“Every time I forget my camera, I have regretted it. Life isn’t worth living if I can’t take a photo of it.”

A respected cult figure in skateboarding culture, Ed Templeton’s photography takes inspiration from the subculture he is a part of and its suburban roots. Born in Orange County, a sprawling suburb of Los Angeles, the world champion professional skateboarder and founder of the iconic skate company Toy Machine has exhibited his work across Los Angeles, San Francisco, Paris, Belgium, Vienna, the UK and more. His work is also housed in LACMA’s permanent collection, and he has published over 20 books of his work.

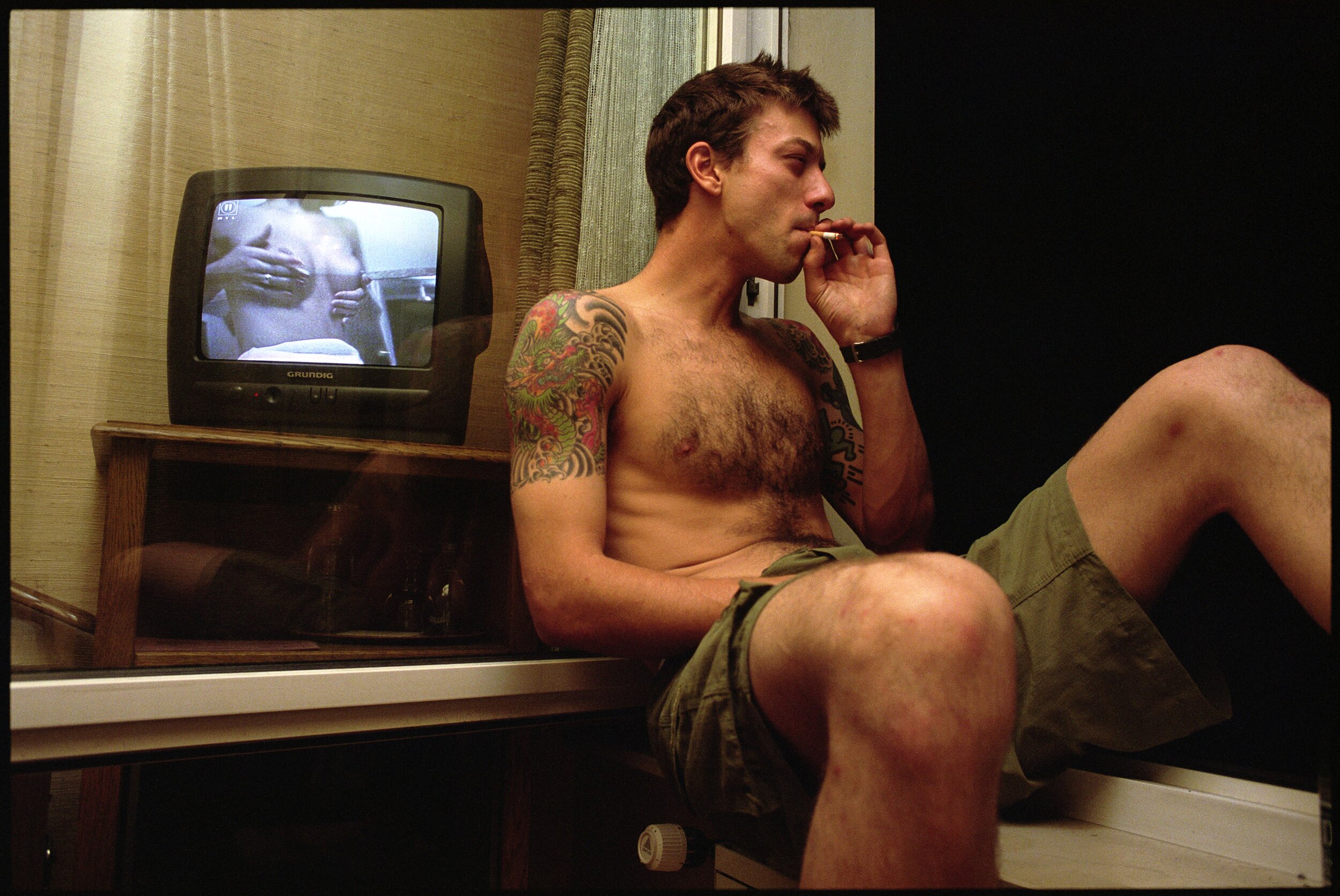

