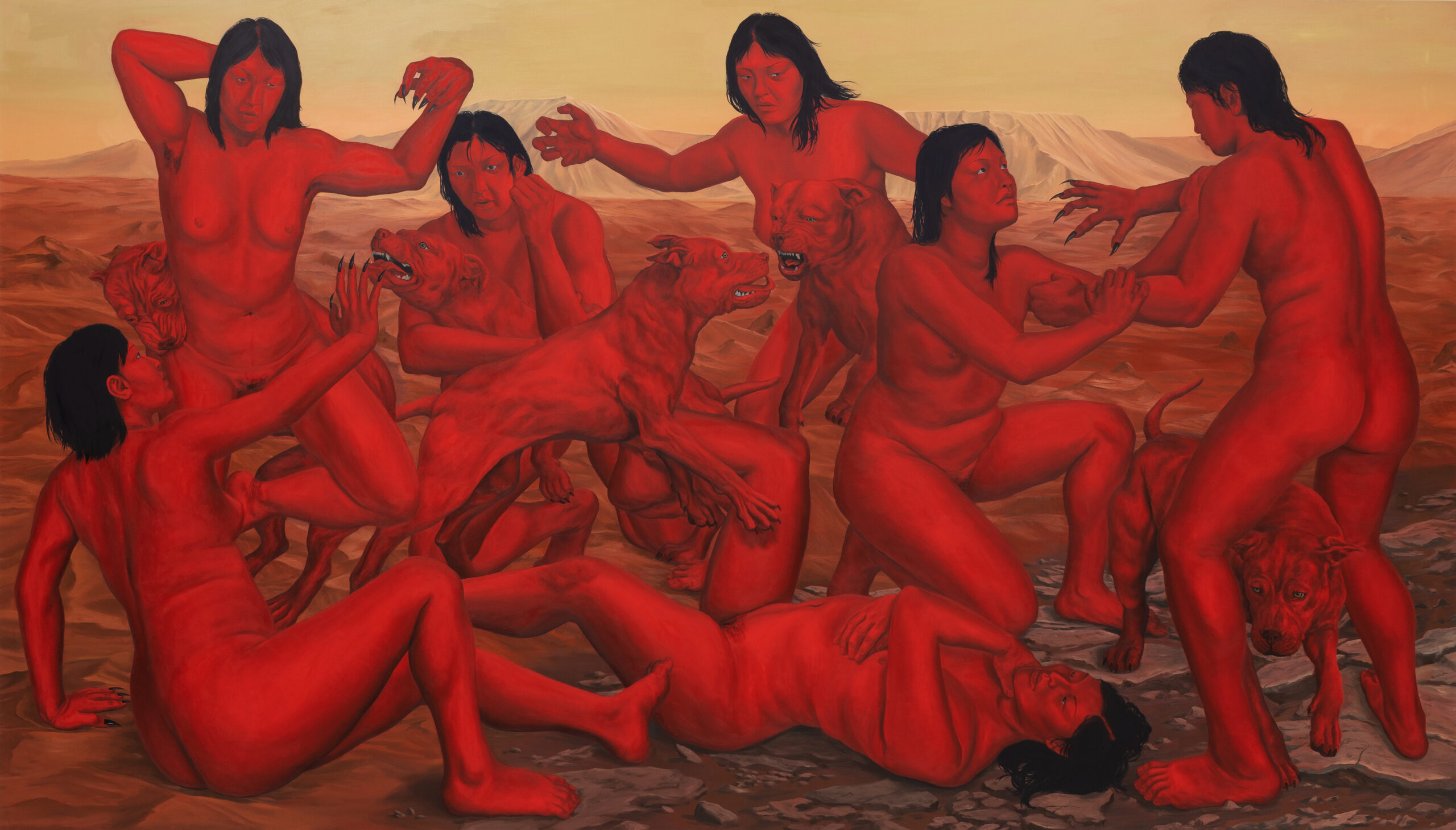

Titanomachia, 2022. Courtesy of PM/AM

Post-humanism, Otherness and diasporic memory

Amanda Ba is a Chinese artist based in New York City. Born in Columbus, Ohio, she spent the first five years of her life with her grandparents in Hefei, China before moving to New York and graduating from Columbia University in 2020 with a BA in Visual Arts and Art History.

