Crafting Comfort: The Journey of HUSBAND WIFE

Founded in 2015 by Brittney Hart and Justin Capuco, Husband Wife is a New York City-based design studio known for its sophisticated yet playful and eclectic interiors. Throughout our conversation, we explored the profound connection between “comfort” and contemporary design, delving into a nuanced discussion that intertwined social and cultural analyses of the concept.

To start our conversation, I’m intrigued to learn about the journey that led to the establishment of Husband Wife.

Our name sort of started as a joke. We bought the domain name for our wedding in 2010 while we were still working for other designers. As life went on we realised we wanted to have a bit more control over our lives and express our own design visions. We realised we already had a website….and then a name. It felt a bit tongue-in-cheek but also mildly anonymous, which we like. More importantly, it led to us thinking about what it meant to do this together, and that design can be about duplicity and negotiation. Although we share so many common interests, like our guiding light of sci-fi and antiques, we’ve realised that it’s more our differences that are our strength. We have the respect and capacity to see each other eye-to-eye, but we want there to be differences in opinion. Now that our team has grown, we have built this into our mantra.

Describe Husband Wife in just three words.

Romantic, restrained, considerate.

Given your New York base, how do you perceive the city artistically, and what changes do you anticipate in its artistic landscape?

We both come from a very specific music scene that has a strong DIY ethos and for us that is a nostalgic detail we hold on to. Simultaneously, New York seems to balance on this tightrope of time where everyone pushes forward while still having nostalgic concepts of the past. We’ve accepted this and bred it into our thinking about projects. For many artists and creatives in NYC, some of these notions of time are coming to the forefront in different ways. For instance, we are already seeing our generation grow companies that reject prescribed notions of the future, most noticeably embracing craft (seeming of shoot of the DIY-ethos) and narrative (in varying ways, see Bode, TIWA Select, Studio Giancarlo Valle). For us, we see this manifesting in our own way; always searching for a thorough line of modernity where this layering of time creates a framework for real life. We hope that the people that occupy our spaces have a voice.

Could you elaborate on your definition of “comfort”?

In the same way that the city seeps into an artist’s perspective, every gesture within a home imprints on the person experiencing it. To us, when you’re truly aware of your space and everything in it, you’re engaging in the present moment in a way that keeps you emotionally awake. We see our spaces as a bespoke response to the outside world and take the time to study our clients’ lives. For us comfort is this attention to the users movements and feelings. These can be small moments that feel personal and considerate. Observing the weathering of a wooden cabinet or the patina of a brass bowl; the comfort that comes with this idea is almost meditative to us.

Building on the idea of comfort, what societal and cultural needs do you believe people are seeking to fulfil ?

Connection. We believe in the power of local communities, from our home in Bed-Stuy Brooklyn, to subcultures in music, to the NY design scene – we’ve seen how these relationships affect life positively. New York City, in particular, shows how these different groups can interact and, we believe, was a real reason for acceptance and cultural change in the 21st century. Sadly, many of these smaller scale communities are disappearing. We believe homegrown communities create a sense of comfort and belonging and we don’t want to see them disappear.

We try to express this in our work by embracing our communities and supporting others’. We design our spaces to foster connection – sometimes it’s the smallest acts like a refurbished piece of furniture or art from a local gallery that reinforce this notion. We believe most people seek a sense of place, grounded in comfort, and crafted through meaningful connections.

Your work often explores the interplay of volume, scale, and form. Can you delve into how you leverage these elements in your designs?

Everything we do is an expression of tension layered in research. A brutalist building may inform the design for a piece of furniture. A vintage picture frame might influence paneling applied to a dressing room. There are so many lessons we can glean from historical codes, interpreting them in subtle ways, and tailoring to our clients’ lives. Ultimately we try to use unexpected interplay in volume and form as a tool that transports our clients (and perhaps resets) their perspective

Something we refer to often is Marina Abramović and ULAY’s ‘Rest Energy’ art performance piece where each person is responsible for holding the other in steady balance with what’s happening in every moment. Abstractly, this is how we go about every project – holding mirrors up to each other’s instincts. Practically, we believe moments of tension in design (the unexpected) create follies that allow engagement in the moment.

Can you share some of the most emotionally resonant projects you’ve undertaken and what made them particularly memorable?

