Practicing Reality

I met Yuri on a warm morning of July in Milan, the city where we both live.

The original idea was to interview him with specific questions concerning his works, but it quickly became clear that our conversation would span way beyond the question-answer dynamic.

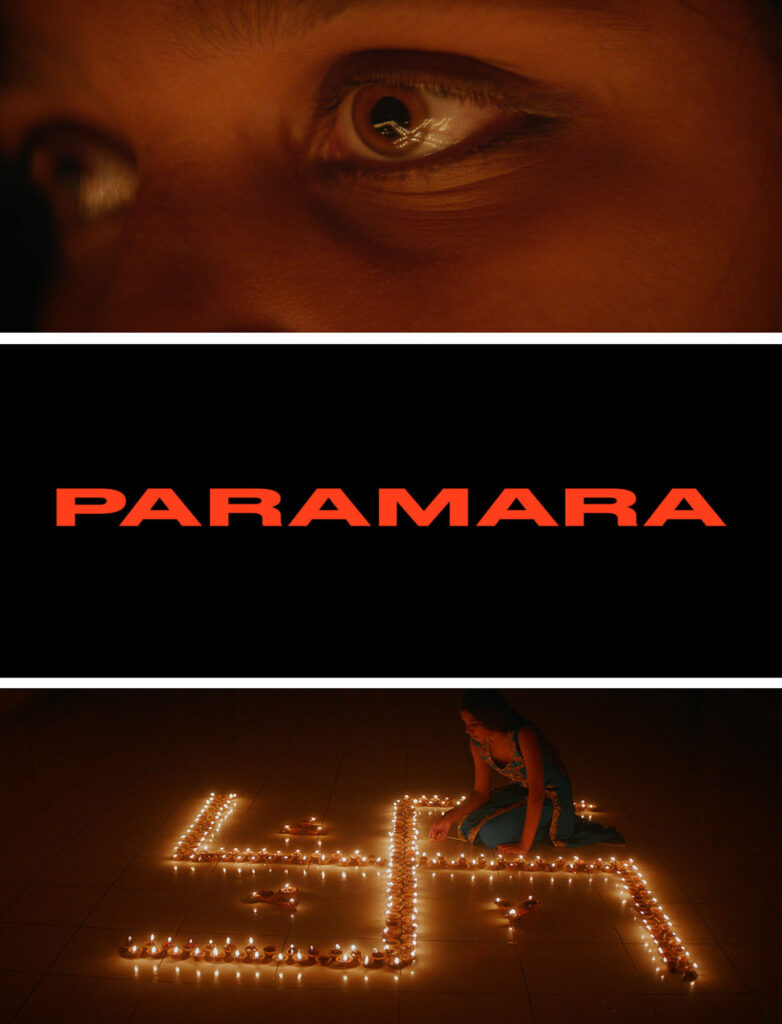

Unpacking his extensive body of work means tackling a plethora of themes: from the idea of reality and imagination to the concept of truth, from language, symbols and the importance of sound to the overall theorization on aesthetics and the genre of the documentary. The core of his works lies, I believe, in his idea of reality, and the consequences that this vision entails.

In each of his films, from the oldest series Memories for Moderns (2000-2009) to his most recent work Atlantide (2021) Yuri’s depiction of the here and now is so dense in its realness that it manages to transform into its opposite: imagination.

Quoting one of his key inspirational filmmakers, Dario Argento, Yuri says that reality is the true source of horror. The horrific aspect of the everyday is, however, not always sinister. The extreme simplicity of things, the daily life of the portrayed subjects, can be felt as scary if seen from the outside, but there is also an element of fascination, a strange allure to it.

Moreover, instead of inserting imaginative elements from the outside, Yuri portrays things as they are, showing how it is precisely the ordinary that allows the otherness of things to emerge. Reality in itself is framed as intrinsically imbued with possibility: everyday working environments, with their specific set of rules and vocabulary, contain a certain mystery, a subtle touch of magic, which does not come from the outside but from WITHIN.

The usual unfolding of regular practices, such as managing a marble quarry (Il Capo, 2010), the functioning of an hyperbaric room in an underwater station (Piattaforma Luna, 2011) or performative actions in a medical setting (Da Vinci, 2012) is filmed in its naked truth, each environment characterized by its specific language. The vocabulary varies, sometimes it’s gestures, sometimes it’s a list of orders, sometimes it’s silence.

