In Search of Opposites

Shirin Neshat (Farsi: شیرین نشاط, b. 1957) is an Iranian-born visual artist who lives in New York City, known primarily for her work in film, video, photography, and opera; directing Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida at the Salzburg. Her artwork focuses on the notion of opposites between the East vs. West, femininity vs. masculinity, spirituality vs. violence and the beautiful vs. the disturbing; highlighting the contradictions between these subjects, through the lens of her personal experiences of exile and finding a sense of belonging.

She has exhibited her work internationally at numerous museums and galleries, including: the Serpentine Gallery, Stedelijk Museum, Hamburger Bahnhof, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Faurschou Foundation, the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and Museo Correr, which was an official corollary event to the 57th Biennale di Venezia in 2017. Neshat’s Turbulent was awarded the Golden Lion Award, the First International Prize at the 48th Biennale di Venezia (1999). Her first feature-length film, Women Without Men (2009), received the Silver Lion Award for Best Director at the 66th Venice International Film Festival. Her other feature films are Looking For Oum Kulthum (2017) and most recently Land of Dreams (2021), which premiered at the Venice Film Festival.

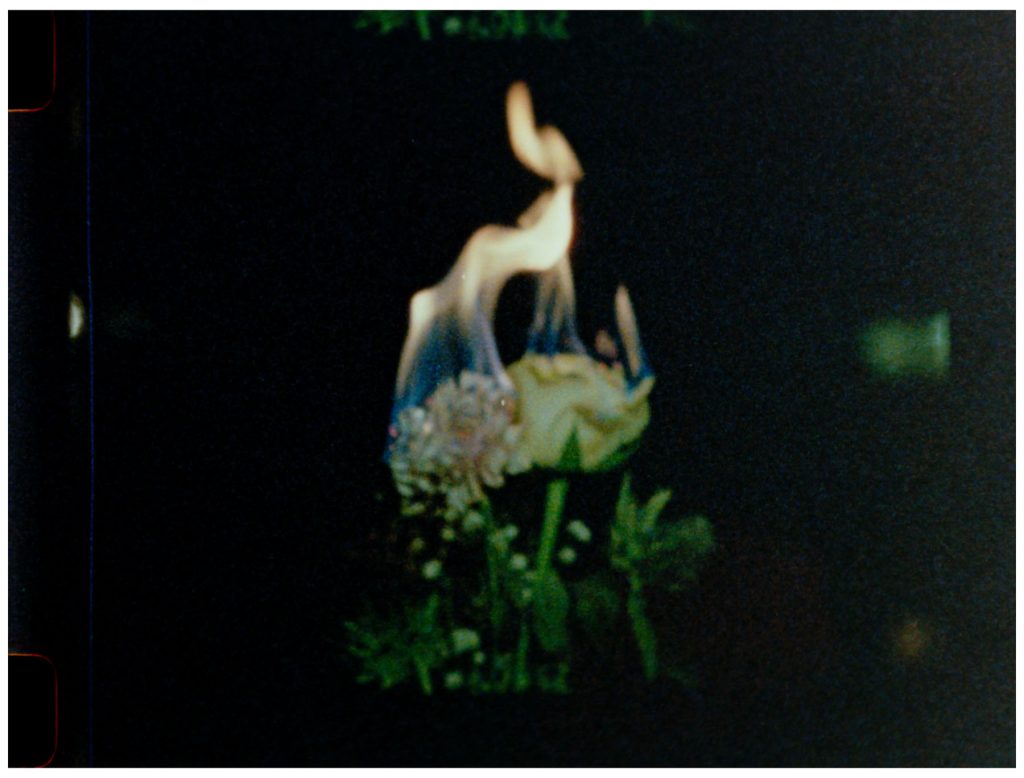

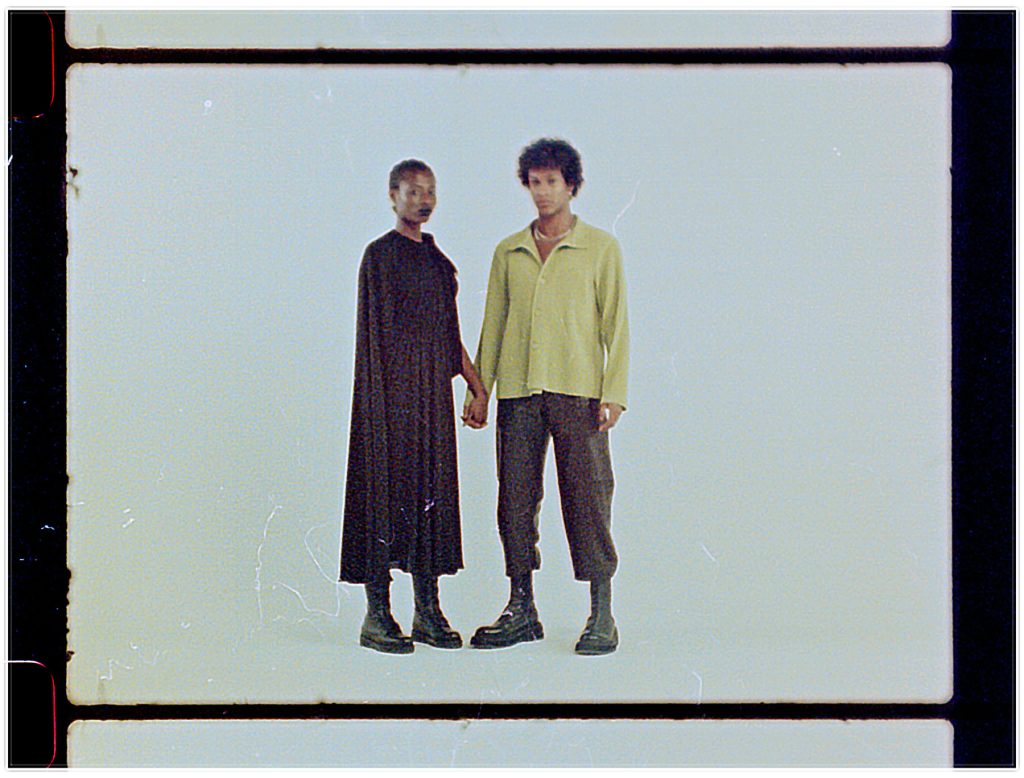

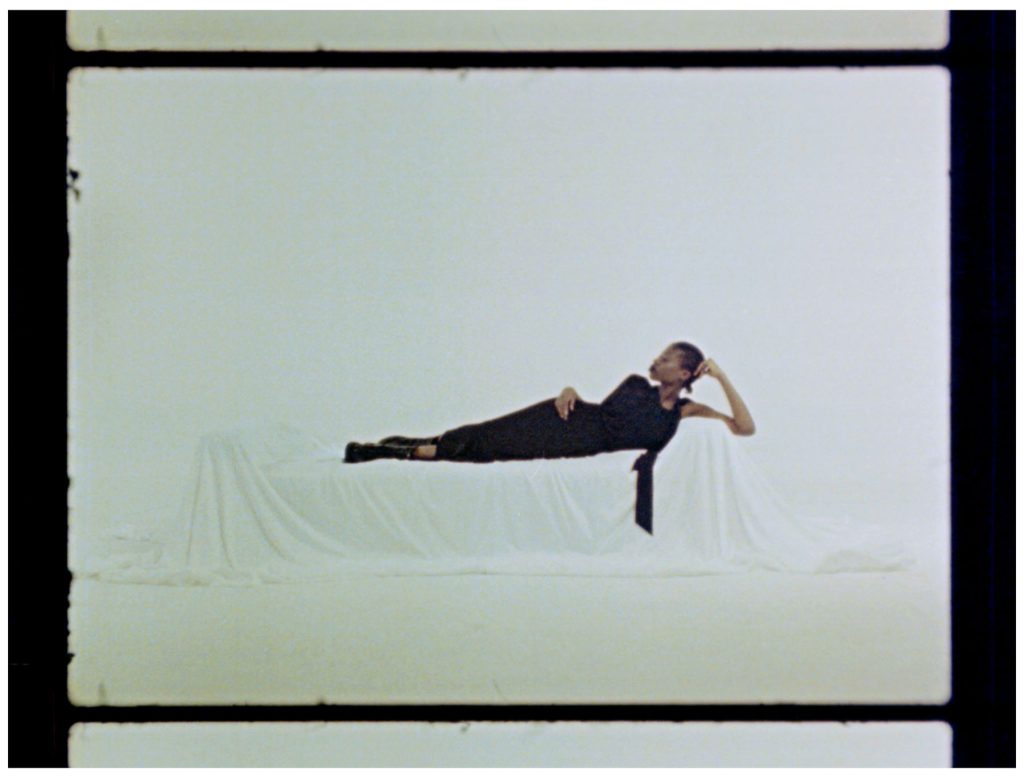

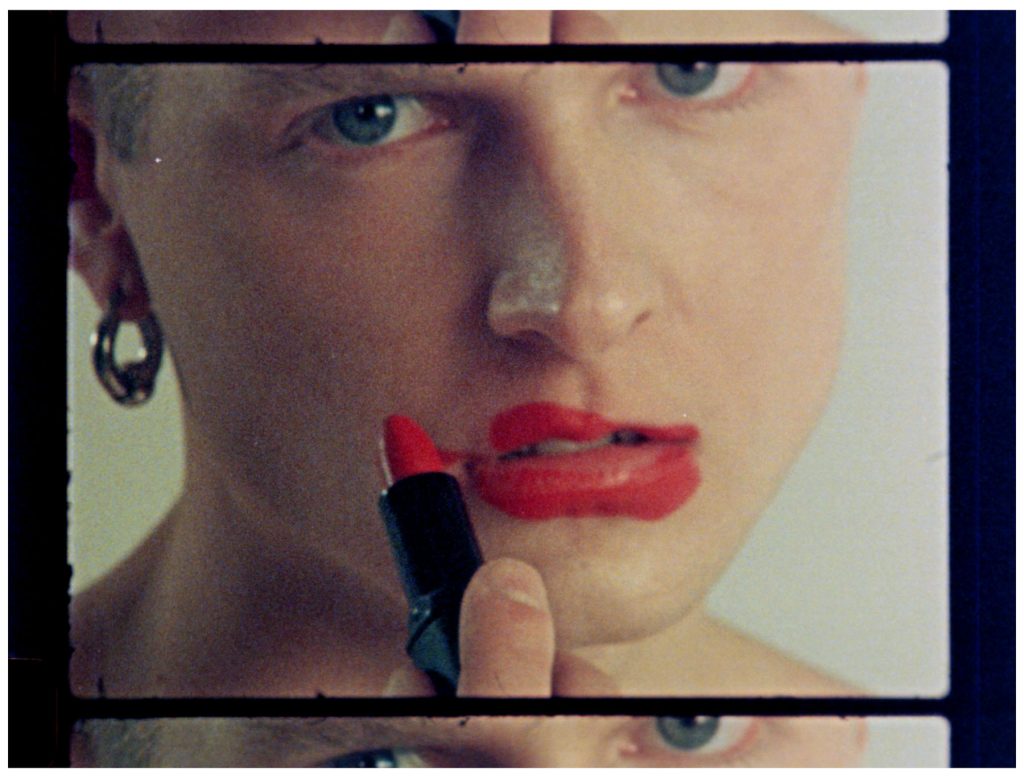

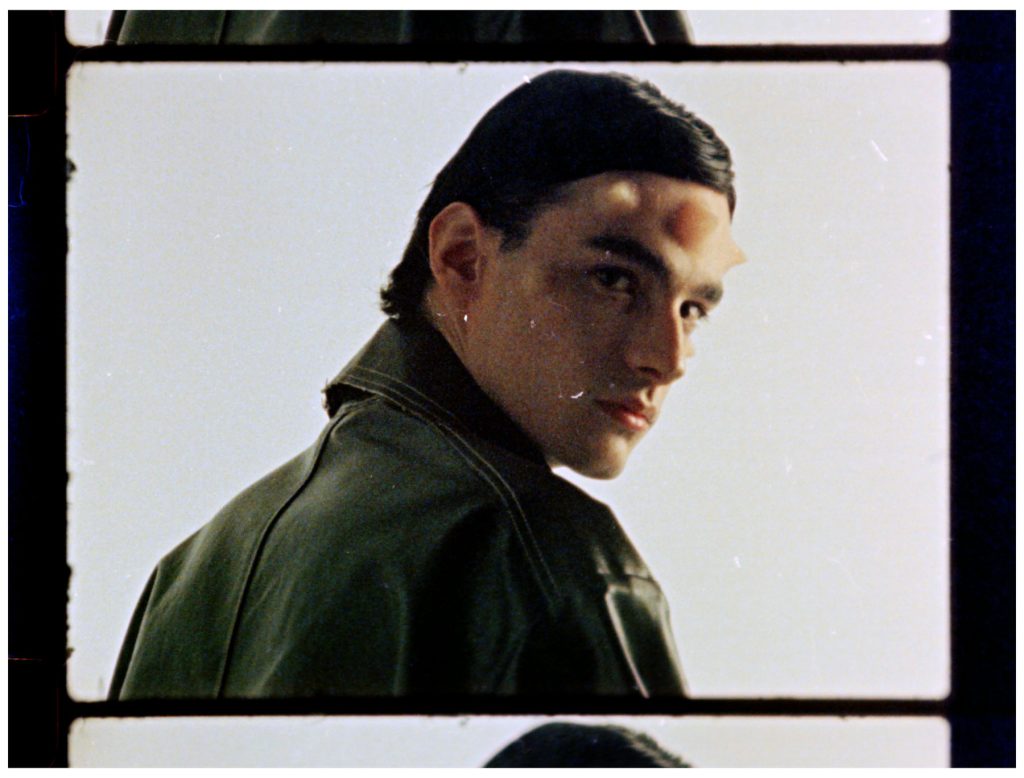

In concurrence with her recently released short film and exhibition The Fury, NR Magazine spoke with Neshat about her memories of her childhood, transition from working between different mediums, working with subjects originating from the Middle East to the US, and about the excitement of embarking on her most recent projects.

Dara: I would like to start by asking you about your early memories of your childhood growing up in Iran and later moving abroad.

