Architectural evolution

Embarking on the architectural journey of Makoto Yamaguchi, our conversation explores the evolution of his approach across various projects, spanning commercial offices, private residences, and museums. A significant focus lies on the acclaimed “Villa / Gallery in Karuizawa,” unraveling insights into the flexibility of its spaces. Transitioning to the distinctive MONOSPINE project designed for a game production company, we delve into its unique architectural elements. Our dialogue extends to considerations for newer generations and delves into the prevalent challenges in contemporary workplaces, specifically emphasizing well-being.

Dear Makoto Yamaguchi, I’d like to begin by asking: How has your approach to architecture evolved, considering the diverse range of projects you’ve undertaken, ranging from commercial offices and private residences to museums?

My approach to design is the same regardless of the size or type of project. It’s about creating a scenery. I was originally very interested in how to create scenery.

Scenery, to me, means the same as so-called natural sceneries, which don’t seem to have any purpose. This is common to past projects, but I feel like I’m more aware of this than in my early projects.

When we mention “Villa / Gallery in Karuizawa,” the first thing that comes to mind is its recognition as the best residential project in the world in 2004. I can’t help but inquire for more details about this remarkable project. Could you elaborate on the flexibility and adaptability of the spaces within the residence? What considerations were taken into account to integrate kitchen and washroom facilities seamlessly into the concrete floor of the villa?

The clients for this project were a couple of musicians. After talking with them, we realized that the villa could be an abstract, empty space with no defined purpose. In this way, the kitchen and bathroom became no longer just places for that purpose, but places where the activities could take place. As a result, equipment was buried on the floor.

Amidst the increasing yearning to reconnect with nature, what specific elements of the local biodiversity influenced the client’s decision to select that particular location as the ideal space to build their house?

They are very good at cooking and like to cook. Before the building was built, when they entered the forest grounds, they always found edible wild vegetables growing wild and large leaves that could be used as plates. I have often seen the couple using them to create truly beautiful and delicious dishes. They enjoy discovering and using different things in a place.

Now, I would like to learn more about MONOSPINAL. Considering the project was specifically designed for a game production company, how do you perceive the current significance of video games as a social, cultural, and technological expression in contemporary society?

The name was given by a novelist who writes stories for games produced by the company. The games created by them are probably different from the video games that are generally recognized, and are characterized by their excellent story-telling. They have fans all over the world, and you can see many animations by other Japanese companies that have been influenced by the settings, lines, and scenes of their works, and you can feel the magnitude of their influence. can. We are paying attention to how these artists, who have such great influence in media culture, produce works of even higher quality.