The construction of a world of symbols within the realm of the familiar is what generates this switch: a normal setting becomes fascinating, mysterious, not fully graspable. This lingering feeling is strengthened by the employment of close ups and camera shots that are carefully edited, delivering a strange dichotomy between the closeness of the subjects, whose gestures are filmed in detail, and the detachment of the viewer’s gaze, who observes as an outsider. Intimacy is suggested and denied at the same time.

In this context music and sound play a key role, carefully studied either as translations of the epiphanic moment partially reached (see the end of Piattaforma Luna, for instance, where the composition by Ben Frost represents a moment of freedom, an escape from the almost claustrophobic reality of the hyperbaric room), or as a suggestion, like the ironic employment of orchestra music in The Challenge (2016), hinting towards the classical pomposity of Hollywood Cinema.

Some of his films, like Whipping Zombies (2017), a documentary on a dancing ritual in the tradition of a Haitian village, are entirely without dialogues. The faithful documentation of this cultural phenomenon relies entirely on the registration of sounds and music produced by the local community. In his San Siro (2014) the stadium is filmed as a concrete entity that functions as the container of an almost mystical happening, its architecture framed in its curves and angles, inside and outside. The stadium is the protagonist, the game is never filmed. Here again the only sound is given by the footsteps and the roar of the exultant crowd, and the preparation towards the football match can be read, once more, as a ritual, punctuated by different practical steps.

This idea of rituality, seen as a constitutional element of any society and fundamental in the construction of meaning, comes back often in Yuri’s works.

Its most blatant form is seen in the short film Séance (2014) in which psychologist Albània Tomassini entertains a spiritual conversation with the deceased Carlo Mollino. Fulvio Ferrari, tenant of Casa Mollino, serves the dinner to the two guests, one visible and the other invisible. Through the voice of Tomassini Mollino speaks about the sense and the aim of his passed life, as well as the direction towards perfection. This agonized perfection is reached, in Mollino’s view, through the conjunction of idea and realization. The projectualization of a work and its actual form become one, in what is beauty and truth at once.

This precise correlation was at the core of Yuri’s working method in his latest film Atlantide. While talking about this idea of truth he told me about his choice of not using any script for Atlantide, the dialogues in the film consist of footage collected during the almost four years of research, in which Yuri followed the protagonists in their daily life around the Venetian lido.

The entire creation of the film was an ongoing process, in which also practical elements such financing was collected throughout and not entirely beforehand. This experimental approach allowed for a unique challenge, in an attempt of capturing reality ‘’as it is’’, reflecting precisely Mollino’s conception of perfection in the work of art.

After our conversation I left with different thoughts in my head and the belief that a lot had remained unsaid, but the overall feeling I keep to this day is the full comprehension of Yuri’s desire: to create a work in which truth unfolds in its totality, in a temporal frame that is both process and end. For a brief moment, entirely real.