Shirin Neshat: I grew up in one of the more religious cities in Iran, Qazvin, with a lovely family. My father was a farmer and a physician, and my mother was a housekeeper. We were 5 children, and we had this dream life in a home with a beautiful garden. Therefore, my early life in Iran, up until I was 17, was quite normal and peaceful. I left Iran at the age of 17 because my father, like many other Iranian families at the time, wanted me to continue my education in the West. So, I came to Los Angeles with my sister, and that was a pretty dramatic transition for me. This was because the image I had in mind of America and what had been depicted for me was very different from what I saw and experienced, which caused me to fall into a depression. This period was in 1975, a few years before the Iranian revolution, and I remembered I really wanted to go back to our small town because of how ill I was feeling leaving the proximity of my family.

Unfortunately, my father was quite persistent for me to stay, and shortly after the revolution happened in Iran. During this period, I had just turned 20 and began my studies at UC Berkeley. Therefore, the early days of my studies in college coincided with the revolution taking place, followed by the war with Iraq that led to the breakdown of diplomatic relationships with the US, and my total isolation from the rest of my family due to not even having remote family in the US. This experience was quite horrifying as a 20-year-old who never really felt comfortable living here, and this feeling was perpetuated by the inability to communicate with Iran through post or telephone service.

Therefore, my early memories of my childhood in Iran were quite peaceful and happy, but this quickly transitioned into a very dark period of my life was quite traumatic, as I’m sure many other Iranian people that experienced this separation could relate to. During this time, I suffered from anxiety and was stuck in this constant feeling of being ill that caused me to not perform well in my studies. I think this period, from when my sister left back to Iran a few years prior to the revolution until when I eventually moved to New York in 1982, was the most difficult period of my life.

After moving to New York, I started to finally find the right community, and I married my Korean partner at the time, which led me to join him in running a non-profit organization dedicated to art and architecture. Starting this new life in New York was hard at first because I didn’t know anyone and had no money, but due to the nature of the city, it allowed me to find a sense of security and community. During this period, I didn’t have the opportunity to go back to Iran and see my family for 11 years, partially because of the war between Iran and Iraq and the diplomatic breakdown between USA and Iran, but I finally had the opportunity to go back in the early 1990s.

The reason I explain this background is that it has a lot to do with the art I create, and the emotional, psychological and even at times political substance of my work. My work is a reflection of the sense of exile and loneliness I experienced during this period, and the anxiety and alienation that came from that. Therefore, many of my characters in my films are very representative of these feelings. Following my return from Iran in 1996, due to me beginning my work as an artist, I have been unable to revisit ever since.

Dara: I can’t imagine how difficult this transitional period was for you, especially considering all the events that took place during that time in Iran. I’m sure many Iranians moving abroad prior or during this time can relate in their own way to the feelings you’ve shared. I’m curious to hear more about your experience of visiting your family for the first time after over a decade, and how this experience felt and influenced your work that followed.

Shirin Neshat: It was both exhilarating and horrifying. I remember during this time my son was born; he was 3-4 years old and had a Korean-Iranian background. It was kind of strange after 11 years because there was a distance between the life that I had lived and the life that my family had lived in Iran. There had been so much that had happened: the revolution, war with Iraq, and the economic situation that had followed, which caused a gap between us that was hard to distinguish for me – understanding who they were before and who they were now.

On a public and societal level, everything had transformed, even visually. It was almost as if the color had been lifted off the cities, and everything had become black and white. In some ways, I felt excited because I felt the life that I had lived during this time away was so meaningless. I thought my life during this time was so individualistic and so much of it was about me caring for only myself. Being in an environment where people had suffered so much, in the early 1990s where all these events had taken place so recently, and having the opportunity of seeing and reconnecting with many of my old friends, I finally could try to understand and feel what had just happened. I had the opportunity to read books and material on all the events that had taken place, and also hear experiences to try to immerse myself in this time that had already passed.

Therefore, when I returned to New York, I found it really difficult because my heart was no longer in working on our non-profit organization with my husband. I just really wanted to go back again and I did a few times until I had trouble being able to visit. All of these interactions, impressions, and inspirations I had during my visits to Iran ultimately culminated into my art. What many don’t understand is that prior to these initial visits to Iran, I wasn’t an artist, and I was mostly interacting with art through helping other artists in their practices. But I realized that all I wanted was to connect with Iran and what I had just witnessed during my time there, and art very organically became this connector and a great tool for raising questions or creating a dialogue with all the issues I found interesting.

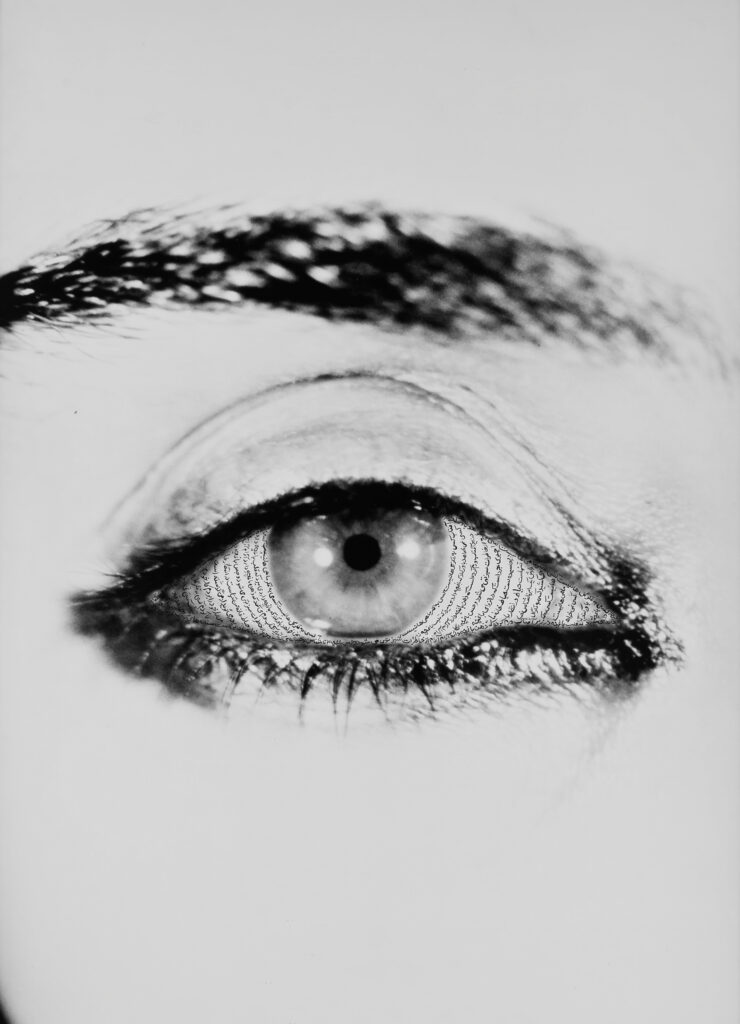

I believe that there was a misunderstanding of people thinking I was trying to make a statement or claim towards the events that had taken place, but this was never my intention. I knew very well that I was an outsider, and my intention with my work was to focus on a subject that interested me, and I would try to research that idea. For example, with Woman of Allah (1993), I read my friend’s philosophy thesis on the subject of Martyrdom (Shahâdat) in post-revolutionary Iran, and I was mesmerized by his analysis of the correlation between love of god in religion and the violence in death. To me, this was an incredible paradox that inspired me to make that series of photographs,. To this day, I’m attacked because people think that by creating this body of work I supported the fanaticism of the current regime, and on the other hand, the government thinks that I was critiquing the regime. My intention with this body of work was to raise questions on a very symbolic and conceptual level.

