How did the idea for Songs of Collective Isolation come to fruition, and how will this piece work in real-life settings?

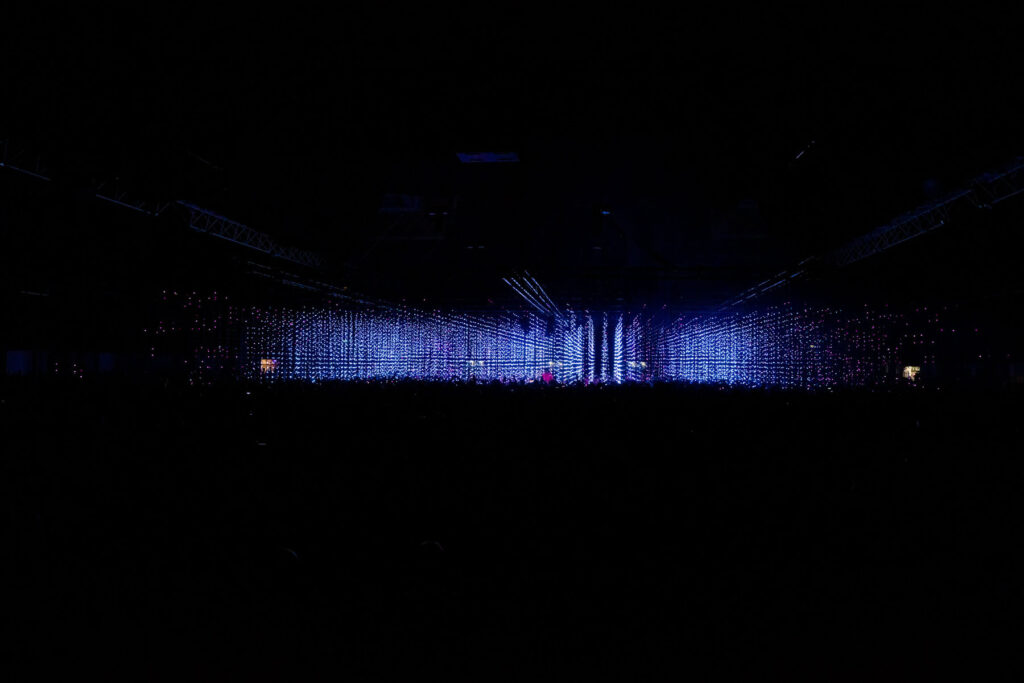

Songs for Collective Isolation emerged from a series of explorations, looking at the possibilities of minimal, slow-paced sound- and light-scapes, free from the need to think about practicalities such as people flow, visitor experience and dwell time. We wanted to create a piece that would slowly draw you in, using natural and unadorned sounds, and exploring the effects of layering multiple iterations of the same sound, each from its own speaker suspended in space. The result is a raw set of sampled sounds (a violin recorded very close up, played by Giles Francis) that gains depth and breadth when played independently through multiple speakers – it fills out; becoming an orchestra, rich and deep, from such simple beginnings. We also saw a parallel with the current global situation – social distancing, lockdowns and so on. The potential of what we can achieve together, and the fragility of isolation that we were suddenly confronted with, seem to resonate within the piece. The piece starts with a solo note that, only after quite a while, begins to build in strength and variety.

The work uses a hardware and software system we have been developing in-house for the past few years, that we call ‘AudioWave’. It is the same system that was used at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona to create a piece called Murmuration (2019-20) that comprised over 700 individual speakers and orbs of light, suggesting the movement of light and energy around the outside of that building. It builds on earlier iterations such as Wave at Salisbury Cathedral, Desert Wave at Burning Man and Canal Convergence, and Bloom, first commissioned for Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. This piece is much smaller, more intimate, with just 18 light/speaker orbs. It is designed to be seen in quiet, private or controlled spaces – again resonating with the current situation.

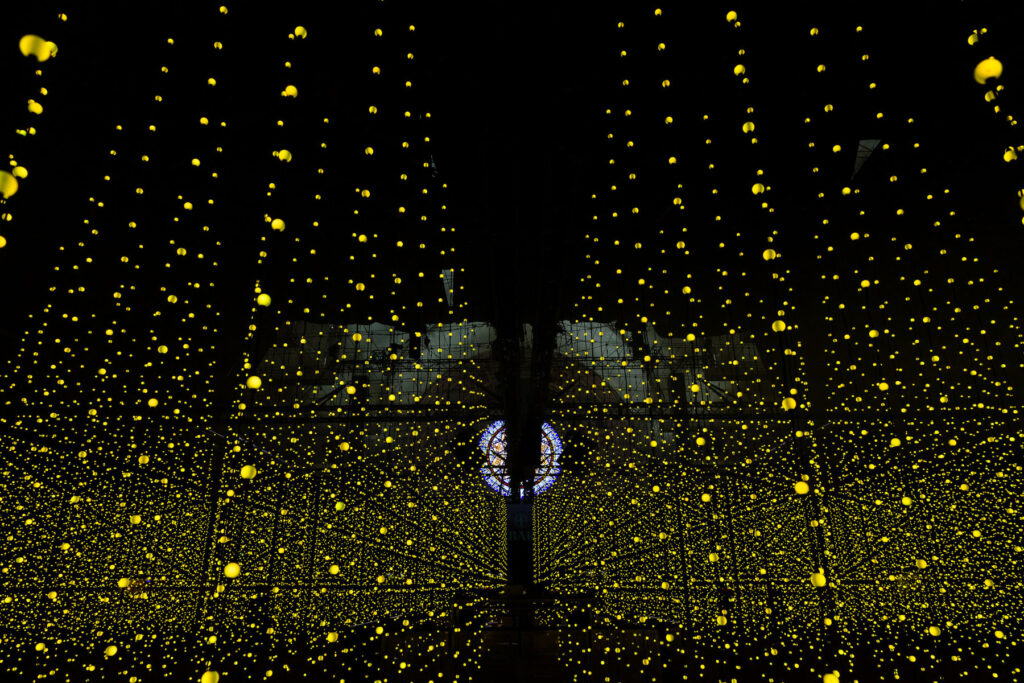

The footage of Where There is Light is poignant to watch; How was the work, with light responding to the stories of refugees and asylum seekers, developed?

From the outset our goal was to create an abstract space in which people could listen to some real stories from real people; refugees within their midst in Gloucester. It was also important, I think, that this was done in a positive way, as part of a non-lecturing experience. And finally, we wanted to bring attention to the amazing work of GARAS (Gloucester Action for Refugees and Asylum Seekers). An opportunity arose to show the work in Gloucester Cathedral, and we worked with Everyman Theatre and Music Works, two local organisations, to put the piece together.

Visually, we wanted each of the four testimonies to have a different feel, a different visual reference. And finally, there is a musical crescendo where we took the opportunity to let rip with the lights a little! The project was a collaboration with a refugee organisation local to the studio in Gloucestershire UK called GARAS. We all hear stories of refugees, but the enormity of their ordeals is so outside of our experience, that attempts to represent their lives becomes mired in the discussion of guilt, responsibility, economics and race.