The engine is off and the streaked windshield faces away from but towards. The faded parking stall lines of the empty lot are blanks waiting to be filled in by old habits, starved but undying. Between the spaces where things fall, the seat and the idle transmission, things get lost and lose their edges, soft callused hands reach for absent haunts, memories of. Then the pedal is released. Other cars whiz by, towards, but away from.

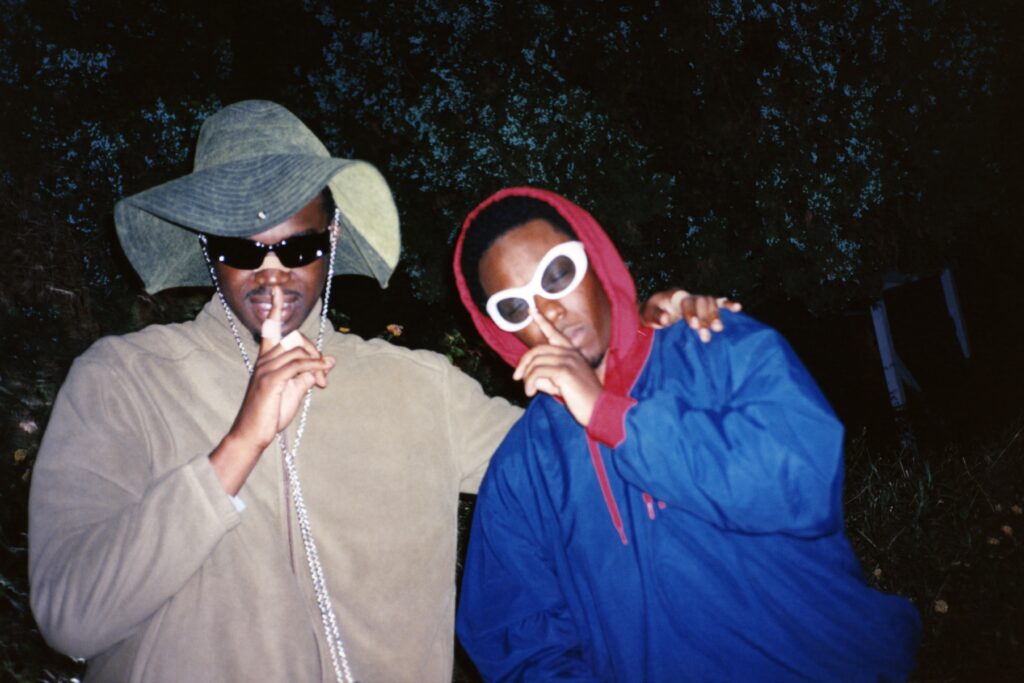

Louie Pastel and Felix, members of Paris Texas, take this call from their respective driver’s seats parked somewhere in Los Angeles. The sounds of the road muffle their voices and we leave our cameras off so instead I stare at circles – Felix appears as a grizzled Michael Jackson and Louie’s as the Mekhi Phifer Smoking Reaction meme, his name appearing as “That Guy”. Felix comments on the persisting gloom, a never-before setting in the City of Angels they call home. But as is often the case for Louie and Felix, there is something more to glean from circumstance. As if the gathered clouds were mirrors for the fires of this enduring retrograde, the smoke of cynicism, nihilism, all the -isms, burning holes in the things we hold dear. In this altered atmosphere, dystopia is rendered a collective emotion, we define “connection” by the amount of bars we have versus the feeling of having someone walk you home. Felix and Louie absorb this energy, observe the shifts and translate them into radical honesty reflective of the cultural climate today – can we run that back?

Paris Texas as a group, as a sound, is unbridled, an act of distortion perceived. Fans have likened them to delivering the unexpected, they’re “different” and hence, “refreshing” – unzipping musical genres while asking us to let go as part of the experience. As they gear up to release their full-length debut album Mid Air this August, they crank the steering wheels to the left, beckoning us towards the godforsaken – vulnerability, singularity, and self-awareness. Though the guys see themselves as “silly,” through the intersections they’ve built between sound and visuals, reality and delusion, id and ego, it becomes glaringly evident that they aren’t just on the map, but are making it.

Lindsey Okubo: I know you guys just released your debut album titled Mid Air and I was taken aback by the last two tracks, Ain’t No High and We Fall because they seemed to embody a new level of vulnerability lyrically. If Boy Anonymous was about y’all figuring things out and the mystery that comes with actualization, this one feels buoyant, sanguine and ultimately, assured..

