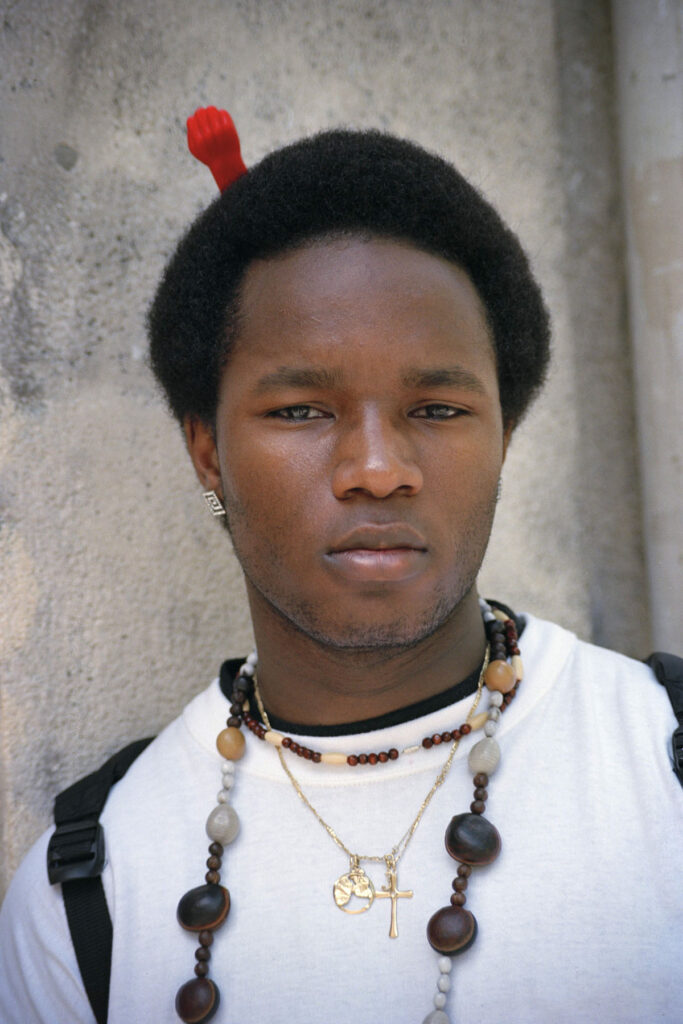

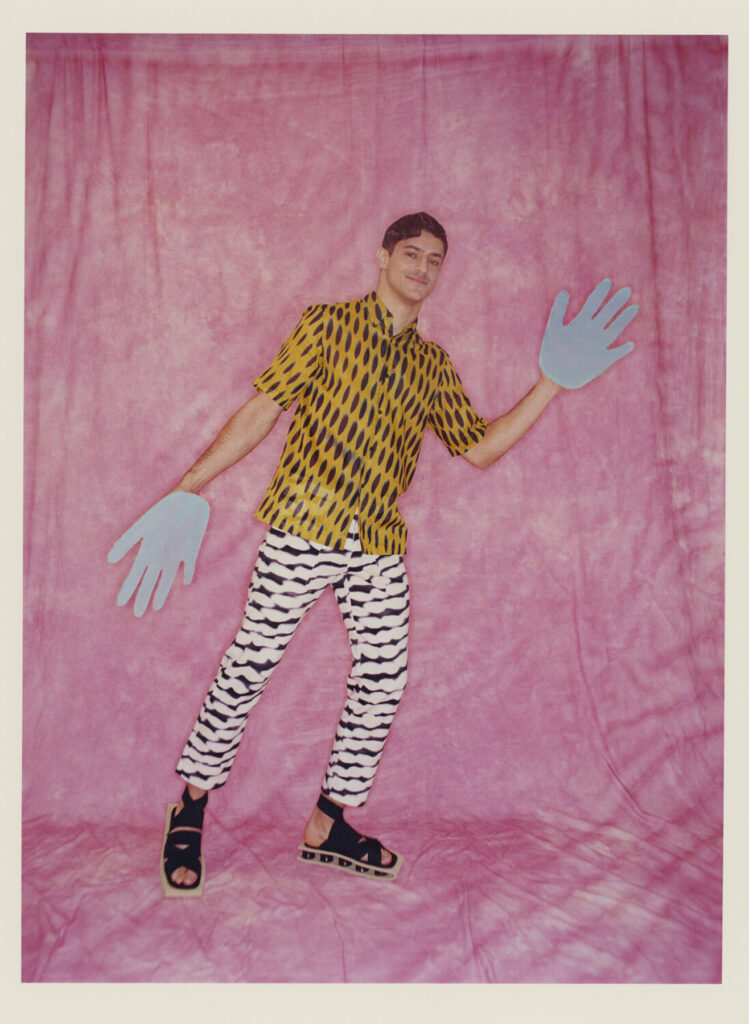

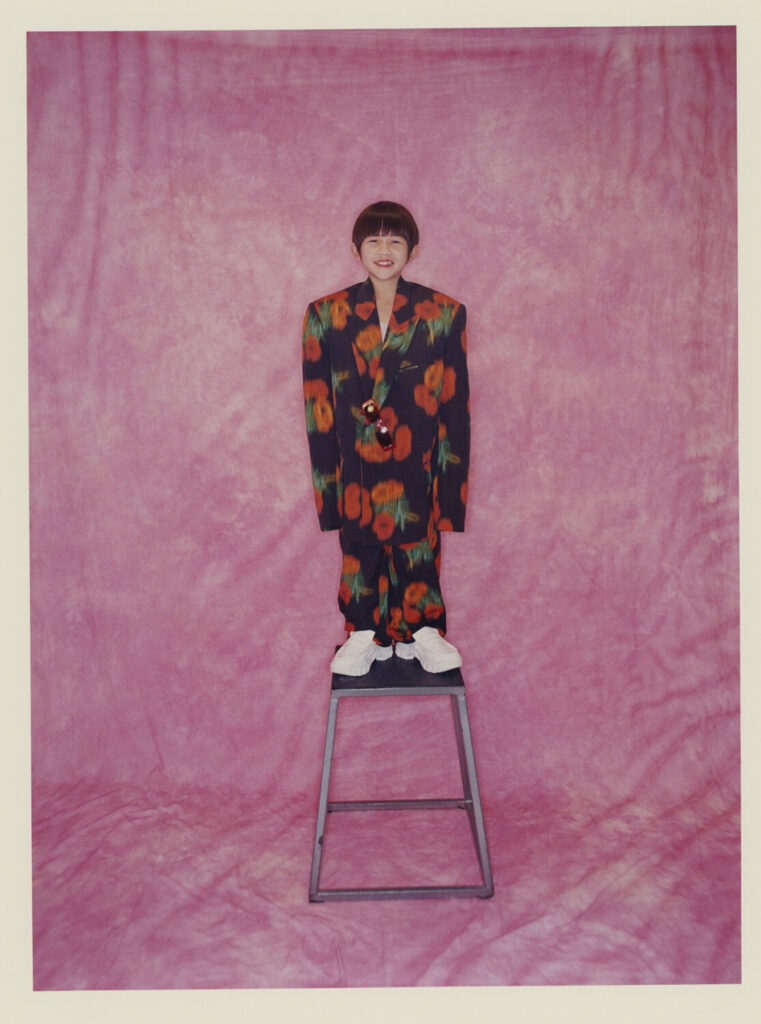

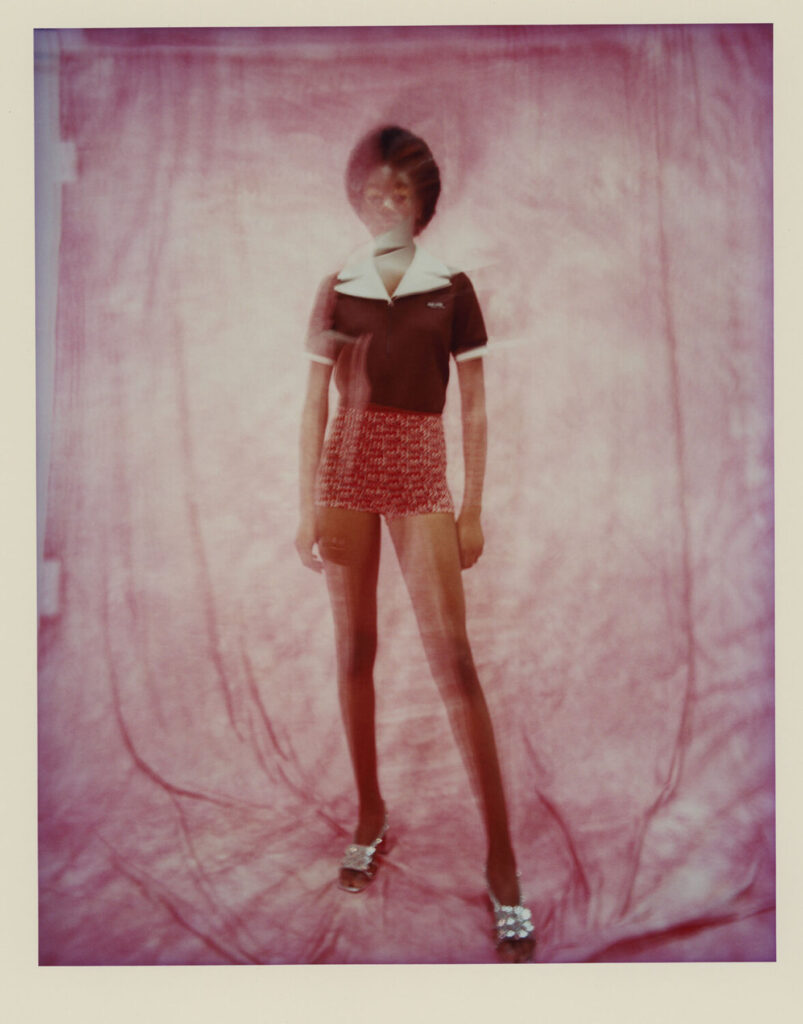

Through Clip’s looking glass

She loves music and making friends. Clip’s IG bio could very well encapsulate her attitude. But that would mean remaining on the surface level of what the NYC rapper and artist is all about. NR interviewed her back in (month) to learn more about her world. into her world —after all, what better guide could we ask for, if not herself?

