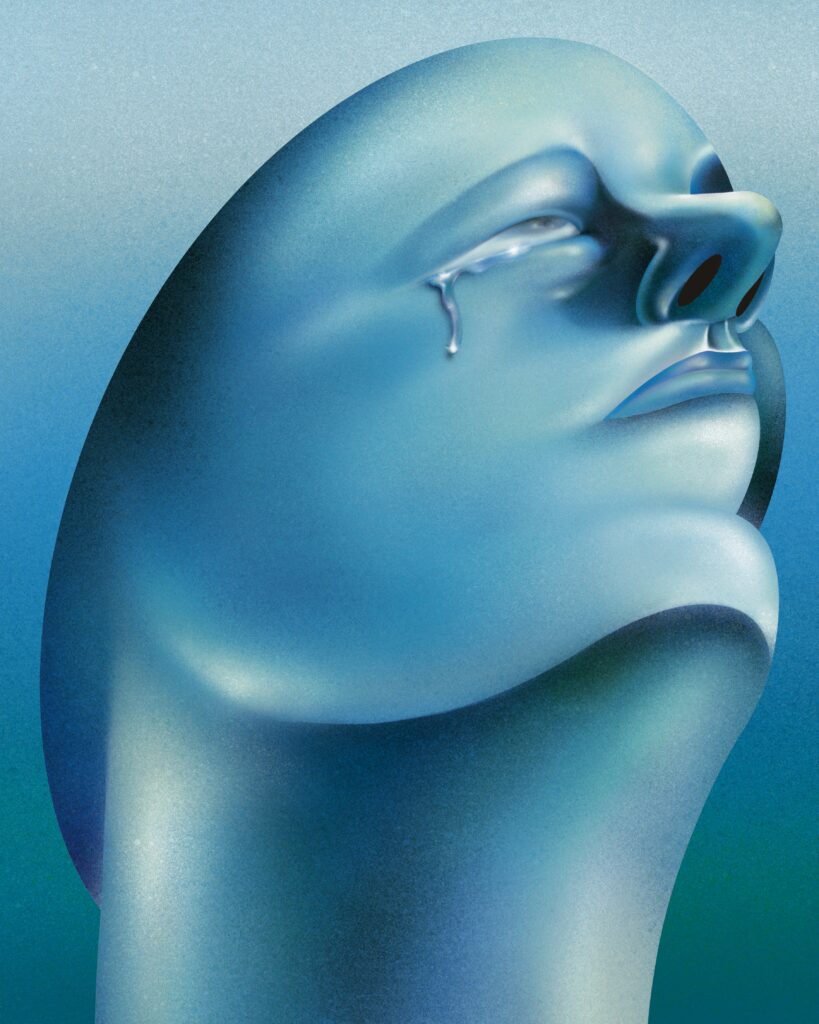

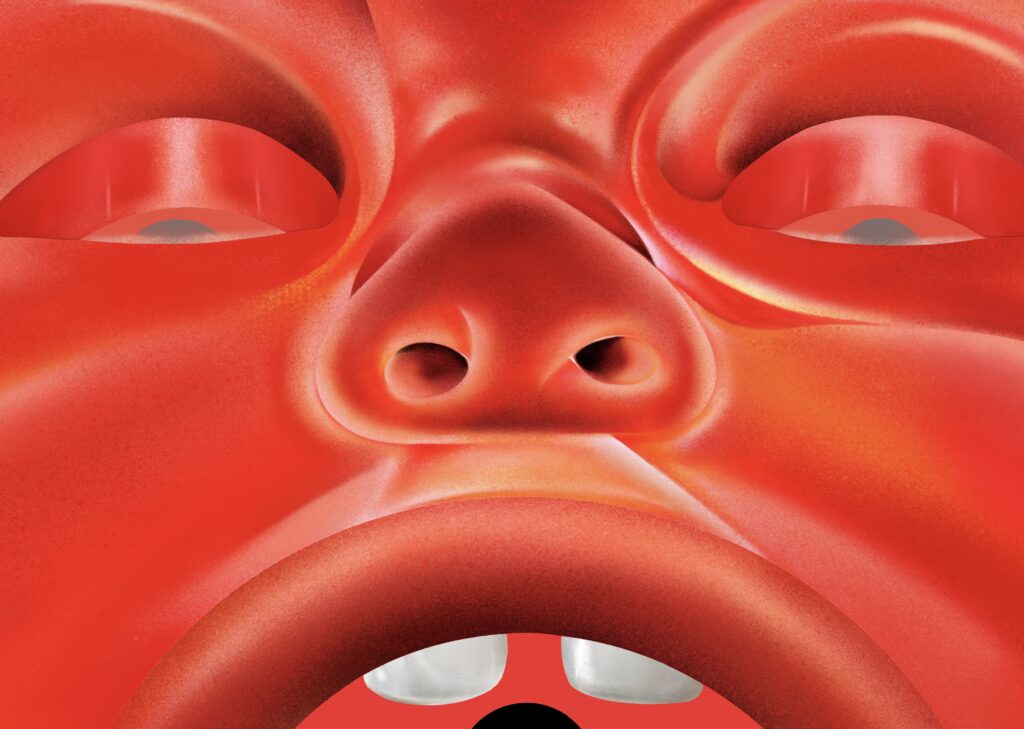

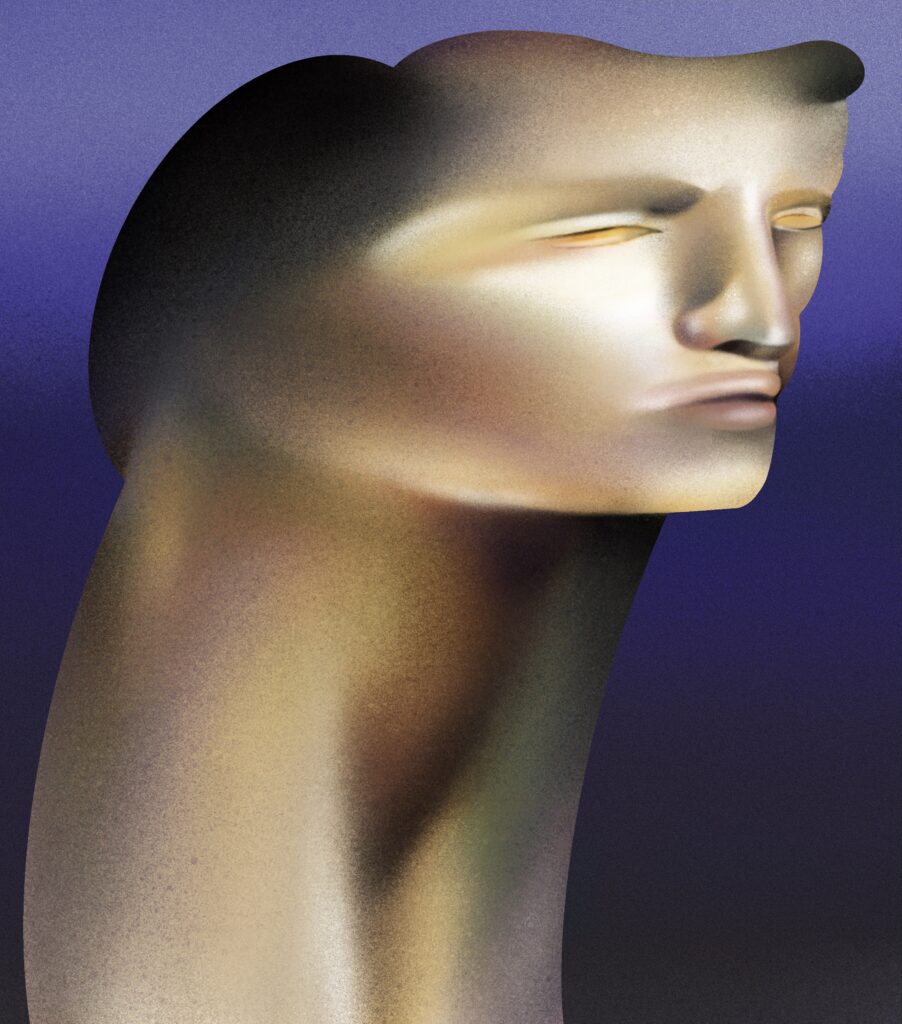

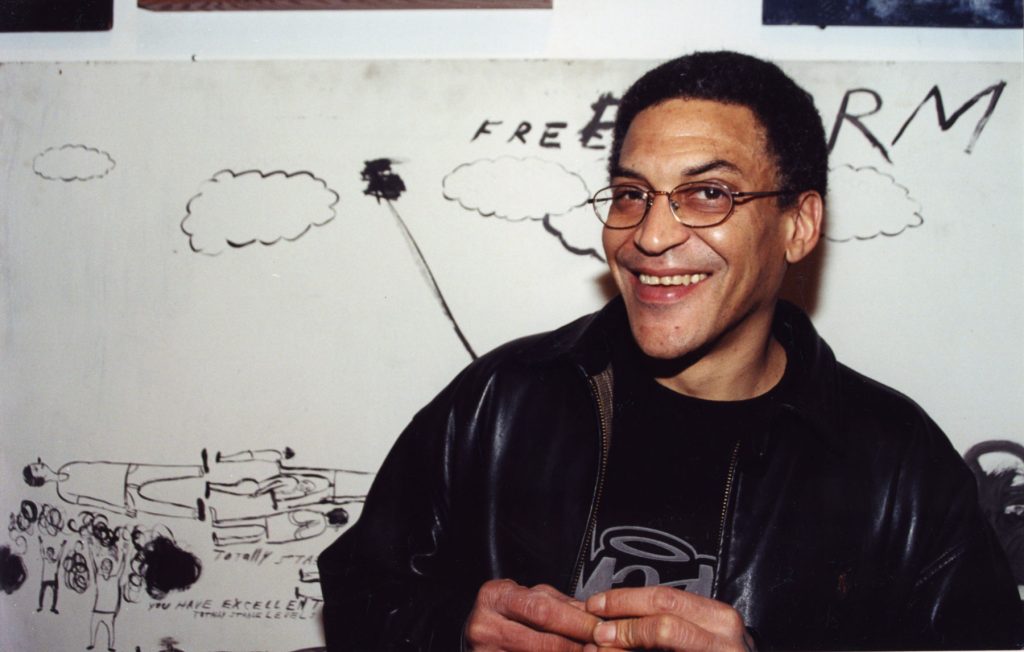

I began working on the video with Karol Sudolski, a friend and collaborator on the LOREM project from early on in the creation of the Album. Karol is one of the people who inspire me to think of LOREM as a hybrid identity, which sometimes speaks in my voice but other times expresses itself as a collective, a chorus. We simply felt that the track was perfect for the flow of the video, which features a single continuous shot within this swamp of organic and inorganic forms.

Are you thinking of other outlets for the Time Coils narration to be experienced? Something transmedial like what you did for Adversarial Feelings, out on the publishing house you co-run, Krisis.

