«Repetition itself is life-affirming. The wavelength calming.»

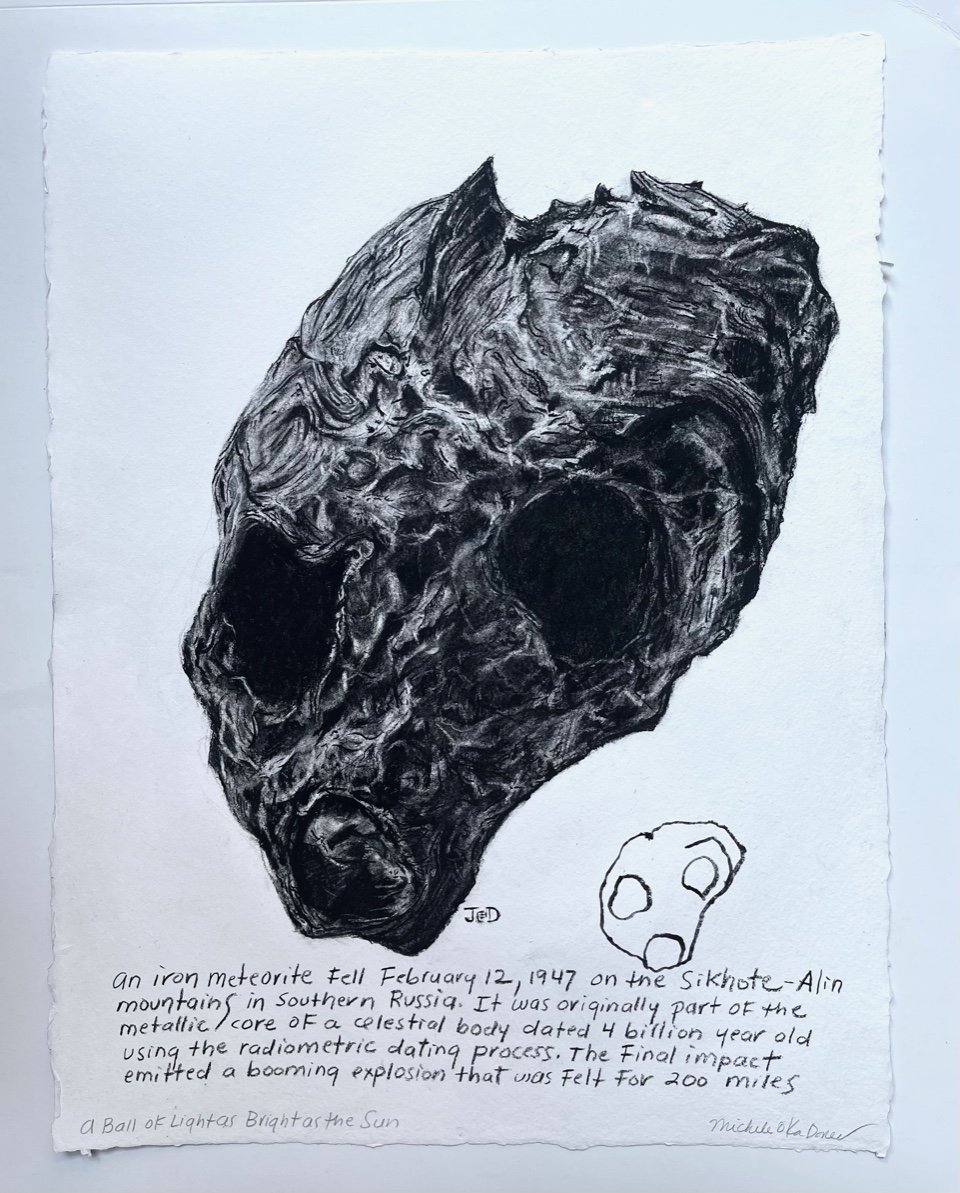

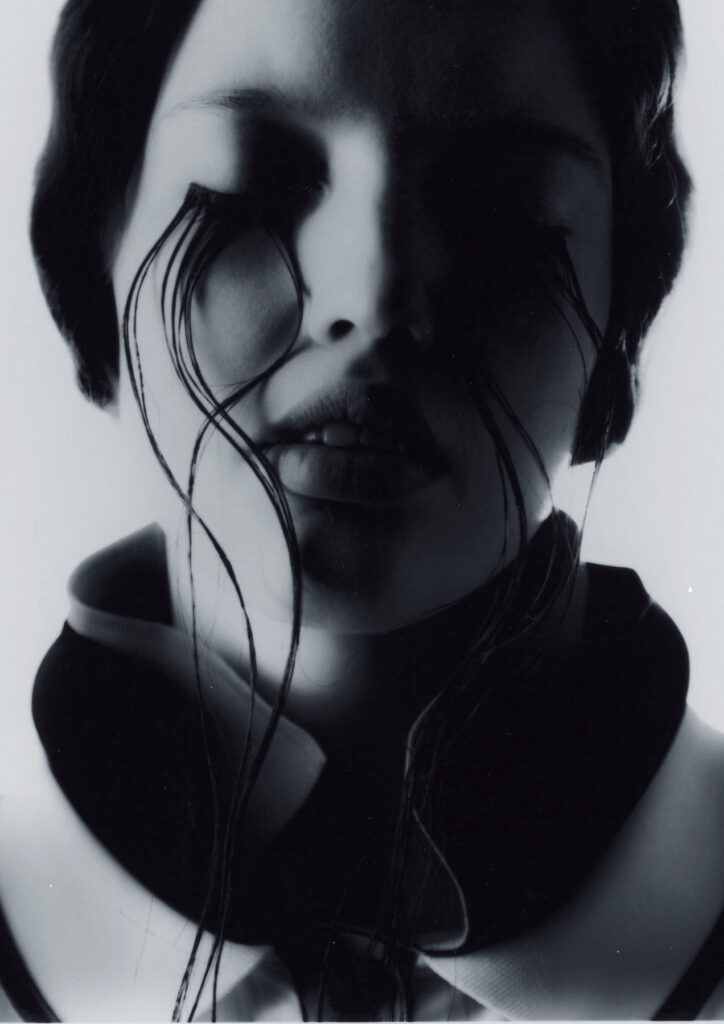

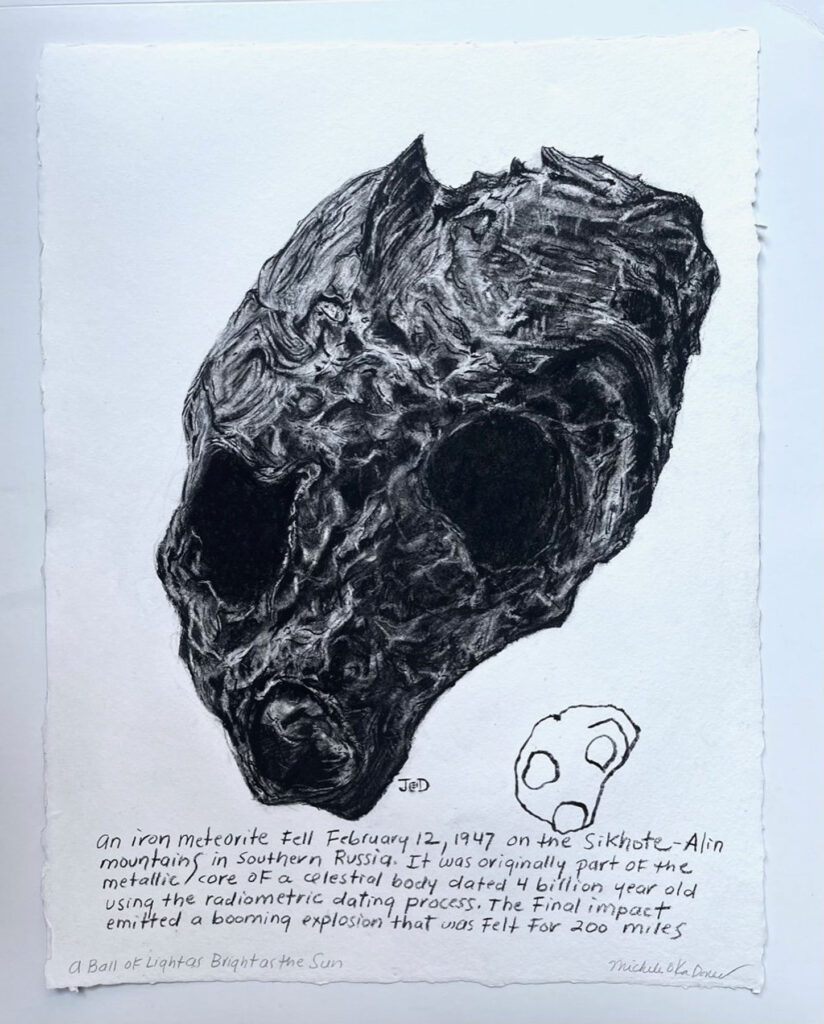

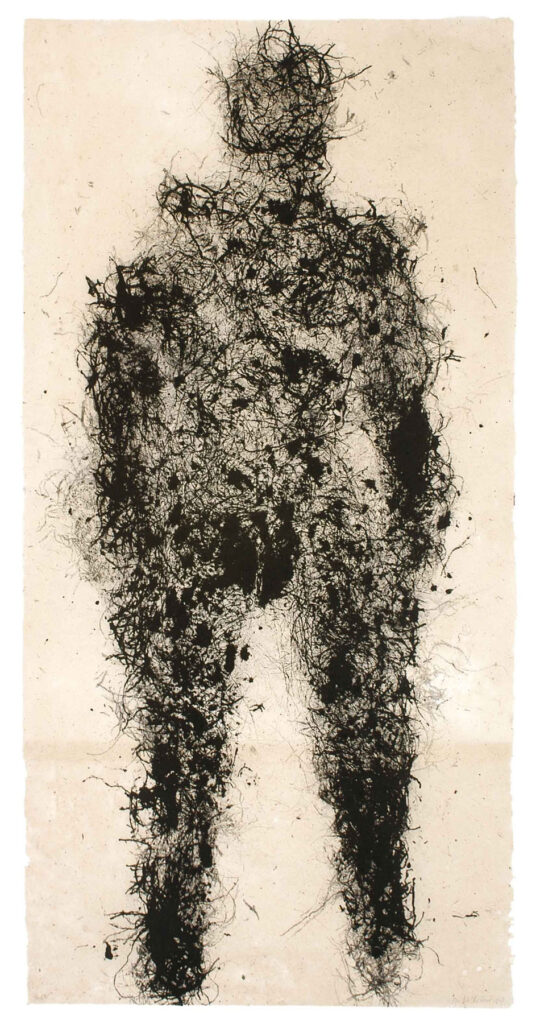

With a career spanning over five decades, American artist and author Michele Oka Doner’s work, which is fuelled by a lifelong study and appreciation of the natural world, is internationally renowned. She has worked across a wide range of mediums including “sculpture, public art, prints, drawings, functional object artist books, costume and set design and other media.”

Doner grew up on Miami Beach, and her love for the natural world comes from her father who was elected a judge and then, mayor of Miami Beach during her childhood. She states that while she loved watching him work in the courtroom, it was his passion for the outdoors that would inform the rest of her life. “As busy as he was, my father would pause to watch a bird sit in a puddle after the rain. He’d stop for a sunset. He paid attention.”

