I try to sit on a fence where one foot is in one world and one foot is in the other world

Richard Kern, the iconic photographer and counterculture figure, has been capturing the gritty, unapologetic essence of downtown New York City for over four decades. His work explores themes of sexuality, fetishism, and power dynamics, pushing boundaries and challenging societal norms. Kern’s photographs are a raw and honest reflection of his subjects, capturing their vulnerability and strength in equal measure.

Born in North Carolina in 1954, Kern moved to New York City in the late 1970s, quickly becoming a fixture of the city’s underground scene. He began his career as a filmmaker, producing a series of experimental films that explored taboo themes and challenged traditional cinematic conventions. However, it was his photography that would ultimately earn him widespread recognition and acclaim.

Kern’s work is characterized by its rawness and intimacy, with his photographs often featuring his subjects in unguarded moments. He has a unique ability to capture the complexity and contradictions of his subjects, revealing their innermost desires and fears. His photographs are not for the faint of heart, often depicting explicit sexual acts and fetishistic scenes.

Despite the controversial nature of his work, Kern has maintained a loyal following of fans and admirers throughout his career. He has exhibited his work in galleries and museums around the world, and his photographs have been featured in numerous publications, including Vice, Purple, Interview, and i-D, just to name a few.

In this interview with writer Federico Sargentone, Kern discusses his approach to photography, the themes that inspire him, and the challenges he has faced as a counterculture icon. He offers insight into his creative process, sharing anecdotes and stories from his long and storied career. Through his words and images, Kern invites us to explore the darker, more complex corners of the human experience, challenging us to confront our own desires and fears.

I was reading the essay Matthew Higgs wrote in your catalogue. I’d like to start there, with the definition he gives of your practice as a portraitist. What do you think of the status of poetic portraitist that you have acquired in the art world? Does that fit you? Or is it something that maybe people have said about you that you don’t like?

I like that definition. I’m glad that Matthew made that definition, even though I wouldn’t have necessarily come up with that myself. Still, it’s very convenient for me to use in my bio. You know, if you’re an artist and a critic kind of clarifies what you do for you, it may sometimes come off as unsettling. But I’ve known Matthew for a long time, and his definition was a nice, precise way to look at myself, which I had never done before if that makes sense.

Do you usually try not to analyse your work by yourself?

Oh, you can’t help but analyse it, can you? I studied art and philosophy. And one of the things they taught in art theory (or whatever you wanna call it), this is back in the ‘70s, was that you had to be able to construct a system of meaning around your work. It had to relate to you and have some kind of justification. So I’m constantly trying to justify everything, myself, but not necessarily in public. And I gotta say a lot of those naked women photographs are very hard to justify.

I’m sure! Even though that is still within the canonical form of portraiture, there is a rich history there that you could go over.

I didn’t realise it at the time but (that type of portrait) is quite confrontational, my old work was all confrontational: the films and things like that were extremely in-your-face — the emphasis was on trying to provoke people. The naked women stuff or naked men or whatever is also a cheap way to create big controversy. The trick for me is to instil in the picture some kind of meaning that the viewer would have to get past the controversy to see. But this method is not applicable to every single photograph, of course. You know, there are a lot of photographs of just people standing around looking pretty or whatever.

Yeah, absolutely. We could also say that the controversial element if you will, is part of your formal delivery of the work, right? It’s as if it’s a technique for a painter. It very much does a similar trick for your images, no?

