«We recognise the past, present, and future but it makes me think perhaps there is a beyond»

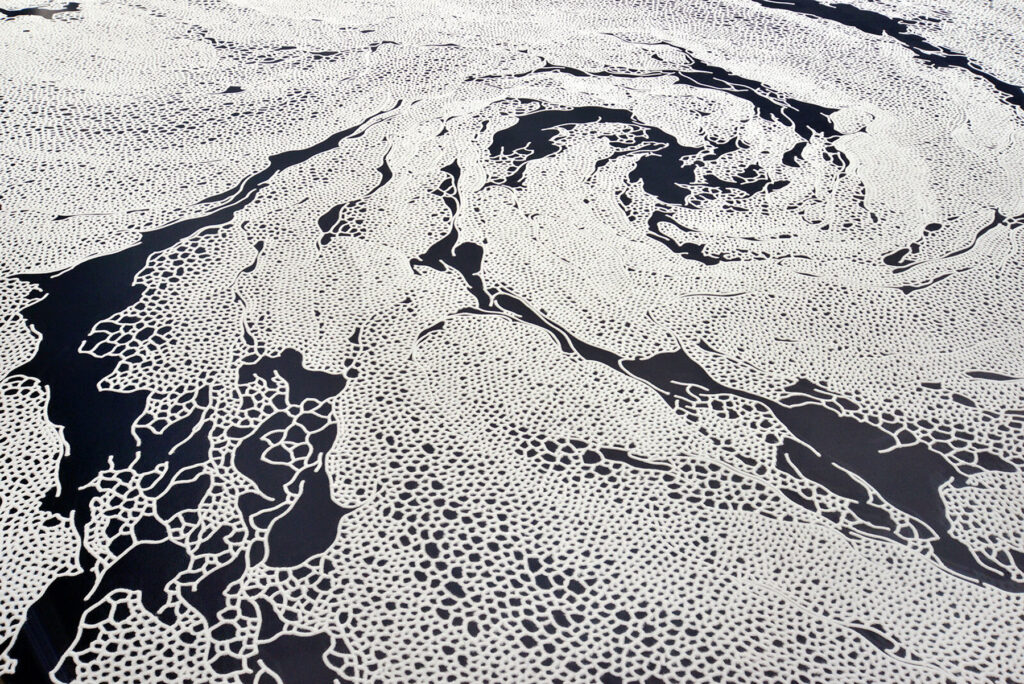

Ghostly white flowers float gently against a sea of black. Delicate pale fish weave their way through the waving fronds of these transparent florae. Luna Ikuta creates these mystical aquatic landscapes by stripping away the colour and chlorophyll from living plants. This process involves “extracting the living cells from plants while leaving the ECM (extracellular tissue matrix) intact.” The flowers are then submerged underwater which causes them to sway softly mimicking the movement caused by light breezes in the natural world.

Ikuta’s aim was to de-sensationalise peoples perception of the outside world by showing them the wonders that could be found in their immediate surroundings. The flowers she used were found on walks around her home in Los Angeles. By transforming them into translucent wraithlike forms these artworks evoke the image of ‘reincarnated spirits’ whilst allowing people to marvel at the natural structures found in their local environments. NR Magazine joined the artist in conversation about her work.

With your botanical artworks, how long does the process of stripping away the living cells of the plants take? And how long does the ECM (extracellular tissue matrix) last once you have completed this process?

Each plant behaves differently but on average it takes about three weeks. Even though completing a tank arrangement from start to finish takes about a month to create, the transparent gardens are all ephemeral works. These installations eventually disintegrate and disappear after about six months. The works are filmed shortly after they are installed and embalmed as digital relics.

You have stated that you believe black to be the richest of all colours. Is that why you have chosen to use exclusively black backdrops with all your botanical artworks?

