“We human beings have emotions and we also have something we can’t explain with words – it’s cool, it’s beautiful and it’s fun”

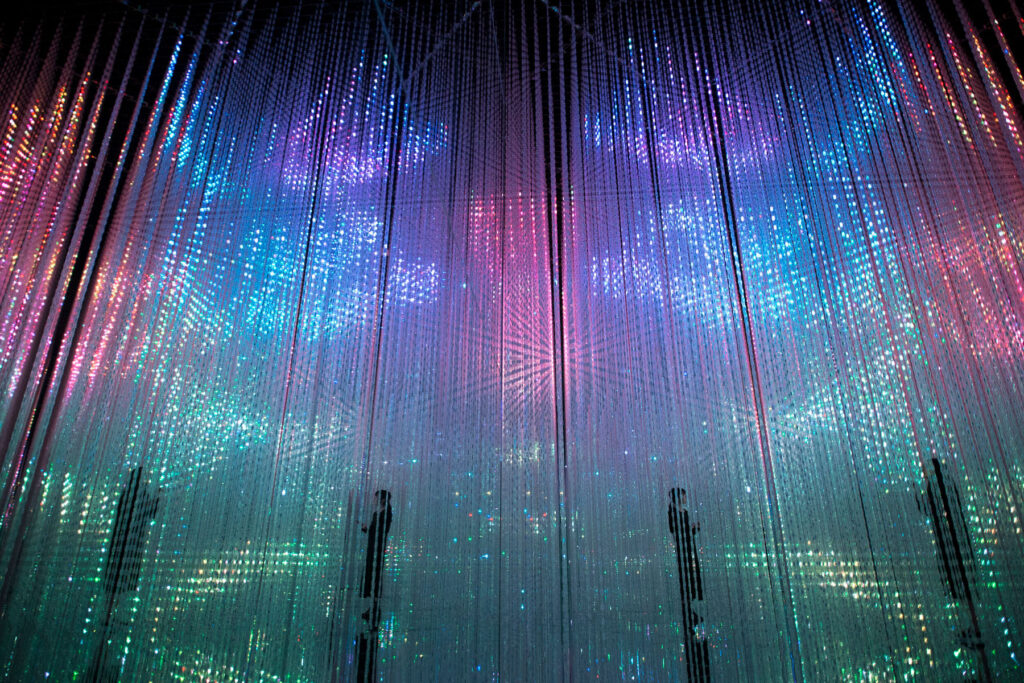

Brightly coloured flora paints itself across the heads of gallery visitors while children, and sometimes adults, chase otherworldly fauna as they dance across the walls of the space. You might walk into one room and find yourself knee-deep in water, projections of vibrant carp swimming around your legs. Walk into another and you are surrounded by green lily pads, some as tall as your head. One thing for sure is nothing is ever the same, and you never quite know what you can expect to find in each room, in each exhibition.

Make no mistake, while teamLab was first formed in Japan in 2001 by Toshiyuki Inoko and a group of his friends, it is now an international art collective made up of “an interdisciplinary group of various specialists such as artists, programmers, engineers, CG animators, mathematicians and architects whose collaborative practice seeks to navigate the confluence of art, science, technology, and the natural world.”

Transcending boundaries is a key concept for teamLab as it states that “in order to understand the world around them, people separate it into independent entities with perceived boundaries between them.” Digital technology allows people to express themselves creatively in a way that is free from physical constraint and the boundary between the viewer and artwork can become blurred. NR Magazine joined teamLab in conversation.

Do you consider teamLab’s work as a form of therapy and a way for visitors to navigate the collective trauma of living in a post-capitalist society that imposes a number of boundaries on us?

A: We are not sure what our output is classified as – we only seek to create what we believe in, regardless of the genre it turns out to be.

Art is something we can’t explain with words and history will decide whether our output qualifies as art. If we can change people’s minds, then it’s art. Art raises questions and design provides answers. We human beings have emotions and we also have something we can’t explain with words – it’s cool, it’s beautiful and it’s fun. What our exhibitions do is underpin the impossibility to “have.” None of our visitors can own the artworks: they can’t “have” but they can “be” (following Shakespeare’s immortal quote, “To be or not to be”). Today’s society drives us to “have” which imposes limits and division. This simple structure of capitalism binds us, but the internet and the digital world beyond have no limitations. At the same time, you don’t technically own anything on Google or Facebook, but you are part of the community. Therefore, you can’t “have” but you can “be.” Our artwork is shared the same way. We wanted to make something that will reach people’s hearts.

teamLab encourages visitors to interact with the artworks and capture their experiences for social media. However, do you think there is a danger of people focusing too much on getting the ‘perfect shot’ and not truly experiencing the work?