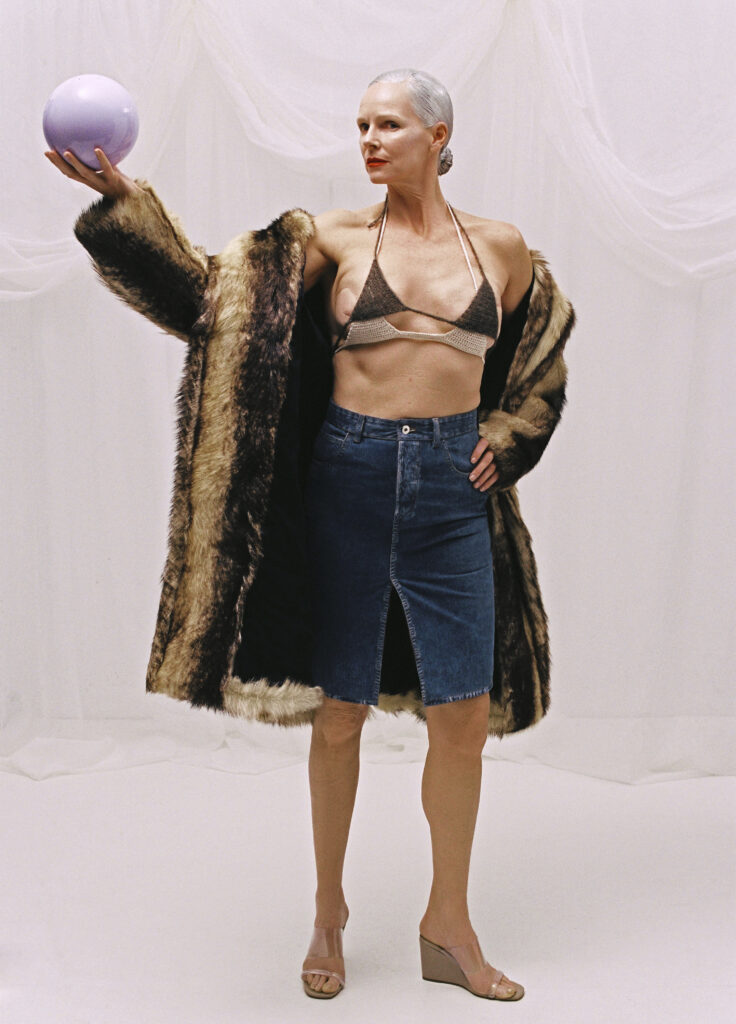

I try to sit on a fence where one foot is in one world and one foot is in the other world. But, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve mellowed quite a bit and don’t feel as confrontational as I used to, in my work. I am so far removed from it, I can’t even tell, you know? Maybe it is controversial. I have no idea anymore.

Did you face a lot of backlash throughout your career?

Oh yes.

And how did you cope with it? I am very curious about it. Was that something you went for, in a way? Or you weren’t expecting it?

For me, the logical thing was to be provocative. But then I’d go, ‘What do you mean, I didn’t do anything!’ It’s kind of like that, this weird attitude of provoking people, and then not understanding why they are upset. That has happened to me so many times! I thought what I was doing was completely fine, but then it really bothered people. Then again, I don’t claim to be super intellectual, super smart or anything.

It’s not a matter of claiming it. But if you look at how, perhaps, a new generation of photographers-slash-artists are incorporating that same aspect of controversy in their work, they are super indebted to your ethos. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Haji Shin, she’s based in New York and I think she incorporated in her work your legacy of controversial image-making. I think that the controversial element has been quite adopted as a language nowadays.

That’s probably true, yeah.

I’m not familiar with a lot of people’s work nowadays, but I do notice that it’s definitely more women photographers doing that kind of stuff than it is men. Most of the photographers I know now are young women.

Yeah, 100%. Critics have described your work as voyeuristic.

Yeah. I totally agree with that one. Every photographer is a voyeur, in a way, I think.

What’s your relationship with that claim?

Oh, I’m totally aware of that and down with it. I mean, my best days on the street are not so much in the winter, but in the summer. I have this little tiny camera I carry around, I get a lot of great shots and just beautiful people on the streets. And a friend of mine described this as, quoting a poet he knew, a two-minute romance, where you pass someone on the street, and you’re in love with him/her for two minutes.

You don’t catch their eyes but see them as you go. Then you continue with your day, you know, keep walking. I’m taking photos of a lot of these 2-minute romantic people. Most of the time I don’t even know what I photograph, because I’m not looking through the lens. I’m just holding the camera down in my hand by my side. I get home and I go ‘Oh, I can’t wait to see what I photographed.’