My artwork was triggered by my return to Iran through my experiences and inspirations during these visits, and it grew from there very organically from one medium or topic to another.

Dara: What really moved me about this body of work, Woman of Allah, is the juxtaposition present in the heaviness felt in the composition of the images and the use of calligraphy, and on the other hand, the sense of vulnerability felt through the presence of the woman’s body. As a viewer, I found myself positioned at the center of this paradox. Can you further discuss your position and process behind this series and your decision to use calligraphy in your work?

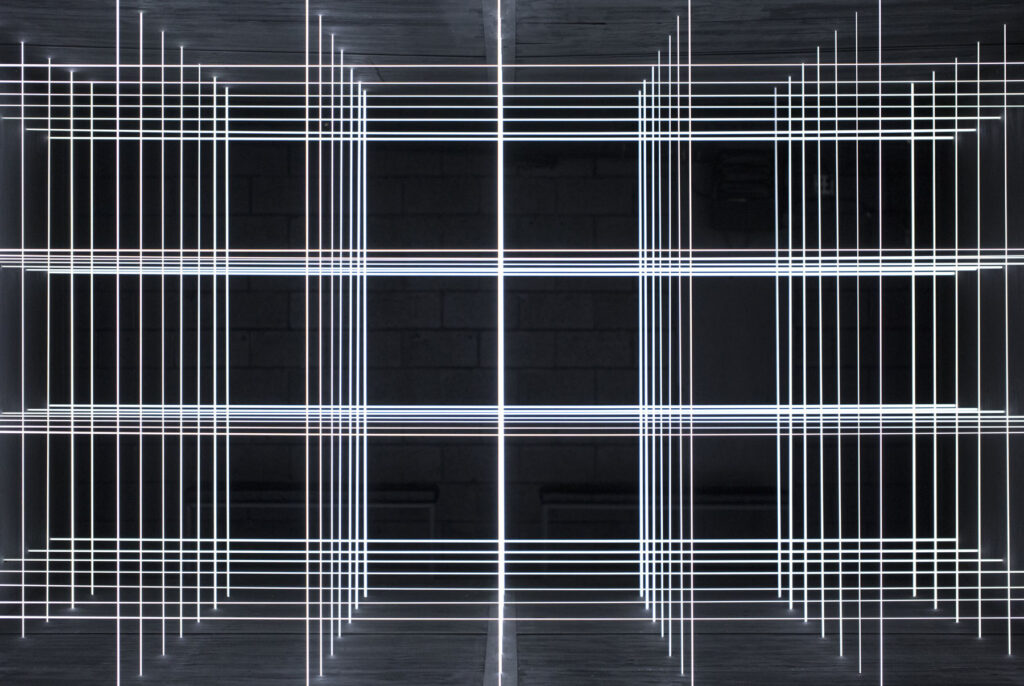

Shirin Neshat: You have to keep in mind that I was educated in the West and due to this, I developed a Eurocentric background in my relationship with conceptual art. On the other hand, my subjects are very rooted in Islamic and Persian art and architecture. If you look carefully into my work on an aesthetic and visual level, you notice an emphasis on symmetry, repetition, harmony, and integration of text. There is a reference to sacred text experienced in Persian poetry and Islamic architecture. Therefore, many of my ideas are borrowed from authentically traditional Persian and Islamic art that points to my heritage, but the language of my work is very much that of conceptual art. I grew up influenced by the work of artists like Cindy Sherman and artists who were predominantly working in self-portraits. Therefore, the enigma and abstraction that are present in my work are not coming from traditional influences but my experience of Western conceptual art.

The paradoxical sense of duality you mentioned about Woman of Allah and my work at large comes from my subconscious strategy of finding contradictions, opposites, and paradoxes in the work I create. This duality is evident in Turbulent (1998), Rapture (1999), The Fury (2022) and my other work as well. These conflicting ideas and notions of opposites, for example, men vs. women, spirituality vs. violence, the beautiful vs. the disturbing, or open natural landscapes vs. controlled fortresses, both aesthetically and conceptually influence my work, ranging from photography, film and opera. This duality is represented in my emphasis on working in black and white, juxtaposing realism with surrealism and dreams, and has stayed constant throughout my work.

Dara: Before we move on to your films and your transition into moving images, I want to take this opportunity to further discuss your body of photographic work, such as The Book Of Kings influenced by social and political movements throughout the Middle East.

Shirin Neshat: Over time, I realized that subconsciously I found myself referencing history in my work. For example, The Book Of Kings (2012) was influenced by the Green Movement, Women Without Men (2009) was influenced by the 1953 Coup, and Looking for Oum Kulthum (2017) was influenced by Egyptian history during my time there in the Arab spring. I tend to approach history in a very fictionalized way, and in The Book Of Kings there is a focus on this notion of patriotism influenced by Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (Book Of Kings), which is a long epic poem of tragedies that focuses on the core narrative of these heroes that self-sacrificed for their virtues and their nation. Ferdowsi’s book is largely credited for saving the Farsi language following the Arab conquest that ignited the introduction of Islam in the Middle East. Also, The Book Of Kings is influenced by the more recent Green Movement in Iran, which was a forward-thinking movement not focused on religion, and people demanding a new idea of liberty while not overthrowing the government. These powerful notions of the spirit of patriotism that later on continued throughout the Arab spring tend to always intersect with genocide, violence, and cruelty, similar to what is present in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh where you read about men’s heads being severed. I found this tension between compassion and love for the nation, and the brutality, violence and genocide that came with it incredibly moving and profound. I represented it in this series of photographs through symbolic gestures such as having a group of patriots with their hands over their hearts, a group of villains with scenes of war from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh inscribed on their bodies, and a group of 45 images depicting innocent bystanders observing this circus. My intention with the series of photographs was to capture the spirit of patriotism during the Green Movement in 2009 and for it to serve as a remembrance for those who lost their lives, and also as a reminder that history tends to repeat itself.

Dara: It’s interesting to hear you move from such a personal subject so close to you to a more expansive conversation with a wider audience throughout the Middle East. I’m curious to hear why you decided to transition from photography to moving image as a medium to continue this discourse. Also, as a starting point, I wanted to ask you about your first short film Turbulent and your application of music as a communicative tool throughout this project.

Shirin Neshat: I think after Woman of Allah I received such a dogmatic response to it as a project, a response that was quite political and the judgment was so heavy. This experience made me feel that the nature of photography limited me from building more ambiguity, and to be able to take the audience to a place where they were not forced to impose their relationship to the subject of politics. Therefore, transitioning into moving images felt like a massive departure for me. It opened a new door to a whole new medium that refused to be reduced to these types of judgments because I had the opportunity to be far more evocative and abstract – even if my work was politically charged. The other advantages this new medium offered were the opportunity to set a background or a landscape, and to introduce music and choreographed performances. Also, it gave me the ability to situate my audience to have them experience it in a way that I could control as an artist.

