“Photography is my interlocutor.”

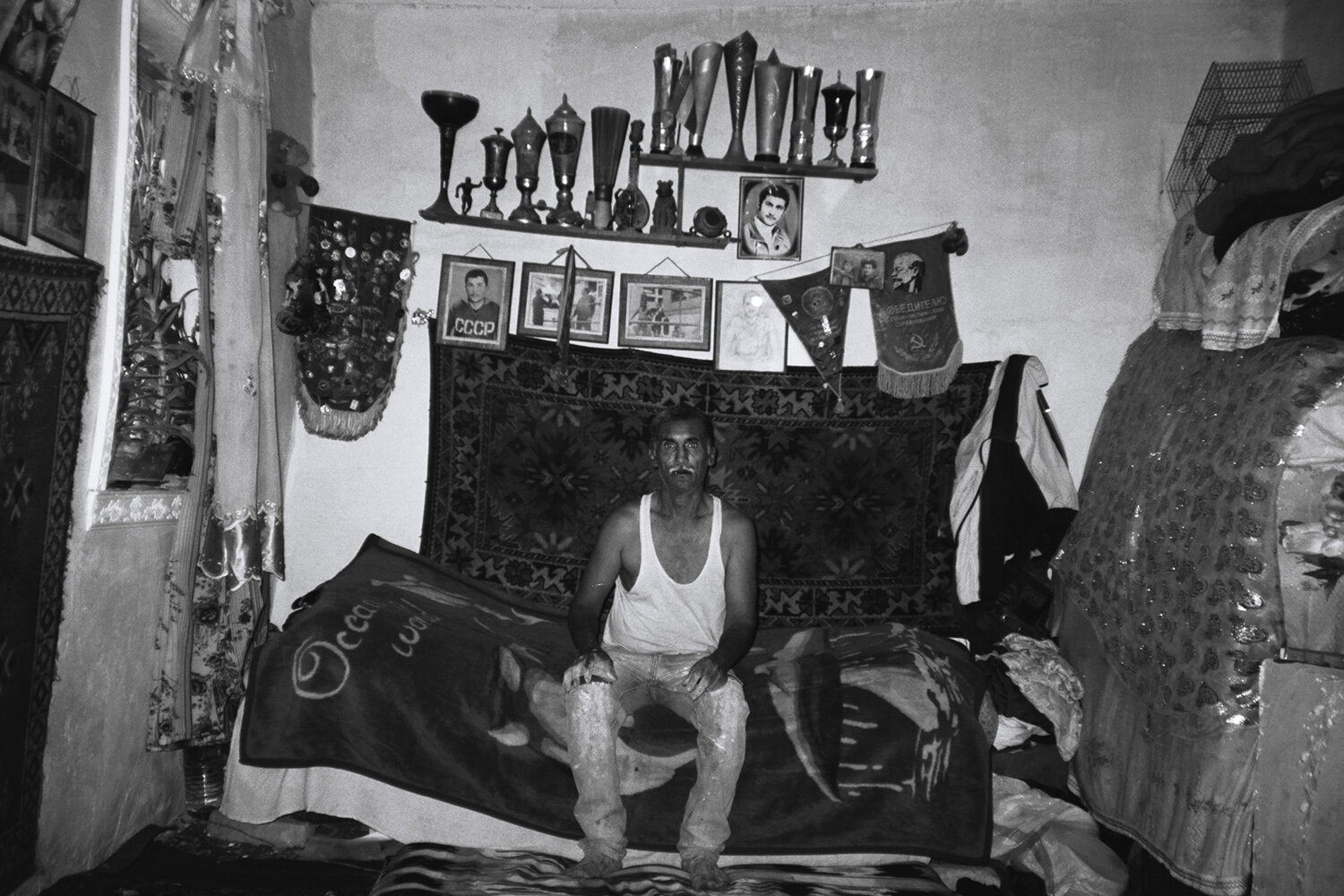

Shining a light on the hidden gems of Uzbekistan, photographer Hassan Kurbanbaev documents and explores the identities of the people and landscapes of his home country. Capturing the spirit of the country’s capital city Tashkent, Kurbanbaev’s also uses photography as a tool to better understand his surroundings. Immersing himself in the country’s emerging generation, his sentimental perspective shines a warm light on the often-overlooked aspects of Uzbek life.