Every project is emotional in its own right because each contains a completely idiosyncratic charisma that’s tied to the character of its residents, the minutiae of the building’s architecture, and the research that went into every object sourced for the space. This astute awareness of the relationships that are fostered with every brief – through our clients, collaborators, vendors, and team – is something we hold dearly. It’s a dance of challenge and joy, of puzzle-piecing and of letting go. It’s an immense privilege to be a part of people’s interior lives.

That being said, one project that has been long important to us is a residence we are developing in Ohio for a lovely couple and their growing family. This is a large historic home on the National Historic Register with an incredible, beautiful, and weird composition. This is a gothic mansion with true historical craft and a wild history of ownership. Details include a repurposed chapel with original confessionals, limestone wrapped gardens, and a vaulted dining room on the top floor of the property. We have been working on the project for five years, slowly creating a space that reconciles our clients’ grand property with their humble and family-oriented lives. This was a client that took a risk on us quite early in our studio’s existence – so in a sense, we feel that we have all grown together.

Looking forward, what aspects of Husband Wife’s future are you most enthusiastic about, and can you give us a glimpse of any upcoming projects or collaborations?

Having completed our first hospitality project earlier this year, we’re curious to explore more eclectic mediums of space moving into the future. The infusion of residential beauty into commercial settings can be an intriguing test of design’s malleability in which the intimacy of private space is translated for public consumption. At this moment in time, we are working on an eclectic residence for a well-known contemporary artist, composer partner, and two children. They bring their own sensibilities to the conversation. Finding our common ground – or more specifically – negotiating a design language has been a rewarding challenge. Here we are blending historical codes with modernity to create a vibrant, engaging space for her family to play, love, host parties, relax, and in New York – find as many places to hide storage as possible. In her words the result is “blade runner meets art nouveau”.

