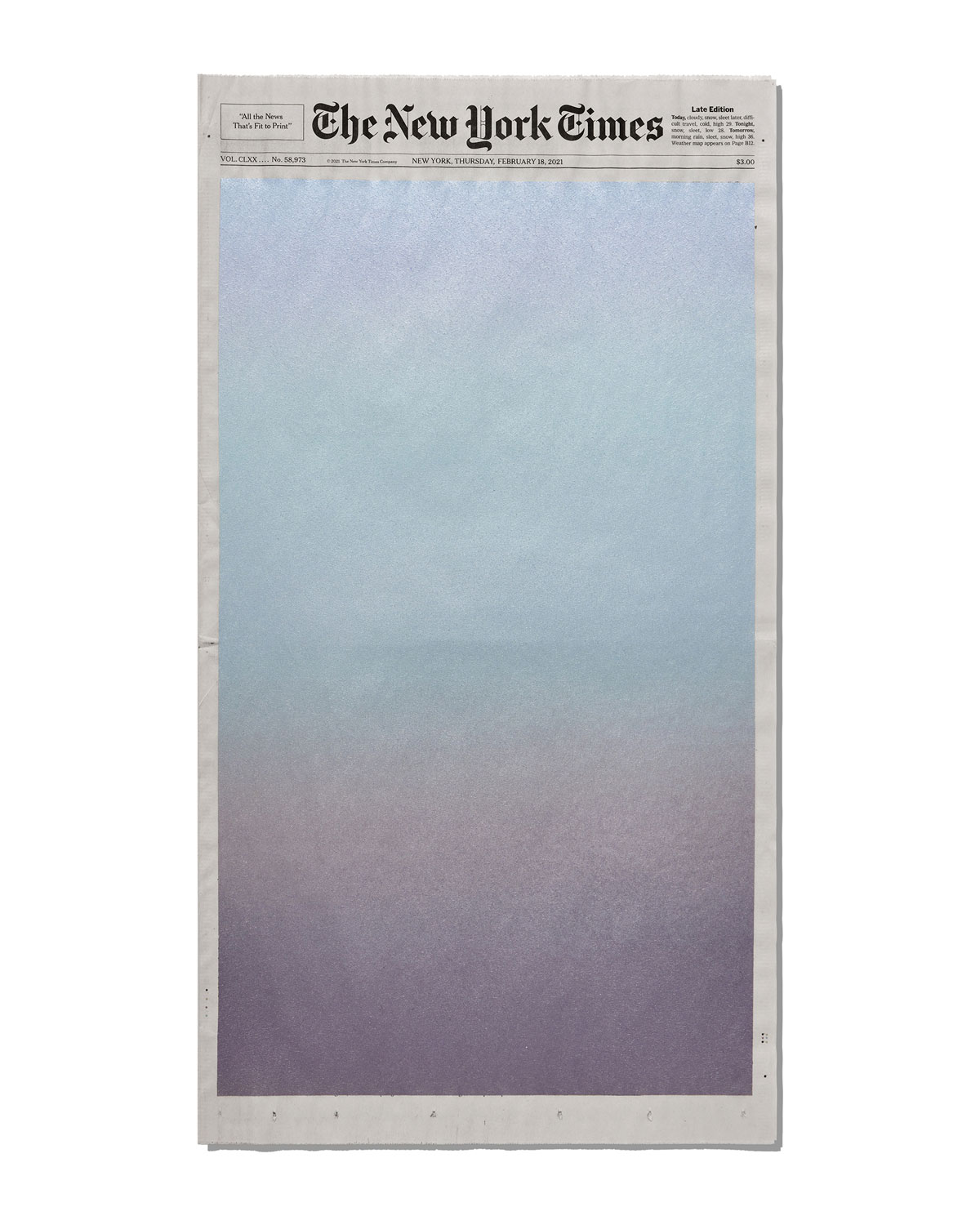

“I just so happened to want to capture the contrast of the beautiful sky against the ominous news.”

