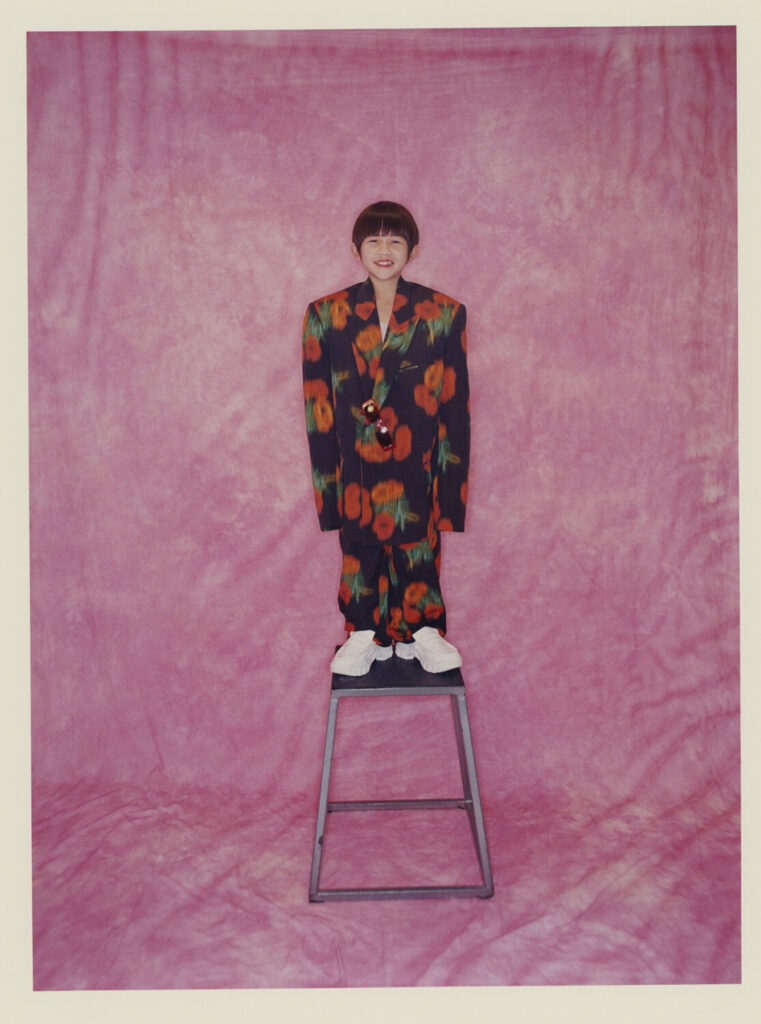

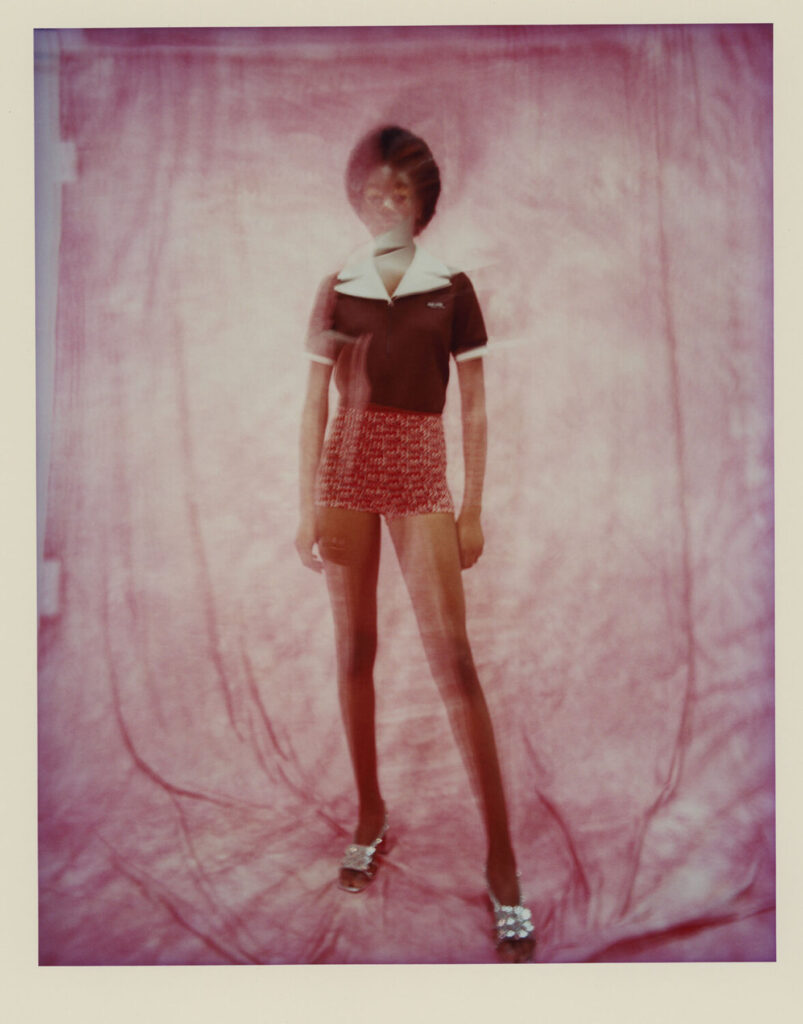

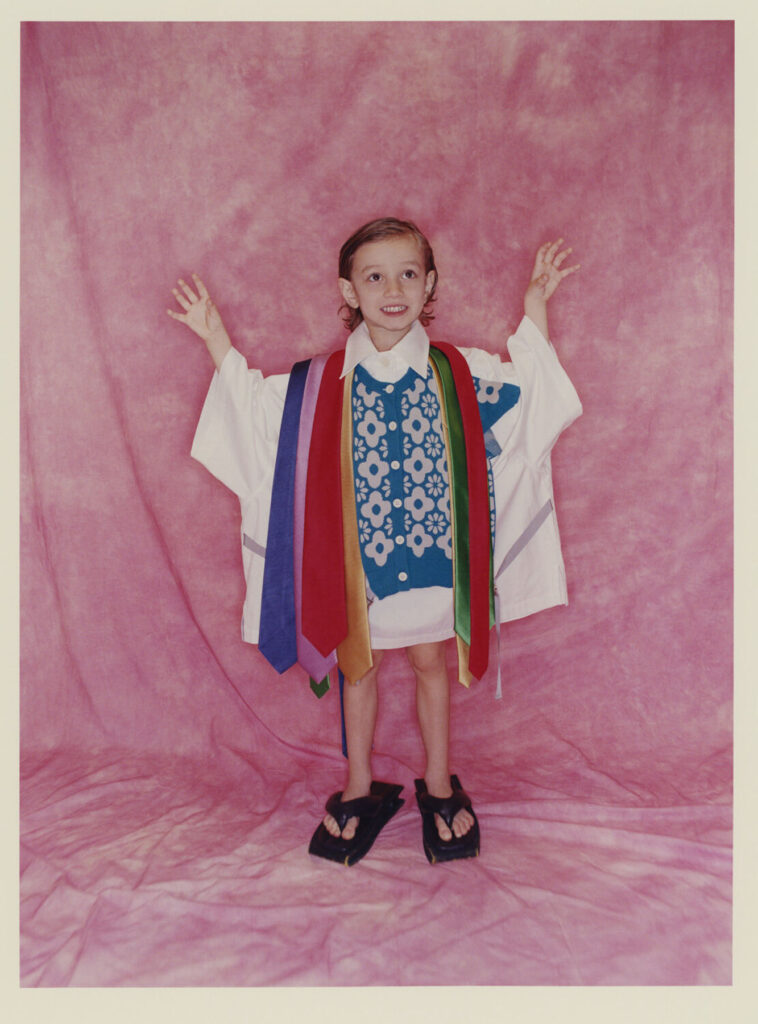