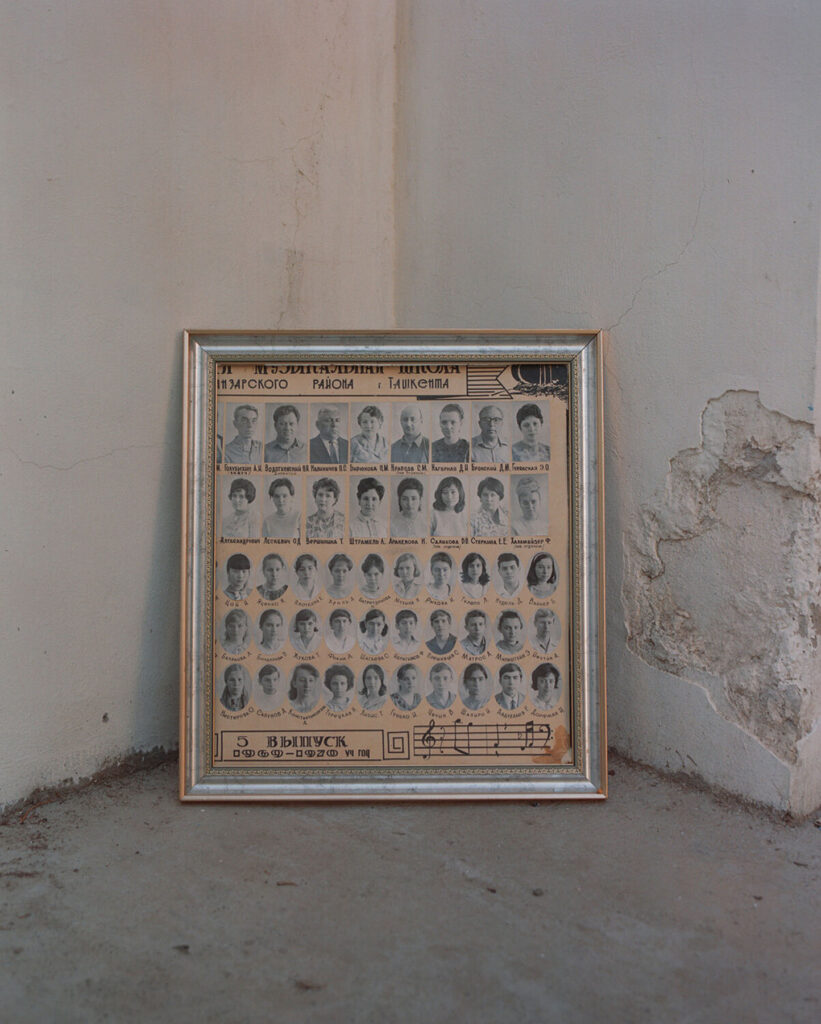

A Soviet republic for the majority of the 20th century, Uzbekistan became independent in 1991, and the country’s history of immigration has made Tashkent a city of great diversity. Kurbanbaev’s body of work reflects this richness of culture, as he documents Tashkent’s youth, inner city spots, rural landscapes and personal portraits. Snapshots of urban life bathed in sunlight, trees caressed by the breeze and locals lost in thought – the photographer’s love for his city stands out in his work.

Kurbanbaev’s work has planted the seeds for a new era of liberated image-making in Uzbekistan. Championing authenticity and showcasing his heritage, he speaks into existence a new kind of artistic expression for the Uzbek photography scene and inspires other emerging artists to do the same.

NR Magazine speaks with the photographer to learn more about the history of artistic censorship in Uzbekistan, the blossoming photography scene, and Kurbanbaev’s exploration of his country’s identity.

When did you first start getting into photography?

