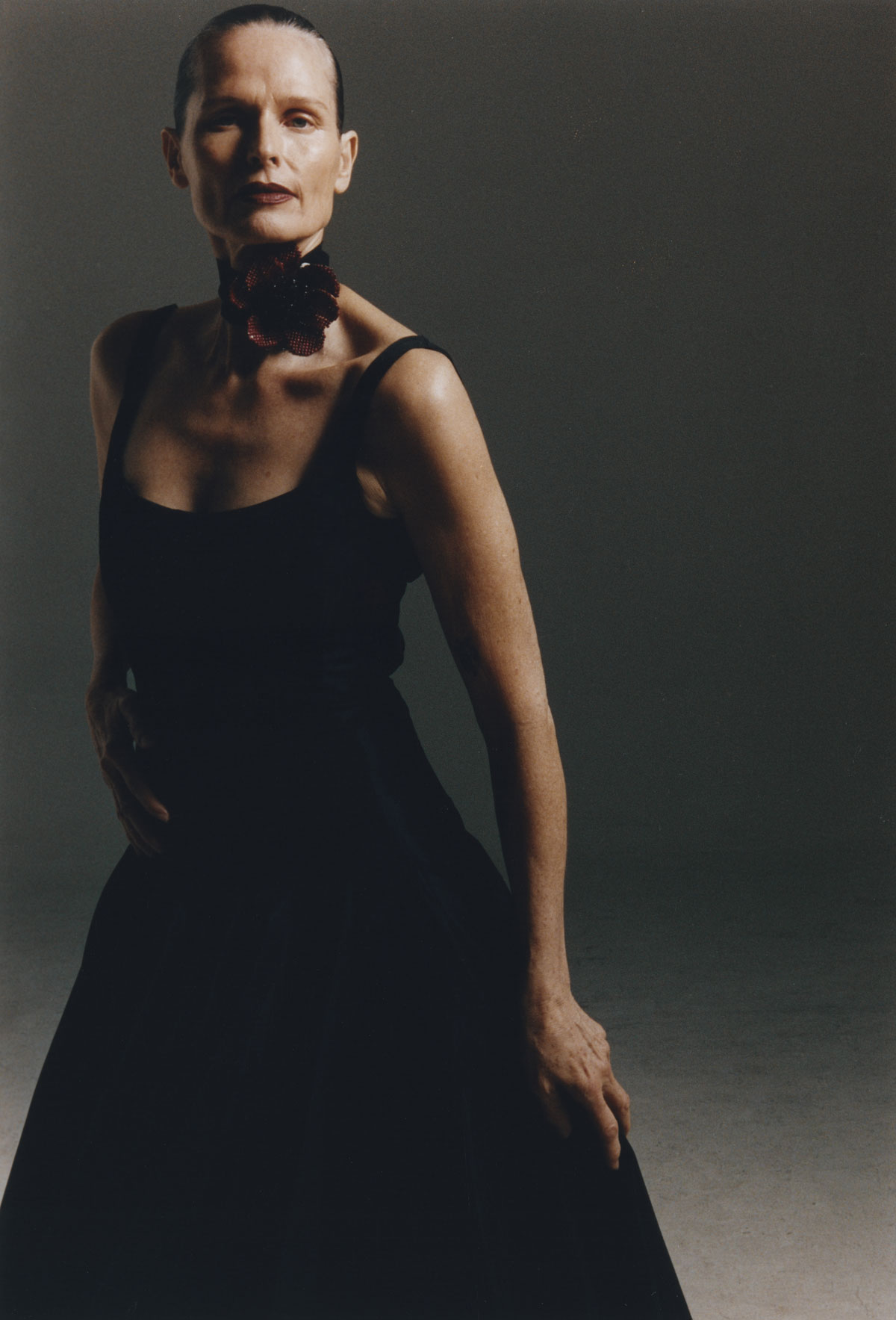

“every day is a plus – to wake up and be healthy, and to find myself in this unique position”