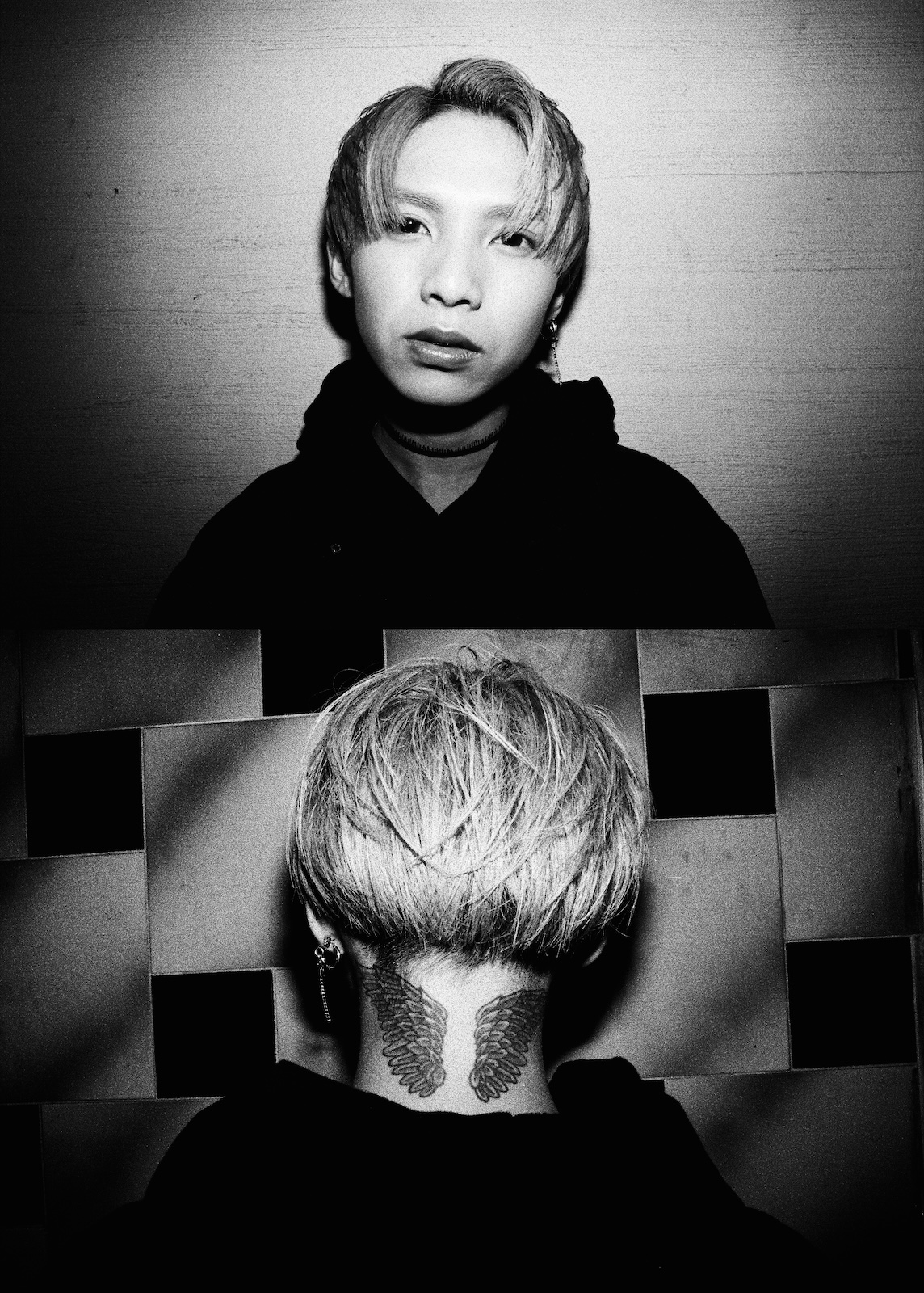

What inspirations led to the selection of the term “MONOSPINE” for the design of the company headquarters?

This word is a coined word that combines the words “monochrome” and “spine.”

The architectural element that most characterizes the space is the repeating pattern of sloping walls. How does this specific design contribute to the functionality of the new building in terms of lighting, ventilation, and acoustics?

Facing the site is an elevated railway where trains pass every 1.5 minutes on average both ways. The site is also surrounded by small-scale buildings, each with a variety of tenants. While the slanted walls enhance environmental elements of light, wind, and sound, every wall height is optimized according to the different purposes on each floor. For example, behind the third-floor walls are studios for recording the voices of game characters. They are heightened as much as possible to reduce noise from the railroad. While the walls block the views of the surroundings, they reflect natural light to bring in indirect light, maintaining the world and ambience of games during the recordings. On the fifth floor, which is vertically further from and with a lessened sense of connection to the elevated railway, the lowered walls provide a cropped view of the cluttered cityscape and the sky. With a great balance between direct and indirect lights, while steadily taking wind into the interior, the room offers a relaxing dining experience.

The slanted walls protect the interior from the external gaze, making it impossible to tell what the building is for from the outside. Not being able to see the purpose is much the same for natural landscapes. The slanted walls are made of thin, ten-centimeter-wide aluminum plates, a material of relatively familiar scale to humans. Rather than constructing a large building with large modules, we brought small-scale things together to create a bigger scale. This approach echoes the way nature is formed and grows. By adopting such a method of creation and making the building an object that does not give away information just like the natural landscape, the architectural work becomes part of a new townscape.