I’ve seen a lot of media coverage, web exposure, and you just teased lots of big and very interesting collaborations. You came firing straight out the gate.

Oh, honestly, I’m really thankful for how fast things are evolving and how packed my year has been so far, but it’s kind of been weird to adjust because there’s been so many life changes. We kind of had to find the best way to navigate through all the madness. Luckily I have my team, and the people who are close to me –they really make it easier. But I still sometimes don’t really know how to navigate everything..I just try to make it work!

How’s all of this, a new team, more exposure, a bigger community, impacting you?

I still try to just do my thing, but at the same time I’m obviously trying to be more of an artist, really honing in on my craft without changing too much of myself. It’s the same energy I’m putting in, I guess only in a more professional way –less like a girl with just her phone doing whatever, and more structured.

Less DIY?

That’s the perfect word for it. I was so DIY for so long, and I still kind of am. Only now, I have amazing help around me!

It feels like your relationship with your fans and the people that your music speaks to is very important in what you do.

It’s everything.

Even the way that you interact with them, It makes you think that it somehow translates in your process. What sparks you?

Tying back to you mentioning communities, I always was longing to be a part of something growing up, and I found that through music. It makes me feel so privileged. I really just want to own that and make sure everyone that supports me feels as seen as I do right now. It’s something I hold close and try to remember everyday: making everyone feel like they’re accepted, because life is just crazy and we should try to make things better for everyone, in our small ways –But I’m getting a bit sidetracked. Back to my process; I like to say that I don’t really have one –It’s like the beauty behind the madness: Whatever comes to me, comes to me in the moment. I try not to overthink things, because overthinking is my biggest enemy, something I’ve always struggled with. Sometimes my friends will say that when I create, it’s like I’ve been possessed by a music entity or whatever. My old music really used to reflect a lot of emotions and situations that I was experiencing at the time because my life was just so crazy, changing so fast –I just used my music as a way of coping. Nowadays I’m trying to have more fun with everything. As I started going out more to parties I was like “okay, I would love to turn up to my shit in a club.” But I couldn’t! I only had sad songs out! [laughs] So lately, I have been trying to make more, let’s say, happier club bangers.

Things around you and what your experience is changing. The recipe might be seemingly changing, but it really isn’t, right?

Exactly! This is myself, and my music reflects that just, naturally, you know?

I read about how it’s very important for you to be a mirror for other people to see themselves in. However, your music is very personal and intimate. There’s this sort of contradiction, but you still manage to create something that feels open to the listener. They can project their own meanings onto it while still enjoying it. I wanted to ask you about this, but I think you’ve already answered it in a way.

It’s literally just like that. So yeah, that’s a cool and beautiful way of putting it!

You know, I was trying to find ways to pinpoint and define your sound, but somehow it eludes me. One word I would use to describe it is ‘cool.’ But ‘cool’ is a very elusive term. You’ve been associated with the fashion world, magazines, runways —all things that exude cool. So now, I wanted to ask you, since you describe things very personally, what would be your definition of what coolness is today?

That’s a good question. I think coolness is…owning it, your raw inner self. I like people that are vulnerable and are afraid to show the world who they are, but they still risk it and express themselves. The coolest people that I know are so real to the point where it might even be detrimental for them. But that’s what makes it cool, you can’t really replicate those things. And maybe that’s kind of a cliche, but I think not being an asshole is also very cool.

Do you have plans moving forward to further build on your personal brand of coolness, maybe reinforce your presence in different mediums other than music?

[Laughs] Anytime I used to get asked this, I would be like “Oh, you know, I’m just floating, I don’t know my plans.” But now I finally have a very precise idea about it! I want to be the face for people like me, that’s the masterplan. And, obviously, music is my priority. I love music, that’s my everything. I have this quote I always use “Music is why hearts have beats.” Music really is my life, and I never want to lose sight of that, but also I don’t want to box myself in it. I want to keep experimenting with different mediums, especially visual, and continue to show people like me that If I can do it, then you can too, because I’m literally the most normal person ever.

And what are some hidden references or elements that might have influenced your music, your overall artistic expression –something that we couldn’t pinpoint just by listening to your music, but that is there and embedded in what you do?

There’s a whole grunge era of me growing up in middle and high school that played a big part in shaping who I am. Everyone was kind of emo, but I really identify as a grunge girl. I am maybe still living in that era, you can feel it in my music. I loved alternative, experimental, sad boy music –Yung Lean, Lil Peep, Drain Gang. I was a little weirdo in class, listening to bands like The Neighborhood, Title Fight. Emotion is a big factor in everything I do. I think it’s cool to feel so intensely because a lot of people seem like walking zombies with no emotions, just going through the motions of life –I call them NPCs. I feel bad for those people who aren’t living life the way they want to. But getting back on track, the grunge era, rock, emo, and fashion all influence me. Growing up, my parents never really got me clothes because they believed school wasn’t a fashion show, going all the time like “all you need is like the essentials.” They were also conservative Jamaicans, so I wasn’t allowed to express myself the way I wanted. Once I was free from those restraints, it felt really good to be myself, and clothes played a big part in that. The whole fashion world is a big inspiration for me, and while it might not be directly felt in my music, it works hand in hand with it. And then again, now I’m walking runways and shit all over the world, you know?

