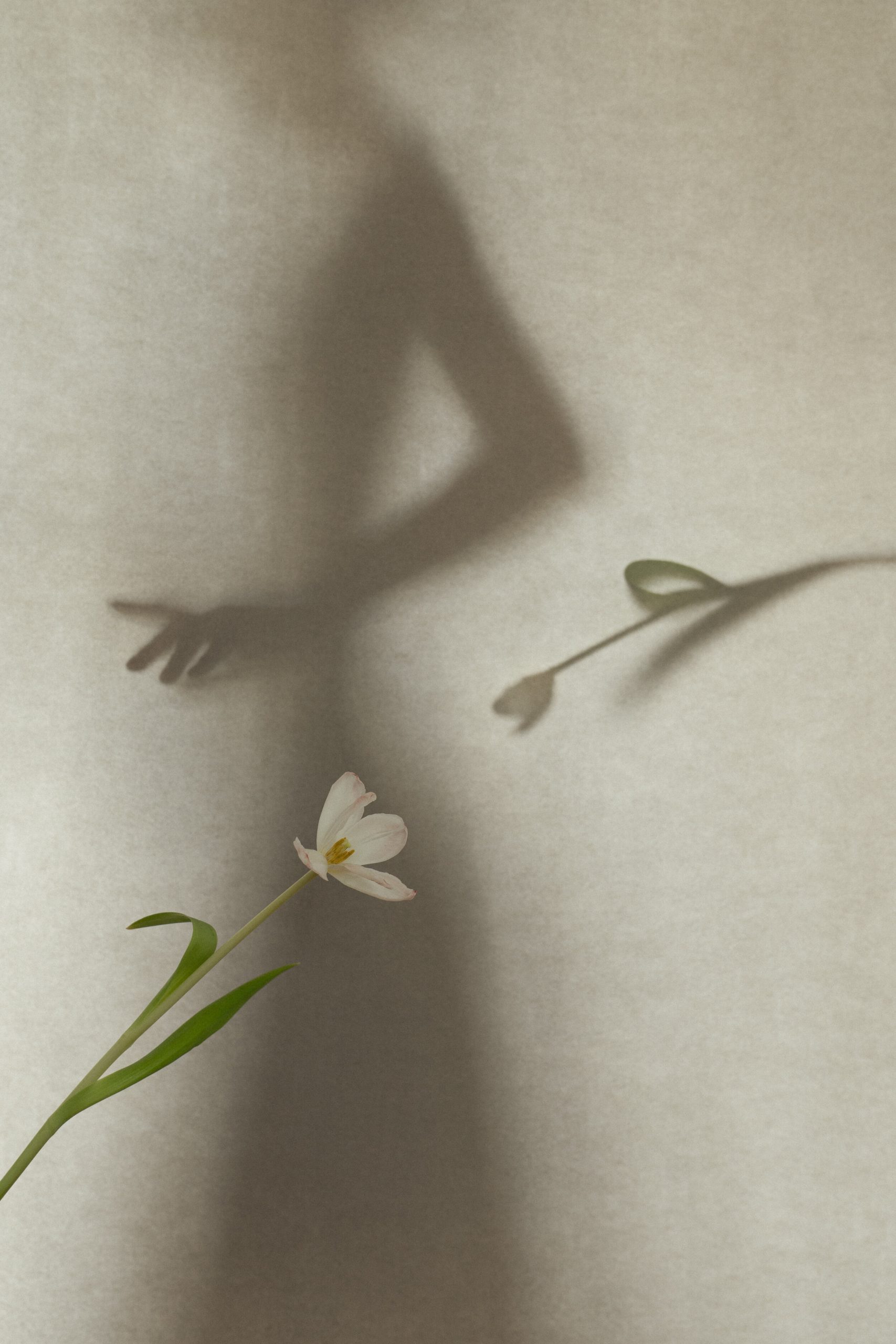

“props are not only objects, but also something that brings me ‘knowledge’ through photography.”