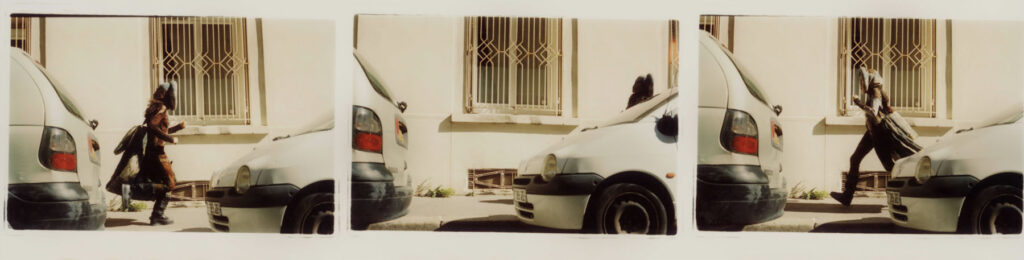

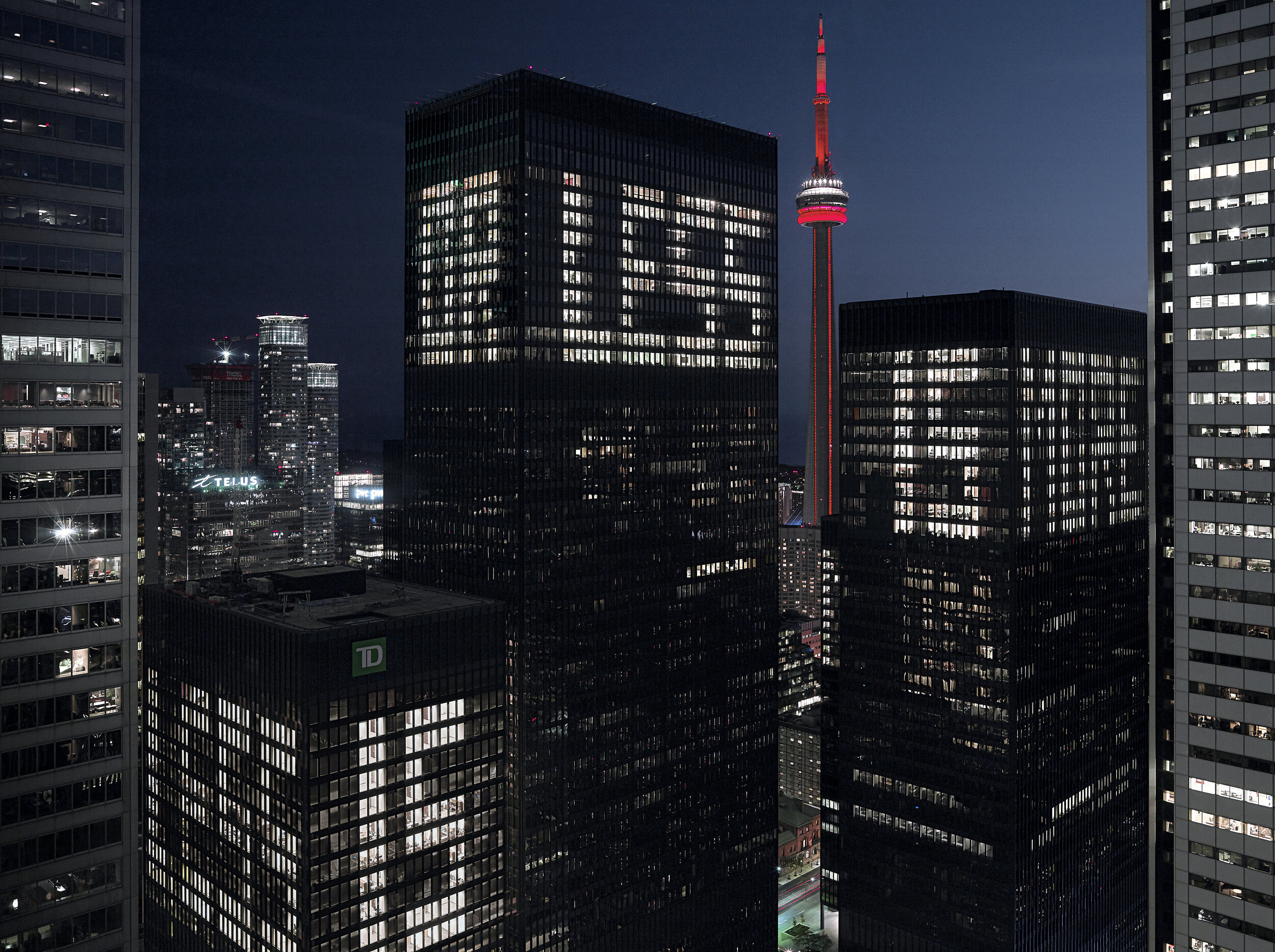

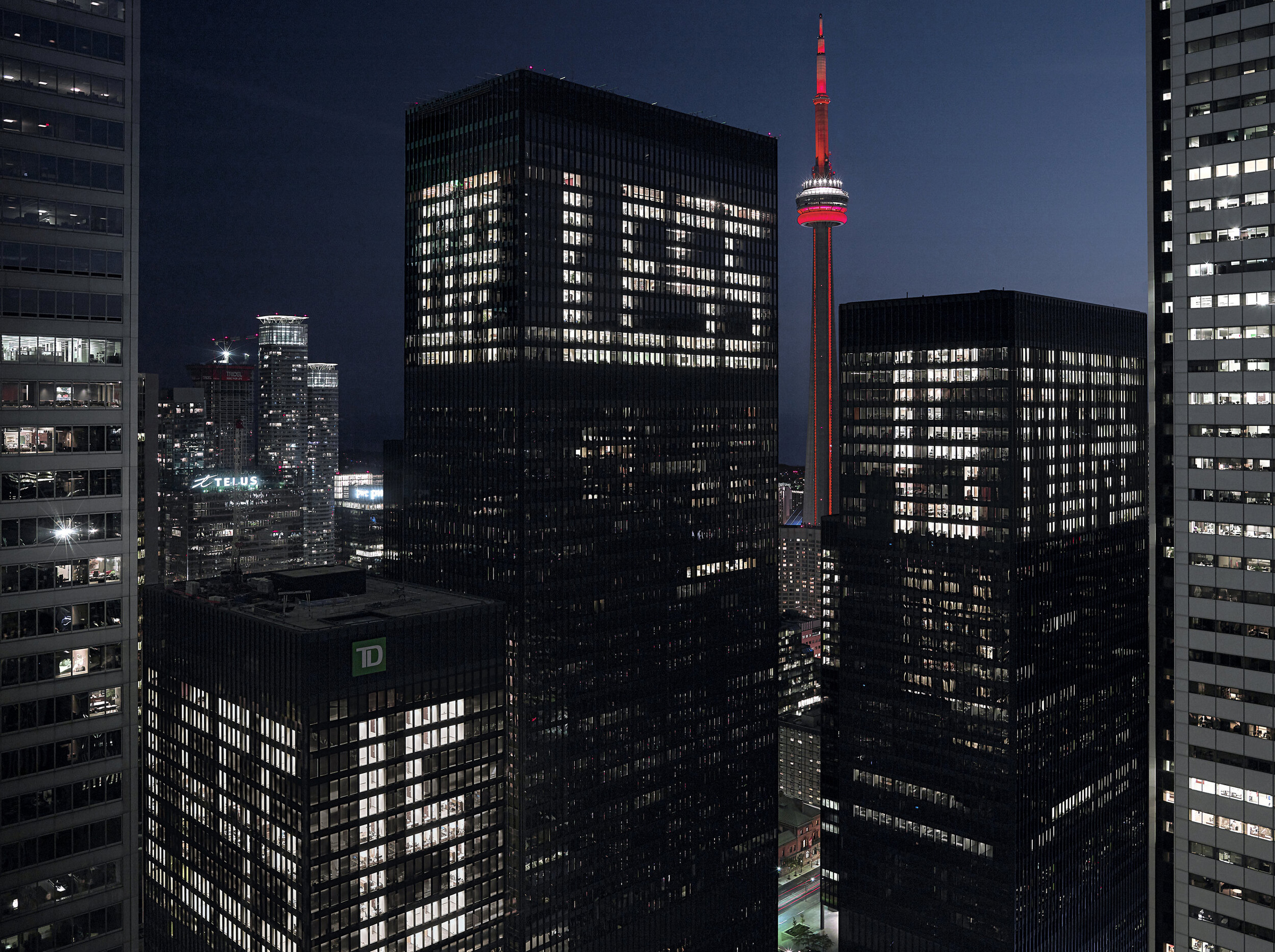

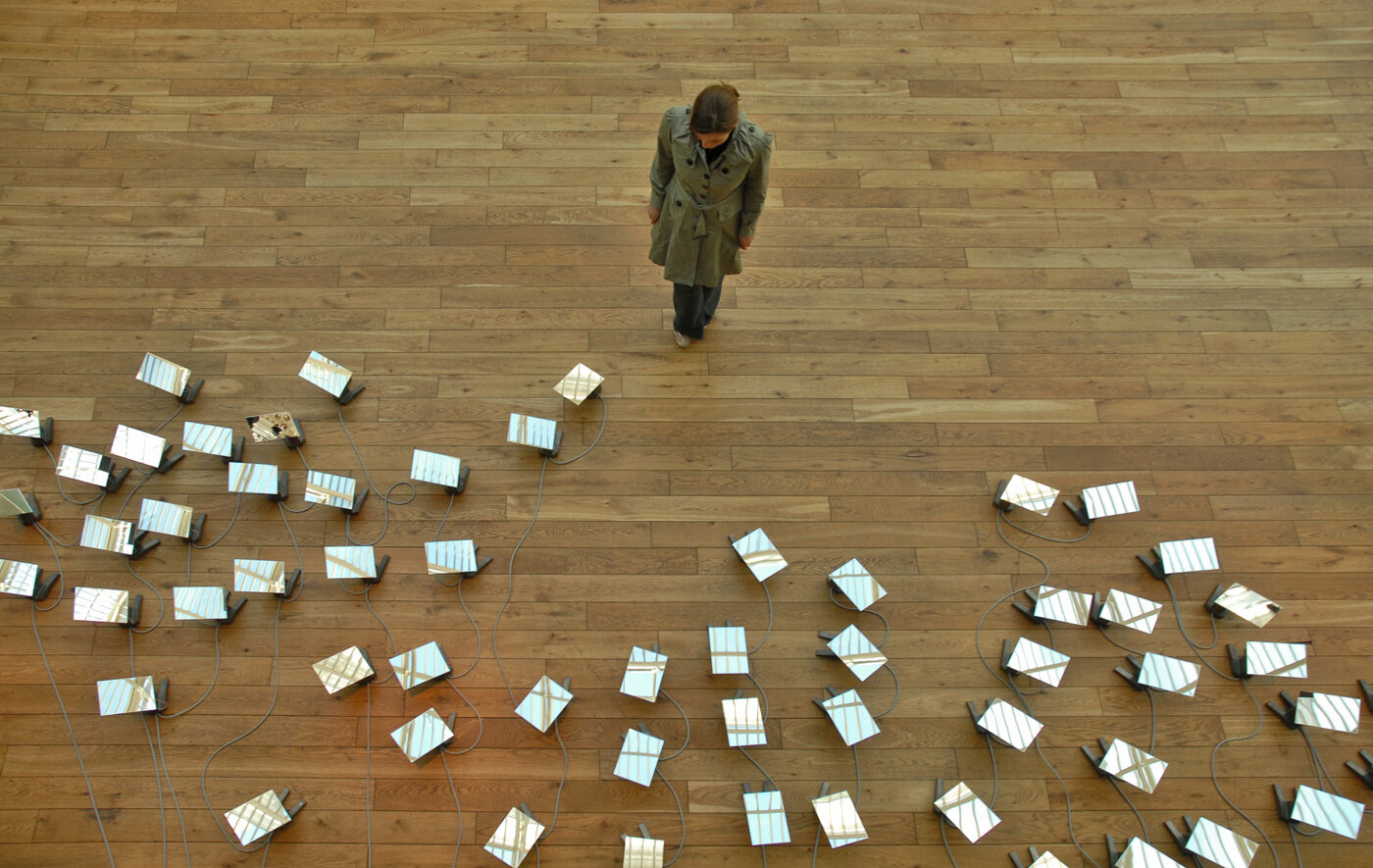

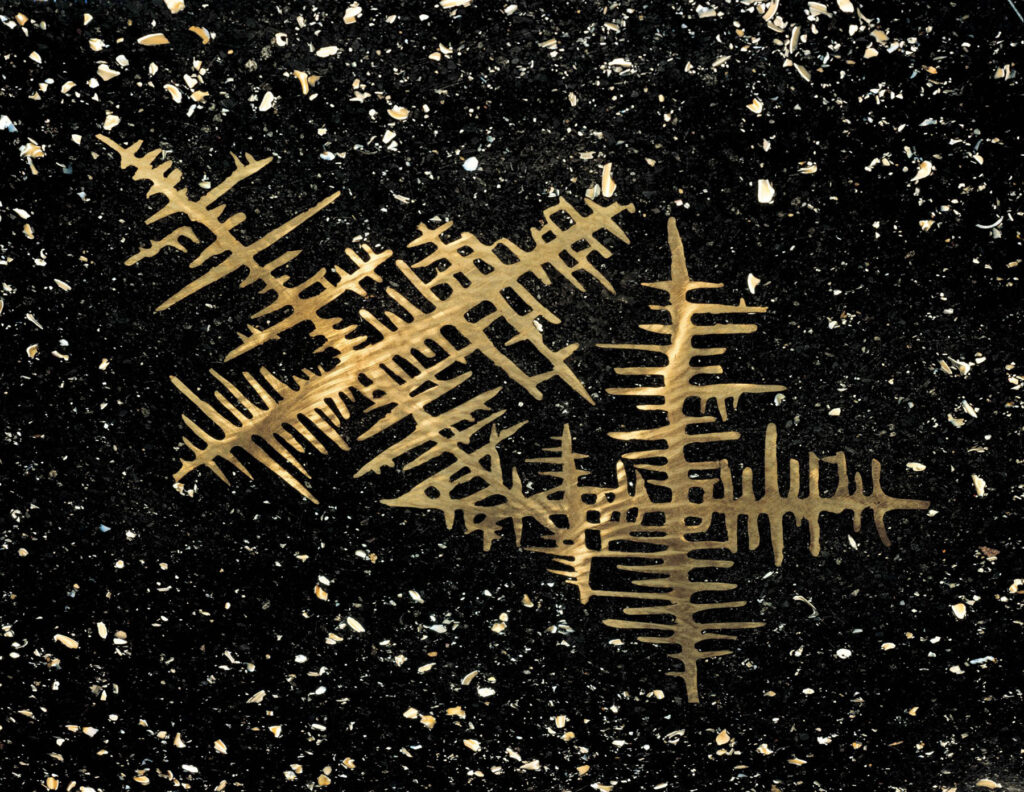

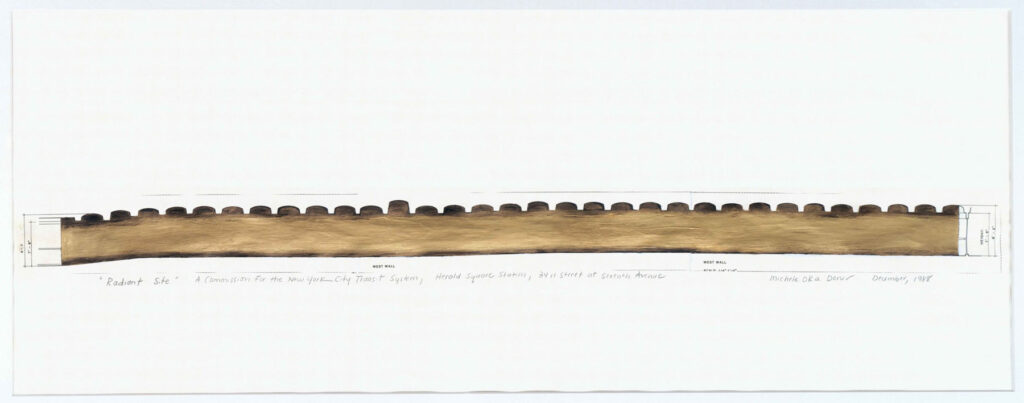

Best known for her public artworks, Doner’s work is seen by tens of millions of people are they are located in areas with high foot traffic. One example of this is ‘A Walk on the Beach’, a mile and a quarter long artwork made of over nine thousand bronzes embedded in terrazzo with mother of pearl, at Miami International Airport. The work is inspired by the marine flora and fauna of Miami.

She continues to make work in her New York studio where she has worked for nearly four decades and the space is crammed with unfinished and competed works, alongside a treasure trove of found objects