How does that feel?

Pretty fucking cool! [laughs]

Being able to not only express yourself through clothes and music but also fully embrace your personality while being a professional adds a different dimension. The references you mentioned, such as Yung Lean or Drain Gang, are all artists who took subcultural and aesthetic elements and made them their own. They repurposed these elements, which is something you do as well; You are part of a new generation of artists that are both subcultural and have some mainstream elements in how they present themselves on the web. You have your own niche and audience, while rapidly moving up. This is something I think a lot about, and you are living it in a way —So, I wanted to ask you: Do you think that the way underground and mainstream used to be very separate entities is now changing? Are they colliding, or do you still think there’s a distinction between them?

People have their various opinions on this topic, mine is that the meaning of the term “underground” definitely has changed as a whole, especially after COVID, a period where a lot more people just started trying to make music, alone in their homes with nothing to do, just creating. I feel like that whole moment really shifted the underground as a whole and now it’s more saturated, but not necessarily in a bad way. On the internet, the underground is becoming the modern day mainstream, which is really cool. Maybe I’m biased because I’m so in the scene, but most of the people I know are not listening to the radio, they’re going on SoundCloud. They listen to their friends, they discover their favorite artists on Instagram, or Reddit. There’s a lot of artists that are maybe not having real commercial success, yet, but they’re getting a lot of streams, and they’re doing well, they have a proper fan base! Also, there used to be a lot of negativity in the underground, but everything now is just so broad, and so many people are just having fun with it. I’m meeting new friends because we’re doing shows together, going to parties together. Everything became really wholesome. We can breathe, relax.

Since there are now more platforms and more space for everyone, as you said, people are starting to let go of, perhaps, jealousy over a space they feel the need to protect.

Exactly. And it made everything less toxic because of that.

And how do you feel about collaboration? It seems like you are open to it, but also very selective. That’s what I’m getting from how you’re talking. Your music is very personal, and your relationship with your fans is personal too.

I think that my opinion is never gonna change on this, ever. And I’m satisfied with that. But, like you said, everything I do is extremely personal to me. So, it’s like, you can’t just give your baby to a random babysitter; you have to get to know them and find the right fit and vibe. That’s how I see it. If I do a collab, it’s because it was genuine. It wasn’t planned, it wasn’t for money. Even if I was down to my last cent, I would never sell a feature like that. I feel like I’m selling myself short, giving away a part of me, selling out. Everything I do has to have meaning; it has to be personal and authentic. I tie that in with collaborations. I’m not opposed to them, obviously—I have some out, and some more on the way. It just has to make sense and be with the right people. Not that anyone is the wrong person or doesn’t make sense, but something has to really click.

Have you got a record coming out later this year? Give us some spoilers!

Definitely! I’m gonna drop a really good album. I can’t wait for that, I’m really happy with it because, honestly, all my sad stuff is cute, but I’m over it. I don’t really want to dwell on it. I’m really excited for my new stuff and looking forward to sharing it because it feels like a whole new phase for my sound. More mature. As I said earlier, I’ll never lose sight of who I am and what I represent, and everything I’ve built to get here. But I’m definitely treating this more as a job rather than just a fun hobby that’s getting me attention. I really want to keep pushing out things for people and keep creating, involving everyone in what it means to be in CLIP’s world.

Backing up a bit on the coolness stuff, I’ve read that you’ve been associated with the status of a new “it girl.” Sometimes defining someone, even with something very positive and cool, like ‘it girl,’ can feel cagey.

I don’t know. I love the term and everything about it. Growing up, I was so obsessed with what it meant to be an ‘it girl.’ But I realized that anyone can be that, It’s something you embody; it’s how you carry yourself as a person. I value my authenticity more than being boxed in as an ‘it girl’ because that label comes with so much behind it. It reminds me of people in school who tried to chase that status and play into someone they’re not. You know an ‘it girl’ when you see one, and that’s not something you should be labeled as. It’s about what you’re doing for the community, how your art is helping people. I think that’s what really matters: being a figure and a voice, using your platform to help people feel heard and feel good.

This really feels like a CLIP manifesto.

I’m so anti-labels.

Even regarding music genres?

Yeah, exactly. That’s why I don’t want to choose a genre for what I do. I hate being boxed in, it suffocates me. Like when I was living in Texas, I was suffocating. I hate that feeling, anything that makes me feel like that, I just tend to stay away from.

You lived in Texas, LA, and now New York, right?

Yeah.

How has each city influenced your experience? Is this journey and evolution through the places you’ve lived reflected in your sound? I feel like there’s maybe a New York phase in your music and another that feels more like Texas. Or maybe I’m just overcomplicating things and projecting.

No, honestly, that’s very real, even if perhaps it’s something that unintentionally reflects in my music and sound. You’re not the first person to tell me that. I’ve had personal friends say things like, ‘Oh, this vibe is really Texas,’ or ‘This reminds us of Texas underground music.’ I don’t do it intentionally. Despite how I feel about certain places or experiences, they define me, and my music is me. It just naturally reflects without me even thinking about it.

