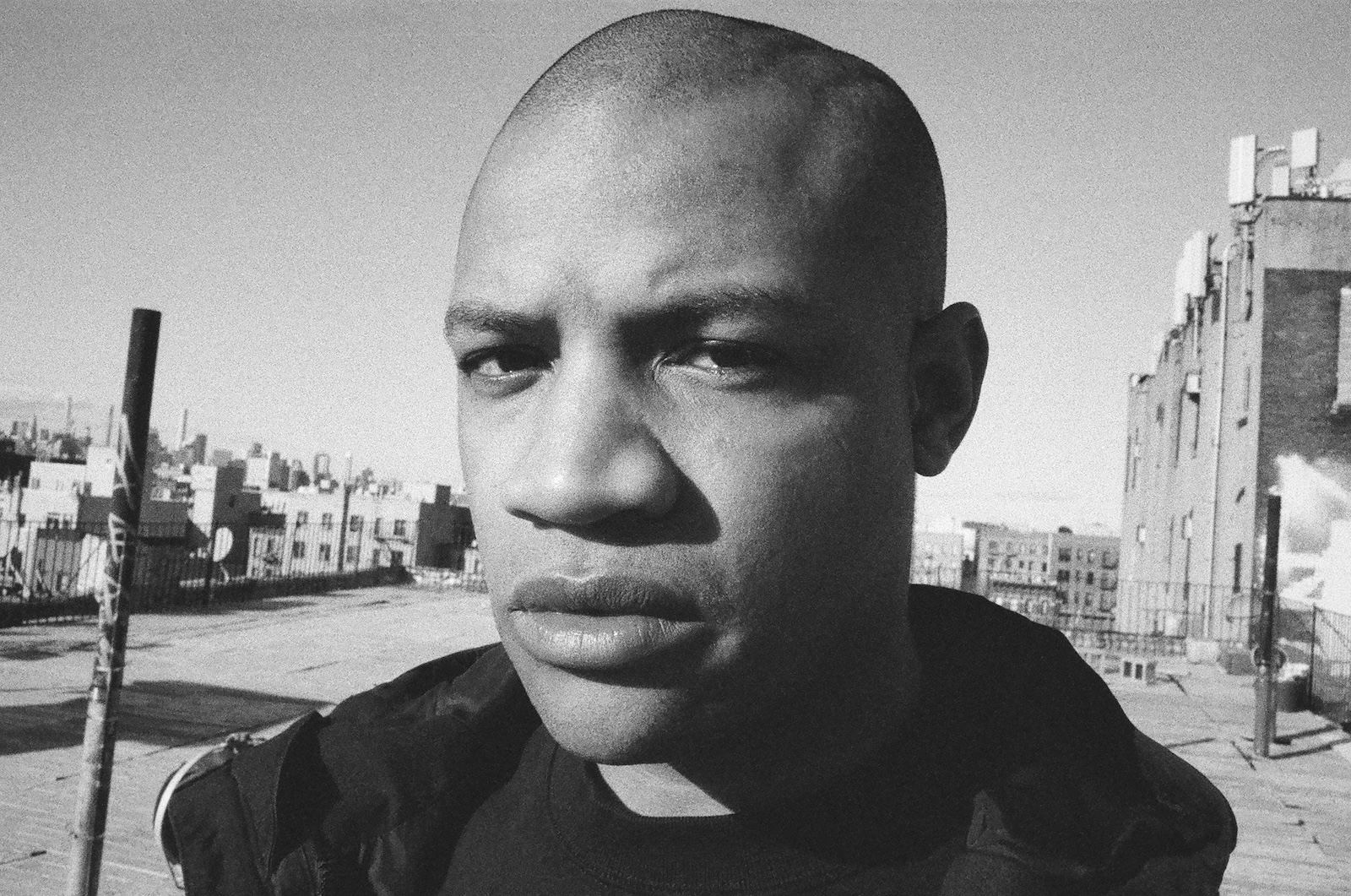

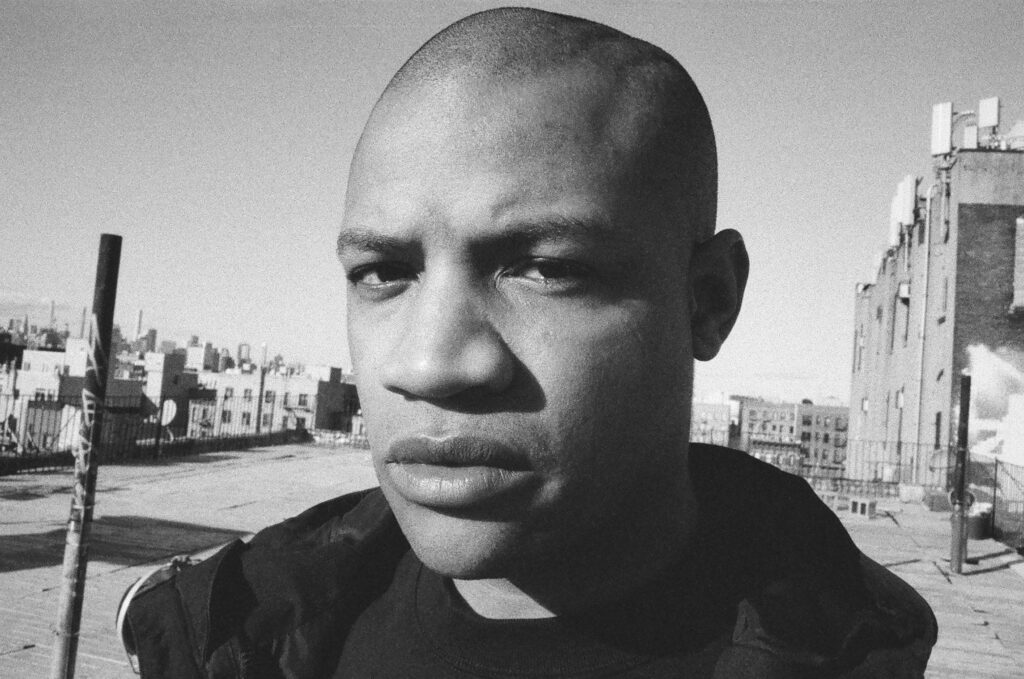

MoMA Ready Is Vouching For Himself

MoMA Ready doesn’t care about keeping up with the perceived glamor of electronic music. He just wants to be able to show up in a white tee and black sweats to work, and that’s exactly what he’s sporting when he shows up to The Lot Radio to meet with NR Magazine on a sunny Thursday afternoon, and that’s what he feels comfortable wearing when he’s DJing all over the world.

He’s ultra laidback while he tells his story. He takes his time rolling a blunt and gets too distracted to take a puff as he narrates the moments of trauma and heartbreak that led to where he is today. The producer is from Newburgh, New York — a place with one of the highest crime rates in America.

“I’m from a fucking horrible environment,” he said. “I’m not from a nice neighborhood in the suburbs. I got to art school because I’m talented.” He studied filmmaking in New York City’s School of Visual Arts before fully pivoting to music in his final year. Soon thereafter, the artist—born Wyatt Stevens—stepped into becoming MoMA Ready.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: Does filmmaking play a part in your production process at all?

MoMA Ready: I have a very visual brain like in full color. Very visual. I can see everything I think about. But I’ve always been multi-faceted. I got into art school with a four-legged portfolio. I was doing video work, graphic design, photography, and fine art. But I felt like filmmaking was a medium where I can express all those factors.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: Do you feel like coming from a working class background and not having the same resources as other students in school informs the choice to stay an independent producer?

MoMA Ready: Yeah, but I think it more so comes from not wanting to be told what to do. I would love resources. But even when things have benefited me, if people are trying to tell me what to do, there’s a part of me that’s instantly like, “Fuck off.” I have a rebellious nature, but not in the traditional sense. I’m not edgy and I don’t have a desire to be provocative. I’m not trying to shock and awe. I just don’t necessarily want to have to present myself a certain way in order to be successful. Why sacrifice my integrity if I don’t have to? I’ve gotten this far. I’ve accomplished a lot.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: How old are you anyway?

MoMA Ready: I just turned 30. What about you?

Arielle Lana LeJarde: I turn 29 next month. I see kids coming up in the scene and they’re like 19, so I feel like we’re old.

MoMA Ready: I feel like our generation is the most important generation. I like to think of us as a bridge between this old version of society and this new version of society. Older millennials are the reason why social media exists. So I have zero shame about being this age. I’m the perfect age because I have this knowledge that this older world exists.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: Speaking of the older generation, we just learned the heartbreaking news that DJ Deeon died today. How did he inspire you and your music?

