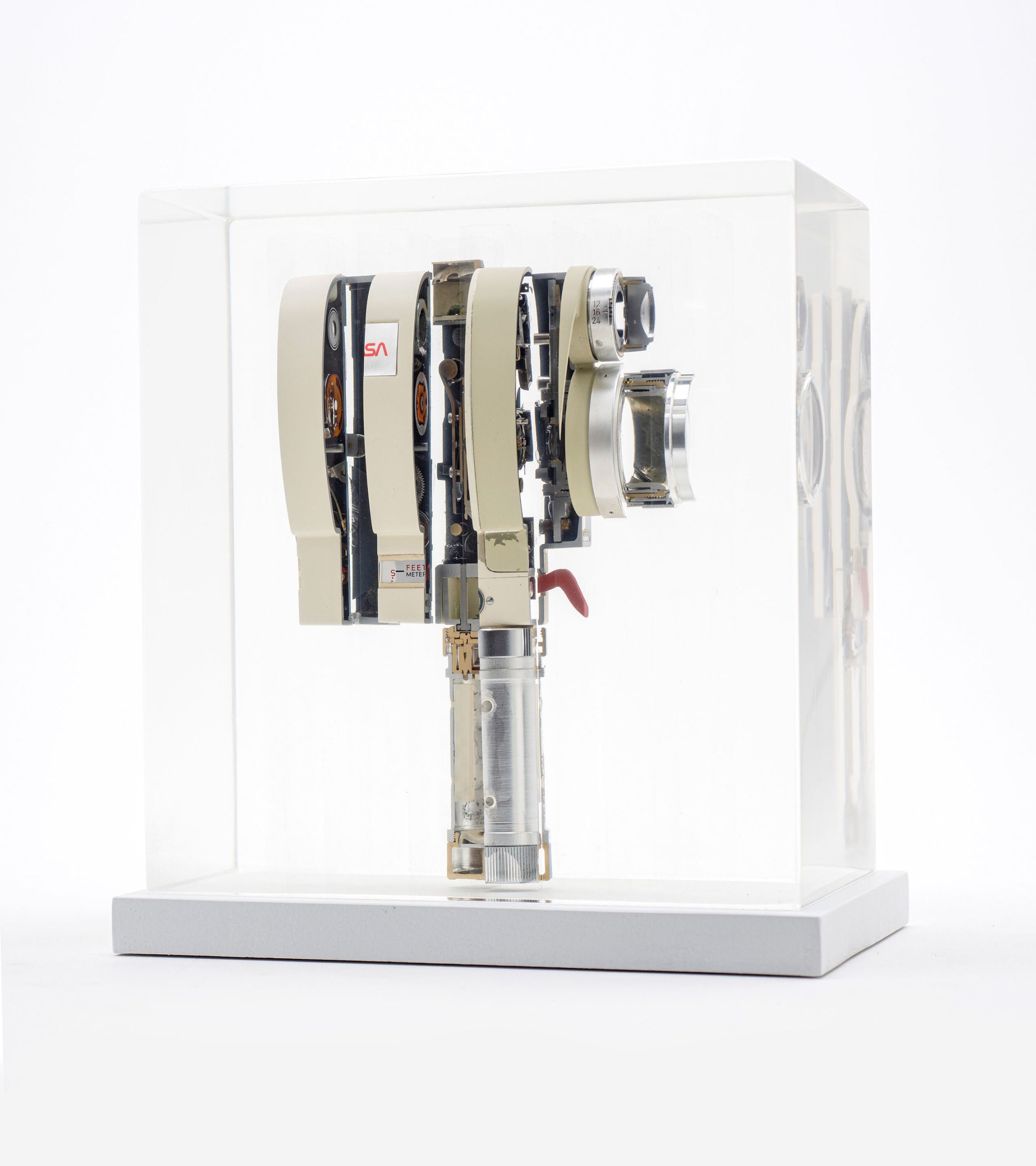

Rebecca Ackroyd, Hunter/Gatherer vii, 2018

From fragmented memories to ordinary encounters: Locating the subconscious in the work of Rebecca Ackroyd