Louie Pastel: Yeah I felt like two years ago when we really came out, it was like, damn, we got the attention on us really fast but the lyrics were kind of just fun and we weren’t really talking about anything. We tried here and there but we didn’t give people a lot. This time we gave people a little bit more and practiced the vulnerability part so our audience could get to know us.

Felix: We don’t always publicize our business. However, it was important to give people an update within the music. It’s a lot more therapeutic this way and there are different avenues for that but this one just feels better.

L: Right and I like the way you phrased it in calling it “the practice of vulnerability” too because it is something that you have to be cognizant of. What’s given you the courage to own your artistry more as you step away from relative obscurity?

F: We don’t take ourselves too seriously, we’re not pretentious but we can be meticulous in certain ways. Anonymity requires a way bigger team and series of events in order to execute it in a way that feels successful. We live in such a time now where everything is unveiled and people are finding things out all the time whether you want to call it research or not.

L: Yeah and tangentially, visuals have always been a huge part of what you guys do, allowing you to develop a whole other language and sensory medium to be understood through. There are elements of horror, nostalgia and surrealism that mirror this wave of escapist and nihilistic predispositions that our generation has been riding. Any thoughts?

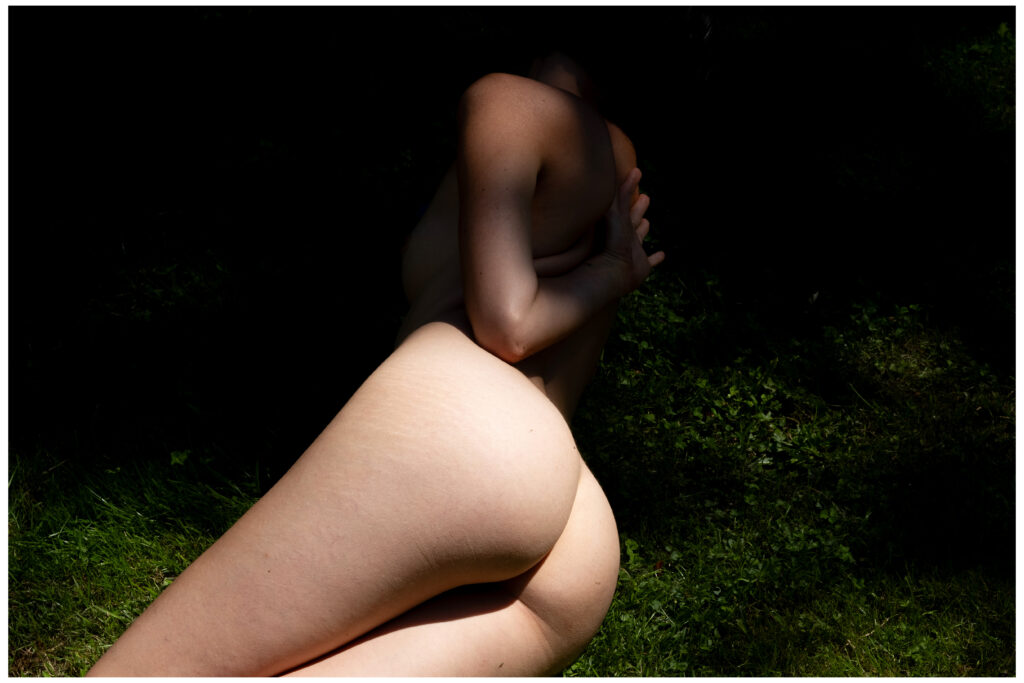

L: Yeah it’s interesting because everybody’s kind of incentivised to be performative, especially in this online era, and we’ll get rewarded by this positivity most of the time. It’s really eerie, really dystopian and I see that and I’m like damn, if this changes in 20 years we’ll look back and ask, what the fuck was everybody on? I just try to give my perspective where I’m not pretending to be ultra-tough or extra flashy, I just want to paint a real picture of certain things. The first video, HEAVY METAL, was just us having fun and after that we wanted to show this parasocial relationship between men and women like we did in Girls Like Drugs. Men have this access into women’s lives so much and it’s in such a nasty way that we have a relationship with them. Guys be looking at girls all day, being actually horny about it. It’s like you don’t know this person, why are you sexualising them this much? We’re constantly watching and creating a fantasy in our heads that numbs us to any actual connection you can have which is why we depicted ourselves in the video as being behind the mirror or under the bed. We see her but she can’t see us. It’s doing shit like that instead of smiling, dancing and putting on a show for people.