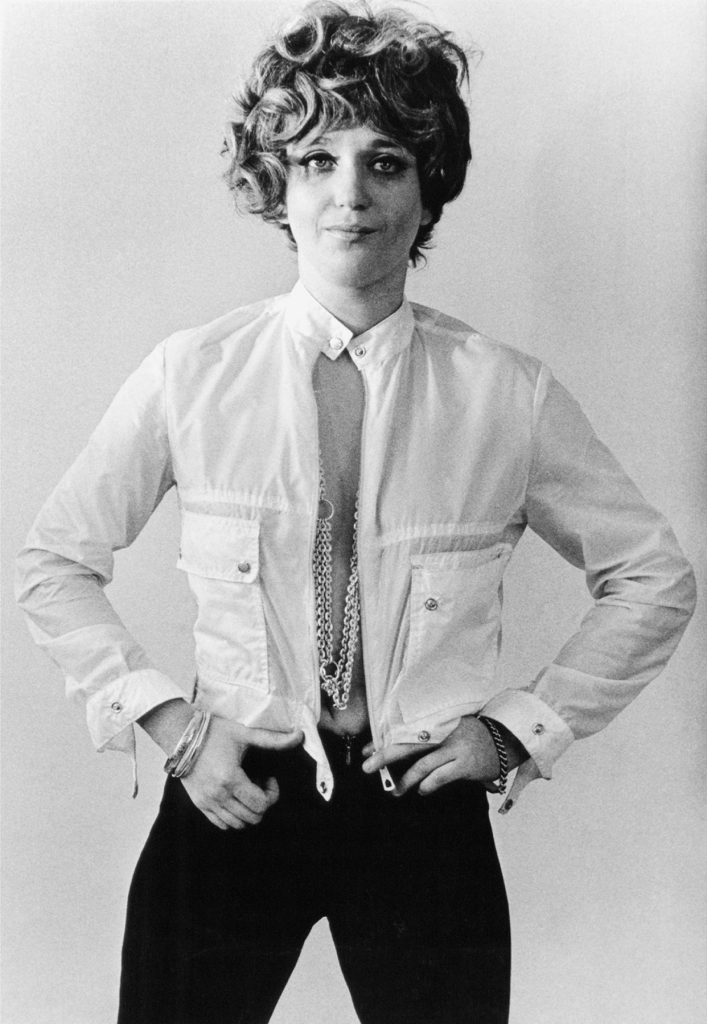

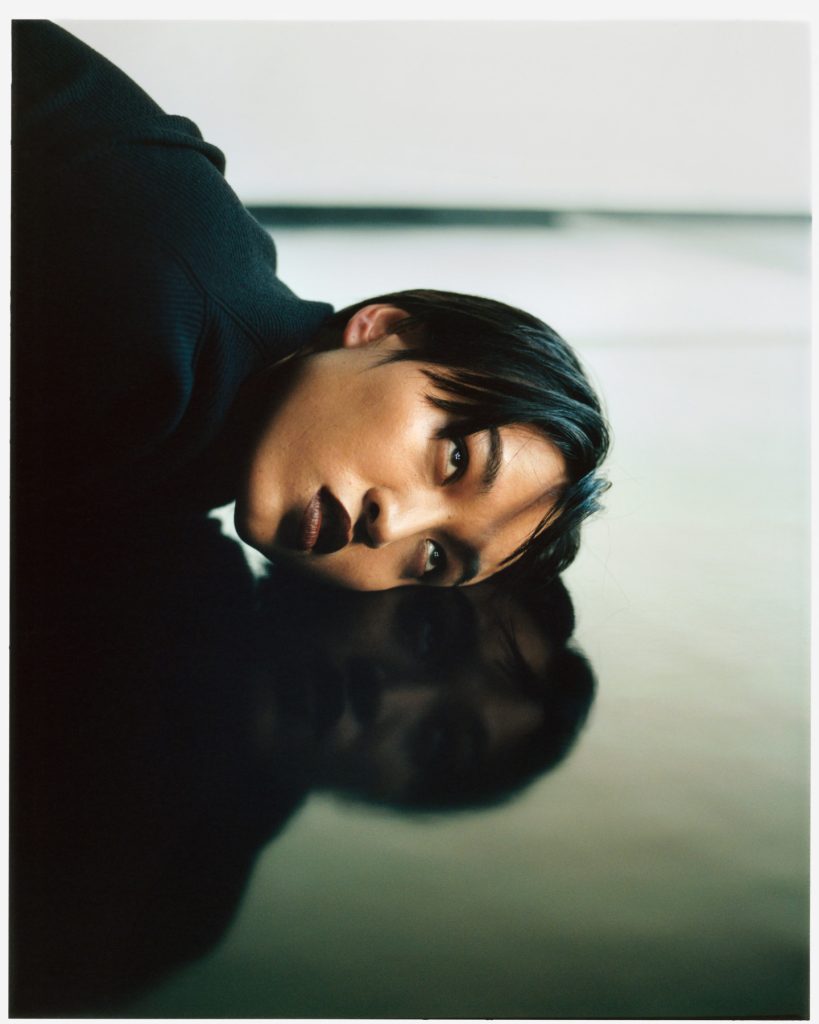

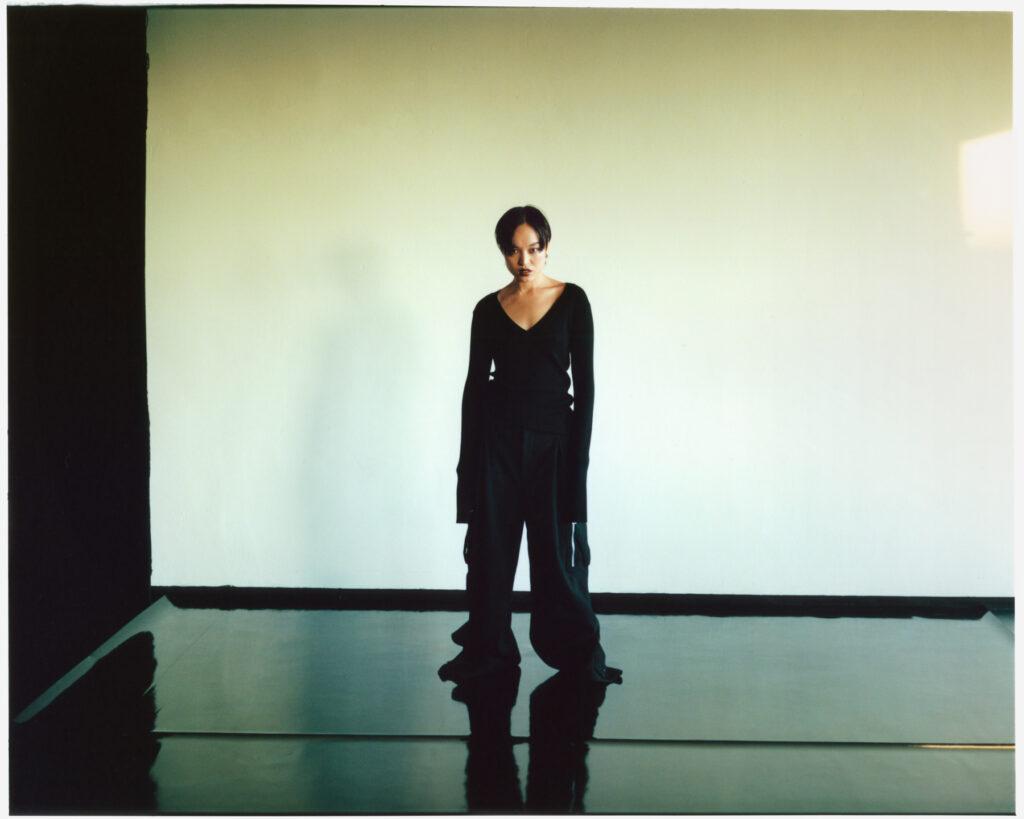

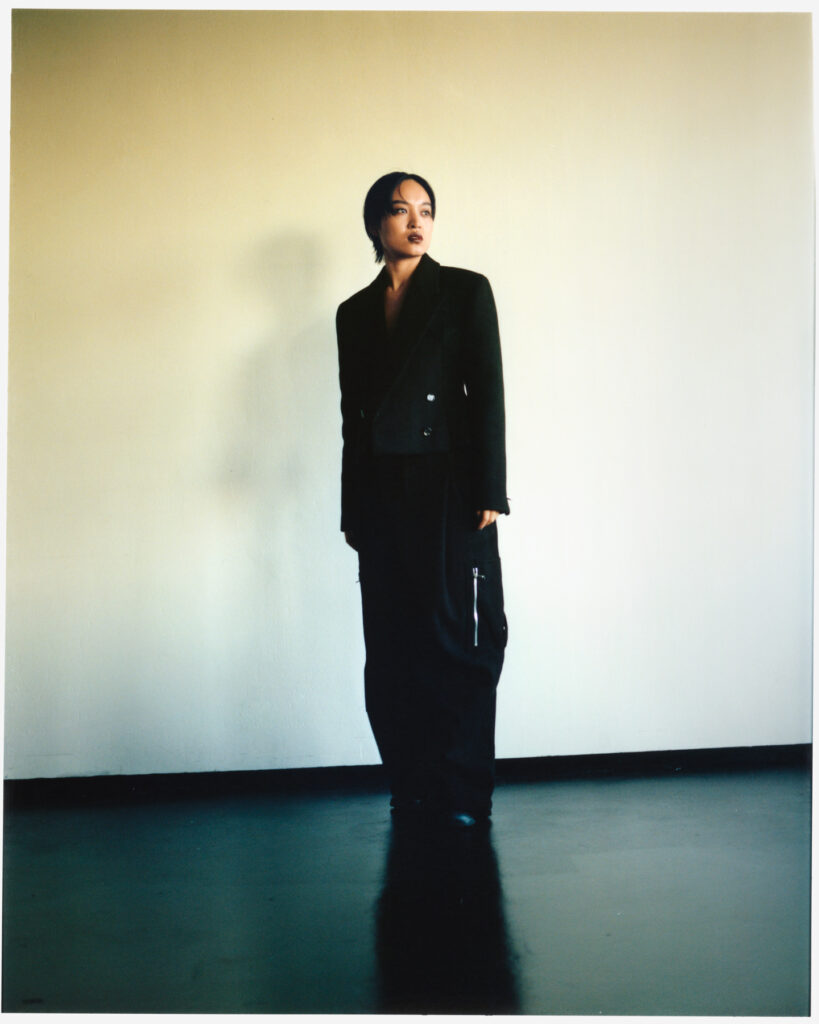

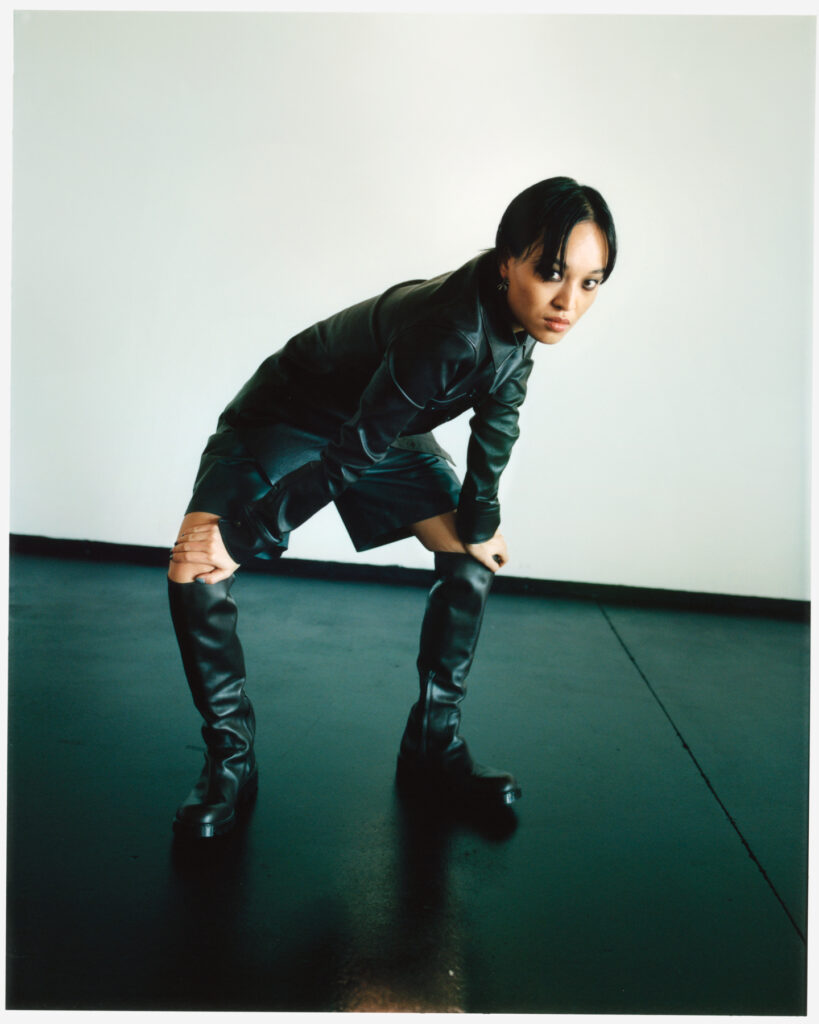

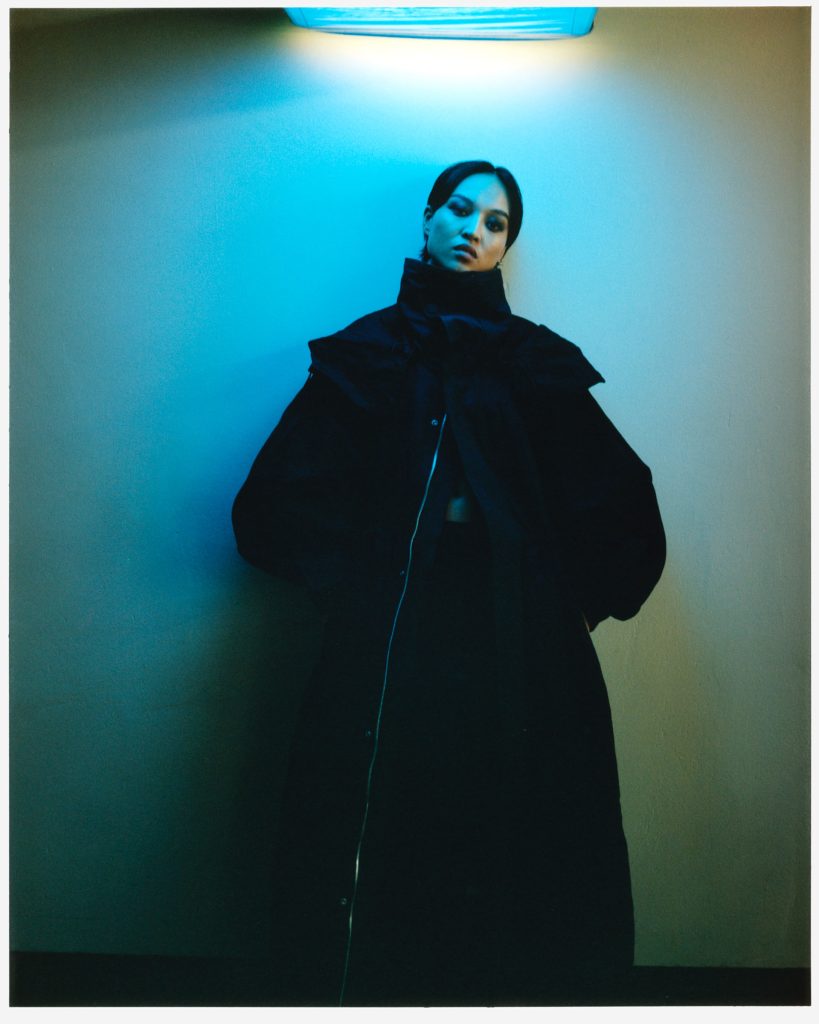

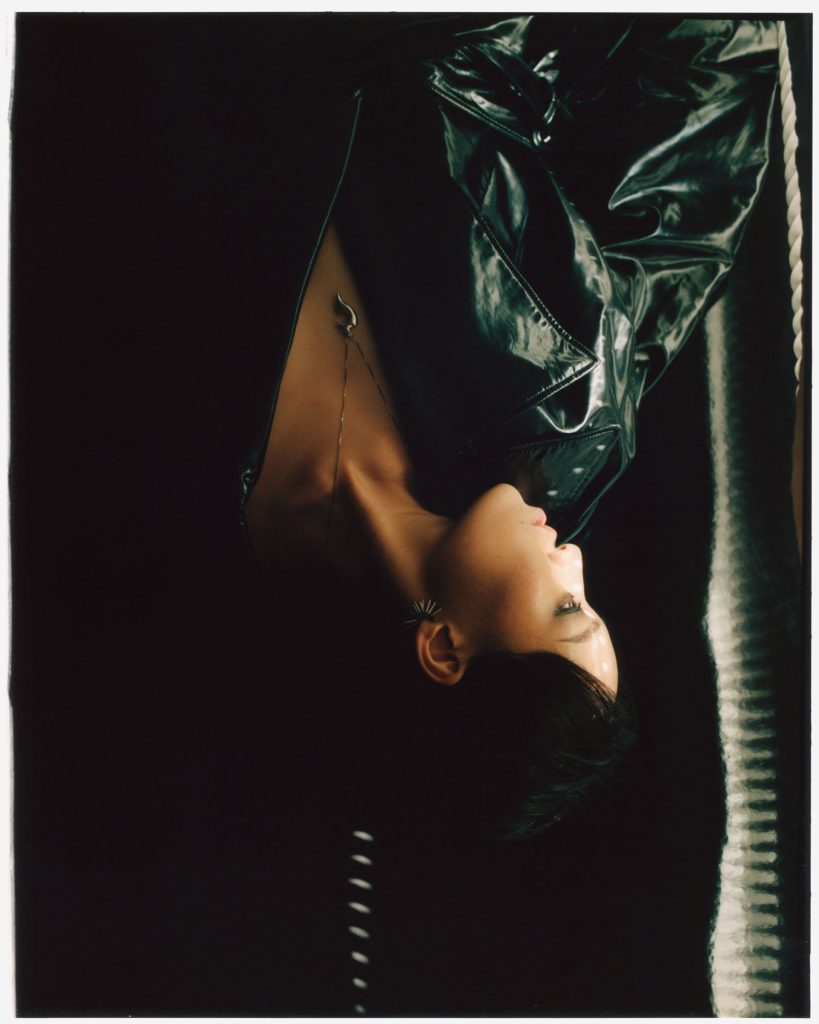

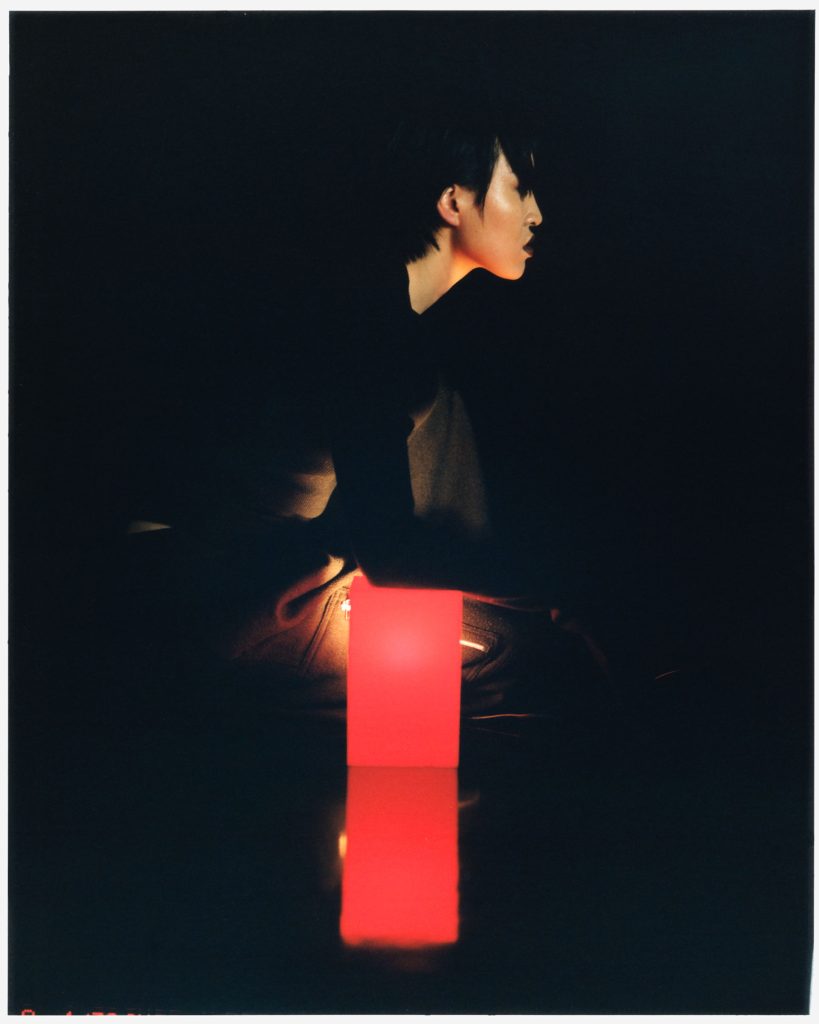

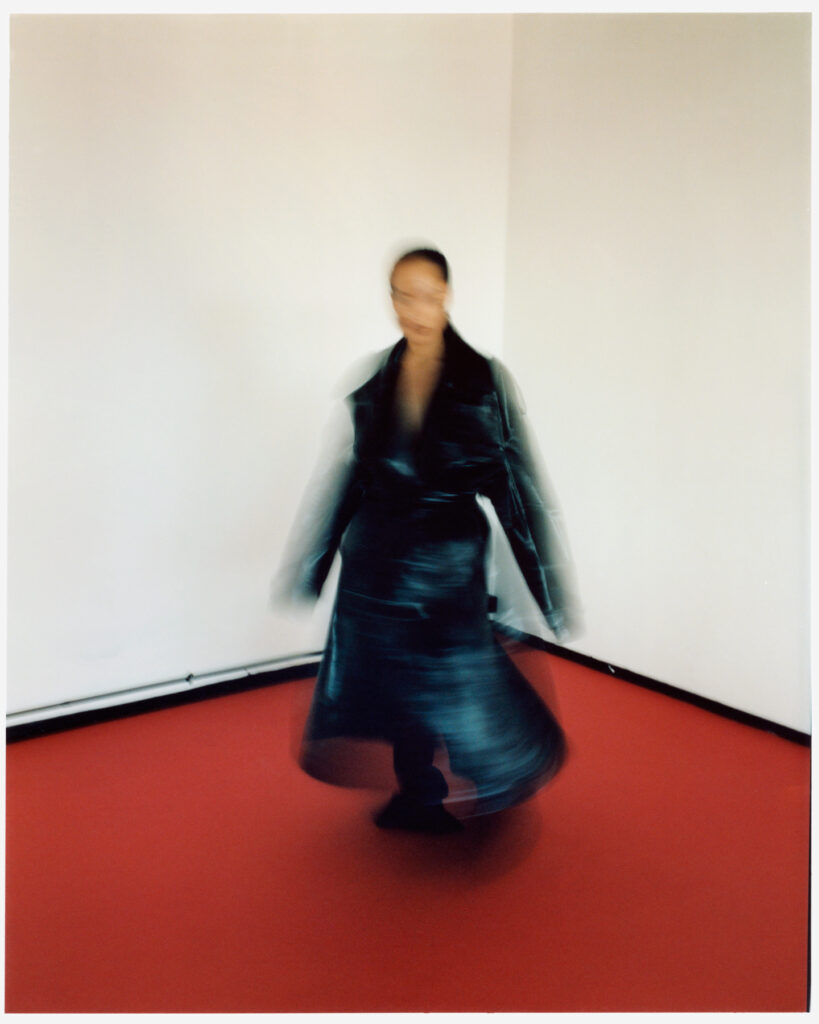

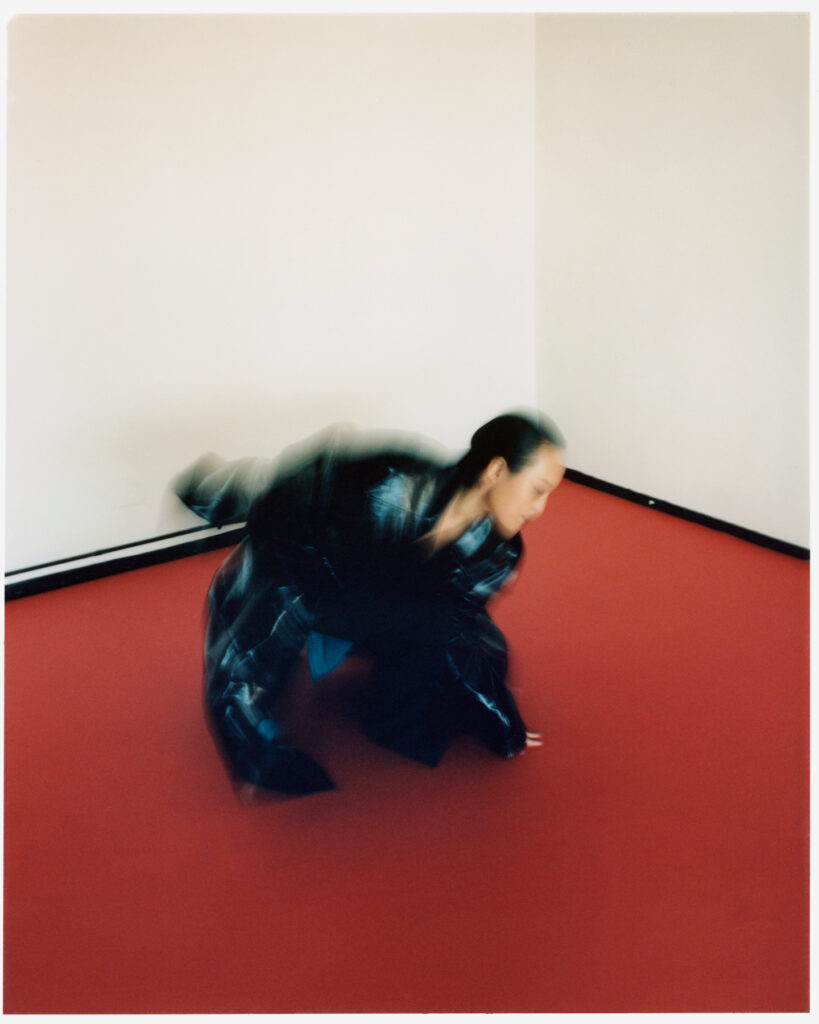

