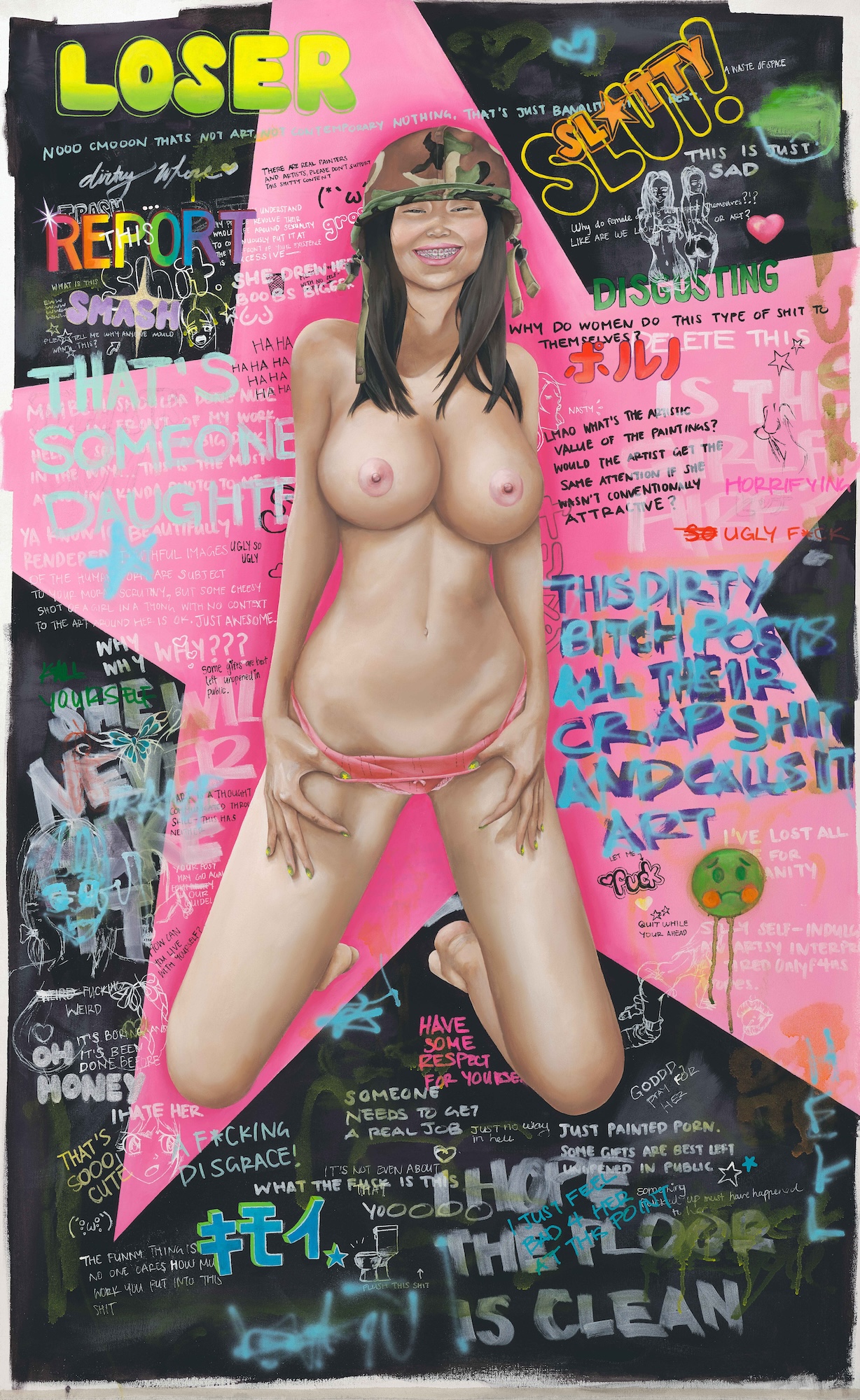

21st-Century Boy Band

“Maybe this is the begging of a chapter of hope” says Ville Haimala who, alongside Martti Kalliala, makes Amnesia Scanner. For the past few years they’ve been collaborating with French artist Freeka Tet on live streams, live performances, singles and now an LP. Their latest offering, STROBE.RIP, is a kind of snapshot into what could be a new era for the group.