F: It’s a satirical take on things for sure. Whether Louie comes up with an idea and I’ll piggyback off it, or we bounce things off each other, the ideas feel natural. It’s this weird, intuitive thing that happens because not every idea is always hyper-intentional in the moment. But when we start to refine it there are important messages that are revealed to us. Our subconscious has been holding onto what’s been going on us and it always just so happens to align with what’s been going on in the world around us. Even in these past few years I’ve seen a shift in how people were on top of self-care, on top of being conscious and aware and that was glamorised for a long time. Now you have people glamorising being depressed but also tying that to whatever their libido is on. The only stimulant or dopamine, if it’s not drugs and indicting yourself in that, are sexual pursuits.

We were in New York last week and that was a funny situation especially with the wildfire smoke and even in Los Angeles, it’s been gloomy for the past two weeks. This is the longest it’s been gloomy ever, with no rain, it’s just been cloudy. It’s interesting how that’s playing into our concept for the new project and is reflective of the climate of everything and how dystopic everything is becoming.

L: Yeah and you guys used the word “connection” and it’s ironic because in victimising oneself, people are often closing themselves off from attaining the very thing they want by claiming that. With music, obviously, it’s an emotional thing, there’s nonverbal nuance, lyrics as conversation, chords as language and I’m wondering how you guys define connection in and through your music? There’s also so many different styles of communication, what kind of communicators are you?

L: I think we’re really good at connecting sonically, me and Felix relate to each other so well. I don’t make music and worry about how it connects to people lyrically because we’re not that pretentious, we’re silly dudes. I think the way we present our shit to people is just inspiring people to keep pushing for something different. I don’t know if my story is that relatable to everybody and if you’re not an artist it is hard to relate to as well. Sonically and lyrically, I think it’s about pushing the weird shit, the different shit because the best thing you heard this week isn’t the best thing forever. Don’t stop, let’s keep going left with it. I want to keep connecting with people who want to keep going left as opposed to staying in a certain pocket.

L: Where does going left lead? To freedom from performativity?

L: I think it allows people to just think differently and I think that that’s the only way we can evolve as a people, is doing that. I think if they see two fun, silly guys keep doing the thing then people will know that it’s okay to think differently, it’s okay to move differently, and not in a performative weird way but the actual way. The more that people like us succeed, the more confident people will feel about not being so bland.

L: I feel like “difference” is ultimately about honesty and even with the name, Paris Texas, it’s about distorting perception and y’all are two Black kids who didn’t really feel like you belonged but found outlets that warranted connection. It’s an important reminder to have that ultimately connection isn’t just made but found. How much of where you guys are is due to that sense of lack – whether it was belonging or means and how present is an active sense of rebellion in your minds?

L: Like are we practicing being different? No, it’s something that already was and it’s not something I have to try to do, it’s what I am naturally. When I was younger, I had friends and family who conformed, were more straight and narrow and it worked for them, it’s not wrong but they thought getting me to conform would make my life easier but every time I tried, it just didn’t work. Going back to what we said earlier, I know there are a lot of people like me who are having a hard time and sometimes you just need somebody to show you how to move, you need to speak for those people.

L: Who are you guys speaking for? And for the straight narrow folks in our lives, how much of that is rooted in a sense of safety or stability and what driving force if any are those things in your lives?

F: A lot of the time it’s being able to follow the trail of your curiosity and having the space to think about things, that’s really what it is. No matter if you’re someone who is extremely fortunate or not, you’re trying to find ways to make it out of something. People are a lot more complex overall but they don’t always have the time to understand their identity or things about themselves that can benefit them and what they want to do. I think that’s what safety is really because it’s not necessarily relaxing but in having the time to entertain parts of yourself, you find out who you are.

L: It’s also about even being self-aware enough to want and need that time and space because life moves so fast and one of my biggest fears is waking up and being one day and being like, how the fuck did I get here? I feel like with the way things have happened for you guys, you understand these notions of speed, time and change which are such existentialist concepts and I’m wondering what your relationship to change is in general?

F: It’s just life bro, change is gonna happen. Hopefully you’ll be lucky enough to be like damn, I remember when it was so crazy. Everybody figures out a way to adapt one way or another.

L: You just live through the time and you can’t control it. What I struggle with too with change is that even when you want to change, you still can’t control it. It’s like saying I want to be this person tomorrow but you can’t control how that happens, you just roll with the punches.