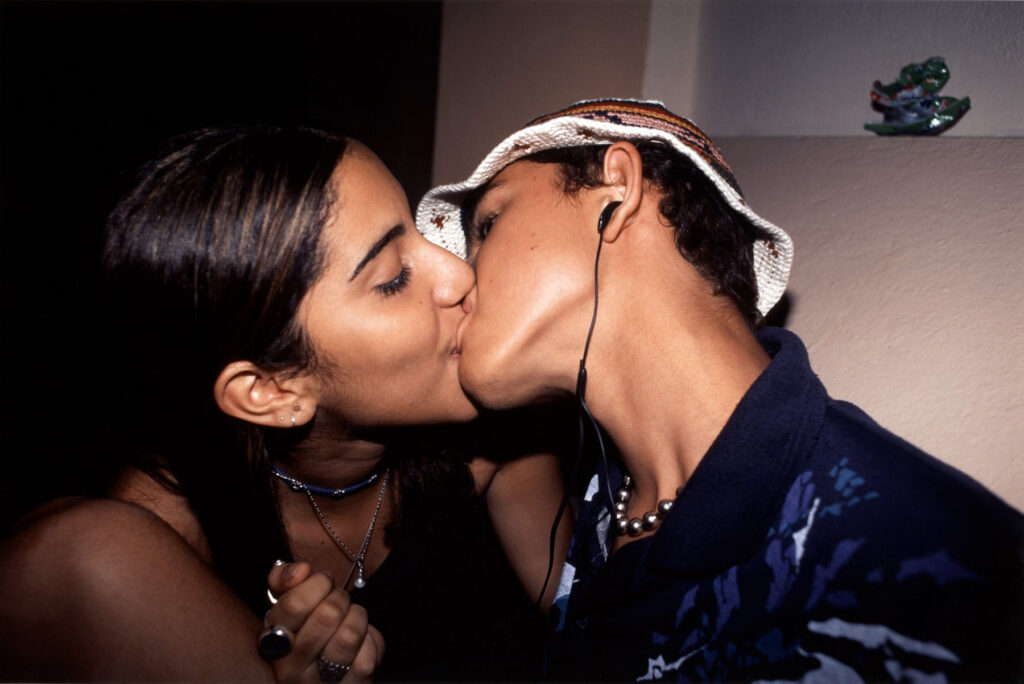

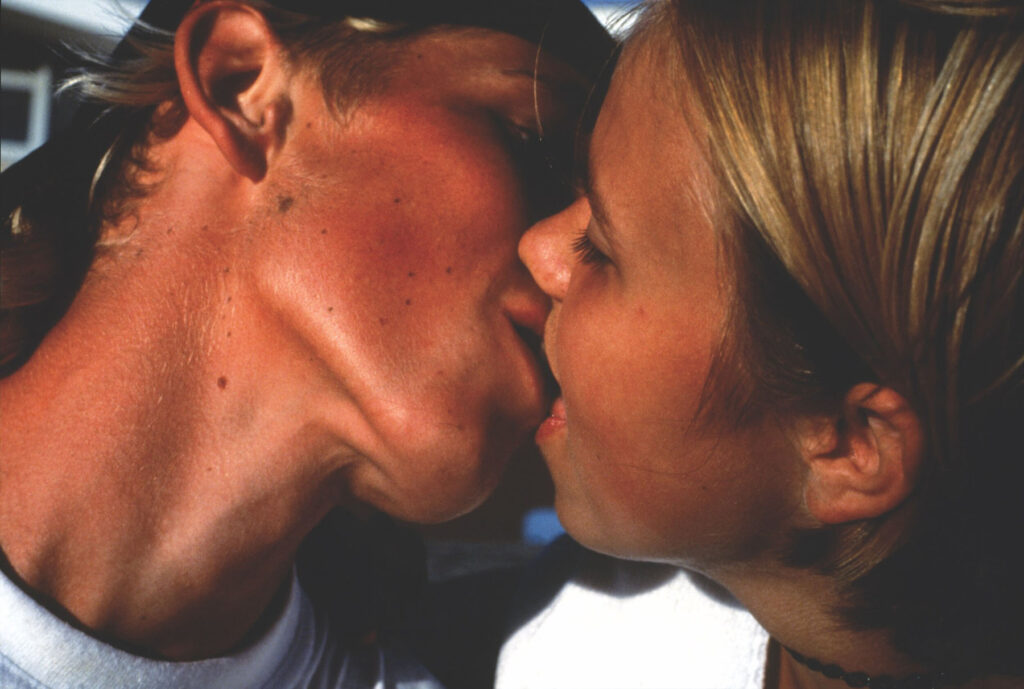

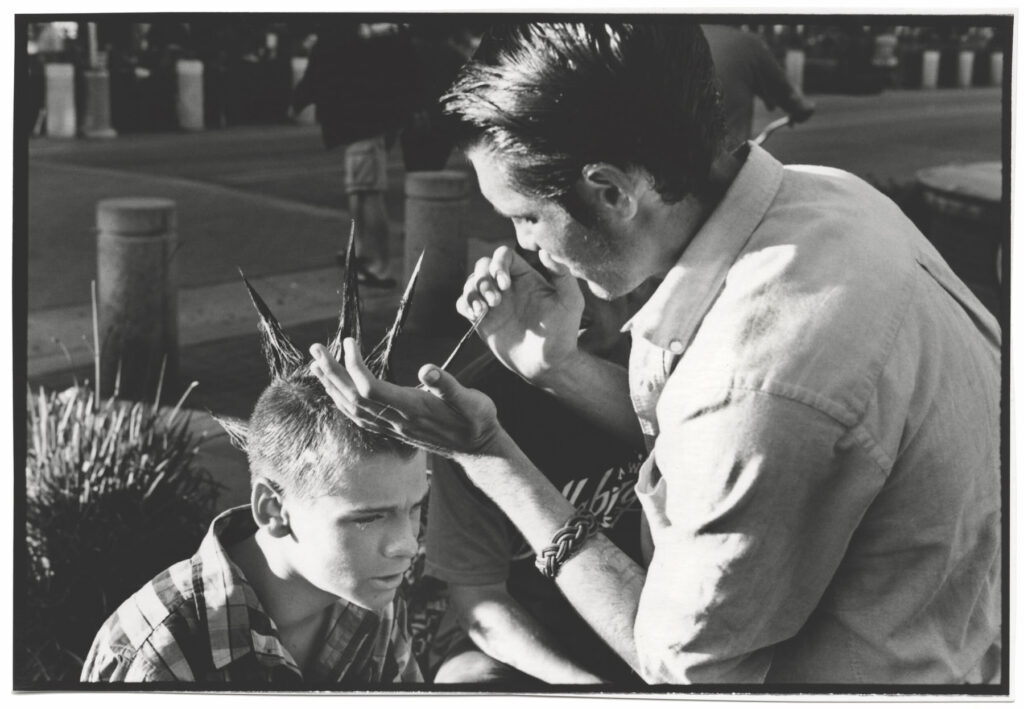

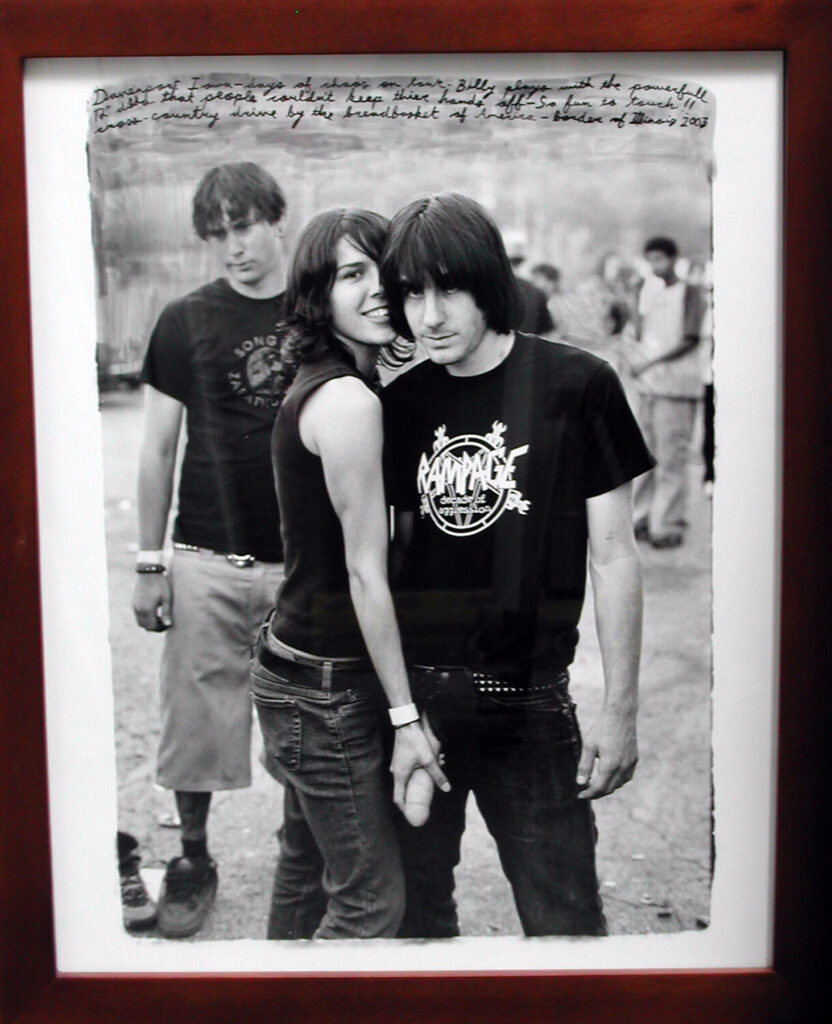

Templeton started his professional skating career in the early 90s, and soon ventured into the world of photography, documenting his friends, surroundings, and the antics that followed the subculture. In the mid to late 90s, Templeton found himself on the frontline of a cutting-edge mixture of personal expression and social documentary. Developing this into a vast and distinct body of work, Templeton has become a household name in the world of contemporary street photography, with his most