“when you aren’t trying to accomplish something that serves your goals and you start to consider some else’s point of view, that becomes creative and that becomes fun”

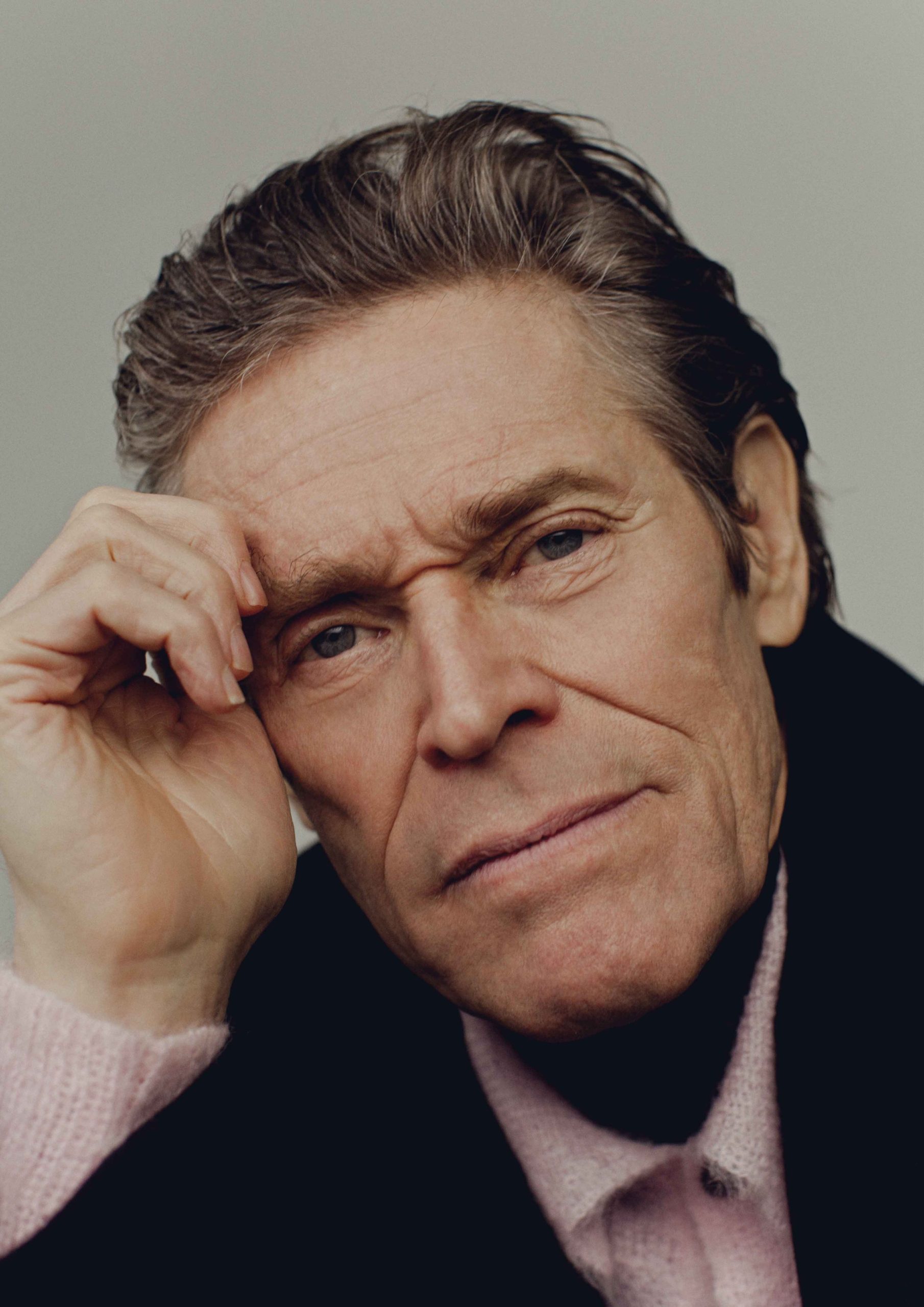

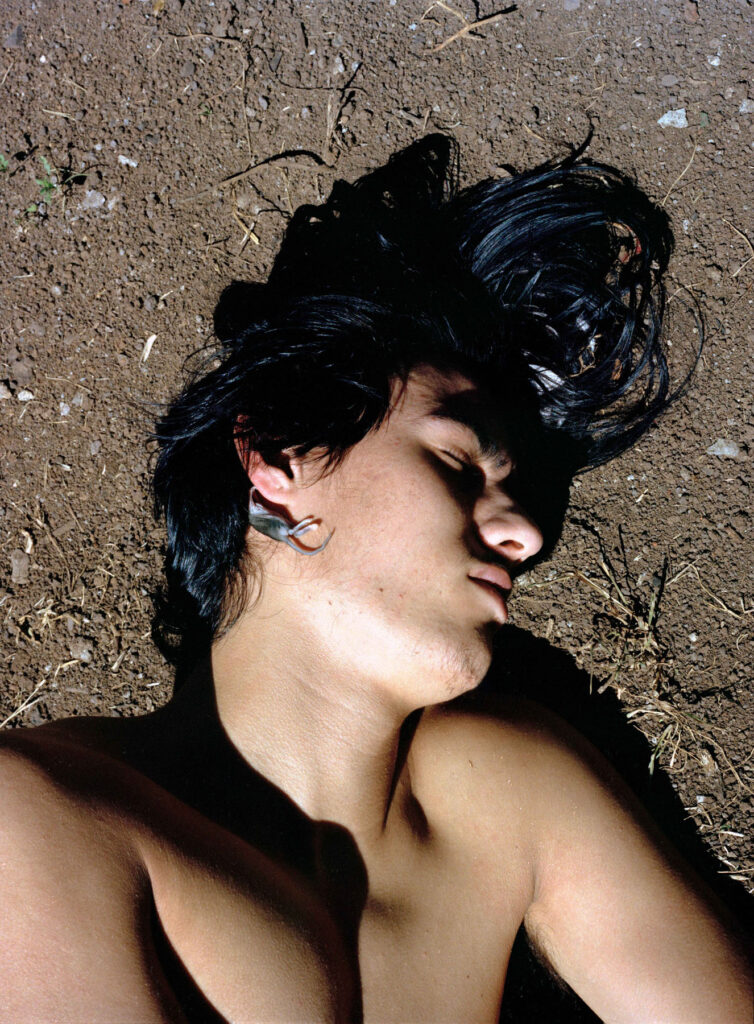

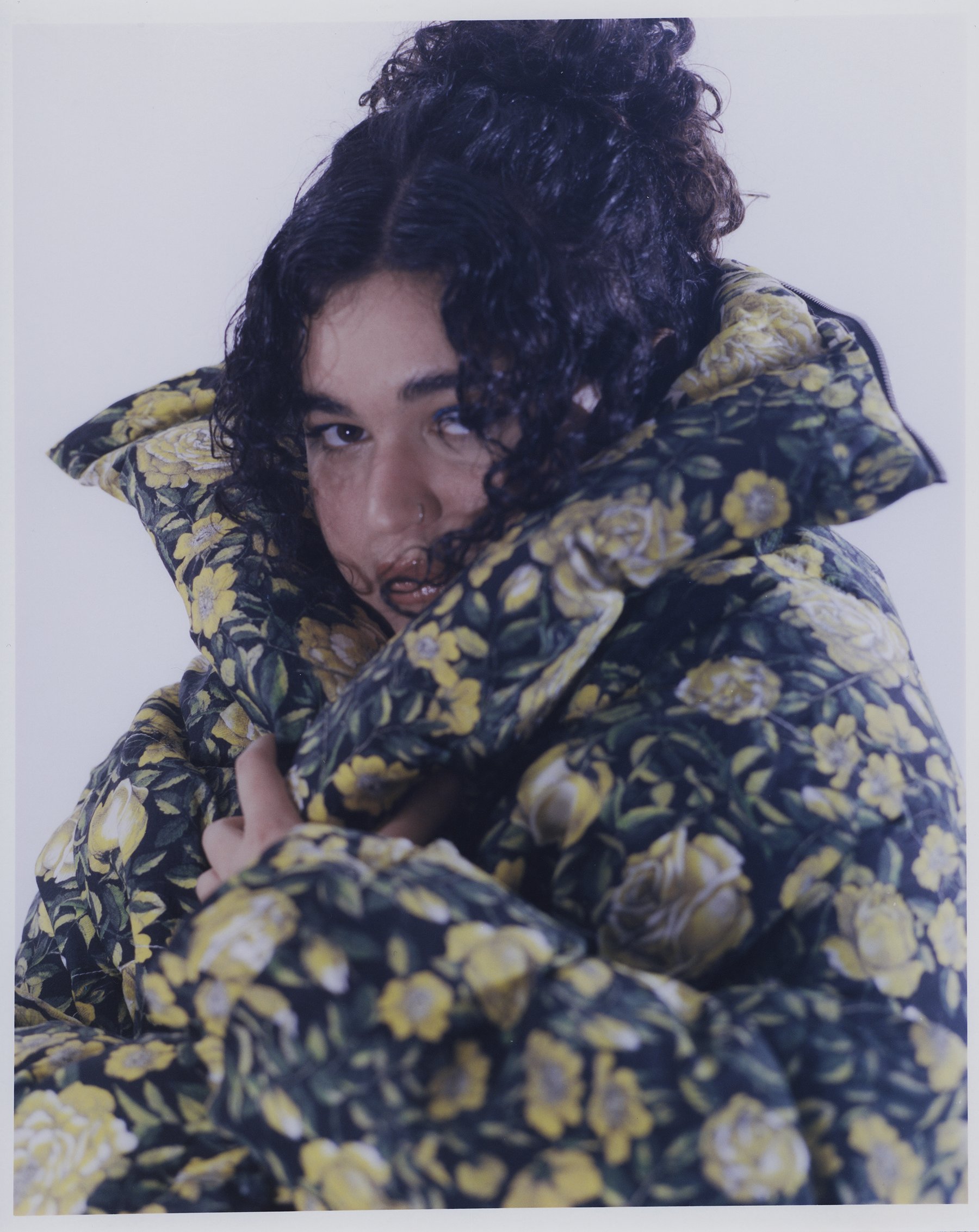