A: We don’t “encourage” people to use social media.

But at the same time, we think that the act of expressing oneself is not a bad thing.

Shooting photos or videos and even sharing those with people all over the world is also one mode of self expression, right?

It is a natural human desire to share emotions or something that is moving and inspiring. However, the “experience” cannot be cut out.

Through smartphones or TVs, people can understand only with their heads. Knowledge may be gained, but the sense of values and perceptions cannot be changed or broadened. Only through the actual, physical experience of the world or artworks, people can start to recognise things differently. Even if people look at teamLab’s works on Instagram, their values will not be broadened.

teamLab wants to continue creating experiences that cannot be shared with just photos or videos.

Our interest is not the technology itself, but instead, we’re trying to explore the concept of “digital” and how it can enhance art.

Most of the Silicon Valley-originated technology is an extension of someone’s mind. Facebook, Twitter, these digital domains see the “self” as the principle. These are meant to be used personally.

What teamLab wants to do is to enhance the physical space itself using art. It doesn’t necessarily have to be yourself that intervenes with it. It can be other people or a group of people that vaguely includes you. And instead of a personal use, we want to make it usable by multiple people.

By digitising the space, we can indirectly change the relationships between people inside. If the presence of others can trigger the space to change, they’d become a part of the artwork. And if that change is beautiful, the presence of others can be something beautiful as well. By connecting digital technology and art, we think the presence of others can be made more positive.

How has the pandemic affected the collective and has it changed how teamLab approaches exhibiting art?

A: Right now, we are isolated due to our fear of the virus. But in order to overcome that, whether you are in lockdown or not, we hope to encourage you to realise that there never are and never were boundaries, that we are connected to the world just by existing in it, and that we don’t have to try to connect with others by rejecting them.

The fact that we can connect with each other, regardless of where we live or anything else, is a message that affirms human existence from the ground up. We would be happy if humans could accidentally connect with others and derive positive value from that.

Humanity has faced many problems over its history, but we do not believe that these problems have ever been solved by division.

The birth of civilised nations and the spread of infectious diseases were both the result of globalisation and the loss of world boundaries, but humanity has solved this problem not by dividing people, but by working together to develop drugs and vaccines, advance medical technology, and improve sanitation.

We believe that people need to remember the benefits of history and science because if we only look superficially at the immediate events of the current coronavirus pandemic, we promote emotional division.

Art and culture have expanded humanity’s “standards of beauty.” Art presents a new standard of beauty that has changed the way people see the world and, to put it plainly, has allowed them to see flowers as beautiful. teamLab’s artworks are also designed to help people experience the beauty of a world without boundaries and the beauty of anti-division.

Humans are driven by beauty. Corporate organisations seem to be driven by logic and language, but when we look at individuals, they often determine their actions based on their sense of beauty. For example, a person’s choice of a profession is heavily influenced by aesthetics, not rationality. The way in which “standards of beauty” are applied changes a person.

Everything in the world is built on a borderless, interconnected continuity. We believe that human beings should be celebrated for being connected to others and to the world and that experiencing a “world without boundaries” can change our values and behaviours and help us to move humanity in a positive direction.

This is a fundamental affirmation of human life.

We have created an artwork that allows people to experience being connected to others and the world, even in the comfort of their homes. Flowers Bombing Home is an artwork that transforms the television in your home into an artwork. The novel coronavirus has forced the world to become more isolated, causing people to become confined to their homes. This project was created to help us realise that our existence is connected to the world and to celebrate the fact that the world is connected.

However, as we mentioned, we believe that our art is meant to be experienced in person in a shared, physical space. So as the world opens up again, we are excited to welcome visitors back into our exhibitions, where they can explore the continuity of life and time.

Are there any new technologies that teamLab is particularly excited about and is planning on incorporating into the artwork?

A: Technology is just a tool, like paint.

Although it’s a tool, it does greatly affect the creation, just like how the Western landscape painting developed because it became possible to bring paints outdoors.

