Relieving trauma has Filippo Scotti revisit parts and memories of himself

Filippo Scotti wears a worried look as he fires off apologies for being five minutes late into the call. He was helping his friend with a project and lost track of time. He asked him to pedal fast when the two breezed through the street on his friend’s bike, hoping to catch the interview on time. After a bout of reassurance that he has nothing to worry about, he drinks from his 1.5 liters of water bottle to fight off the 38 degrees celsius heat crashing over Rome. Drinking tons of water forms part of his daily routine along with hours of physical training for his next project. NR tries to break through the secret project, but Filippo’s lips remain sealed. The only piece of information he gives is that “imagine wearing a t-shirt when it is 10 degrees out there. I have to prepare my body for that.” He assures us that he will not be doing jump stunts like Tom Cruise. Even if that were the project, Scotti would buckle down in a heartbeat to physically prepare for it.

On starting out

Scotti started out as a theater actor in Naples at the age of 16, and even before that, his mother had encouraged him to try his hand out at acting when he was 11. While on tour with his theater group for shows, an agency signed him, the gradual shift of the young actor from theater to cinema. His new lineup brimmed with auditions where he would prepare each day to spew out his memorized lines with depth to match his character’s emotions, almost melding with his own. Those moments culminated in Scotti earning the role of Fabietto Schisa in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Hand of God (2021). Now that he is thinking about it with NR, he admits he got lucky.

Working for the movie nudged Scotti to look at the cinema industry as a spider web where he always has to move, audition, secure roles, act, and go on press tours. The cycle repeats, and he admits it took him a while to get a hang of the rhythm. But his strike of luck keeps him in the spotlight, project after project. “I am also lucky that people whom I worked and work with trust and have taught me how to be and stay in character, to always be ready for what is coming. I am always learning and never stopping, and that is a double-edged sword for me. It scares me, but at the same time, it excites me. The whole experience is just wonderful,” he says.

On preparing for the shoot

From luck, the conversation flows to how mathematical he sees the process of being on set is. Everything seems to be planned – a miscalculation in schedule, equipment, script, and post-production means shooting delays. The viewers see the finished product flashed on the cinema screens, but it only scratches the surface of what happens behind the scenes (not the bloopers that seem to detract the attention from the hard work invested in producing and making a movie).

Scotti tells NR that often he wakes up early only to start shooting late in the afternoon or at night. The physical and mental preparation he undergoes also comes in handy when his first hours are spent idly waiting for his turn. Then, when he acts in a scene and the first take is not good enough, it might take two, three, four, five, or more takes before he can settle down. “During the shoot, I block out any thoughts so I can stay focused on my character. When I do more than five takes – even four because I always target a maximum of three takes – I start to hit this wall and fall into this repetition. It affects the way I act, so I strive to get it all done before the third take,” he says.

On relieving trauma

For The Hand of God, some takes took more than three times, and as the shooting went on, Scotti found himself in the shoes of Fabietto’s character, beyond the biopic he was portraying. He would think of ways to tap into Fabietto’s pain and tragic experiences, but would end up feeling obligated to play the role. Sorrentino noticed, sat with him, and told him that he should give his truth to the lines of his character. “If I am to say my lines, I should think of my truth – the painful events that happened in my life,” he says. Scotti followed the director’s advice and soon, he relieved his truth, even if it meant digging up the past he had already buried. “While I did not live the tragedy Fabietto lived, I felt the pain he felt as I remembered my past,” Scotti tells NR.

When asked about the experiences he went through, Scotti pauses. Seconds of silence have passed before he speaks. “I am only going to share one event that was strange for me,” he begins. When he was in high school, Scotti enjoyed the company of his friends, the topics his teachers delved into, and the theater classes he had in between. Yet the young actor felt as if he was in limbo, the weight of an unknown sensation seemed to be putting him in stagnation. He felt stuck and he could not pinpoint why. “Until now, I find it hard to describe the feeling,” he says. “I wanted to study, but I did not want to study. There was this push-and-pull feeling that tired me out.” Suddenly, Scotti was playing a role of a character who was stuck and wanted to find a way out, a real-life portrayal of a role he saw in movies. Like a coming-of-age movie, he figured out that he felt free after he pursued acting full-time. He still studies for pleasure from time to time, but he no longer has time to beat. His pace, his time.

Relieving his past traumas for his role in The Hand of God made Scotti realize how, at times, he has to take off his mask and acknowledge and understand his vulnerability. “To accept it is difficult sometimes,” he says. “But I feel lighter afterward, knowing that I have understood what it meant.”