I took up photography while studying at the Tashkent State University of the Arts, where I entered the Faculty of Cinematography in the early 2000s. Now it’s slightly difficult to call this university a full-fledged education, but at the time we had a photography course that helped me understand that it was something I’d be passionate about in the future. After graduation, I didn’t immediately become a photographer in the full sense of the word. I worked for several years in radio and did various jobs, but eventually returned to photography as a profession. I guess I understood photography as something that made my existence useful and conscious.

You’ve mentioned being ‘full of questions’ about your ‘identity as a citizen of Uzbekistan’ – as this issue of the magazine is about identity, I’d love to delve deeper into your thoughts about that.

I think that I, like a lot of other people from the post-Soviet era, experience this feeling of uncertainty about questions concerning the concept of self-representation, a homeland and community really means for us.

Uzbekistan with its modern borders was formed by Joseph Stalin, who personally laid out every centimetre of the border. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan retained a totalitarian-type, autocratic, harsh regime that was present for many years, which of course stopped any real understanding of yourself and the place you live. Instead of turning to a critical study of history and our national identity, we turned to propaganda and a constant zombification of Uzbekistan being ‘a country with a great past and a great future’. You just don’t believe what you’re being told – something inside you resists. My childhood in the 90s was when Uzbekistan became independent, and at the start there was still a sense of freedom – the borders opened, we had MTV, and I was definitely shaped by that feeling of freedom.

Uzbekistan slowly started to return to its old ways, which prevented us from accepting ourselves as part of the country. I come from the south-west of Tashkent, where they mostly speak Russian, and I was also raised in a Russian-speaking environment, so this was also part of what confuses me about my identity. These internal conflicts have haunted me all my life. Photography helps me to constantly examine my country from different angles and to seek the truth, even if it’s not something I reflect in my work. Photography is my interlocutor.

Your work, and ‘Untitled (Portrait of Uzbekistan)’, stands out as an exploration of your country and the things that unite it. Has documenting the people and places of your home uncovered anything in particular for you? Have any specific moments resonated with you?

Yes, I think my love and respect has grown for the people living in the provinces and small towns. They are very hardworking and good people, able to withstand many hardships that life has presented them with. I don’t know if I reflect the determination of their spirit in my photography, but when you are with them, you definitely feel it.

Your work is the first I’ve encountered of its style that details life in Uzbekistan. It is clear that life in the rural parts of the country is often overlooked – is that something you wanted to change through creating the series?

From a visual archive stance, modern Uzbekistan and personal photography in particular lacks a solid foundation. By and large, Uzbekistan is well represented in the colonial view of the past few centuries, and as an almost ideal picture from the Soviet Union, but in contemporary photography, there are only a few series from local photographers that have an impact on the Uzbek photography scene. Personally, I couldn’t name more than three people that have gained recognition documenting Uzbekistan or that have had their work published in books. The country itself is interesting to me and as I travel, I learn more and try to share this experience. To me, it seems that now is the time for local photographers to document their city, or anywhere they feel connected to. The most important thing is expressing your opinion and your viewpoint as much as possible – this is the only way to form a new community of photographers, and a community in Uzbekistan, which I think should then be transformed into an institution.

As a photographer, how do you find life in Uzbekistan?

Only from about 2016 did I feel motivated to work here as a photographer. The country has changed for the better over the years, but some reformation processes have slowed down.

Most of the photographs in the series are portraits, but there are also poignant still lifes, as well as sprawling landscapes – does the natural environment and the Uzbek landscape have a big impact on you?

I am not a naturalist or a landscape photographer, but I do love nature, and sometimes I find it necessary to spend some time in solitude with it. Landscapes and still lifes are just a continuation of the study of my country through the eternal images of nature.

Do you ever find it hard to explore your creative freedom given such a long history of censorship where you’re from?

Yes, it happens constantly. Some artists I know still have a fear of putting themselves at risk with their work. At the same time however, I think that now is the time to act on and explore topics that wouldn’t have been possible previously. I don’t limit myself in what I do, but I know that at any moment everything could change. You never know what tomorrow might bring.

