“It flows, it bubbles, it can be matte, shiny, satin – it’s great”

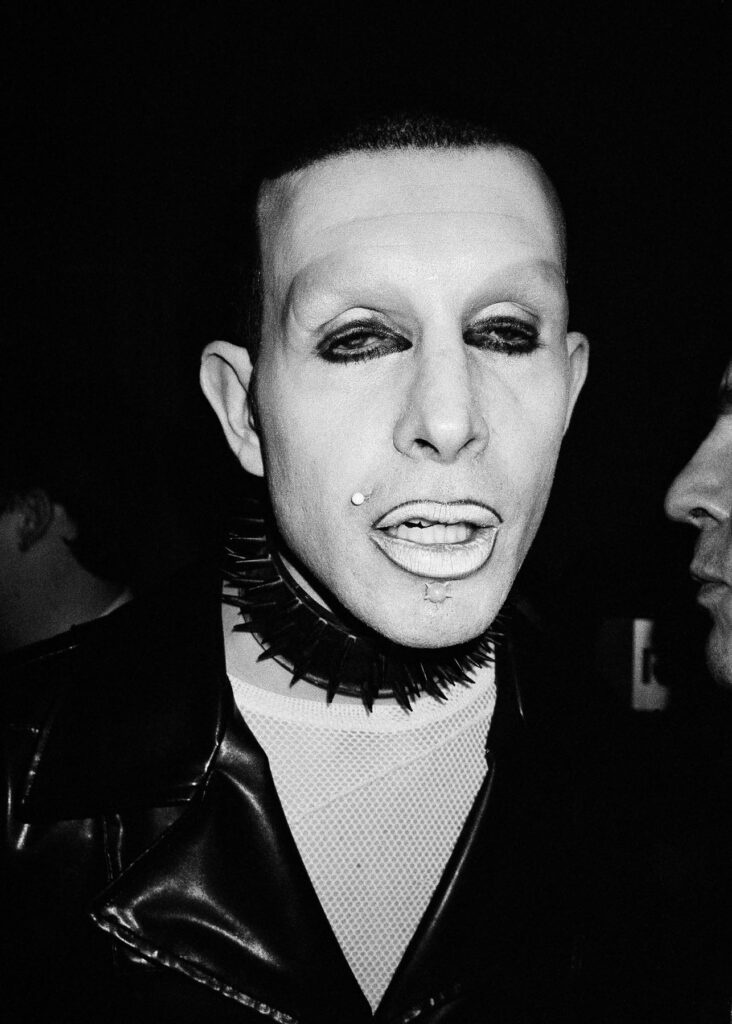

Multidisciplinary artist Naomi Gilon has a rich history of experimentation that encompasses a wide range of methods and materials. The Brussels based artist combines beauty with the macabre in a strong effort to break away from the restrains of the art world’s expectations.