notable work ‘Wires Crossed’ being part memoir, part documentation of the DIY, punk-infused subculture of skateboarding as it blossomed between the 90s and early noughties.

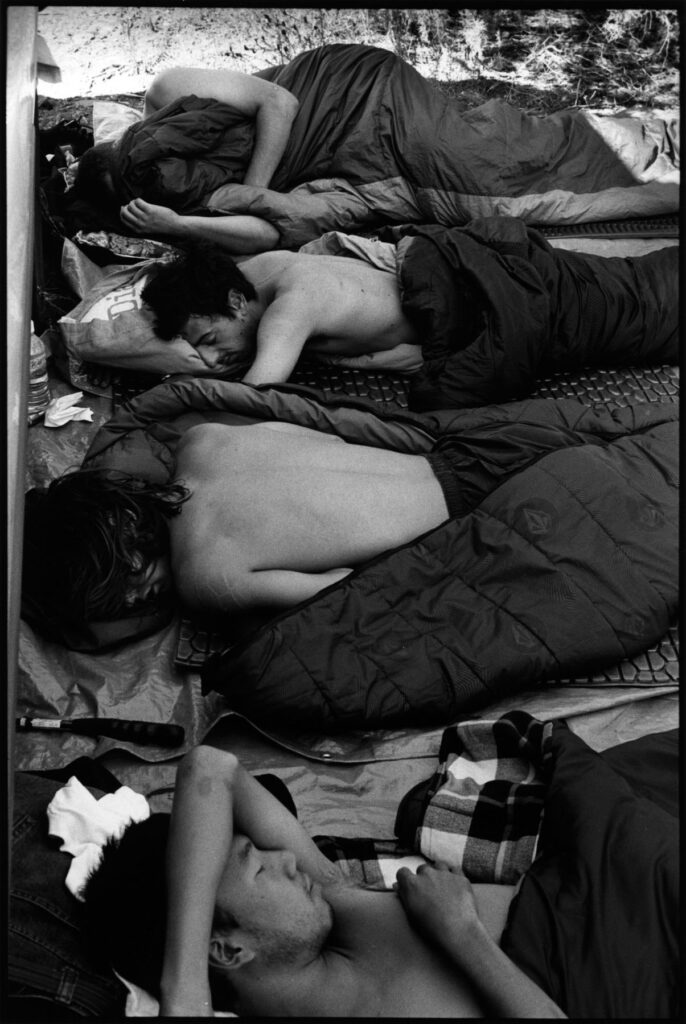

Giving us an insider’s look at a subculture in the making and confirming his capabilities as a visual artist, Templeton’s work has achieved a signature style that has emerged from the skateboarding world he helped establish. Templeton’s approach to street photography and documenting youth culture recalls the iconic work of Larry Clark, Jim Goldberg, and Nan Goldin, and is fuelled by the raw energy of the skate scene and all of its grit and glory.