Team

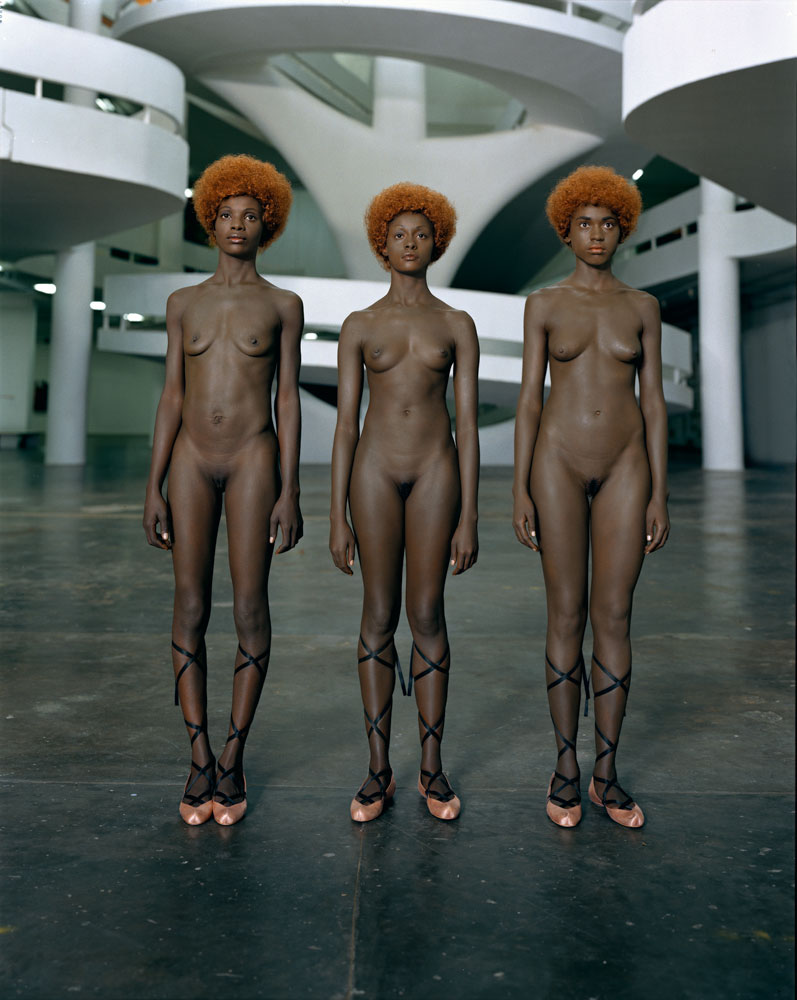

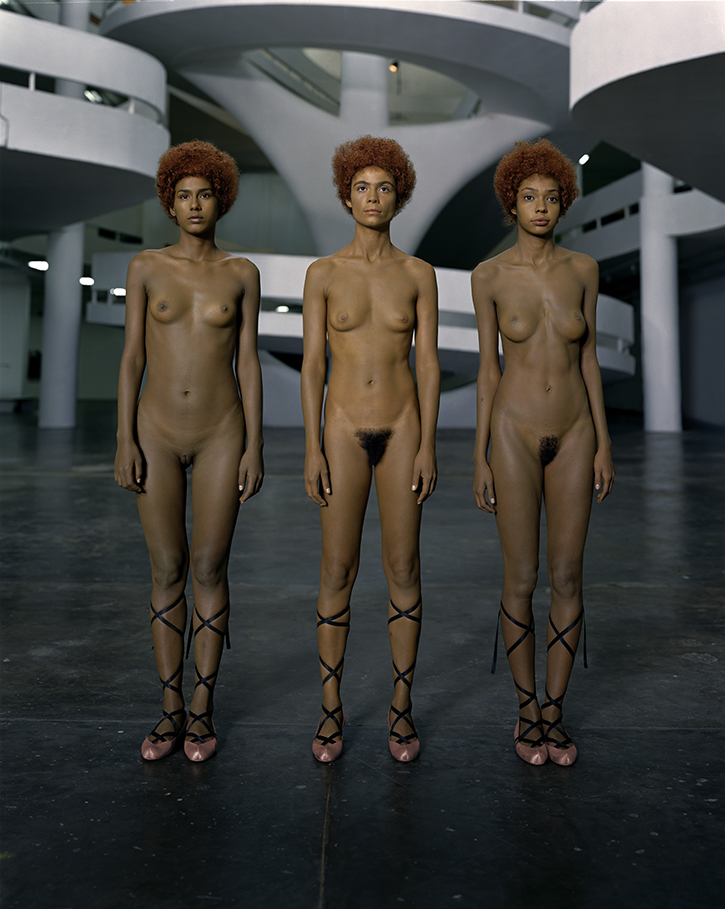