Among the newer generations, there is a growing acknowledgment of the vital importance of nurturing intercultural and intersocial dialogue to foster emotional connections and stimulate contemplation on various aspects of life. The communal table on the fifth floor stands out as an ideal setting for these endeavors. Could you share more insights and details about this space?

This table is where they eat lunch and sometimes dinner. For the staff, this building is more like a home where people from a wide range of age groups who share common values can gather, rather than a company. They all gather around this table, eat together, and play their favorite games (which were made by other companies). All of the top creators are fans of the games they create, and that’s why they’re here. It’s the place where people with shared values can relax, be inspired, and gain inspiration.

In the current landscape, the central challenge for workplaces is the well-being of employees, characterized by ongoing discussions about burnout and architectural deficiencies that exacerbate this concern. In response to this, how does the design specifically target the improvement of overall well-being and job satisfaction for employees involved in creative operations?

This is aimed to become a place for the highest level of creation that captivates fans worldwide and for supporting the foundation of the game production process. As almost all employees engage exclusively in creative operation, we focused mainly on providing a balance between concentration and relaxation while significantly removing the burden of operational work. We strived to achieve them by introducing slanted walls that characterize the exterior and a system to control all facilities, including security, with tablets.

We placed the areas mainly used by visitors on the lower floors, while the level of privacy and confidentiality increase as the levels get higher. On the second and third floors that face the elevated railroad tracks, we placed programs that require isolation from the outside such as the theater and the studios. The slanted walls are higher on the lower stories surrounded by existing buildings, whereas they are lower on the upper stories offering more sense of openness.

The landscape design, interior and exterior finishes, and fixtures all incorporate the style of the game world (the period and region in which the game is set, characters, items, etc.) created by the company as metaphors, which can be deciphered if you are familiar with the game. In other words, the headquarters building itself is made of the game.

Credits

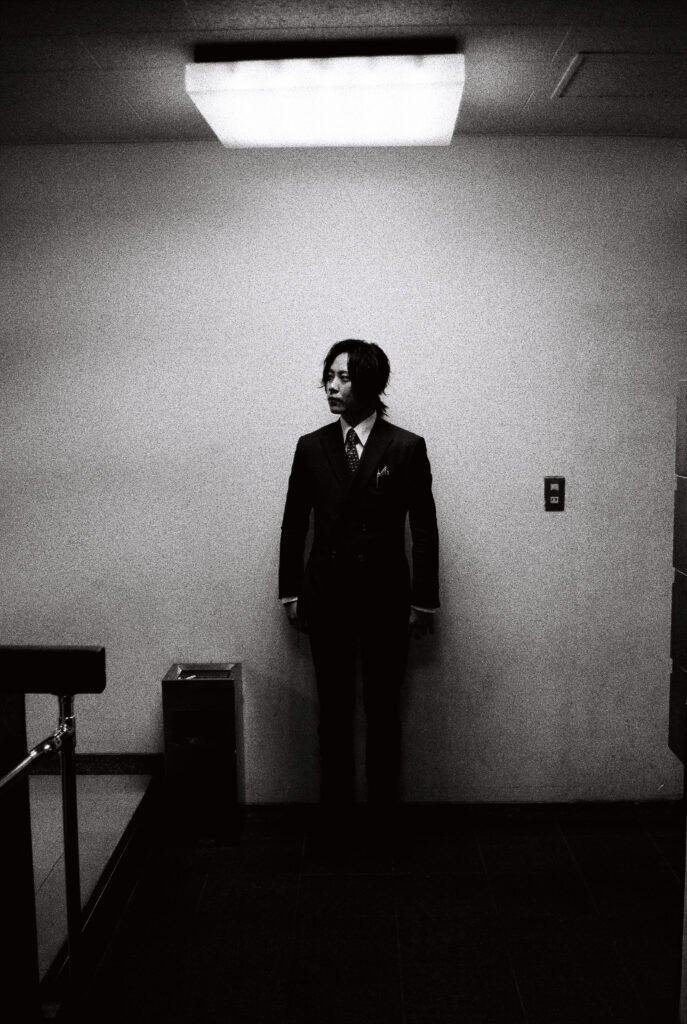

- VILLA / GALLERY, Karuizawa, 2003. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.