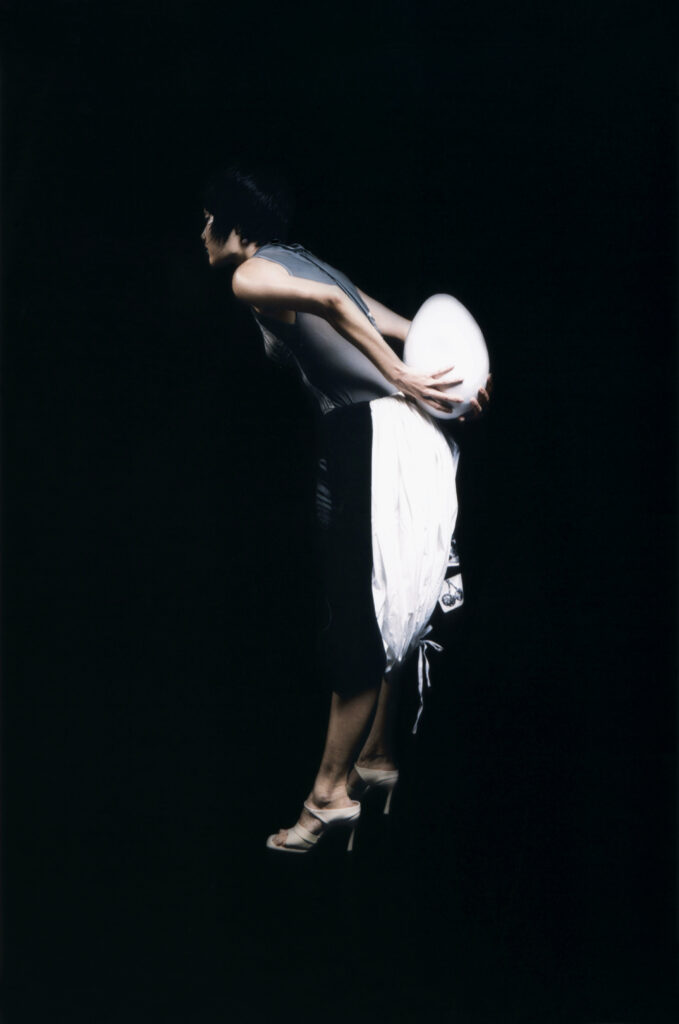

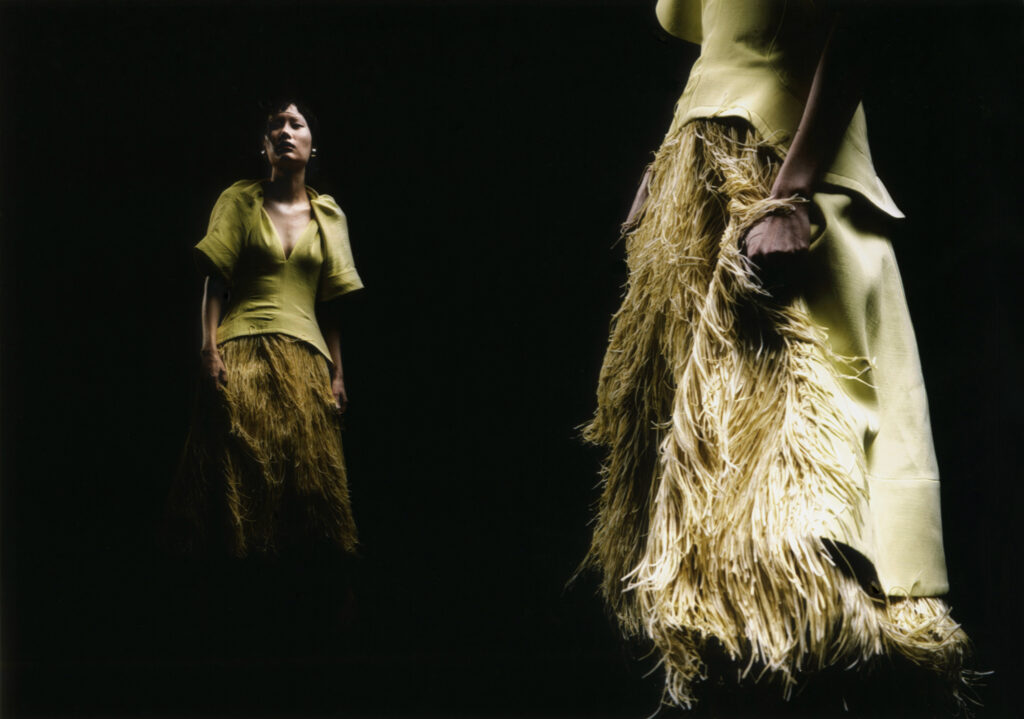

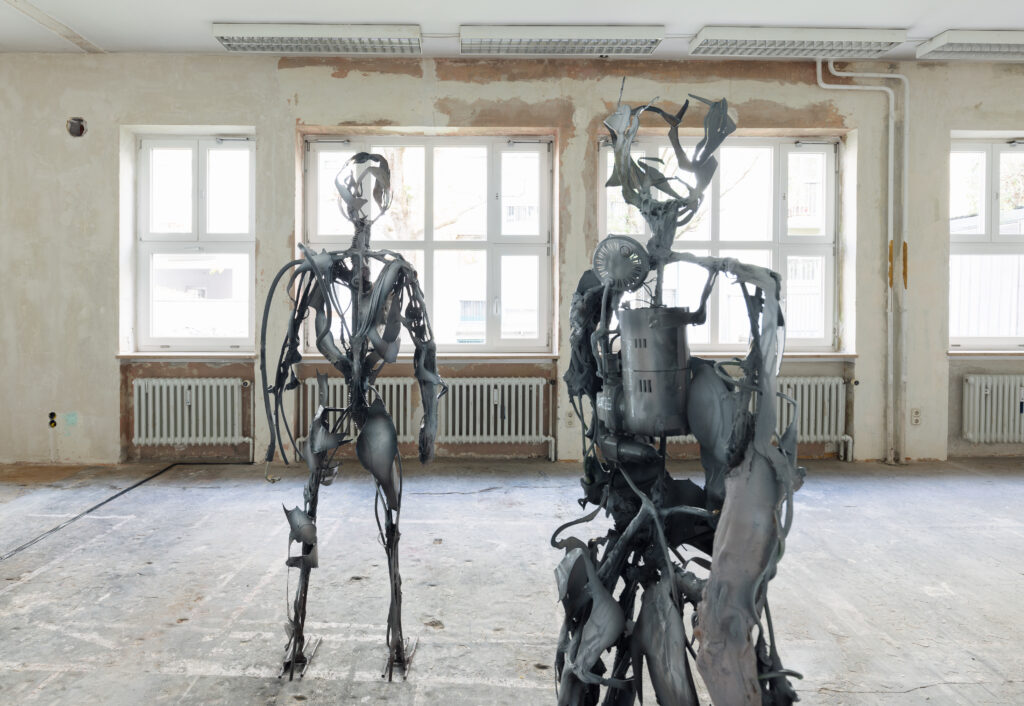

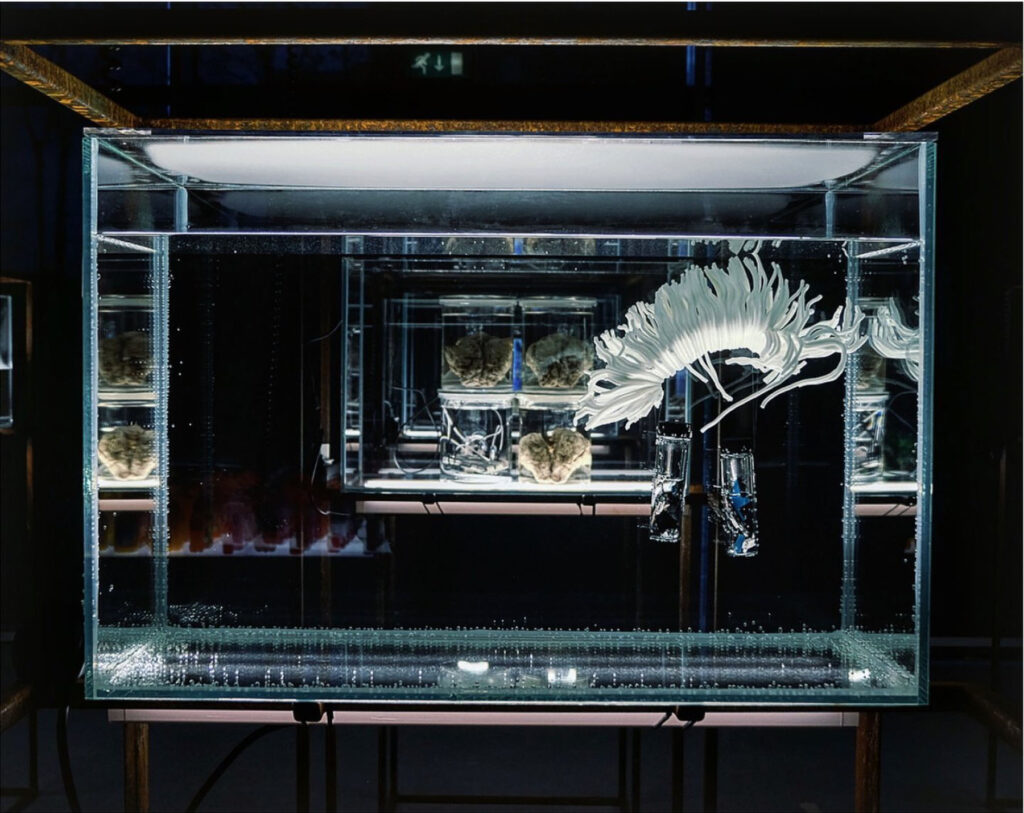

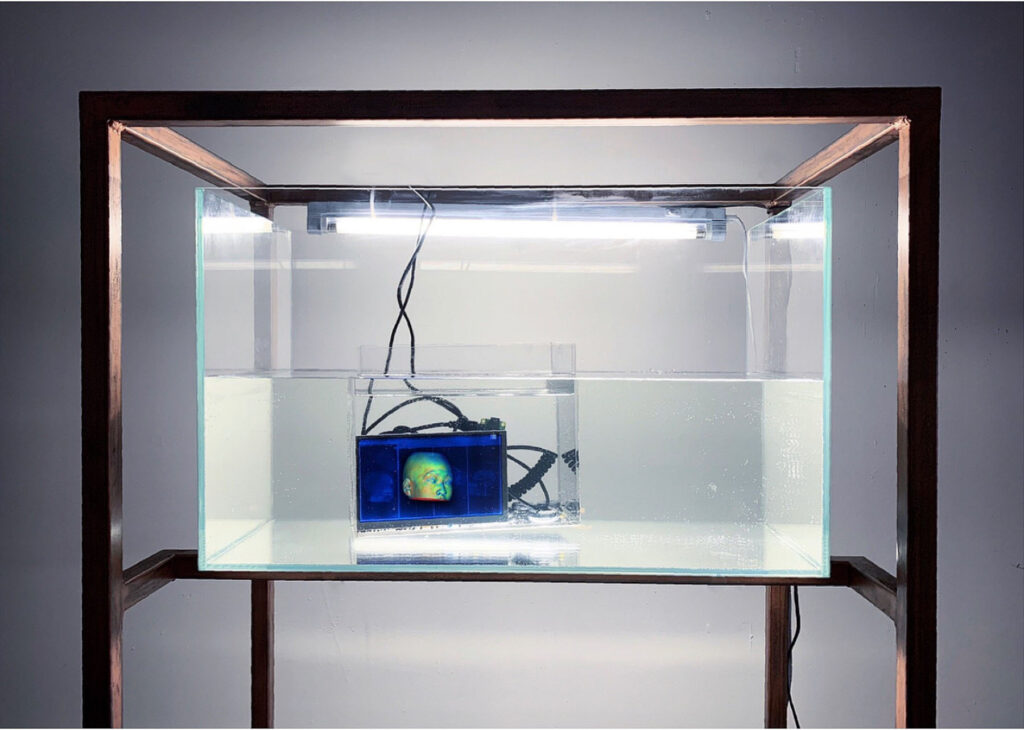

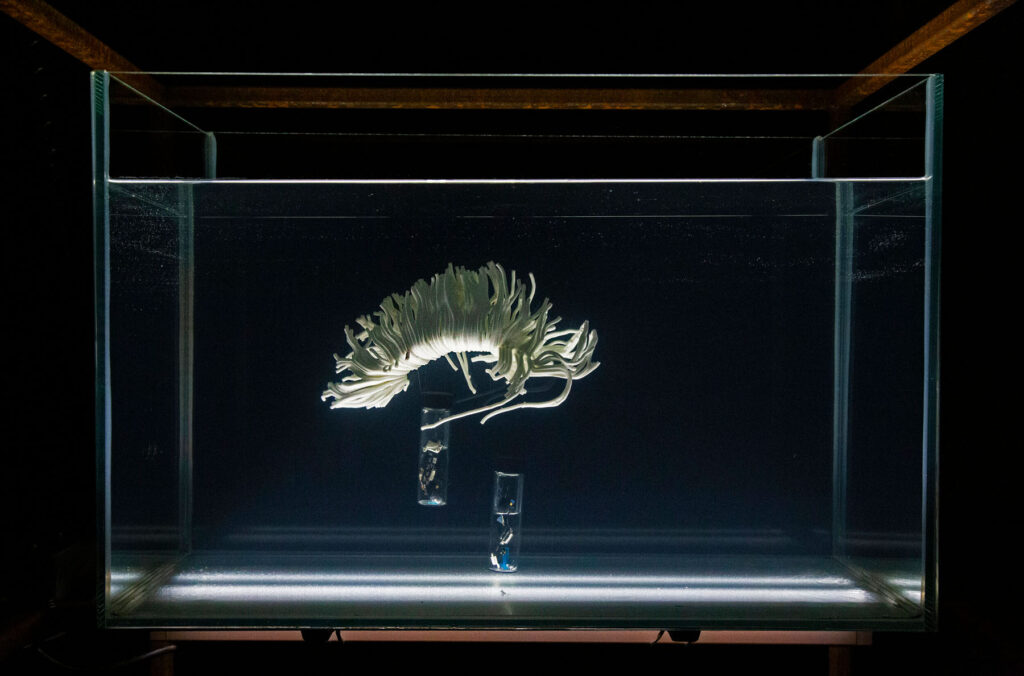

The first is a large-scale AV installation, ARC, which features a walkable dual-channel large LED wall that displays visualizations of contradictory states of