You completed your project, The Ameriguns, three years ago, but you were just in the United States a few days ago. How did it feel to be back?

I was in Washington DC for National Geographic, which is based there. They were having their annual meeting, so I stayed for five days before going to Los Angeles for a few meetings. Work-wise, it’s a good city. I always find good connections there, especially since I’ve been working for NatGeo since 2016; in their building, you can meet a lot of really interesting people who go in and out, whether photographers or explorers. When I started being a photographer, I wanted to work for National Geographic, so when that happened a few years ago, it was incredible.

Do you travel there a lot?

I actually come to the states pretty often, and I’ve been back a couple of times since I took my last picture of the series (in January 2020). I’ve been going there for the past 20 years, and it’s the place I’ve been to the most outside of Italy — I’ve probably been there more than 40 times. On my first road trip to America, I went to Houston and drove to Austin, and on the drive, I probably saw 20 gun shops on the sides of the roads. That stuck in my mind. I would see McDonald’s, and then a gun shop, and then Mcdonald’s and a gun shop.

The late writer and critic A.A. Gill wrote in his book, To America with Love that ‘Guns in America’s story are a constant, a plot device, like coffee cups in European films. Guns are Hollywood’. Your work depicting Americans with their firearms sparked considerable conversation. How did that all start?

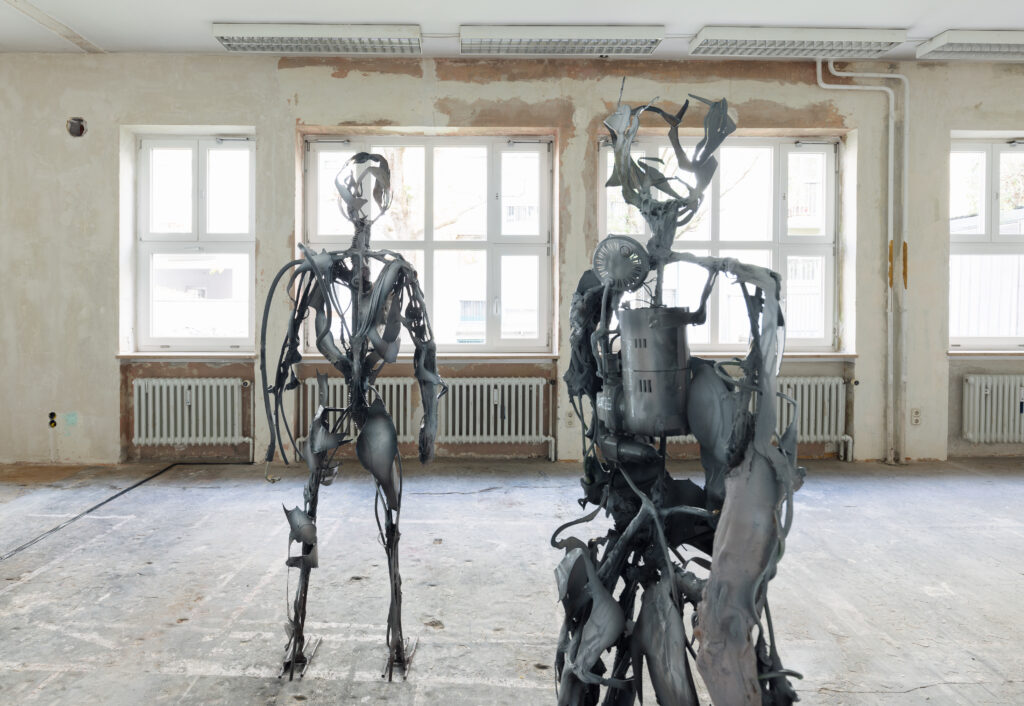

I was in Kansas for a National Geographic shoot four years ago. On one of my days off in the middle of November, I was driving outside of Kansas City and saw a huge gun shop in the middle of nowhere. For the first time ever, I walked in. I was curious to see what was inside, and when I entered, I realised they didn’t just sell handguns but war-level firearms. I started to speak with some of the customers, and one of the customers was at the counter. I asked, ‘Is this the first gun you are buying?’ to which he replied, ‘no, of course not, I have more than sixty’. It came to me to ask, ‘can I come to take a picture of you and your guns’. The first photo was completely natural, without the project of Ameriguns in mind. A few days later, it happened again in Dallas, and I decided to do some research and immediately found out the numbers.

