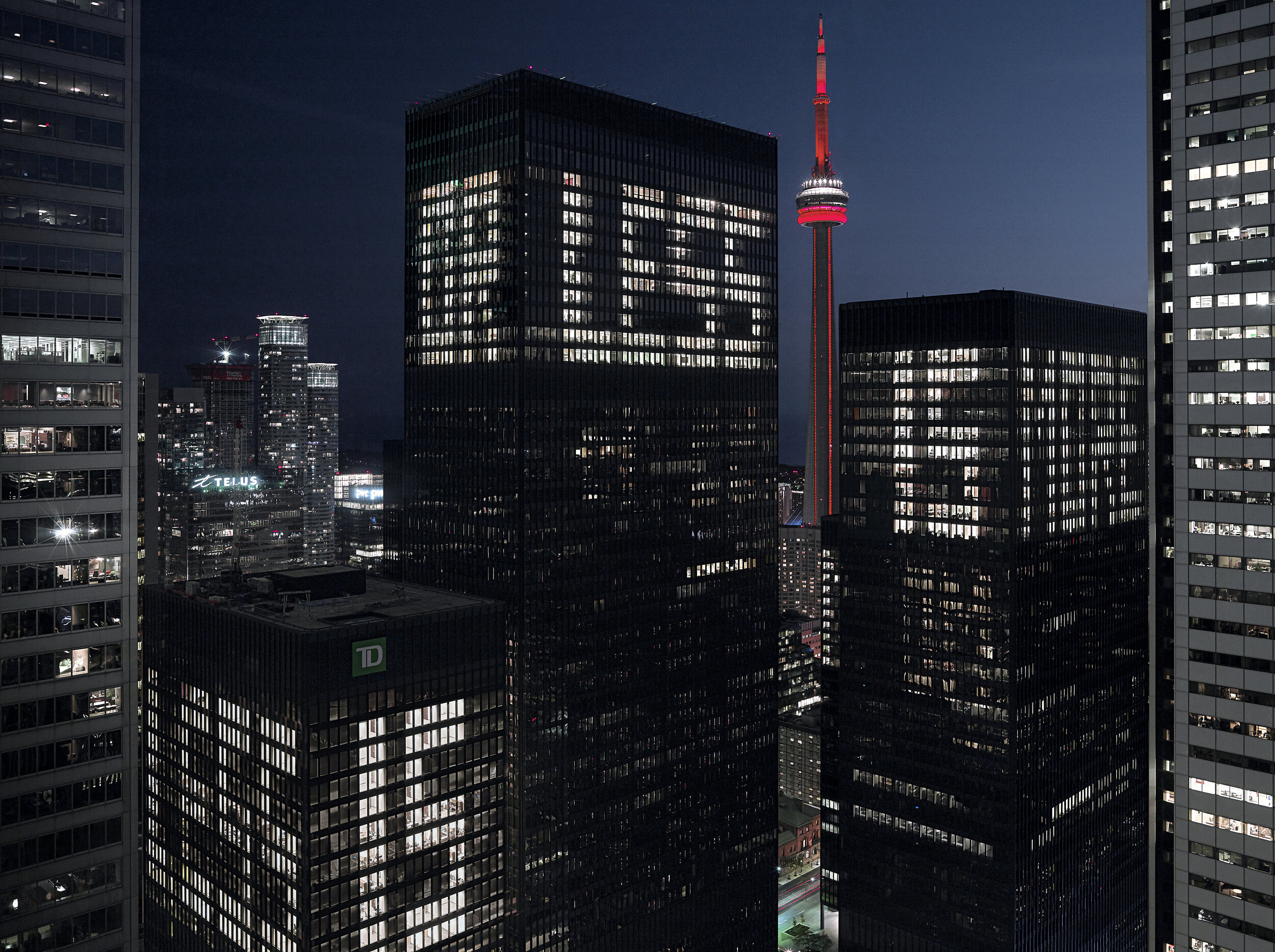

“to be hybrid is to be the future”

The art world, unfortunately, has a certain reputation for snobbery. Everything that is deemed as ‘art’ must, of course, be well thought out, aesthetically intriguing and completely unaffordable for anyone who isn’t part of ‘the rich’. Anything that is actually affordable for people who aren’t part of that income bracket is deemed as ‘low art’. Low art is defined as “for the masses, accessible and easily consumable.”

Over the years this definition has often been criticised alongside the common phrase “art for art’s sake” which was born from definitions like these and “is so culturally pervasive that many people accept it as the “correct” way to classify art.” Thus, it is rather surprising to see such definitions being alluded to in reviews of Noguchi’s exhibition at the Barbican as the artist himself was not a proponent of “art for art’s sake” according to Barbican curator Florence Ostende.