The 139 Documentary Centre in Tashkent has become an important place for the photography scene in Uzbekistan. Could you talk a bit about its impact on you?

It would have been impossible to imagine this centre opening a few years ago. It is a small but important organization that is finally really engaged in visual research of Uzbekistan, through documentary photography and exhibitions of young artists. The centre has helped support artistic freedom, which has been much needed for the arts community in the country for many years. I’m very glad that I held my first solo exhibition here.

What has it been like over the years having more freedom to document what you want? Has there been a noticeable difference in your creative process now to back when you first got into photography?

It has not been an easy journey, and I feel like I’m just at the beginning of it. Photography is a plastic medium and requires constant commitment. I am changing along with the country. In other words, this is my evolution – from an amateur fashion and stock photographer, to rethinking my work, understanding the key moments, and constantly learning in my profession.

You’ve mentioned how important it is for Uzbek artists to document and speak about Uzbekistan. How else does identity and your hometown Tashkent inspire and influence your work?

I’m an introvert, and sometimes to get some time away from everything, I walk for hours in the city, in the courtyards or along the road. It has always helped me in the worst moments of my life, especially as a teenager. Tashkent has always been my friend. In 2016 I returned to photography after a break, I began to photograph my own city and its youth. This helped me return to my profession. If all Uzbek artists address their community, it would be so cool – we really need a variety of stories! But then again, I know that a main problem is money. Young artists don’t have money to fund their own projects, and I often experience these problems myself.

How has the pandemic affected Tashkent?

2020 was a frightening reality for the whole world. Like the rest of the country, Tashkent, was no exception. The pandemic obviously affected the economy and peoples’ way of living. For example, we had economic migration to Russia and Kazakhstan, and many people were unable to work to earn money for their families. I don’t know how they survived.

What do you anticipate for the future of Uzbek photography?

I think in five or six years you’ll recognise some great projects from new artists in Uzbekistan. We live in a time where we can use a platform like Instagram to help realise and share our thoughts and ideas. I think that if censorship doesn’t return to my country, then our future is bright. But in general, being an artist in Uzbekistan is hard.

What inspires you about other Uzbek artists?

This is a great question! If we’re talking about photography, there are some young photographers that I follow on Instagram who I met at the 139 Documentary Centre. They work in the same genre of subjective documentary, and there is a lot of personal touch to their stories, which inspires me the most.

Your series ‘Logomania’ explores how signs and symbols of Western culture have become deeply embedded in the daily lives of people in Uzbekistan, and you’ve commented on how this has had a devastating effect on your country. Could you talk a bit more about this and the ‘crisis of self-identification’ that you’ve mentioned?

After almost a century-old totalitarian regime, Uzbekistan gained freedom, but at the same time there was an increase in the uncontrolled import of poor-quality goods. This is how the market was formed, influencing our perception of beauty and prosperity, and it strongly influenced the emerging culture of Uzbekistan.

Globalization and the lack of vital improvements in education made us dependent on everything Western, and as a result, we formed a mediocre culture of self-identification that was reflected in everyday life. For the series I looked at this problem through the lens of everyday fashion, which is fascinating to me. In these gold Gucci patches on the velour local dressing gowns, I saw everything I mentioned above.

What do you value most about Uzbek culture? Do you have any favourite people or places to photograph?

I appreciate their modesty, humility and their great love for life. I appreciate the strength of our people who bring goodness and light into this unjust reality. I am still exploring my country, so whatever I photograph now becomes my favourite place.

Do you have a particular process when shooting or is it just something that comes naturally to you?

It depends on the projects, for example, Logomania is a completely staged project, but most of the time my process is candid – my friend and I collect backpacks with cameras and travel without a specific aim in mind.

Are you working on any projects at the moment?

Yes, I am working on a new project that investigates the changes in Uzbekistan 2016 to the present day.

Discover Hassan Kurbanbaev’s work here hassankurbanbaev.com