I look at the photos, and sometimes I realise I’ve got really great stuff. But I can’t even remember seeing them, you know?

But anyway, that’s a strictly voyeuristic thing. And I also shoot photos out my windows all the time. I’ve got an apartment in Miami Beach for the last two or three years, and I’ve been shooting people on the street out my window, walking onto the beach and stuff. That’s just an ongoing thing; sometimes they see me photographing them but usually, they don’t.

“I’m a voyeur, and always have been.”

Do people get offended sometimes?

I can stand in front of someone, look at them, and when I put a camera in front of my eye, they begin to look magical. But that’s regarding a regular shoot. I shot someone yesterday, it was a fashion job, and I’m looking at the photo through the camera going, ‘Wow, she looks really good’.

How’d you come across the fashion-image maker career?

I don’t know; honestly, I’ve been doing it lately to pay the bills.

It is something you might enjoy, no? As a professional practice.

It all depends on who I’m shooting and the situation…sometimes it’s fun and sometimes it isn’t.

There have been years where I do it and periods where I don’t, but lately, I’ve been doing a lot of it.

And at the beginning, were you treating it as an art project?

No, it’s more of an occupation thing, but I tried to get a few of my shots in there. There’s one series I’ve been working on forever with girls with their cell phones. And it goes back to before everyone had an iPhone. And during this job yesterday, I shot a couple of shots like that for myself while we were doing the fashion shoot – I always stick some of this stuff in the shot list.

I’m so fascinated by this kind of marriage between the art image and, let’s say, commercial images. Your work perfectly summarises that in a way. You could look at one of your artworks and one of your magazine shoots and maybe no differences would catch your eye, in terms of the involvement of the same compositional methods, sometimes the same subjects.

It’s more doable with today’s fashion and clothes. It is much more relatable and similar to (those of) my art images. I mean, now, when people work with me, they let me keep it much simpler regarding styling. A long time ago, I would be doing these jobs, and they would have these ridiculous clothes, and those photos are pretty useless to me now, but if I can keep it looking really natural with something someone would actually be wearing, then it works for me. The marriage you mentioned might take place. In some jobs they just let me do whatever I want, which is great!

I can do every single kind of shot I’d like to do. And yeah, that’s fun.

And do you have a studio practice?

No, I have a pretty large apartment here in New York, and that used to be a studio. But then I had a kid, got married and a bunch of other things took place in my life. So now it’s more of a living space. But I do break it down into a studio every once in a while. I’m doing that next week. I just move everything around and create a studio in it. So yeah, sometimes I work from home and use it as a location.

And speaking of New York, what do you think about how things changed? Back then there was this kind of huge community around music and art as well. What’s your take on the present?

As far as I know, from talking to my son and some other young models, there’s still a gigantic community of all these different underground scenes that I don’t know of because I don’t go out at night much anymore. But all that stuff still exists. It may have been a bit more grimy or dirty when I was young. New York has gotten much more cleaned up now.

I know it seems a dumb question but how did you find your voice within that community? When did you realise that you were an artist?

I still haven’t realised that. I would call myself a photographer. That way I can avoid anyone saying I’m a bad artist [laughs].

But who cares, right? I was wondering though, during that time, you collaborated a lot with musicians and other artists. Is it something that you’ve lost interest in now? Is it not as exciting anymore?

Well, I still do a lot of that stuff, but I’m not going to do it as much. Certainly, I won’t do it for free! Back then I would just do anything even if there was no money involved. But I don’t really have the time to do that anymore. But there’ve been people who’ve been my assistants or models who want to try something who I collaborate with for fun. An example is this Italian woman, Maria de Stefano, who worked for me for free for a long time and has this big project going on in Italy about migrant teenagers and their stories. She worked with me and then she went off and did her own thing.

A model I worked with when she was young went off to become a hugely successful painter. I helped her turn an idea she had into a short film and shot it for her. This kind of thing has happened a few times and it’s always good for me to see.

What do you think changed in the world of photography throughout the years and how has your practice evolved?

Well, the most obvious changes are digital photography and the iPhone! That pretty much made anybody a photographer now, which is fine with me.