What really makes teamLab unique is not the technological advancement, but rather the fact that teamLab has become able to do truly massive art projects simultaneously worldwide in-house at a high speed – to the extent that no one has been able to do before.

We could say that technology is the core of our work, but it is not the most important part. It is still just a material or a tool for creating art.

We have been creating art using digital technology since the year 2001 with the aim of changing people’s values and contributing to societal progress. Although we initially had no idea where we could exhibit our art or how we could support the team financially, we also strongly believed in and were genuinely interested in the power of digital technology and creativity. We wanted to keep creating new things regardless of genre limitations, and we did.

Digital technology allows artistic expression to be released from the material world, gaining the ability to change form freely. The environments where viewers and artworks are placed together allow us to decide how to express those changes.

In art installations with the viewers on one side and interactive artworks on the other, the artworks themselves undergo changes caused by the presence and behaviour of the viewers. This has the effect of blurring the boundary lines between the two sides. The viewers actually become part of the artworks themselves. The relationship between the artwork and the individual then becomes a relationship between the artwork and the group. Whether or not another viewer was present within that space five minutes before, or the particular behaviour exhibited by the person next to you, suddenly becomes an element of great importance. At the very least, compared to traditional art viewing, people will become more aware of those around them. Art now has the ability to influence the relationship between the people standing in front of the artworks.

You have created an interactive at-home art installation, that people can access around the world, can you tell us more about that work?

A: The novel coronavirus has forced the world to become more isolated, causing people to become confined to their homes. This project was created to help us realise that our existence is connected to the world and to celebrate the fact that the world is connected.

The television in your home becomes art. Watch at home, participate at home, and connect with the world. People from around the world draw flowers, creating a single artwork that blooms in homes around the world.

Draw a flower on a piece of paper, your smartphone, or computer, and upload it. The flowers you draw and the flowers drawn by others bloom and scatter in real time on the YouTube Live Stream. If you connect your home television to YouTube, your television turns into art. As the petals scatter, the various flowers form a single new artwork together.

When a new flower is born, the name of the town where the flower was drawn is shown.

You can also download Your Flower Art, which combines the flowers you draw with those drawn by people around the world.

The flowers that people draw around the world will bloom until the end of the coronavirus. When the coronavirus ends, they will bloom and scatter all at once in various places all over the world. And, in the future, perhaps the flowers will continue to bloom forever as an artwork for people to remember this era.

It is stated that teamLabs work fuses together art and science but can you ever really have one without the other?

A: We have always liked science and art. We want to know the world, want to know humans, and want to know what the world is for humans.

Science raises the resolution of the world. When humans want to know the world, they recognise it by separating things. In order to understand the phenomena of this world, people separate things one after another.

For example, the universe and the earth are continuous, however, humans recognise the earth by separating it from the universe. To understand the forest, humans break it down into trees, separating the tree from the whole. Humans then cut the tree into cells to recognise the tree, cut the cells into molecules to recognise the cells, and cut the molecules into atoms to understand the molecules, and so on. That is science, and that is how science increases the resolution of the world.

But in the end, no matter how much humans divide things into pieces, they cannot understand the entirety. Even though what people really want to know is the world, the more they separate, the farther they become from the overall perception.

Humans, if left alone, recognise what is essentially continuous as separate and independent. Everything exists in a long, fragile yet miraculous continuity over an extremely long period of time, but human beings cannot recognise it without separating it into parts. People try to grasp the entirety by making each thing separate and independent.

Even though we are nothing but part of the world, we feel as if there is a boundary between the world and ourselves, as if we are living independently. We have always been interested in finding out why humans feel this way.

The continuity of life and death has been repeated for more than 4 billion years. However, for humans, even 100 years ago is a fictional world. I was interested in why humans have this perception.

How can we go beyond the boundaries of recognition? Through art, we wanted to transcend the boundaries of our own recognition. We wanted to transcend human characteristics or tendencies in order to recognise the continuity.

Art is a search for what the world is for humans. Art expands and enhances “beauty.” Art has changed the way people perceive the world.

Groups move by logic, but individuals decide their actions by beauty. Individuals’ behaviours are determined not by rationality but by aesthetics. In other words, “beauty” is the fundamental root of human behaviour. Art expands the notion of “beauty”. Art is what expands people’s aesthetics, that is, changes people’s behaviour.