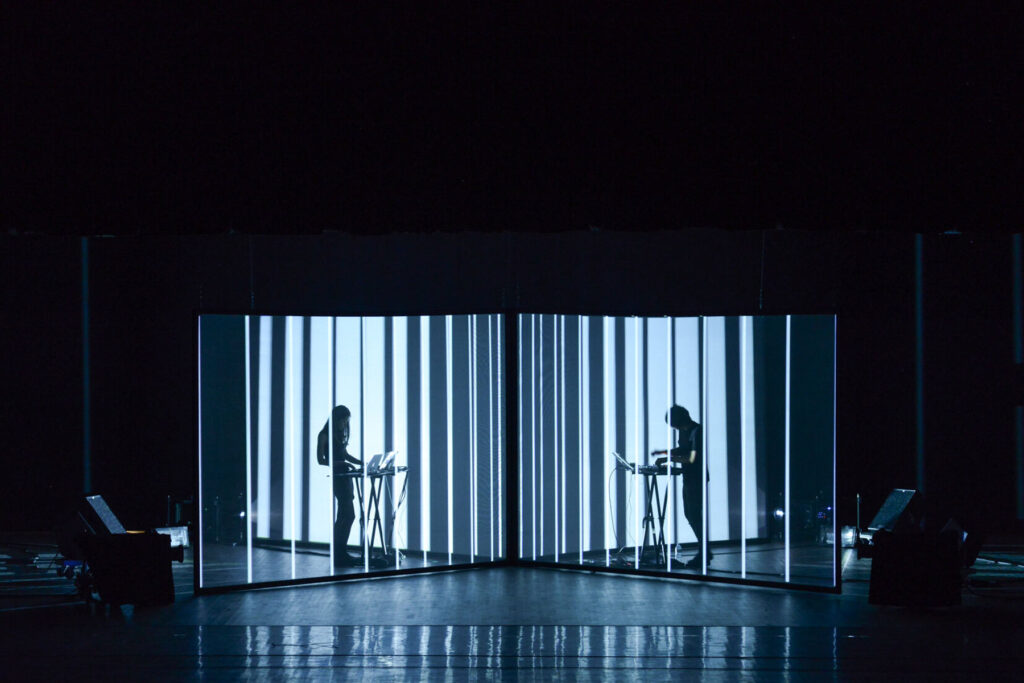

With a photograph, as a viewer, you are placed in a situation where a single photograph has to say everything. This became quite difficult and problematic for me because most of the time, that image is reduced to a few symbols such as a veil and a gun, and this leads to the loss of every other complexity present in the work. Therefore, I found my transition into film as a beautiful new and freeing journey. Turbulent focuses on critiquing the sociological issue of women in Iran being deprived of the experience of music. It does so by again placing the audience in a conflicted point between two opposites: one being a man performing a song to an audience and being applauded for his performance, and on the other hand, a woman performing alone with no audience, and her performance escalating into a form of protest. But this is the impression that is first felt on the surface of the film. Gradually, there are these layers of meaning that begin to show themselves below that surface. There is a conflict between the conformist and the rebellious, but also between tradition and the act of breaking away from that tradition; to start something new. What I loved about Turbulent was that I felt that my audience, from every corner of the world, got it and truly understood it, and I didn’t have to say anything in that process.

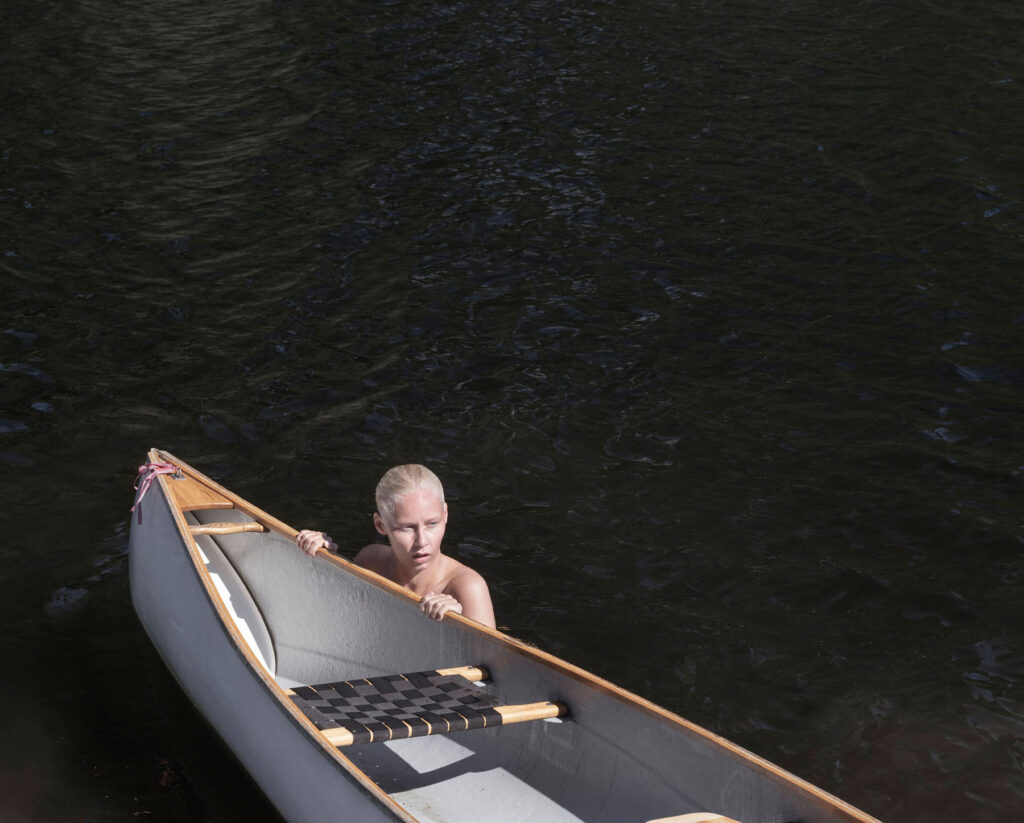

This was a great realization for me that moving image and all the qualities that it comes with granted me the opportunity to create experiences that are far different from what can be achieved with a photograph. This made me step away from photography for a few years and make other films, such as Rapture, which again introduced a paradox through two separate screens; one showing a group of men in a fortress and the other showing a group of women in nature. But at the end, the audience understands the message behind this enigmatic film, which was that the women started this journey from where they started and end up in this boat that they depart in and leave, whether to commit suicide or reach freedom, but the men end up staying and being left behind in the same place. So there was this symbolically calculated outcome that was delivered through form, shape, music and poetry leading to an end that evidently had its sharp knife.

This quality of progression in storytelling in moving image inspired me to continue making many more films and staying away from photography. When I finally decided to return to photography, I had a completely different approach to it as a medium.

Dara: I found your use of two screens in these films quite effective because, as a viewer, you find yourself in the middle of two subjects that are having a dialogue with each other. This experience can be quite emotional and moving, but can be quite overwhelming and uncomfortable as well. Sometimes, you get one screen focusing on one subject and the other giving you a wider context of the surrounding scene or environment. I found this duality in the experience quite powerful.

Shirin Neshat: As mentioned earlier, all my films are built around the notion of opposites, and having the two separate projections only adds to that. The audience cannot watch both screens simultaneously, and they become an editor that has to make a choice. When they focus on one screen, they are missing something else on another. I like this idea of forcing the audience to be a true participant and to be drawn in by the device that this film has created, hence becoming a part of the film. This experience can sometimes be quite uncomfortable for the viewer.