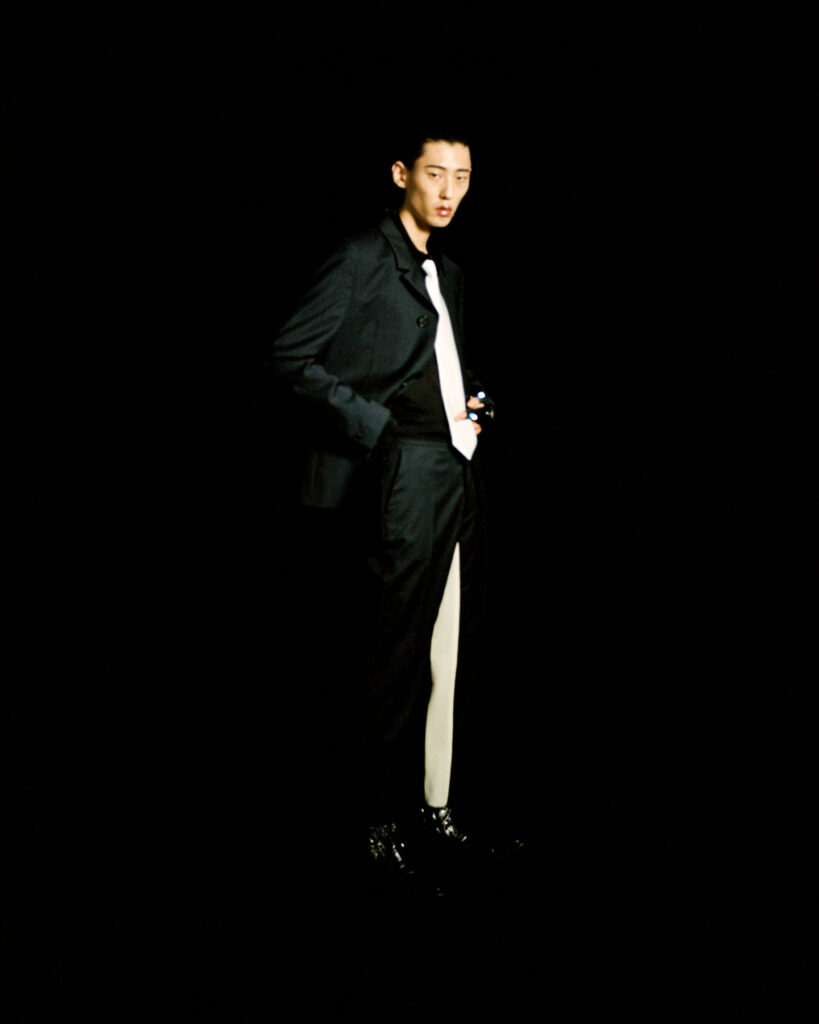

Gilon’s ceramic work has a life of its own. Consisting of a series of sculpted bags with claw handles, vases with long witchy fingers and high heels with mangled toenails, her pieces challenge our perception of the medium. Drawing on a wellspring of inspiration from pop culture, fashion, gore, and mythology, Gilon explores the aesthetic and psychological potential in everyday objects and breathes new life into them through her process of metamorphosis.

Gilon embraces the fiendish and the unconventional in her practice and crafts her pieces with a glaring sense of beauty. Her ability to transform everyday items into otherworldly hybrids subvert our attachments and relationships to the objects, forcing us to sit with and question our sense of discomfort and ultimately, our sense of being.

NR Magazine speaks with the artist to find out what makes up the weird world of Naomi Gilon, and what her monstrous creations can reveal about us all.

Does the desire for experimentation with your work stem from anywhere? Do you channel this into other aspects of your life?

It’s my way of expressing what I think. I have always been a shy child who listened to the needs of others. It’s not easy to extricate yourself from this behaviour when you become an adult. It’s both a work on myself and on others. I try to have a sociological point of view with my work. It’s a reciprocal exchange between my art and me; I bring reflections to my work through my reading for example, and conversely my works teach me a lot about life and myself. So, this desire to create and to experiment is simply a desire to live. I also channel this energy through botany. I like to see the evolution of plants.

Your practice has evolved a lot over the past few years – you’ve created installations with found objects and explored the tuning industry, whereas now, your practice has moved towards ceramics and crafting objects from scratch. Can you talk about this development?

It’s true that the discovery of ceramics was a revelation for me. Before that I worked mainly from assembly methods, textiles, car body parts, stickers, etc. The hybridization process was already present. As a self-taught ceramicist I’m able to not be in a system of appropriation of forms, but creations. I have almost total control over the objects I create.

Also, my subjects contrast to the ceramic material: fragility and violence, the sublime and the monstrous. I like it a lot because we are looking for confrontation. Beyond that, my thinking remains the same, over time I’ve just deepened it. It draws its source from popular culture. It’s a very large and constantly evolving subject.

Is constant artistic evolution important to you?

Yes of course, it’s linked to our personal development. As I mentioned before with experimentation, the evolution of our work is needed to live.

You’ve exhibited your work in lots of places in Europe. What is most important to you when displaying and showcasing your pieces?

What is most important to me is sharing a story, first and foremost a fantastic story and something that makes you dream. We try to widen the boundaries of the mind and share it with as many people as possible.

I also realise that my works have their own existence. Once out of my imagination, they travel without me. We see them for what they are, and I become secondary, as sometimes I answer questions for interviews. What I mean is that my works don’t need my words to create a discussion with the person who encounters them.

Throughout the development of your practice, I’ve noticed that your sculpted claws have remained present in most of your pieces and have become a sort of key signifier for your work. Could you talk a bit about this recurrent motif? What is the narrative behind it?

The claws appeared to me through the imagery of car tuning – the beast under the hood, the roar of the engine, etc. Then at the same time I discovered the book ‘Crash’ by J. G. Ballard, the film ‘Christine’ by John Carpenter, and the film ‘Titanium’ by director Julia Ducournau.