consciousness. I created it with Visioni Parallele, and it will debut on Saturday (April 13th) at the Mattatoio in Rome. The work is based on the idea of intertextuality that I mentioned earlier… here, the question might be, for example: what a morph between excitement and boredom might look like? Perhaps something akin to me scrolling through Instagram on the toilet.

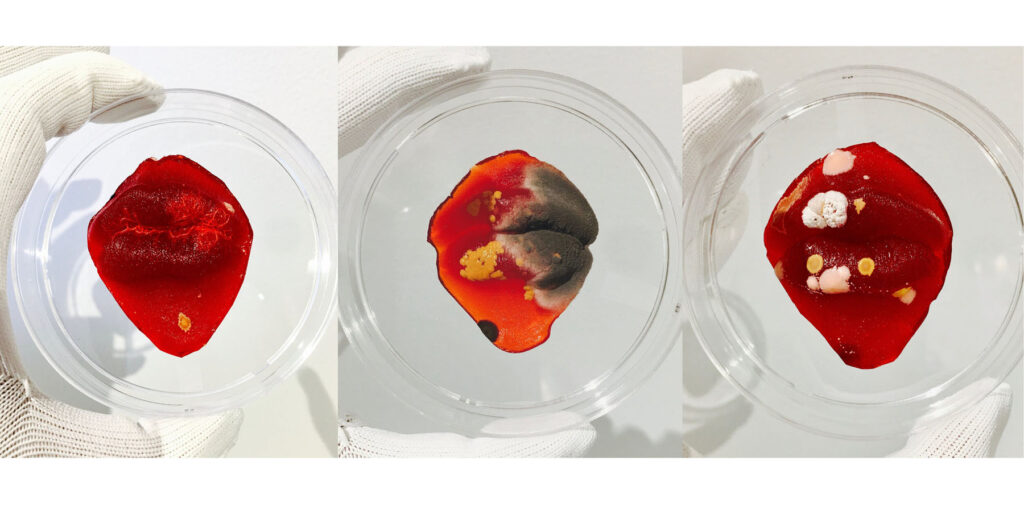

In early May at L.E.V. Festival in Gijon, there will be a new iteration of the Distrust Everything project; an immersive chamber that narrates a speculative dream emerging from Mirek Hardiker’s Dream Report Archive. These projects are in dialogue with the album, in a vague way, because they share the same approach, but they are also related to it as I continue to reuse the same datasets, which keep expanding.