such as animals bones, shells, stones and fossils. Donna states that she is a “hunter-gatherer” and that despite living in urban New York she is still connected to the natural world. NR Magazine joins the artist in conversation.

You have a longstanding interest in nature, something which your work reflects. How did that interest start and do you think your focus has shifted over the course of your career?

I was enchanted as a child growing up in sub-tropical Miami Beach, close to the water and surrounded by trees. That initial confrontation continues to hold my mind, imagination and has perfumed my life.

You believe that all art begins with the sacred. What does that mean to you?

The word transcendent speaks to that question. What is sacred perhaps is different for each of us. That said, everyone needs to have an I-thou dialogue within, a knowledge of their boundaries when faced with life’s temptations.

You draw inspiration from world histories and folklore. Are there any in particular which are especially meaningful to you?

I love the Norse myths, over and over I seek their wisdom as well as hopes and fears. The rise and fall of family, also beautifully haunting in their telling. Then there is ‘The Iliad and The Odyssey’ that speak to us of the evolution of feeling, of love, lust, seduction, jealousy.

Naturally occurring shapes and patterns are a key theme within your work. Do you think people often overlook motifs like these in their everyday life and could the quality of their life be improved if they look the time to appreciate such patterns in nature etc?

Patterns and shapes are magical, repeating over and over in every culture.

«Repetition itself is life-affirming. The wavelength calming.»

Has the pandemic affected how you approach your art practice and if so how?

The pandemic allowed me time for many things I had set aside until I found time to explore, concentrate deeply. That time has resulted in clarity.

A Walk on The Beach is one of your largest and perhaps most well-known works. Could you tell me about the process of making this work?

The bronzes all came out of Doner studio over the course of 24 years.

«It became ritualised activity, a materialised tone poem, a saga. I carried the notes in my head and composed in my sleep.»

What does identity mean to you as an artist?

Being called an artist is only an avatar. I have many identities.

How has your experience of being a female artist changed over the course of your career and has that change been for the better?