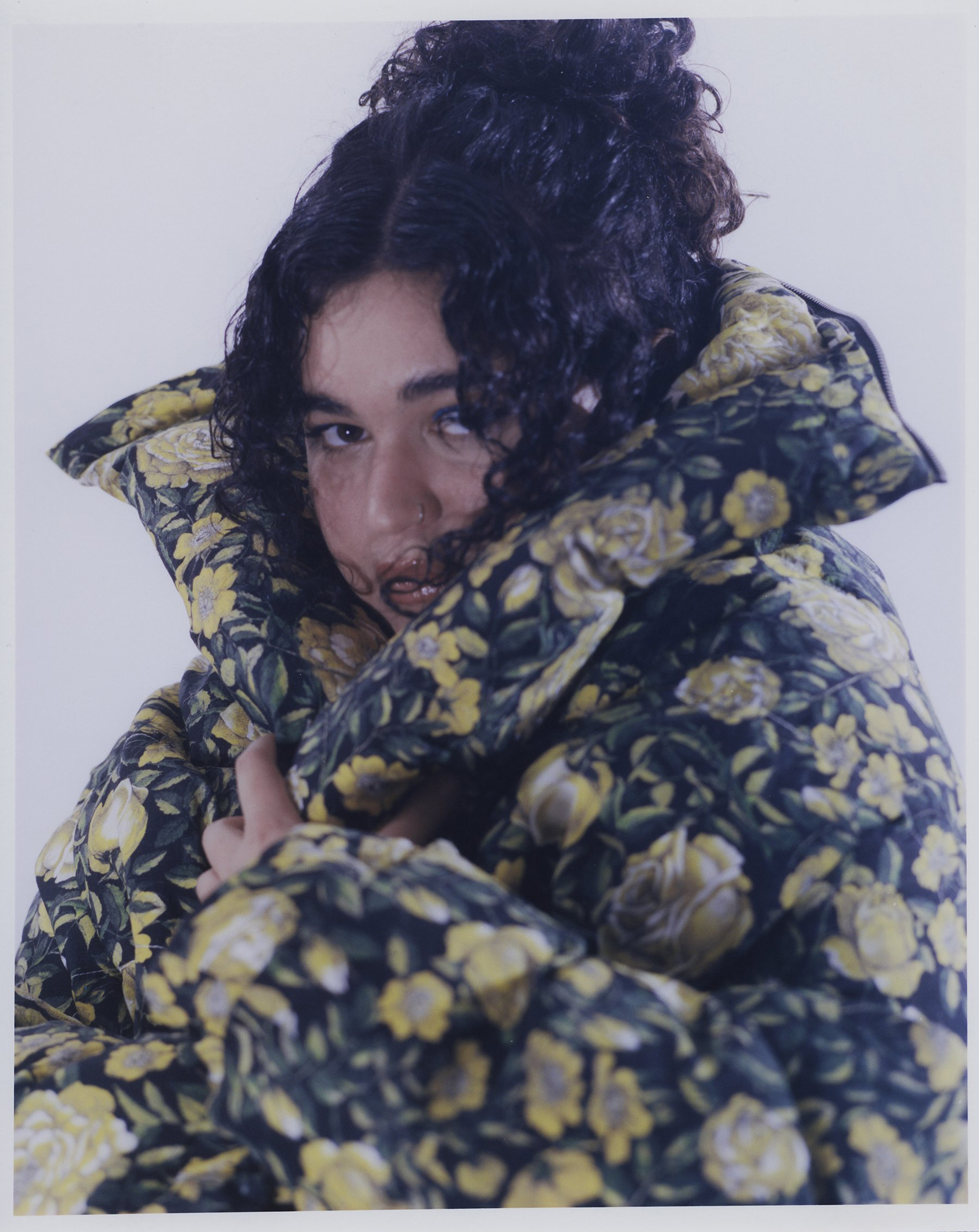

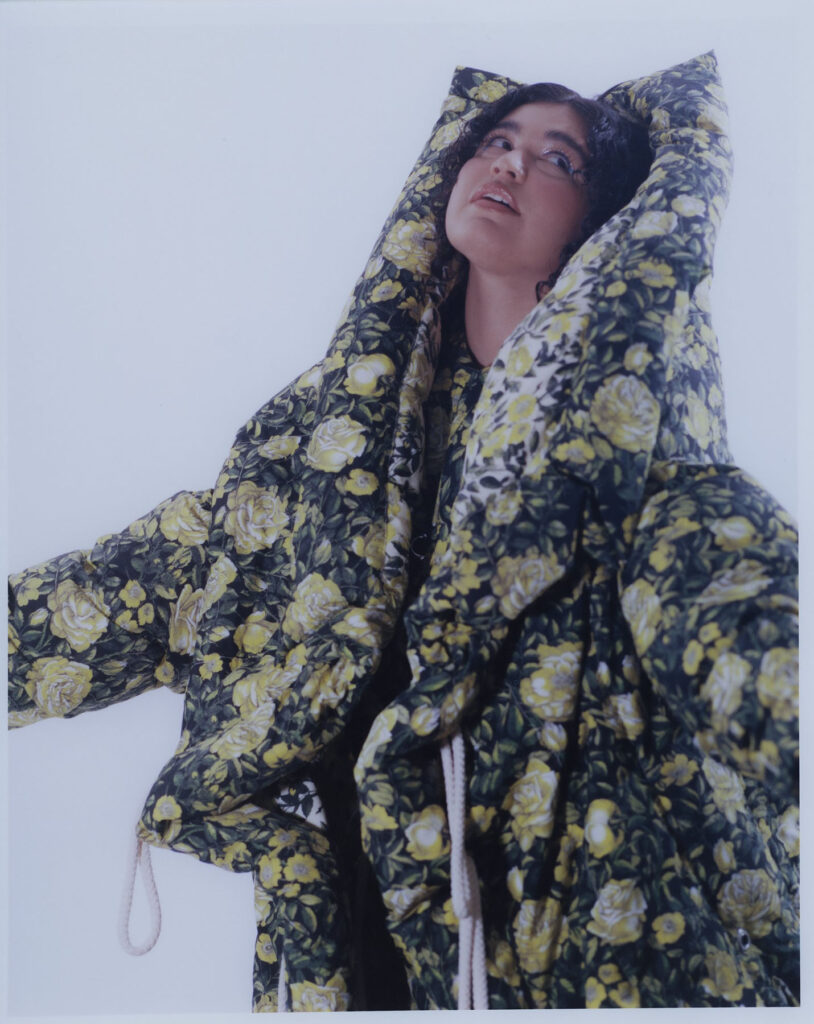

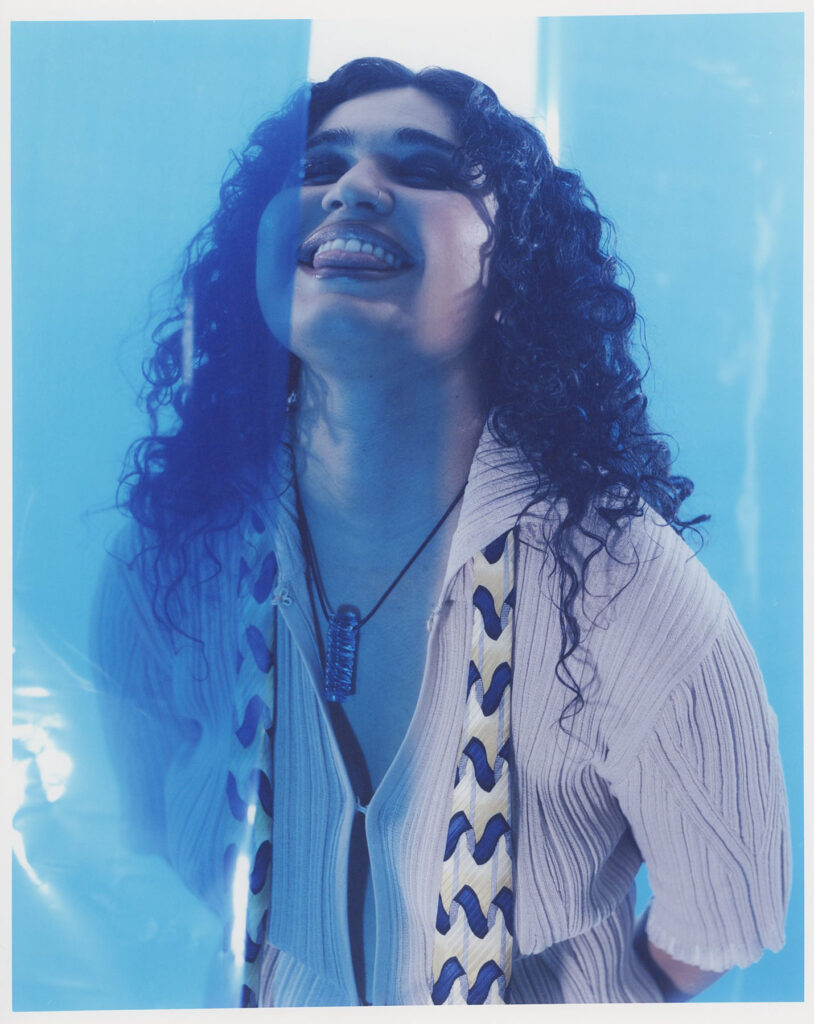

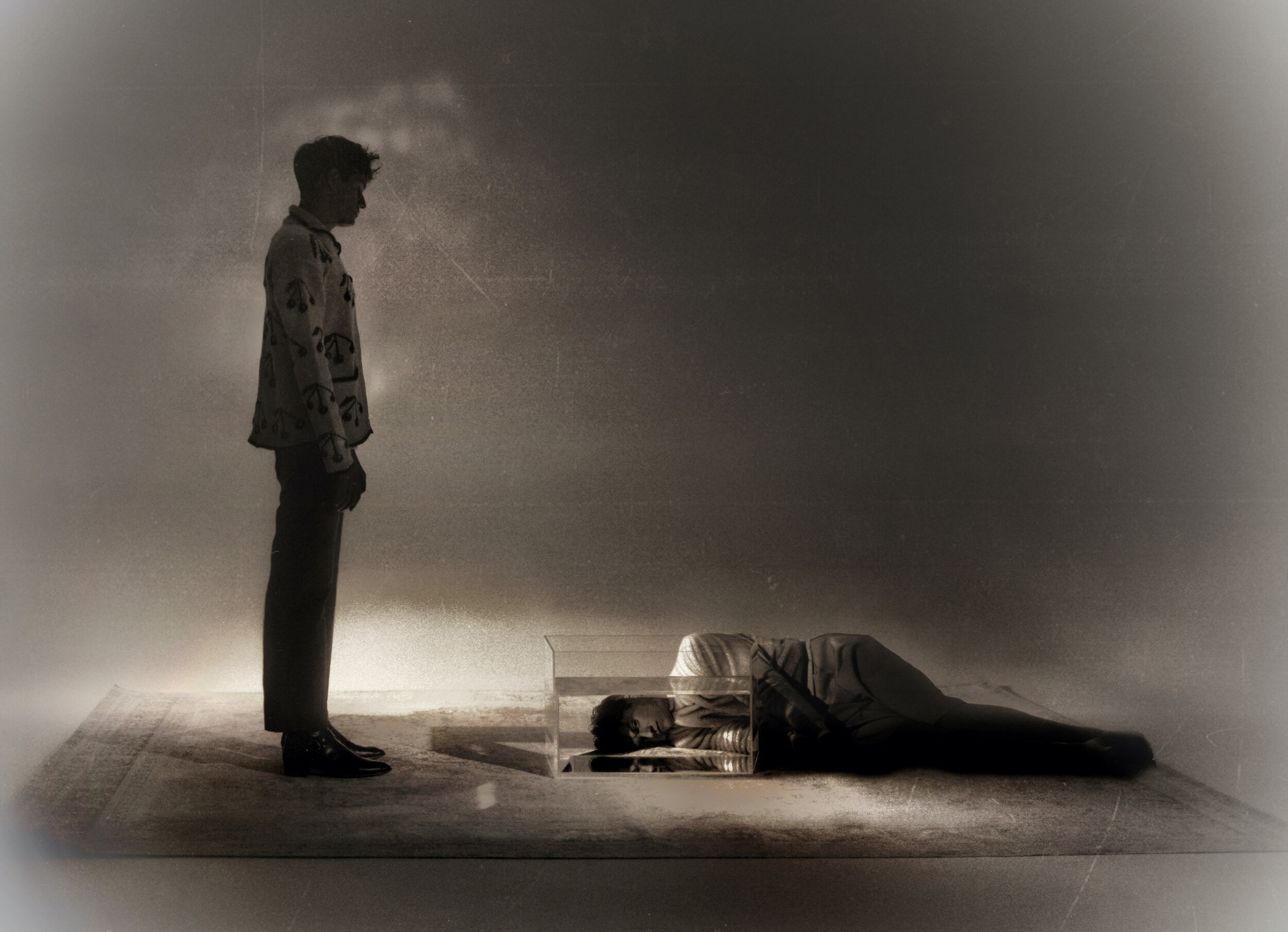

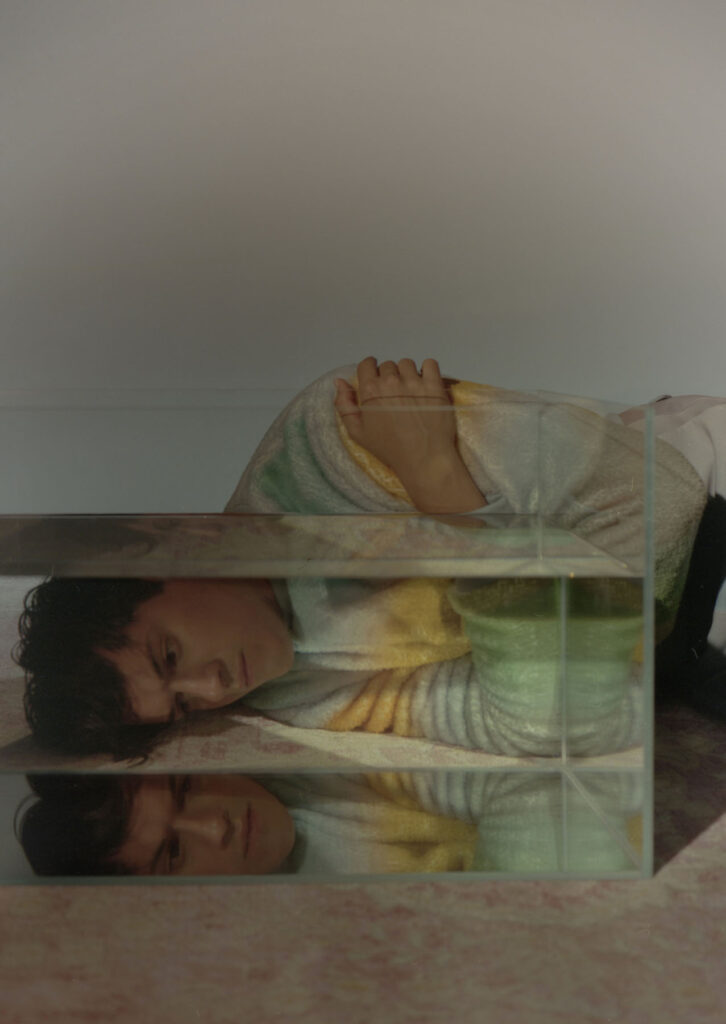

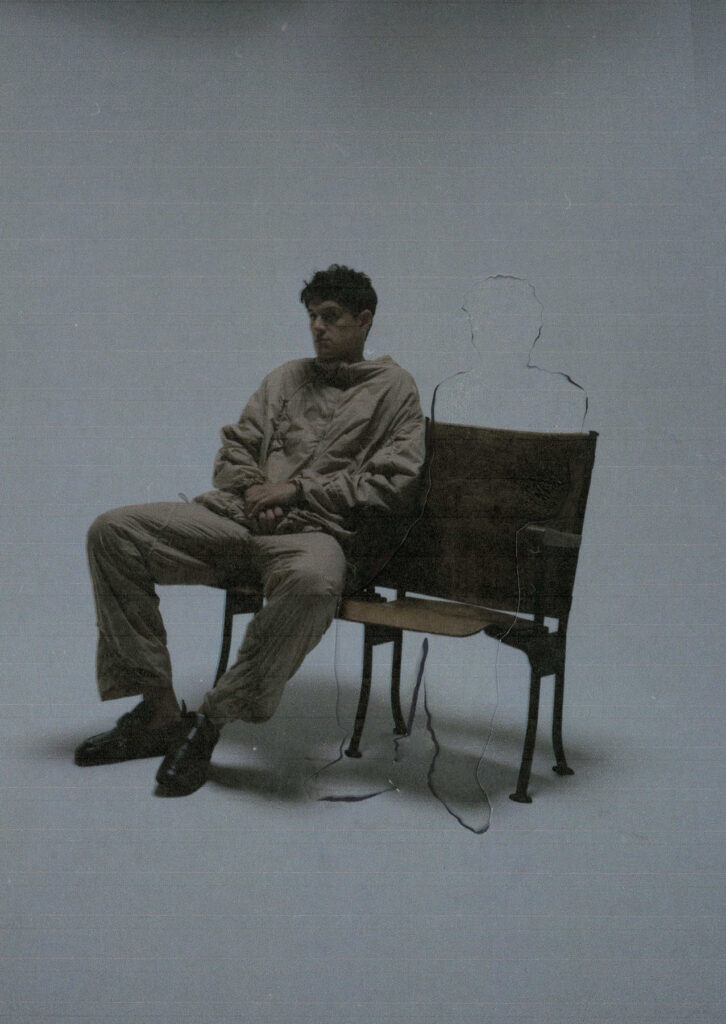

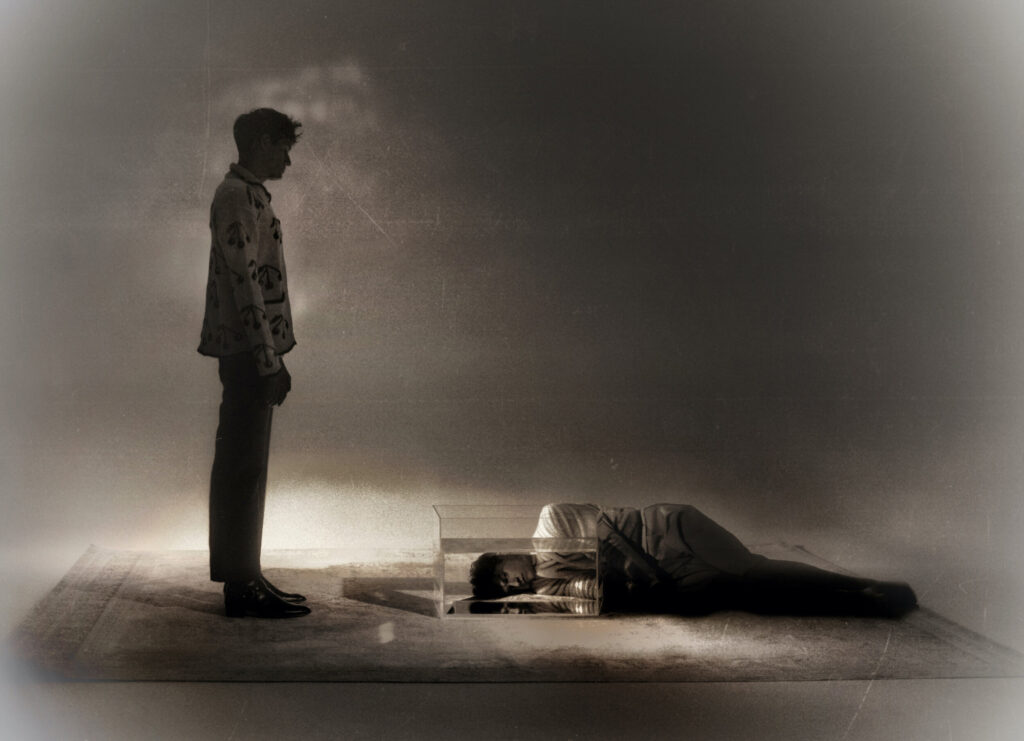

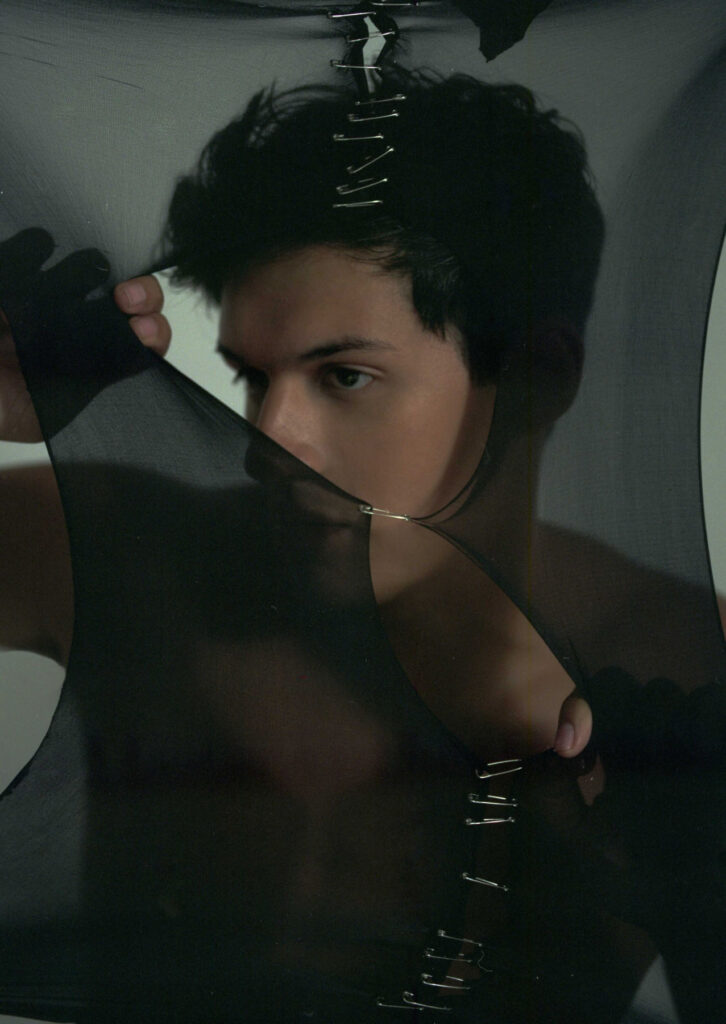