L: Felix, I know you have especially talked about having faith in what you guys were doing and Louie, you had your like scumbag era and maybe that notion of having faith in something is maybe the only way to “control change”. Can you guys speak on self-doubt and on the flip side, what faith really looks and feels like?

F: I feel like it’s understanding that it’s just always going to be a thing. The mirror of yourself is constantly overlooking and overshadowing and you’re always going to think about what other people are gonna think. A lot of people say that it’s usually a good thing and it lets you know that you obviously really, really care. Faith and self-doubt complete each other because you’re only doubting yourself so hard because you want it to be so great, you love the process and you want it to be as good as possible.

L: Self-doubt and faith often get combined and they play with each other and become self-awareness at some point. I never have self-doubt really, it’s more so wondering where I’m going to fit into doing this thing and if people are gonna like it. You need the community, you can’t make music and be like, I’m the greatest. The community around you has to make you what you are so anything that would be considered self-doubt for me is just being realistic. I’ve never really doubted us at any point, I knew that shit can was going to be hard but it was gonna happen eventually. I never had impostor syndrome, I’ve just had this is where I belong type energy.

L: You guys were talking about those moments where you recognize yourselves in the music and moments where you don’t and therein lies this suspension of belief almost. I know sometimes artists see their artistry or practice as separate from who they are as individuals and I’m wondering where you guys draw the line?

F: When it comes to music it’s so weird because you always listen to yourself and you’re like, oh my god, that’s me, okay cool. The best moments are when you take a break from it and you’re like, I don’t know who that guy was that was on the song – and I know it’s me – but it’s like that was crazy. I don’t even care that it was me, it’s just like, oh shit.

L: I love making a song and it’s like dang, I’m listening to this as if I’m listening to one of my favorite artists.

F: Yeah like I’m listening as a listener. I don’t have the pressure of being like my voice sounded weird or the beat is fucked up here, it’s like like whoa, what an experience. [laughs]

L: If I make a song and I don’t feel like it’s me personally on there then my job is complete because I’m hearing it as a fan would hear it. Sometimes I’ll make a song where I’m like, oh, they’re gonna fuck with this because I fuck with this. I’m listening to it like, oh who the fuck is this? It doesn’t feel like government name, grew up here, did this, it feels like who is this guy? I’m a fan of him.

L: Yeah and these notions of legacy are also tied to music where you have this ability to live on far beyond your time or after you’re gone. What is your relationship to the word legacy?

L: It depends, legacy is cool but I’m not a legacy guy, I don’t even want kids. It’s what the people decide to do with it but to have an impact on one person’s life is enough. I’ve had bands that no one’s ever heard of before in their life, 10,000 views dropped the song in like fucking 2006 but I still love them and they have an impact on me. If one person who is not a friend or someone you’re related to is like, I fuck with this thing, that’s so importantIt’s a crazy thing to make something and somebody is like I resonate with that. People take legacy as a means of saying your impact was huge but that’s some industry shit, it’s a game you have to play.

F: We’ll see man, it won’t matter, I mean it will matter but we’ll just see what happens.

L: Also thinking about the nuances between pop culture versus art. With pop-culture you’re measuring impact with virality and inferring that it equates to emotional resonance or understanding but I think there’s a difference between those things. In pop-culture, the message often exists in a watered down version of itself, it’s digestible to the masses and with music or art, you have an opportunity to create something truly singular.

L: Yeah for sure, it’s a whole different thing. Pop culture is interesting, we need it but I think a lot of people don’t want to invest the time to connect with their feelings. I remember this one person I was talking to told me that she wasn’t a fan of music, which was crazy to hear. There is a majority of people who are not fans of shit. Meanwhile, we like all these weird little things and can argue all day about them. Even the question of pop culture versus art, the average person doesn’t really care. They’re like, does it make me want to dance for five seconds? They don’t even care if the creator disappears, being popular is a matter of the now, looking kid and if the kids like it? Fuck it. Pop culture can just go away. Like Picasso isn’t pop culture, people who make art aren’t pop culture. He’s popular, but he’s not pop culture.

L: Yeah everyone’s lost in the sauce. Do you guys believe in true love?

L: It’s funny, I think sometimes people think that true love is from person to person but I don’t think it’s black and white as that, sometimes you can love something and you truly love it, it could be art, a hobby, a smell. I believe in it, truly.

F: It’s almost like a nirvana state in a sense, there are just so many ways to go about it. Love in itself, a lot of people see it as a limitation but it’s a word that can contain so much more than what it is that it becomes malleable but somehow we’ve reverted it down to a shape.