Ba’s work is influenced by critical race and queer theory. By utilising these frameworks, she aims to explore more nuanced understandings of identity and examine themes such as post-humanism, Otherness and diasporic memory. Through her art, Ba challenges traditional notions of identity and representation, and creates works that are thought-provoking and impactful. The feeling of attachment and nostalgia and a desire to reconnect to China are influential in Ba’s work. Her goal is not to flatten identity, but to challenge the notion of what it looks like and formulate a more complex way of understanding identity, which creates a tension in her work. Her scenes astray from a larger hypothetical world visualised through her personal narrative imbued of a specific colour code intertwining between red and green. Ba’s use of various mediums, including sculpture and installation, allows her to experiment with different forms of expression.

Guarding Narcissus, 2022. Courtesy of PM/AM

You were born in Ohio, United States but raised by your grandparents in Hefei, Anhui Province, China, until the age of 5. After that, you settled back in Columbus, Ohio. What are your earliest memories being in Hefei? Are there any elements from that time that you like to draw back into your practice?

How did you immerse yourself into the arts, especially within figurative painting?

I have this specific memory of my grandmother dropping me off at preschool for the first time —back then, preschool was just a small, two-room building within the apartment complex where my grandparents lived. When she left and closed the door behind her, I thought that it meant I would never see her again, and dread washed over me. I think I cried all day, until she picked me up and explained that she would always come back to get me.

I also have a lot of memories of food, going to the local science museum, and picking small snails off of garden walls along the sidewalk. Mostly when I think back to that time, I remember a feeling of strong, inseverable attachment to my grandparents. That feeling of attachment, of nostalgia, and wanting to reconnect and re-understand China always factors into my work. I feel lucky that I was able to experience growing up in China, so that I always have an entry point back in.

Drawing was an early hobby of mine that developed when I was in China. My grandfather was an industrial drafter during the Cultural Revolution, so he always had lots of nice paper and pens, and would teach me how to render things in the third dimension. I latched onto the human body pretty early — it has always been a central focus of mine.

You graduated in 2020 with a B.A. in Visual Arts and Art History from Columbia University in New York. What has your major taught you?

Art History taught me how to be intentionally referential with my work, and that there’s always room to rework and redefine the canon. Studying the canon made me realise that perhaps I would rather dwell in the under-commons. It also taught me not only to hone in on the artist’s life, but to contextualise the way they were working within certain political and geographical conditions.

How is the landscape of New York influencing your work? What is your interaction like with the City?

New York is challenging, but it’s a playground. It’s a hard city to live in — even daily tasks are ridden with obstacles — but the challenge keeps me energised. The challenge is fun.

In an interview for Columbia Daily Spectator, you’ve quoted a saying that goes ‘the more words are written about an art piece, the less people see it’. That being said, is there an element within your paintings you would want people to absolutely perceive?

That’s a quote I actually regret saying. Well, maybe not regret, but I did say that in my freshman year, as an 18 year old who didn’t really know what their own work was about. I think because I couldn’t properly verbalise it, I came up with an excuse that left it all up to audience interpretation. Now I write and talk extensively about my work, and I wouldn’t be caught dead saying that. I think that art writing is actually crucial, and good art writing expands on the meaning of the work, rather than telling the audience what to think. Good art writing poses new questions and contextualises the work in a way that makes the audience curious for more, not satisfied with a conclusion.

One thing that I hope people get from my work is that I’m working from a place of tension between representing identity and rendering it unintelligible. I hope that it’s clear that my goal is not to flatten identity by making paintings that are simply about ‘being Asian’ or ‘being an Asian woman,’ but rather challenging the notion of what ‘being Asian’ looks like in the first place. In this sense, one could even say that the paintings are more about ‘being American’ than ‘being Asian.’ Ultimately, I’m trying to formulate a more complicated and uncomfortable way of understanding identity.

In your paintings you depict surreal scenes involving bodies and animals, more specifically women and American bullies characterised by their seemingly equal relationship.

Significant otherness, which was coined by Donna Haraway in her book The Companion Species Manifesto in 2003, is that precise bond between the lives of dogs and people. Dogs are here to live with, not here just to think with. What made you want to explore that thematic?

The series draws from the book Animacies by Mel Chen, and from The Companionship Species Manifesto by Donna Haraway. Animacy in linguistics is the quality of sentience/liveliness/human-ness that a noun has, which then has grammatical and syntactic consequences. Mel Chen tugs the concept of animacy away from linguistics to argue that animacy is just as applicable in queer and race relations, one example being how ‘dehumanising insults hinge on the salient invocation of the nonhuman animal.’ The Chinese title of this painting ‘狗女人放狗屁’ translates literally to ‘dog woman releasing dog fart’, but it is actually a combination of two common insults, the first half meaning ‘bitch’ and the latter half meaning ‘bullshit.’ To tack on ‘dog’ in front of an animate ‘woman’ transforms it into an insult, just as tacking on ‘dog’ in front of an inanimate ‘fart’ also transforms it into an insult. In these cases, a very notion of a dog is dehumanising and degrading, revealing a human-centric metric of worthiness and value. In the painting, the woman and the dog take on the same stance (known in Western yoga practices as ‘downward dog’), but our desire to project a human understanding of gesture prescribes sexuality unto the former and playfulness unto the latter.