Anyone?

Yeah. What I’d say is that I started when the film was the technology and there weren’t a million photographers. That’s the main difference I’m seeing. And I consider myself lucky to have started when I did and still be doing it. There is one thing I remember from art school. It wasn’t necessarily told to me, but I realised that whatever you start doing, you have to never stop. You have to do it all the time. There are the Sunday afternoon photographers or the Sunday painters who do it in their spare time as a hobby…but whatever you’re doing, you just have to keep doing it. I’ve seen a lot of people fall by the wayside over the years but I don’t know why I keep doing it. I just keep doing what I’ve always done I guess because it’s fun for me.

Since we’re talking about continuity, what’s the next project you’re working on?

I have three or four books coming out pretty soon. One is a book of Polaroids I took as test shots. That’s called ‘Polaroids’. Another one contains black and white photos from 1980 to 2005 that have never been published. It’s called ‘Gray’. ‘Cops’ is a fanzine companion to a zine I did two years ago called ‘Cars’. It’s photos of cops in NYC in the 1970s and 80s. And there’s another one called ‘Incorrect’, a collection of photographs of people holding grey cards. Before the current cameras, you had to hold up a grey card at the beginning of every shot, so that you could make sure you got the colour right. People aren’t posing, they’re just standing there or whatever, and none of the photos have been retouched or corrected, so it’s a book of messed-up photographs.

That’s amazing! Books are of course a core part of your practice. You’ve done tons of books, and many of them have legendary status. What is your approach when you start a new book? Like, how do you work on that? Do you have a specific process for editing down images, what defines for you the bookmaking practice?

Well, it takes forever. In the past, when I was doing books like ‘New York Girls’, I’d do those with Taschen. And they were specifically interested in photographs of naked girls. That’s what they wanted and for a long period, that’s all I was doing.

But those big publishers don’t do that kind of book anymore. It’s completely unprofitable for them now because of the internet. So the books I’ve done the last few years have all been with a small press because they let me just pick a topic, make me a book, and then publish it. An example of that, and probably the best example is the book ‘Medicated’.

I shot girls who were on medication for about five years. At the same time, I interviewed them about the medications they were on. Those interviews are the text that accompanies the photos in the book. Books where I get to do a specific topic, are the best thing for me. I backed off on shooting nude because it’s a lot easier to get stuff published.

I have Cars which I love, by the way.

Oh, you like that book? Yeah, that’s a nice one. The cop book is the companion of that one. Same format and everything, same time period.

But I was gonna say also when I’m shooting people with their clothes on, they still look just as sexy as without their clothes. More provocative, I guess provocative is the word I’m looking for.

One thing that gets me thinking [regarding nudes and representation] is Instagram. Everything is a minefield there. Everything has to be carefully thought out because you get attacked by this group or that group or whatever. And that’s why I like to do books because no one can attack you directly. [laughs]

I haven’t thought about it before, but I’m just realising now that your images have, in a way, transitioned in use-value. Back then, porn movies and online porn weren’t aligned, and there was less circulation. So your images were treated as pornography by publishers, you mentioned Taschen and their interest, and users as well.

I shot real pornography at one time, so I can totally understand that.

But today, maybe, since there’s so much porn online, and things have gotten much more hardcore, those images have transitioned as acceptable in a way, sexy, to quote you, or provocative, but not pornographic. Does that make sense?

Well, also, when an image gets about 20 years old, it no longer is seen as pornographic. Really, I mean, unless it’s hardcore, then it’s going to always be pornographic. But at about the 20-year mark, they just become nostalgic, people look at it in a completely different way. When I first showed ‘New York Girls’ photographs, it upset a lot of people. Art critics mainly but they’re easily unsettable. But now, the same kind of people look at those photographs with affection because they had seen them in their youth. Another good example of that is the movie ‘Fingered’, which caused so much controversy when I made it in ’86. Wherever it was shown there was always a problem! Now it’s in the MoMa collection! That kind of stuff happens all the time.