Following this car-related imagery, I plunged into the world of gore and horror films. They’re an inexhaustible source for questioning the identity of a monster. I also turned to mythology, folktales, Nordic stories, etc, as well as representations of the figure of the monster in paintings through the centuries. It’s a timeless fascination.

“I consider my hybrid ceramic objects as the chimeras of our humanity. It’s the sublimation of the horror in our lives.”

Your work, and your recent ceramic pieces in particular draw on aspects of horror, gore, fashion, and pop culture. What are your specific influences and what intrigues you most about these things? Have they always been of interest to you?

The human hybrid has fascinated me since I was little. I’ve never been a big fan of monsters before; it was through my painting studies at ENSAV La Cambre in Brussels that I explored these interests.

I’m influenced by the cartoonist Emil Ferris, the authors Aldous Huxley, René Barjavel, Philip K. Dick, George Orwell and the authors of the Nouveau Roman like Alain Robbe-Grillet. Also, directors like Ridley Scott for Blade Runner 1982 (my favourite film), Dario Argento for Suspiria in 1977, Rosemary’s Baby, David Cronenberg and Videodrome…. the list goes on and on.

The image of the monster can take different forms, it adapts to the times and that is what fascinates me. It’s always a reflection of society.

What is it like living as a creative in Brussels? Has Belgian culture influenced your work at all?

Living in a large multicultural city is very rewarding, and Brussels has lots of great qualities. The arts scene is important, but I don’t draw inspiration from it directly. Everyone is obviously hugely influenced by the internet. Subliminally my influences are global.

But still, I love the work of Aline Bouvy and Xavier Mary – they marked my debut in the art world.

What was your aim when creating your online shop?

To break the notion of art acquisition. During my studies we were told that walking into an art gallery is like walking into a store. I never found it easy, and I think most art spaces want to keep that aspect of privilege. By creating an online shop, I feel like I’m breaking away from these principles. People who enjoy my work can acquire it as easily as going to collect bread in a bakery. We buy unique things in an almost banal way. And the direct creator-to-buyer relationship is easier than having one or two intermediaries, but I do enjoy collaborations and discovering new networks of people, I think that’s really important.

The form and texture of your pieces have always been interesting to me. What’s your approach to working with different materials, and are there specific materials you enjoy working with the most?

I really like materials that imitate others, like faux fur textiles or mock snakeskin, or materials that drip, or spread like a disease. I love studying the set design and makeup of 1920s gore films.

I also love having my hands in clay. It feels like a real connection to the earth. My favourite part is the last step; that of enamelling. There’re always surprises. The colours are always unique and have an almost captivating depth. It flows, it bubbles, it can be matte, shiny, satin – it’s great.

What have you been finding inspiration from at the moment?