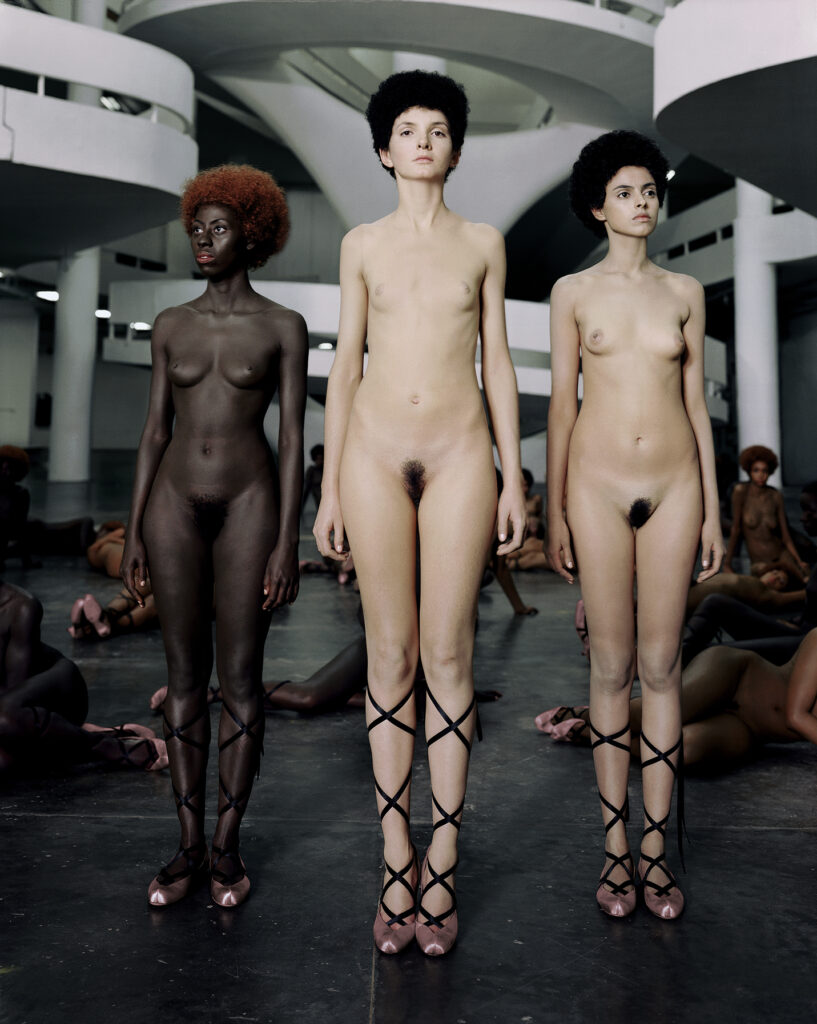

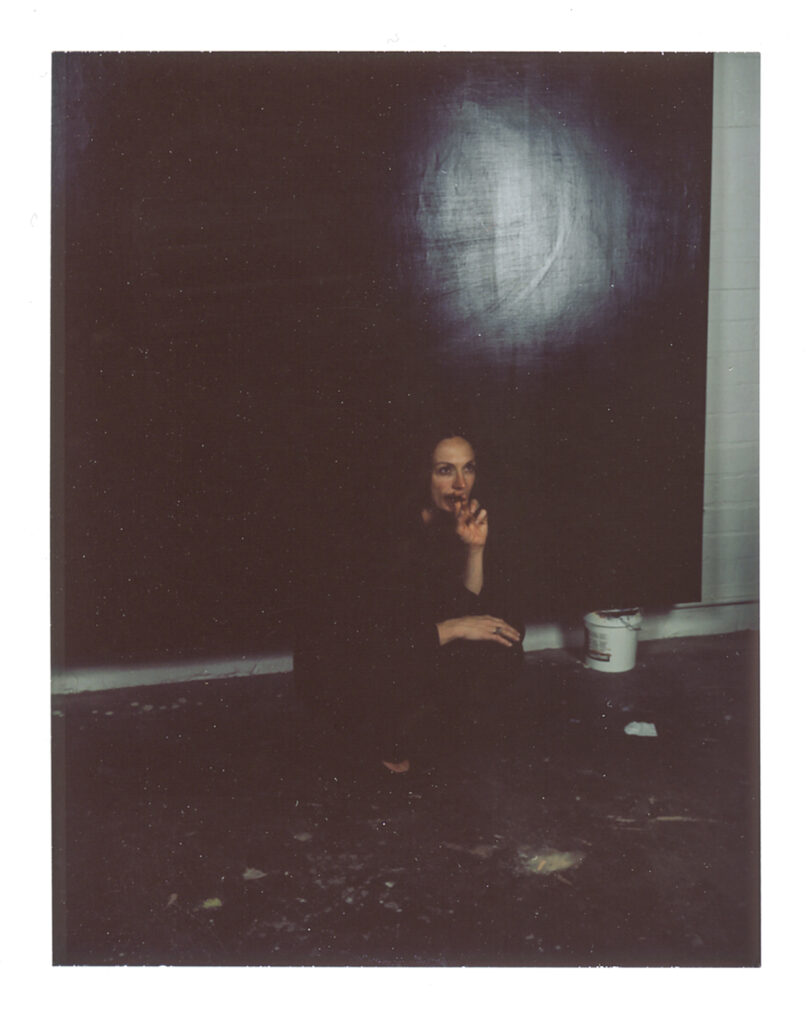

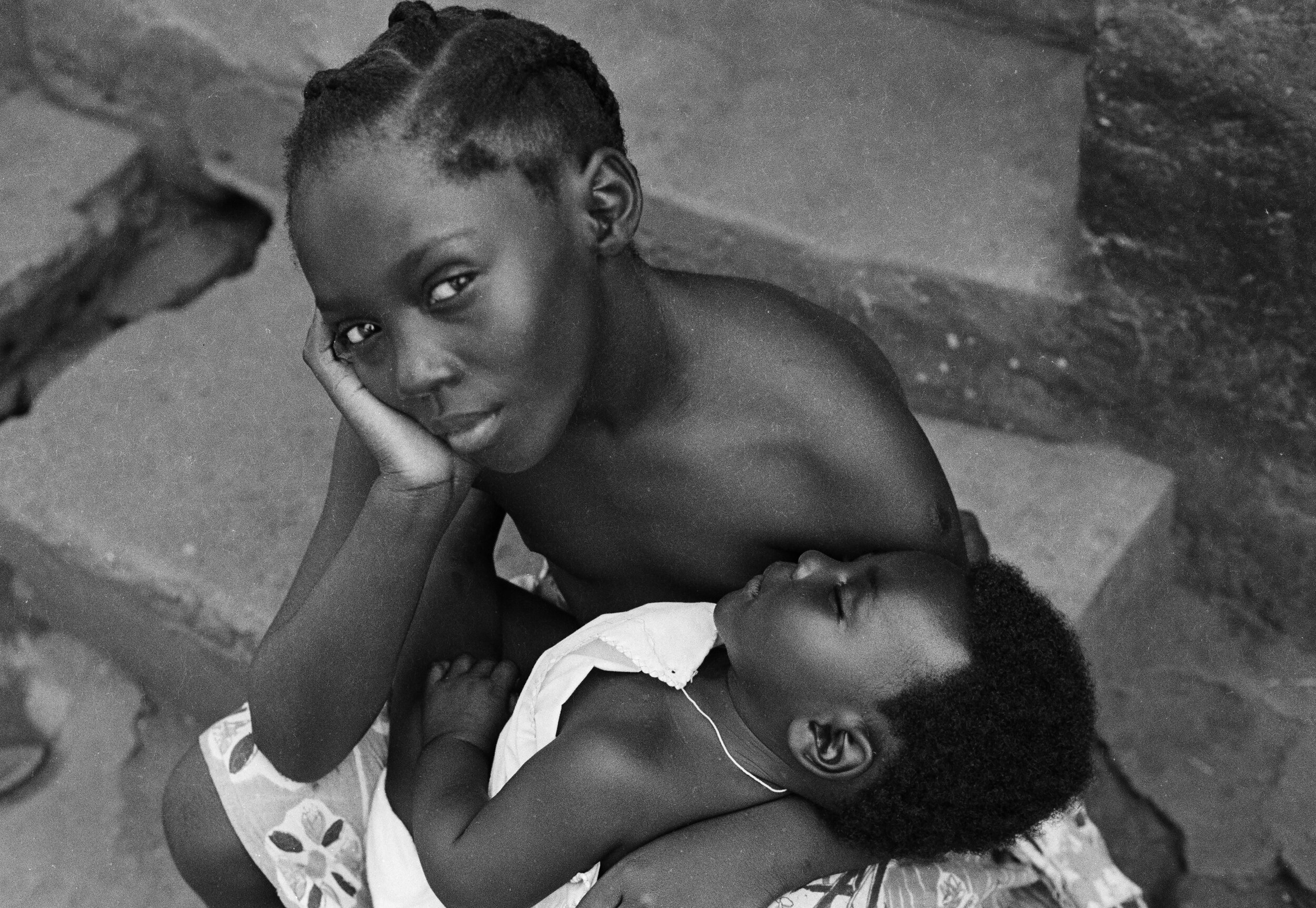