Credits

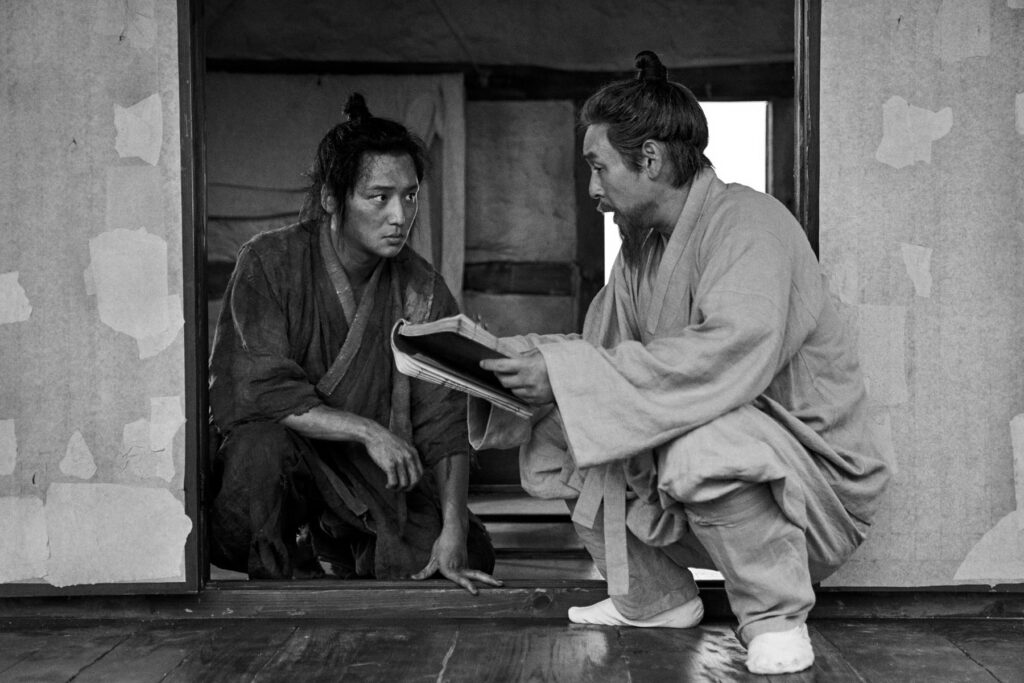

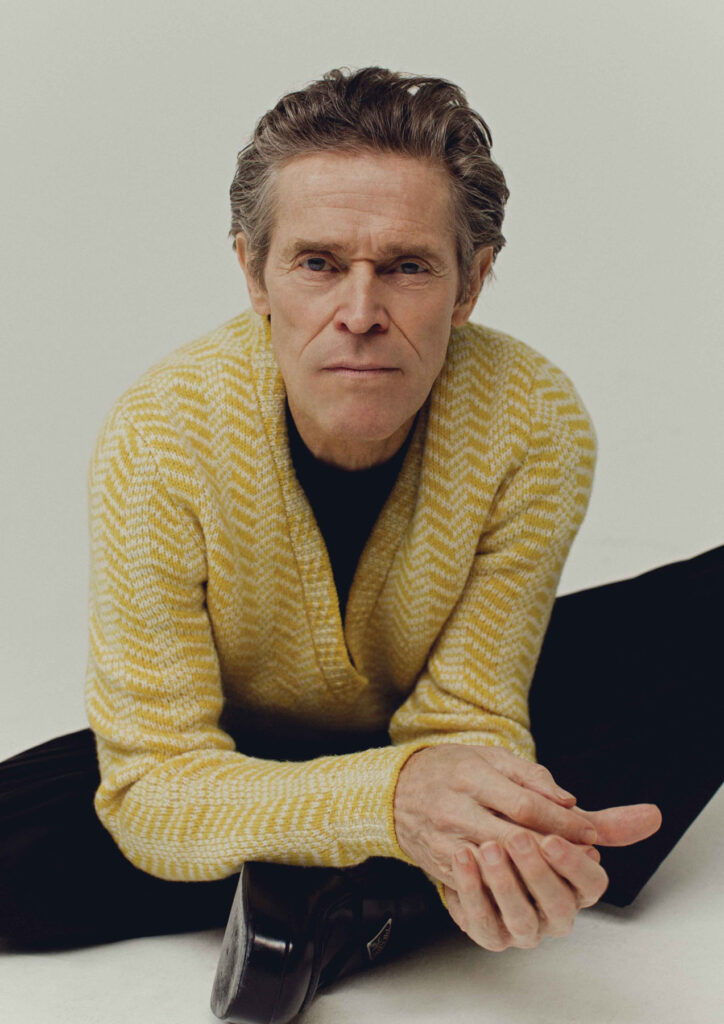

ATLANTIDE (2021) Video stills