Rebecca Ackroyd, 27, 2017

I speak to Rebecca Ackroyd via Zoom from her studio in Berlin in late August, not long before her solo exhibition, Fertile Ground, opens at Peres Projects in Seoul (until 13th October). She will also be exhibiting at this year’s Frieze London and in December at Art Basel Miami Beach. Fertile Ground, like much of Ackroyd’s practice, delves into the surreal whilst being grounded in the monotony of the everyday. In playing alone, for example, a cast of the artist’s hands in a sink is at once familiar and strange; the hands are disconnected from the body, whilst a blade – bloodied? – lies conspicuously in the basin. Those familiar with Ackroyd will know that epoxy resin casts of the body, often in lurid, sometimes grotesque colours, are a central part of her work. And oftentimes, fragments of these casts reappear in different bodies of work. In the Seoul exhibition’s title piece, fertile ground, the artist casts her arms, upper torso and legs wearing a pair of boots that belonged to her mother in the 1960s. The physical fragmentation of the artist’s body in this piece unpick the complexities of time and memory in relation to family history and connection. This can be evidenced by the fact that, as she tells me during our conversation, she has previously cast her mum’s ageing hands as well as her own, ‘and then in 30 years’ time, [mine] will be old and possibly look like my mum’s.’ This, she says, stems from an interest in preservation. But fertile ground also recalls, or reimagines even, an earlier sculpture, Tonguing the fence from her 2021 show,100mph which also features those 1960s boots. The 100pmh exhibition, which as the artist explains below came out of a dream journal she made during the first lockdown in 2020, had a crimson-tinged sleaziness to it. And if Fertile Ground grapples with the subconscious in order to examine how our sense of self is produced and reproduced through the memories we think we recall and stories we tell ourselves, 100mph delved into a very different part of the psyche. There, the works – and in particular Ackroyd’s gouache and pastel pieces – seemed to unlock a Pandora’s Box of what the artist terms ‘bad thoughts’. In pieces like 1,000,000 Eggs, green flesh gleams through fishnet tights, the strangeness of the tinted skin offset by a blood-red hand rested slightly coquettishly on a hip.

In unison with other pastel works on show at the exhibition,100mph recalls the garishness of Otto Dix’s triptych of Berlin nightlife from the early 1920s; in Metropolis (1925), like Ackroyd’s pastel works, there’s an uneasiness that oozes out – as a collective uncertainty seems to seep through the polished cracks (or, in Ackroyd’s case, grazed knees). Even the most exciting of circumstances – for Dix, a bustling club playing jazz music, or for Ackroyd, the experience of catching a flight to go on holiday as her work Singed Lids from the 2019 Lyon Biennale depicts – can be boring experiences. Resin casts of airplane seats are positioned in the artist’s character disjointed fashion, with the remnant of a leg or a suitcase making the odd appearance. In that work, Ackroyd again recalls a collective encounter, pieced together through the fragmented lens of a distant memory. Of course, the comparisons with Dix are limited – he was attempting to capture a broken society in the aftermath of war and hyperinflation, and the sexual politics are a far cry from Ackroyd’s own handling of sexuality and femininity. But nonetheless, both seem to touch on how we, guided by that inner voice in our head, collectively go about trying to make sense of the world around us. And below, as the artist discusses the importance of ordinariness in her work, it seems that sometimes the most ordinary of circumstances feature in the strangest of dreams.