It may be the whole world or only a part of the entirety, but it is art that captures and expresses it without dividing it. Art is a process to approach the whole. And by sharing it with others, the way people perceive the world changes. Through the enjoyment of art, the notion of “beautiful” expands and spreads, which in turn changes people’s perceptions of the world.

Everything exists in a long, fragile yet miraculous continuity over an extremely long period of time. teamLab’s exhibitions aim to create an experience through which visitors recognise this continuity itself as beautiful, hence changing or increasing the way humans perceive the world.

So we can say that there is no boundary between science and art in our activity. Both of them are ways in which to recognise the world, and both are important to our aim.

Is there a specific teamLab work that stands out from the rest and if so why?

A: Our most recent works often stand out because our output is a result of accumulated knowledge and experiences.

But of our many exhibitions worldwide, one that holds a special place in our hearts is the annual outdoor exhibition teamLab: A Forest Where Gods Live in Mifuneyama Rakuen in Kyushu.

The 500,000 square meter Mifuneyama Rakuen Park was created in 1845, during the end of the Edo period. Sitting on the borderline of the park is the famous 3,000-year-old sacred Okusu tree of Takeo Shrine. Also in the heart of the garden is another 300-year-old sacred tree. Knowing the significance of this, our forebears turned a portion of this forest into a garden, utilising the trees of the natural forest. The border between the garden and the wild forest is ambiguous, and when wandering through the garden, before they know it, people will find themselves entering the woods and animal trails. Enshrined in the forest is the Inari Daimyojin deity surrounded by a collection of boulders almost supernatural in their formation. 1,300 years ago, the famous priest Gyoki came to Mifuneyama and carved 500 Arhats. Within the forest caves, there are Buddha Figures that Gyoki directly carved into the rock face that still remain today.

The forest, rocks, and caves of Mifuneyama Rakuen have formed over a long time, and people in every age have sought meaning in them over the millennia. The park that we know today sits on top of this history. It is the ongoing relationship between nature and humans that has made the border between the forest and garden ambiguous, keeping this cultural heritage beautiful and pleasing.

Lost in nature, where the boundaries between man-made gardens and forests are unclear, we are able to feel like we exist in a continuous, borderless relationship between nature and humans. It is for this reason that teamLab decided to create an exhibition in this vast, labyrinthine space so that people will become lost and immersed in the exhibition and in nature.

We exist as a part of an eternal continuity of life and death, a process that has been continuing for an overwhelmingly long time. It is hard for us, however, to sense this in our everyday lives, perhaps because humans cannot easily conceptualise time for periods longer than their own lives. There is a boundary in our understanding of the continuity of time.

When exploring the forest, the shapes of the giant rocks, caves, and the forest allow us to better perceive and understand that overwhelmingly long time over which it all was formed. These forms can transcend the boundaries of our understanding of the continuity of time.