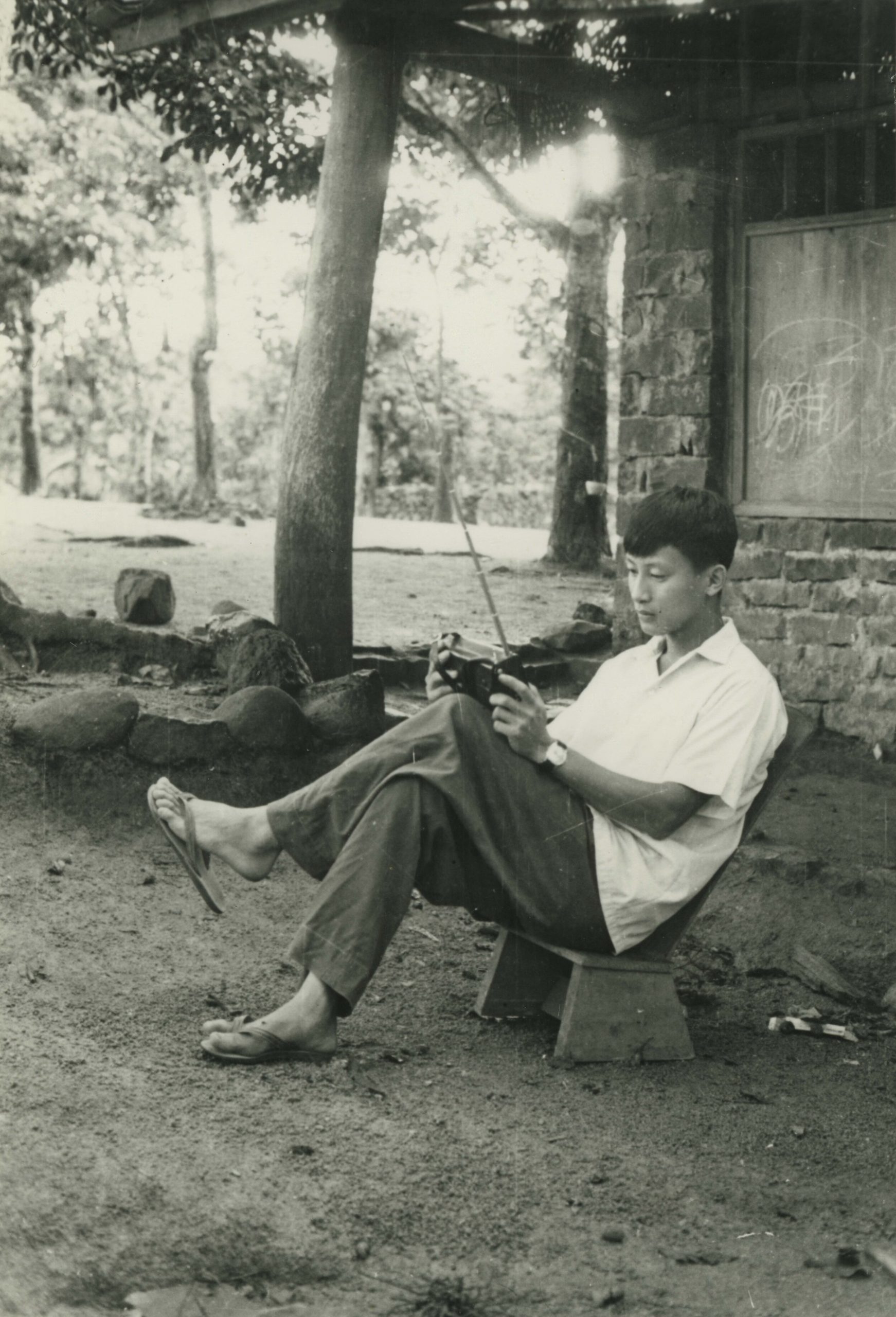

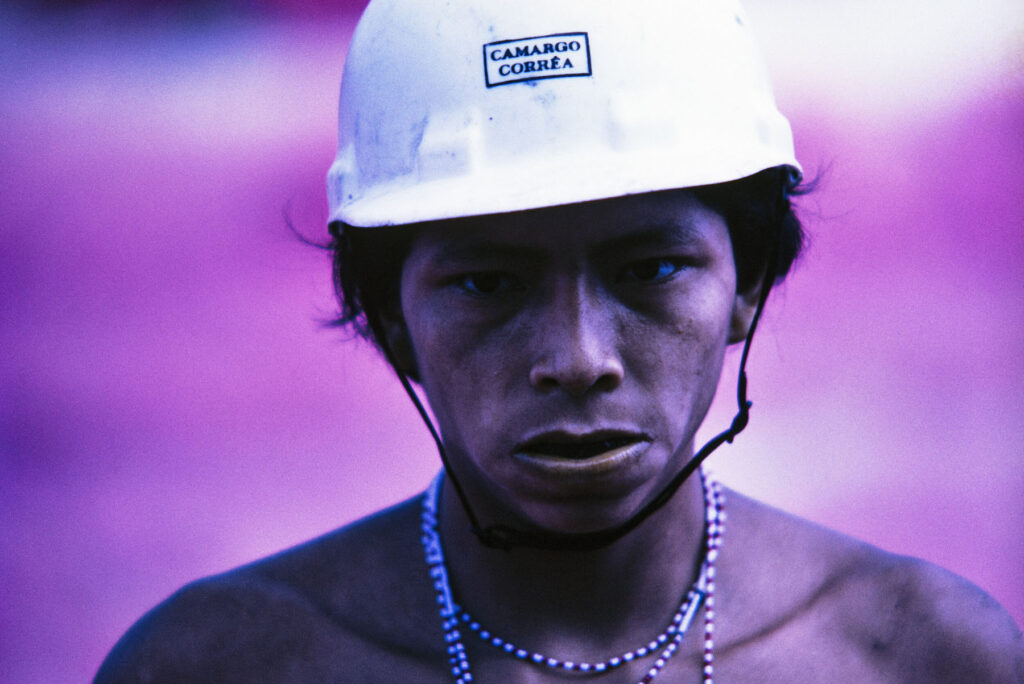

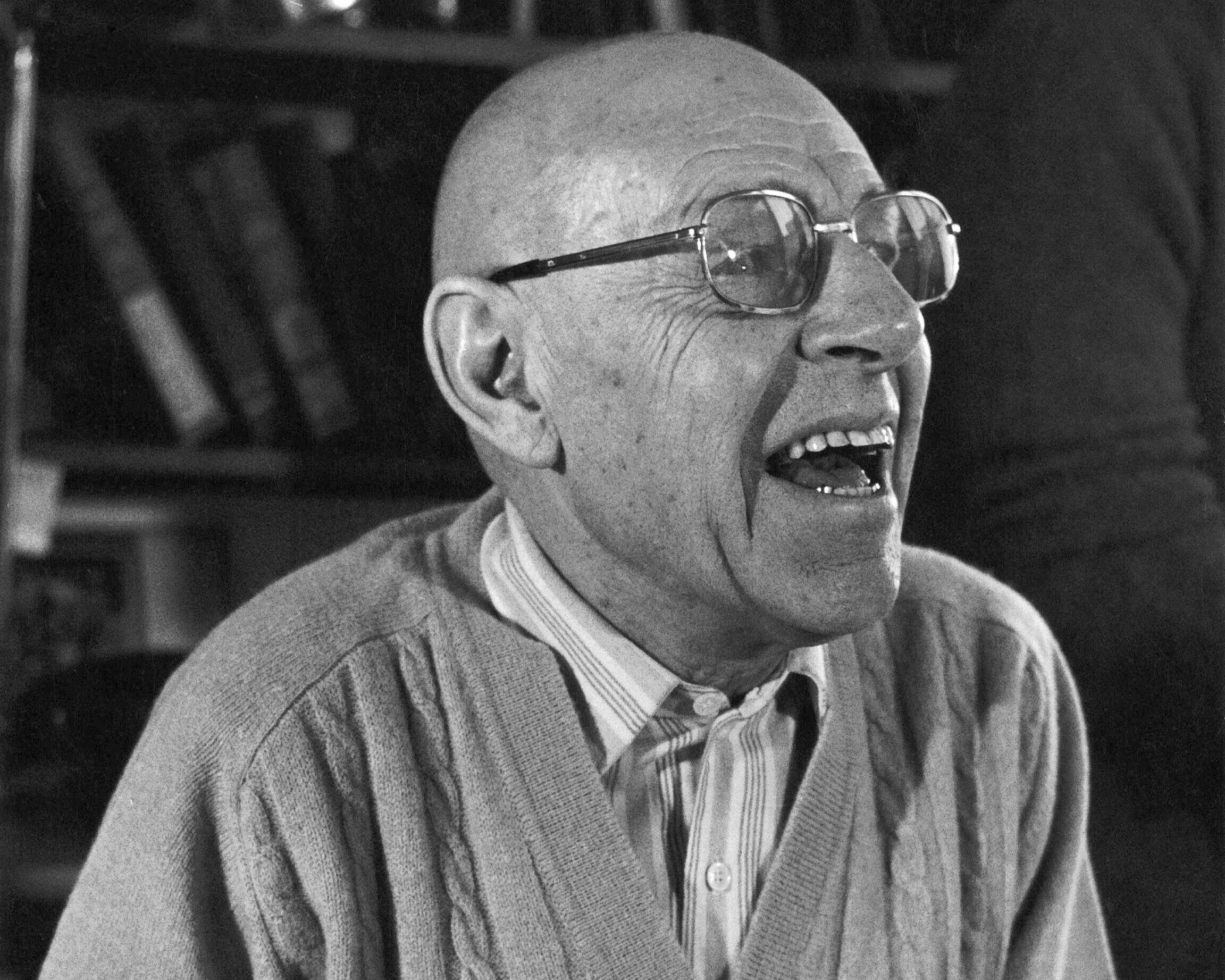

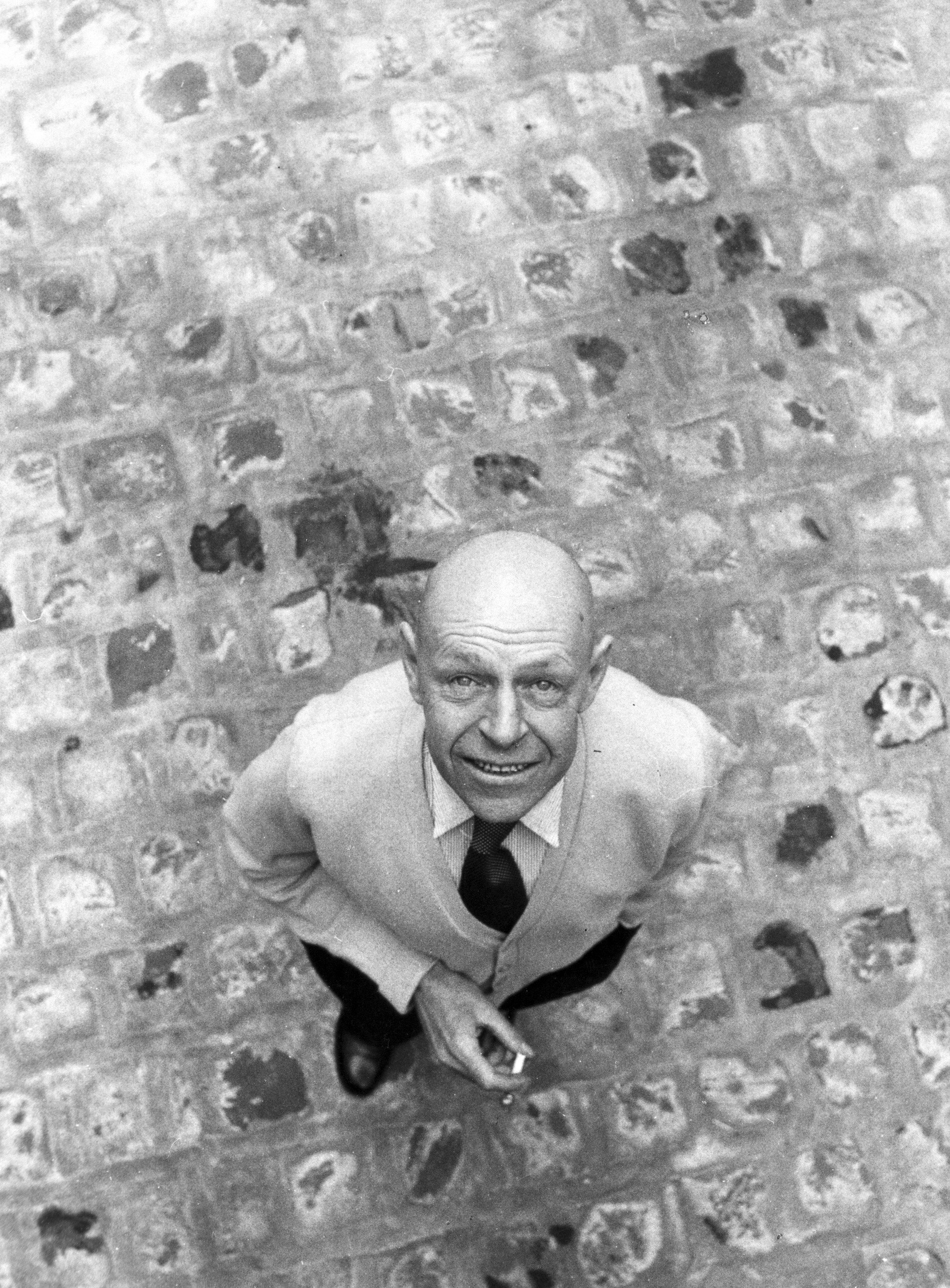

Japanese American designer and sculptor Isamu Noguchi was of “the most experimental and pioneering artists of the 20th century”. His exhibition at the Barbican displays over a hundred and fifty works from his career which spans over six decades and explores his life, work and creative method. The best way to describe him is a ‘creative polymath’ as his work straddled a multitude of disciplines.

The exhibition itself is on two levels and upon entering the space you are directed upstairs. This first section is divided into spacious alcoves and display different periods of the artists work. There is a slight feeling of disconnect here and one finds oneself peering over the railing to the floor below, which appears from above far more engaging. However, this part of the exhibition provides an important overview for those who are not so familiar with Noguchi’s work. It maps the artist’s collaborations with the likes of Brâncuși, Martha Graham and R. Buckminster Fuller, in addition to charting Noguchi’s activist work, protesting racist lynchings, America’s internment of its Japanese American citizens during World War II, and fascism.