In order of appearance

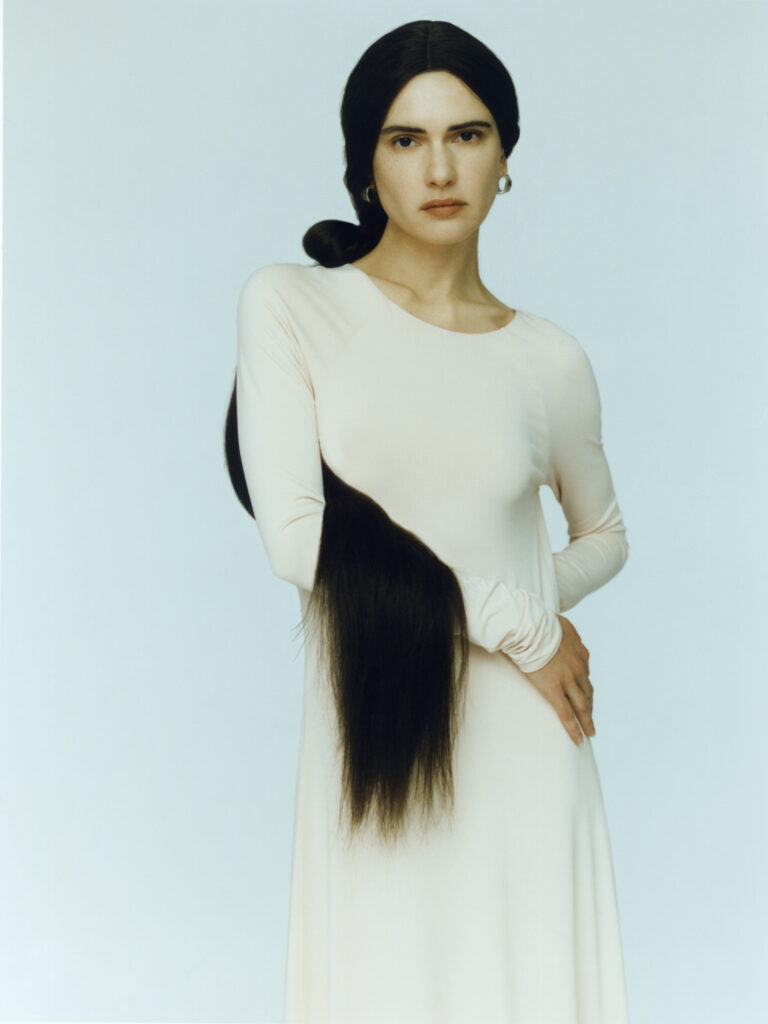

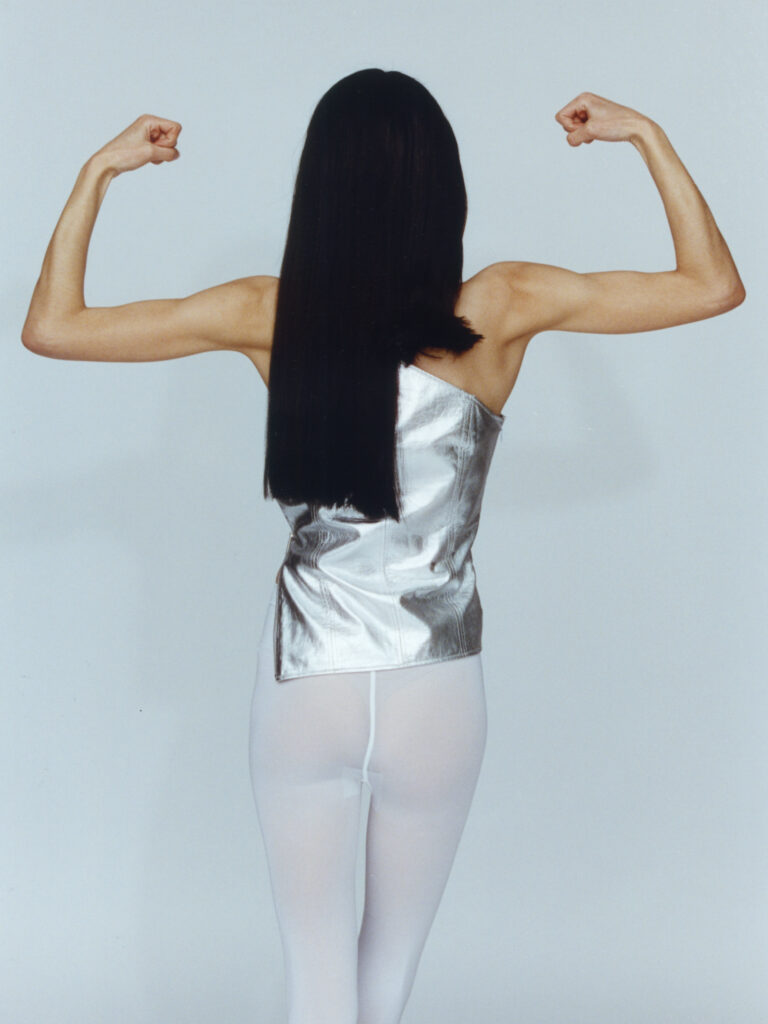