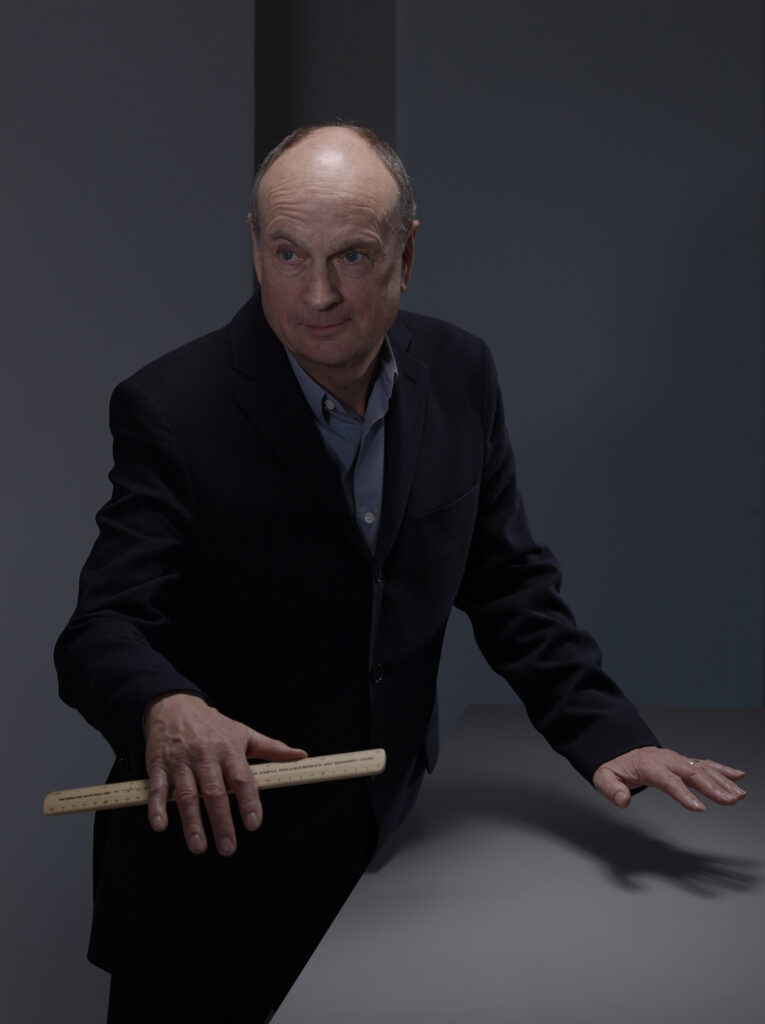

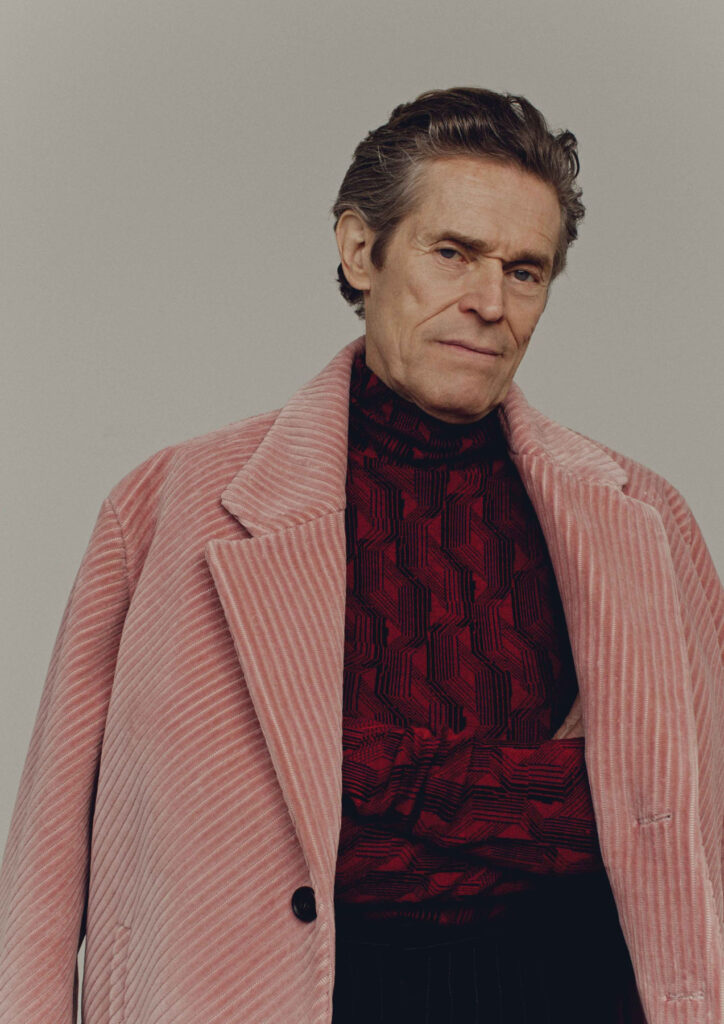

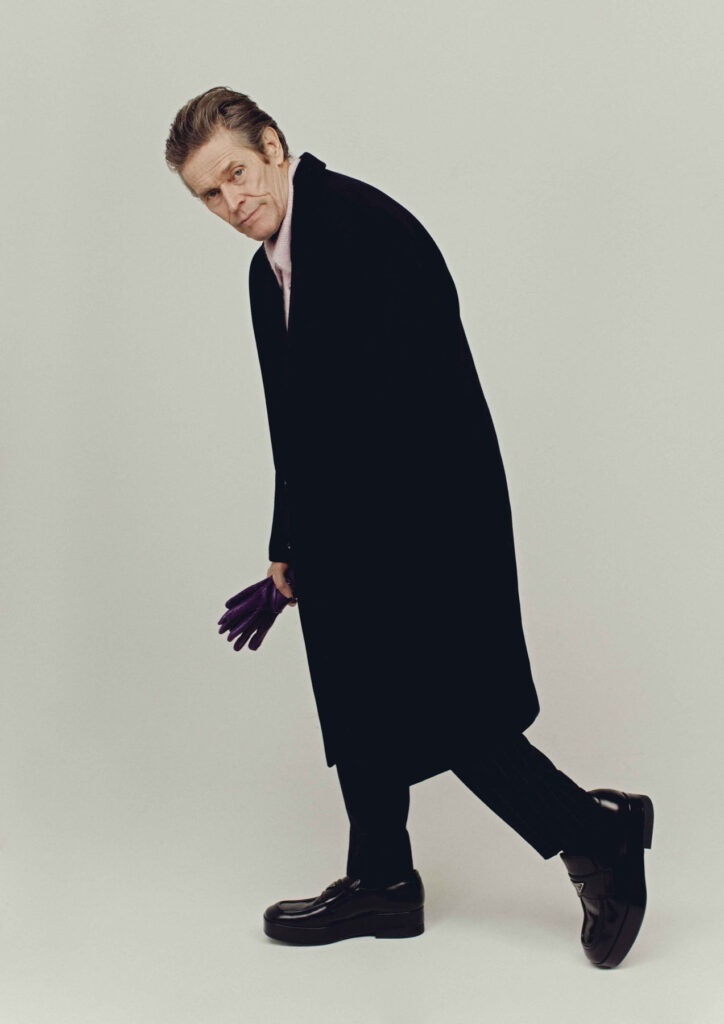

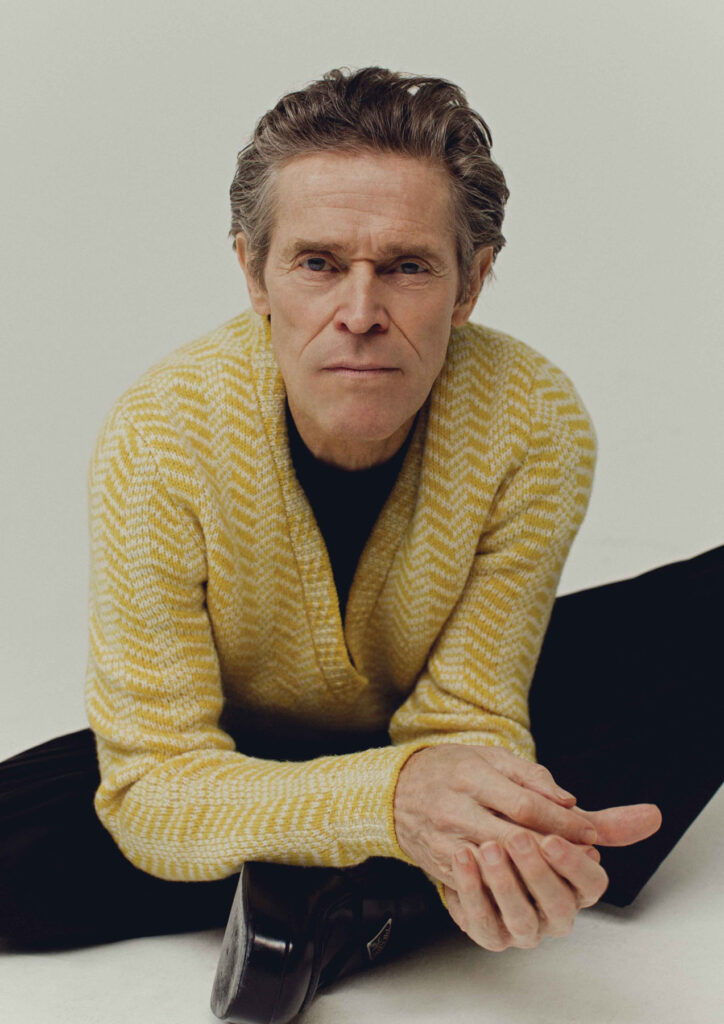

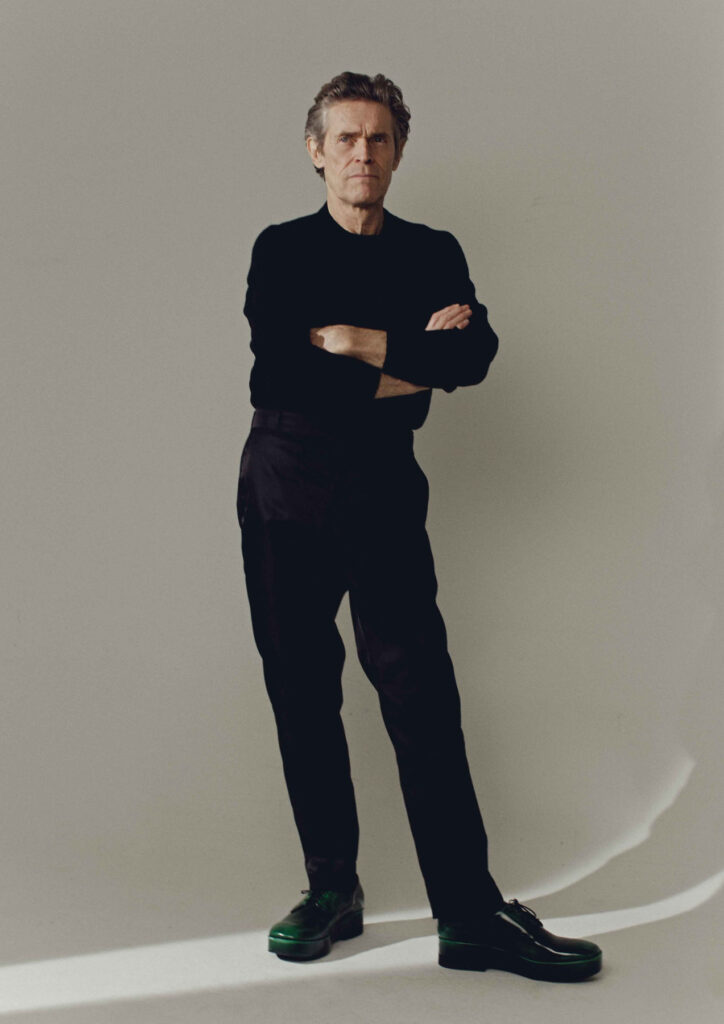

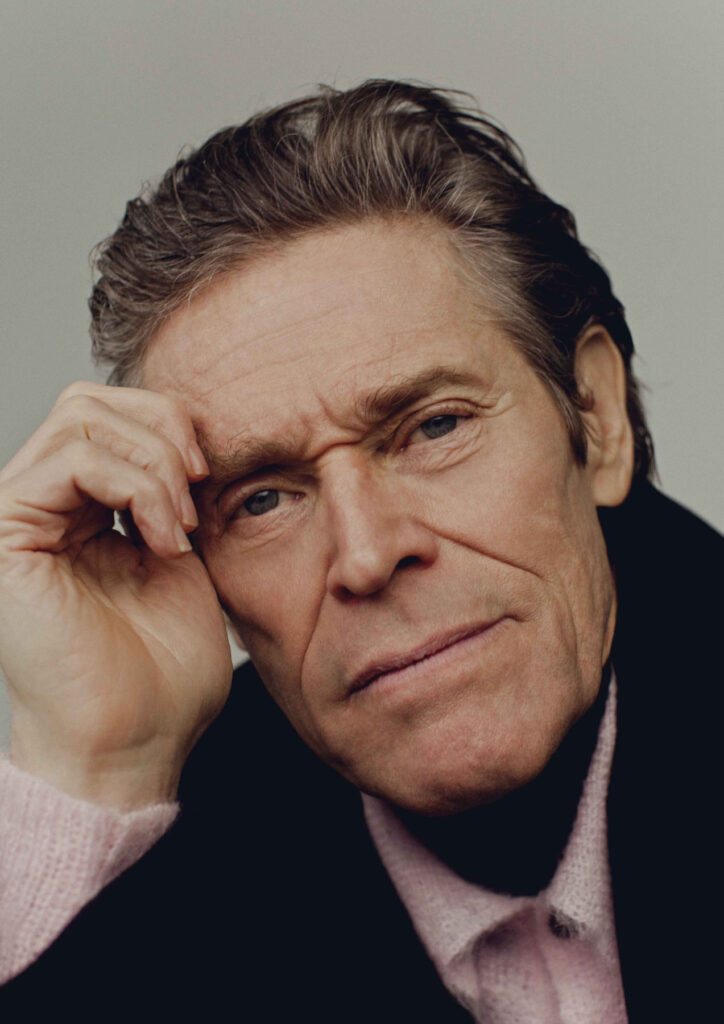

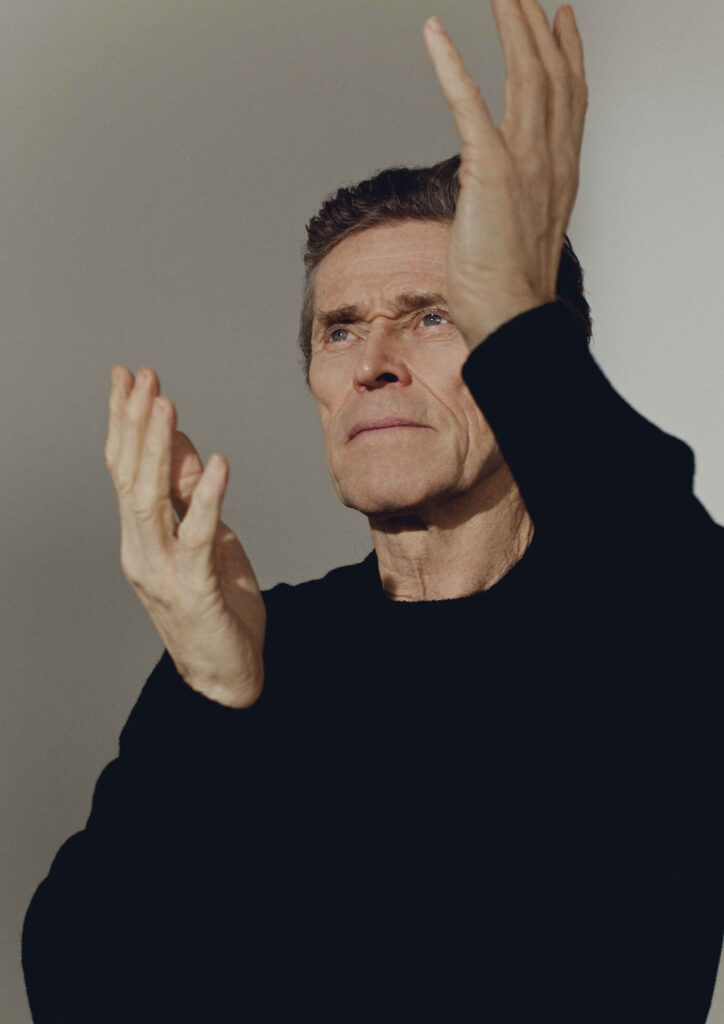

Willem Dafoe connects to Zoom from Rome, where he lives with his wife, Giada Colagrande. The actor has just returned from filming in Budapest – where last week, the shoot for NR took place. For the shoot, Dafoe wore exclusively Prada, a brand he says he likes very much. “There were some crazy colours, but I like to stick out my neck a little bit. Sometimes I put on clothes I wouldn’t normally wear in life, but I enjoy doing it to shoot with.” As one of the most prolific actors in cinema for some forty years, the actor must have some familiarity with stepping into clothes he might not otherwise. “That’s the idea, and that’s the pleasure,” he says. Whether he steps into Prada attire for a magazine or spends countless hours in make-up to embody the legendary Nosferatu in 2000’s The Shadow of the Vampire, Willem Dafoe is a master of using costume and his surroundings to capture the emotional profile of a character.