NR Magazine speaks with Templeton about his life’s work, his thoughts on life on the West Coast and his identity as an artist.

What initially attracted you to working with photography?

In my former life as a professional skateboarder, I was surrounded by photographers whose job it was to take photos of me skating and I was always interested in their cameras, how they worked and was generally immersed in the world of film and photography through them. But it wasn’t until I was exposed to photobooks by Nan Goldin, Larry Clark and Mary Ellen Mark that I really started to see photography in a different way.

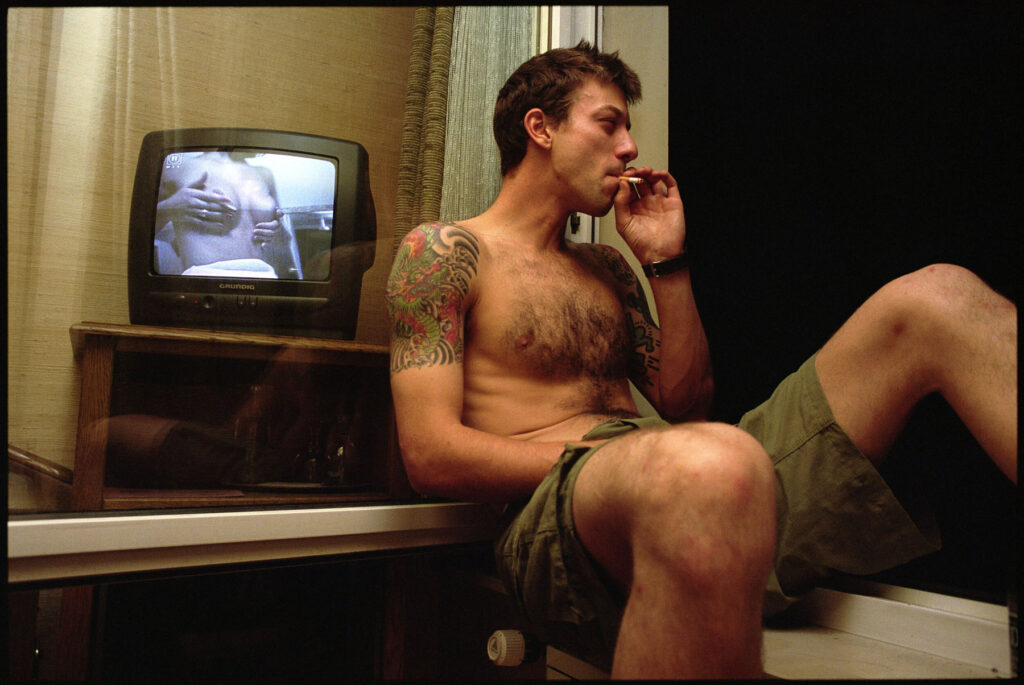

I had always had a camera for taking tourist snaps, but after seeing those books I mentioned, and work from people like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Garry Winogrand, I realised the power of a good documentary photograph. And like any 22-year-old boy, I thought maybe I could do it too. I was traveling the world with some hard-living folks acting like rock stars on the road and I had that personal ‘a-ha moment’ where I decided to document what it was like to be a pro skateboarder from my perch on the inside.

I’ve tried my luck at skateboarding in the past, but for me, I think starting as an adult I’d already developed this strong sense of fear that I struggled to overcome on the board. Did you ever feel this kind of apprehension when starting your artistic career or was it something that just came naturally to you?

A friend once asked me where I get the gall to put artwork out into the world. I think he meant it as a criticism, as in, ‘why do you think what you do is up to the standards of true art and so confidently offer it?’ I think he considered my artwork naive. I thought about it and was aware that compared to many of the artists I admired, my work was naive. I think my answer to him was that one needs to have a certain amount of delusion built into them to get them over that self-critical hump. When you put what you do out onto the chopping block, there’s always someone ready to chop. But there is also always someone who may connect with what you have done and appreciate it, so you do it for those people.

I think years later when you look back on your own work, you should be embarrassed a bit, because hopefully you have evolved and improved. So yes, I have felt apprehensive about my work, but I’ve tried to operate in the spirit of putting one leg in front of the other and to keep moving in a positive, evolutionary direction.

Skateboarding and Toy Machine has been such a huge part of your life and your identity. With your creative pursuits – photography in particular – have you ever felt the need to establish a specific style or aesthetic? Obviously when you first started you were documenting the subculture you were part of. Was that always your aim?

My aim at the beginning was to document skateboarders, but once I had a camera on my shoulder 24-7, that narrow scope quickly widened and whatever was in front of me became fair game to be photographed. My aim regarding style was always Henri Cartier-Bresson, and in that way the aesthetic I was after has always been very pared down – no frills.