Dara: I felt that sometimes we, as viewers, make the decision of where to look subconsciously. We get drawn into a particular scene and want to continue to follow that narrative and subject. I found myself watching parts of the film again because I had completely lost sight of what was happening on the other screen. I think this ability to have a choice to follow what you connect with is quite freeing.

Shirin Neshat: The viewer’s role becomes much more active. They are not just passive recipients of the content; they become engaged participants who are making decisions and interpreting the narrative in their own unique way.

Dara: I want to ask you about some of the other films you worked on, moving onto doing full feature films and switching from black and white to colour.

Shirin Neshat: When I work with a medium for some time, I end up in a place of stagnation, similar to how I felt with photography. Also, I felt a bit exhausted from only working within the art world because everything was more or less focused on commodity, and you were valued based on how much your work was worth. At this point, I received an invitation from the Sundance Film Festival asking if I was interested in making a feature film, and my immediate answer was no. But after reflecting on where I was at that moment with my artwork, I realised that I was at a point where I wanted to take a new risk. This led to Women Without Men (2009), which is based on a book with the same title by Shahrnush Parsipur. It took six years for the film to be made.

I think the opportunity to make feature films was interesting for multiple reasons. One was the ability to connect more with popular culture and to show my work to an audience that may not necessarily know me as an artist from galleries and museums. But for the most part, I wanted to know if I had it in me to make a feature-length film. So, it became an education for me over the years, working with different scriptwriters and learning how I could invent my own language in cinema by borrowing from what I’d done previously in my work as an artist, while fully embracing cinema as a medium.

Although I had received a lot of criticism telling me to stay in art and not to take the risk going into cinema, Women Without Men was quite well received and this motivated me to keep pushing making more feature films. My next project, Looking for Oum Kulthum (2017), was much more difficult because I was making a film in Arabic about an iconic figure in Arabic culture. As a non Egyptian and someone that didn’t speak Arabic, making this film became a tremendous effort. This film became semi biographical and semi artistic, and I wouldn’t say it was fully successful. But I believe none of my work had come without their flaws, yet I never regretted making them.

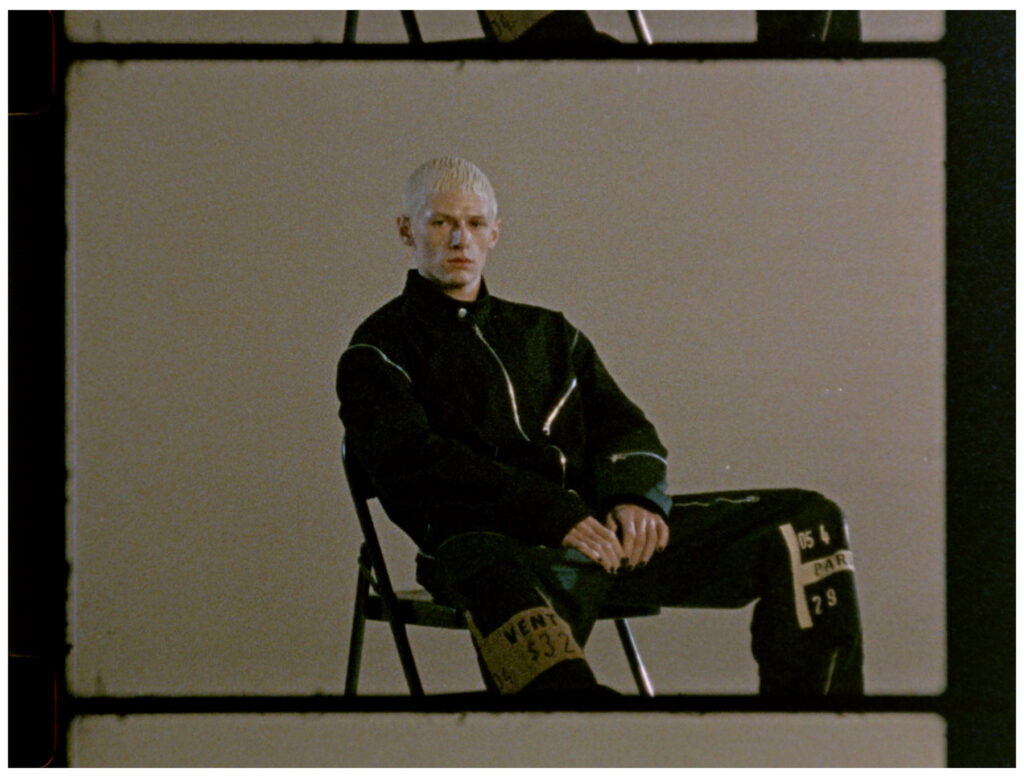

My next feature film was Land of Dreams (2021), which was shot in New Mexico staring Matt Dillon, Sheila Vand, William Moseley, Isabella Rossellini, Christopher McDonald and Anna Gunn, was one of my favourites because I had learnt by this point how to direct and how to think about scriptwriting in a way that I didn’t before. I had the opportunity to work with Jean-Claude Carrière alongside my husband Shoja Azari to create an original story, which was humoristic and based on my own ideas. This process lead to me being very happy with this film, and I never expect to make films that are main stream but for them to be very uniquely a manifestation of a visual artist.