On fame and recognition

Scotti has experienced being recognized on the street for his role as Fabietto. When asked if the gradual build-up of fame surrounding his career affects him, he says that he is more focused on the emotions and depth he dedicates to his roles rather than the recognition he receives from the public. It pleases him to know that he can influence viewers with his acting – he even receives direct messages on his social media, which he reads, double taps, and treasures – and Scotti reminds us that the Scotti who portrayed a role in his previous project differs from the Scotti today. “Am I the same person? Would I be able to do better in the next project? Responsibilities come and go. I love being the message people can relate to, and I hope to continue that.”

On moving beyond acting

During his press tours for The Hand of God, Scotti was asked at times if he wanted to be a director one day. He could not remember when he had said that, or if he had even said it at all, but somehow, it piqued the press’ curiosity over his next venture. For NR, he says he loves writing and the idea of crafting characters over directing a movie, but that above all, he would love to produce movies. “If I were to have the opportunity in the future, I would love to open my own production company,” he says. “It would be difficult but worth it at the same time. The idea is exciting, to be honest.”

Scotti already has a name for his production company, but he says he will keep it to himself for now. As for the movies he will produce, he wants some gut-wrenching scripts based on reality. They do not have to be drama or tragedy. He envisions his movies as means to address topics that the general public might not be open or ready yet to talk about or reflect on. While he is unsure of specific themes, his statement circles back to how he dealt with his trauma, a potential overview of the visual narratives he wants the public to see.

On reflecting on his own

As a fan of words, Scotti used to bring a notepad in his pocket to jot down his thoughts. They were gone the moment they crossed his mind, and he wanted to keep track of these phrases, hoping they would make sense when he revisits them in the future. Touring and traveling means he stays far from home and finds himself on his own. In the times he is in his own space, Scotti ponders on life, love, movies, his career, his next path, his decisions, his regrets, and what he might have forgotten to say or do. “For example, I am living in Rome and my family is living in Naples. It feels far and close at the same time. I check in with myself on what I feel when I experience this. Then, I write down my thoughts,” he says. He has replaced his notepad with a ‘notes’ app on his phone. He reminds us that his thoughts are not poetry, but just jumbled words that made sense to him at the moment of writing, a set of word vomit he feels acquainted with.

Filippo Scotti appears hesitant to share one of his personal thoughts. He fumbles on his phone and stammers as he finds an excuse to refuse. We assure him it is fine if he does not want to share anything. He calls his typed-down thoughts shitty and bad. We disagree. He turns his phone to the camera and shows a long list of saved thoughts on his app. He clicks on one and purses his lips. “Last night, I dreamed of your pain. Up close, I can see the waves of the sea,” he reads. Earlier, he said he wants to base his acting on emotions for people to relate with, a mission he eyes to fulfill by playing a character. His delivery for NR can attest that while he still has mountains to climb, he is already on his way to reaching their peaks.