What is Krisis role in the economy of your varied and intersectional practice? Is that a place where you focus more on curating others? Taking a step back from “your” own work and constructing bridges for others?

We founded Krisis Publishing in 2009, and I manage the editorial direction of the project alongside my friend and fellow researcher, Andrea Facchetti. The main focus of our project has always been and remains the politics of representation: we are interested in examining, through various lenses, the impact of media cultures on contemporary societies.

Both of us have academic backgrounds in philosophy and design/arts, which makes Krisis the platform to formalize and disseminate both our research and the works of pivotal authors. We typically handle the editing of the books we publish ourselves, and this has enabled us to connect with artists, theorists, and researchers we respect and admire. Among the notable authors we have published are James Ballard, Timothy Morton, Simon Reynolds, Kate Crawford, Hal Foster, Vladan Joler, Sofia Crespo, and also friends like Silvio Lorusso, Luca Pagan, Filippo Minelli, Corinne Mazzoli, Ryts Monet (just yesterday we launched the pre-order for the book we developed with him).

In recent years, we have begun to move beyond the borders of printed paper. Krisis functions not only as an independent publisher but also as a curatorial platform, producing audiovisual projects, music albums, events, installations, exhibitions, public talks, etc.

Certainly, there are parallels between my research, that of Andrea’s, and the editorial line of Krisis. In recent years, we have intensely explored the theme of the relationship between language, reality, and identity, the political implications of AI’s emergence, and the articulation of ecological perspectives. In a way, Krisis serves to me both as a source of input for LOREM and an opportunity to translate into theoretical language the issues that concern the project.

Last but not least..Nomen Omen. Why LOREM? A nod to unfinished but in-itinere linguistic forms?

Lorem is a model for extracting correlations within corpora of unstructured texts.

When I started working with texts and machine learning to enhance the emergence of intertextual correlations, I began by removing all character names from the literary texts in the datasets. I wanted the machine to confuse the characters, thereby overlapping the information pertaining to each. I have now started to group different types of characters using different letters (L, M, D, etc.), but initially, all characters in my datasets were named LOREM. When it came time to name the project, all these LOREM’s were already there…