Cartier-Bresson was the quintessential documentary photographer known for being a master of composition and shooting ‘The Decisive Moment.’ I still prefer black and white photos over colour. I shoot with a Leica M6 and a 50mm lens with no filters or adornments, not unlike Cartier-Bresson. When shooting, I try to blend into the crowd and quietly shoot like a fly on the wall. Just the basics: get close, make a quick composition, shoot, then keep walking.

I feel like I wasn’t consciously trying to adopt a specific style, because by default there was no way my work could mimic Cartier-Bresson, Larry Clark or Robert Frank because I was living in a different time period with totally different subjects and surroundings. I did decide to generally shoot in black and white, and to keep it very simple. Starting in 1994 when I started shooting skateboard culture, I was simultaneously shooting many different long-term projects that have continued until this day.

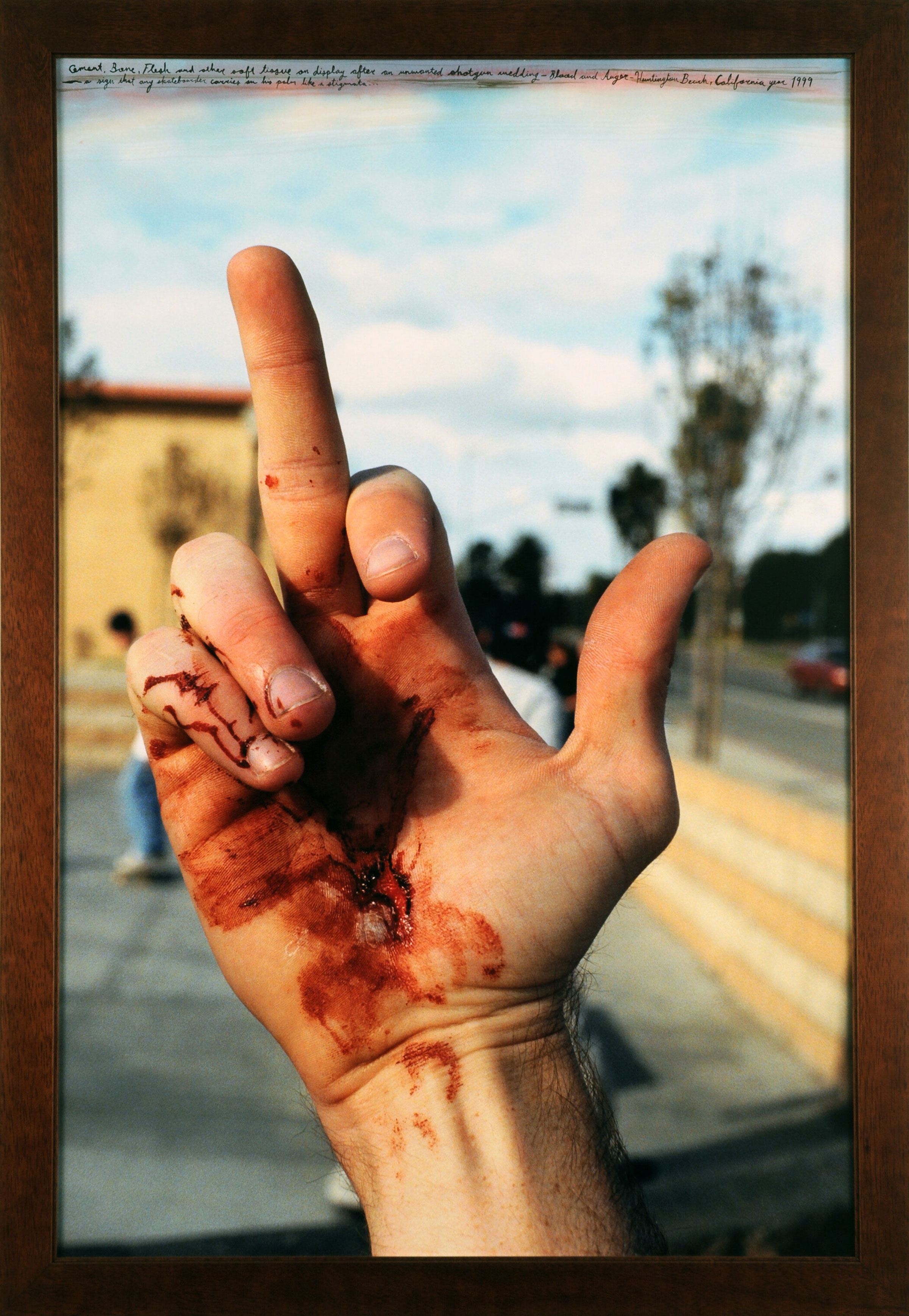

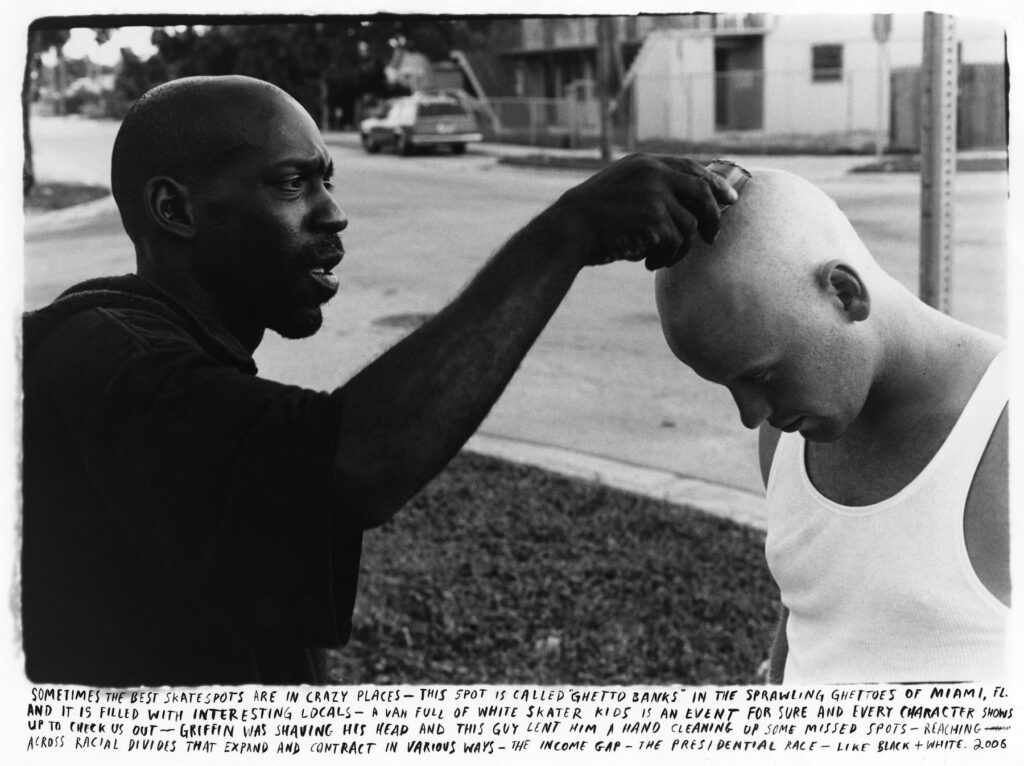

Another aesthetic thread in my work is the idea of writing and painting on the prints. That is a departure from the Cartier-Bresson ethos, he would have frowned on the idea of drawing attention away from the photo itself. But for me, the print itself is an object to be used in any way possible to convey the story you want to tell, even if that means some contextual text or some decoration will elevate it to another level. Artists like Peter Beard, Jim Goldberg, later Robert Frank, David Hockney and Allen Ginsberg all used the photographic print as a starting point to make new types of artwork.