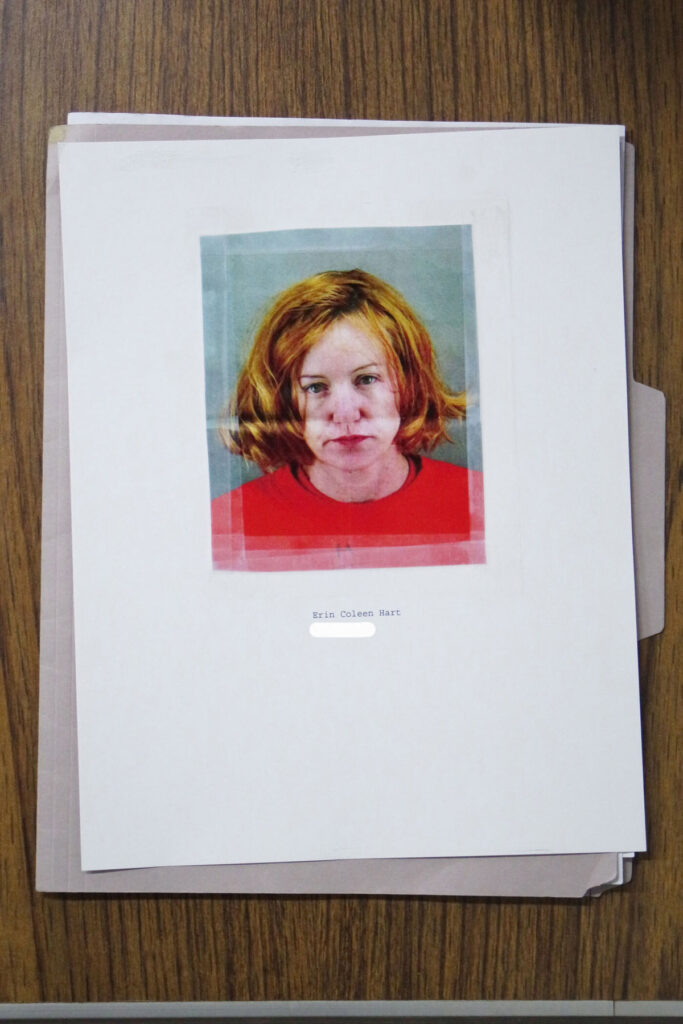

A faceless woman with black hair is reflected in the round silvery disc of a mirror. Surrounded sometimes by flowers, sometimes by fruit, these photographs are minimalistic and infinitely satisfying. Ziqian Liu is an independent Chinese photographer who developed her self taught practice whilst struggling to find a full-time job after graduation.

Liu explores two main themes within her work. The first examines the “symbiosis between human beings and nature” She states that “to some extent, it can be said that human beings and the rest of the natural world are equal – we live in the same world, breathing the same air, mutual tolerance.” Because of this, she attempts to illustrate a state of harmony between humans and nature within her work.

Secondly, she investigates the theme of perspective. Through her work, she conveys the need to scrutinise the same thing from different angles so one might discover different findings from the ones we already know. While she desires symmetry and order she understands that this is not always possible in an imperfect world. “In her work, the image in the mirror represents the idealised world she wishes to live in, and the integration with the outside is just a reminder to respect and recognise the imbalance in the real world, but also to adhere to the order and principles of our hearts.” NR Magazine joins the artist in conversation.

You have said that you want your photographs to show a peaceful harmony between humans and nature. However, is it even possible to have that said harmony in a post-capitalist society, where even with ethical sourcing the props you use in your images, such as the flowers and fruit, might have had a negative impact on nature?

I think the harmony mentioned still exists.

First of all, the props used in the pictures are all things that will be involved in my life. I will not prepare the props or throw them away for shooting but shoot what is in the home. Flowers are always in my home; they are my good friends. Fruit or vegetables are also on the menu of the day. In fact, when I shoot, I usually use the plant as the subject and myself as the prop. I will not deliberately change the form of the plant for the sake of the picture, but let my body match the inherent posture of the plant.

In the post-capitalist society, knowledge is in an irreplaceable and important position. Of course, I don’t think there is a clear boundary in the scope of knowledge. I think these props are not only objects, but also something that brings me “knowledge” through photography. I gained knowledge about plants while taking care of them, but more important is the change that solitude brought to my heart during shooting. The whole process was very positive and harmonious for me.

You have said you use mirrors in your images because you want to create the feeling of another reality within your work. Mirrors have often been considered as a bridge between reality in both mythology and popular culture, such as Louise Carol’s Alice Through the Looking Glass. Are these cultural stories something that has inspired you?