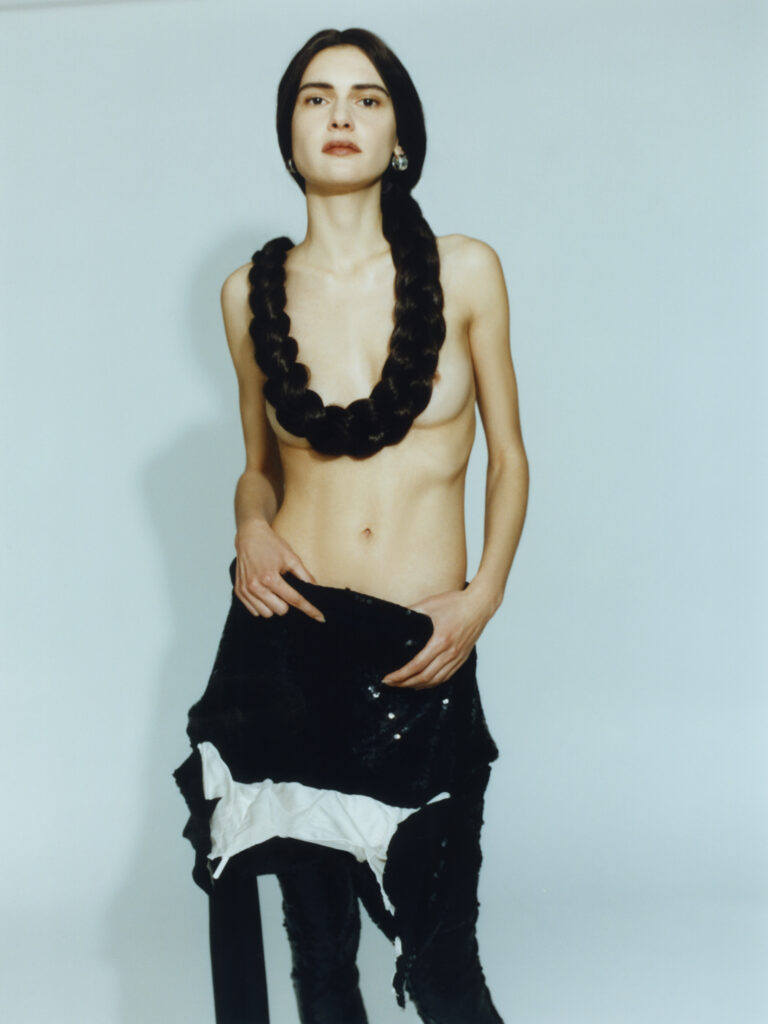

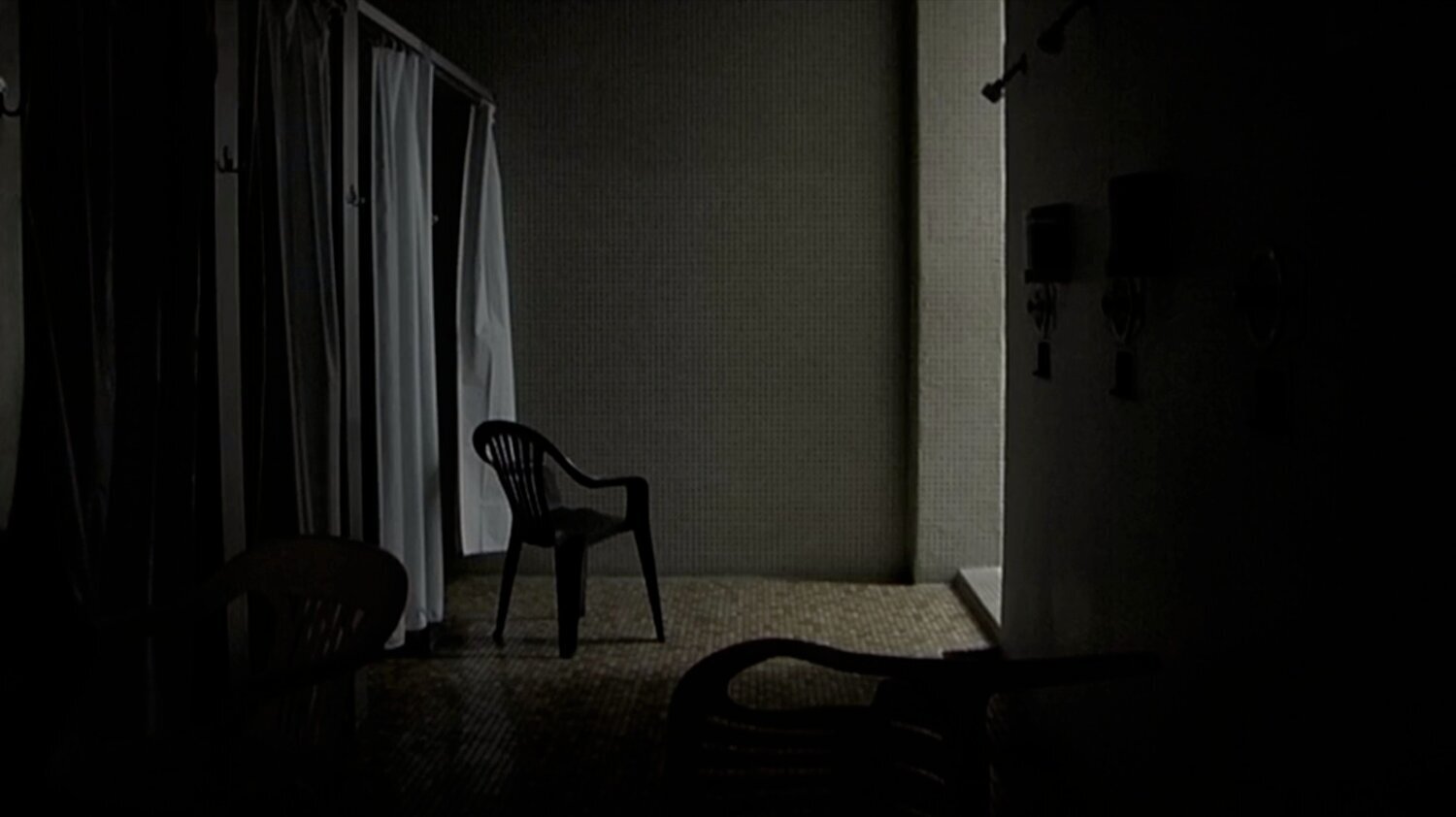

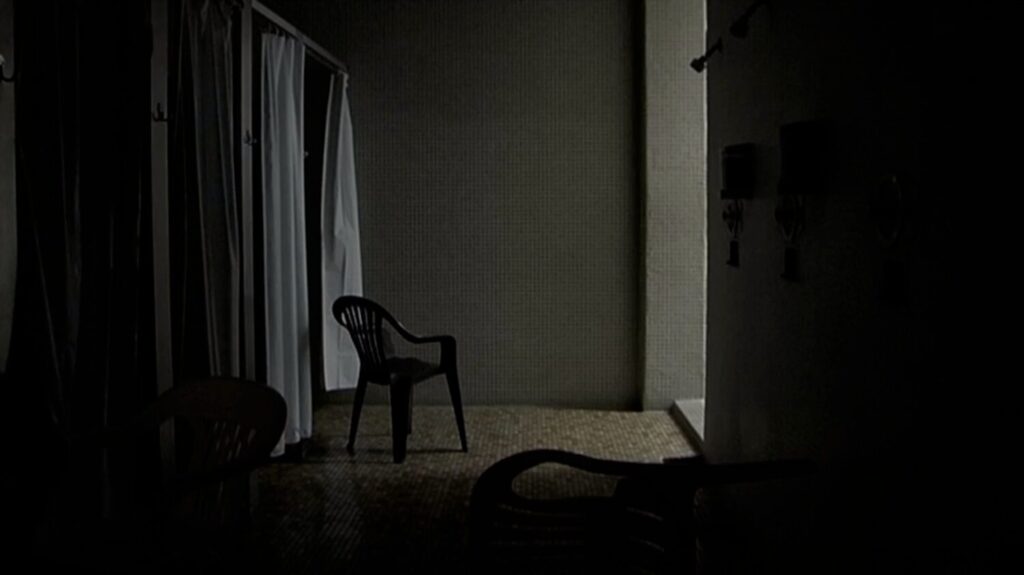

- Steinway Tower, Residence, New York, 2022. Photography by Nicole Franzen. Courtesy of Husband Wife.