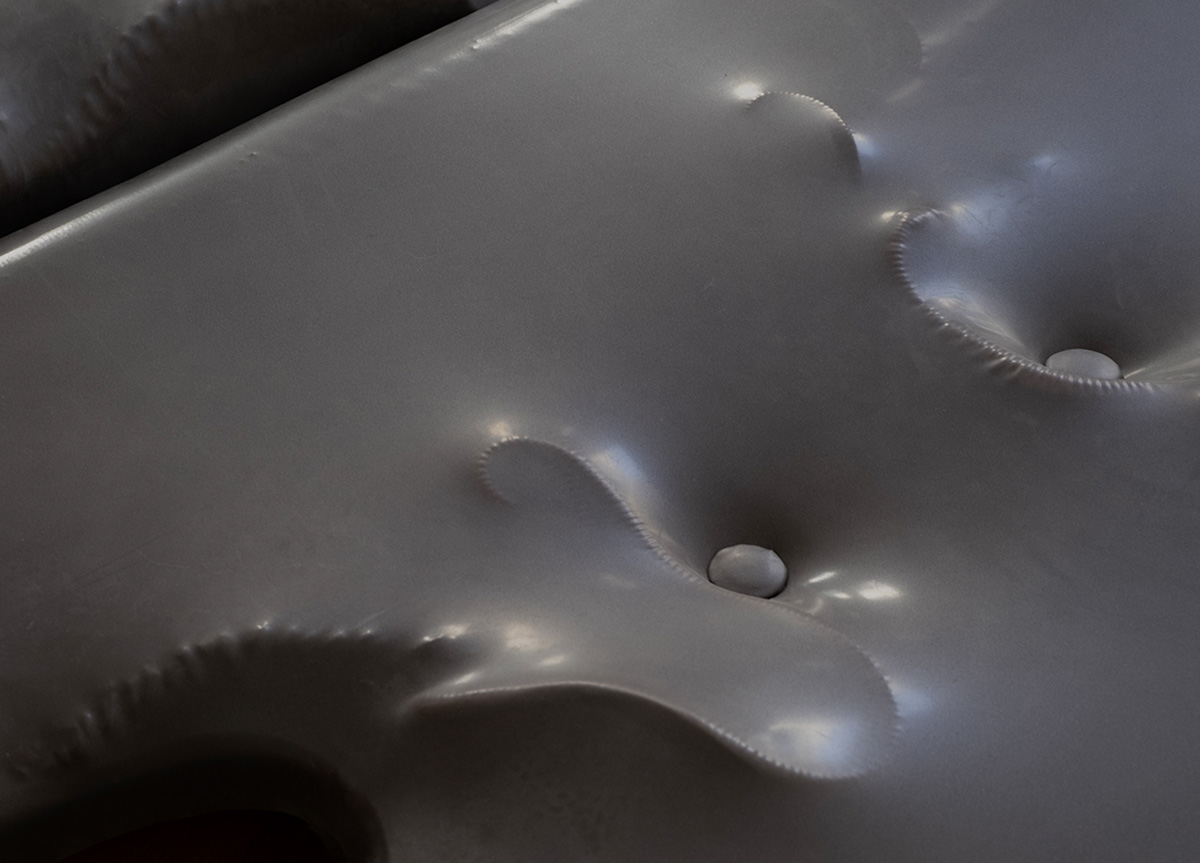

Sho Shibuya is a graphic designer who has lived in New York for the past ten years – the last five of those years spent painting every day. Originally from Tokyo, Shibuya’s move to the Big Apple gave rise to a fascination with the city and the elements of design that are distinctively “New York”. In fact, something the designer was quickly struck by was the number of plastic bags that littered the city’s streets – is there anything more “New York” iconic than the “Thank You” plastic bag? Shibuya began collecting abandoned bags which were the subject of a book from 2019, Plastic Paper. If the project was a celebration of the city’s rich visual identity, as captured in plastic bags, it was also designed as to provoke a necessary conversation about the environmental hazards caused by single-use plastic. The bags were banned state-wide on 1st March 2020, though a loophole meant that retailers serving food can still these bags. Nonetheless, Shibuya’s bag collection was featured in a New York Times article the day before the ban.