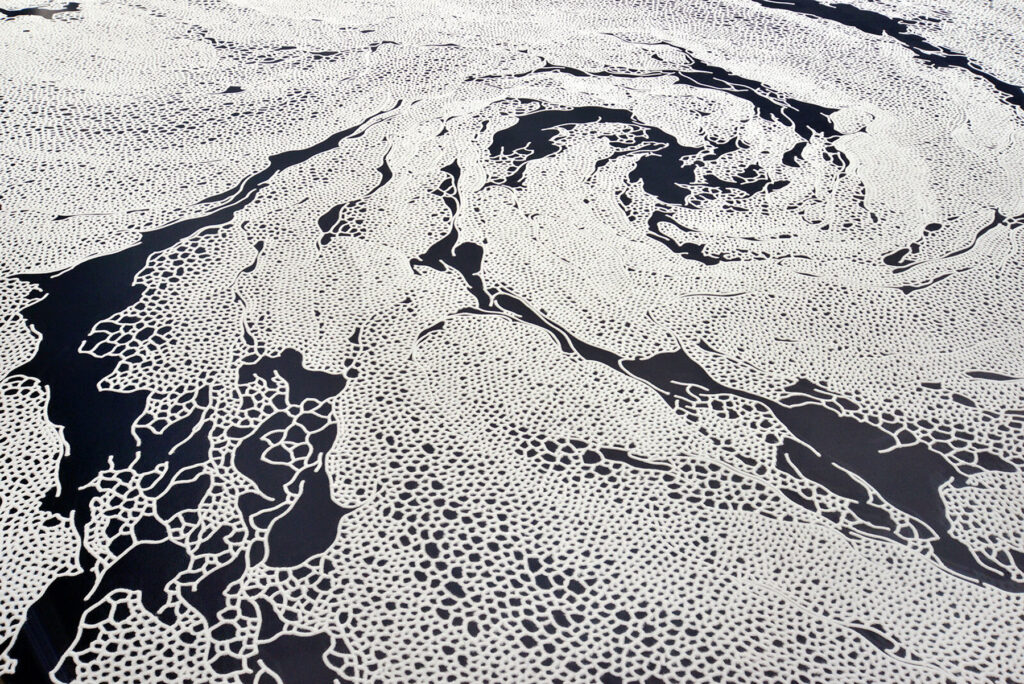

teamLab’s project, Digitized Nature, explores how nature can become art. The concept of the project is that non-material digital technology can turn nature into art without harming it.

These artworks explore how the forms of the forest and garden can be used as they are to create artworks that make it possible to create a place where we can transcend the boundary in our understanding of the continuity of time and feel the long, long continuity of life. Even in the present day, we can experiment with expressing this “Continuous Life” and continue to accumulate meaning in Mifuneyama Rakuen.

Have you found that digital interactive work has become more popular in recent years and if so why do you think that is the case?

A: To be honest, we do not know.

All we can say is that teamLab believes digital technology can expand art and that art made in this way can create new relationships between people.

Digital technology enables complex detail and freedom for change. Before people started accepting digital technology, information and artistic expression had to be presented in some physical form. Creative expression has existed through static media for most of human history, often using physical objects such as canvas and paint. The advent of digital technology allows human expression to become free from these physical constraints, enabling it to exist independently and evolve freely.

No longer limited to physical media, digital technology has made it possible for artworks to expand physically. Since art created using digital technology can easily expand, it provides us with a greater degree of autonomy within the space. We are now able to manipulate and use much larger spaces, and viewers are able to experience the artwork more directly.

The characteristics of digital technology allow artworks to express the capacity for change much more freely. Viewers, in interaction with their environment, can instigate perpetual change in an artwork. Through an interactive relationship between the viewers and the artwork, viewers become an intrinsic part of that artwork.

In interactive artworks that teamLab creates, because viewers’ movement or even their presence transforms the artwork, the boundaries between the work and viewers become ambiguous. Viewers become a part of the work. This changes the relationship between an artwork and an individual into a relationship between an artwork and a group of individuals. A viewer who was present 5 minutes ago, or how the person next to you is behaving now, suddenly becomes important. Unlike a viewer who stands in front of a conventional painting, a viewer immersed in an interactive artwork becomes more aware of other people’s presence.

Unlike a physical painting on a canvas, the non-material digital technology can liberate art from the physical. Furthermore, because of its ability to transform itself freely, it can transcend boundaries. By using such digital technology, we believe art can expand the beautiful. And by making interactive art, you and others’ presence becomes an element to transform an artwork, hence creating a new relationship between people within the same space. By applying such art to the unique environment, we wanted to create a space where you can feel that you are connected with other people in the world.

All we do is create what we believe in – our hope is that our output reaches people’s hearts and changes their ways of thinking or behaviour. Popularity is just a byproduct of that. We never consider popularity when working, all we focus on is creating something we believe in.

What advice do you have for young creatives who are interested in working with digital and interactive works?

A: teamLab was started by a group of friends who simply enjoyed spending time together, and it has continued to grow and change. If you only think in practical terms, logically, you will fail. It is good to start with the things you enjoy in life.

We aim to create artworks and experiences that allow people to experience the beauty of the world with their hearts and their bodies. In the 20th century, we were taught to only understand the world through our “heads,” but it is important to experience things with our hearts and our bodies. Do not think you can understand the world just through the internet.

Is teamLab working on anything at the moment and what plans does the collective have for the future?

A: You can find the information about upcoming exhibitions worldwide on our website – please check there for the latest updates!