- OGGI Apartment Building, Japan, 2013. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.

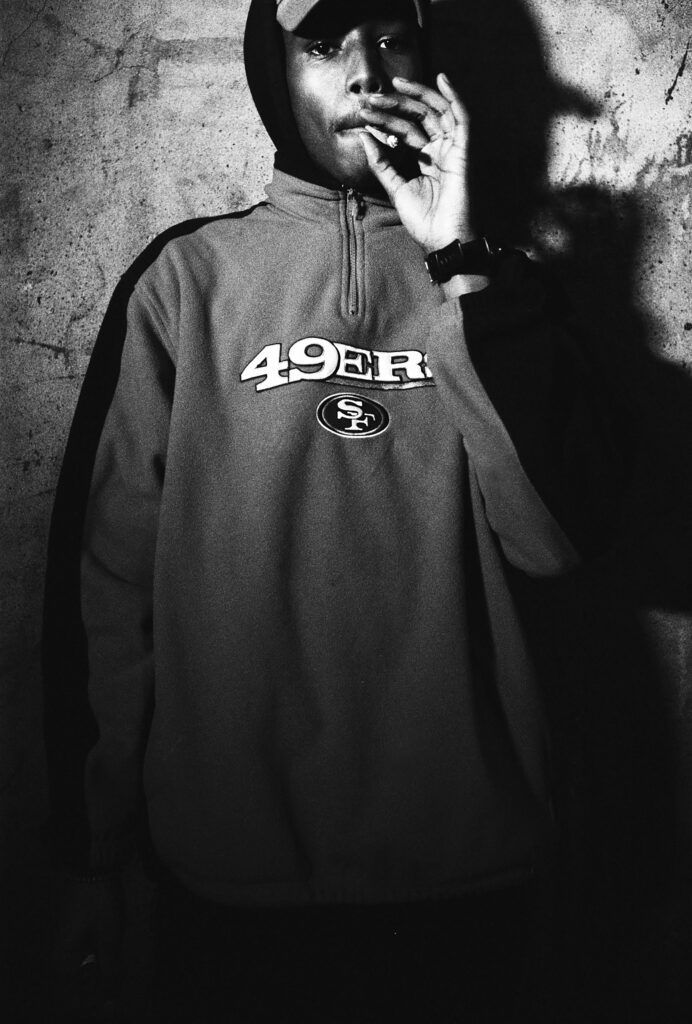

- VILLA / GALLERY, Karuizawa, 2003. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.

- VILLA / GALLERY, Karuizawa, 2003. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.