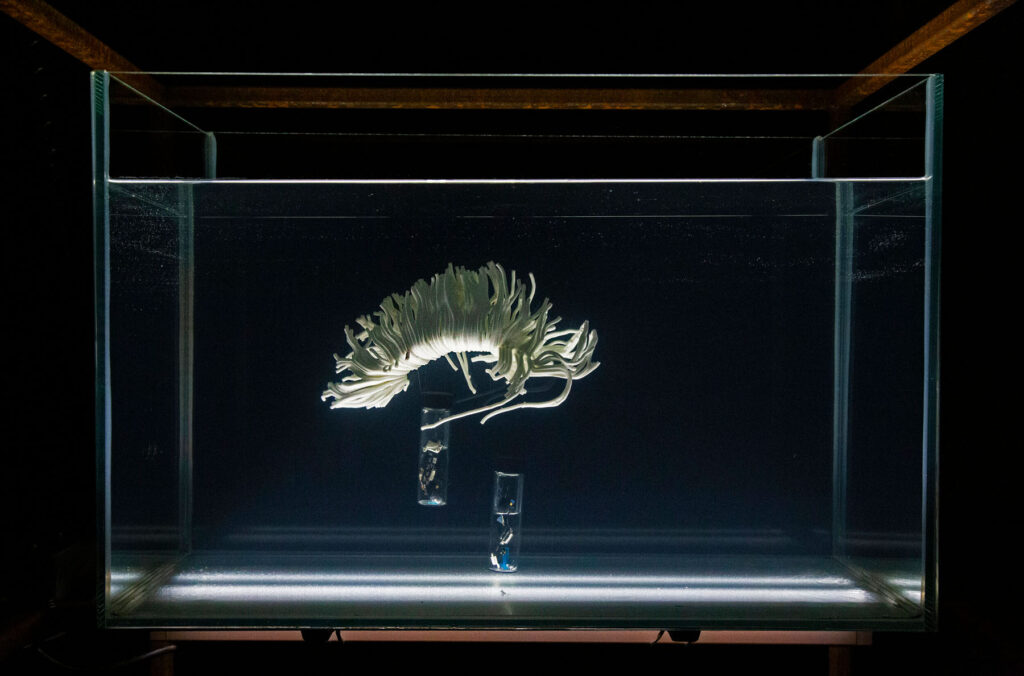

And his characters are vast and varied. The actor has played a red cap-wearing ship engineer in Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), a weather-beaten lighthouse keeper in The Lighthouse (2019), and as Sergeant Elias in the career-launching 1986 film, Platoon. From voicing the world-weary Gill in Finding Nemo (2003), to courting controversy through association with Lars von Trier’s provocative arthouse films Antichrist (2009) and Nymphomaniac (2014), Dafoe’s career is difficult to pin down. It’s not surprising, given the kinds of roles the actor has undertaken, that he is often asked if he has difficultly in leaving his characters behind. The answer is no, he can shut them out and return to his life, being Willem Dafoe, without problem. But are there elements of characters, perhaps some more than others, that stick with him regardless?

“When I do a project, I have an experience. It’s part-social, part-artistic, part-life experience, and you learn things,” he explains. “When I learn things, I don’t unlearn them – unless I really make a concerted effort to. So certain things do stay with me, or certain things surprise me.” That, for Dafoe, is part of the adventure and the pleasure of stepping into the shoes of a character he hasn’t previously met. “Other possibilities occur that didn’t occur before in your life,” he adds, “like new skills or different sensibilities. “Those are the things that stay because I return to that feeling.” Besides the lasting impact that playing a role can have on Dafoe as a person, I wonder if he ever looks back to a previous character in order to shape a new role? “I hope not! You know, the idea is really to start from zero every time.”

The reverberations of previous performances can linger, but Dafoe is careful to avoid revisiting the past. His process involves “trying to steer away from that, not to repeat yourself – not that that’s a sin, but it might suggest that you aren’t going deep enough, or you’re leaning on something.” Delving into the unknown is where Dafoe finds his energy. The actor has also made a career-long effort to avoid being typecast. Despite his distinctive face and a persisting misconception amongst some that he almost exclusively plays ‘bad guys’, it’s difficult to see the same person twice across his oeuvre.

The surface characteristics of a role are something that Dafoe specifically tries to mix up, in order to avoid repetition. “Sometimes I’ll approach a character and look for a trigger for your imagination – so I’ll change my external appearance in some way.” That might be a prosthetic or a hairstyle. It might, for example, be a moustache. “The style of that moustache, in my head, is owned by a certain character, so if I have a moustache that looks a certain way, I think ‘Oh – that’s too Bobby Peru!’”

Dafoe has spoken previously about playing the lecherous gangster Bobby Peru in David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990), recalling that the director handed him the character’s costume without discussion. How much of the process of bulking out a character is a collaboration? That depends on various factors: the character, the project and the personalities involved. Part of what Dafoe calls the “beauty of working in film” – and to a degree, in theatre too – is that “one must figure out what they think their area to explore is, their area to perform in, or what their responsibilities are.” Those boundaries aren’t fixed, but perennially shifting. “Sometimes one has to support other aspects of the story to get it on its way; sometimes you are the story.”

“And in a similar way, some directors want talent to collaborate, [while others] want their actors to inhabit what they’ve created.” In At Eternity’s Gate, the 2018 biopic of Vincent van Gogh, director and painter Julian Schnabel taught the actor how to paint in preparation for the role. Writing in The New York Times in 2020, Schnabel recalled how early scenes from filming didn’t make the final cut: “He was wearing the same clothes, had the same hairdo, but he wasn’t the guy yet. Then there was a certain moment when all of a sudden he was. He was transformed, transfigured. He was somebody else.” Dafoe says that he likes a flexibility of approach in order to not take himself too seriously or get stuck in the belief that there’s only one way to go about the acting process. “It makes me feel more fluid and energetic somehow.” Figuring out how to navigate a role or a collaboration is also where the pleasure lies. “Once I feel comfortable in that mode and I’m working with people that I trust, then the sky’s the limit.”

Dafoe’s response intrigues me, in part, because of an interview he did with fellow actor and Mississippi Burning (1988) co-star, Frances McDormand for BOMB in 1996. “That’s another age!” he exclaims. It is, but there is something he says that is particularly interesting. In the interview, Dafoe refers to actors as “serving someone else’s construct,” before asking McDormand the extent to which she finds that position frustrating or liberating. In 2021, how would Dafoe respond? In order to answer, he asks what McDormand replied. I can’t remember, I confess. But going back to her answer – that “actors are in the service industry” – it is undoubtedly similar to Dafoe’s. “Part of an actor’s process is serving [the] idea and being able to articulate and inhabit what [the director] is trying to do.”

“I think I say this a lot,” Dafoe continues, “so maybe I’m getting stuck in a certain kind of idea, but I still think it’s true – it probably was true in 1996 – when you aren’t trying to accomplish something that serves your goals and you start to consider some else’s point of view, that becomes creative and that becomes fun.” In doing so, one is “let of the hook” in a way because the actor is not responsible for the film’s meaning, or its framing. “But the quality of being there, of what someone is doing, and the pretending is an actor’s responsibility – and I can do that if I’m doing that for someone else. If I’m doing it for myself, I sometimes have a little voice in the back of my head that’s always asking how I’m doing; ‘Is this what we want?’ ‘What’s this going to get me?’ And you want to get away from that.” To let the experience wash over Dafoe in this way allows him to “feel looser and more open,” and to forget himself in that moment. “You’re not there anymore, you’re someone else. And that taps you into a whole other world that’s not based just on your experiences and the things you want.” It’s in that state that allows for “something pure and intuitive – beyond your understanding,” shutting out a self-consciousness that can (dis)colour the action. “That’s usually where the most interesting things happen.”

Dafoe may be deemed one of Hollywood’s leading actors, but he rarely appears there – preferring films shot on location. In the case of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Dafoe headed to Morocco to film, only to return to the US to encounter a backlash. The actor’s all-too-human portrayal of Jesus was deemed blasphemous by some religious groups, but it demonstrates the extent to which Dafoe seeks out real emotion during the filming process. “Shooting on location is a lot of fun because my life experience working in that place informs [and roots] what I am doing.” In a more extreme way that some of Dafoe’s other films, The Last Temptation encapsulates how the environment and emotion interact in order to shape the character that appears on screen.