Credits

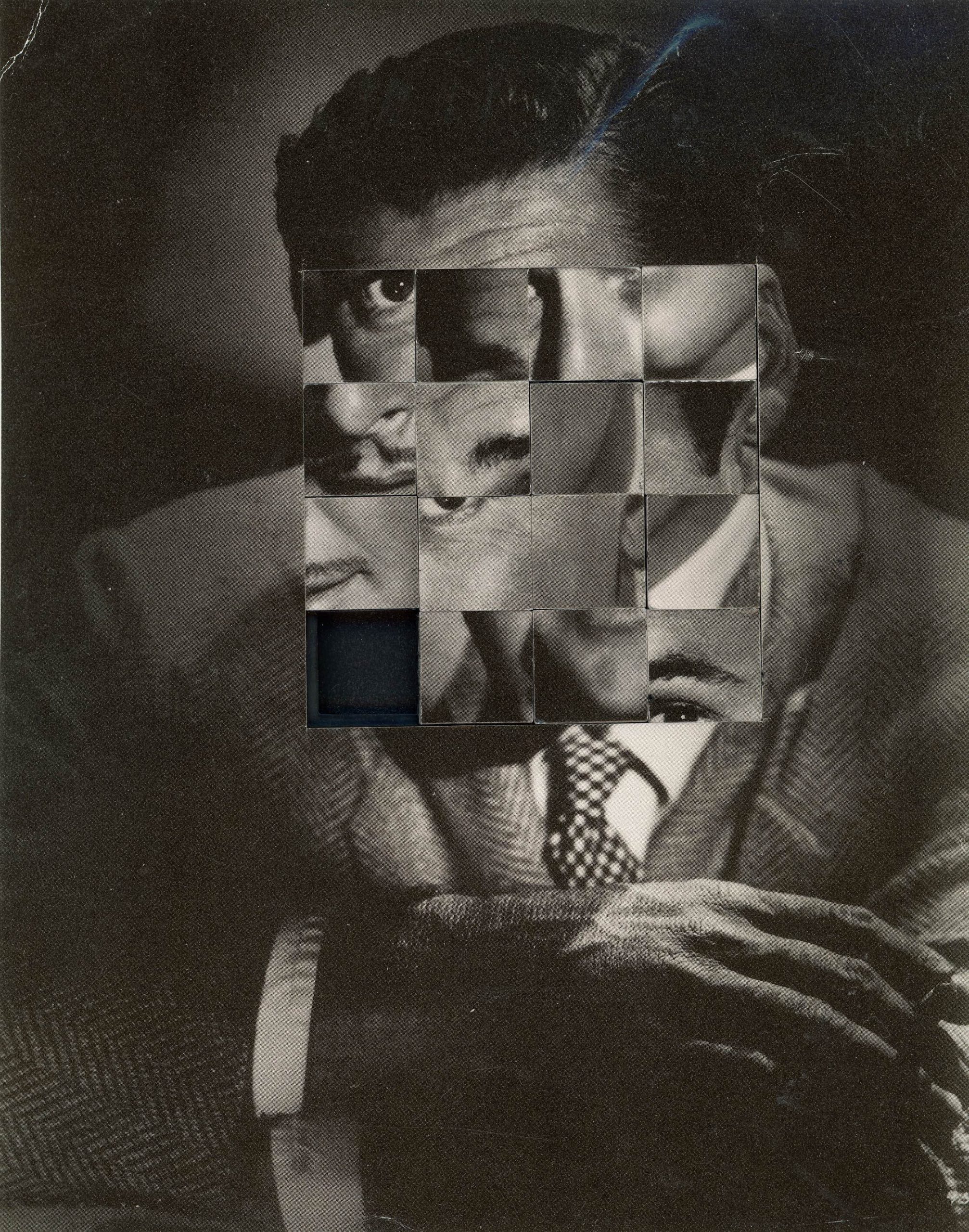

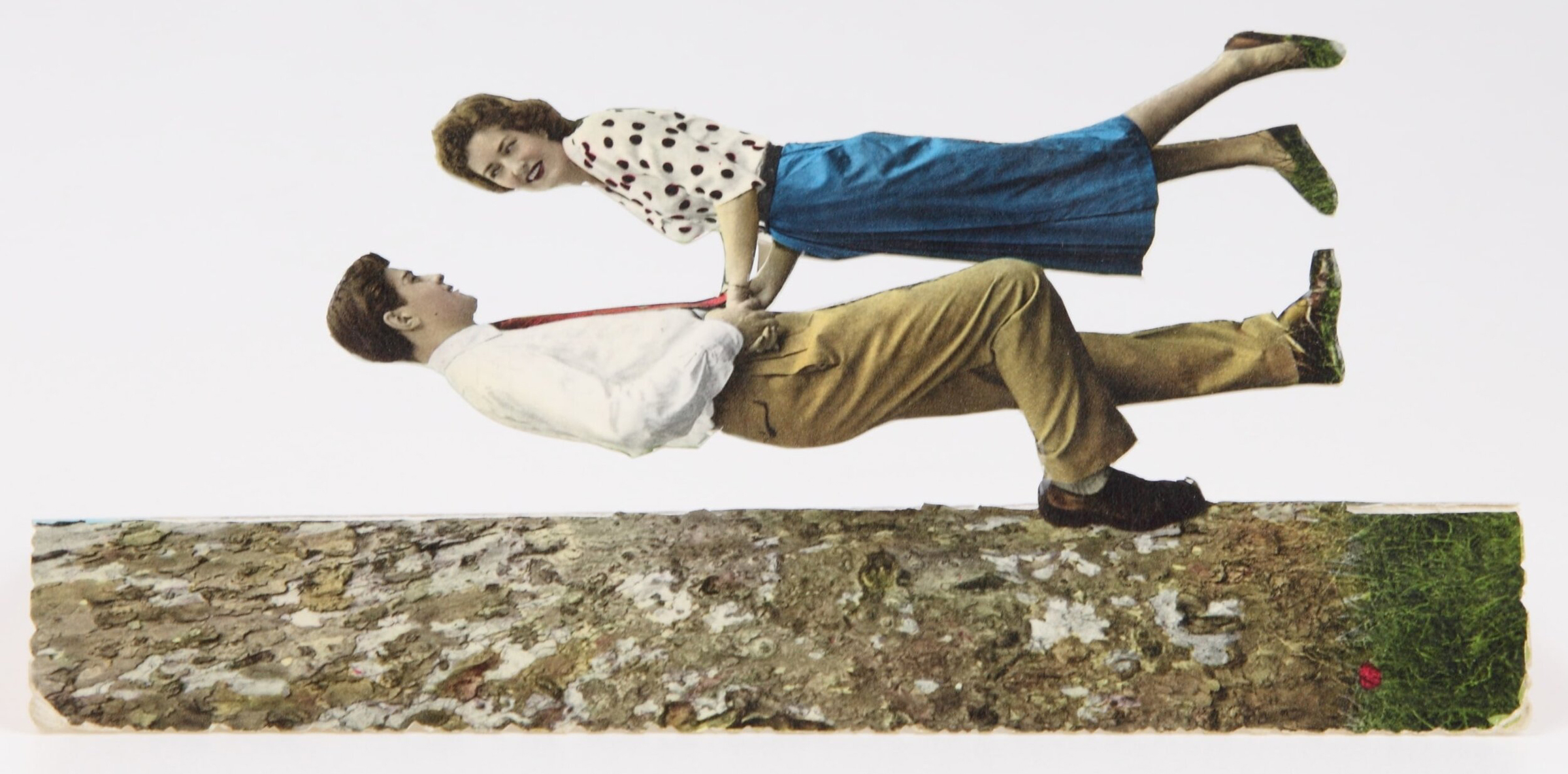