Bitch and Bull, 2021. Courtesy of the artist

In The Companionship Species Manifesto, Haraway makes a case for reevaluating our relationship with all our worldly co-habitants, dogs being a significant example of the intimacy and historical co-evolution that humans are capable of. However, the value of dogs’ lives do not and should not depend on their obedience to or intimacy with us, (i.e. if they are loved/accepted by us or if they make us feel loved). Marginalised communities have long been put down by being compared to animals (dogs, monkeys, general pre-homosapien ‘savages’), and thinking of ourselves as truly no better than dogs is the first step in working towards a non-anthropocentric post-human future.

You employ a specific use of colours in your artworks with a very appealing dramatic red and an unnatural neon green. Could you delve into your colour code and the connections it holds with your background?

Would there be another colour you would want to introduce more frequently? What would be the symbolism?

That series started because I wanted to practice using the colours red, and the colour green is the complementary colour on the colour wheel. But, because red and green often look festive and Christmas-y, I wanted to use the neon green to avoid that effect and create a more psychological atmosphere — if you put two complementary colours that have the same value right up against each other, the eye will create this vibrational effect that I find very effective.

Right now I’m trying to work in more drab colours — restraining your use of colour can be just as hard as amplifying it. I’d love to make a series of black paintings one day, like Goya.

The nude women you paint present such strength about them. There’s a mix of grotesque but also realistic elements. What is your idea of beauty?

My idea of beauty is self-assuredness, and that finding the thing that works for you is sexy.

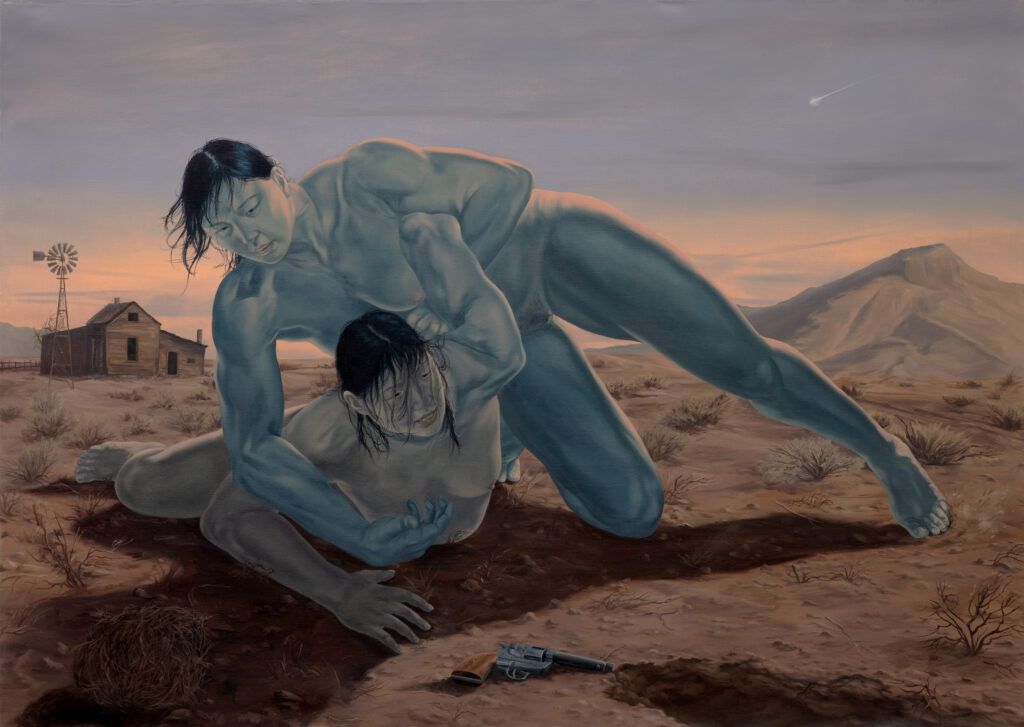

American Western, 2022. Courtesy of Gagosian

Would you say your artworks are self-portraits?