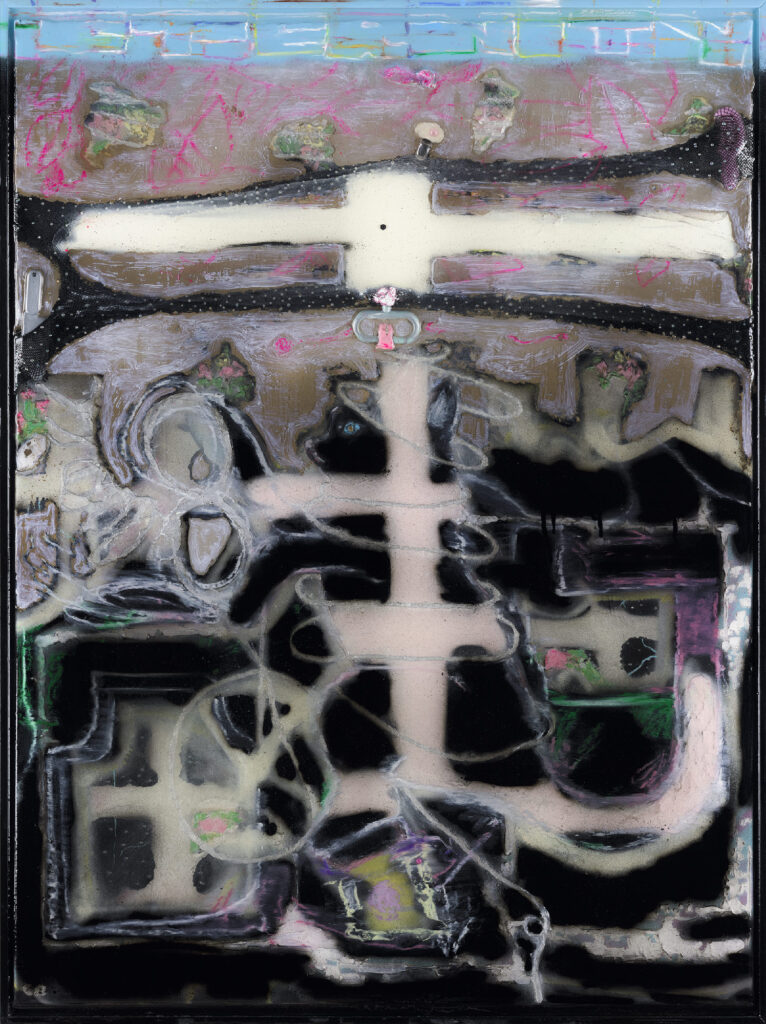

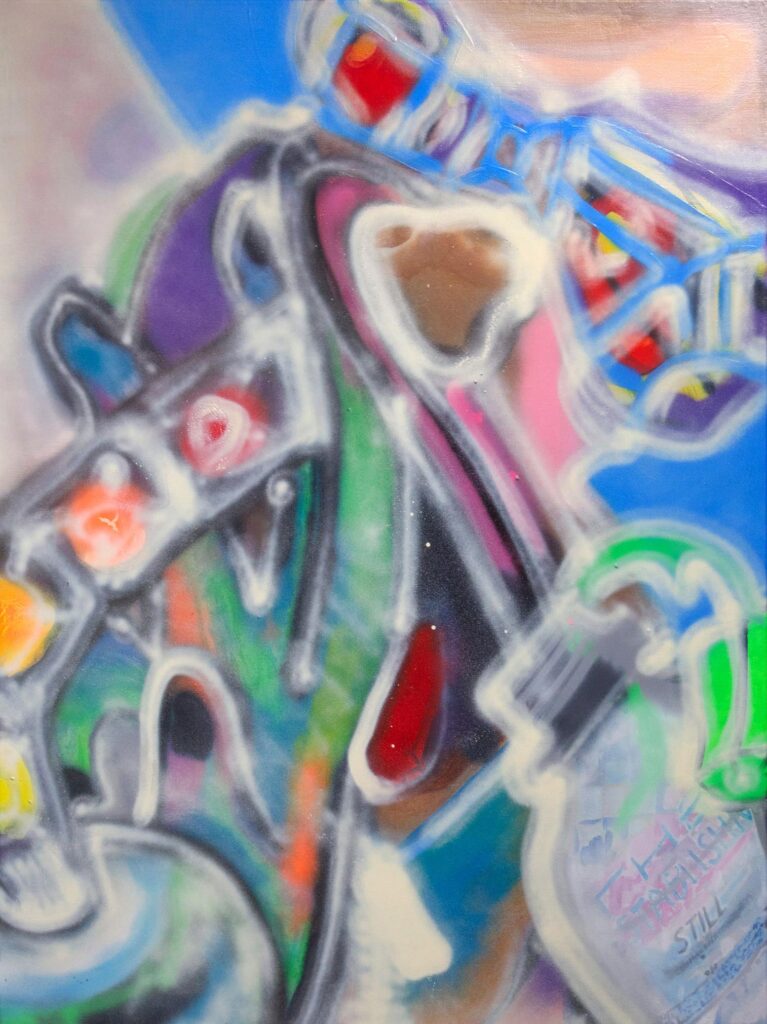

- MONOSPINAL, Tokyo, 2023. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.

- MONOSPINAL, Tokyo, 2023. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.

- MONOSPINAL, Tokyo, 2023. Makoto Yamaguchi Design. Photography by Koichi Torimura.