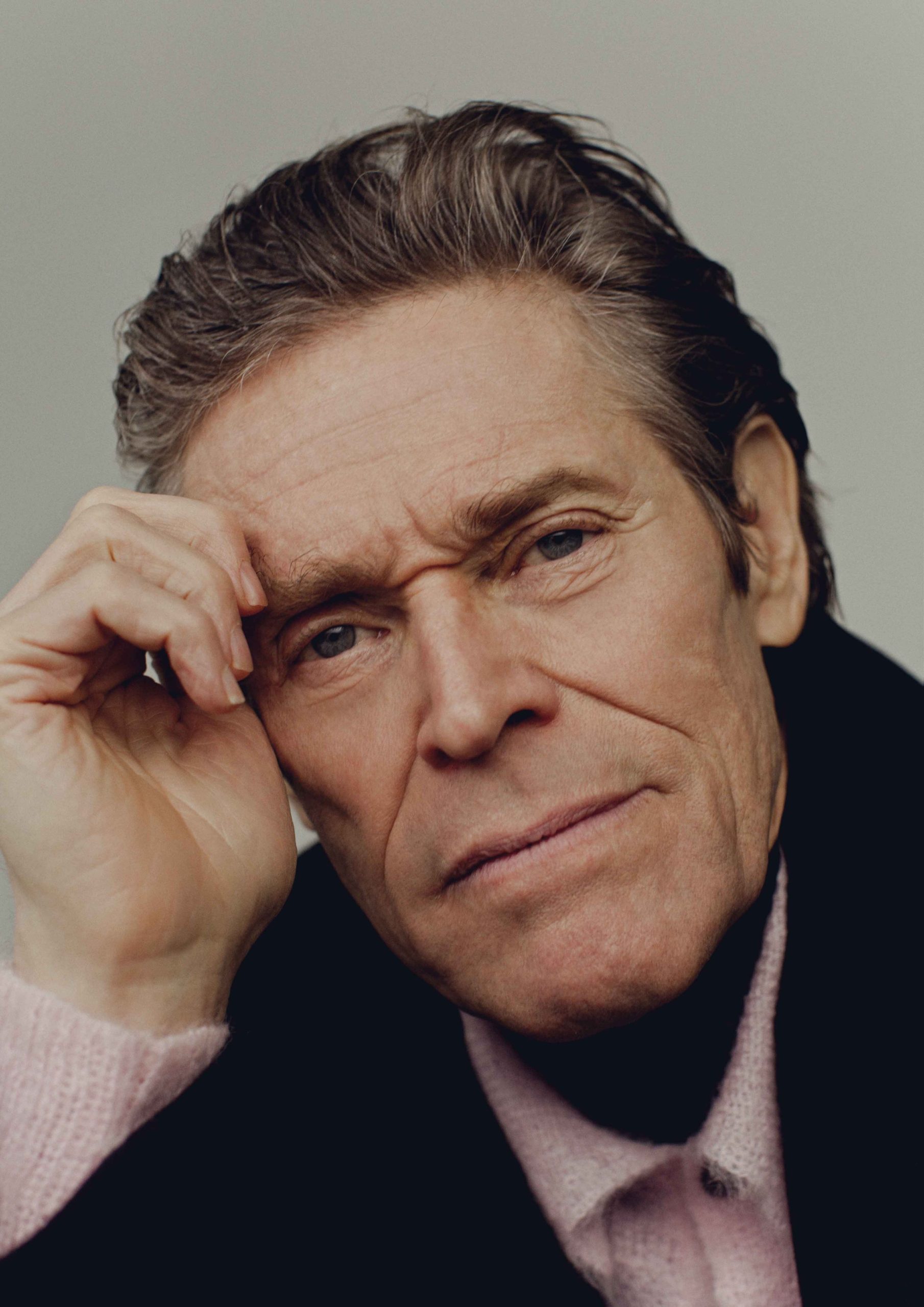

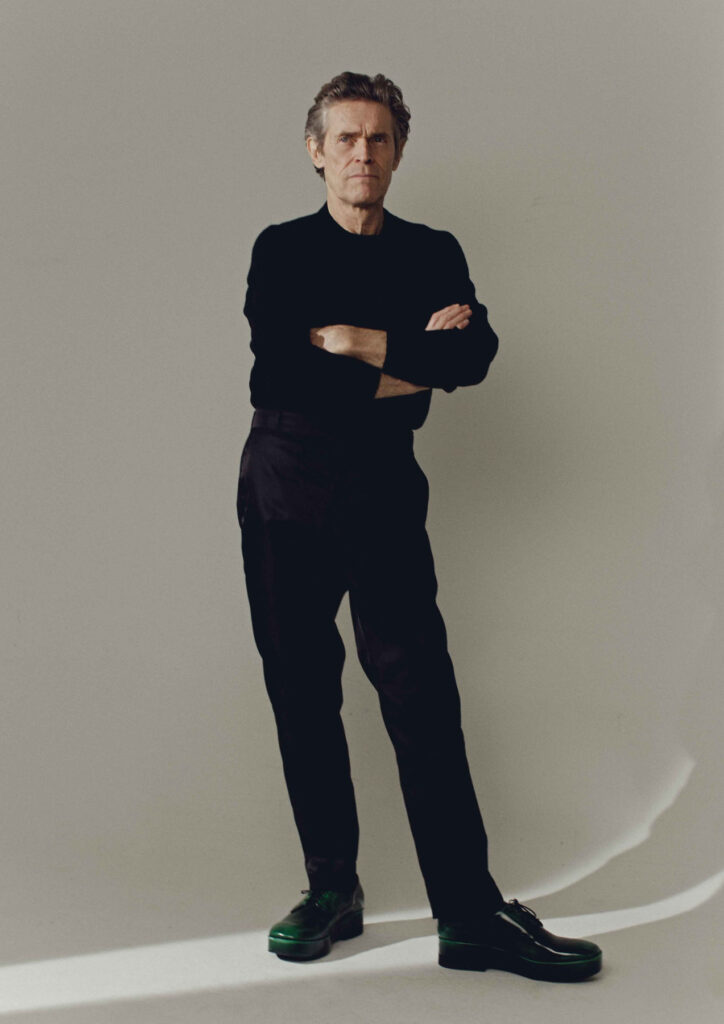

THE CHALLENGE (2016) Video stills