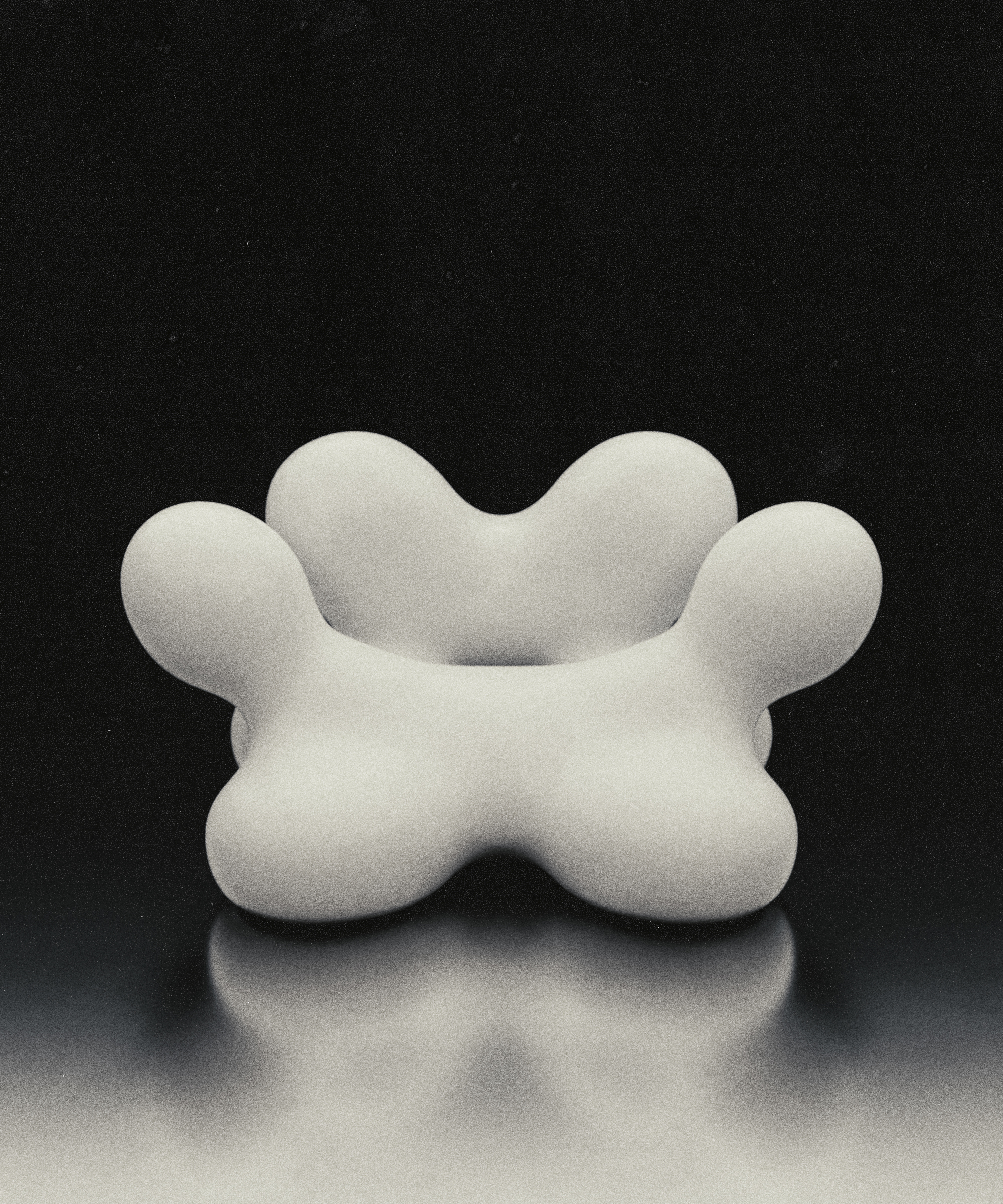

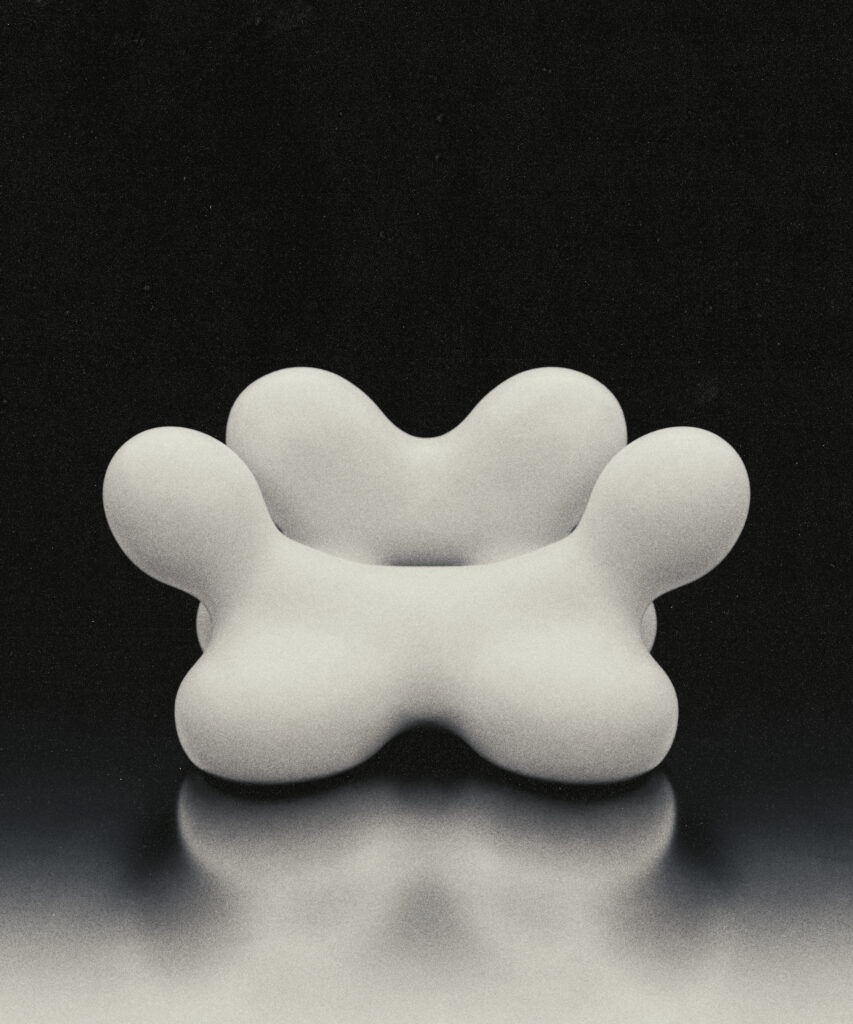

- One Hanover Square Offices, New York, 2023. Photography by William Jess Laird. Courtesy of Husband Wife.