I have always fully embraced the feminine aspect. That said, gender is a spectrum.

«We are moving in the direction of a more equitable balance for both genders and I am happy to be flowing in the river of change.»

What advice do you have for young creatives?

Be a good dog. Dogs don’t dig up other dogs’ bones.

Are you working on any projects at the moment and what plans do you have for the future?

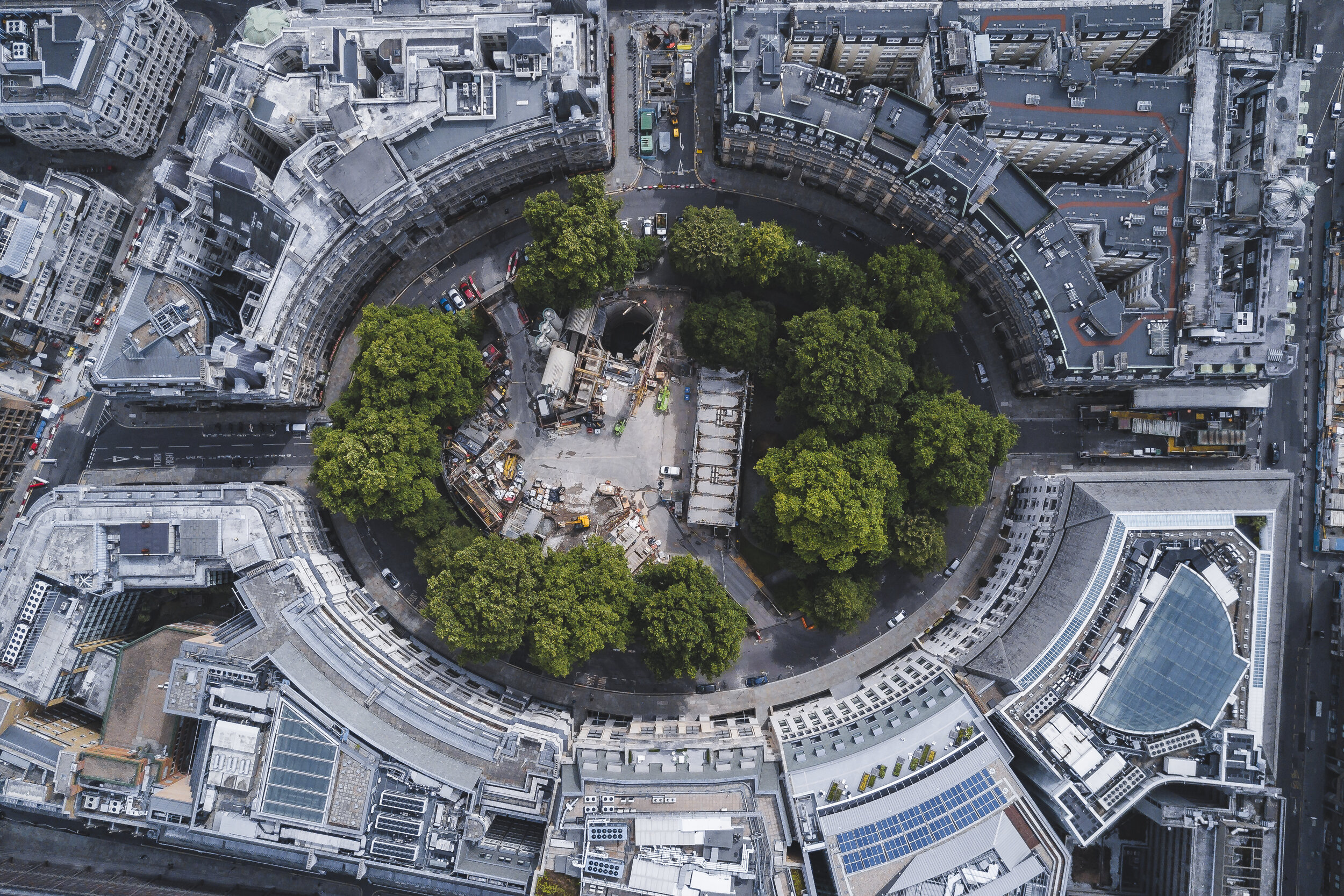

I am going to be the designated guardian of the banyan tree I grew up under in Miami Beach across the street from my childhood home. It will be declared a natural wonder very soon.

Credits

Images · MICHELE OKA-DONER

https://micheleokadoner.com/