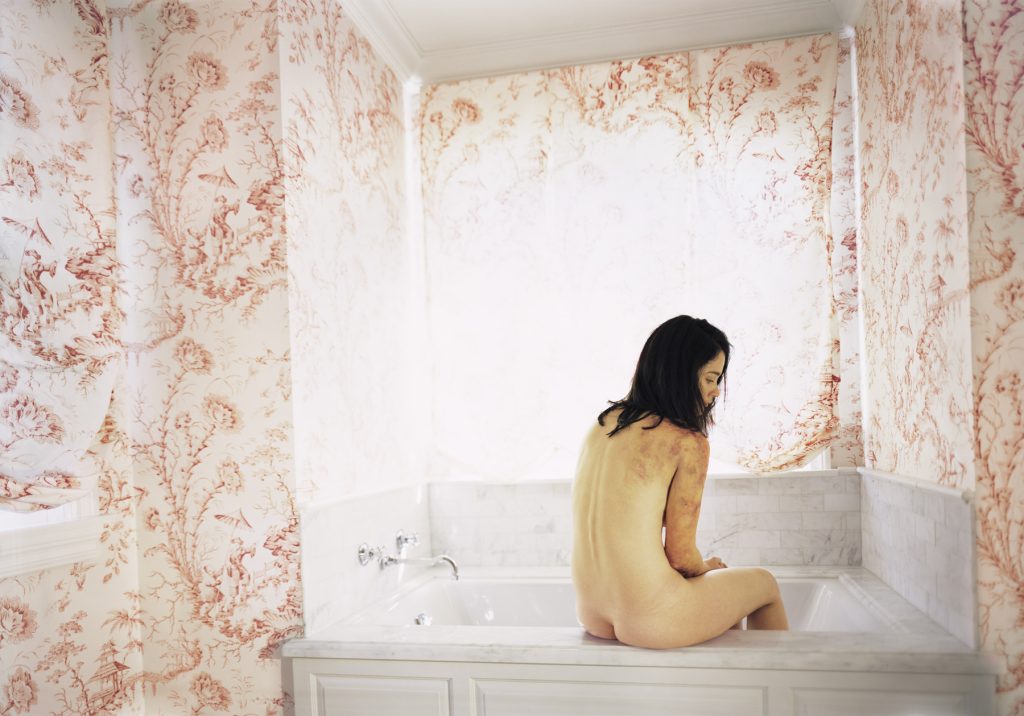

Fast forward to late May that year – with the city slowly emerging from lockdown following the first COVID wave – and Shibuya’s work appeared on the pages of the New York Times once more. This time, however, it was the designer sharing a photograph of a full-page painting over the newspaper’s cover on Instagram. Shibuya depicted a sunrise gradating from white to deep blue on the day that the Times paid tribute to the almost-100,000 deaths to COVID in the United States at that moment in time. This was Shibuya’s first full-page painting on (or over?) the cover of the New York Times, and it captures the way in which the designer (and painter) strives to “really understand [an] event and show respect to any cause.” There was some criticism to that initial post – that in painting over the names, it was glossing over the scale of pandemic’s impact – but as the subsequent paintings reveal, Shibuya’s creative interpretations of that day’s news, whether poignant or funny, emotional or thought-provoking, have come to attract an appreciative, warm response from a growing Instagram audience.