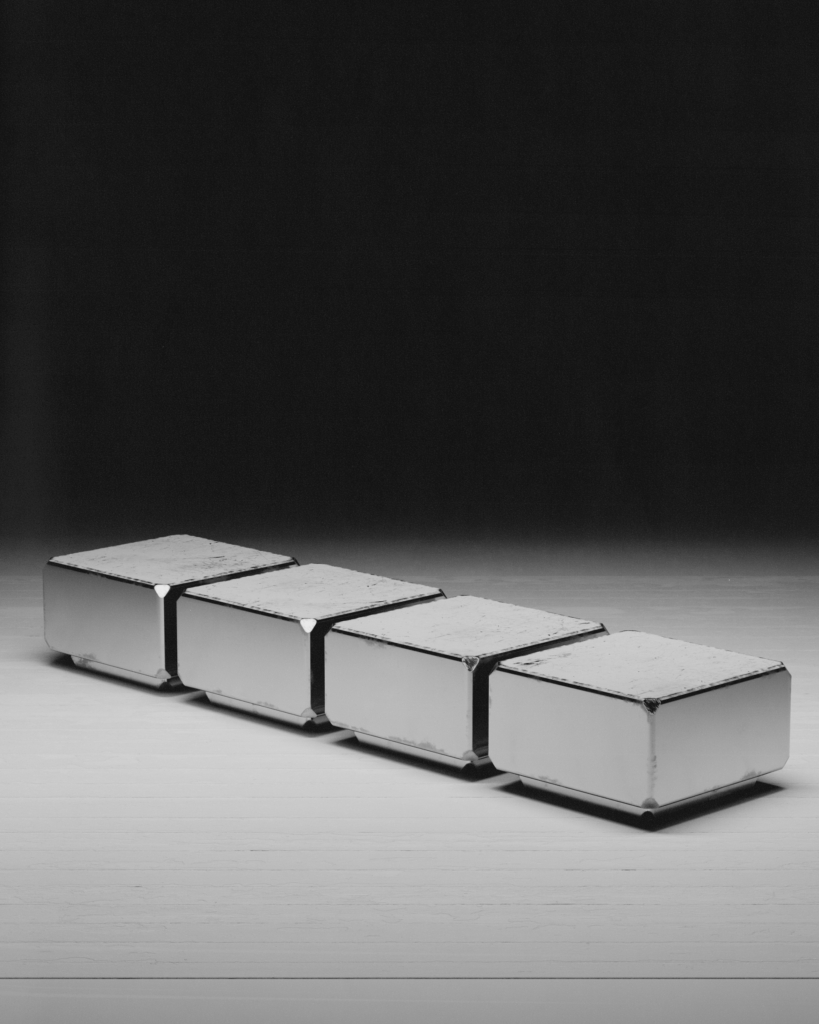

- Orange Barrel Media Office, New York, 2023. Commercial Project. Photography by Nicole Franzen. Courtesy of Husband Wife.