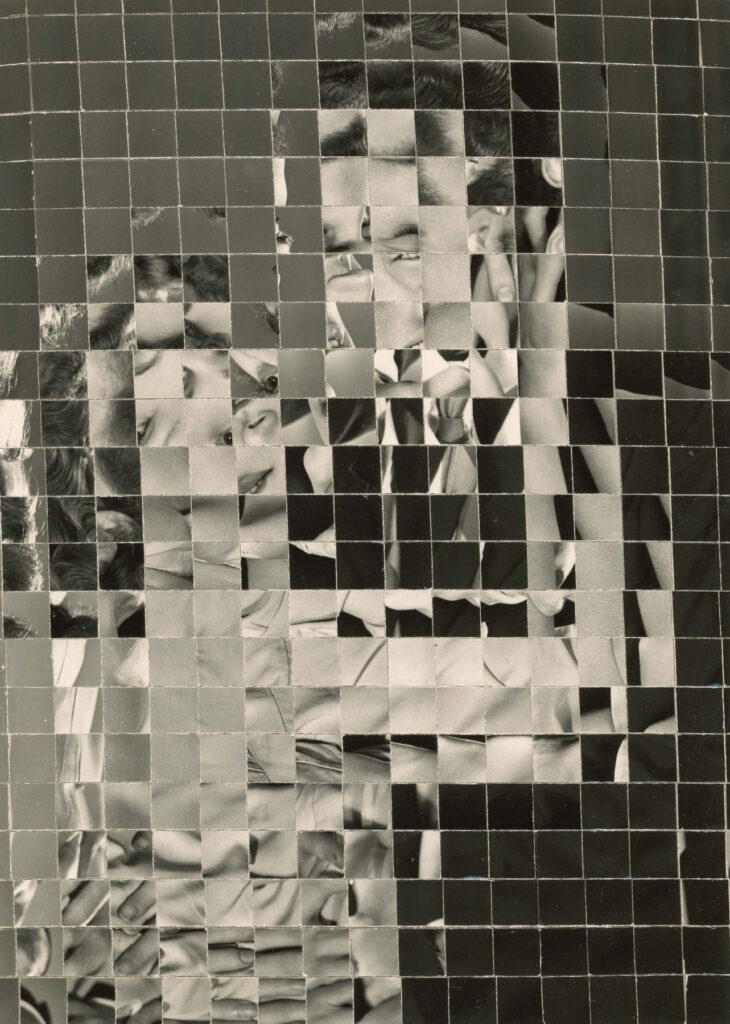