Yes and no. Painters always say that any painting of a person that is not of a specific other likeness (as in, a figure you make up vs. an image of a celebrity) is in some ways a self-portrait. Even a portrait of someone else can be a self-portrait in the sense that it portrays the artist’s relation to the sitter. But I don’t think of my paintings as self-portraits unless specified otherwise — I use my own face and body for reference, but I distort them to my liking. Maybe these characters are more like my kin.

What’s the process behind an artwork like usually? Do you sketch it before hand or do you just directly, sort of intuitively, paint? How is your research process like? How long does one painting take you and do you ever work on different paintings simultaneously? Do you prefer focus on one canvas?

At this point in my career, I’m mostly working towards shows, so first I think about what the overall theme of the upcoming show is, and how I want all the paintings to interact with one another and comment upon the theme. Then I read, watch films, go to galleries/museums and browse through images until I know what the content of the painting should be. Then I make several sketches until I’m satisfied with the composition and then I take my reference images. Once I’ve collected everything I need, that’s when I begin the painting. I usually focus on one image at once, but sometimes I start the under-paintings of two or three and leave the paintings that are harder to figure out to marinate at this stage, before going back to them months later.

The figures you paint almost seem like sculptures in their shapes and their volumes. Would that be a medium you would want to explore too? There is also a certain cinematography that envelops your paintings, almost stills from scenes. Would you explore film making too?

Yes, I have every intention of exploring sculpture/installation and film. I think it would be refreshing and surprising to gain literacy in a new medium — painting is so familiar and legible to me. That’s actually happening very soon, so stay tuned…

I watched an interview of yours published 4 years ago, in which you showed your paintings and shared how the atmosphere of those was similar to your dreams. I noticed a shift in composition and technique in comparison to now. Of course artists evolve constantly but I was curious to know if there was anything specific that had happened that instigated this new direction, almost allegorical?

I think what you’re picking up on is that my research process changed a lot, and that’s really affected the kinds of images I come up with. Perhaps before they relied more on personal experience, and now I’m trying to move things beyond just how I feel. The theory that I read helps me to connect what I’m feeling to larger events, and opens up avenues for research. For example, I’m currently working on a show that is Ohio-themed. Maybe 4 years ago, I would have just thought about experiences I had while in Ohio, but now, I’m thinking of my time growing up there as a gateway into Middle American life: white culture, the ideological and political consequences of a swing state and late-capitalist revival of post-industrial cities.

Dinnertime, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

You used to sell one-of-a-kind handmade and hand painted items and clothing before, and had gained quite a following on your Depop account. We have seen artists before collaborating with brands, for instance, American photographer and artist Andres Serrano with Supreme in 2017, Ghanaian painter Amoako Boafo with Kim Jones for Dior Spring Summer 2021 and Spanish artist Santiago Sierra for Balenciaga Spring Summer 2023. Would you ever envisage collaborating with a fashion brand? If so, which one and why?

I’d totally do that, but I wouldn’t want it to be like something I painted printed on a t-shirt. I’d love to go technical and make a bag or shoe collab, something structural and sculptural that takes a little more thought and work to design. I also thought the Prada x Elmgreen and Dragset collab was cool — that set of a Prada store out in the middle of nowhere, along a highway. That one defied the typical art x fashion collab (less like wearable art and more like an outdoor installation about fashion). I think the context of the collab really matters too, so it’s hard to pick a fashion brand without knowing the intended audience or the campaign. But maybe Margiela — Galliano’s own eponymous brand was already fusing art and fashion from the very beginning. Other than that, maybe something more democratic, like Uniqlo. I love Uniqlo.

Your first solo exhibition Homecoming was actually in Hefei, China at the Lai Shaoqi Art Museum. What was that homecoming like for you?

Homecoming was an exhibition, but it was also something of a performance. It became a literal homecoming — I was swarmed with local press, who were interested not so much in my artwork but in my backstory, which could easily be framed into something along the lines of ‘Chinese girl born in the USA loves her family and her homeland so dearly that she has returned to her homeland order to introduce her Western-educated art to her hometown!’ As I was making the works and news of the show began to spread, I could feel the increasing pressure and expectation of this sentiment. In the end, it was the desire to grasp what is likely the only opportunity for my grandparents to see an exhibition of mine that overrode the many forms of quiet tension I felt while producing this body of work.

You had your second solo show, The Incorrigible Giantess, last year at the PM/AM Gallery in London. Do you have any plans of showcasing your work this year, and if so, where?

I have a show in Columbus, Ohio coming up in September that I’m prepping for. Maybe that will be another homecoming of sorts.

Credits

Artworks · Courtesy of the artist, Gagosian, Gladstone and PM/AM