Your images in this series conveyed these numbers more than just people and their guns. What numbers did they show?

In America, there are more privately-owned guns than people. There are 1.3 guns per person in America, but then you discover that only one-third of Americans own guns; that means there are five guns per person who owns a gun. Then, counting all the privately-owned guns in the world, 48% of them are in the USA, which constitutes 4% of the global population. It’s a lot, so I thought, I want to photograph these numbers.

You quite literally put the statistics and the facts on the floor. What were your intentions for the series?

I wanted to understand more, so that’s what I did. After mass shootings, there would be waves of popularity for my photos, going onto Twitter and on the media. Mass shootings are a huge problem in America, but it’s not, in my opinion, the biggest problem related to firearms. Analysing the 2018 statistics, there were nearly 40,000 gun-related deaths, and 77 people were due to mass shootings; the larger number of people (more than 100 people dying every day from gunshots) is almost normal. But, with mass shootings, especially in schools, the media talks about it.

Out of the 500 people I contacted, I ended up photographing around 50 people. I went pretty much everywhere in America and photographed in 32 states. There are many things I liked and photographed in the country, so it wasn’t the only project I made there, but one of the aspects of American society that triggered my curiosity was their relationship with guns.

This bare-bones bluntness to the concept has translated throughout many of your series, including your work with National Geographic. How does this line of work with National Geographic differ from your personal practice?

It’s really stimulating working for them. I’ve taken three assignments from National Geographic, and you work alongside the photo editor. You create a conversation with them, and when you reach an idea of how you want to create the story, then you go and shoot it. It’s one of the best work experiences I have had in my life. It is a magazine that cares a lot about photography and the quality of work they publish. The people there know what they do, and the whole team are great.

Many of your compositions have an intimacy that glazes over nostalgia and incarnates a realism in subject matter and context. When did you begin formulating your distinctive style?

