“if I don’t experience and understand the moment I’m capturing, I can’t capture it properly”

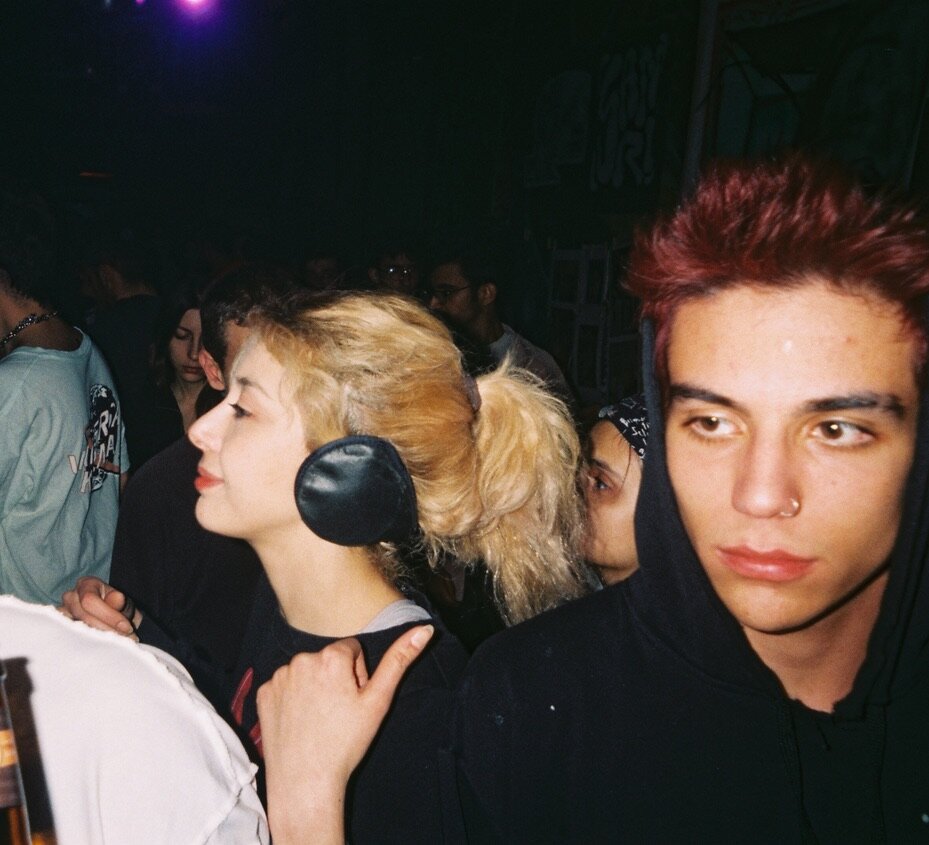

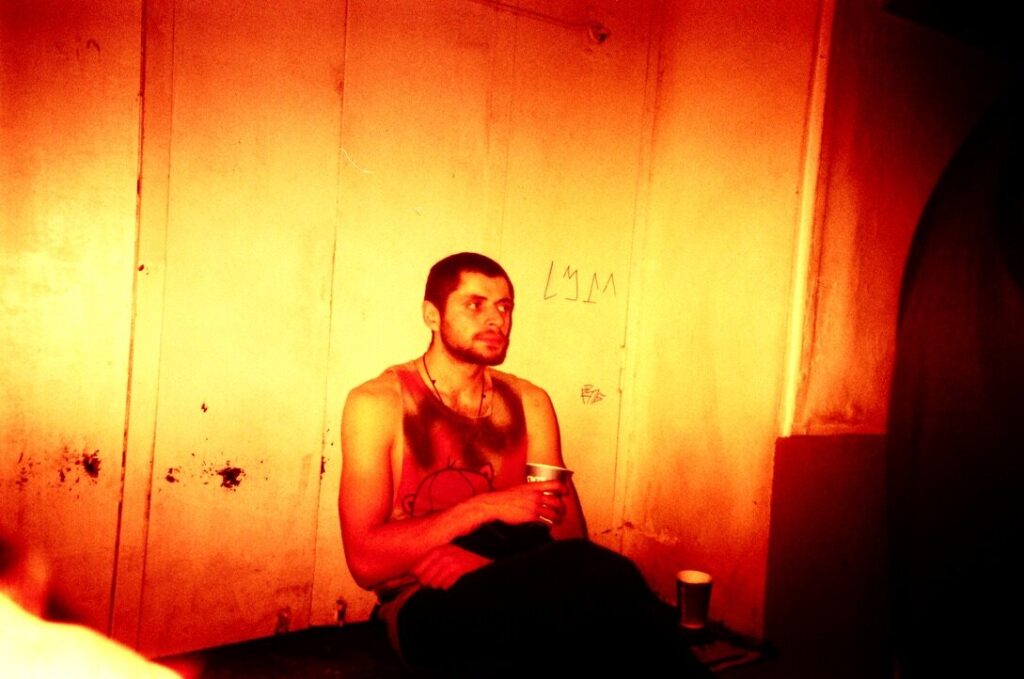

Dissatisfied with Turkish society’s attitude towards the country’s contemporary youth culture, photographer Kayra Atasoy captures the power and momentum of techno and rave culture in her project ‘Blame the Youth’ and uses the medium of photography as an outlet to explore and express aspects of her own identity. The ongoing project is inspired by the autonomy of the Berlin rave scene – a subculture that Atasoy resonates strongly with. Atasoy captures candid moments of these subcultures in her own country, that reflect the honesty and sense of freedom that she values most about these underground collectives.