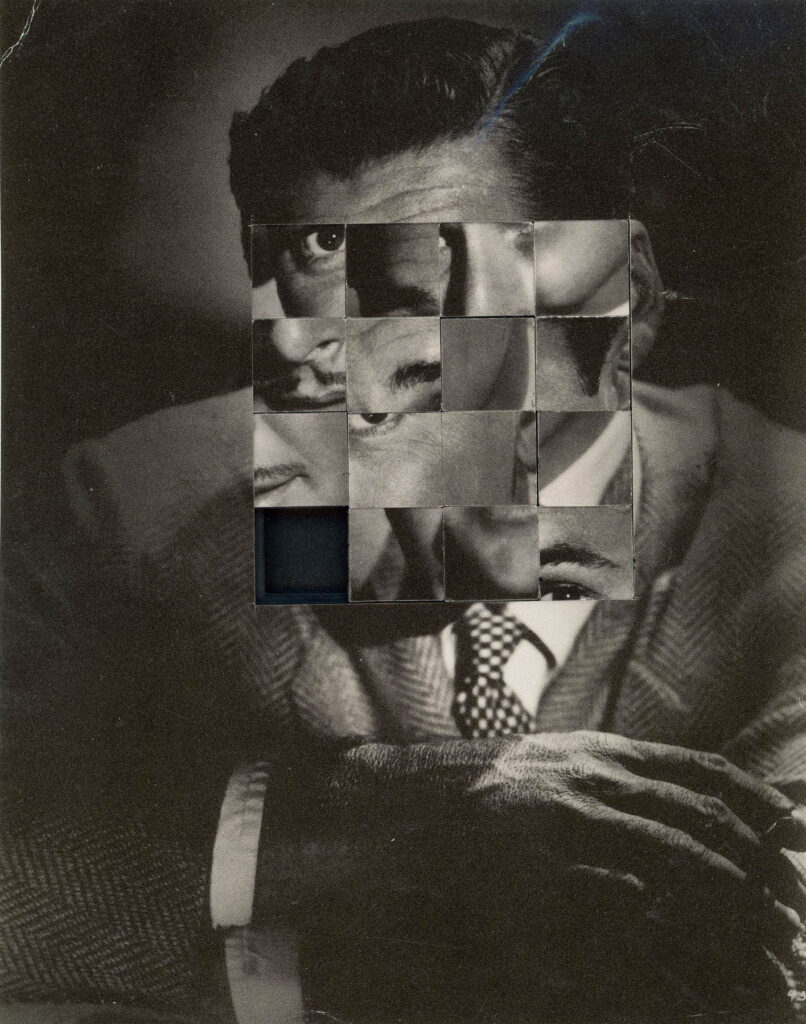

Images · teamLAB

https://www.teamlab.art/