“Think about ‘Un Chien Andalou’, people ran out of the theatre screaming when it was first screened and now it’s an art classic.”

Every invention had this kind of shock value at its inception. Science, religion, art: everything that breaks up a determined pattern meets some resistance. But I also understand you perfectly when you’re talking about the nostalgia effect. What do you think about the duration of an image? You basically said it, but I wanted to see if you had more. Can images transform throughout their own life and maybe tell different stories?

A good example is something I put on Instagram recently, two girls from Smith College laying on a bed – a couple. They look pretty punk. It was from 2004. A young journalist had written to me asking if I knew this image was all over the place in the gay and lesbian culture. I wasn’t aware of that. He said that image was everywhere and he was writing his thesis on it. I put it on Instagram, and then another friend of mine who’s 25 told me it was everywhere on Tumblr, and that it had been there forever. So that way, I found out that it was an iconic image.

What’s your relationship with galleries and shows, at the moment?

I just had a show in Switzerland. And that was the first one I’ve had in a long time. They wanted to show very old photographs, [laughs] which is fine. The photos were from 35 years ago so any kind of controversy attached to them has been removed. But I think because of wokeness, many galleries I used to work with are really paranoid about working with somebody like me now, but maybe not. I don’t really know.

I can see what you mean. I think there are some huge structural problems with cancel culture and the art world right now, most people are maybe scared to show works that are controversial, like maybe yours.

Even if the work shown per se isn’t controversial, it doesn’t matter, they look at your whole past now. That’s where the controversy comes in. But it seems to have turned around quite a bit. It’s almost as if wokeness became kind of uncool. And there’s a reaction to it.

“Every scene eventually provokes an opposite reaction!”