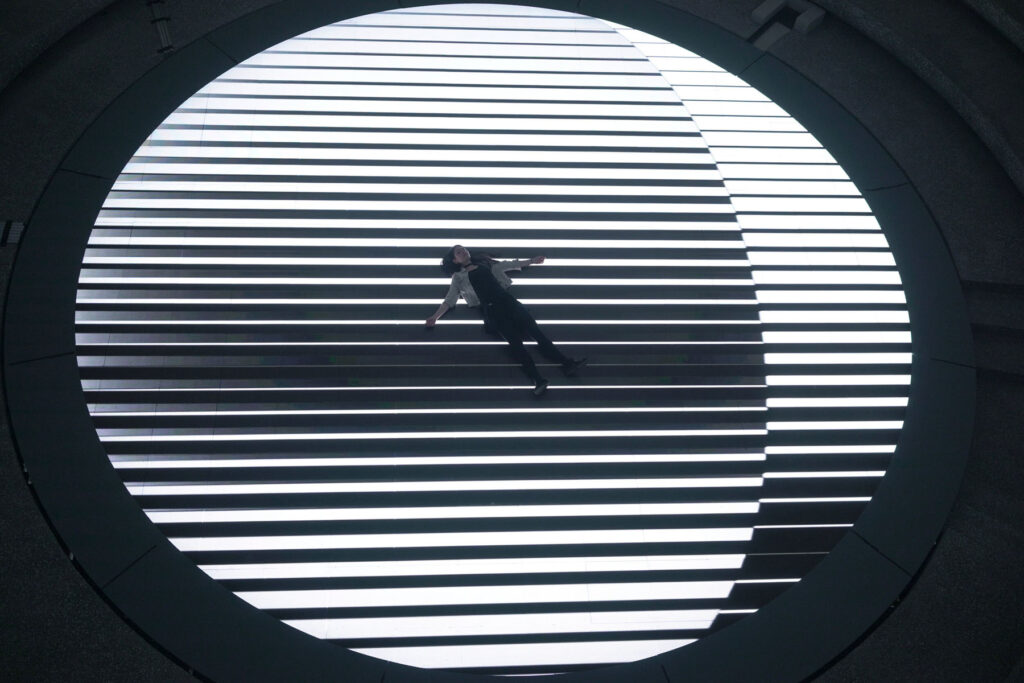

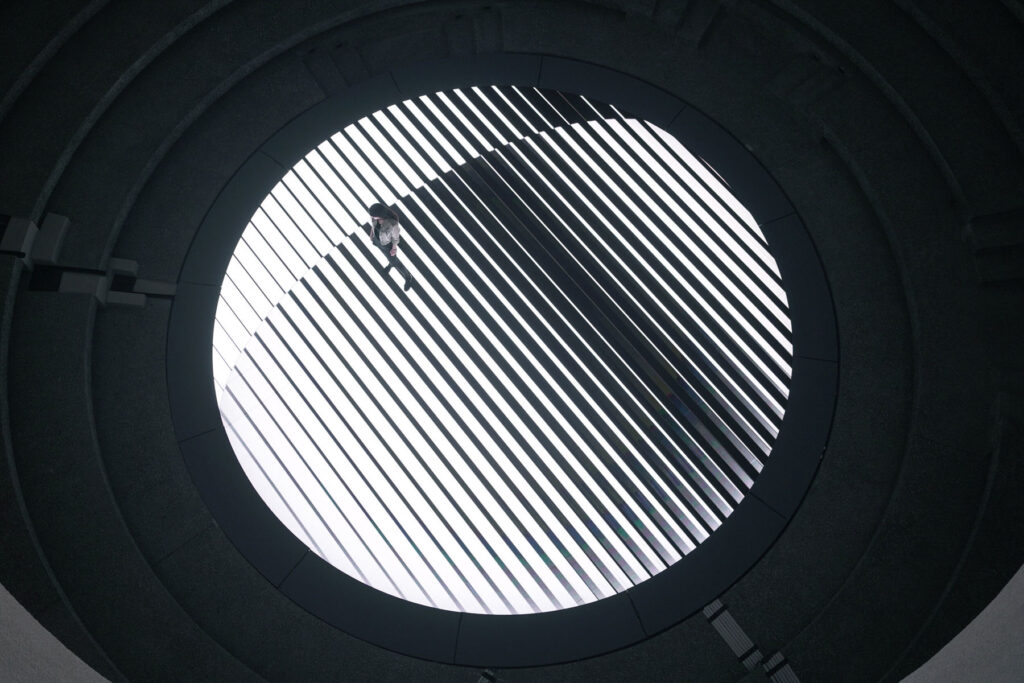

With Land of Dreams, it was the first time that I simultaneously did a feature film, 110 photographs, and a double channel video projection. It all came from my obsession with my own dreams, and followed a three part video project I did two years prior called The Dreamers, which depicted my own nightmares. So Land of Dreams came from taking that obsession and going after other people’s dreams and nightmares. There was a parody about America being the land of dreams; this place where people come to make their dreams into reality, which I believe is true in many ways. I wanted to play with this idea of me going after Americans dreams and collecting them. In doing so, questioning if dreams are a manifestation of our fears, which I believe that they are, and what the subjects are fearful about.

The video that is part of this project involves this strange colony inside of a mountain where all these Iranians are busy analysing Americans dreams. The same actress I worked with in Land of Dreams, Sheila Vand, acts as a spy for the colony, going into a near by town, pretending to be an artist asking American’s whether she can take their photograph, later asking them about their most recent dream, and then taking this information back to the colony.

But with the feature film itself (Land of Dreams), We took it a step further where she (Sheila Vand) is working for the American government’s Census Bureau, and that the Bureau has made a new requirement that, along with regularly requested data, every citizen is asked to share their latest dream. This concept is rooted in my interest in the way governments and corporations are using surveillance to develop an understanding of our subconscious. There is a humoristic but also disturbing side to this film; in the fact that we ourselves are targeted by people in power, whether governments or corporations, to be controlled. Also, the film focuses on a main character who is an Iranian woman and an artist, which is based on myself, that is quite haunted because of personal and political reasons.

Therefore, Land of Dreams ended up being quite layered sociologically in regards to America, but also on a individual level. I think with this film we did well in terms of developing a script or story that is very concise, while having many layers and enigmatic subjects. There is a true balance between humour and absurdity in this film, but also between what our ideas where and what we were able to convey.

Dara: This is a good point to ask you about your latest work The Fury, your process of making this short film and your decision to go back to the two screen installation experience.