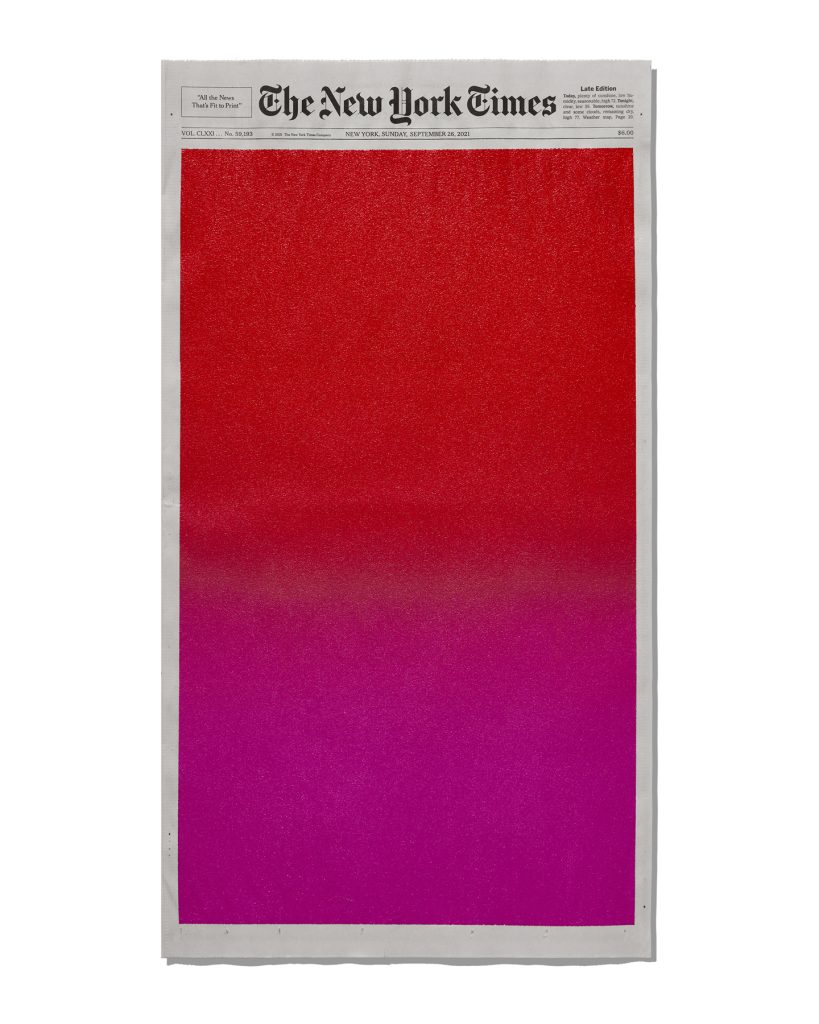

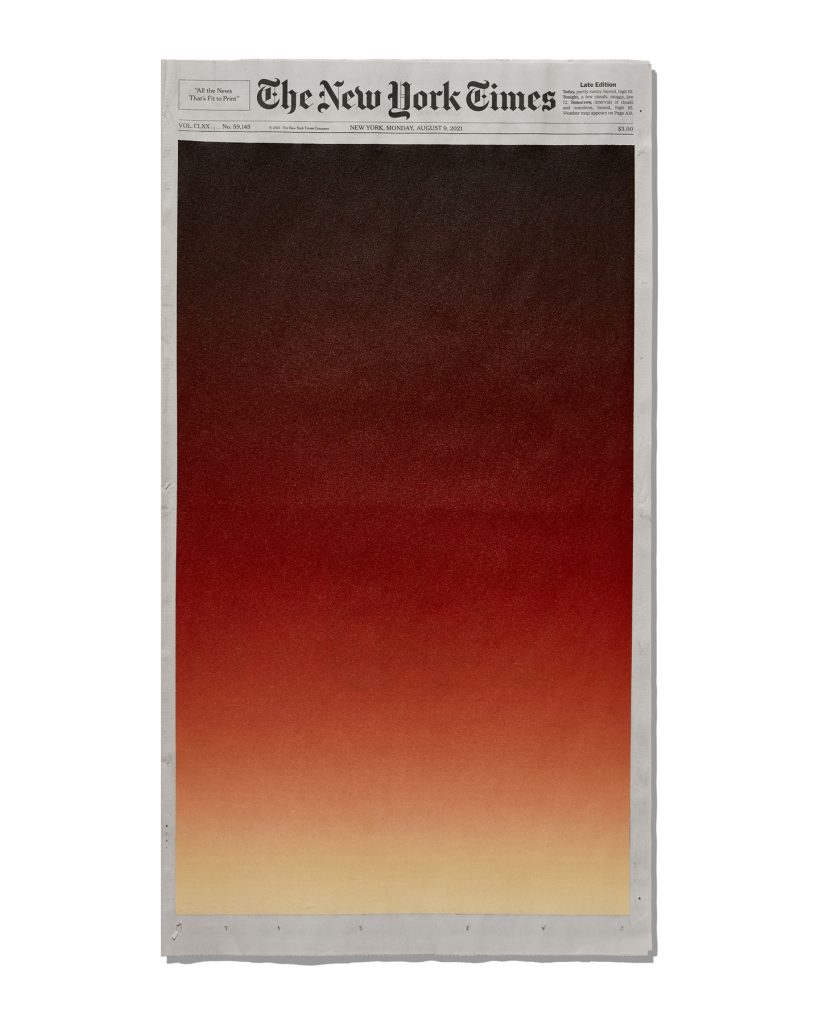

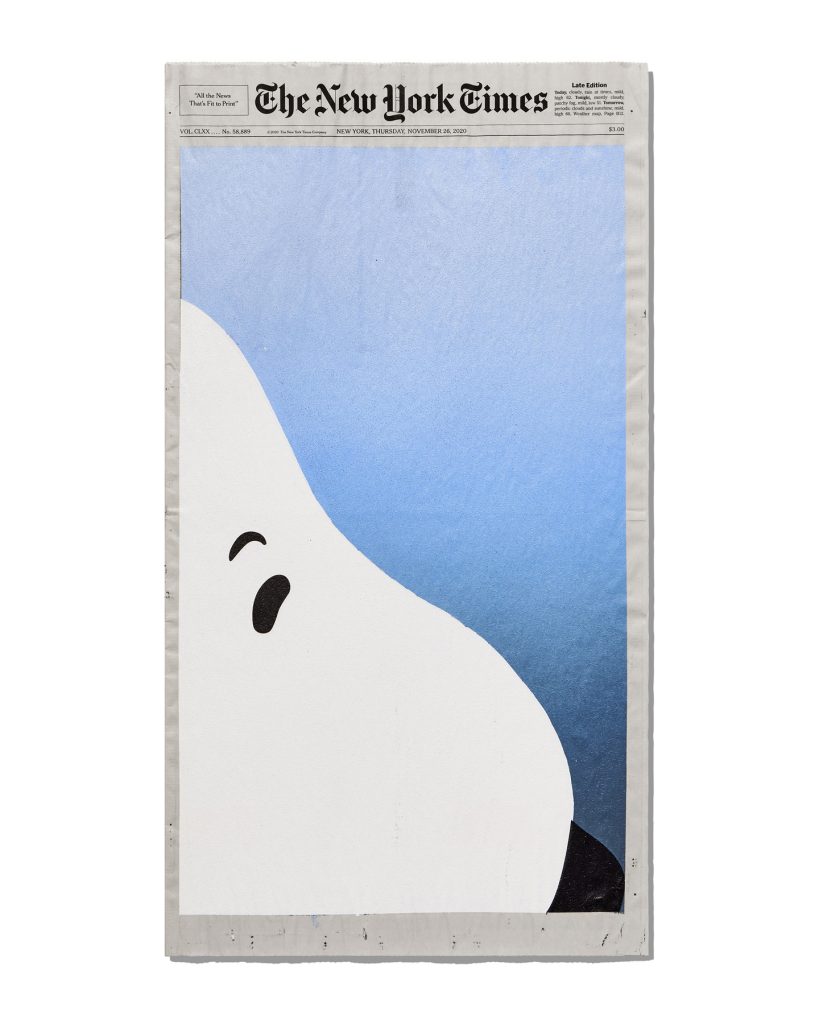

By using the daily New York Times as his canvas, Shibuya paintings move between reportage of local, American and international affairs – from painting the giant Snoopy inflatable from the 1988 Macy’s parade on Thanksgiving, the diagonal lines synonymous with OFF WHITE in honour of Virgil Abloh’s death, a collaboration with Patti Smith urging Americans to vote in the 2020 election, to painting scenes from the floods and forest fires that gripped the world last summer. If Shibuya began by painting the sunrise each day from his window during the lockdown, his paintings have become an entryway into a wider celebration of the little things we can be hopeful about. Each day, no matter what, the sun rises – and the news, no matter how difficult it may be, continues. And amongst that, Shibuya’s paintings give us a moment of pause and reflection.

NR: You started sharing Sunrise Through a Small Window on Instagram during the first American lockdown in 2020; were you expecting the kind of response you have had since then?

SS: Not at all. Painting has been part of my daily ritual for over five years. It just so happened that this series seemed to strike a chord in people. I appreciate the response; it makes me feel connected to the world through my work.

NR: What was it like being commissioned to paint two new sunrise scenes and exhibit a further 53 of your newspaper paintings in collaboration with Saint Laurent at last year’s Art Basel Miami for the 55 Sunrises show?