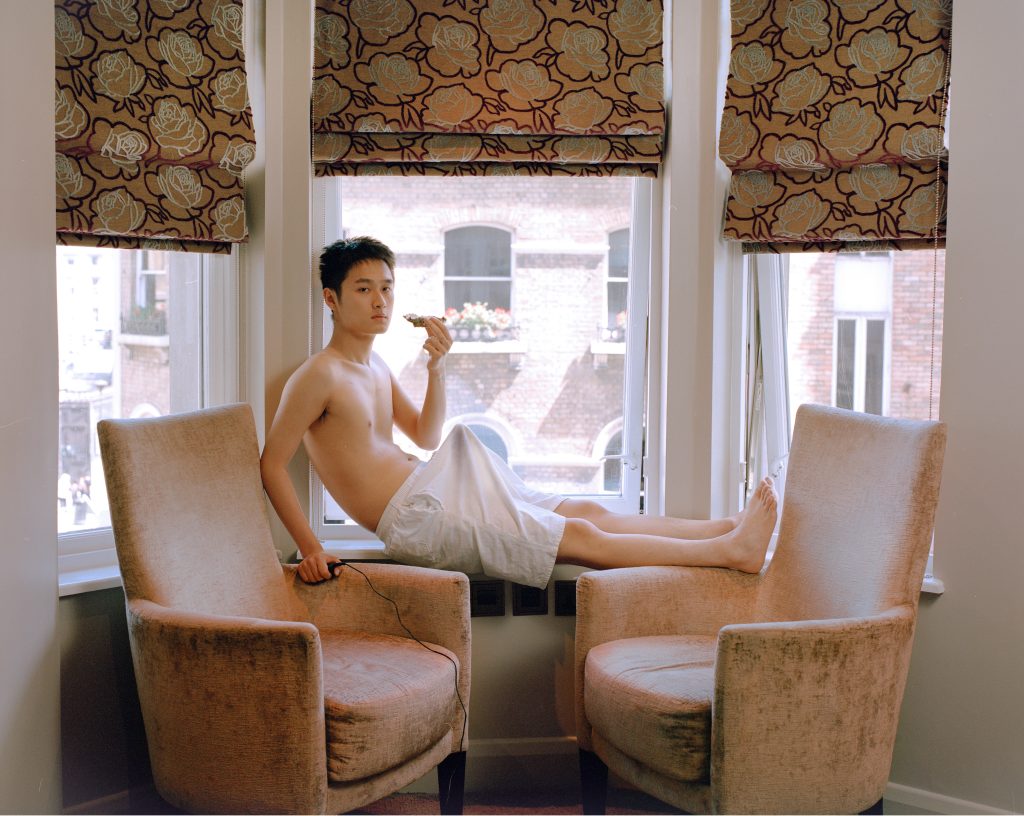

The love I have for photographing people in their homes started in 2009-10. Over those two years, I was working for the Italian Magazine La Republica. I made a project, Couchsurfing, where I travelled for two years all over the world — over 50 countries, I think — and I used the Couchsurfing social network (a sort of Airbnb for free). I was hosted by people in 58 countries, reporting stories for the magazine from a person’s home, and every week had a new chapter in a different place. The story was about the host and their life for a week. I would take photos, maybe go to work with my host or visit the school with them and take photos.

You take photographs that are about something. They are more than what they are of and step outside the realm of literal relation into a heightened contextual language. How did your view as narrator come into the picture with Couchsurfing?

It was amazing because I got to do this work across Africa, Asia, Alaska and everywhere. That was the first time I pointed the camera towards normal people and normal lives. Beforehand, I was always looking to find special stories that were of interest and the media’s interest, but when I did Couchsurfing, I thought, wait for a second, this is interesting; it’s interesting watching normal people’s lives because you can learn a lot of things from them. I was super lucky to have the opportunity to do this project for two years in so many countries, meeting people from different religions, different cultures and different everything: each place gave me a different piece of something. I was so curious to see how these people lived, and I wouldn’t take my camera with me all the time; there were days I wouldn’t bring it with me because I was just living with these people. I never take pictures of somebody without knowing them, I need to understand something about them to photograph them.

Does this stripping down to the essentials create a narrative? What makes you most engaged with your work?

What I really love to do is photograph people where they live. I like to enter people’s houses and take photos of that person where they live in their environment, and that’s the common line in all my projects. But I also like to work in advertising and creating sets from zero. Sometimes, I’ve shot a few campaigns for clients where we created scenes out of nothing. In that case, it’s more of a collaboration where I am there as the photographer, and then there are set designers who fill the scene. With people in their homes, every time I do a project, I tell my subjects that they have to be patient. I’m not going there to take a snapshot, I’m coming to take one or two days of your life. It’s always a collaboration between me and the subject.

Do you believe that your work is emotional? Is the human reaction simply an outcome of images created to solely inform?

Yes, I think some of my stories are emotional. Everybody can have an emotional reaction to every story, so it depends upon the person. When I present my work, I always see people getting close to my work, and they do react. I’m happy to see people being emotional about what I do and what they say. Whether they are reading my books or at my presentations, it’s nice to feel that what you do has a sense of meaning. It means you are going in a good direction.

What project makes you most emotional?

My grandmother’s book, In Her Kitchen: Stories and Recipes from Grandmas Around the World. I grew up with my grandmother, and there are lots of memories related to that book. The reason I made the book was that, while I was travelling for my Couchsurfing project, my grandmother was extremely worried about the food I was eating. That was her only concern, and so I said, don’t worry, ‘I am going to have dinner with other grandmothers because they know how to feed me for sure’. So, I started taking these photos of recipes and of the grandmothers every week, and I was sending these photos to my mother and my grandmother. My grandmother would relax. And at the end, I looked over all these images and recipes and thought I could make a book out of them, so I did it. I think it’s my greatest success because they printed 25,000 copies of the book in English, and it sold out, and then we had 14 different editions in different languages. It’s weird because the book is a cookbook and not a photography book, and there are photos in it, but if you look for it in a shop, it is in the cooking section. I made it because it was a homage to my grandmother. I remember going back home to her and telling her about my trips and the food that I tried, and sometimes I would cook some of the recipes for her to try.