In our zoom conversation, an internet lag causes their voices to converge in a surreal harmony that oscillates between temporal delays and shared laughter. But they don’t let it deter them. To Amnesia Scanner & Freeka Tet, technology is a tool to be tinkered with, deconstructed and recalibrated to create familiar yet uncanny results. There’s always a twist. Their live shows plunge audiences into smoke, sound and light, forcing them to partake in a ‘roided up sensory experience that fuses observer and participant.

The Amnesia Scanner project began online as cryptic videos and enigmatic songs sung by ‘oracle’ and produced by the ‘xperienz designers’. Now after almost a decade of building their labyrinth they’re knocking down the walls to reveal a harmonious exchange of ideas where even the crustiest sample plays a part in their audiovisual puzzle. The frictions of their past LPs have given way to something more rounded and smooth. The angst has been quelled and the group even go so far to envision a whimsical future as K-pop style idols.

Raudie McLeod: For most people Amnesia Scanner & Freeka Tet exist online through special URLs, streaming platforms, discord, even a local WiFi network etc. Where are you IRL?

Martti Kalliala: Right now I’m in Berlin.

Ville Haimala: I’m in eastern Finland.

Freeka Tet: I’m in New York.

Raudie McLeod: You’ve recently played live shows in various cities around Europe and also two shows in Australia. How do you collaborate and practise when you’re in different time zones?

(The zoom called lags and FT, MK & VH all speak in unison, stop in unison, and then chuckle in unison)

Ville Haimala: This is how we collaborate… with a huge lag! Since the beginning Amnesia Scanner has never worked so much based on a traditional band or studio session format. It was a distributed project since the beginning and we’ve always worked with different people in different places. It’s quite an online native thing. I guess this is the way we also build our live shows. A lot of the work is done online before and then we convene and start putting pieces together.

Martti Kalliala: I can confirm that. There is a group chat. There’s several group chats actually, with different collaborators and a lot of this happens asynchronously.

Ville Haimala: and a lot of chaotic folder structures of different medias.

Freeka Tet: Time for a little sponsorship with dropbox, I think….

Raudie McLeod: STROBE.RIP is a fairly stripped back version of your previous albums. It sounds as though Amnesia Scanner have been softened by the trauma of reality post-covid and the present living crisis. It’s an emo album in a way. Did you approach the songwriting differently?

Ville Haimala: Somewhat yes and somewhat no. I don’t think the songwriting approach is different other than working on some of the material together with Freeka. Songwriting for me is more like channeling. it’s not so much deciding ‘I’m going to make a song like this or I’m going to make a song like that’ it’s more so working on material and seeing where it ends up and I guess in that sense something has become more emo or more mellow. Or maybe the two previous records were so angry or loud and it felt good to have a bit of an oasis. I think STROBE.RIP is at the same time very soft but also very intense. There are sides to it. ‘Merge’ is probably the most distorted and loud song we ever made.

Freeka Tet: When we started to do music together during covid, way before the album, it was more band oriented. We spoke a lot about our beginnings when we all teenagers and started to do music. We were all in bands when we were kids. The emo came from that, the common ground of us as teenagers, so maybe it’s stuck a little bit.

Ville Haimala: Our first ever musical collaboration was a streamed performance that we did over 3 days where we arranged some of tearless and some unreleased material into literally unplugged versions and streamed them over this campfire setting. The seed for this collaboration was sown around that time.

Raudie McLeod: I’d been an amnesia scanner listener for some time, but my first introduction to Freeka Tet was the Unplugged: Part 5 performance at Terraforma 2022. The long prosthetic arm was spellbinding. You have a knack for mangling the expected, for example your piano keyboard software. How did you arrive at this point in your work?