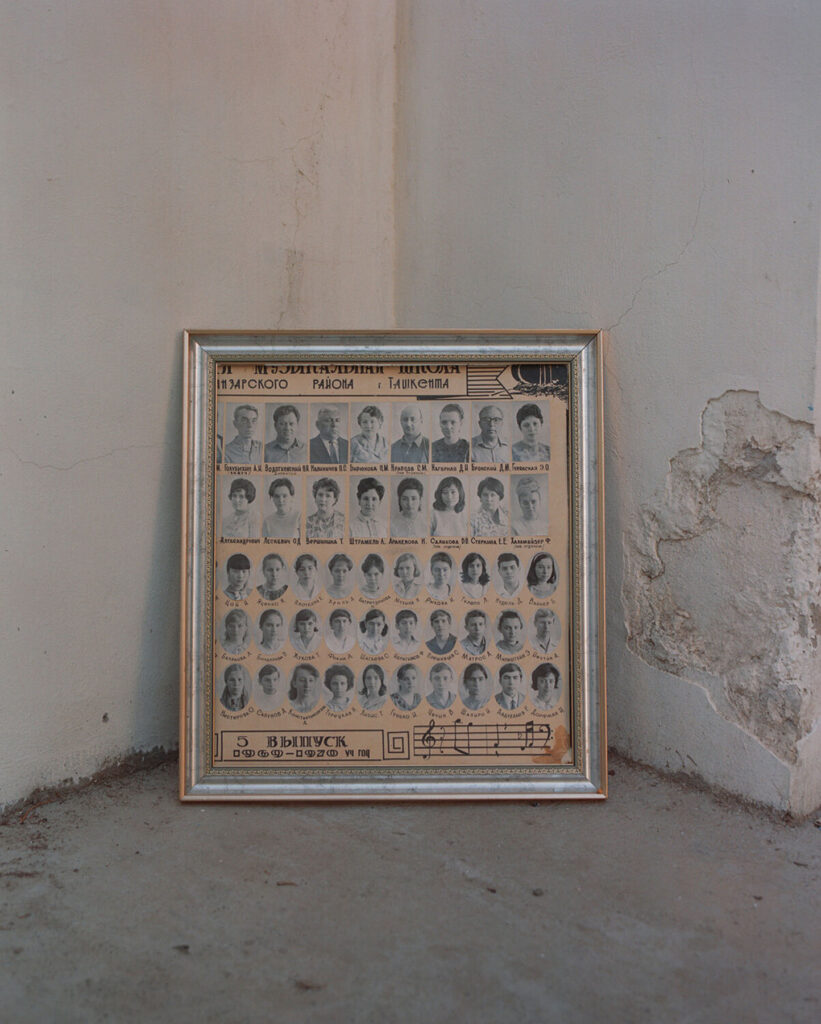

My creations of monstrous shoes were inspired by the exhibition ‘MARCHE ET DÉMARCHE’, at MAD in Paris in 2019. My interest in the historical journey of objects emerged from this exhibition. This is a process that is now part of my thinking and methodology. My new bag series is also based on a nod to the past; it’s an object with great history and connotations, that never ceases to evolve, like a living being.

You’ve mentioned that with your work you try to put societal fears and desires into narratives, words, and images. Why is this important for you, and has this always been a focus of yours?