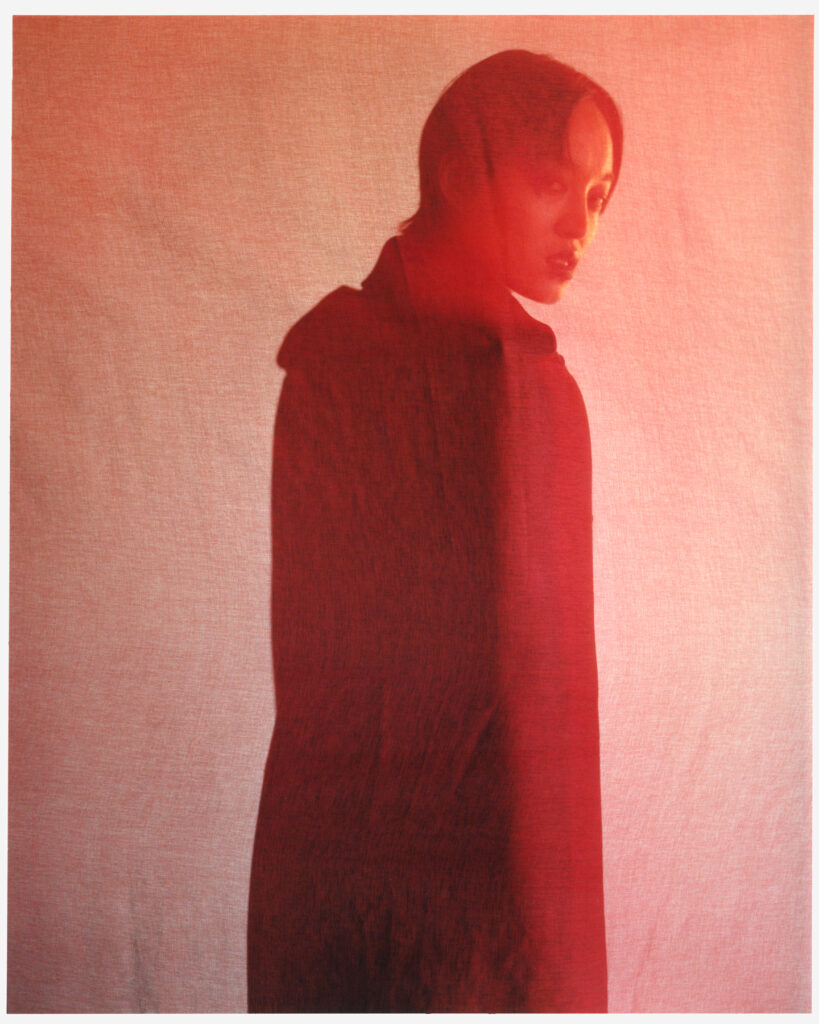

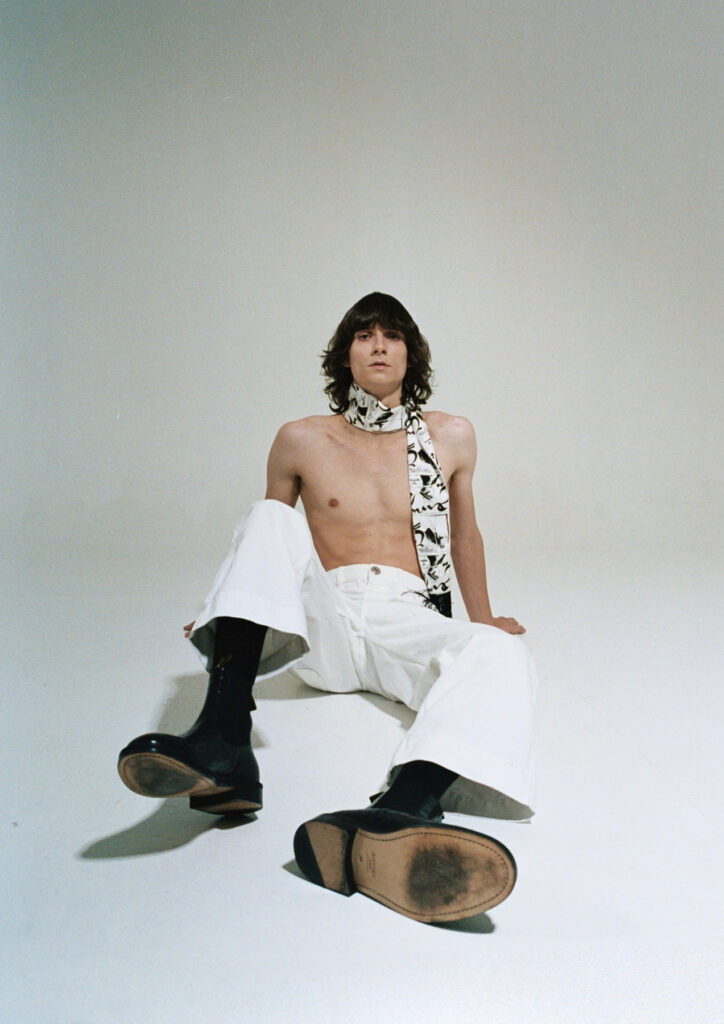

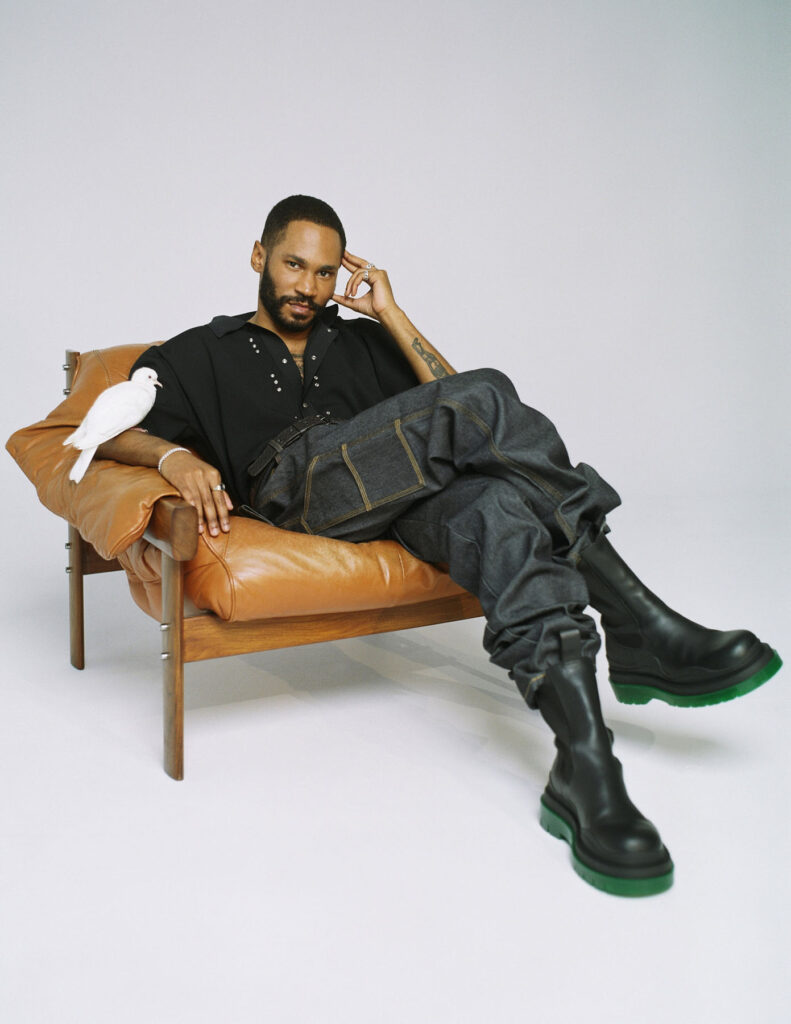

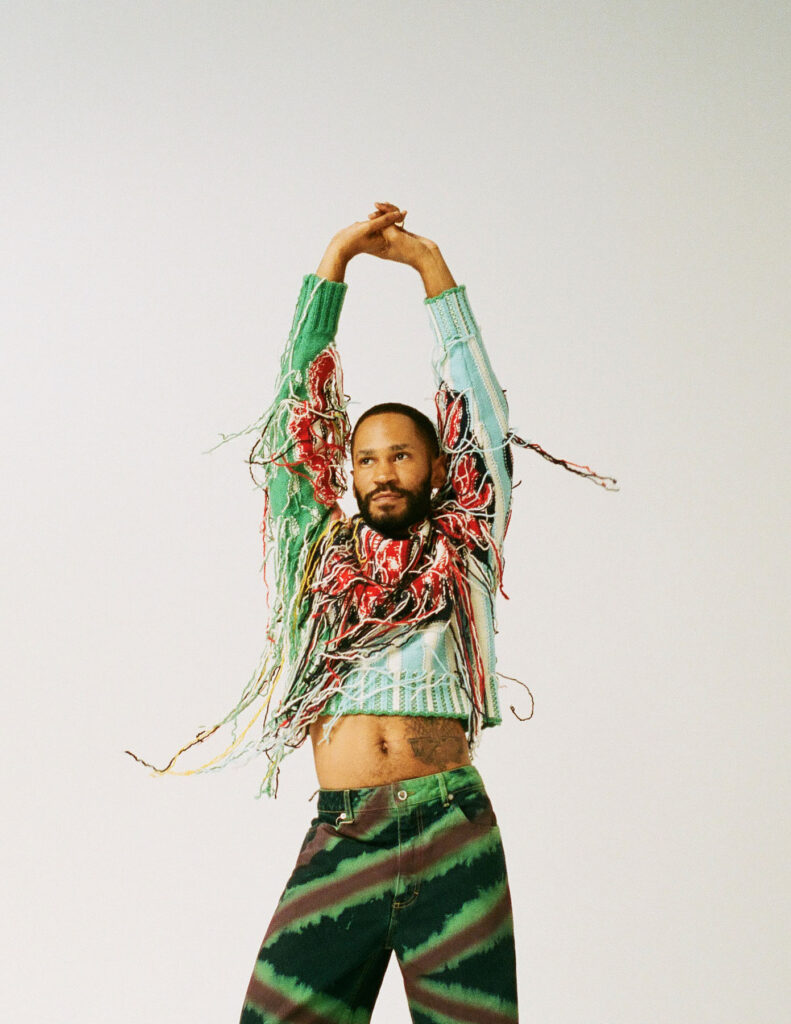

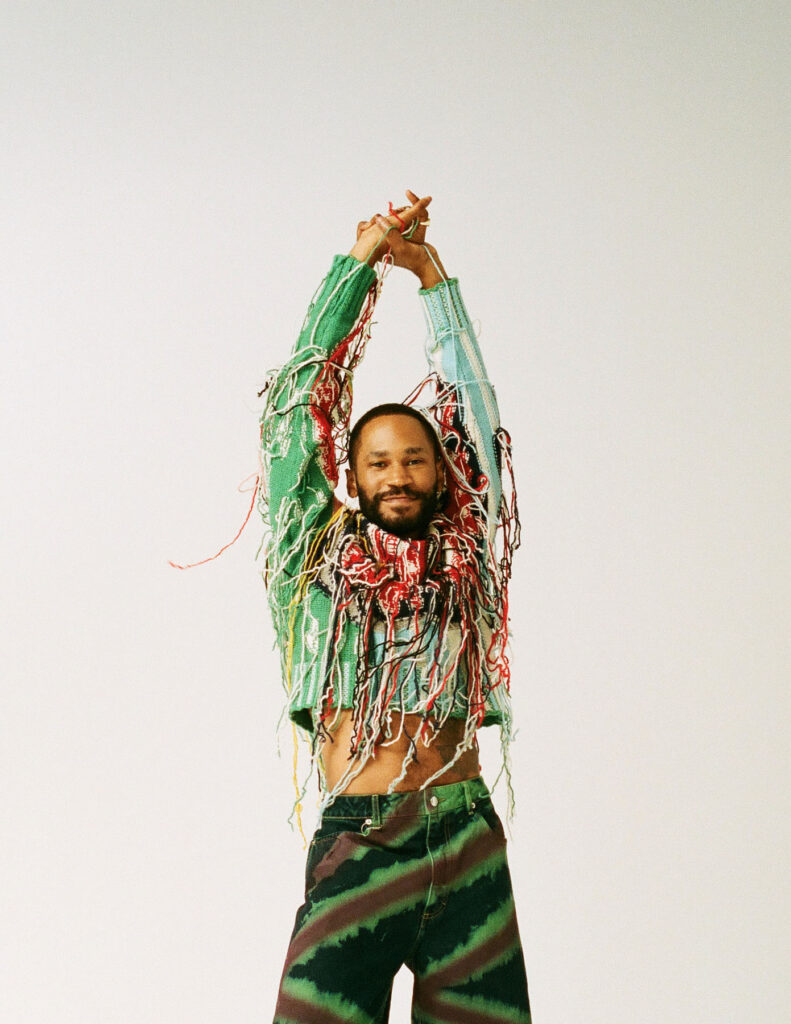

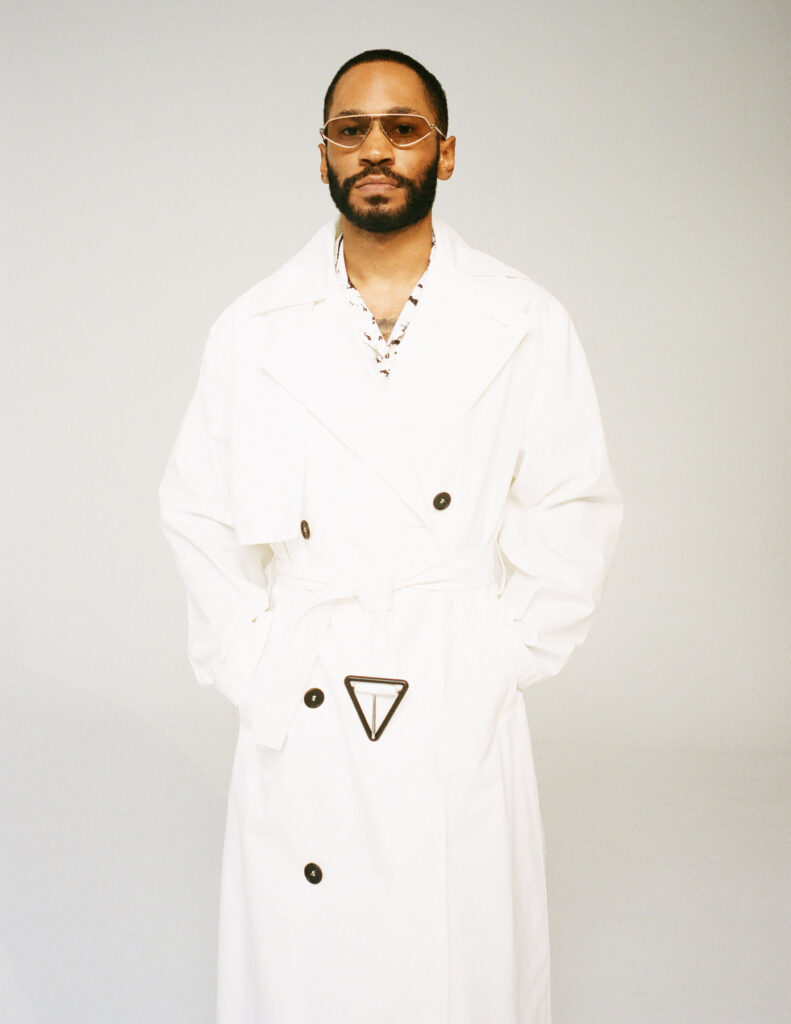

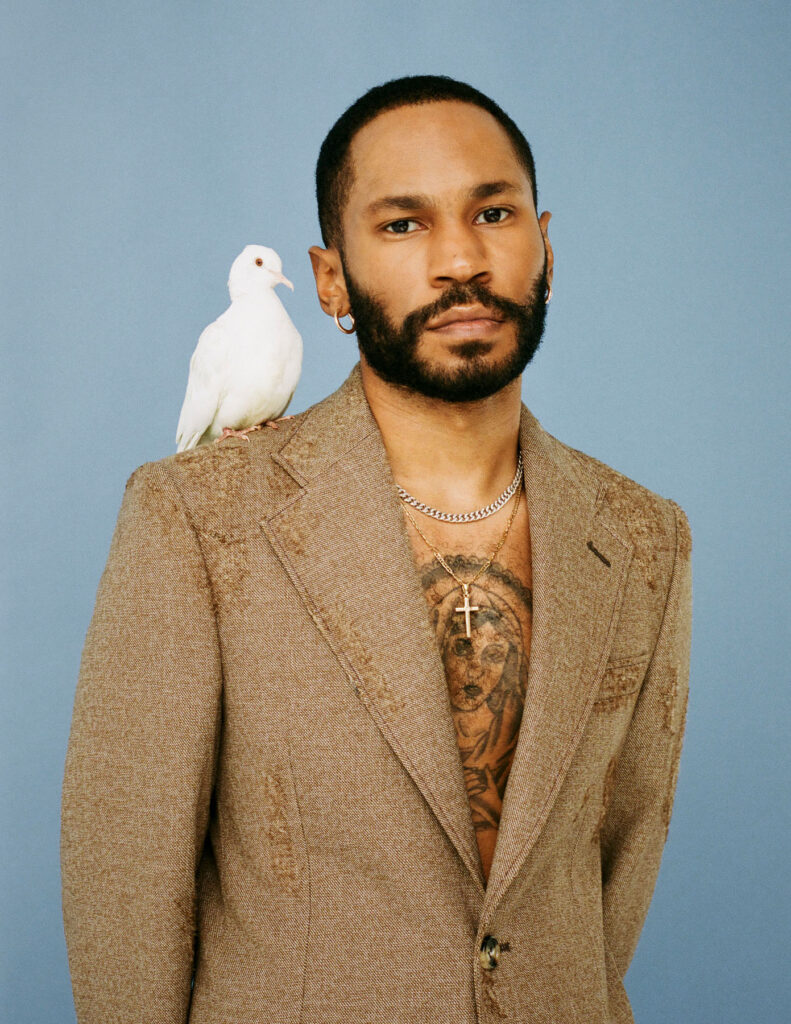

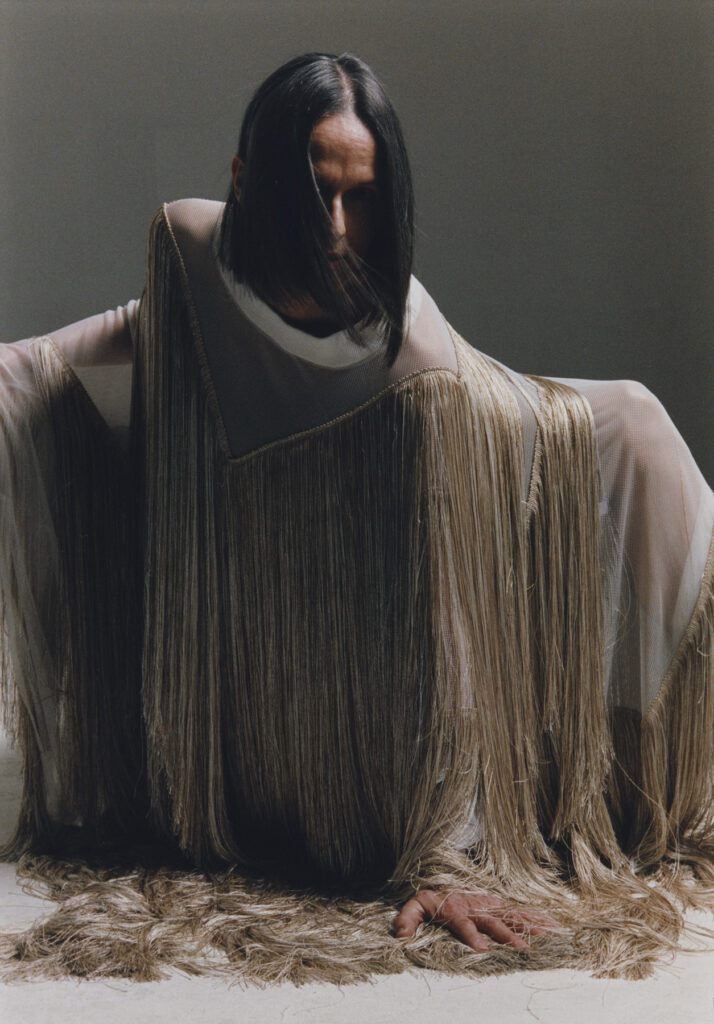

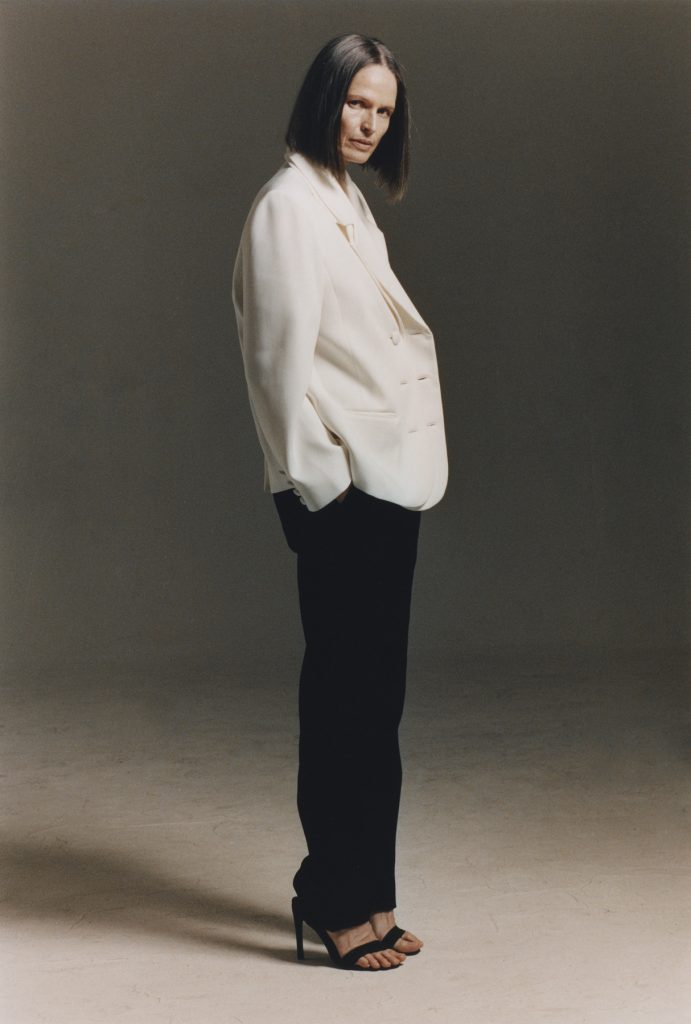