Freeka Tet: The prosthetic animatronics is something in common with Amnesia Scanner. This absurd, almost dadaist vibe that I grew up with. I grew up watching Cunningham and Gondry. All that stuff, all the weirdness, I always liked it. As for the piano, my work in general is more performance based. I’m not a musician per se, as in writing music. I think I have always been really into making music with daily activities. My main performance before Amnesia Scanner was making music just with my face. I needed something very universal that I could play in Japan or Berlin or wherever and the reading would be the exact same. Very universal. The piano thing, there’s a performance I started to work on where I was thinking ‘I just wanna do music based on me reading and answering my emails’. They’re very mundane tasks but they could have a musical output. As for the prosthetic, I began to work with masks and stuff like that because making them is super interesting to me, the process is cool. When Amnesia Scanner asked me to join them for this performance I thought of what I could provide them. I thought back to this performance I used to do with a microphone and a remote to control my voice and the long arm was a way to hide this weird object. Also it’s a pretty iconic shadow to have a very long arm. It’s pretty easy to spot from afar.

Raudie McLeod: Your immersive live shows employ playful twists of the status quo, for example, Freeka’s microphone has a spotlight which points at the audience instead of the performer. The large screens feature fragmented text prompts and text-to-image jpegs. In the dark rooms where you perform I’m struck by the similar feeling to scrolling my phone in bed, illuminated by the screen, being presented whatever the algorithms decides. What are your thoughts on transforming viewers into participants?

Martti Kalliala: we’ve always been very interested in taking the basic elements of a live performance, the visuals, the effects, and using them to the maximum or to the extreme. We force the audience to participate. You’re enveloped in smoke and it’s hard to orient, or you’re bombarded with strobes which have this hallucinagenic effect. In a sense we, I don’t want to say abuse the audience, but you almost have no choice.

Ville Haimala: It also seems like the music performance culture has this big pressure to be immersive and it’s fun to put it on steroids. To tweak the intensity so high that it’s like ‘Now you have the spotlight in your eyes. Now you have this bombardment of things.’

Martti Kalliala: Amnesia Scanner started as this very online thing in the sense that we weren’t associated with it. The music only existed online. We thought it was very interesting to make the live counterpart as visceral and engaging as possible by pushing the physical impact of it to some kind of extreme. Now in some sense the live show has almost become the main medium of the project. All these different elements come together and it definitely has some primacy in our heads as the main output.

Freeka Tet: For the live shows, we’re trying to accentuate a band-feeling or a human-side of things, but when Amnesia Scanner is on stage, they have never really been in your face as people. The spotlight is pretty representative of what’s happening. It shines on the audiences’ face, and you can’t see our face. It’s not really clear what’s going on. On the other side, because it’s something that is mobile, the movement translates the human. It’s not a machine doing it. It becomes more organic, but it still anonymous. It prevents us from presenting our face.

Raudie McLeod: One of the comments in the ride film clip reads “finally, something to wake up to.” How do you feel that your new album together is giving people some reason to live in this confused post-modern society?

(silence for 5 seconds, then laughter)

Freeka Tet: We laugh about it. And all the different types of laughs you can have, the real ones, the weirder ones…

Ville Haimala: Since the previous two albums we’ve been going through some stages. There was anger, there was grief. Maybe this is the beginning of a chapter of hope.

Raudie McLeod: I read in previous interviews that creating your own music is about collecting all the sonic crumbs and making something unique from them, that your production process is kind of a secret. Is there anything you’d like to reveal about your process now that it sounds like it has changed somewhat?

Ville Haimala: It’s not that there’s some sort of secret formula. We have our ways of pushing different material through our processes and with the sausage at the other end we try to formulate something. We create sound as raw material and then sculpt something out of that. It’s always remained the same since the early days when the work was maybe a bit more collagey or less structured but I think it’s still in it’s core the same process. Now there’s maybe more of a songwriting angle to it but that’s been present since quite a long time. I personally feel it’s a natural continuum of things. As time goes by you find new tools and new ideas, but the basic process is still quite the same. There’s no secret sauce. It’s just our exchange and us bringing these different pieces to the table and planning something together.

Martti Kalliala: All sound is equal in the process. Some crusty sample can play a part. Maybe it’s not 100% true but it’s mostly true since the beginning. In the beginning we were sampling stuff from surprising sources. I think now it’s very common. This non-hierarchy of sound is somehow the thing that has remained.