Your documentary project ‘Wires Crossed’ is essentially your life’s work, and you’ve got plans to publish and exhibit it at some point. How do you feel when reflecting on this long-term venture?

It’s a daunting task trying to edit down the five thousand photographs that I have collected over the last 27 years, scattered over all types of formats into a relatively concise, readable, cohesive story. I have had to break it down into themes like ‘Fame in a Microcosm’, ‘Self-Medication’, ‘Lust’, ‘Injuries’, etc. In this way I was able to craft chapters that tell the stories I’m trying to convey photographically on those topics. I have also dredged my journals from those periods so some contemporaneous stories and texts scanned directly from the pages will be included along with the photos.

What have been your favourite places to photograph?

No place jumped into my mind immediately. It’s really fun shooting in Japan. It’s a camera culture so people don’t seem weirded out when you are taking photos there. Any place where I can just walk and shoot is my favourite – even my own hometown.

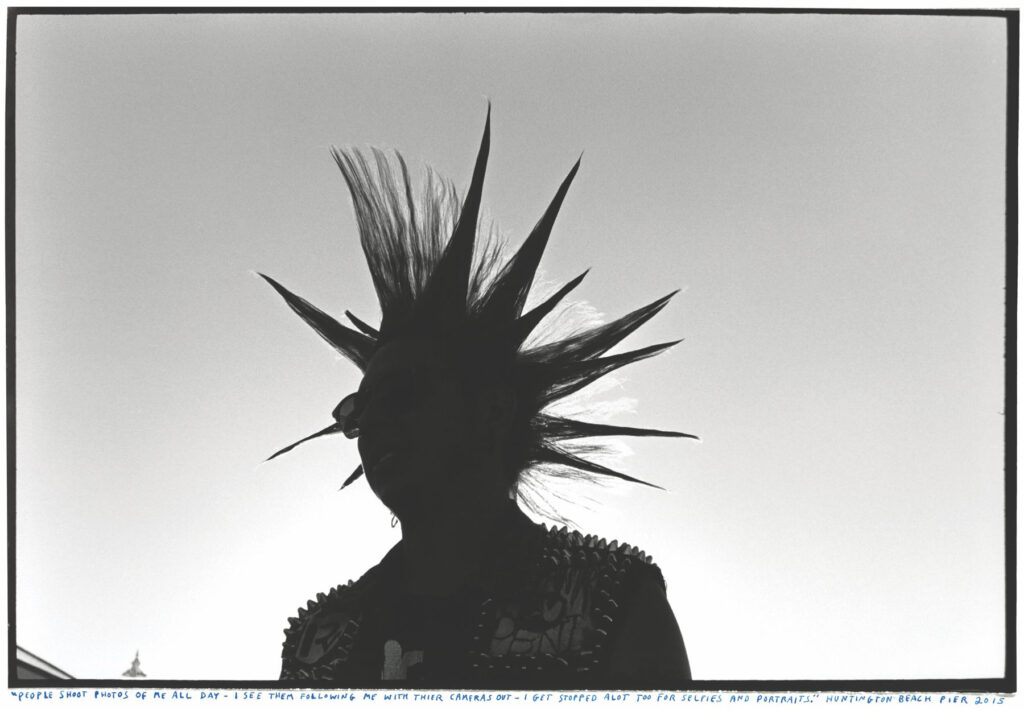

Your project ‘Memory Foam’ reflects on life in Huntington Beach, California. What stands out to you most about beach culture and suburban life on the West Coast?