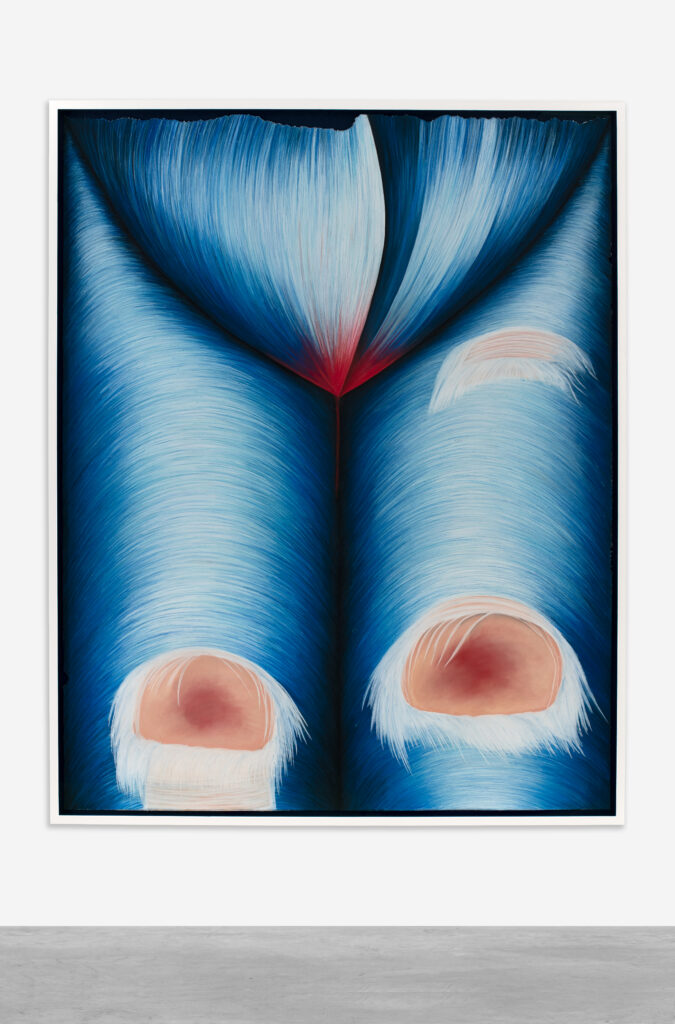

Rebecca Ackroyd,

Flower form, 2022

Rebecca Ackroyd, Flower form 2, 2022

Something that strikes me about your work, and seeing how it’s installed in exhibition spaces, is the idea of the encounter – and encountering the work in a space. For example, you’ve previously spoken about the use of a pub carpet as a recurring motif since you first used it in previous exhibitions in 2017, which is both part of the exhibition install and the work in a way. How do you think about the work within the space, and how do you visualize the experience and the encounter that the audience will have with your work in situ?

It really depends on the show and the mood at the time that I’m making the show. The last show I did at Peres Projects Gallery in Berlin, 100mph (2021), took place during lockdown and the basis for the work started from a dream journal I was making in the first lockdown. The works didn’t directly correlate to the journal though I ended up showing drawings from the dream journal in the show on a separate table. [But] it was mainly drawing because I didn’t have any assistance to make sculpture, and I was just working on my own with my boyfriend (he was my assistant!)

The work was really informed by the idea of dreams, psychological space and something that’s more of a subconscious thought that is buried or hidden.

Rebecca Ackroyd, RAY!, 2018

“There was very much this relationship between a sort of deep internal space and bringing that out. I was really interested in how that could kind of be expressed through sexual desire or ‘bad thoughts’; a sort of internal mechanism of thinking that we don’t express.”

That was the driving force behind a lot of the drawings.

The way install or approach altering the space really depends on the show, the content and the way I want it to feel. But I am definitely interested in there being familiar elements, like a carpet – the pub carpet, that I’ve used repeatedly, and I used again in 100mph – as a way of signifying a time, or a place, or a culture, and then contrasting that with these out-there drawings or psychological abstract works. I’m really interested in bouncing between places, and I think that’s definitely reflected in how I assemble a show.

Rebecca Ackroyd, Hear Her, man hole, 2018

For your most recent show, Fertile Ground (2022), reference is made to an encounter you had with a building site in London. But to what extent do you look for an influence or an inspiration when it comes to making a body of work, or does a body of work come out of something more instinctive?

I think it really depends, like with Fertile Ground, you mention the building site – I wouldn’t say that that memory necessarily meant, or influenced, the actual works themselves. I think I’d started making the work already, and it’s almost like I look for anchors that root the work in different ideas.

Rebecca Ackroyd, 1990’s REST, 2018

And that particular memory felt like it grounded the show somehow. In fact, I wanted the building site to be the show image, but then I found the photo of it, and it was such a boring photo. I thought the idea was more interesting than the reality. In my head, I’d built it up as this really overwhelming visual encounter – which I think it was, but it just didn’t translate into an image at all. It just looked like a building site.

“It’s more interesting when the work is layered and bounces between different ideas of abstraction, figuration, personal history, and then more shared ideas of existence or life – or something more ubiquitous, like a shop shutter, or a tool.”

I’m interested in how work can be layered in that way basically; layering content and layering ideas.