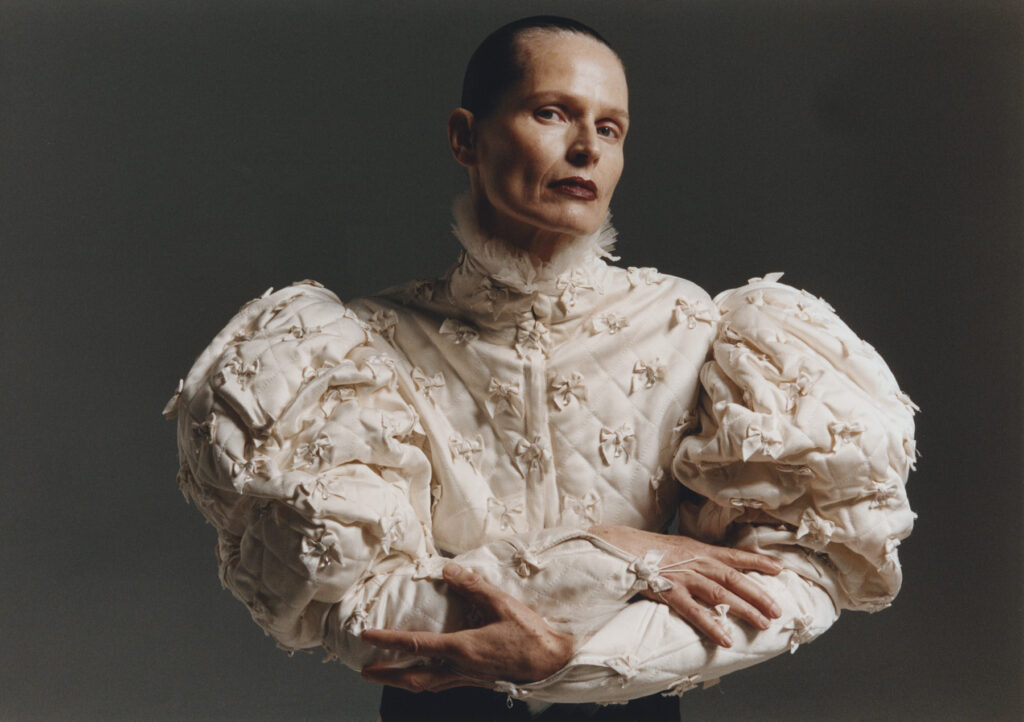

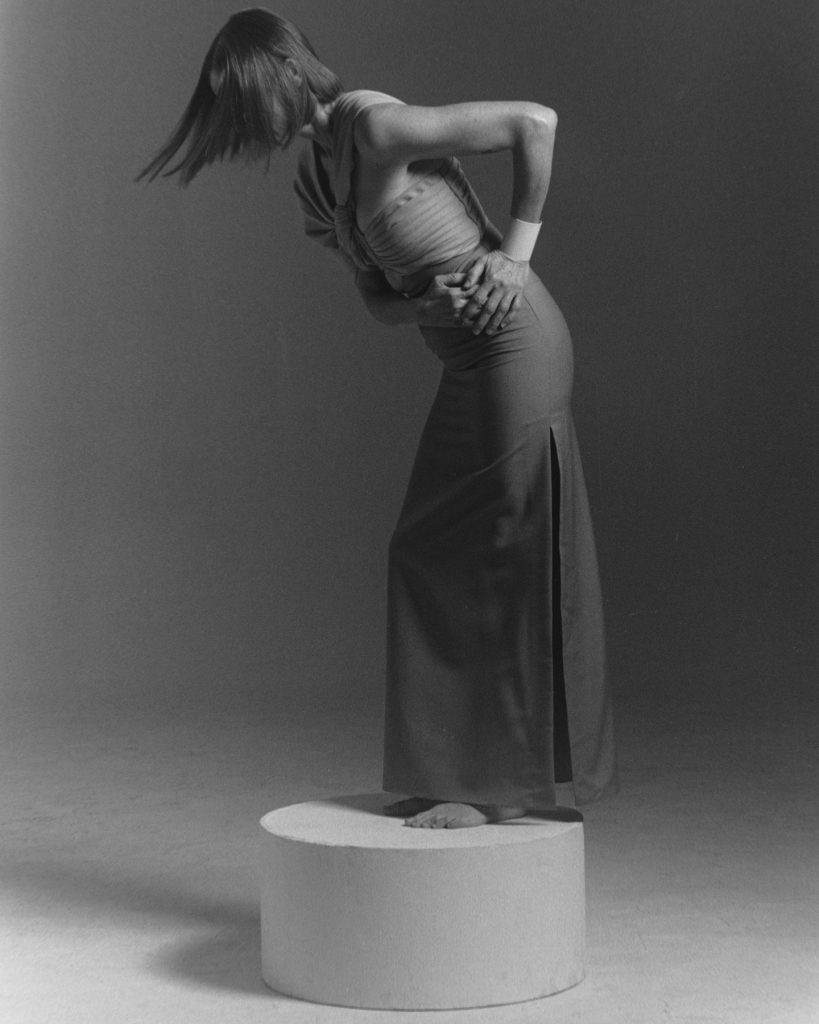

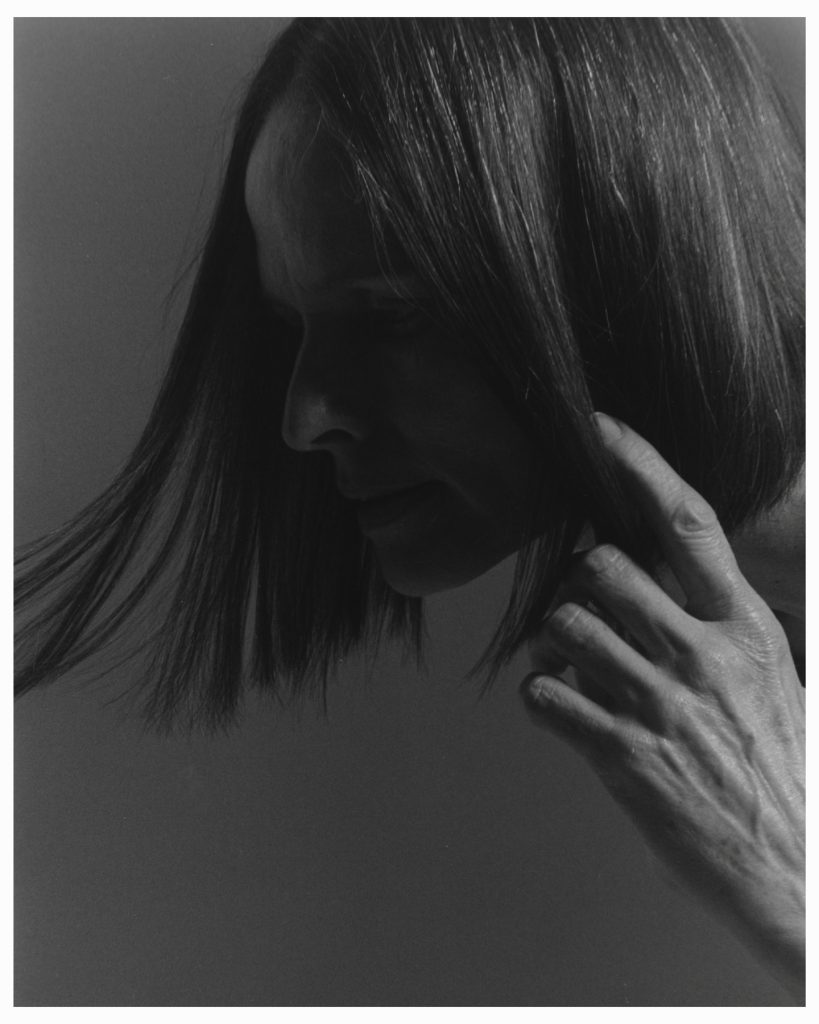

I speak to NR cover star, Sylke Golding, over the phone a few days after the shoot. How did it go, I ask? “It was great! A great little team. I always love it when they pick me,” she says. “At this point it’s such a plus.” Sylke started modelling at the age of 18, scouted – as she explains below – when living in Sweden. Now, age 55, Sylke is still modelling. After a break of a couple of decades in between, that is. Over the past couple of years, the fashion industry seems to have opened itself up to more diverse representations – widening the pool, as Sylke says. She had begun noticing this shift in the kinds of models she was seeing, not long before modelling came calling (again). It started around four years ago, when a colleague’s photographer friend was looking for models for an editorial with mature models. After came the runways (for amongst other brands, Deveaux), the street style spots (on Vogue) and the fashion editorials in print. Sylke’s certainly got the look – but as she ponders, what is that? “The way my bone structure is, because of the way the camera picks it up through the lens?”