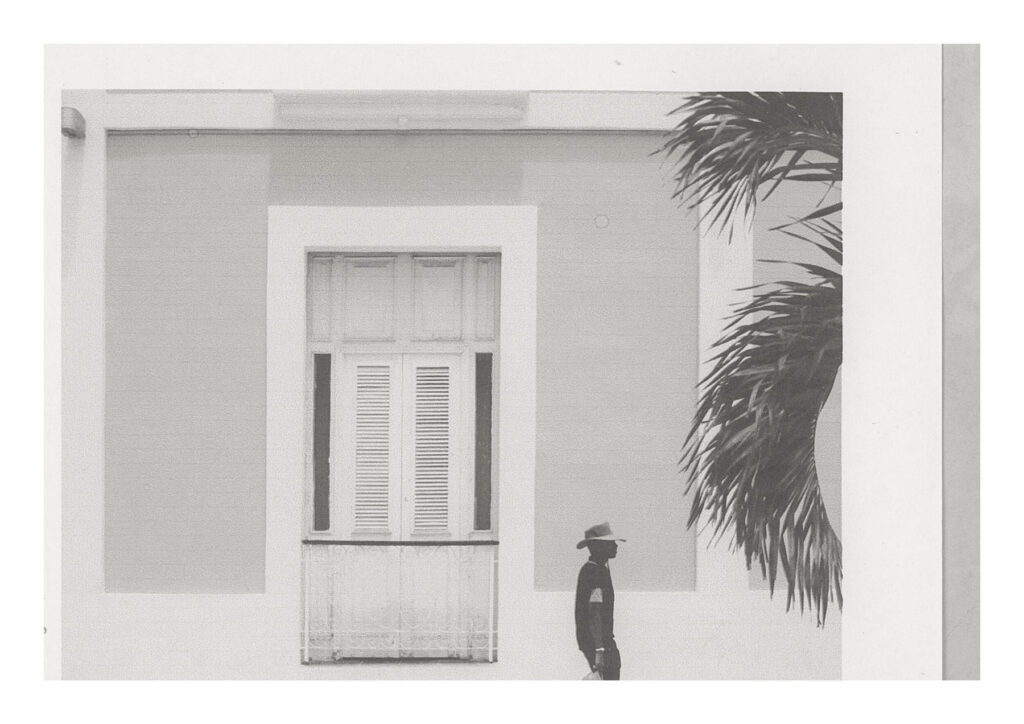

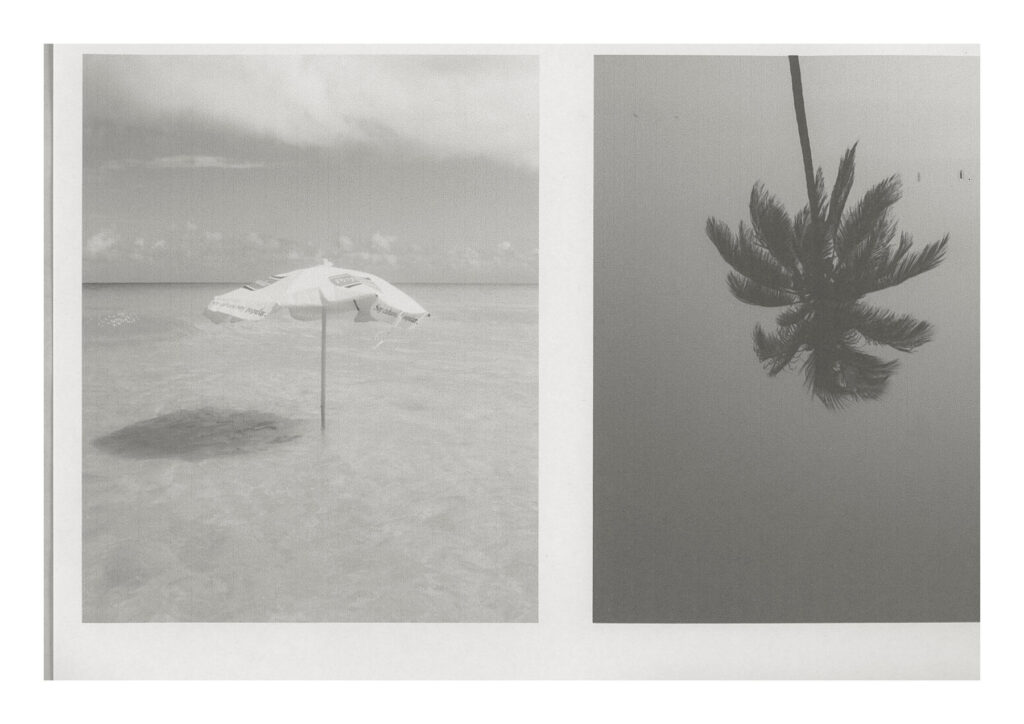

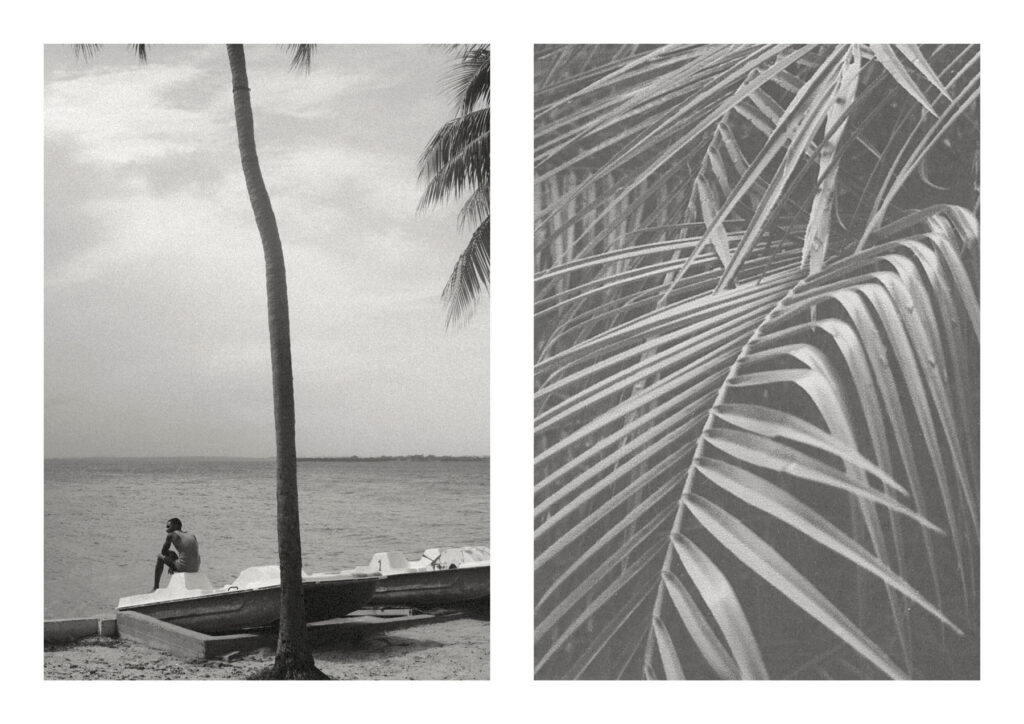

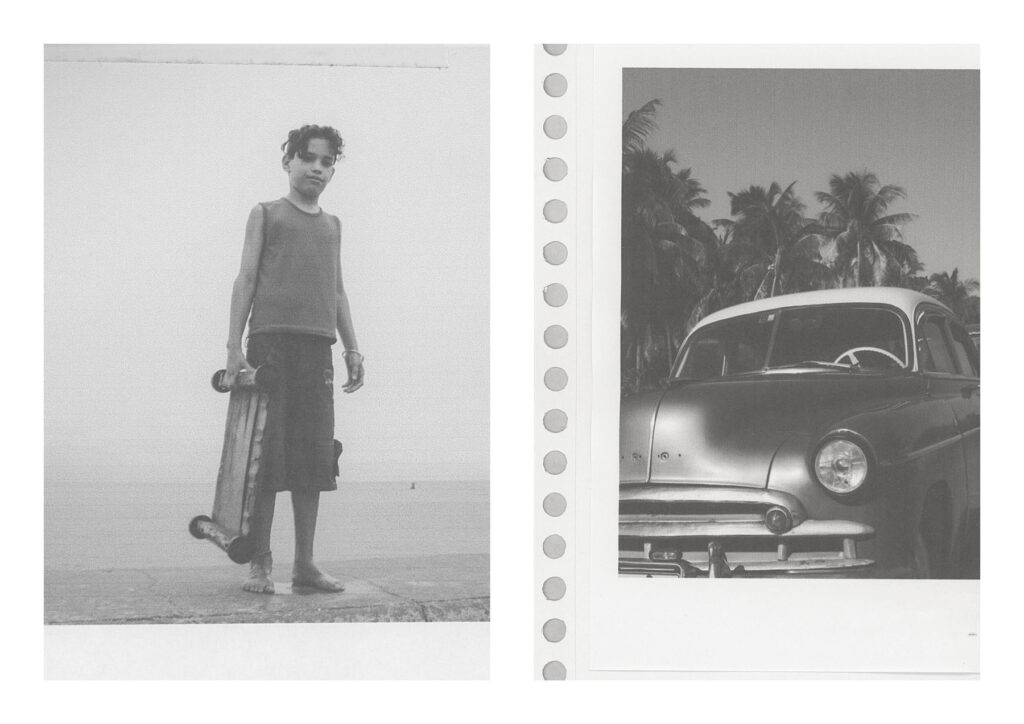

Blackhaine’ poetic yet brutal investigation of reality with unique soundscapes, choreography and cinematographic visuals.