MoMA Ready: It shouldn’t be a thing where people like DJ Deeon and Paul Johnson are passing away from health issues. People who are pioneers should be as taken care of as well as big headliners. It puts a lot of things into question for me and I think a lot of people treat this as symptoms of how they feel about the people that benefit. Because of the narratives that have been spun out of capitalism and white supremacy in these spaces, the wrong people end up suffering.

DJ Deeon, and other people from his graduating class, created the foundation of the movement that my friends and I have created, and are even able to stand on. Deeon was one of the OGs that embraced us. He embraced all of us on an individual level. And he was supportive. There’s a lot of animosity for younger generations and he was never on that type of time. It’s sad. I wish I could have seen him live one last time.

DJ Deeon is a big influence on myself and my friends in the rhythms and everything that we do. So losing one of my main influences is hard. There’s not going to be someone that comes along and fills it. And I don’t have to say this just to give him respect because he passed away. He was that before he passed. All of this just solidifies his legacy.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: Why do you think some people in the older generation of producers and DJs aren’t as accepting?

MoMA Ready: I want to blame them because they’re adults, right? But it’s not their fault. They’re mad at me—or whoever that they’re angry at—because of the structures that I just mentioned. Not because of us.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: When did you start producing anyway?

MoMA Ready: I really started experimenting with producing around 2013, but I had tried way before that. It wasn’t really about making music until 2016, when I experienced things in my personal life that made it hard to focus. Music was the only thing that kept me grounded.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: What happened in 2016?

MoMA Ready: I was a victim of violence. I was suckerpunched downtown and the person broke my face. They kicked me in my face and I almost died. That’s why I have a metal plate in my face. It just made me recoil because a bunch of people that were supposed to be cool with me didn’t help me at all.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: A lot of your career surrounds your collaborations and your friends. How did you learn to trust people again?

MoMA Ready: Things in my life tend to resolve themselves pretty aggressively and serendipitously, so I learned to embrace that. I learned to take those steps on those serendipitous stones. There were also certain people that became consistent in my life and I just realized that nobody was out to get me. I have people I work with, I have my friends, and we all luckily can keep pace with each other. So I’ve tried to take advantage of the blessings that I have.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: With being in AceMoMA and having a close group of friends who are all equally as prominent, do you ever struggle with wanting to just be recognised as a standalone artist?

MoMA Ready: Hell yeah! I’m very vocal about it. I’m super honest and a very transparent person. I’ve even spoken to AceMo about it and all my friends. None of us would work if we weren’t singular artists. We all have to have individual careers. It’s important. But my problem was, I was putting my work into everyone else, so everybody started outpacing me in a way that made me wonder what I can do. I started just focusing on myself.

I recently went through a breakup that made me ask myself, “Who am I outside of other people?” I put myself into a lot of people. Then, I started vouching for myself because I realized nobody else is going to do it. What I contributed to the local space in New York, based on the proximity of being near me—because of my label, my compilations, and my efforts. I don’t give a fuck if it sounds cringe, but I’m owed. And I’m taking it now.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: What do you want people to know about MoMA Ready and what do you want people to know about Wyatt Stevens?

MoMA Ready: MoMA Ready is a persona. Don’t think that because you listen to my music that you know me at all. And it’s not because I’m trying to not know you. It’s more so that you need to approach me as someone that you don’t know. I understand that, especially with the way that I am on social media, I’ve built a lot of parasocial connections with my fan base. I answer their questions. A lot of artists are very like yeah, I’ll let you know what’s weird. Like forever. I feel like because I’m so honest with people in these questionnaires like people feel like they have a literal relationship with me.

About Wyatt Stevens? I’m a complete human being.

Arielle Lana LeJarde: How would you describe the New York City dance music scene and what is your part in it?

MoMA Ready: Shit. It’s a special place right now. New York City dance culture is now what people used to think it was. Nightlife has always been happening here, but I think as far as dance music is concerned, I want to say it’s never been like this anywhere in the country. I’m probably definitely wrong, and some old head is going to think I don’t know what I’m talking about. But for my generation, we’re doing a really good job of maintaining the culture and being expressive and making sure that the real is still here. I’m thankful to be a catalyst in that. I know I’m not the only one, but goddammit, I’m a big one.

Credits

Photography · Sam McKenna