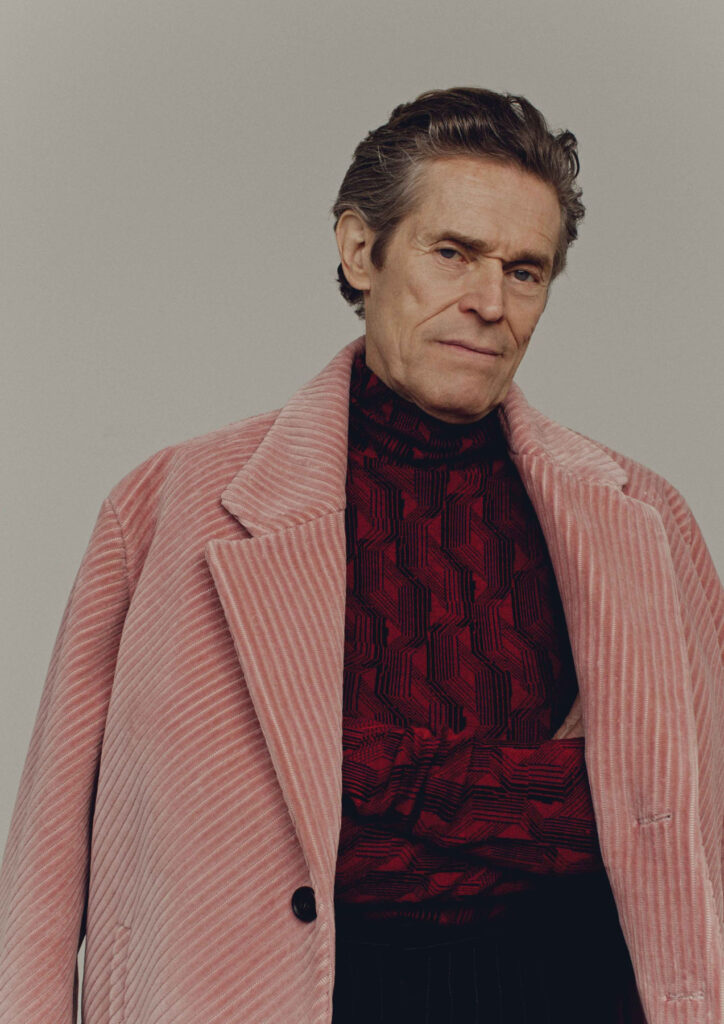

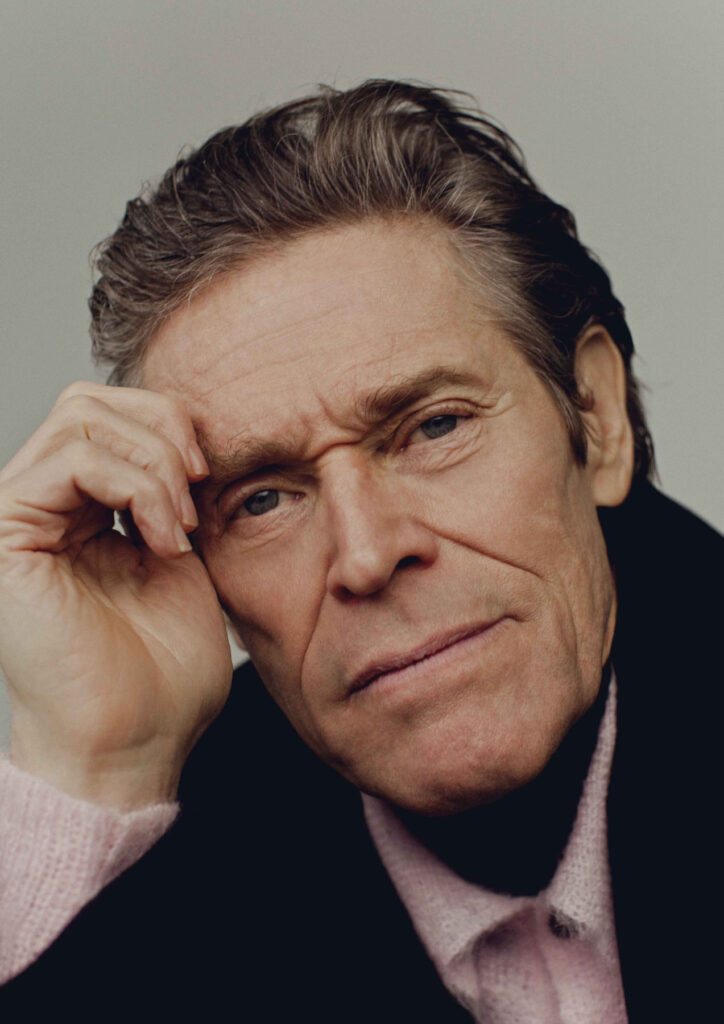