Tom Heyes, also known by his artistic moniker Blackhaine is a rapper, poet and choreographer from Lancashire, UK. Known by many for his projects with Kanye West (Donda 1 and 2) and more, the multidisciplinary artist has forged for himself a solid path, establishing his own unique artistry. Chicago drill, industrial, ambient, experimental hip hop are some of the genres combined within Heyes’ unique soundscapes. With producer Rainy Miller, Heyes worked on delivering visceral releases first Armour, then And Salford Falls Apart. Released in June 2022, Armour II follows the trail of the two earlier bleak releases, perhaps an ending, nonetheless part of the bigger journey the audience embarks on when listening to Heyes. With tracks featuring the likes of Blood Orange, Iceboy Violet, Moseley, Richie Culver and Space Africa, Heyes is also giving space for other artists to enter his universe. Re-contextualising his anger, Heyes delivers poetic yet brutal narratives which juxtaposed with cinematographic visuals, immerse the viewer into Heyes’ inner world. Choreography plays a pivotal part in his practice as he continues to investigate reality.

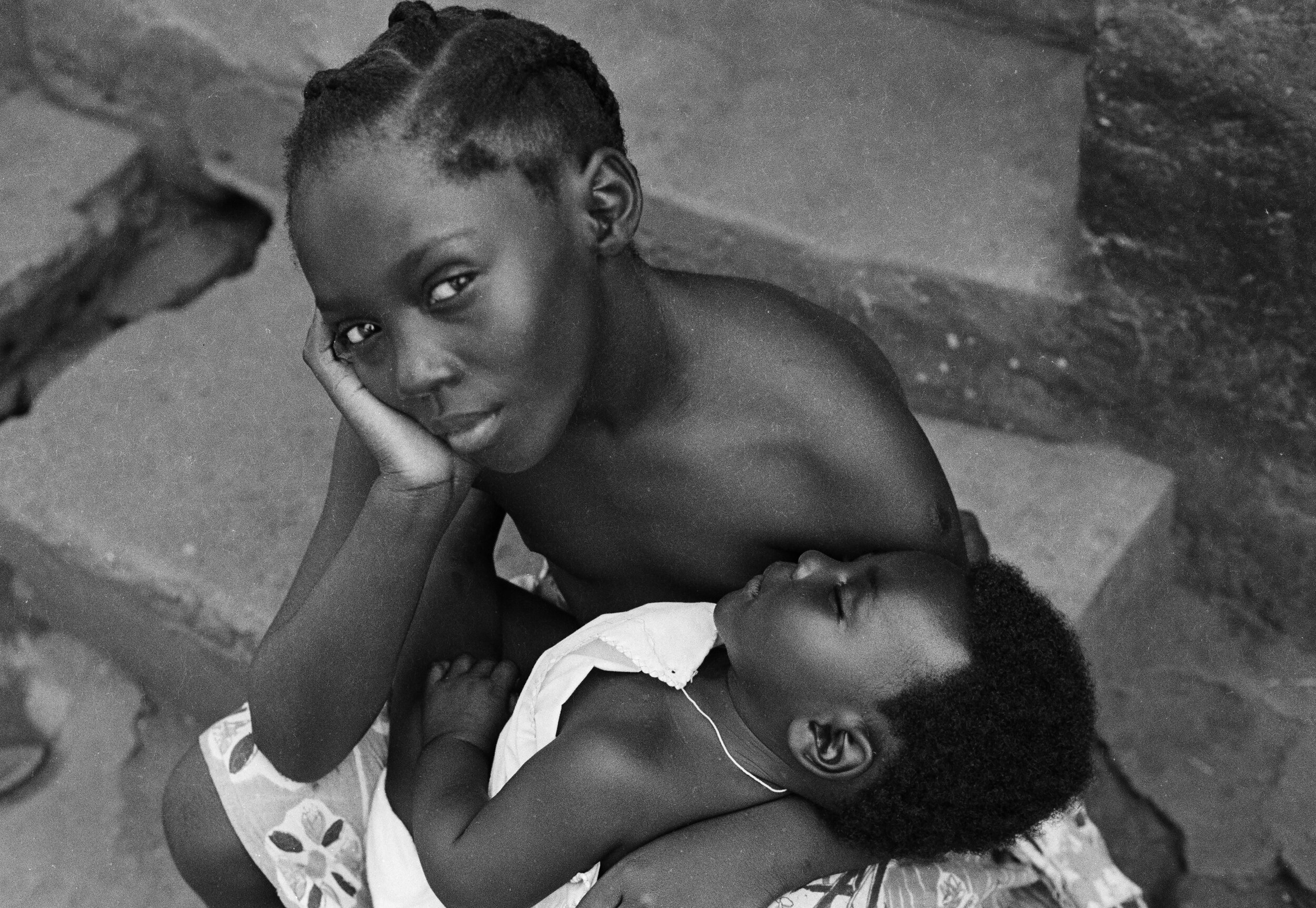