‘Blame the Youth’ not only reflects the angst of the photographer, but also serves as a kind of visual manifesto for Turkey’s emergent youth culture, who Atasoy claims is simultaneously overlooked and criticized by the country’s older generation. The series features the influence of rave culture from overseas and how social spaces have been reshaped during the Coronavirus pandemic.

In the early hours of the morning, when time is irrelevant and all limitations disappear, Atasoy observes everyone’s true selves. It is in these magical moments that she is able to investigate her own identity through the lens.

NR Magazine speaks with Atasoy to learn more about the inspiration behind the project and what it is like being part of the subcultures she documents.

What initially attracted you to photography as an artistic medium?

For me, photography is a profession that offers immense excitement to my life.

A camera provides me with all the power of capturing, interpreting, and reflecting my point of view of a single moment, which is an amazing feeling. My way of truly living and experiencing life is through observing. Regardless of the topic, I always feel the strong urge to observe and watch. This is one of the main reasons I chose photography as an artistic medium. I love to observe life, and I love reflecting on the way I perceive it. Photography is my way of communicating my own perspective.

What’s been the biggest lesson learned from creating your series ‘Blame the Youth’? Have you discovered anything about yourself in the process?

One of the main things I learned was how various aspects of my life such as my environment and my mental health affect my work directly, and how this happens without me even realising it. One of the biggest takeaways I got from ‘Blame the Youth’ was that it helped me to fully understand what I want to do with my life.

Could you talk a bit about how you feel Turkish society blames the youth?

Unfortunately, I think we are a minority in Turkey. I believe the ‘youth’ that has been blamed by society is representing a minority. This isn’t something I’m always reminded of, as I’m always surrounded by this ‘minority’. Our struggles, our ways of having fun and creating aren’t understood by the rest of Turkish society. I think ‘Blame the Youth’ is a unique resource. It doesn’t matter where I take my photos; I could take photos for this project in Turkey, Germany, Spain, etc. The places where I feel this sense of ‘blame’ changes of course. I’m not a professional – I’m still trying and learning. Most of the support I get for my work is from abroad. This is obviously really motivating, but at the same time, not getting the same support from my own country is a bit upsetting. Even though I’ve got appreciation and encouragement from the people around me, my work doesn’t get the overall support I hoped for from my country. ‘Blame the Youth’ is a project where the name and the photos both contradict and complement each other. I believe that this juxtaposition reflects the current attitudes towards Turkish youth culture within our society. In Turkey, people are used to being judged and blamed. We don’t feel safe the second we stray from our circles. We learn to live by the rules, limits, and judgemental looks. I think my work documents all the moments where society feels it has the right to judge us. It’s not only about the parties, alcohol, and drugs – it’s also about the way we dress and the way we choose to live. As I continued to travel and explore, I realised that the way I choose to live makes it hard to live peacefully in Turkey. As I’ve mentioned before,

“I’m not the best with words, so even though I can’t stand up to this problem verbally, I try to communicate my principles visually through my photography.”

Do you set out with an aim in mind for shooting, or is it more a case of enjoying the freedom of the moment? I imagine it makes more sense to go with the flow and to fully immerse yourself in the moment when photographing techno and rave culture. And is living in the moment important to you?

I’d say yes, as the foundation of my photos is rooted in being in the moment. I am always looking for ‘the moment’. Observing and capturing spontaneous moments gives me much more joy and excitement compared to setting up a shoot. It might seem like I’m missing out on the moment while trying to photograph it, but this is my way of experiencing that moment. I have a strong desire to show my interpretations of things. When I take photos for ‘Blame the Youth’, I don’t just stand back and observe – I experience the same moment with the people I photograph, and I think this has a great influence on that desire. I strongly believe that if I don’t experience and understand the moment I’m capturing, I can’t capture it properly.

“Even though it might seem like I’m just a bystander, I see myself as the main character living in that specific moment.”

Are there any particular aspects of the techno and rave scene that influence you the most?

The first time I experienced techno music was in Berlin. It was the first time I was introduced to this music culture, and it had an immense impact on me. After that, I started reading, researching, and listening to it more. After scratching the surface, I discovered that these rave scenes have so many levels to them. The rise of techno music after the fall of the Berlin Wall, empty factories were being taken over to host illegal raves and there was a lot of rebellion amongst the people who were separated by the wall – this affected me deeply. I realised how the rebellious nature of techno music correlates with Berlin’s history. Just like ‘Blame the Youth’, I also realized how these things are rooted in a specific frame of mind, and not solely about partying. This led me to give more thought and understanding towards the meaning of music and I began to watch people even closer. Even though techno and rave scenes don’t have the same history in Turkey, I wanted it to reflect the rebellion and suppression within itself.