In the beginning, it was a very coincidental reason to use mirrors in the images. Originally, I was just taking pictures of plants at home. When I had a rest, I picked up the mirror beside me to look at myself. At that time, I suddenly had the inspiration to try using a mirror in my photography. Later, I found this way of shooting is very interesting, so I stuck with it.

Later, when I saw works in which mirrors appeared, such as movies or even songs, I would feel very familiar, and I would pay special attention to the way mirrors appeared in these works, which sometimes brought me inspiration.

While you consider your work ‘a space that belongs to yourself’, you have also said that you want viewers to be able to imagine that the protagonist of these images can be anyone. Have you ever considered using plus-sized models or models from different backgrounds to create more diversity in your work?

Maybe I won’t consider a model for a few years. All my works are self-portrait to find the most suitable way to get along with myself, which is also the reason and original intention for me to stick to photography.

During the daily shooting, I was alone without any assistant or other people to help me. It is only when I am alone that I am most at peace and inspired to create these images. Sometimes I can only hear my own breathing. I can’t concentrate if I’m talking to people while I’m taking pictures. Secondly, only I have the best idea of what kind of picture I want to finish, such as how high the arm should be raised, how much distance is between me and the mirror, and so on. A very small difference will make a big difference. These details cannot be communicated with the model effectively, so I might insist on completing the work all by myself.

What does identity mean to you as an artist?

For me, identity is the same as occupation. It simply summarises who I am, but does not show the whole of a person. Identity is not important to me.

In fact, I only think that I am taking pictures in the way I love. I am very honoured to be regarded as an artist. This status also encourages me to continue to be myself, not to be disturbed by the outside world, and to shoot more pictures that can bring peace and beauty to the viewer.

You have mentioned your love for flowers many times and you often use them in your work. Do you choose the specific flowers according to their meaning? And if so does that meaning give a hidden message to each photograph?

To be honest there are no specific choices and no hidden messages. As mentioned in the first question, I only take existing flowers at home. Before I became a photographer, I always go to the flower shop every weekend to pick out some fresh flowers, I enjoyed the vitality of my home very much.

You have stated that you use your artwork as a way to get to know yourself. Do you consider your art as a form of therapy to help you come to terms with your identity in life?

I quite agree with what you said. I think artistic creation is a way for me to heal myself, just like yoga and meditation, which can bring positive effects to people.

Through photography, I find that the fusion of identity has a lot to do with the change of perspective, and the biggest feeling it gives me is that I can accept myself more easily. Before photography, I was very concerned about my appearance and looked in the mirror to see if there were any flaws that needed to be covered up. But by shooting with a mirror, I had a chance to see myself from different angles, and I discovered that the so-called ‘flaws’ have their own beauty, they are just a normal part of my body. I think the integration of identity has also led to a change in my mindset, a more positive and peaceful self.

Not long ago, I just summoned the courage to face a part of my body in front of the camera – the wrinkles on my stomach. It was the first time that I discovered the beauty of the traditional impression of “flaws”.

You have stated that you wish your work to be apolitical. Do you think that choice comes from a place of privilege, as many artists are unable to separate politics from their work, or is it a necessary choice for your own personal safety?

I don’t pay attention to politics too much in daily life, so the content of my works is mainly about the harmonious coexistence between human and nature, and has nothing to do with politics. But if when the political inspires my expression of desire, I don’t think I will withdraw.

You have said before that you enjoy solitude. Did you find that the pandemic allowed you to be more productive and was a fulfilling period in terms of your art practice?

Yes, I enjoy solitude. All my work is done in solitude. In my opinion, in art practice, the most productive period is before I found my shooting style, and the most creative and efficient period is in the groping stage.

As more and more pictures are taken, I set higher requirements for myself, hoping that the content and details will be more refined. And I don’t want to be confined by a fixed style, so I try to make some changes on the original basis, so it takes more time to complete a work now than in the past.

What advice do you have for young creatives who want to work with photography?

It is important to have confidence in ourselves, trying not to imitate. There is no good, bad, beautiful or ugly work. It is enough that the work comes from the heart and is sincere.

Are you working on any specific projects at the moment and what plans do you have for the future?

I like to let nature take its course and have no plans for the future. Now I am still working steadily on my own works.