Interview · Andrea Bratta

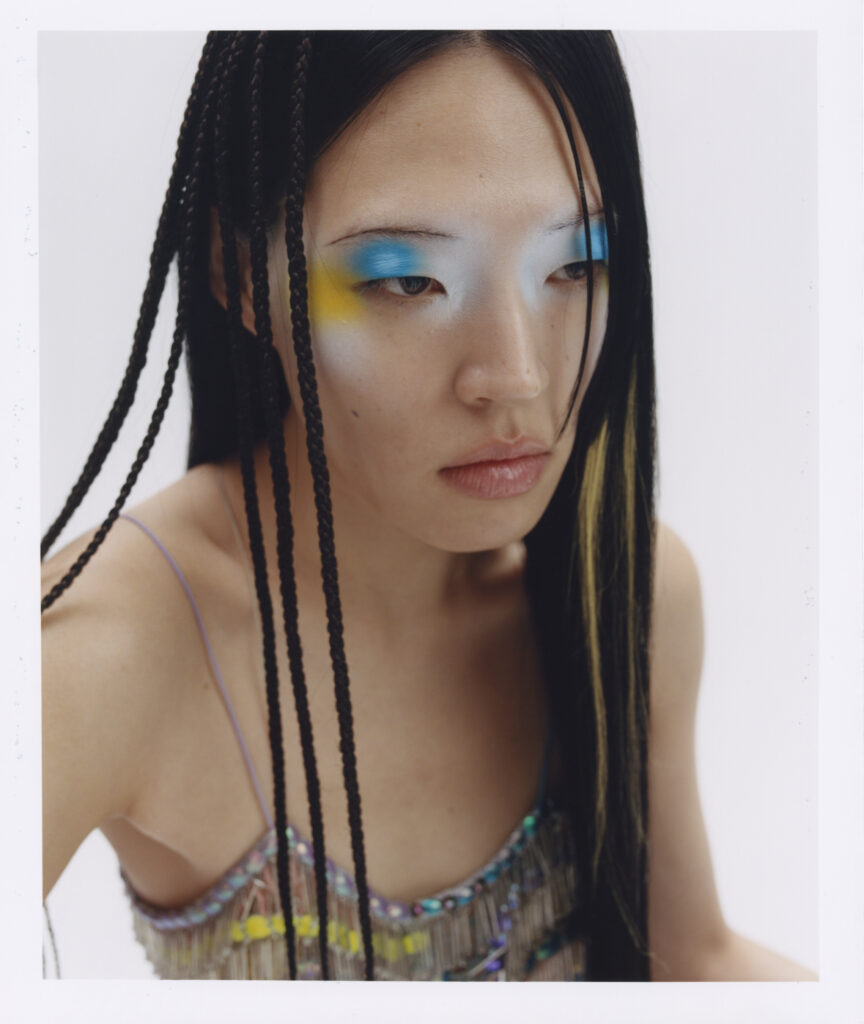

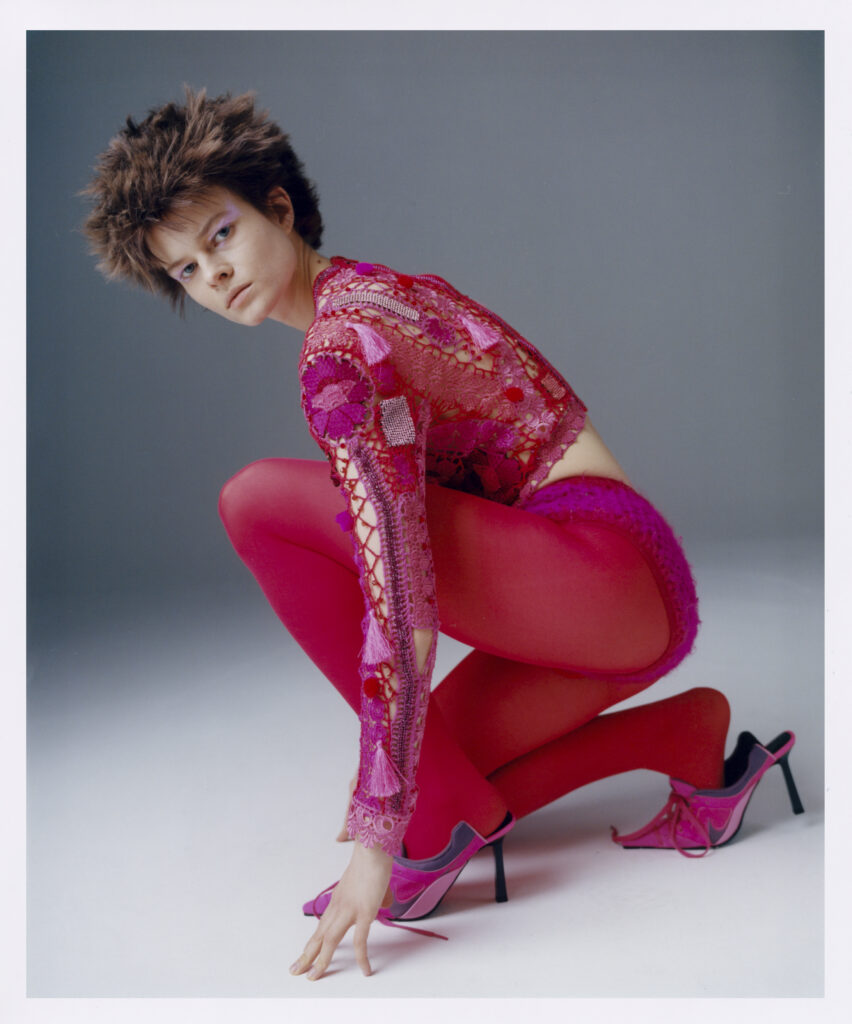

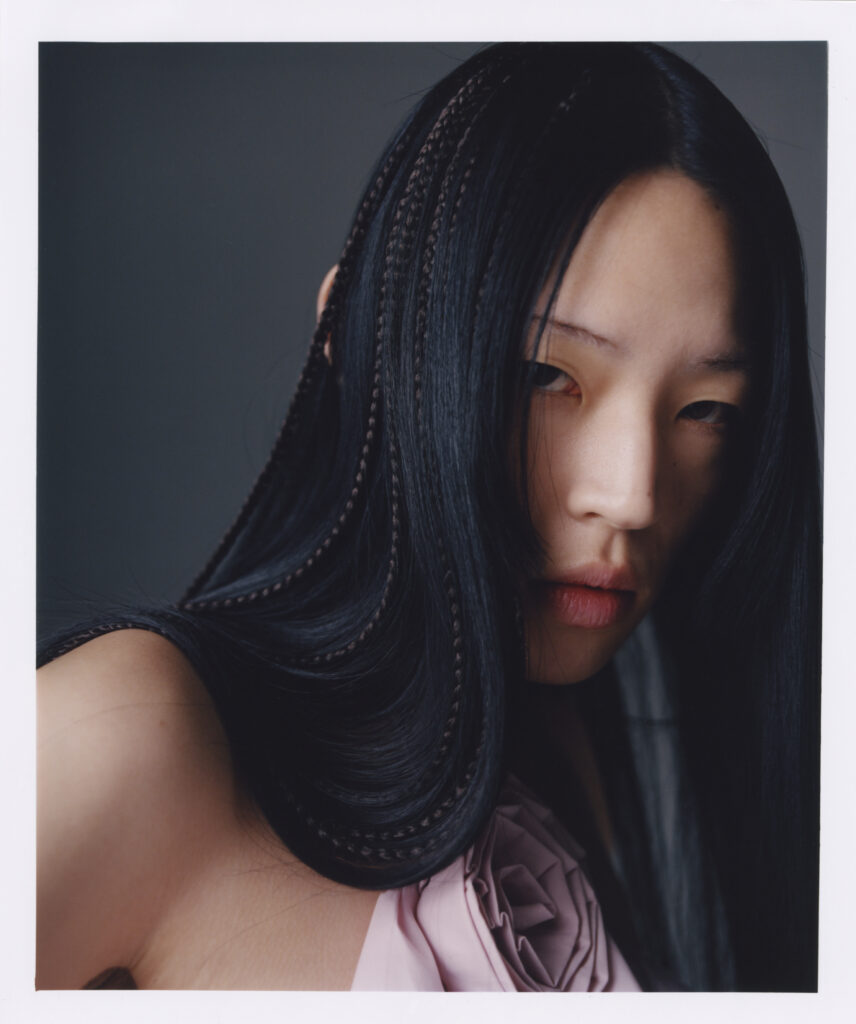

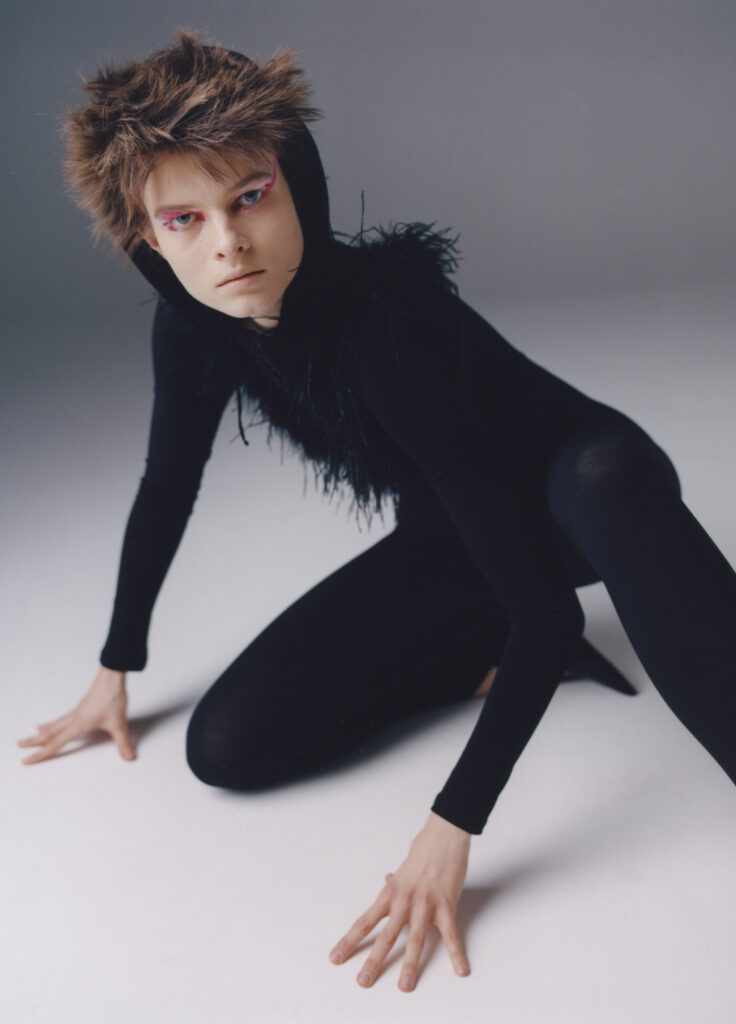

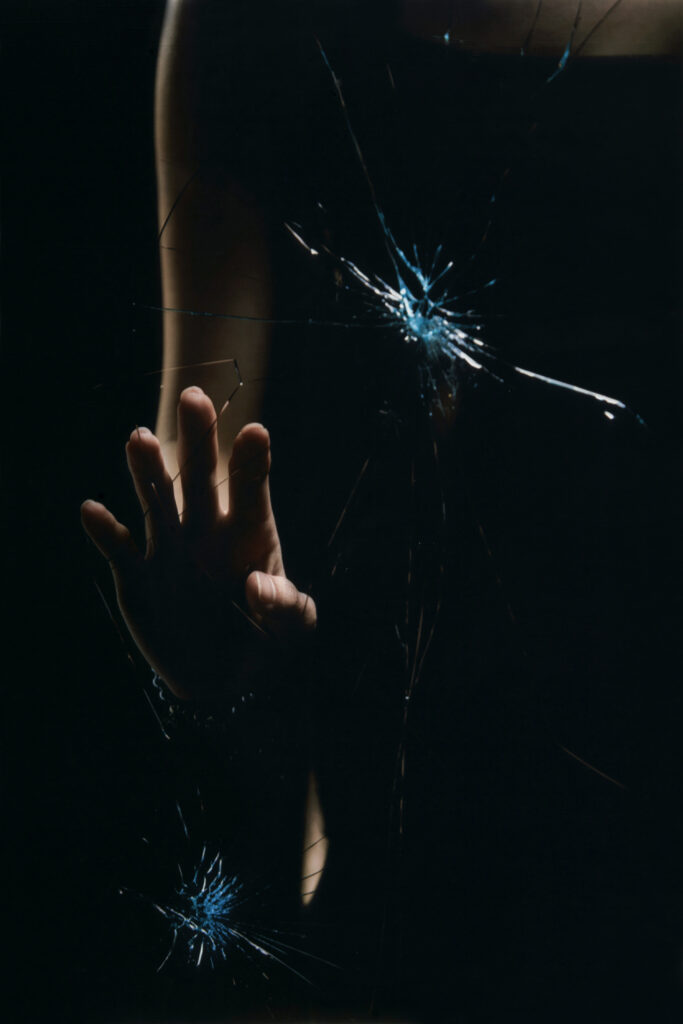

Photography · Omar Golli (ARC Installation)

Time Coils out on 26.04.24 via Krisis Publishing Pre-order the album here.

Follow LOREM on Instagram and Soundcloud

Follow NR on Instagram and Soundcloud