Credits

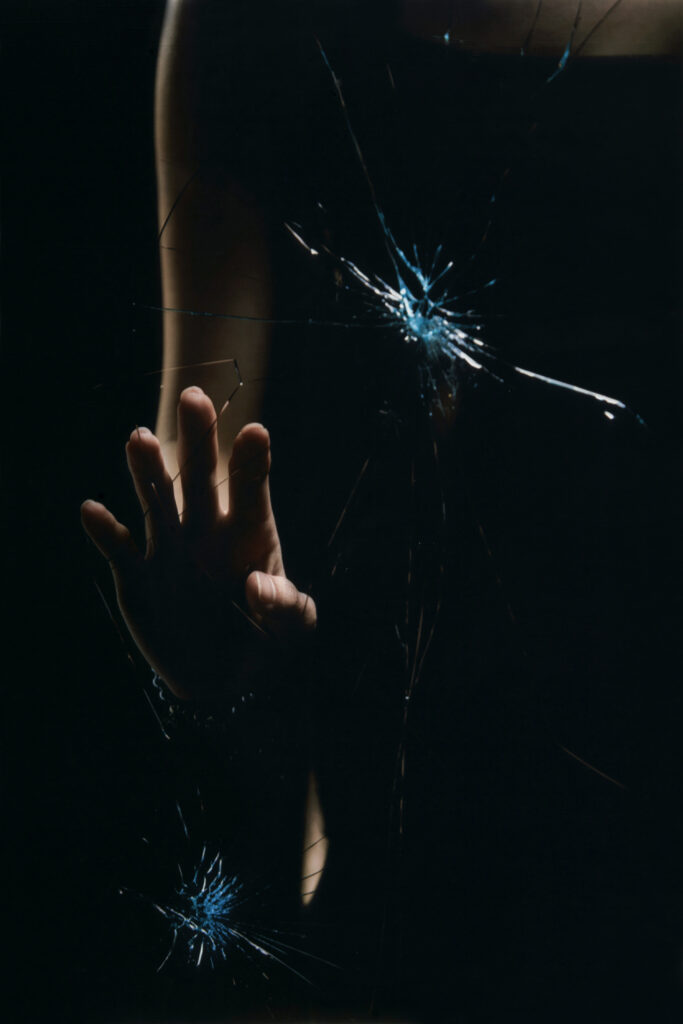

- Cristina with Guns, 1990

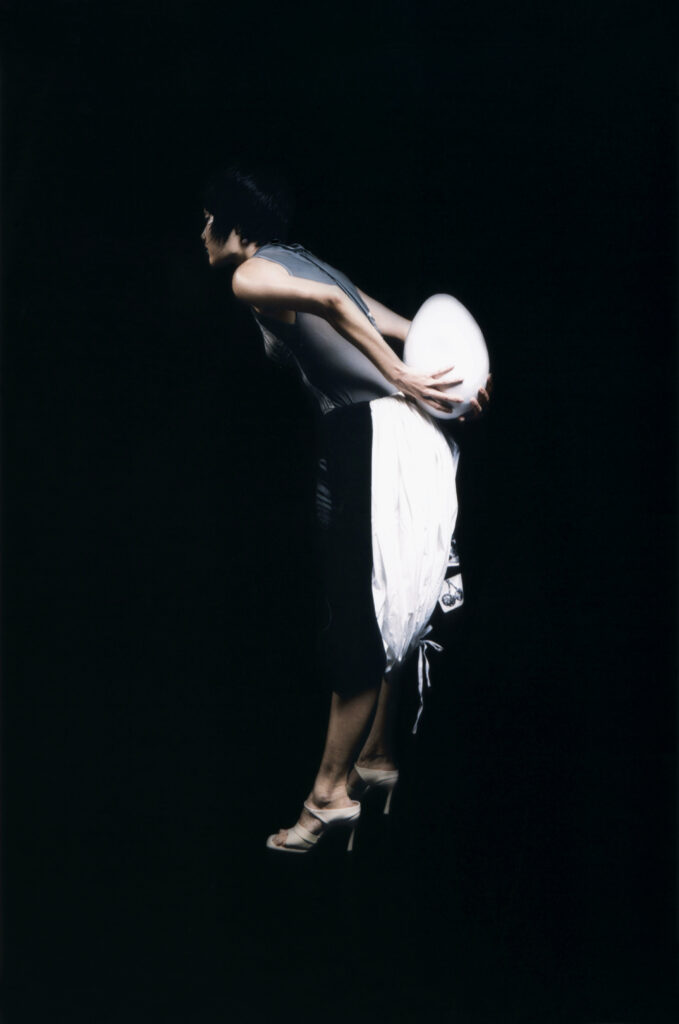

One of the first series I did was women with guns. I had a slightly paranoid friend who supplied all the guns for the shoots. Shot in my living room in NYC. - Toni Garn for Numero Berlin, 2016