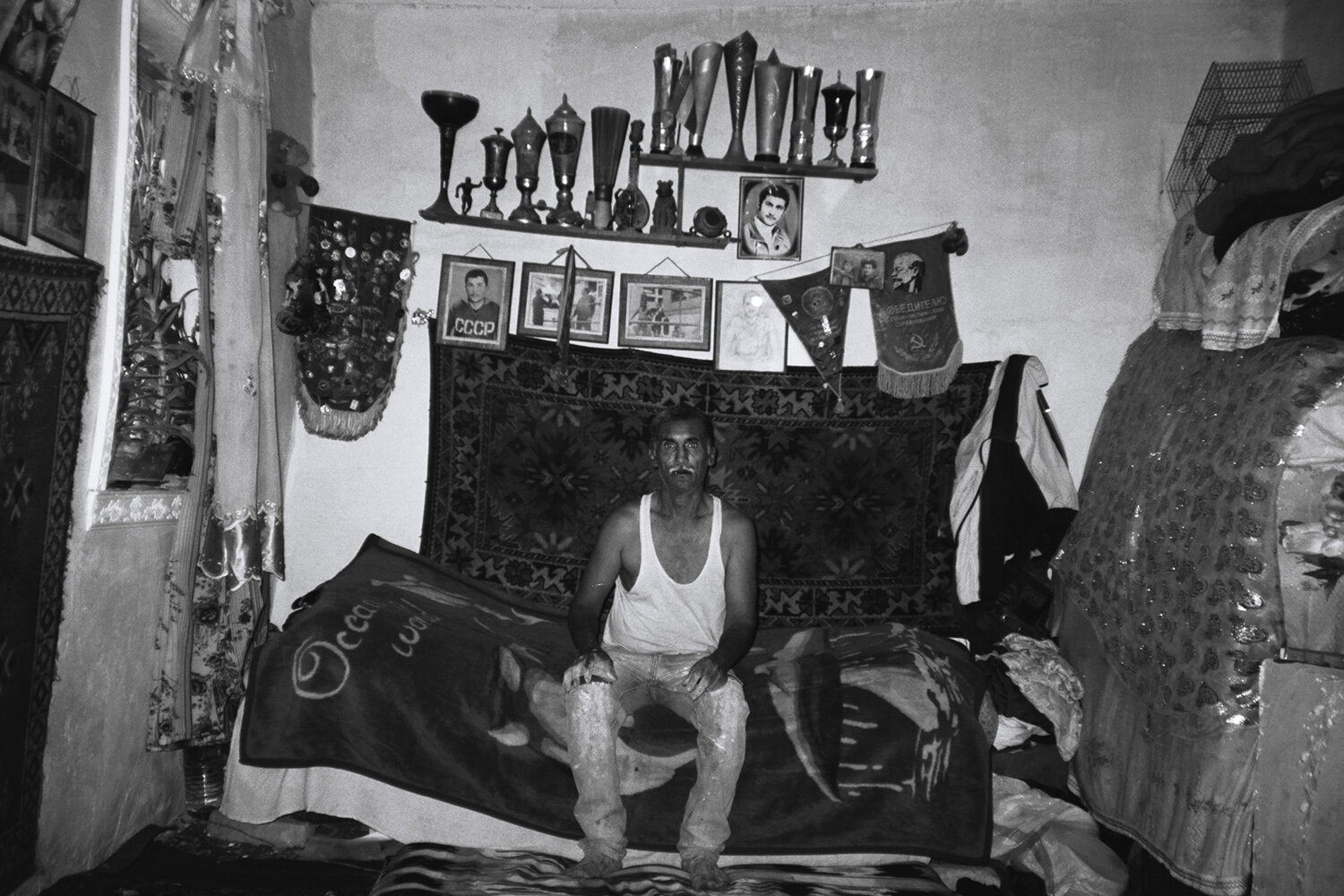

It’s a way of making memory appear physical, and to create memories of objects. When I started out as an artist, the term ‘connotation’ was a big part of my way of thinking. The spare parts of cars whose sheets were crumpled, bent, and scratched were the vestiges of a moment in time and of an emotion.

The concept of time is very important to me because it moves so fast and takes with it the things that have forged us like words, objects, smells and people. When I make a piece of ceramic, it’s a product of all the thoughts that I have during that moment that permeate the clay. I’m a very nostalgic person and I must highlight all those moments that will eventually disappear. I think that’s a big fear of mine – my ‘monster’.

What is your usual process for creating hybridisations and distortions of objects?

It’s not a process, it’s just an automatism. Bringing everyday things to life that we no longer pay attention to.

“Everything is important and nothing is trivial. I don’t have a specific method.”

You work a lot with commonplace objects. What interests you about working with them? You describe your work as ‘unique and precious banalities’, so it’s clear that you see a lot of creative and critical potential within these objects.

It’s like listening to the radio every day and hearing the number of people who have died from Covid, migratory accidents, wars and attacks; it hits us for a few seconds and then we continue with our daily life. Like the words of Hannah Arendt, its ‘the banality of evil.’ This might be a bad example, but humans make everything that doesn’t directly impact them uninteresting and unimportant. I’m not interested in the individualistic human.

I like the idea of asserting individuality and sharing it. I want to banish the idea of normality. Recognising its privileged position is the first step in thinking about things differently.

What is left on the day you die? The image of us, but it is not eternal. Objects into which we’ll have slipped a few words of love, the words on the back of a postcard, or a compilation of music that we have probably listened to hundreds of times. Life is abstract and complex, so you we should go beyond it and make the mundane things unique and precious.

What things outside of your practice do you feel are ‘unique and precious’?

The people we love and the mysterious things that bind us to them. I’m a lonely person (besides being nostalgic), but I love being around the people I love and listening to them talk. I love to read and taking the time to do nothing.

With the theme of this issue being Identity, I thought it would be interesting to hear your thoughts on how you explore your own identity through your work.

My artistic approach is mixed with my personal matters, it forms a hybrid. The evolution of my works reflects my own determination and of the way in which, little by little, I come into alignment with who I am. We must establish a harmonious cohabitation between our inner and outer being, between the angel and the demon. We should learn from our mistakes and accept that we will make them. The monstrous hand kind of symbolises this oscillation between the two sides of our identity.

Many aspects of your work revolve around monstrous forms. Could you talk a bit about how you explore the concept of the body?

I see the body as a hybrid object, something organic that evolves and distributes energy, both positive and negative.

Like J-M Gustave Le Clézio said, we’re contained in a sack of skin. I find once again that it’s something incredible yet minimised. Moving your body, feeding it, making it work properly is a wonderful thing and full of mystery.

I really like the vegetable head portraits of the painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo because he presents us with a vision that goes beyond our human limits, and which reminds us of the fact that we can be anything. We’re not that different to vegetables and we too will rot one day.

I’m also influenced by the chaotic landscapes of Jérôme Bosch, where we can see the energy of living and the beauty of heterogeneity.

Where do you see your practice heading? What can we expect from you in the future?

I’m working on many new projects. Hopefully I can still work collaboratively in the world of styling. I also want to explore new materials alongside ceramics. I have a solo show at the end of October in Brussels and joint show at the end of November in Amsterdam.

Credits

Images · NAOMI GILON

Interview · IZZY BILKUS

Discover Naomi Gilon’s work here www.naomigilon.com