Team

Talent · Filippo Scotti

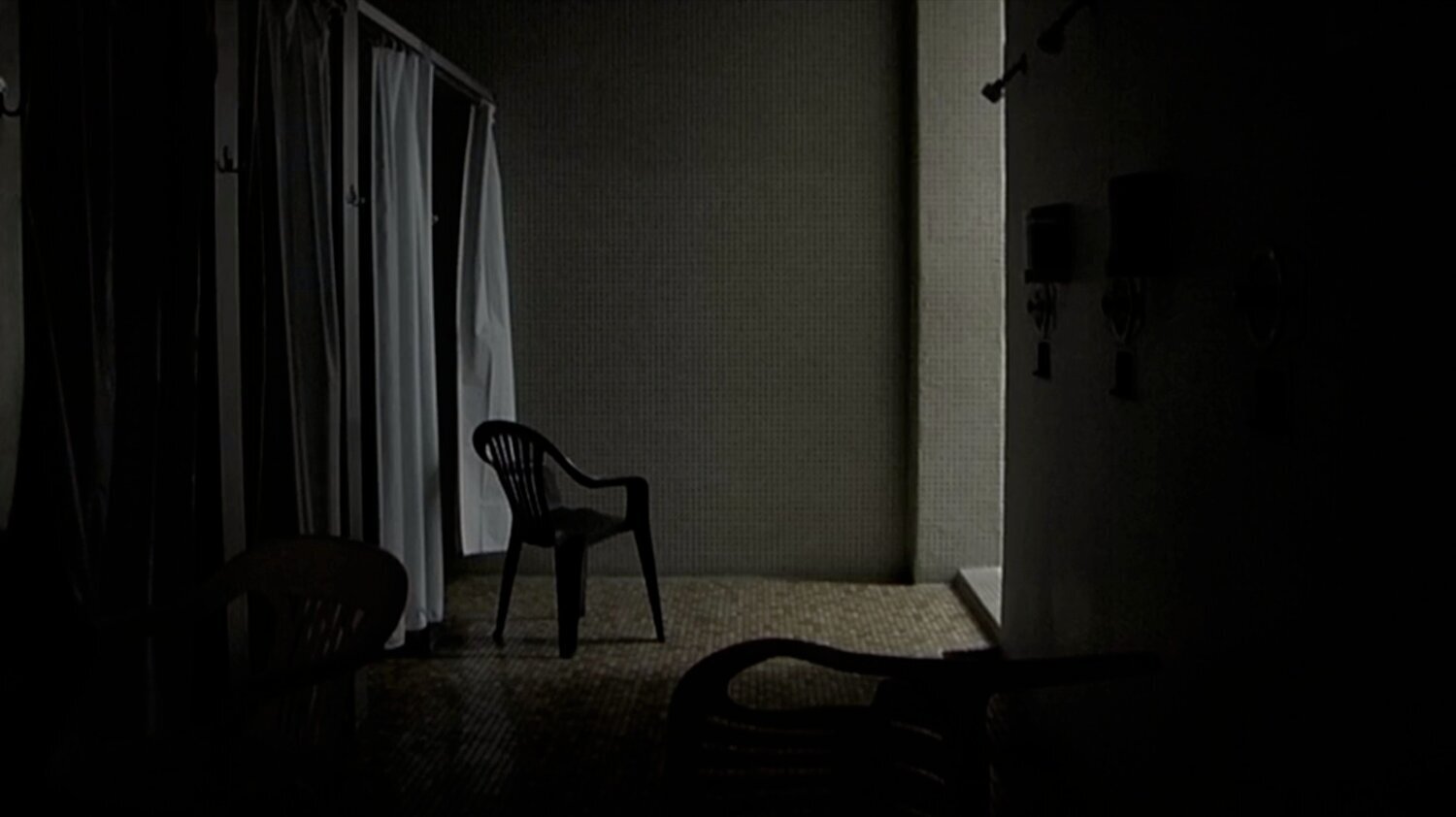

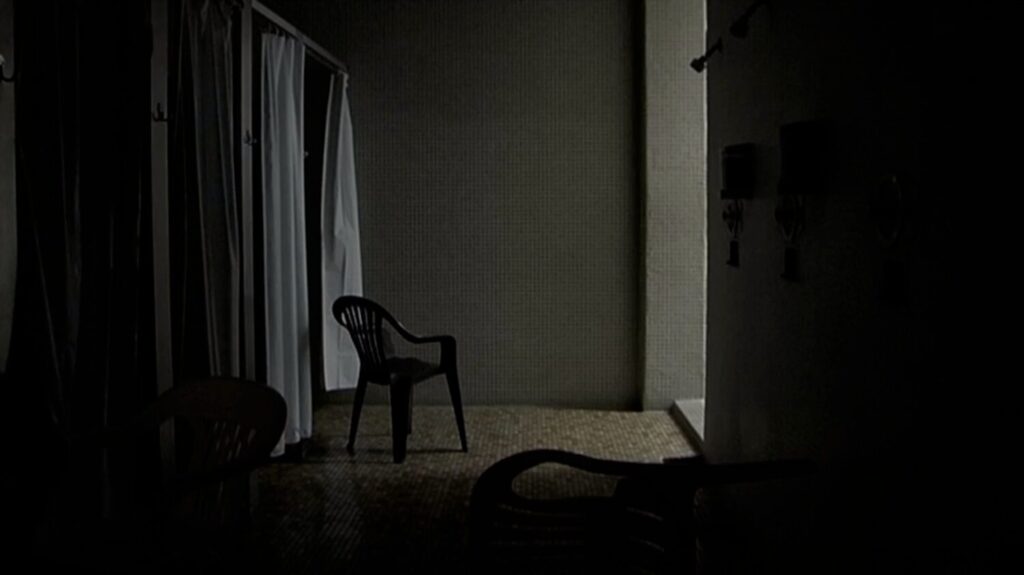

Photography · Bobby Buddy at Kaptive

Fashion · Victoire Seveno at Kaptive

Hair and Grooming · Miwa Moroki

Set Design · Clara de Gobert and Nico Plinio Lanteri

Agents · Carole Congos and Amal Jefjef

Fashion Assistant · Flore de Sermet

Special thanks to Gianni Galli

Designers

- Full look PRADA

- Full look PRADA

- Full look PRADA

- Full look PRADA

- T-shirt RON DORFF, jacket, trouser and shoes BOTTEGA VENETA

- Full look PRADA

- Jacket ACNE STUDIOS and t-shirt RON DORFF