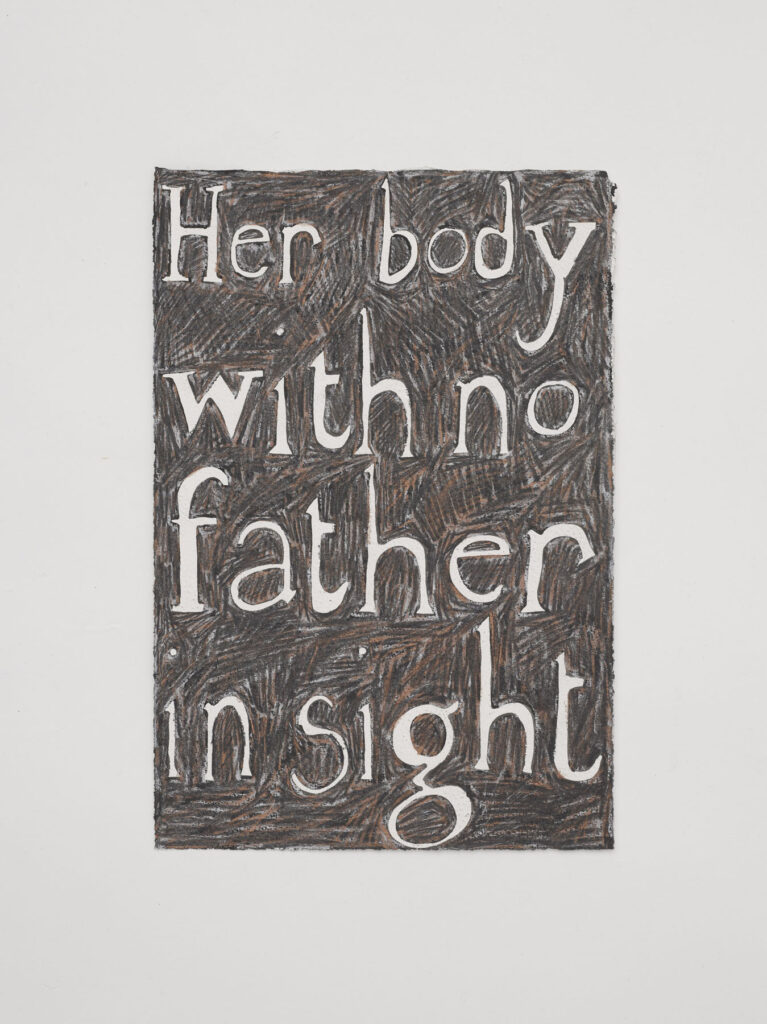

SÉANCE (2014) Video stills

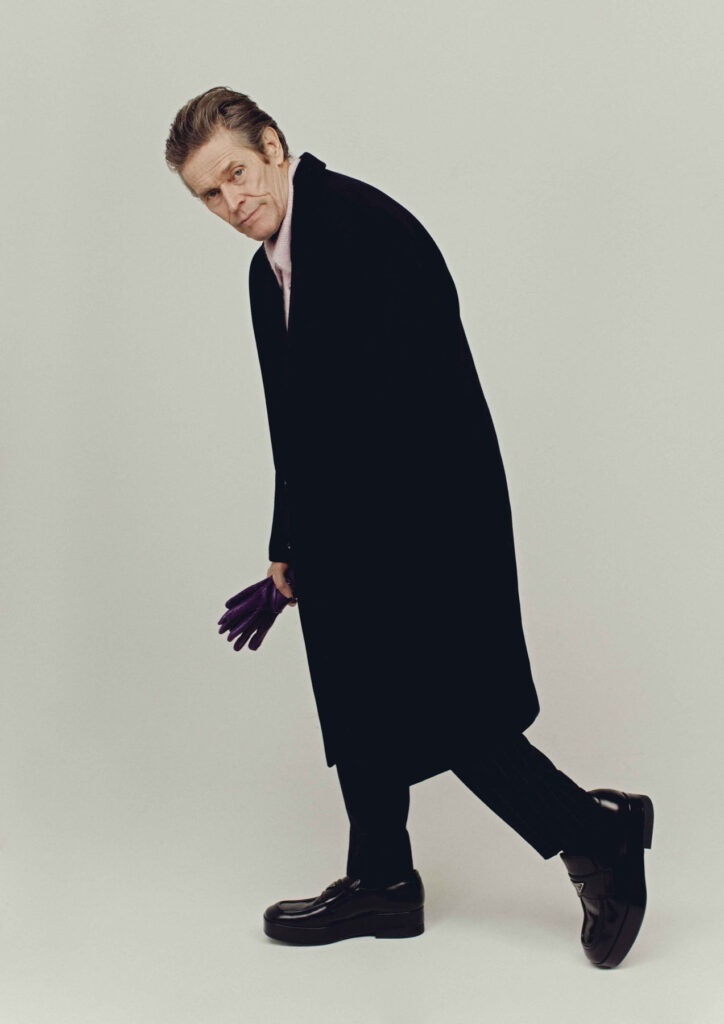