Freeka Tet: The process is quite versatile. Sometimes a song can be really concept driven, based on the way the world around the music has been built, sometimes the music comes on its own and builds the world. It’s an eternal feedback loop. Sometimes a concept before can become music and sometimes existing music can bring more detail to the overall concept.

Ville Haimala: And that applies a lot to the project. On this album we’re working again with Jaakko Pallasvuo writing texts for us. We’ve been working together since the beginning of the project, almost 10 years. Instead of him writing particular lyrics for songs, he gave us a bunch of texts that ended up being the inspiration for a lot of visual and sonic stuff. The same with PWR studio who create a lot of our visual language, the briefs are never very clear, in that we wouldn’t go to Freeka and say ‘Hey can you build us this, or hey we need this visual’. This is maybe why the whole world can feel a bit random or incoherent at times, but that’s all really fun. A lot of stuff ends up being used in a very different way than it was intended. It’s an open project. I feel that it must be an interesting project to collaborate on contribute to because the end result is fairly open ended.

Freeka Tet: As a collaborator the way I would see it is this. Imagine walking into a teenager’s room. There’s a lot of elements. There’s visuals, there’s posters, there’s music playing. There’s a world they’ve been building. This is what Amnesia Scanner has been doing for a decade almost. You are free to look at it, take from it what you want and add to it what you want. That’s pretty much how it works. There’s a lot of freedom but the environment is set so you can’t be fully outside of it. There is already a direction.

Raudie McLeod: Back to the Ride film clip. What’s wrapped inside the black packages?

Freeka Tet: This is based on something Amnesia Scanner already did. When I started to work with them they had a lot of collaborators and a lot of details. I’m very detail oriented and there is one video they already did a long time ago which was just someone unwrapping objects and this stuck in my head. I like repurposing old stuff. I’m a big recycling guy.

Ville Haimala: Yeah it was the AS Truth mixtape video.

Raudie McLeod: I read a comment on the AS Truth video that said something like ‘this is what’s inside the ride packages’

Freeka Tet: Well I guess we will never really know what’s inside the package…

Raudie McLeod: STROBE.RIP might be the first album that lives entirely in the 21st century. Your press release states “amnesia scanner is now living in the world it built.” This world seems to possess a strange logic which sits at the limit of information and comprehension. My question is what comes next?

Ville Haimala: We have some ideas of where it’s going. Building this story with Freeka is definitely not over, there’s already quite a lot in the pipeline. As it’s been communicated somewhat, STROBE.RIP is a piece of a bigger puzzle which involves us doing a lot more performance work. We mentioned already the live streams. There are different formats which extend the project. There’s many directions.

Martti Kalliala: Referring to the cycle of work that STROBE.RIP is part of, it’s unclear how it will end or how long it will go on.

Freeka Tet: Because we’ve been working together with the live before we recorded any music, one of the conceptual directions we had with this album was that usually you release music and then go on tour to defend it, where here we were interested in, not so much releasing the music at first and touring but building music through the live performances. One big difference was that most of the songs were sketched as band songs first. We thought instead of sampling bands, let’s build a band for each song and then sample it. The raw material was made-up bands. This could be maybe a direction… What those made-up bands were before.

Ville Haimala: The first performance we did with this material sounded like what ended up being the samples for the album. It ends up feed backing into itself over and over again. We would love to retain some kind of freedom to continue developing the material on this album or somehow and not decide on definitive versions of things.

Martti Kalliala: One of these end games that I’ve thought about is that we might start an idol franchise. Amnesia Scanner might transform into some kind of idol operation. there will be more information later.

Freeka Tet: Franchising.

Raudie McLeod: Like how Daft Punk license their helmets to imitators around the world?

Martti Kalliala: Yeah or more like a K-pop style idol thing.

Ville Haimala: We’ve had this long running joke but also a real fantasy of having a Las Vegas style show where we could get a hold of infrastructure and do a show that runs at the same venue for a season. Maybe now that this dome has opened in Las Vegas it seems like the fitting screen for an Amnesia Scanner performance.

Freeka Tet: We could be opening for Chris Angel.

Ville Haimala: Me and Martti are Penn and Teller and you’re Chris Angel.

Team

Photography · Kristina Nagel

Special thanks to Modern Matters