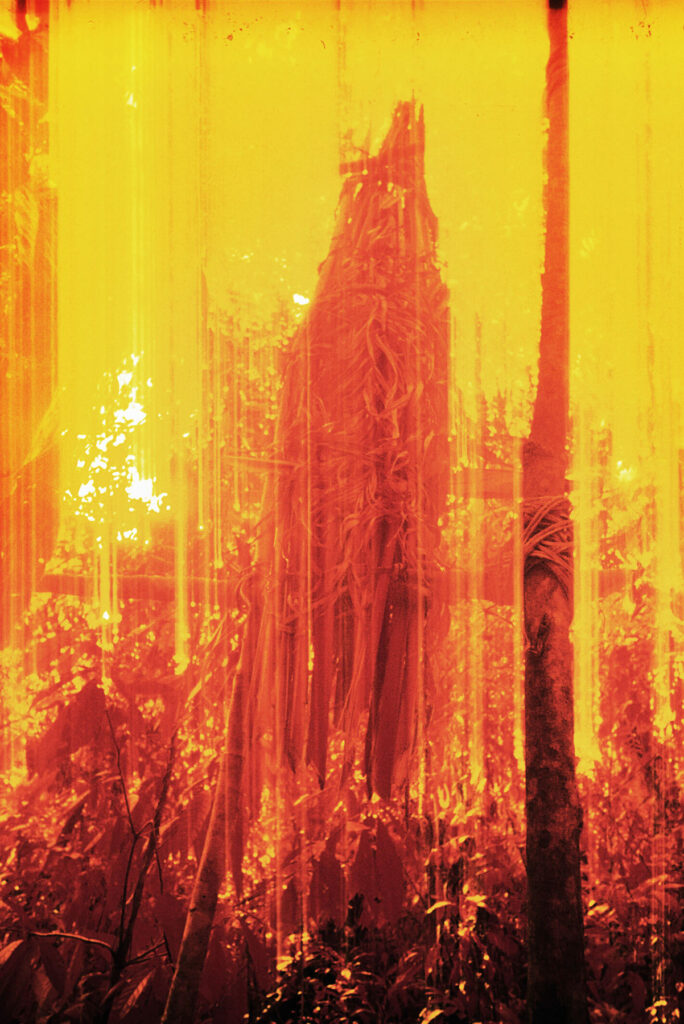

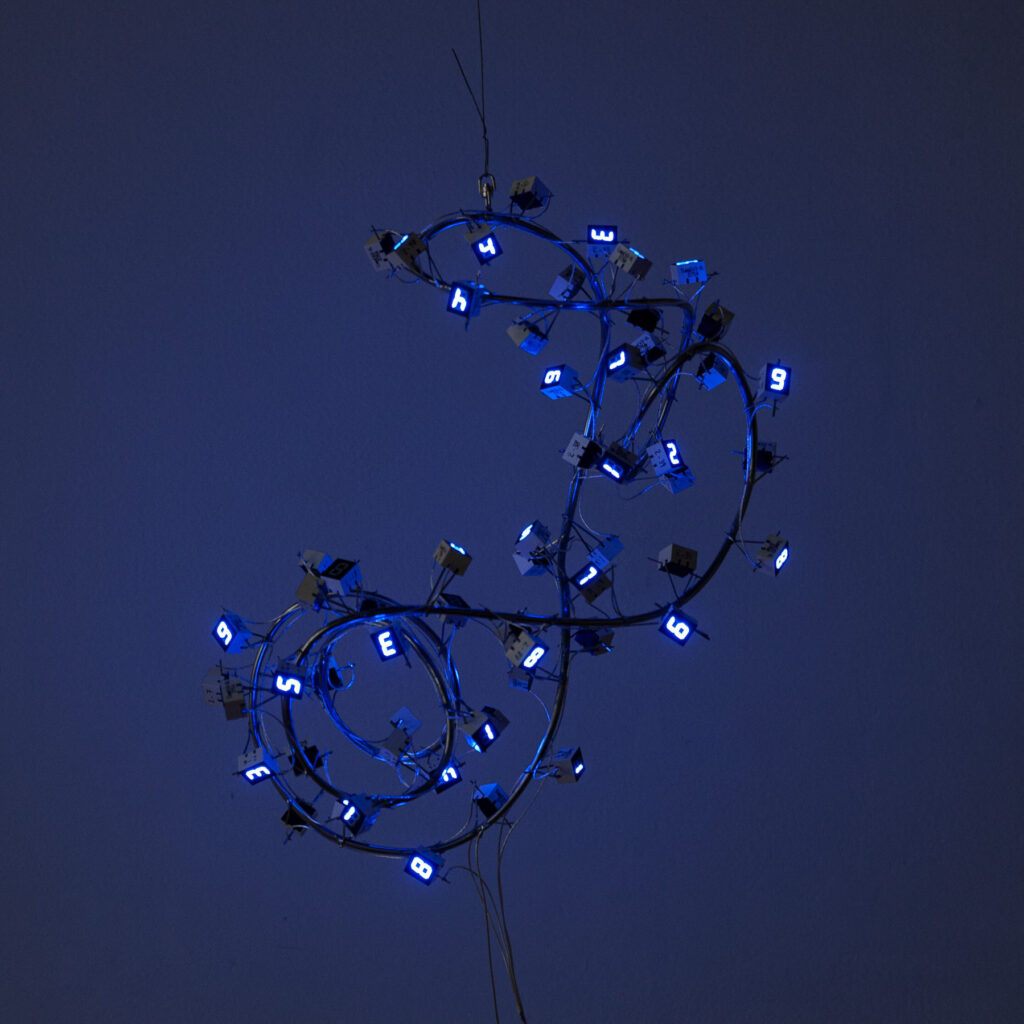

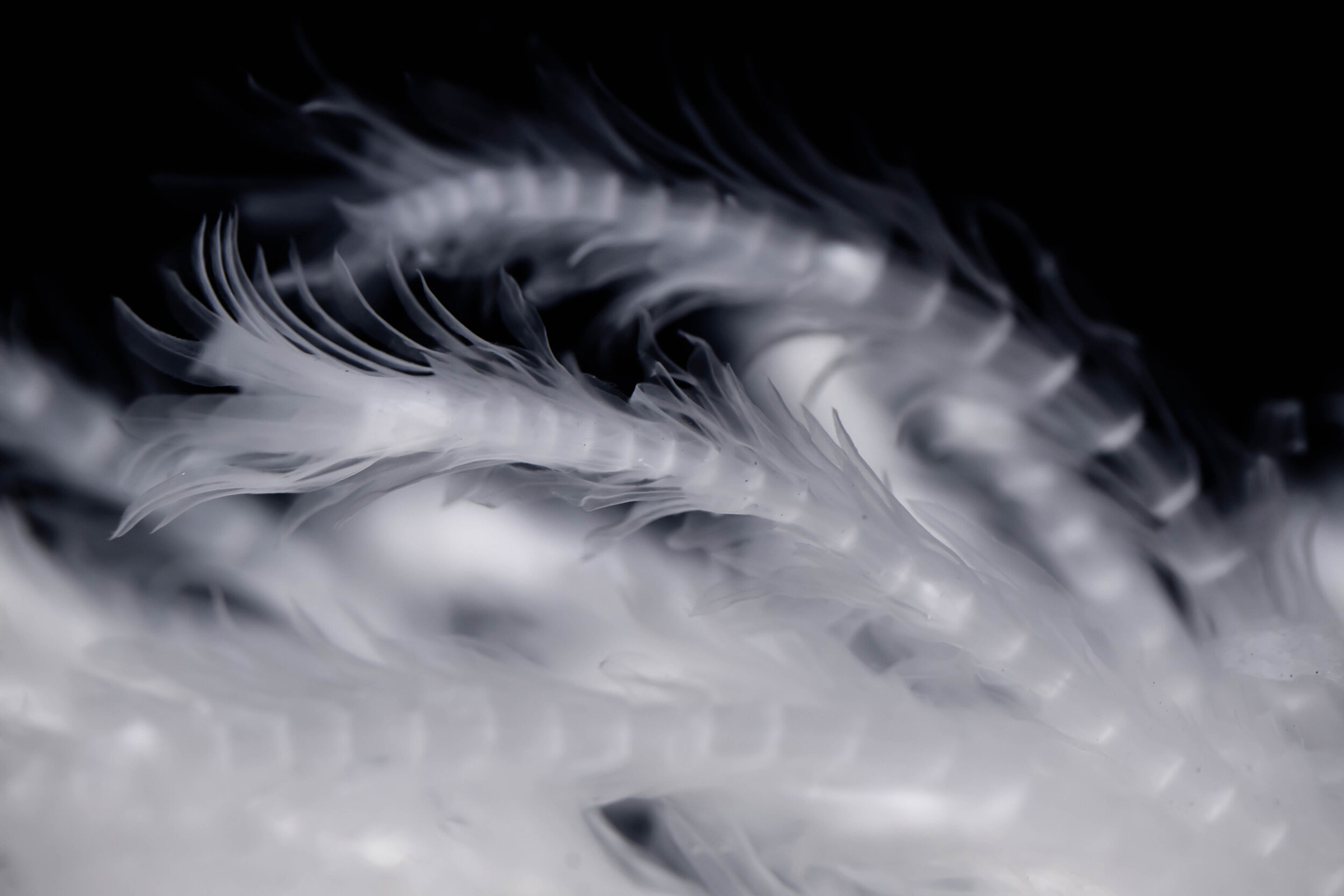

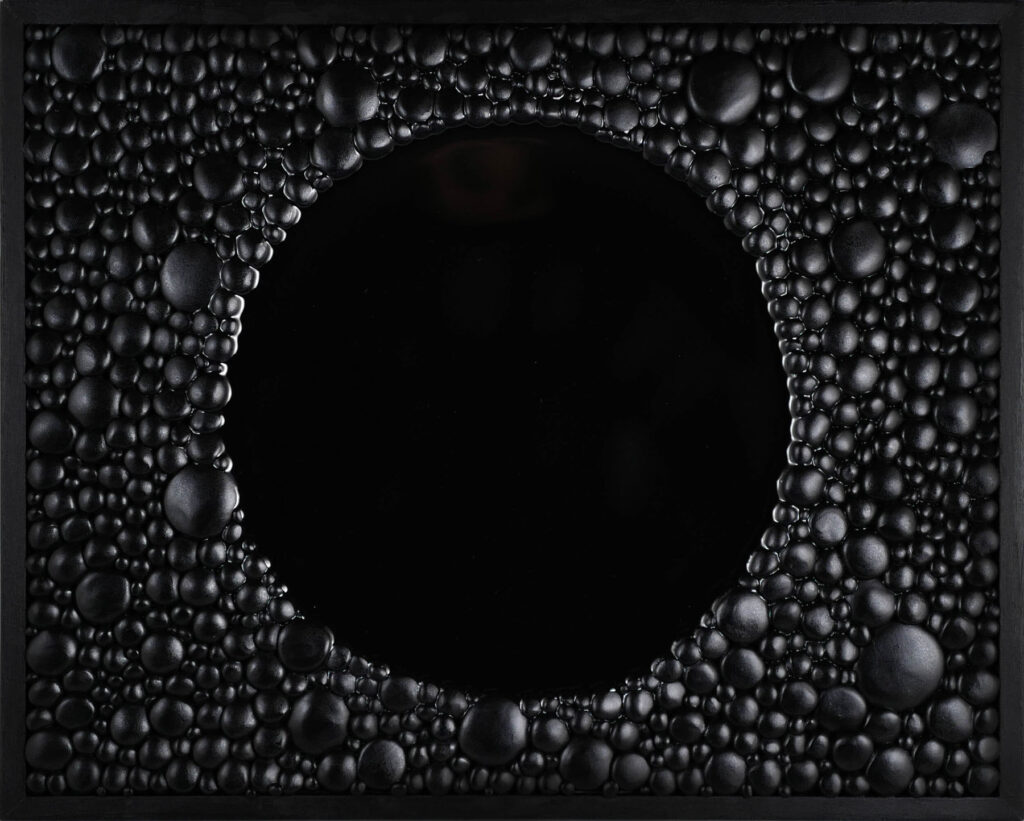

However, it is on the first level that the exhibition becomes a real delight, a rambling hodgepodge of stone and metal sculptures and his world-famous Akari lamps that makes one itch to play amongst this minimalist wonderland. Noguchi was committed to creating accessible public art and playgrounds, or playscapes, were a fascination for him. He designed these playgrounds as a way to “encourage creative interaction as a way of learning.” Indeed this interest in play and playfulness is echoed in the exhibition’s main space.

The star of the show is certainly the Akira lamps handing like softly glowing space ships, seemingly emerging from the floor like some strange luminous creature and arranged in clumps like brightly coloured mushrooms. Noguchi designed them after visiting struggling post-war Japan as a way to revitalise the economy. He took the Japanese bamboo and rice paper lanterns and modernised them as a way to bring industry back to the war-torn country.