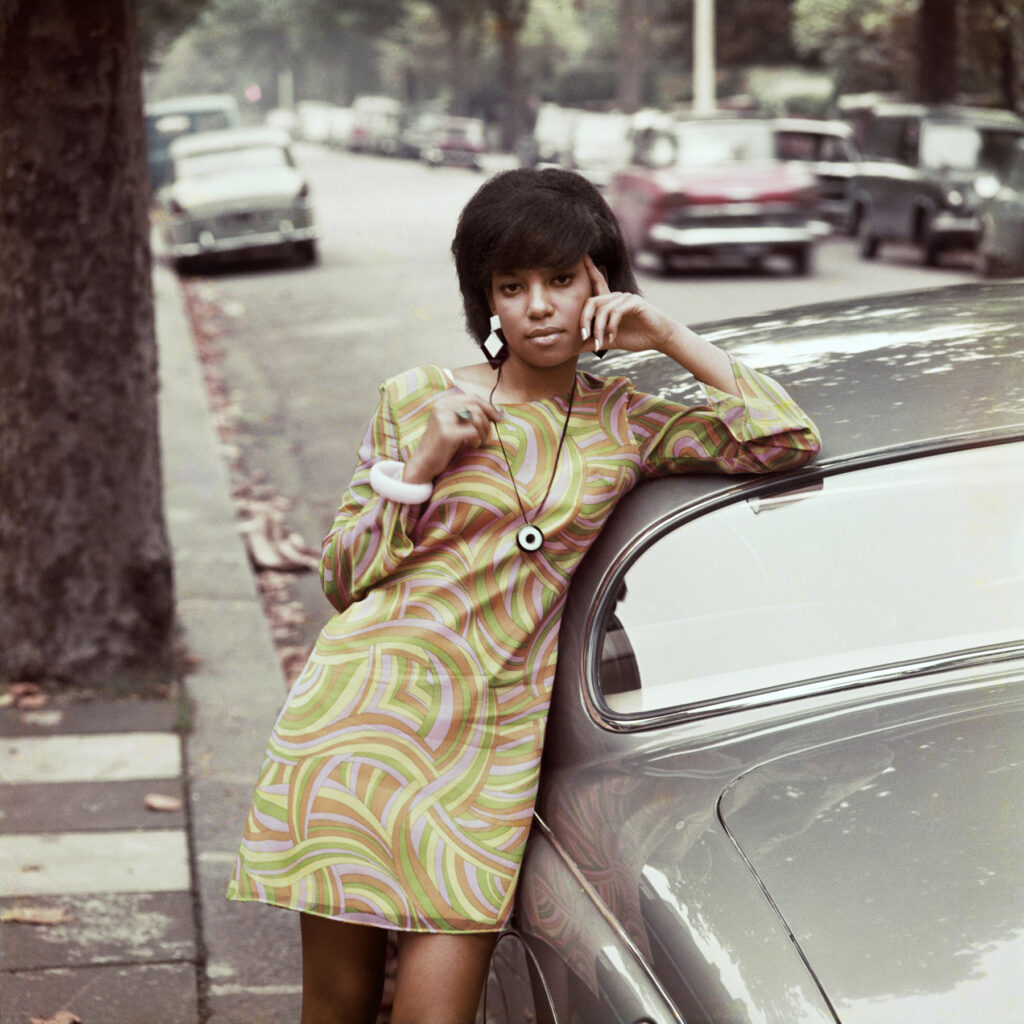

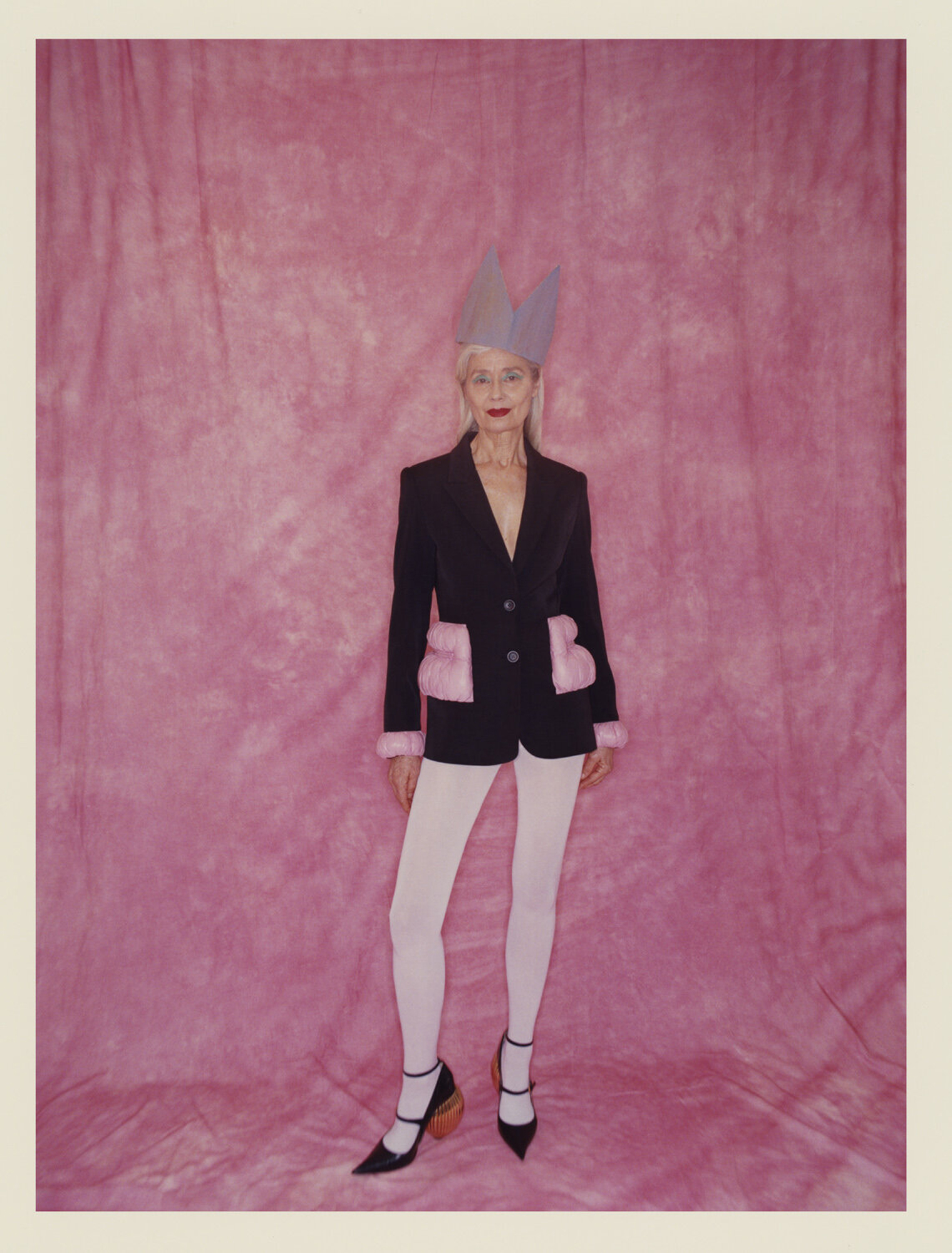

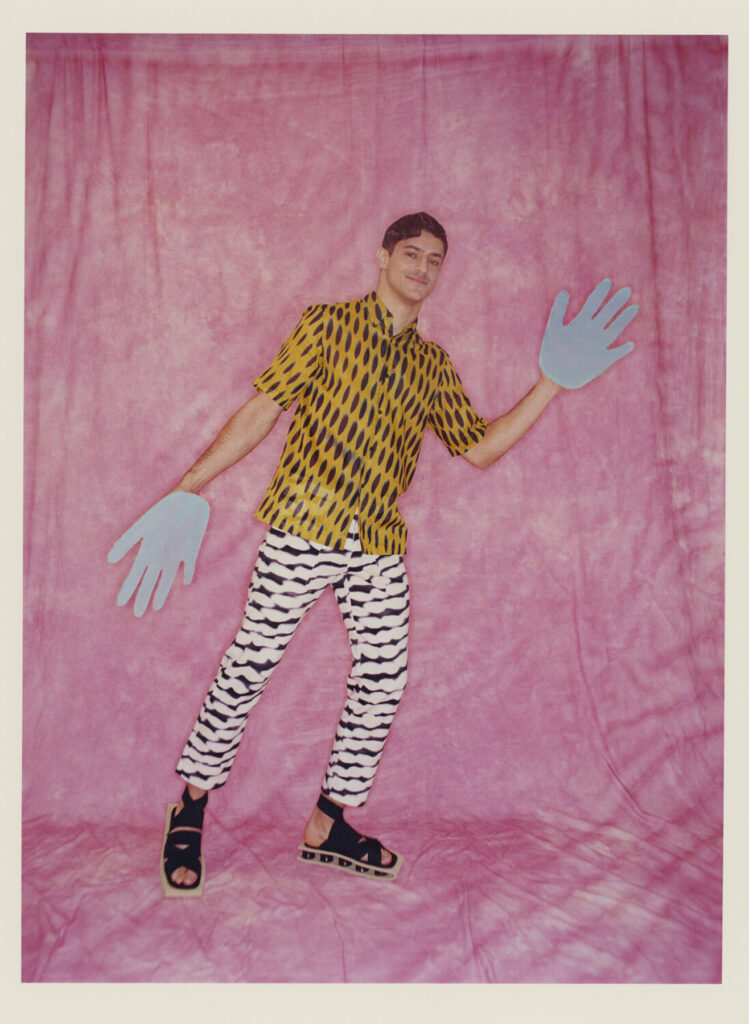

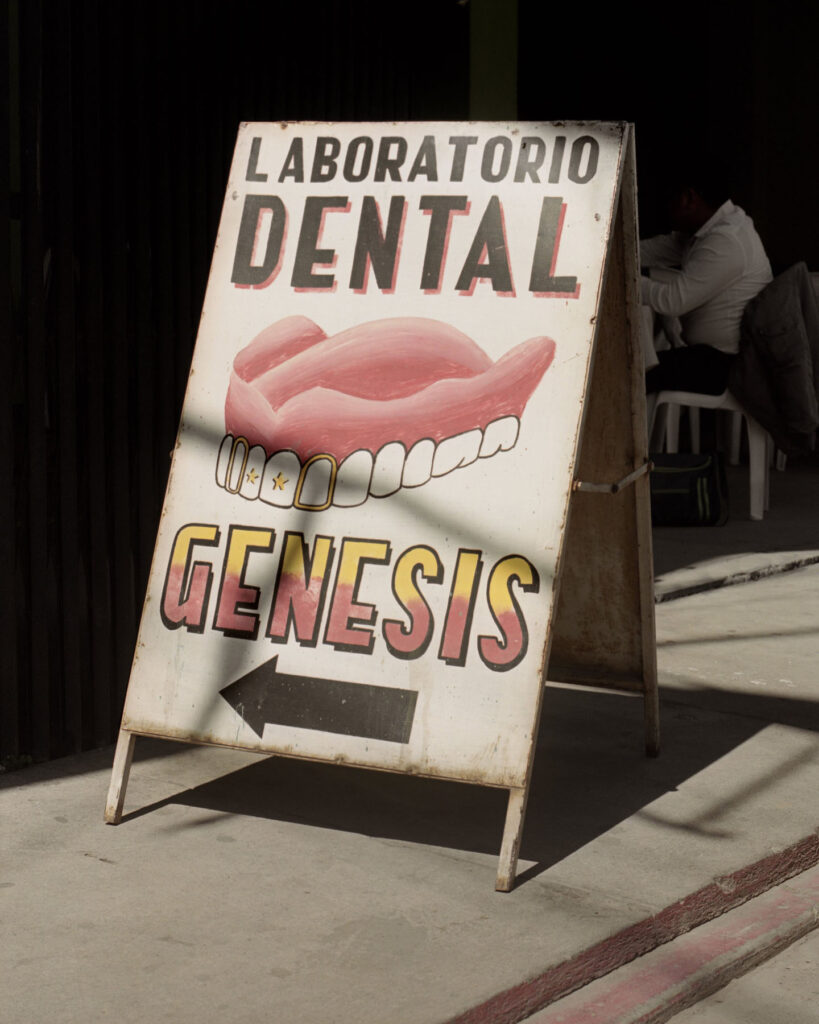

Here photographed in London by Berlin-based photographer Joseph Kadow, we witness an artist in his element, creating as he breathes, once again narrating a story of his own. Heyes talks through his genesis, the process and inspirations behind his body of work, spanning across choreography, music, spatial design.

When and how did you start?

I’ve been interested in film since I was young, from there I started to learn about sound and movement.

I held an interest in art and between jobs managed to make some decent pieces and work on other’s people’s visions for quick cash.

During the pandemic I started creating my own film and sound pieces, releasing my first track Moors – and some film projects I created + a project named Armour made in collaboration with Rainy.

Blackhaine is a node to the French cult classic La Haine on violence and inequality in the suburbs of Paris. You come from Lancashire, UK. How has the landscape of living on the margins and of social and regional inequality, influenced your practice?