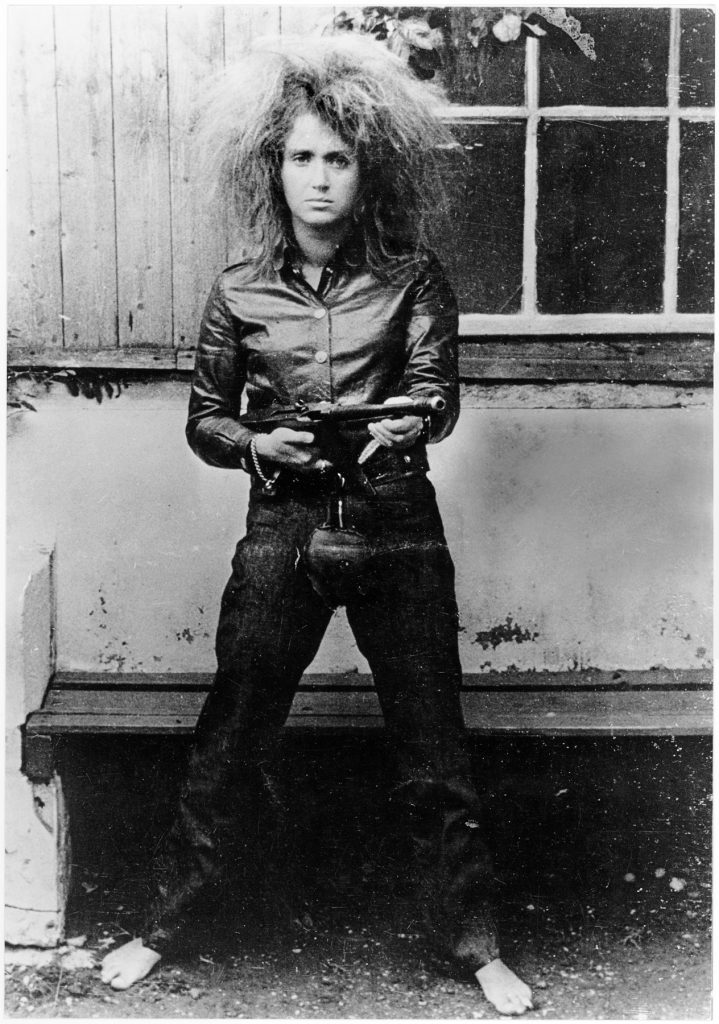

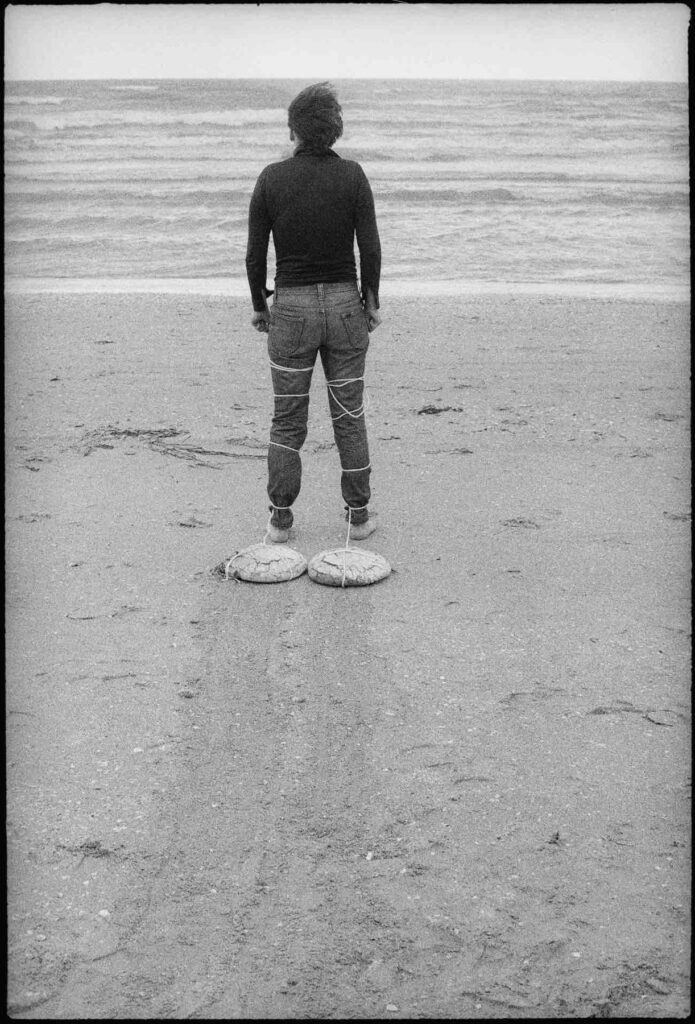

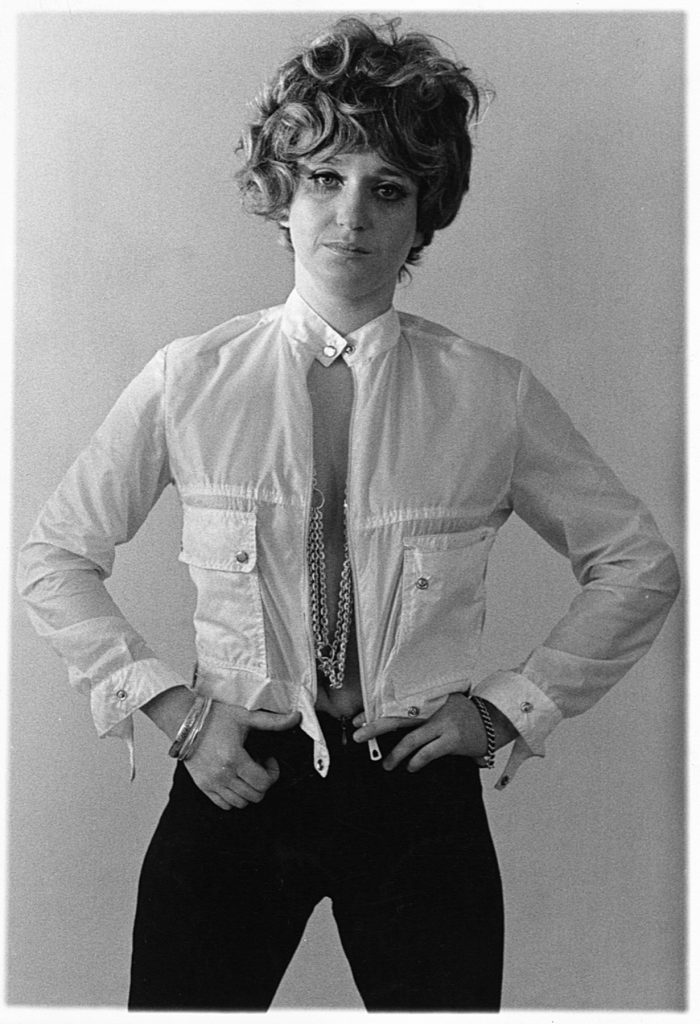

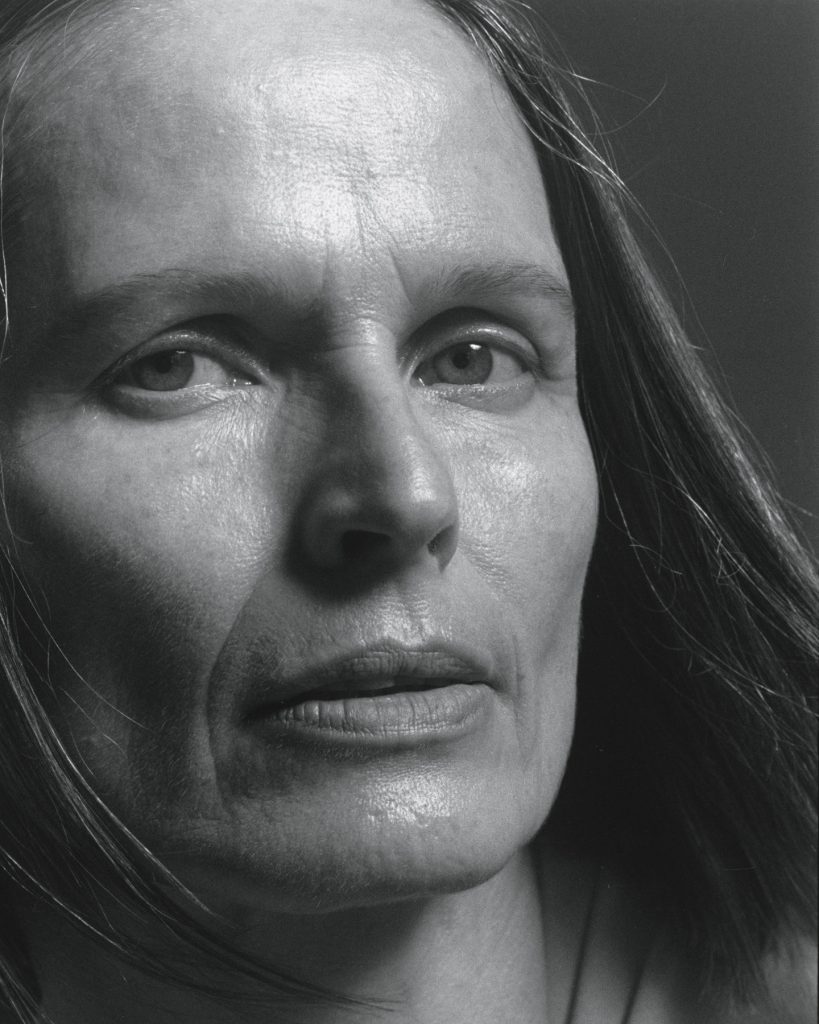

It’s curious listening to Sylke discuss the similarities and differences between her experiences of the fashion industry as a young woman, versus in her fifties. She describes the former experience of being about fitting a certain mould – and a quick stalk on Sylke’s Instagram brings up some throwback snaps from back in the day. There’s a shot by Patrick Demarchelier and an outtake from a Grazia cover by Steve Landis; it’s true, her bone structure really does work with the light. But what really shines through in her modelling work from today (and again, reflecting on what Sylke discusses below) is a certain joie de vivre – a smile that’s incredibly infectious, where great cheekbones can’t be replicated.

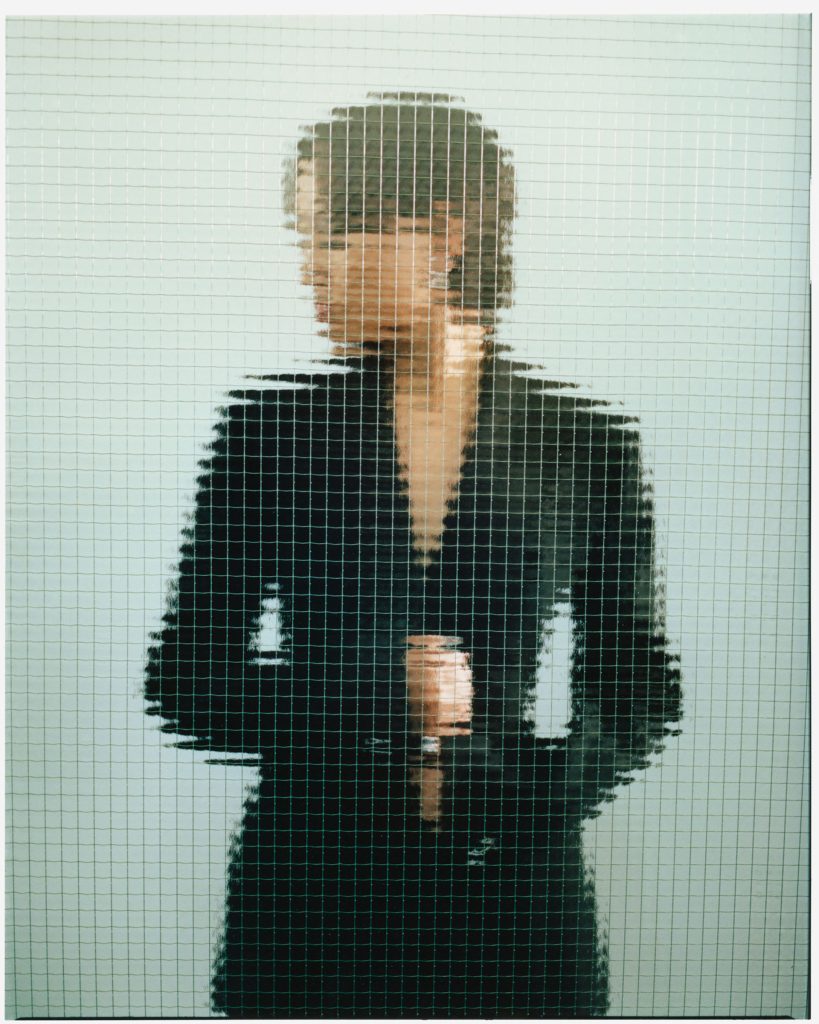

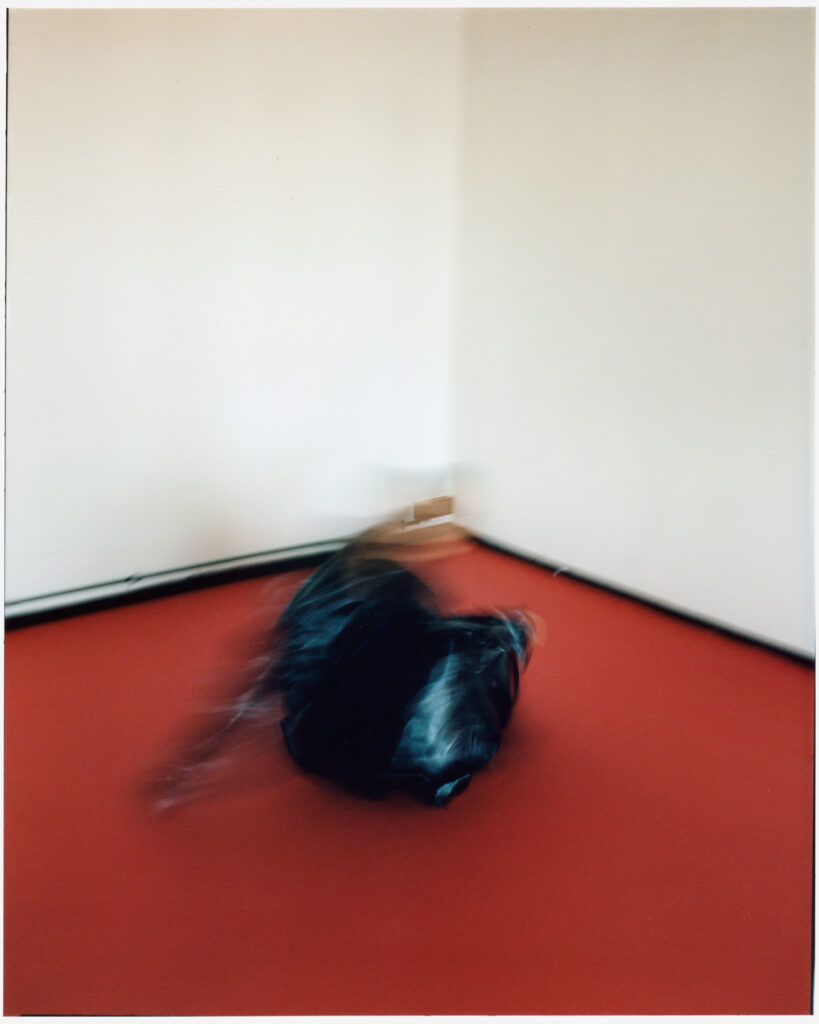

As important as someone like Sylke’s visible presence marks a shift in the fashion industry – the grey hair, the lines, the signs of ageing – it seems that she also really enjoys just doing the job. She speaks of how, though photographers more often shoot digitally these days, the recent resurgence of interest in film is interesting too. Sylke describes the “raspiness” that comes with film – “I love the dirt on it, so to speak, and the hue”. And there’s a different set-up that comes with film, too. “Now it’s all digital and usually you see it on a little laptop, and you get an idea but, [this shoot] was all on film. So, you take the first picture to check the light, take a few digital shots, but then you’re kind of in the dark. Sometimes, you just have to trust the process.” I ask Sylke if she finds it easy to trust the process, to trust the team. “It’s funny you ask that because, in my regular life, generally, I need to have control and I always try to think ahead and say, ‘What can I do?’” But with modelling, it’s about switching off – “it’s kind of freeing,” she says. Going with the flow, especially given the past two years of the pandemic, and being able to model breaks up the monotony of everyday.

NR: Is there anything you take with you to a shoot – something that never changes, regardless of the different jobs, teams or concepts you’re working with?

SG: Yes – it’s being me. All I can bring to the table is me. You know, sometimes I think, what are the expectations? But as much as I think, “Why me?” I’m also thinking, “Why not me?” I always try to remember that, with social media and my agency, [clients] pick me [for who I am]. I’m turning 56 in July, and although the modelling pool has gotten much larger because there’s more inclusivity, my age group is still much less represented. So, when [a client] picks me, then it’s like, they want me. I don’t know where I read this recently, but I read it and it sort of stuck with me, that people don’t change, they only become more of themselves. I think there is a lot of truth in that. I can be inspired by people, but then it still has to be translated into something because otherwise, we are all just copies, you know? It doesn’t work – and I think the camera knows that as well. You know, if you’re not comfortable within yourself, the camera will read it – and the people around you will read it. So I love that challenge of expressing you, and to answer your question, that doesn’t change.

“That is the challenge – to be actually me, to give them who I am.”

NR: Something you mentioned before we spoke on this call was the idea of destiny – and in relation to what you’ve just said, I wondered how that is realised for you?