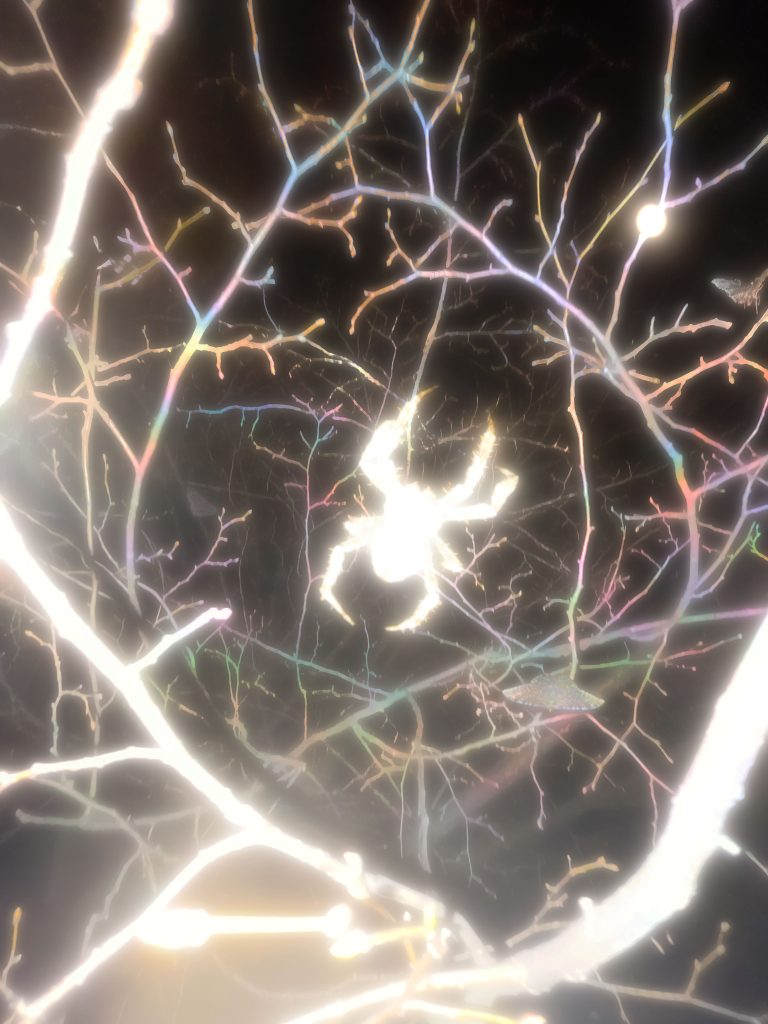

Honing into your series Home Pharma, what was the impetus to capture the relationship between person and pill? Is this a very personal relationship?

It’s personal because when you show the medicines you use or have in your house, you have them because you have certain needs or fears. It really opens the door to intimacy. That was a project I worked on for National Geographic when they were preparing an issue about Health. I proposed the idea of going to 20 countries and looking at what medicine people had in their homes. It was easier to ask people to show me their medicines rather than guns, but when you show such a thing, you say a lot about yourself and where you live. Certain countries had people that tended to rely on medicine a lot, but other countries had less trust in them. The places where I found strong relationships between medicine and people were France, Switzerland and the United States. It doesn’t happen as much in Africa or the Caribbean.

Is it hard to find a balance between the intimate subjects (and their possessions) with their presentation?

It was interesting to see that while I was shooting, people would lose their shyness and end up bringing out more and more of what they had in their medicine cabinets. It was a step-by-step process as people can be protective and not want to show you everything. It is an interesting way to measure shyness and fear.

Your images are uncondescending and honest. Does their formal composition shift often? Do you still experiment?