SS: I visited the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Marrakesh, Morocco, back in 2018. I was fascinated by the whole experience there. Three years later, the collaboration started, and I am grateful for the opportunity. It was my first time in Miami. The idea for the location came from [Saint Laurent creative director] Anthony Vaccarello; I never expected the show to be held on the beach. I thought, it’s a wild idea that you will be able to look back and experience the sunrises and the turmoil of 2020 and 2021. Then, after you are finished looking at the painted sunrises, you can see the real sunrise on the ocean outside.

“It’s like a time capsule, or like a pathway from past to present, and perhaps a future, because I believe the sunrise carries with it some bit of hope or optimism for the future.”

NR: The New York Times paintings are quite different to your book Plastic Paper and the creative platform associated with it. How, in different ways, do both relate to the experience of living in New York?

SS: The objects at the centre of each work, the designs on the plastic bags and the New York Times newspaper, are both everyday objects in New York. From a foreigner’s view, I treat them differently. For instance, if someone took a trip to Japan, they would probably notice cultural significance in mundane objects, like Japanese typography on a sign or Pachinko store, etc. The everyday objects feel fresh to me. That emotion made me use it as a canvas.

NR: Do you have an idea of which painted New York Times covers, news or events might resonate with your audience?

SS: Each piece has different reactions. For instance, the inflation piece that visually explains “no more 99 cent pizza” might resonate with people in New York. In another article, I depicted the tragedy of the wildfires in Greece, and I received a lot of comments from Greece. If the events somehow relate to how people feel or what they’re thinking about, they respond. It’s a natural reaction.

NR: Some of your newspaper paintings (like Rudy Giuliani’s melting hair dye) are quite playful, whilst others are more poignant, how do you decide what kind of approach you’ll take with the paintings?

SS: I never plan what to paint. It is always spontaneous.

“I always start after reading an article, and if something lingers in my mind afterward, I paint that feeling or thought so I can speak up in a visual way.”

NR: What was it about the cover of the New York Times that lent itself to being the canvas for your sunrise paintings in the first place?

SS: I think it was a bit of chance. I always read the New York Times every morning, and when I made the very first painting, I just so happened to want to capture the contrast of the beautiful sky against the ominous news.

NR: Of all the New York Times paintings you’ve shared on Instagram, which one means the most to you? And which have people most engaged with?

SS: The first full-page painting: May 24, 2020. The New York Times cover paid homage to the 100,000 people who had died from COVID. I was really emotional painting that one and still remember every moment of when I was painting it. The most engaged one was when I painted the Palestinian flag on the cover. I agree when Haruki Murakami said, “between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks it, I will always stand on the side of the egg.”

Credits

Images · Sho Shibuya

https://www.instagram.com/shoshibuya/