I’ve always felt detached from the current sound, I think being in isolated yet restricted places; Blackpool, Blackburn ect you have no expectations of being accepted by a mainstream crowd. This gives room for experimentation.

I read Passing Time by Michel Butor recently and was inspired by the detail he created in his idealised Manchester, taking monuments/icons of the city and glitching them. It’s what I had been doing to Lancashire.

Darker versions of locations feature in my work such as the M6 or the Moors, Rawtape and I used scans of Blackburn high street and Blackpool tower to create a world in Hotel. In my writing I talked about experiences here in tracks like Saddleworth or Stained Materials.

“Using ultra realistic scenes that verge on boredom and taping a bleak-psychedelic lens to the camera was a huge influence in building the Blackhaine world.”

How is Manchester’s cultural environment and how is it influencing your writing?

The environment is too self contained, and concerned with itself and it’s history when what we should be doing is looking outwards and ahead. There’s not much interesting happening here at the moment because there’s too many people left over from the 10s.

The city hasn’t impacted my writing aside from being influenced by Joy Division.

Drill, experimental hip-hop, ambient, industrial and electronic are genres part of your soundscapes. Are you more influenced by Chicago Drill or Brooklyn Drill? What are some of your musical influences?

I’ve been into Chicago Drill since the start, however it was UK Drill that got me into writing.

I would say the industrial sound was an influence but the earlier post-punk side, not as much what’s happening there now.

At the moment I’ve been listening to Carti, Zone 2 and some more experimental stuff whilst I

work on my album.

First Armour, then And Salford Falls Apart. How does Armour II succeed to these?

There’s the obvious narrative link.

“Sonically I used a softer palette and wrote about a contracted hate that became inverted by gradual unease and paranoia.”

I put more focus on working with melody and traditional songwriting before my album.

Armour II is death of Blackhaine before a burial.

How do you usually work with producer and composer Rainy Miller?

I write alone and with the ideas Rainy sent, before we sent parts back and forth online but with Armour II we started renting a studio together with Space Afrika so we could spend time in there.