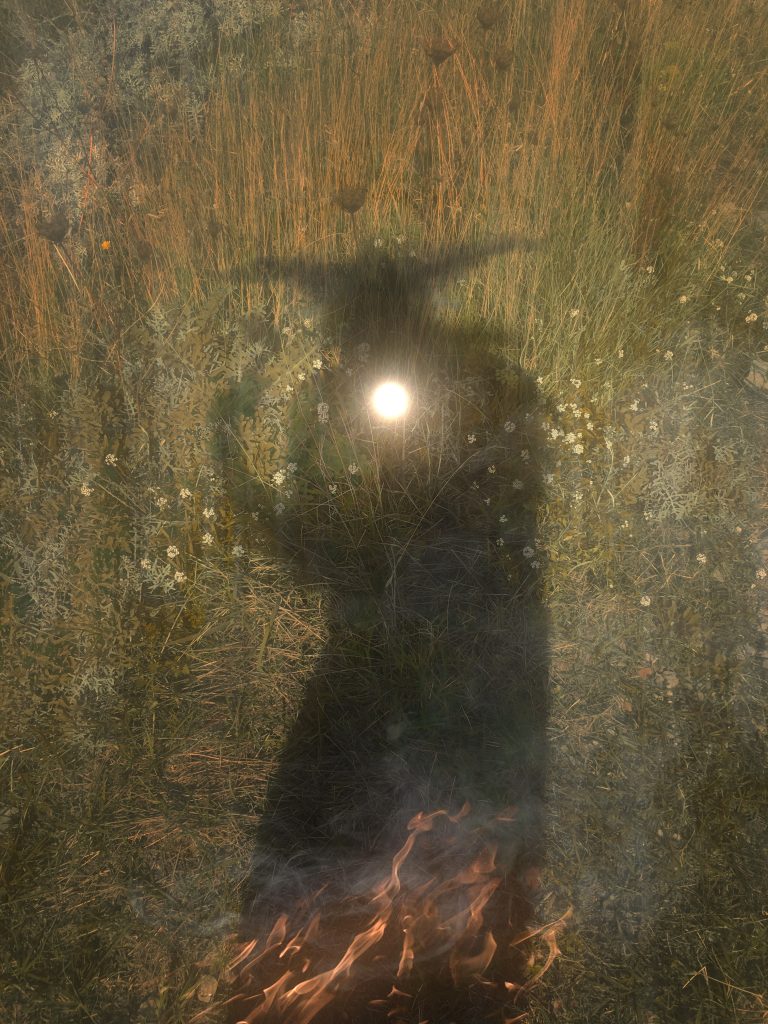

There’s a certain type of photography that I am very confident in, but I’ve worked on a few things that are outside of that. I worked on a project with National Geographic on the concept of ‘Genius’ and what it means to be a genius. The story was split into three chapters, divided by Albert Einstein, Picasso and Leonardo Da Vinci. How do you make stories of these people? You can’t take photos of them, so together with my photo editor and another photographer, we worked as a team to create a narrative with these three characters. It was really challenging, but I find challenges really fun.

The photographs, as compositional and separate entities from their subjects, convey respect for the scene. The light and angles in your style express a vantage point that leaves room for clear sight and observation. For instance, the eye level of your subjects transfers between adults and children. Do you spend a large amount of time preparing for an image?

I don’t take many photos. For a project like Couchsurfing, once I had the right picture, I could leave my camera at home and not take it out with me. Once I am satisfied with the portrait, the focus is on the story. I take photos of what I want and need for the story. When I find out what the image will be, I go looking for it, and when it’s found, I’m happy. With Ameriguns, I needed six or seven hours to create the scene; every single gun has to be in the right place, I needed to sort out the lighting, and then maybe I take 50 photos but build up the picture.

How do people feel when they are placed on the scene?

It’s a bit of a surprise for them. Most of the time, they are having fun. Something weird and unusual is happening, and they feel like they are a part of it. Most of the time, people think that when you ask, ‘can I take a picture of you’ it will be a quick snap, but when they have to do it with me, it’s a completely different thing. Some people don’t care if it takes five hours because they are having fun, and they like to be included in the process; for example, while we are setting up the picture, we could be having a conversation. In the process of creating photos, many things are happening and it’s a process with people together.

You have been in more homes than, well, most people. And you are quite well travelled. Is immersing into lives and places fundamental for your current practice? How does it feel to be allowed to probe and surround yourself with varying lives?

I’ve noticed that photography now is a language that connects people from everywhere. Everybody speaks that language, and you can look at an Instagram of somebody in China, not speak Chinese but understand something about that person. When I am with my subjects, and they see the lighting and process, they are curious because they also take photos every day, but they find it interesting how a professional does it. I like to interact with people in this way because I need to keep them happy to be there, especially if the shoot takes five hours.

Do you use assistants for your projects?