SG: Destiny ties into when I first became a model. I lived in Sweden at the time, my family had left East Germany when I was 14. And then I was scouted when I was 18 and I started modelling in Italy and Paris. [Being scouted] came at a time when I really desired change and wanted to leave Sweden. But back then, there were only really one or two ‘moulds’ of model. I worked with a lot of beautiful young women, and we were all trying to fit that mould. If you didn’t fit that mould, there was work but it was much harder to reach a point where you could work consistently. And then when you reached 25 or 26, it was done. It really slowed down to the point that you couldn’t help but see the messages: “Look, there’s a door and it says exit. See it?” So then I just stopped at that point and turned away from modelling. I had dropped out of university to pursue modelling, and [then] I had to find out what I wanted to do next. I did a bunch of jobs, a couple of decades went by – you know, the quote un-quote ‘regular life’. And I never really thought about modelling again. But in the past five years, I started seeing little signs that something was afoot. Friends would say, “Maybe you should model!” But I was like, no. No, I should not. And

“lo and behold, modelling came and found me again; I was asked by a photographer who was looking for a mature model.”

And then I was like, “Alright, what the hell? Why not?” I did it, it hit social media, and then it just happened. So I often find myself thinking about destiny; I feel like both times modelling came, I didn’t actively pursue it. It pursued me. I would say that the only way I would do it again is if it came and knocked on my door. And I said it many times. So, lately, I’m really of the mind that you should be careful what you say because once you say things out into the universe, it has a way of responding. And it’s for the good, it’s for the bad – whatever the energies you put out there, you will attract them. So, I wonder how actively, or subconsciously, did I will this to happen?

NR: Do you feel like your visibility is as important for you as it is for other women to see?

SG: I hope so because you see women, or society on a whole, struggling to accept age – women growing older, men growing older. I see men colouring their grey out and I think it looks ridiculous because you can see it. I try not to judge, but it’s just, you can see it. I rationalise the process for myself, and it makes me stronger, which is that in the end, people are scared of dying. And we all, in some way, have to get to grips with that. And I think the problem is that, of course we want to postpone it, but that’s all we’re really doing. I want to encourage everyone to find a way to accept it because I’m trying just the same to accept this. So, I hope that [my visibility] helps. I hope changes in the industry are here to stay; that they are truly opening up, and that the pool remains larger, and become larger. And that everybody is included because, as they say, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Who’s to say who is beautiful or not? I want [to push for] acceptance of what is real; I strive for that. I want to be honest; I want it to be real – to reframe that into a positive. And I hope it encourages people.

“I hope [my experience] tells the story that, you know, you could be happy with growing older. You can be fulfilled and satisfied.”

NR: The industry is notoriously gravitated towards youth. From your experience of being a model at a young age, before coming back to the industry later on, has much changed?

SG: It has, and it hasn’t. The first shoot I had, it was like nothing has changed – the hair, the make-up. The process of getting ready hasn’t changed. It’s still the same creative process. The pool has gotten a lot bigger. I work with models that could be my children; if I had children, they could be my children. Back then,

“I think it was more about fitting a mould, and it was less about who you were as a person.”

And now, it’s much more like, “Oh I like them. I think they could really contribute to the story.” I think that’s a huge change – they want character, you know. They don’t just want a prescribed performance from the model. I think it’s much more collaborative, even from the model; it’s like, “Show us who you are.” Overall, it’s the same industry. It’s the fashion industry – it’s the same. Same exciting, crazy journey and I think it’s full of people who just love excitement because every day, you pretty much meet new people and it’s a new scene.

NR: On your Instagram, there’s a post where you say that it’s a myth that age is just a number. And going back to what you said about how, as you age, you become closer to who you truly are – is that what you meant about this ‘myth’?

SG: You don’t have to be confined by the number of your age, I know what people mean by that, I think it’s well-meaning. And I used it too in the beginning, but then I thought about it. It isn’t just a number. Age is about acceptance, it’s not just a number because I’ve got here. I’m lucky to be here, every day is a plus – to wake up and be healthy, and to find myself in this unique position. And I’ve said this before and I think it holds true: every spot, every wrinkle tells a story.

Credits

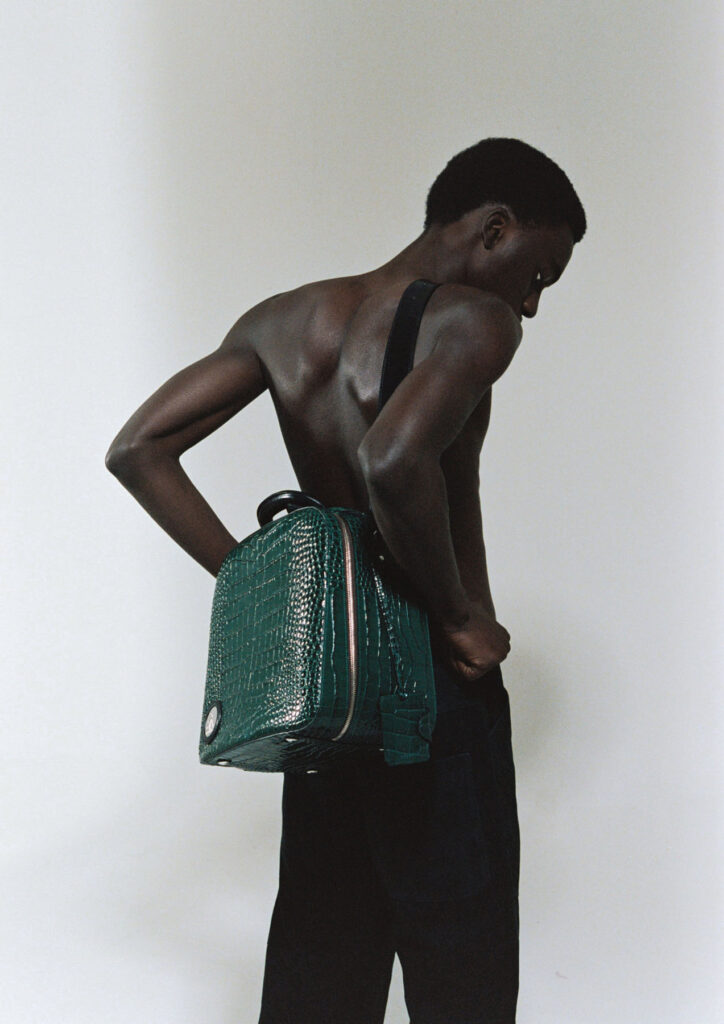

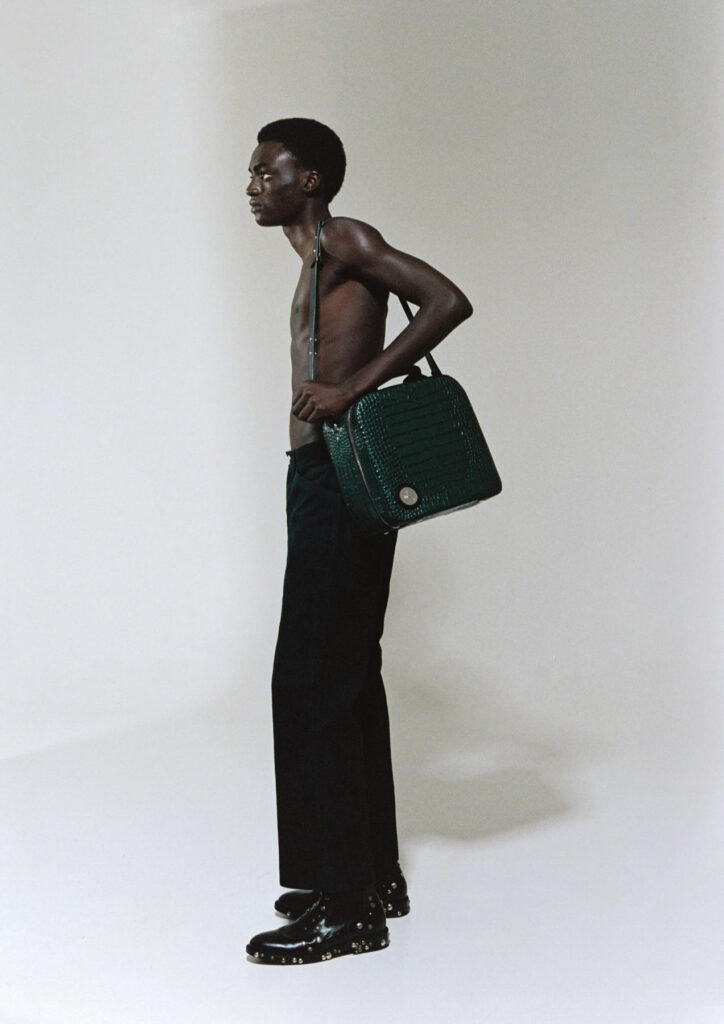

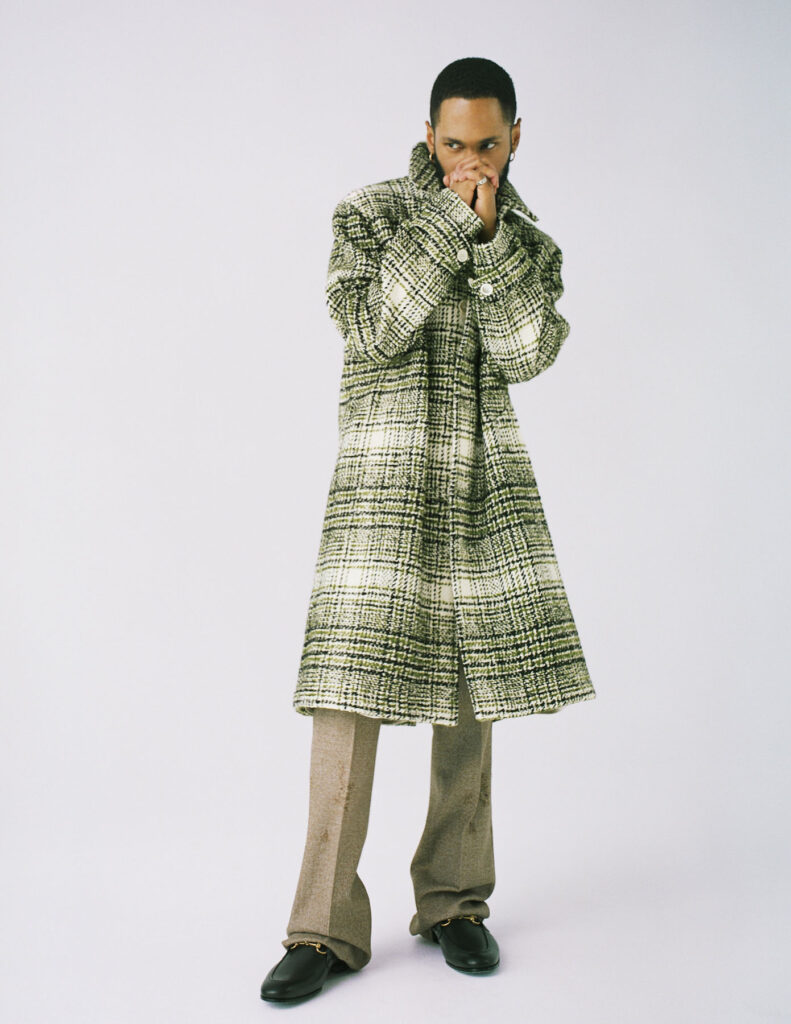

Model · SYLKE GOLDING at MUSE NYC (Agent DANIEL SISSMEIR)

Photography · RICKY ALVAREZ

Creative Direction · JADE REMOVILLE

Fashion · SUTHEE RITTHAWORN

Makeup · MARIKO HIRANO

Hair · JEROME CULTRERA at L’ATELIER NYC

Writer · ELLIE BROWN

Fashion Assistant · JOAO PEDRO ASSISS

Special Thanks · MALENA HOLCOMB and DANIEL SISSMEIR