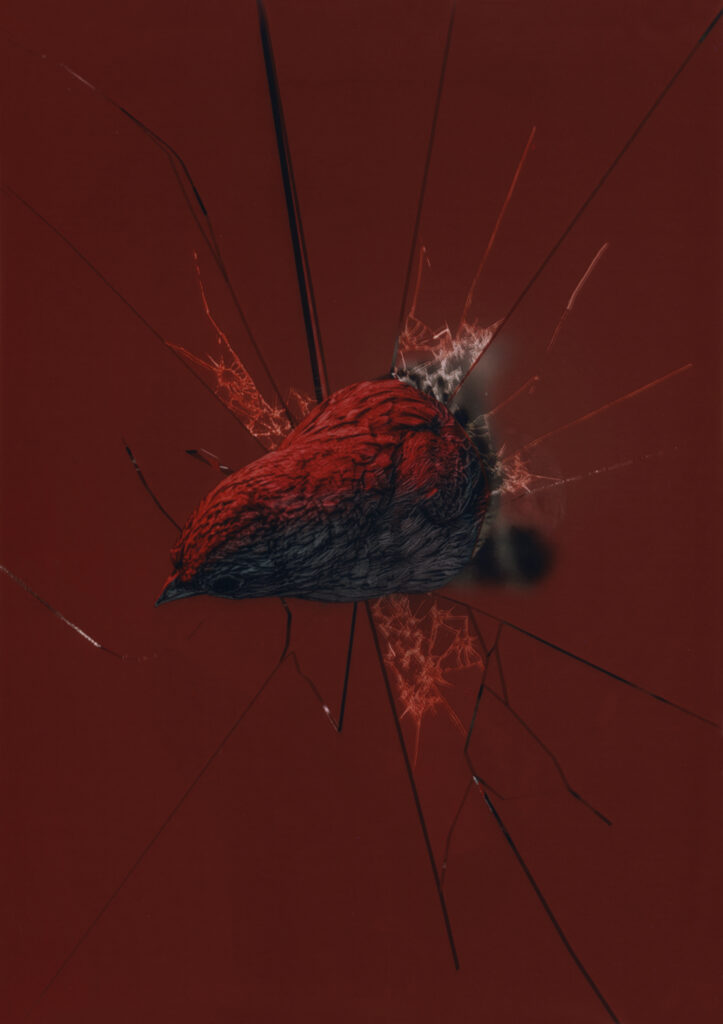

This shoot was a cover shoot for the first issue of Numero Berlin. - Lung Leg’s shirt, 1987 (note I had the wrong date on the file I sent).

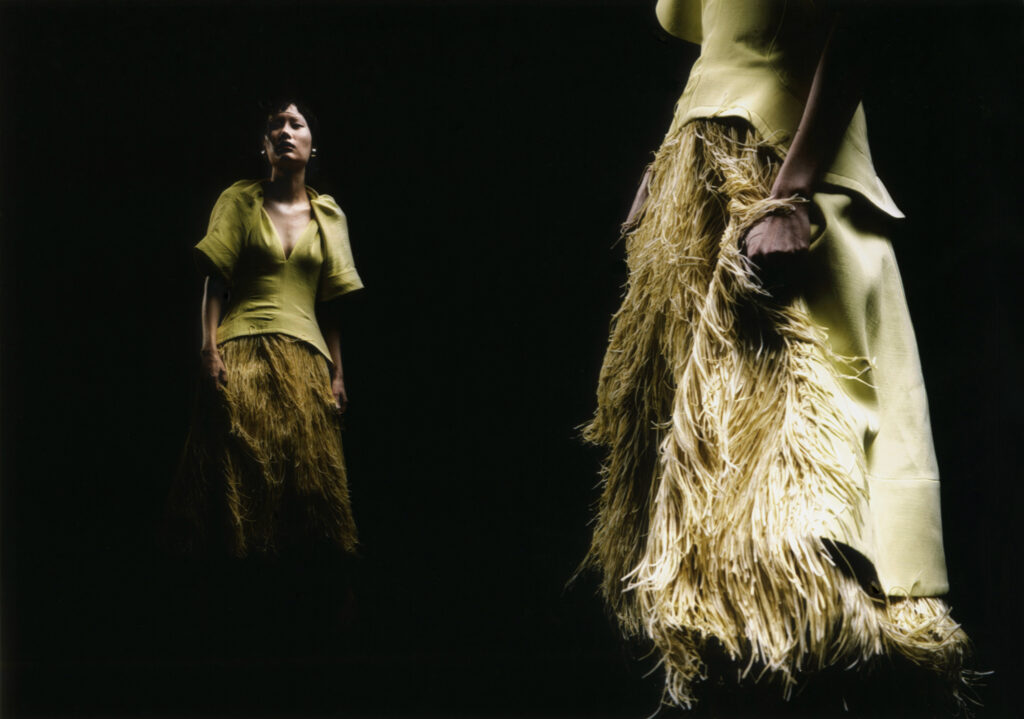

Lung Leg was the focus of many of the films I made in the 1980’s including You Killed Me First 1985 and Fingered 1986. Lung is an excellent painter. Back then she was obsessed with Demons and this shirt shows one of them. She made several Demon short films in the 90’s. Now she paints animals and does commissions for private collectors. - Hunters, 2006

Shot in upstate NY with my ex-wife (in the orange) and a model from Chicago. A friend in upstate NY offered to let me shoot on backcountry farmland he owned where he secretly grew marijauna. He supplied the guns. - Julia in her bedroom, 2017

Julia Fox in the NYC apartment she was living in back in 2017. - Kemp from GQ Italia, 2008

Model Charlotte Kemp Muhl shot in her NYC apartment. For 2-3 years I was shooting women for GQ Italia. - Test polaroid, 2003.