These lamps became popular in Britain in the sixties and are still available, albeit in a slightly changed form, in IKEA. Because of this they are instantly recognisable and have led to some likening the Barbican exhibition to a ‘high-end lighting showroom.’ However, this brings us back to the discussion of ‘art for art’s sake.’ As I wandered around the exhibition I was drawn back to childhood memories of visiting B&Q with my parents, (they were the only shop in my hometown that had escalators and thus was an infinitely entertaining playground). Playground is the keyword here, I was allowed to roam the aisle alone in delicious freedom and explore this wonderland of light, metal, wood and a multitude of other textures, shapes and materials. To my childlike understanding, all of this was art. Interestingly Noguchi’s philosophy was rather similar. In creating the Akari lamps he aimed to “bring sculpture to everyday households”.

In our current environment of late-stage capitalism, Noguchi’s quiet and thoughtful philosophy’s on purpose, sustainability and environment are perhaps exactly what the art world needs. He saw commercial forms of design “as a way of escaping the art market and working with more freedom and fewer constraints.” While we might criticise the society we live in unfortunately we must still exist within it, however Noguchi “believed in the idea that even in mass-production, individuality is still possible.” We must adapt and innovate within the framework we have because after all, to quote the artist, “to be hybrid is to be the future.”

Credits

Images · Isamu Noguchi

Noguchi at the Barbican is open from Thu 30 Sep 2021 —Sun 9 Jan 2022. For more information visit https://www.barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2021/event/noguchi

Photos

- Portrait of Isamu Noguchi, American sculptor, the latter’s special assistant planner, July 4, 1947 in New York City. (Photo by Arnold Newman Properties/Getty Images)