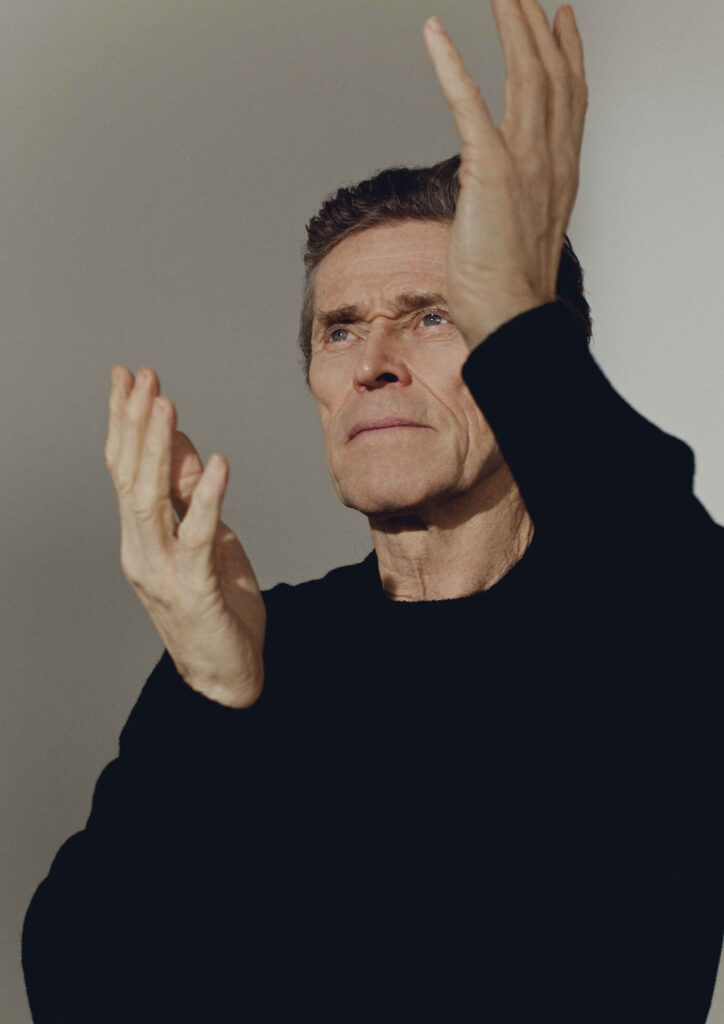

PIATTAFORMA LUNA (PLATFORM MOON) (2011) Video stills

All images courtesy of the artist.