Rebecca Ackroyd, Tide Turn 2018 UK, 2018

In Fertile Ground, you’ve got the cast of yourself and you’re wearing your mum’s boots from the ‘60s, which is a very personal connection to your own experience. But, from what you just said, I get the impression that your work is less autobiographical, and the use of personal history is more a vehicle for exploring certain themes at a particular point in time?

Yeah, definitely.I mean it’s difficult, isn’t it? I think the term ‘autobiography’ sounds very literal, and so Idon’t necessarily see it as autobiographical. I see it more as ‘biographical’, in the way that I’m really interested in stories and memory, and how that becomes so fragmented. That informs so much of who we are. With the memory of the building site, I had this vision of something, and then when I actually looked at it, it was really underwhelming! And so, sometimes the thought of something is much more exciting, or inspiring than the reality of it.

Rebecca Ackroyd, RA MULCH, 2018

That also correlates with the creative process for me. I was talking about this to a friend recently, another artist (Sam Windett)– we were saying how when you’re making a show, you’ve got the idea of the show in your head and you’re really driven towards it. And then, you have the reality of being confronted with what you’ve actually done in the space.You’re suddenly in reality and you have to just deal with the fact that you’ve made these works. And that’s what it is – I feel like there’s always a tussle between the idea of the thing, and then the thing itself.

That’s really interesting because the underwhelming reality of the building site memory also ties into the idea of the mundane that features in your work. In memories and dreams, we pick up on small things and remember them, but the reality is definitely not going to be what you thought it was. In works like Singed Lids (2019), for example, there are these bits of everyday detritus – the suitcase by the side of the seat. Is that mundane, or a way to be able to visualise through small fragments the things we can’t fully recall?

I think it’s both. In Fertile Ground, there’s a cast of a sink with my hands. I’m really interested in ordinariness, especially with the sculptures. I like the idea of just capturing something that is quite unspectacular, you know – like doing the dishes. I’m more interested in that than I am a performative gesture or something. It took me quite a long time to realise that there’s something really special about living with ordinariness; appreciating normal, day-to-day experiences.

Rebecca Ackroyd, Carpet burn, 2022

And then the fragmentation within the casting is very much about referencing something incomplete, which again links back to the idea of a memory, or, with the Singed Lids piece, a remnant of something. Casting is a very direct way of being able to do that, and I see it as being related to photography in terms of capturing a particular moment.