Suburbia is a fucked-up place, and Huntington Beach is hyper-fucked. It was through world travel that I wanted to look at where I lived in the same way I see a new country. Each time I would come back from a month abroad, I would marvel at the size of Los Angeles and its surrounding exurbs. The freeways are so wide, there’s a seemingly never-ending sprawl. The things we take for granted because we grew up here are things that a first-time visitor here might marvel at, like I do when I see a cool sign or experience a new custom in Asia or Europe.

Orange County, where Huntington Beach is located, was built on the ‘White Flight’ leaving Los Angeles in the late 50s, and those roots are evident, as this county is a conservative stronghold in a mostly liberal state (there’s plenty of white supremacists and their sympathizers here). Over the last four years as American society as a whole has become more antagonistic and belligerent, my hometown has become a surreal ‘idiocracy’ on one hand, and then on the other it’s a beautiful paradise that many people around the world would saw off their right arm if it meant they could live here.

Let me give you an example. As the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic raged, we had the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing racial justice protests in cities all over the world. A BLM protest planned for Huntington Beach spurned a ‘Defend Huntington Beach’ counter-protest in response organised by Tito Ortiz, a well-known retired MMA fighter. The popularity of his ‘Defend Huntington Beach’ movement launched him into a run for city council, where he overwhelmingly won a seat and was named mayor pro-tem. Of course, he is anti-vaccine, thinks Covid is a ‘plandemic’, and refused to wear a mask at the council meetings. We basically had our own mini-Trump here inside Huntington Beach city government like a bull in a china shop.

Naturally, he resigned months later after realising running a city is actual work, and he couldn’t take the constant heat his antics provoked. Each weekend at our pier there’s a mini rally by adherents of some disgruntled group, usually a combination of Pro-Trump/Anti-Covid/Anti-Vax/Extremists that yell at people as they walk by on their way to the beach. Maybe I’m just overly sensitive to all of this, but that is what I want to document. The dichotomy of this place is essentially a microcosm of the whole United States. I think my series started off as a sincere and earnest documentation of my local environment and has ended up being a critical look at human nature.

Whenever I end up publishing this work, I think it will reflect a love/hate relationship with my hometown.

With the theme of this issue being Identity, I’d love to know how you see yourself as the person behind the lens.

I see myself differently at any given moment. Sometimes I see my physical reflection in a window and I’m horrified, revealing that perhaps my mind’s eye sees a younger version of myself and I’m shocked at the creature I inhabit currently. It probably effects how I approach shooting photos in the streets because I am hyper aware of what I might look like to an outsider as I am walking around with a camera.

“One moment I am shooting in a spirit of celebrating human nature, another I have turned cynical and critical.”

The identity I imagine myself having is certainly different than the identity I actually have in this space. But to answer the question more directly, when I’m behind the lens I try to see myself as an inquisitive onlooker. Not a passive onlooker, but a participant in society – a member who happens to be using a camera, which isn’t so strange anymore since we all have them in our pockets now.

If you could select a handful of works that capture the essence of your creative vision, what would they be?

Photographically, something like my last major book ‘Tangentially Parenthetical’ would probably the closest thing to the essence of what I’m trying to do currently. Of course, that essence is evolving, and I’m sure the forthcoming ‘Wires Crossed’ book will be the closest I can get to my creative vision, since it’s the body of work that got me into photography in the first place.

A lot of your work is in black and white. What attracts you to working with this aesthetic?

I think colour is amazing, but for me, more often than not when I shoot in colour, I wish the photos I got would have been in black and white. Once in a while, the colour pops and makes the photo even better, but often the colour comes off garish or gaudy. I prefer to strip everything down to the essentials. Maybe I have a strong infection of nostalgia in me. There is a timelessness to black and white that I like.

There’s also a practical reason – in my home darkroom I am not set up for colour. I tried once but it was a big hassle, and the chemicals are much more toxic. So, with black and white I can do everything from home which is nice.

Your work also features more intimate pictures of your wife, Deanna. Does your visual approach change at all when working with someone closer to you?

I don’t think it does. I have a camera on me when I’m out, and there’s always one laying around when I’m at home. So just like if I were out in public and something visually interesting happens and makes me want to shoot it, the same applies when I’m at home.

If something happens that is out of the ordinary, let’s say Deanna is vacuuming the house nude for some reason, I’ll shoot that because it might be funny or interesting to me, but it also might translate into a photograph that speaks to the domestic experience and will resonate with others who have a similar shared experience.

I suppose my approach at home is more sensitive, although if this body of work ever comes out, it will be a fairly unflinching look at married life. The work is called ‘Suburban Domestic Monogamy’.

Would you say that being transgressive and incorporating a DIY aesthetic into your work are important aspects of your identity?

I have this one identity as a pro skateboarder of 22 years, and another as an artist, and they overlap to some degree. Through my skateboard company Toy Machine’s graphics and advertisements, I have always tried to poke holes in the whole idea of selling and marketing something you love and care about, it seems so crass, so I made it into a joke about brainwashing our loyal pawns into doing our bidding, using language that Nike or Amazon only wishes they could use!

We have a ‘Consumer Control Centre’ with its own logo, and it’s all about forcing consumers into blindly buying only our products. Our fans are in on the joke. We don’t take ourselves too seriously.

“It’s just skateboarding – but Skateboarding is our life! I’d like to think the same applies to the art world.”

It’s just art, but art is our life! It’s all for fun and enjoyment but it’s also our life blood and the thing that keeps us going, so I think there’s a built-in spirit of transgression in what I do that stems from skateboard culture, and of course a do-it-yourself attitude is also endemic.