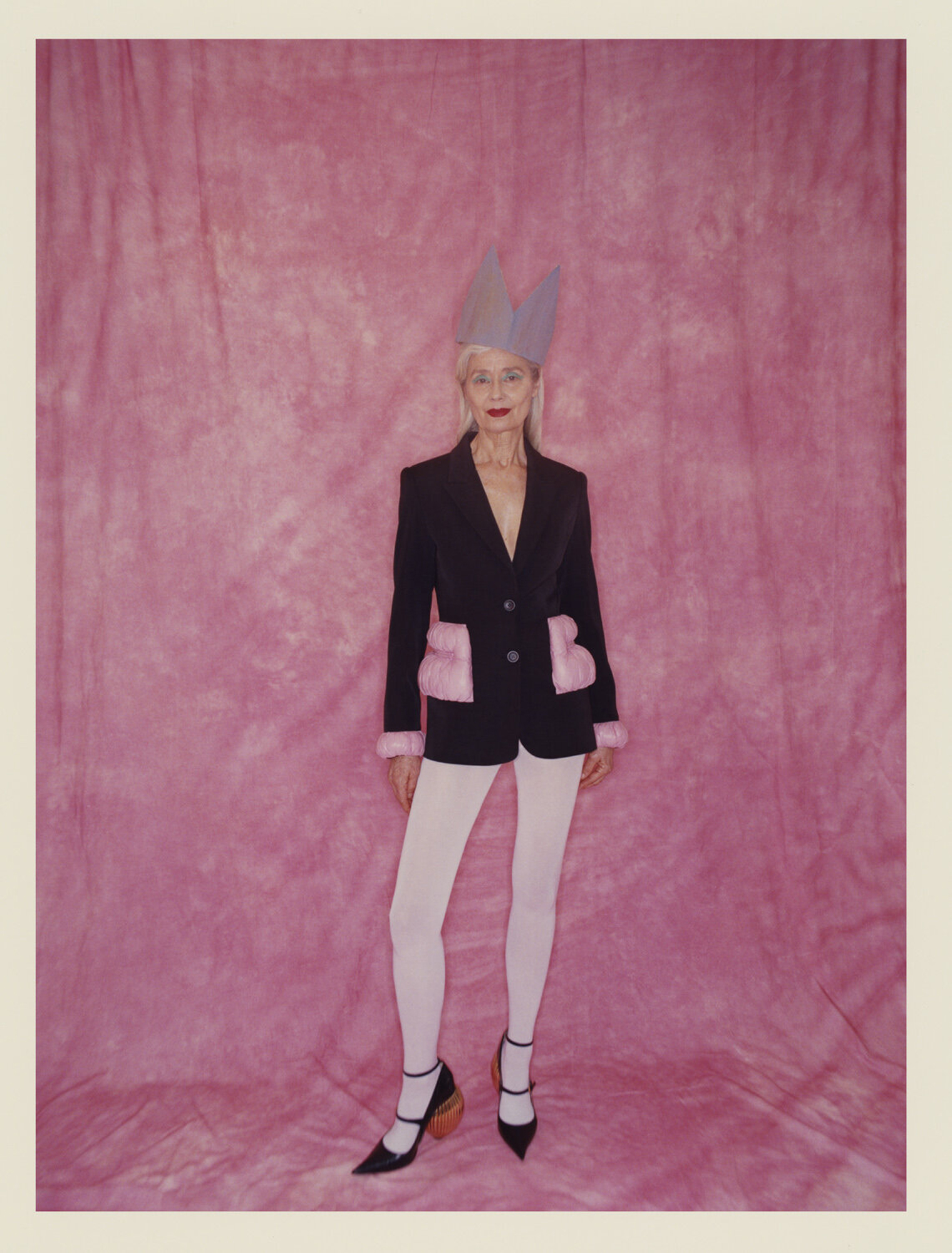

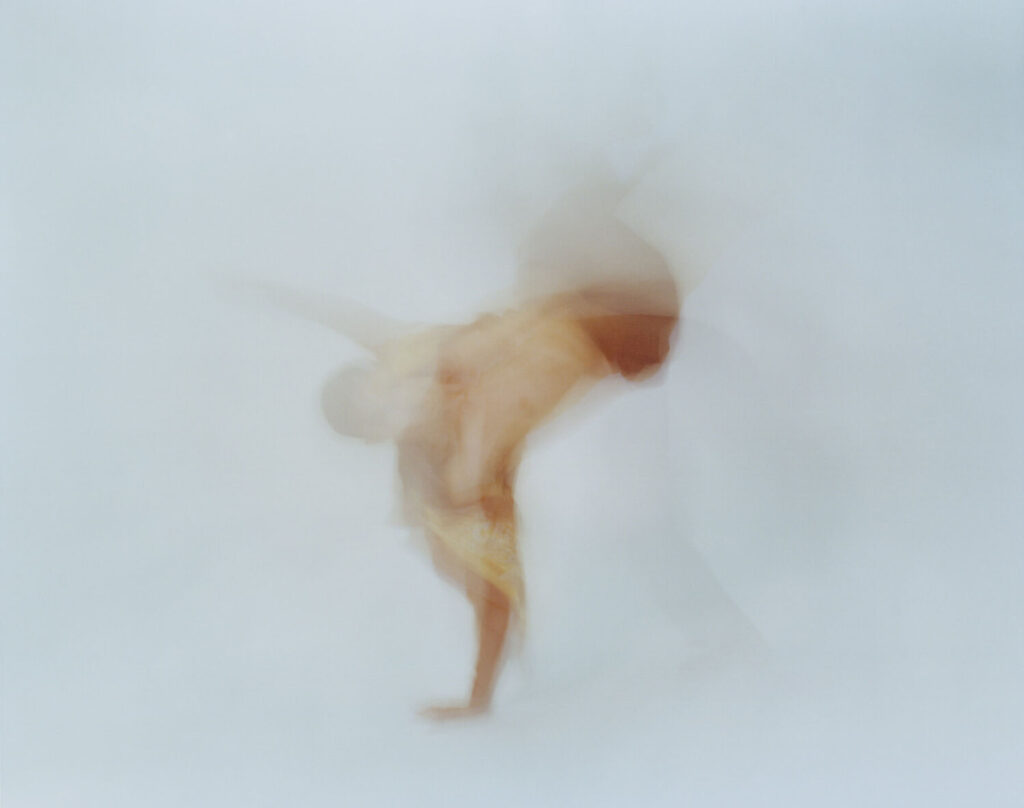

Photography · Lea Winkler

Styling · Zoey Radford Scott

Hair and Makeup · Jeanette Williams