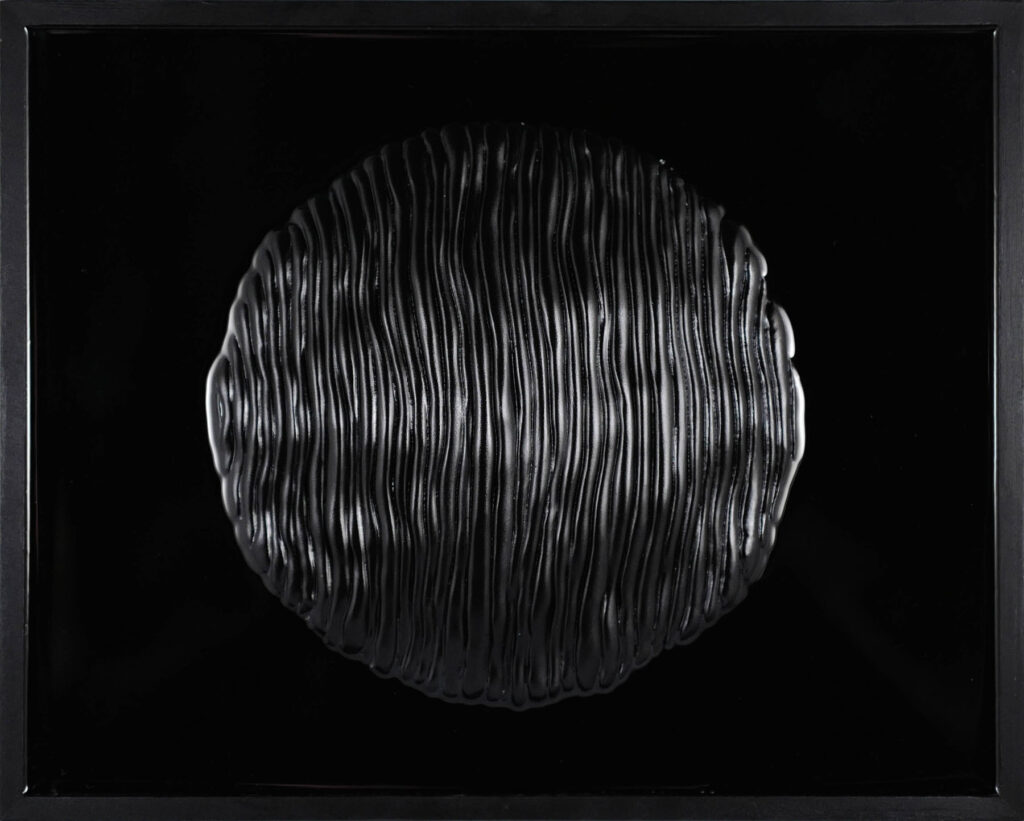

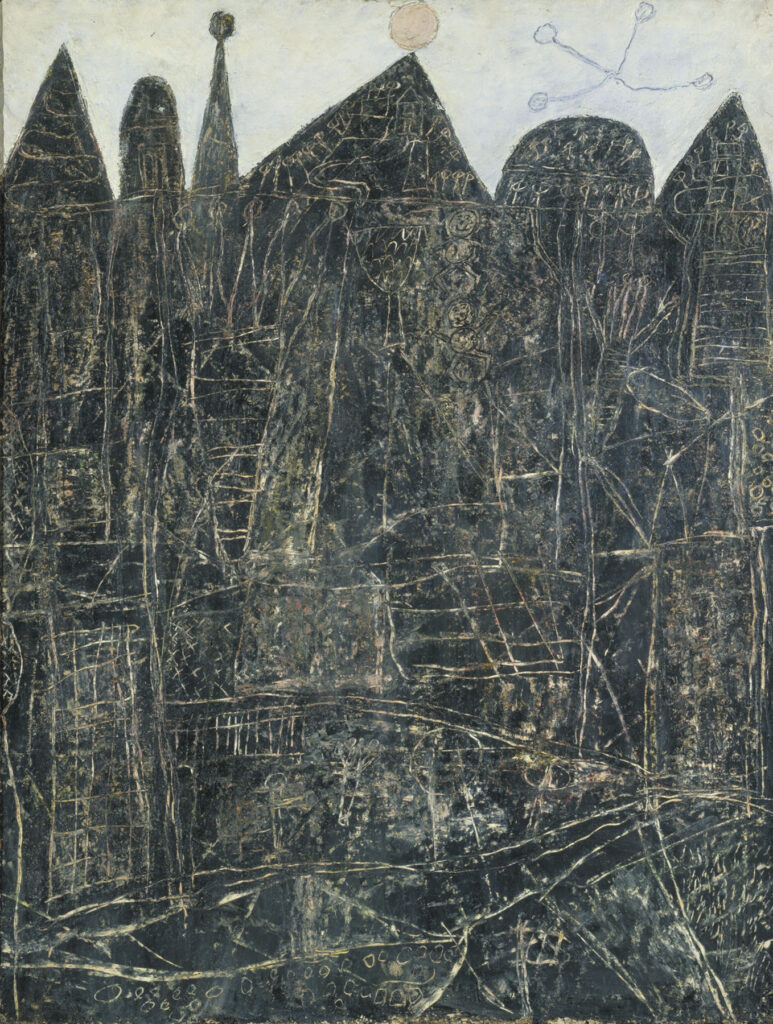

- Bronze plate

- Noguchi, Isamu (1904-1988): Humpty Dumpty. 1946. Ribbon slate. Overall: 59 ◊ 20 3\4 ◊ 17 1\2in. (149.9 ◊ 52.7 ◊ 44.5 cm). Purchase. Inv. N.: 47.7a-e New York Whitney Museum of American Art *** Permission for usage must be provided in writing from Scala.

- Terracotta and plaster