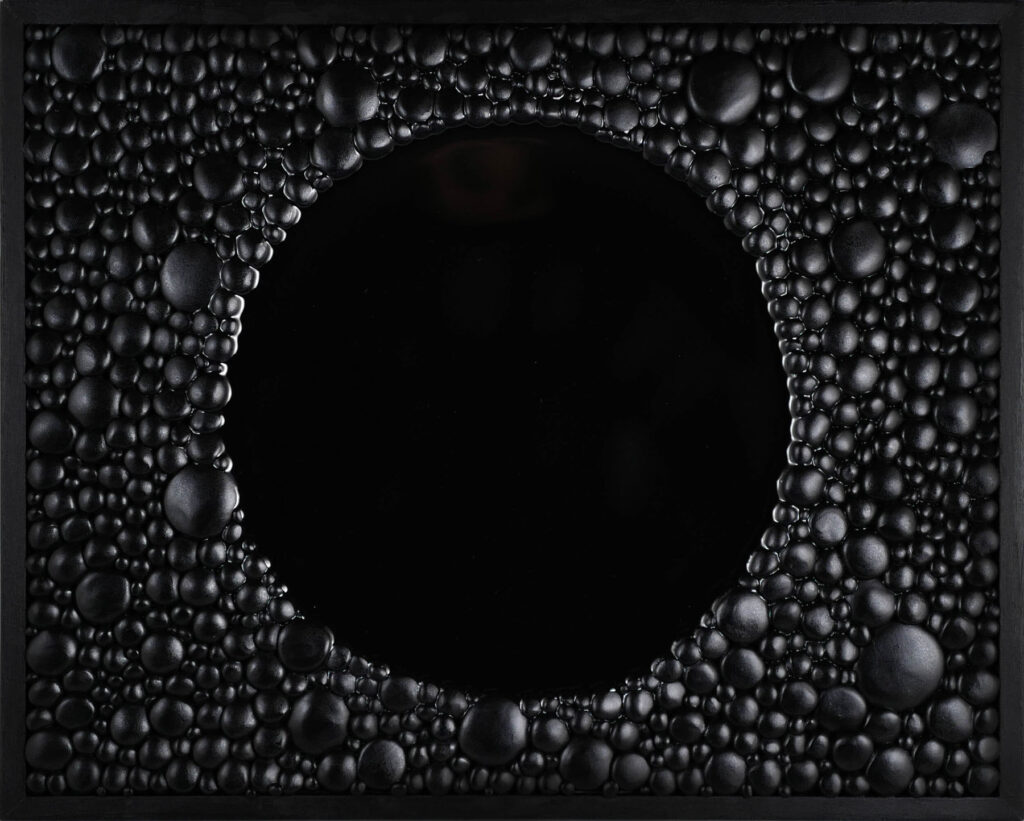

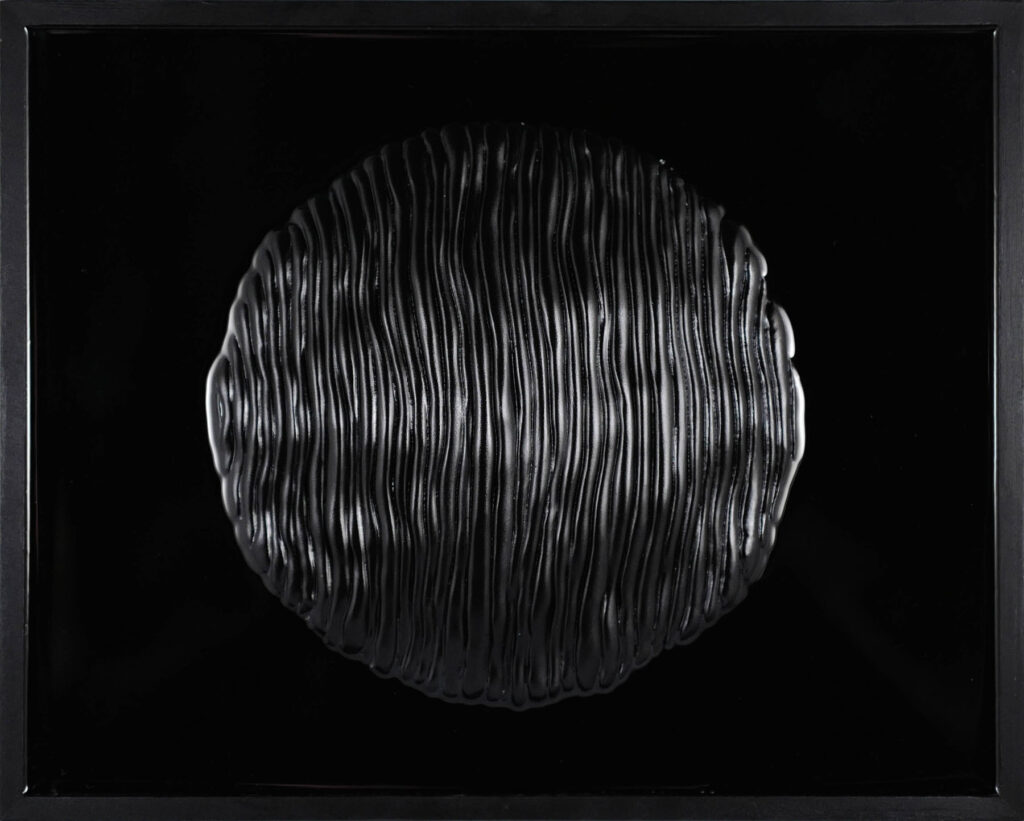

I like using monochromatic palettes in a lot of my works across various mediums. In my sculptural works, I am obsessive about texture and am drawn to muted palettes for I feel excessive color distracts from form and adds unnecessary noise. These botanical works are also an extensive study of texture and form. Each plant was made transparent using a process revealing intricate vascular networks and structures otherwise invisible to our eyes. In these artworks I want the focus to be about the subject and to transport the viewer into an otherworldly space illuminated solely by the ghostly flora.