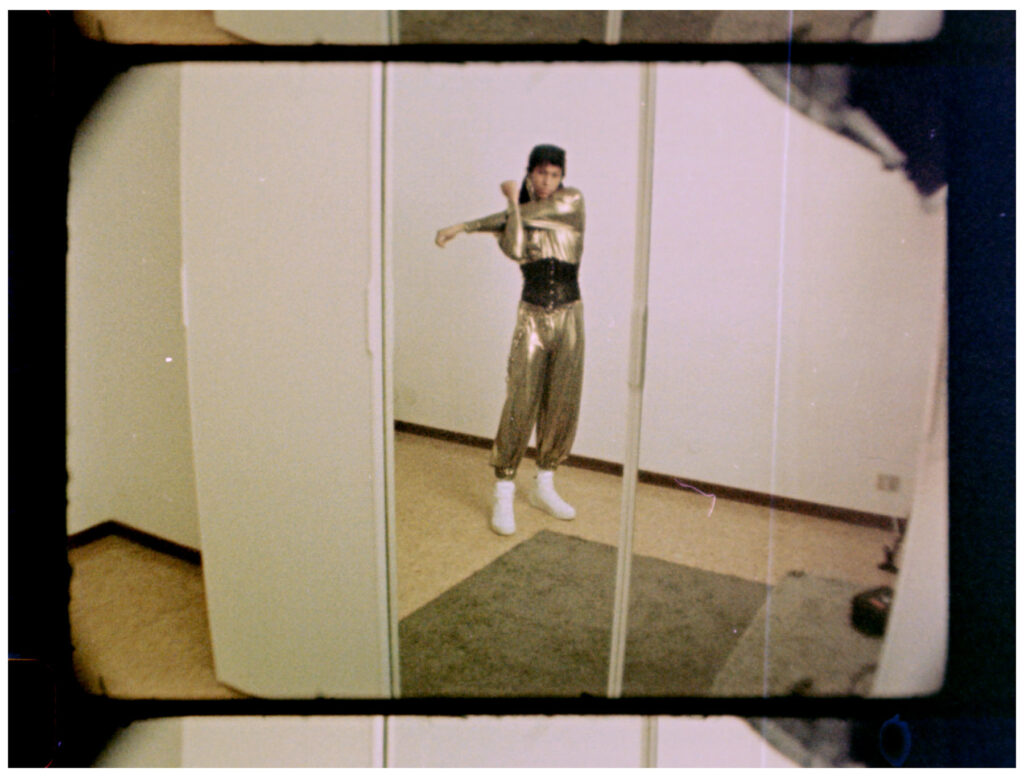

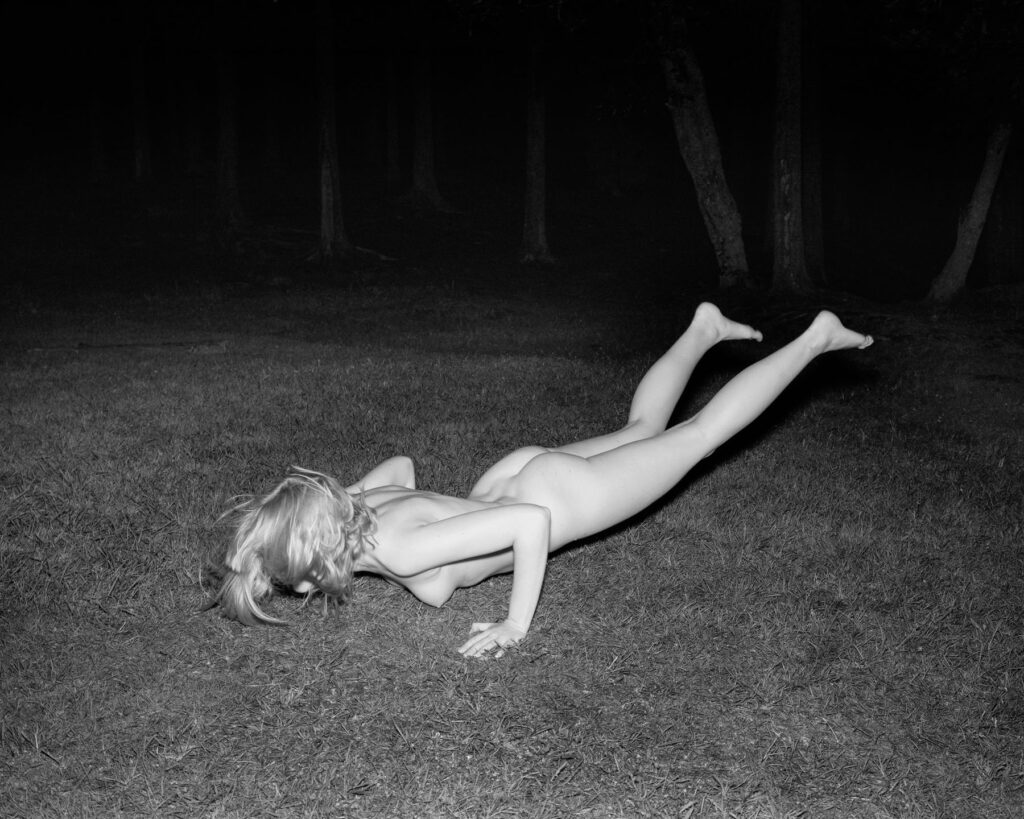

Shirin Neshat: The Fury (2022), in some ways, goes back to the same nature as the Woman of Allah, which is something I tried to stay away from because I knew that if you get close to some of the issues in Iran, people tend to come after you. However, I was influenced by the testimonies shared during Hamid Nouri’s trial in Sweden about women’s experiences in prison, similar to what is being shared today, and how even some of them ended up committing suicide after they were freed. Also, it is important to mention that this film was shot in early 2022 before the recent events that have happened in Iran following the death of Masha Amini, even though many people think this film was influenced by these more recent events. I was very interested and moved by the psychological and mental breakdown of women who are traumatized by sexual exploitation, and due to my consistent focus on the subject of women and how the body of women is used as a space for ideological or religious discourse. In a sense, women are forced to embody the rules of men.

In the case of The Fury, this idea evolves much more into the concept of the women’s body both being the subject of desire, but also of violence and brutality. I wanted to tell a story from the perspective of a person outside of Iran, and the story of a woman who can no longer cope with her reality and goes mad. I referred to my own experience of living among a large Hispanic community in Bushwick, New York, which are hardworking people and come from poor backgrounds. Sometimes, I found myself walking in the streets, listening to Persian music, and feeling like an alien, asking myself what I’m doing here. I experienced this feeling of displacement or disconnection from living among a foreign community, all the while constantly thinking of Iran.

With The Fury, I wanted to create a work that emphasized this experience of displacement, conveying a story of a woman who feels completely out of place as soon as she walks out onto the street, while going mad in her head because of all the traumas she’s dealing with. She’s living inside her own head, and you can get a sense of this early on in the film from her dancing by herself to no particular person. My intention was for the film to progress into a flashback of a trauma where, in order to survive and not be killed, she had to dance nude in front of a male audience – and this is in no way comparable to what women experience while being incarcerated in prison. In the film, the men never actually touch her, but they are brutal in their gaze towards her. When she finally escapes their gaze and runs outside into the middle of the street, she reveals this sense of vulnerability. What is very profound at this point is that all the people on the street who are initially shocked by seeing her outside end up coming to her rescue. This is something I’ve felt in my own neighbourhood; even though the people I live among and I are worlds apart, if anything were to happen to me, these people are my community and would go out of their way to help me because they are good people. To see this community come to her rescue and it turning into a form of protest or dance, in an uncanny way, is exactly what happened after Mahsa Amini’s death. Her death became an impetus for the unleashing of other people’s rage because we’re all angry and we’ve all experienced some form of injustice. Therefore, it is an opportunity for everyone else on the street to also express their pain and anger, turning the scene into this fury. For me, it was about how the pain and suffering of a single human being can be contagious, unleashing our pain, and that we are all ultimately part of one humanity. Many of the people cast in this scene are my friends and members of my community, making this project quite personal to me.

I didn’t want to create a work that tells you what is right or wrong, but I wanted this work to place emphasis on the idea of power, the male gaze, and the vulnerability of this fragile body. The idea that we can all be fragile in the hands of power, but when bad things happen to certain people, it affects others as well and that is our greatest weapon. I received criticism for the assumption that I was labelling all women as victims, and I do not believe in the notion that all women are victims. However, Mahsa Amini was a victim because she was killed and all the other women imprisoned or killed are victims. That is the reality, but the other reality is that we respond to that because it is unjust and unacceptable.

I believe that The Fury has a very bright light at the end of the tunnel, meaning the connection between people, no matter where they come from in the world. Even though they may not fully understand what has happened to her, it causes them to come together in solidarity with her.

Dara: Shirin, I want to finish by using this opportunity as a platform to ask you to share a message with women, especially Iranian women, that are practicing art and are pursuing their creative journeys today.

Shirin Neshat:Firstly, I believe that art shouldn’t be anything else than an obsession that you are at its service. Secondly, I often think about liking myself more when I’m vulnerable, and not liking myself when I’m not. I think it is important for women to allow themselves to be vulnerable, and look at their vulnerability in a positive light because by doing so you are more truthful and can make art that is more truthful as well; art that leads to other people seeing their own vulnerabilities in your subjects. Unfortunately as Iranian women we’ve had so many setbacks, and when we make art there are so many expectations and judgements towards us. Therefore it is so important for us to go within and connect with our internal world, and not care too much about the external world. This is a way for us to check what is so pressing within ourselves to bring out and share with the world, and if there isn’t anything at that moment we shouldn’t do so. Leading to my final point, I hate to say it but mediocracy is the worse of it all and we don’t need to contribute to mediocracy. It must be work that we absolutely feel the need to do and bring out because it has something significant to say and is asking us to be brought out into the world. Otherwise, be patient and don’t rush it.

Dara: I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for being a part of this issue with us. It has been a pleasure to have this conversation with you, and I hope it will move and inspire our readers the way it has done so for me.