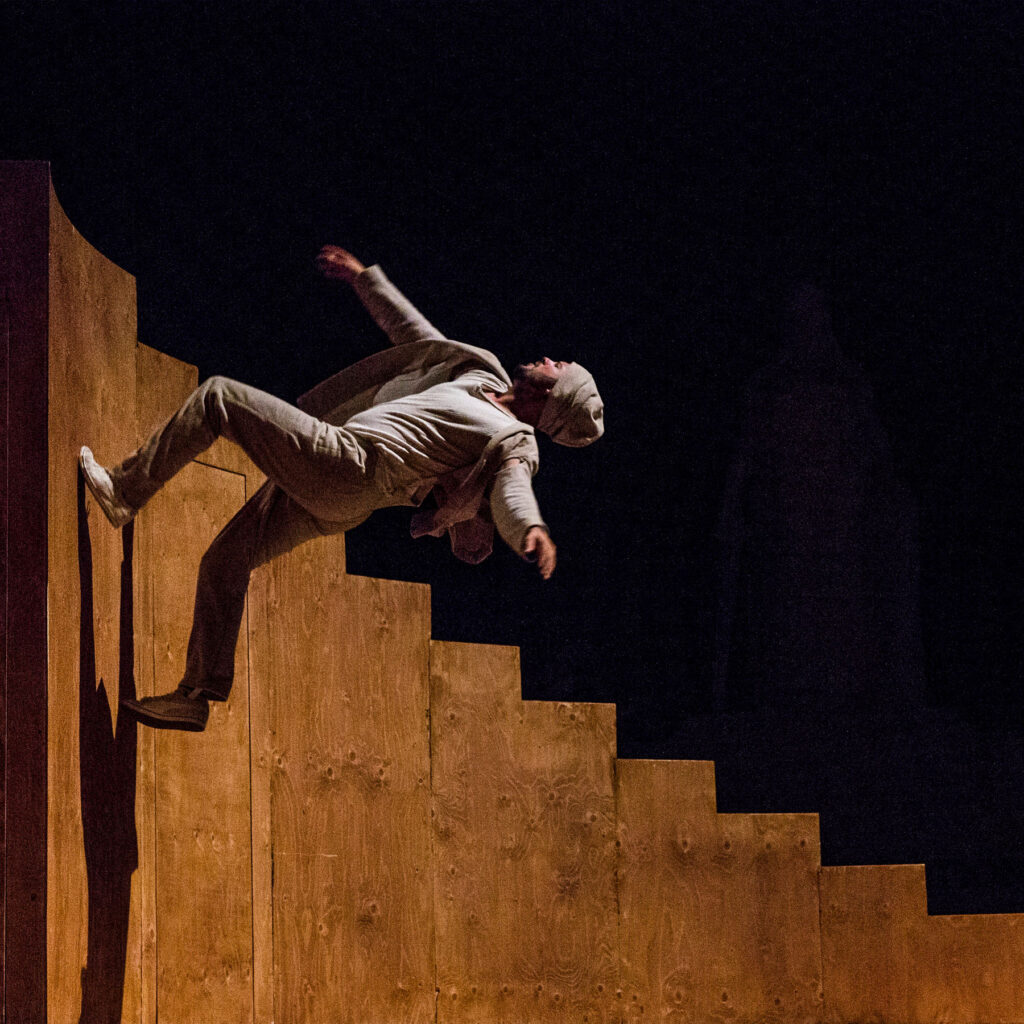

You showcase a unique choreography rooting itself from an extreme creative process. Could you talk more about this? Who are some of your favourite choreographers or a contemporary dance piece that moves you?

My choreographic style is rooted in perversion and deconstruction of traditional technique, not an anti-technical statement but a separatist practice. I utilise improvisation and sculptural design in the process instead of overt unison structure, and when the work features this form of choreography it’s effect is exhaustion and depletion to the body/mind of the performer, allowing accessibility into new realms.

Choreography a subliminal art, the same modes I work in with writing and sound. The narrative structure of Armour II leading from my previous work is a context for myself and the listener however it is no anchor, this is world building with intent to suture between and deconstruct inside of reality, whilst considering base reality and boredom, hence the exhaustive features within my work. I was initially more interested in examples of choreography I could find in day to day life, the way the bodies on top deck moved whilst the bus turned a corner, a drunk body or the result of excessive strain on specific muscle in the arm.

Pre-tense is naturally prevalent in choreography.

“I think embodiment kills honest movement to a degree and my service as an artist is to

investigate reality within abstract art.”

My favourite choreographer is Tatsumi Hijikata, I developed my practice whilst watching Butoh videos and abusing drugs in my room and hotel apartments, around the time of the Manchester spice epidemic.

I’m watching a lot Gisèle Vienne, Louise Vanneste, studying Sun Ra’s relationship with dance and sound. I would say Philippe Grandrieux’s use of movement in his work as well as Steve McQueen’s in Shame has impacted my choreography also.

How do you envision the live shows and how do you feel about finally being able to perform gigs in front of physical crowds? Visceral stage performances, atmospheric, intimate and raw sets are some of the comments from people who have already been to your live shows. How do you want the listening experience to be? How do you approach the spatial design situation too?

It’s great, during the first tour I worked intensively with spatial and atmospheric design.

“I want every show to be different, switching between shows of an exhaustive release for the audience and myself and shows that focus more on subtleties with performance and design.”

I work with heat and scent a lot, as well disorientation from lighting source. Playing drill between harsh noise/drone, these are elements that I work with impulsively, so I live edit the lighting, track list and other utilities whilst on stage with my team.

I don’t believe that playing all the hits equals satisfaction for the audience I want to create a journey for people to follow, experiencing the themes within my work physically and mentally having to endure moments discomfort before being allowed to feel gratification by silence or melody.

The feedback I have had has been great, everyone I have spoke too has had a different experience I’m grateful for everyone who comes to a Blackhaine show to experience. Thank you.

How did your collaboration with Blood Orange and Icebox Violet for ‘Prayer’ unfold?

I had the ideas of the track for a while, I was sent a rough loop from Rainy that triggered something in me. I kept revisiting the narrative and developing this film scene I had in mind, even down to the shots I wanted in the film that was made.

In And Salford Falls Apart and previous releases I didn’t work with other voices. A design focus of Armour II was to curate outside artists and let them inhabit my narrative, even to allow this to influence and lead me at times. I wrote to Iceboy Violet and Blood Orange to ask them to feature on the track and they delivered these beautiful verses back.

The theme of this issue is IN OUR WORLD, in your mind, what does England mean to you?

“Apathy.”

Now that Armour II is out for everyone to experience, what is next for you?

I am building an infrastructure named Hain. This will act as a container for future work/curation and ideas beyond Blackhaine and an investment in culture.

Team

Talent · Tom Heyes (Blackhaine)

Photography · Joseph Kadow

Creative Direction · Jade Removille

Fashion · Azazel

Grooming · Linus Johansson

Photography Assistant · Masamba Ceesay

Fashion Assistant · Olivia Abadian