You stated that you are inspired by Japanese culture. Was there any particular aspect of this culture that influenced your botanical works?

I was born in Tokyo, Japan but was raised in the US. I travel back to Japan to visit relatives every year and grew up in a bilingual household. As I’ve grown older I realise this is my particular advantage to always be living between those two worlds. For that reason, it’s not too important for me to identify with one or the other when it comes to my work because I am just me. The Japanese inspiration comes more from a place that’s difficult to express in words.

«I am mainly interested in making work that connects to the human spirit.»

Do you think there is an intrinsic link between art and science that people tend to overlook as there is a tendency to view the two fields as separate?

As a multimedia artist I’m interested in material science, so I have always seen an intrinsic link between the two. I believe art benefits from science when trying to create experiences that are foreign to everyday life. The science behind the process of creating the Afterlife series also plays a role in the narrative of the work. These artworks combine sculpture, digital media, chemistry, and biology to create an experimental installation that transforms our natural world. The plants are no longer alive but are preserved as ghostly skeletons in the liminal space between life and death. This art practice is also an ongoing experiment. I never know the result of the clearing process for each plant and sometimes it doesn’t work out. This creates challenges and discoveries that propel new ideas and I am always learning.

You have a background in industrial design, how does that inform your art practice?

Industrial design covers a very wide spectrum of trades. What I value the most from this background is that I know how material things are made. I am very hands-on and have experimented with everything from woodworking, metalsmithing, ceramics, 3D modelling, architecture, etc. By having a foundational understanding of various production processes I can be autonomous and it’s very freeing. As an independent artist, every project has my hands on it from the finished artwork, documentation, to building out entire showrooms. My practice ranges from sculpture, installations, furniture, digital media, and now aquarium art. The biggest challenge is answering «what kind of art do you do?» since my methods of making are always changing per project.

Would you ever consider taking other biological forms than plants and stripping away their living cells to create artworks?

I have only scratched the surface of the botanical world using this process and there are so many more plants I would like to work with. I started to see that once you remove the plants from their natural context, they can transform into something entirely different from their original character. In one of my tanks, I placed Chrysanthemums, Sunflowers, and Queen Anne’s Lace as the foreground of the landscape and they resembled very close to sea anemones. Grass looks like aquatic snakes, and some plants look like clams when placed in a specific way.

«Nature has a beautiful way of effortlessly mimicking other life forms in ways I never noticed, and this space is more interesting for me to play with.»

Some of your works involve live fish. How do you deal with the practicalities and ethical concerns of using live animals in your artworks?

My pet Bettas! As a practicing aquascaper, I have experience in monitoring water conditions to make it safe for fish. They are beautifully majestic creatures and I am grateful for their involvement in my films.

Do you think people have become more appreciative of nature due to covid and subsequent lockdowns and if so how is that reflected in your botanical works?

During lockdown, all I did was go on walks outside. It seemed like my friends were all doing the same. Social media was depressing, and the news was even more depressing! On these daily walks, I would observe flowers blooming on the hillside of my house and these subtle changes in the landscape became my elusive «pandemic clock» measuring time. I enjoy watching the life cycle of nature because it’s a quiet but hopeful message. Flowers bloom and wilt but come back again next season. We recognise the past, present, and future but it makes me think perhaps there is a beyond. If so, I wonder if death is really something we have to fear? A lot of my work uses plants that are foraged from my immediate surroundings, so despite awful 2020 I am thankful for the time I had to fully immerse myself into California’s nature.

What advice would you give to young creatives who are interested in combining art and science?

You don’t need to be a scientist!

Are you working on any projects at the moment and what plans do you have for the future?

Yes! I am currently exhibiting these works, AFTERLIFE, at The Transparent Garden which is both my studio and showroom. This gallery showcases eight physical aquaria, each paired with a custom-built LCD screen preserving the video form as collectible art objects. This show was the first time I had shown the physical tanks to the public. I am also releasing a series of NFT’s of the filmed aquariums that will be released on Superrare July 5th. AFTERLIFE ends on June 13th but I really enjoyed meeting everyone who came by the space and I am excited to continue using this gallery as my experimental playground. I am also installing my first permanent public arts sculpture in Los Angeles. I have been working on that piece for over a year so I am excited to see it finally rest on site. Oh and Daruma 2022!

Credits

Images · LUNA IKUTA

https://www.lunaikuta.com/