90% of the time, I’m by myself. I usually have a lot of equipment with me. When I shot Ameriguns, I had an assistant with me for 50% of the project, and he came with me for 20 days. We shared ideas sometimes on scenes and compositions, and I liked having somebody that was a part of my life already. In that case, it was because the scenes were very big. It wasn’t like Home Pharma, where everything was on the table, and I could do everything by myself.

Does this change with commercial jobs?

With commercial jobs, I always have one or two assistants, and on most of these jobs, there are quite a few people on set. It’s fun, but when you work on a set like that, 90% of the people are people you only just met. Even if I’m good at communicating with people, sometimes it’s not the same for others, and sometimes I have to work with people I don’t know for a few days, which is not as natural for me. But it’s part of the job.

Do the impact of your photographs tend to raise a level of controversy? The Balenciaga scandal looks to have been clarified, and you are now finally absolved from culpability. How does that feel?

It’s a sad story. It was the first time I made a campaign for a fashion brand, and it went so poorly. I was accused of being a paedophile for over two weeks everywhere in the world. They didn’t do anything to protect me, but now a few things are happening; I’m working with some of the media and talking to Balenciaga. I was trapped in something that was not my fault: I was there as a photographer. What they did with the second campaign (with the Supreme Court documents and books) was pretty weird, but a lot of people think I was the mind behind that too. I was not even there. For the first shoot, I was there for two days to take six photos of kids and objects; two of these objects were teddy bear bags. I don’t work in fashion, so when they gave me these bags, I thought they were ugly, ugly like punks. I didn’t see anything weird, but what happened later was incredible: I received over 5000 death threats and people calling me in the middle of the night. I was getting covered by shit, and nobody said a word about it. Now, it’s flipping over and is going in the other direction. I got a lot of positive attention from the major media, with interviews about it and people approaching me about documentaries discussing what happened. But it’s flipping to the other side.

When it comes to the media and the public, it is quite interesting how even the credits on a shoot can scale a misleading representation of what a photographer’s role is.

The problem was that they wanted my style of photo for the campaign. Children and toys and children with objects are something I have been shooting for 15 years, so it’s something that is clearly me. So with that vision, it is a lot more ‘me’ than Balenciaga in the eyes of the public. So, when the scandal came out, I think people needed to find somebody to blame, and since these photos are so close to what I have been doing for 15 years, they thought it was my mind behind the bags. When people had these reactions, Balenciaga erased everything from Instagram and the website and then published another campaign made together with Adidas, which was even worse because it felt like it somehow confirmed that there was a message behind these campaigns. It was unfortunate because everybody thought it was me behind the documents and both campaigns, even if I didn’t decide on a single detail about that campaign and was only at the first shoot.

How does a commercial shoot run? Did the Balenciaga set involve you being the only one controlling the image?

I was there with 25 other people around me, including the parents of the kids. Everybody was having fun and was there. I thought, OK, I trust these people, so I’ll take the picture. I didn’t see anything weird going on, and I can’t decide to take a photo of something just because I think it was ugly. I was already in Paris, and I already signed the contract. They said, ‘I want you to make the same style of photo for us but with kids and our collection’, so I said yes, because I knew they had bags and sunglasses and it was a commercial. So the first time I saw the collection was after I signed the contract and went to Paris. I had never seen it before, so I was there and saw these punky bags and everything else and the 25 people around me, and if they say the set is OK, then I trust these people and take the picture. I didn’t see anything weird. When something like that is put in front of you, you think, ew, this is ugly. But that’s it. It just looks like a little monster. My nephew is seven or eight years old and plays with monsters, and they are super ugly, but if I put that monster together with Balenciaga’s bags, they would look alike.

How do you feel about the idea of cancel culture and people being influenced by mass media?

The media played a big role because many major media sources created stories that were a lot bigger than what it was, and they triggered an atomic bomb. Balenciaga made a huge mistake, especially with how they handled the whole thing. It was weird because they sued a company, then the set designer, and then admitted it was wrong, and they wouldn’t be suing anyone. Even the communication with the scandal was weird, they stopped communicating with me during these days, and I was trying to reach them as I was getting death threats and wanted them to do something. Anyway, it was a sad story, but it’s luckily over at the moment.