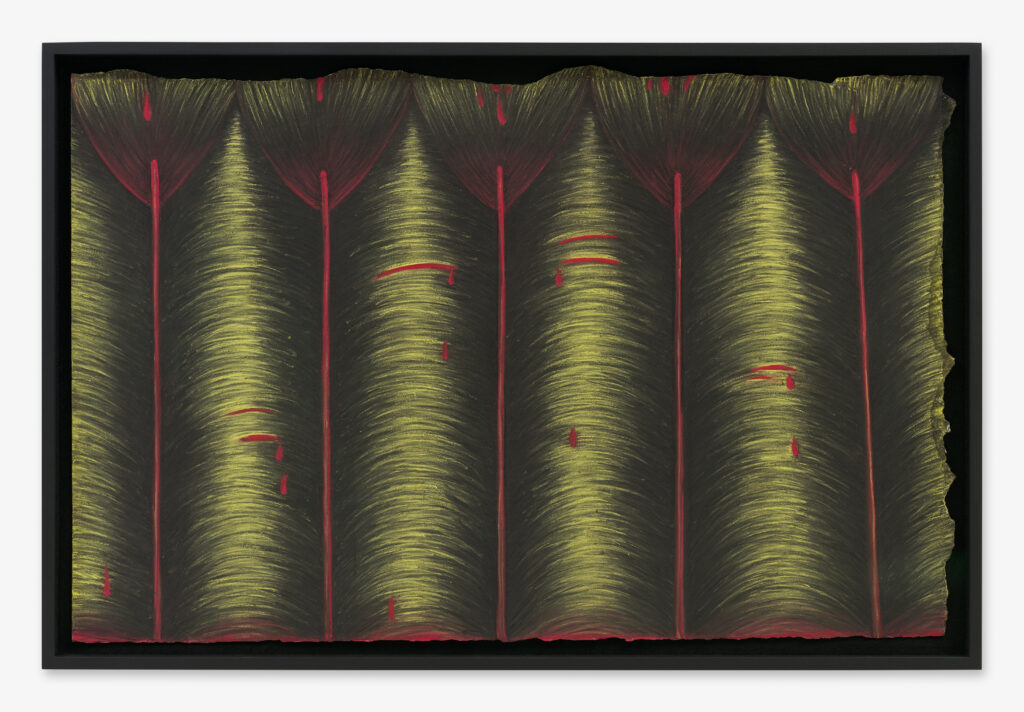

Rebecca Ackroyd, 100mph, 2020

Rebecca Ackroyd, 100mph, 2020

I think that’s really interesting because it’s almost like a reliable, true record of something. Whereas, with other mediums such as drawing, that’s always going to be more of an interpretation. And so, I wanted to ask you about the process of making work, and the contrast between having these sculptural works using materials like resin and wire, versus pastels, for example. How do you balance using these different approaches of making, and how do they then work together to create a wider body of work?

I came from making only sculpture to making these small drawings between bodies of work. And then, gradually, the drawings became the pastels, and now they’re as important. I don’t really see a distinction between the processes now.

Rebecca Ackroyd, Hunter/Gatherer viii, 2018

But with sculpture, the thing I struggle with is how full on it is physically. It’s something I have to plan a lot more and think about more in terms of practicality and how things are going to work.But quite often, when I make a cast, we make them in pieces in the studio, and then they’ll just kind of sit around the studio for months. Then eventually, they get incorporated into a work.

“So, in a weird way, my studio is a bit like a sort of graveyard! And then, they get brought to life.”

Rebecca Ackroyd, World view, 2020

I use the drawing and the sculpture in different ways. With the casting, it’s about bringing an element of reality into the work – using myself or a friend or family member, and then grounding that in a particular moment.

With the drawing, there’s definitely a greater freedom in terms of making, which is why I started them. I pretty much make every single one in a small version before I make them big, so I can work on a lot at the same time. I often have numerous ideas that I want to get out, then I can look at them and it gets translated onto a bigger scale. Or they just stay small, or I never show them.

“Making work is about finding ways in which I can have as much freedom as possible.”

It’s really important not to be precious, because once the drawings are on a bigger scale, there’s more pressure there to make it work. I think it’s really important to have the freedom to fail all the time. And I feel like with sculpture, it is this battle to not fail because it’s much harder to articulate. It’s a very different approach, but I feel like in a lot of ways, they inform each other.

Rebecca Ackroyd, Half moon or empty, 2020

You mentioned that you might cast something and then use it at a later date in a body of work. Do you see different bodies of work as a progression, or as a response to a previous body of work?

I think it really depends. With the sink piece in Fertile Ground, I never thought I would show it because it was just on the floor of my studio for years and then it just seemed to make sense suddenly. So then it gets used in a completely different context.I think it’s probably a bit of both because, when I’m conceiving a show, and especially when it’s in a particular space that I’ve been to, I will be mulling it over and figuring out what I want it to be. I’ll imagine how I will enter that space and then that will inform certain elements – like what I might do to that space. But in terms of the individual works, I think quite often I just have an idea for work, and then I’ll make that piece. But sometimes, it’s less formed than that; it’ll just be a fragment of something, and maybe I’ll make a metal stand for it.

Rebecca Ackroyd, Tonguing the fence, 2020

It really snowballs when I’m making work for a show. I’m not a very good planner; I think that’s just the way I work, though. I have to be able to change and shift things.But then it’s funny, because earlier today, I was thinking of a show that I don’t even have planned, it’s just an idea for a show of work.

“I like to have that openness, and I also like to not necessarily know exactly what a show might be because it’s much more interesting and exciting, and it means that the work can turn into something unexpected.”

With Singed Lids, I don’t think any of the curators even knew what I was doing because it was just like, “here’s a cast of an airplane seat”, or “here’s this cast of a leg”. You couldn’t see the whole thing. I didn’t even see the whole thing until I was in the space; I had no idea if it was going to work or be any good. It’s quite terrifying to do that to yourself, but I do think that that can be one of the best ways to work, it allows the work to unfold.