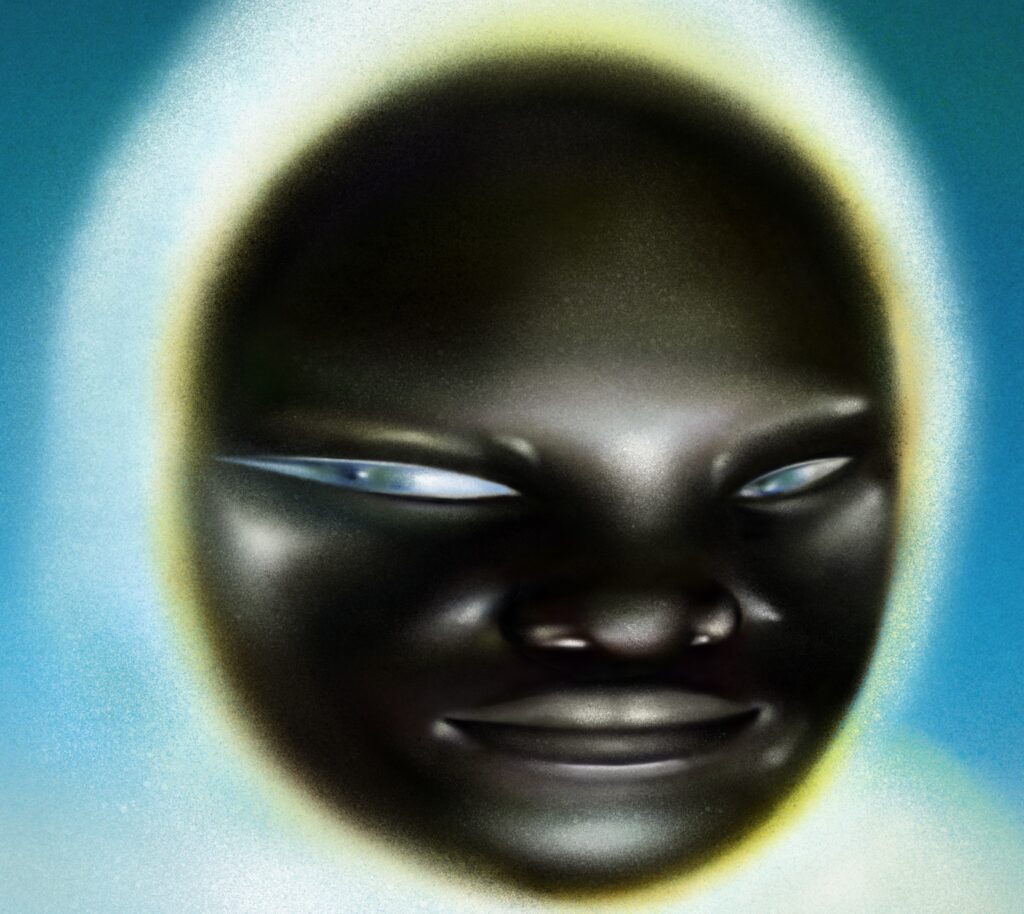

This was a test shot for an early shoot I did for Double magazine and as often was the case, the polaroid was better than the shots I took. - Naproxen, Serteraline, etc, 2016.

One project I focused on for many years concerned young people taking doctor’s prescribed drugs. The result was the short film Medicated (2013)(which can be seen on my website) and the book Medicated published in 2021. - Hand in mouth, 2000

I was shooting this girl for a “leg” magazine in Los Angeles when she said “I can put my whole hand in my mouth” so of course i said “let’s shoot that”. - Smith College Couple, 2004.

A friend attending Smith College suggested that I come shoot and interview some of the students there as it was known as a lesbian friendly environment. She offered to cast. I pitched the story to ID Magazine.

All works courtesy of Richard Kern.