On the spectrum of transgression, I feel like I’m pretty mild. I wouldn’t say that anything I do ‘breaks the rules’ in some heroic way, but I think it does break down the façade between the artist and audience or company and the customer. We are all part of the same community. There’s no hierarchy – or at least there shouldn’t be.

Have you ever thought about dabbling in other creative fields?

I have been recruited as a commercial film director, but I never pursued it seriously as of yet. I dabble in commercial photography here and there. I would like to get into proper filmmaking, and I might do OK in marketing since I do that already on a small scale for Toy Machine.

Are there any particular works that resonated with you when you first got into photography?

I mentioned Goldin and Clark, but once I got into photobooks there was a cavalcade of falling in love with so many photographers’ work! Anders Petersen, Tom Wood, Susan Meiselas, Jane Evelyn Atwood, Graciela Inturbide, Bruce Davidson, Robert Frank, Peter Beard, Jim Goldberg, Bill Burke, Burk Uzzle, Josef Koudelka – there’s too many.

More specifically I’d say that ‘Raised By Wolves’ by Jim Goldberg, ‘Brooklyn Gang’ by Bruce Davidson, ‘Falkland Road’ by Mary Ellen Mark, ‘At Twelve’ by Sally Mann, ‘Nicaragua’ and ‘Carnival Strippers’ by Susan Meiselas, ‘Streetwise’ by Mary Ellen Mark, and of course ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’ by Nan Goldin, and ‘Teenage Lust’ by Larry Clark were some books that really hit home for me. Those are ones off the top of my head.

What things have inspired you recently?

I discovered Tom Wood – see ‘All Zones Off Peak’ and ‘Bus Odyssey’. All work by Mark Steinmetz, Alec Soth and Gregory Halpern. More recently I have discovered older work but new to me from John Humble, Sage Sohier, and Larry Fink. There are also some young photographers making great work that are really cool; Daniel Arnold in New York, William Galindo in Los Angeles, Jake Ricker and Austin Leong in San Francisco, Billy ‘Captain Soncho’ Williams in Orange County. Deadbeat Club Press is publishing a lot of great photographers’ first books. It’s not new, but I’m also really getting into the German New Objectivity movement, especially Otto Dix. There’s a painter in Los Angeles you should check out named Kevin Christy.

What’s your usual approach when taking a photograph?

I prefer to go completely unnoticed. Usually, I am just walking by at full speed and shooting as I go. Sometimes it’s a direct approach where I walk up and start shooting and start a conversation. Sometimes I ask for a portrait, but mostly I just shoot and keep walking, and most of the time I am not seen.

Have there been moments when you’ve regretted not bringing a camera with you?

Every time I forget my camera, I have regretted it. Life isn’t worth living if I can’t take a photo of it. I say that jokingly but that is really how I feel. Even if I forget the camera, I still have my iPhone and can shoot photos, but only for Instagram. I don’t use digital photos in books or shows, although there have been a few exceptions. I did a very tiny book with a French publisher of some of my digital photos from before I had an iPhone as a special project, and a few years back I did an exhibition at Pilgrim Surf Shop in Japan of my #DailyHBpierPhoto shots from Instagram.

Have there been any difficult moments you’ve had to overcome when taking certain photographs?

I have had some strange moments, but nothing too crazy. I shot some teenagers fighting in Huntington Beach once, and in theory as the adult present, I should have broken it up, but it was so damn stupid how it started and what it was about that I figured they deserved to fight each other.

Another time in Barcelona I shot the police roughing up a suspect as they were trying to arrest him. They banged his head on the side of the police car. One of the cops saw me and made me give him my film. I wasn’t in the mood to make a stink about it, so I just handed it over. Luckily, I had just put a new roll in so I didn’t lose anything special.

Do you have any daily rituals or habits that help you stay creative?

I get up each day and procrastinate for way too long, then check my emails, and whatever is the most pressing or has the most looming deadline is what gets worked on. It may be graphics for Toy Machine, a painting, drawing, or organizing the photo archive. It’s in constant need to improvement, even when I’m not shooting as much. Covid has slowed down my photo taking, but not my archiving and editing.

I need to adopt a daily ritual; I think that would be very helpful for me. Maybe I could spend 30 minutes making a drawing every day? But think of the 365 drawings you’d have if you stuck with it.

Looking back on your career, both as a creative and a skateboarder, would you take the opportunity to do anything differently?

In hindsight I would have started skating and making art earlier. If I could go back in time and find a young Ed, I’d tell him, among many other things, to start making art now, start skating now, and keep a journal. I keep a spotty one, mostly for travels, but it’s not philosophical, it’s just the bare facts of each day. The people who know where they want to go tend to get there over time, so an early start helps.

I don’t have a lot of major regrets that I’d want to change. It would just be small things, dead ends that I may have avoided. But having said that, those dead ends, and mistakes are what forms you into the person you are. Can you imagine going through life never making a mistake? I wonder if anyone has. Mistakes are learning experiences.

What can we expect from you in the future?

In the near future I have a book of my drawings coming out in December published by Nazraeli Press. In January 2022 I will have a solo show of my paintings tentatively titled ‘The Spring Cycle’ at Roberts Projects in Los Angeles, and I’ll take part in a group show at Tim Van Laere gallery in Belgium.

Later in 2022 the ‘Wires Crossed’ book will come out, published by Aperture in the fall. The ‘Wires Crossed’ exhibition will start in the Netherlands in 2023 at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht. We have plans to travel the exhibition both in Europe and in the USA. After that, it’s safe to expect some more photobooks!

Discover Ed Templeton’s work here ed-templeton.com