How has your work been received in Turkey? Do you find your way of working to be controversial or rebellious?

As I mentioned before, my photographs haven’t received a lot of recognition in my country. Even though I took those photos in Turkey, I felt more understood by other countries. This is quite an upsetting situation, as I believe my work honestly reflects Turkey’s reality. To put it another way, despite Turkey’s prejudice and ignorance, we are here, and we will always be here. Our struggle isn’t built on our desire to be completely accepted. We just want to live freely and not feel any guilt or shame about it. I want to do my job freely and have fun doing so. For those reasons, I consider my work to be both controversial and rebellious.

“It’s a struggle to just live and to make ourselves seen.”

Do any aspects of your own life influence your work?

My life and the photos I take are pretty much integrated, and I love that. I’m a part of the culture that I try to photograph. When I’m photographing, I capture myself in some of the shots. I won’t work on ‘Blame the Youth’ forever, so I like to experiment with different ideas, and will continue to do so. I think ‘Blame the Youth’ will represent a culture and an era that will live on forever. I want to reflect on life the way I experience it. I don’t want to share a moment if I haven’t experienced it.

There is a story and a continuation of subjects in my work. The people I photograph are a part of my life, so I’m able to shoot them in a rave scene, and also capture them at home in a completely different atmosphere.

You’ve mentioned that Berlin is a big inspiration for your work, and how you felt a different sense of freedom there compared to being in Turkey. Could you talk a bit more about that?

In Turkey, it is hard to live as a woman, and it is even harder to stand on your own as a female artist. When I was in Berlin, I felt safer, and I had the chance to observe different subcultures. The government-supported techno parties are incredible. I think that was the reason I always considered Berlin to be my inspiration. I bought plane tickets to Berlin when I first got the chance. I stayed there by myself and got an incredible opportunity to observe. Every time I came back to Turkey, I just felt increasingly restricted. One of the biggest reasons for this was feeling judged – another core aspect of ‘Blame the Youth’. We were always told that we were doing something wrong.

“Being able to confidently say ‘I’m a photographer’ isn’t an easy thing to do in Turkey. That’s why I don’t feel like I truly belong in my country.”

How has the pandemic affected youth culture in Turkey? Have you found it a struggle to stay creative and inspired?

Two years ago, just when I started to recognise my career growth, the pandemic hit. Around that time, ‘Blame the Youth’ was getting recognition not just from Turkey, but around the world. When we were quarantined at home, it was a real struggle to find motivation. I forced myself to be motivated for a couple of months, and I realised that the potential of ‘Blame the Youth’ extended beyond the streets, clubs, and parties. The people I photographed were still the same, and so they would continue to be a part of this culture regardless of time and place. During the lockdown, I began to photograph moments of distress that we all felt. Throughout this period, I tried some work, but despite how much I tried, I found that I was always better at capturing an instantaneous moment. Even though I was working on editorials, I was only fully satisfied with these instantaneous little moments I captured. The lockdown provided us with a break to be introspective I turned my camera away from the chaos around me, and focussed on fewer interactions, fewer people, but still the same audience.

You’ve discussed capturing ‘magical moments’ – what do these moments look and feel like to you?

‘Magical moments’ are the moments where people are being their true and spontaneous selves. They are when I capture people dancing without the fear of being judged or watched. The photos I take are divided into two groups: the people who know that my camera is on them, and the people who don’t. When people are aware that they are being photographed, it disturbs the truth and the spontaneity of the moment. When people aren’t aware of the camera, I’m able to shoot pure moments that I define as being ‘magical’.

What are your favourite moments to photograph?

Probably the moments I capture without overthinking – they end up being the best possible moments. When I’m out there with my camera I’m always in a rush: observing, running, dancing – there’s only an instant between observing and shooting. I usually realise later that I pressed the shutter button at the perfect time, to capture a moment that I wouldn’t have been able to capture if I pressed the button even a second earlier. These are the shots that turn out to be the most satisfying ones. These are the shots where the subject is completely in their element, unaware they are part of this perfect moment. I always want to capture reality, but from my perspective.

What do you have planned for your work in the future?

After graduation, I would love to create a path that enables me to travel more and experience different cultures. I will be spending this winter in an analogue studio’s darkroom in Budapest for an internship. I’ve also received exhibition offers from London. If everything goes according to plan, I will spend around two weeks in London for this. I want to create deeper levels of meaning with ‘Blame the Youth’, whilst also observing new cultures and new people. I will eventually head back to Turkey, but for a while, I just want to travel and shoot. I want to be able to make a living through my photography. I can’t picture myself doing anything else.

Credits

Discover Kayra Atasoy’s work here www.kayraatasoy.com

Images KAYRA ATASOY