In Sean Baker’s critically acclaimed 2017 film, The Florida Project, Dafoe plays Bobby, the overstretched but unflappable manager of the Magic Kingdom motel on the periphery of Disney World, Florida. Filmed at a functioning motel, many of the film’s stars were, unlike Dafoe, non-actors. In order to master his role, Dafoe learned the ropes of management from the Magic Kingdom’s real-life manager. It catapulted Dafoe into another world, shaped by the surrounding characteristics and quirks of the location and its weather system, the lifestyles of its inhabitants, and so on. “I spent my time working with people that are actually living there, so it’s super rooted. Hollywood does not exist for these people,” he explains; “after a couple of days, they’re over the fun of the circus coming to town [and] it becomes life for them. And also, for myself.” If that made the film’s situation “easier to enter” for Dafoe, it also contributes to the uncomfortable truth portrayed in the reality of the characters and their experiences.

Then there’s the overwhelmingly morbid The Lighthouse by Robert Eggers, in which Dafoe and Robert Pattinson feature as two nineteenth-century lighthouse keepers on a remote island in New England. Shot in black-and-white in square format (recalling the silent films of the previous century), the film is uncomfortably claustrophobic. The lack of theatrics gives The Lighthouse a terrifyingly real atmosphere – except for very brief uses of special effects that blur the realm of ‘real’ versus ‘surreal’. “The isolation was so complete,” Dafoe recalls; the film was shot in Nova Scotia under terrible conditions. “The weather was so extreme that that put us there right away. There’re certain things that are very difficult to act, you know, extreme cold, runny noses, flush skin from brutal wind. These kinds of things put us in a state that allowed us to be there in a very full way.”

The strife and struggle that burdens Dafoe and Pattinson is rendered visible by the circumstances under which they filmed. Not least, as Dafoe adds, in the moment of filming something like The Lighthouse “I’m not thinking about how the movie is going to do. I’m not thinking about my career. I’m not thinking about any of these things because I’m in it.” Shooting on set, meanwhile, is fundamentally different. “I go into make-up [and] there may be movie magazines around, which I don’t like very much because I don’t want to be reminded about those kinds of things when I’m making a movie.” Inasmuch as Dafoe seems to resist the ‘cult of the movie star’ when it comes to being an actor, though, it’s inevitable that he cannot always control how he is perceived.

Given the nature of some of the characters the actor has played, I wonder whether other’s perceptions of him, as Willem Dafoe – the person, are shaped by a particular film role. And if so, which characters tend to be referenced the most? “You know, I can tell. I can tell what films people have seen when they approach me.” Because Dafoe has undertaken so diverse a range of roles and films, it’s easy to demarcate one type of movie watcher from another. He says that he often feels that people who watch the higher-pace films have “no awareness of the European movies or the auteur movies, and vice versa. Someone will come up to me and say, ‘I’ve seen all your movies,’ and they’ve probably seen 10%.” That’s normal; it’s a reflection of different tastes. “Spider-Man, The Lighthouse or The Florida Project – those are three distinctly different movies.”

The actor has identified, for example, a middle-aged audience who watched his earlier films before getting caught up in life as they got older; “they stopped watching movies and if they did, they tend to go to the more available, the more commercial. They were less cinephile.” So, there are different camps of the Dafoe-phile (‘fandom’ does not seem to be an appropriate way to describe it). “Sometimes you see people that are stuck in another time of your career because it reflects their viewing habits. People do see you depending on the films they watch and the characters they see.” It’s curious how this then feeds into preconceptions about the kind of person Dafoe might be. “Some people think I’m, you know, some crazy nut. Some people think I’m eccentric. Some think I’m a normal guy. Some people think I’m athletic. Some people think I’m an old guy.”

Dafoe talks compassionately about the encounters people have with him. He recognises that the interaction is not always specifically to do with the actor himself, but rather the characters he plays, in order for people to make sense of themselves. “I am touched by people’s need to make some sort of connection, and when they see actors and films, it connects to some prior feeling or experience they’ve had.” In that moment, “that world in their head came together with that world that was up on the screen.” Talking to Dafoe, however, he seems to embody neither the Green Goblin who lurked in the corner of my bedroom for some time after the release of Spider-Man in 2002 (“yes he is – so behave yourself”), nor does he have the pained visage of van Gogh, battling demons in his latter days, as in At Eternity’s Gate. Instead, wearing black-rimmed glasses and Bose headphones, Dafoe appears to be, well, himself. The actor’s portrayal of van Gogh is one that, nonetheless, leaves a lasting impression.

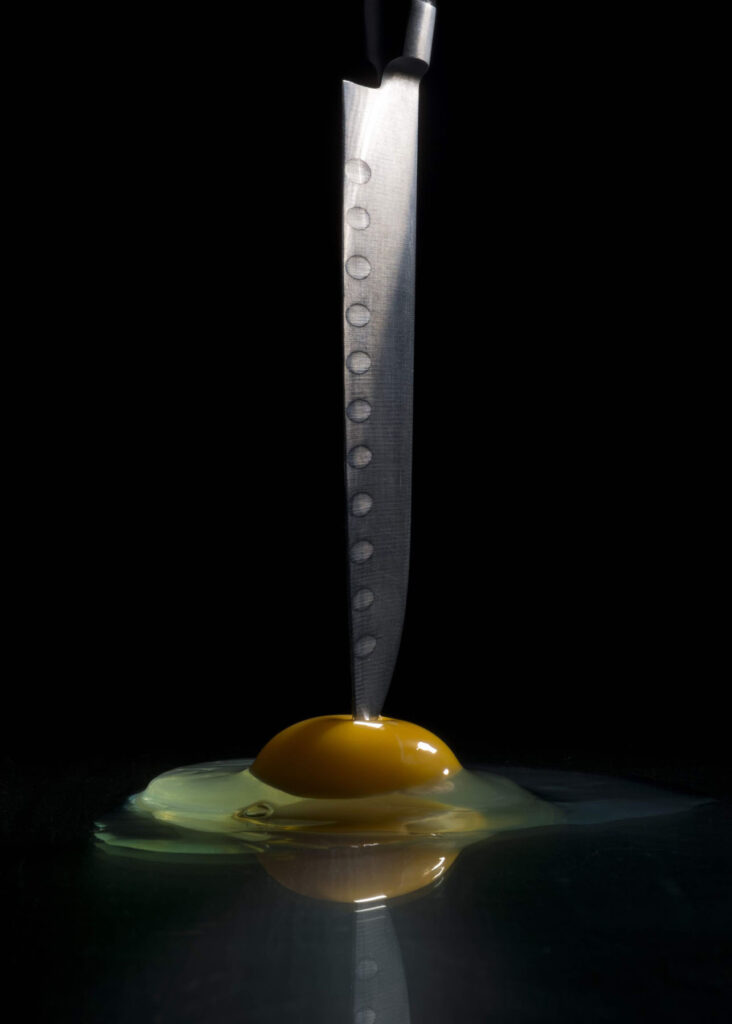

In Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 biopic of the French painter, Lust for Life, Kirk Douglas takes on the role of the ‘tortured genius’; the artist misunderstood by his peers, only to be discovered in death. The enduring legacy that exists around van Gogh created the appetite for a depiction of the life and suffering of an artist in a film like Lust for Life. But in Dafoe’s portrayal, what is so compelling is not its ‘authentic’ depiction of ‘true’ events, but his haunting portrayal of human feeling. In one scene in which Dafoe’s van Gogh explains how he cut off his ear, it isn’t the uncanny recreation of the artist’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear that makes it such an affecting scene. Rather, it’s Dafoe’s arresting ability to convey a person caught between certainty and confusion with pained restraint.

But by playing a real artist, with whom the world ‘identifies’, some criticism is inevitable. Over the course of a career defined by such a range of characters – real (a motel manager), ‘Real’ (van Gogh and Jesus Christ) and fantastical, where does Dafoe locate and connect with the essence of a character? And how does he decide whether or not to take up a role? “I read a script and I say, “What does the person do? Do I want to do those things? Am I interested in them? Will it be fun? Will I learn something?”

The pandemic allowed Dafoe the chance to stop temporarily and spend time with his wife, Colagrande, who as a filmmaker and musician has a schedule to rival his own. Dafoe scrambled back to Rome from New York and recalls how volatile and scary those early days of the pandemic were. There was the aggressive jockeying in the run-up to the US election, misinformation surrounding COVID and the point of view that Italy was, besides China, the “worst place in the world to go”. By July, however, Dafoe was able to get back to work, something that he says he is grateful for. The circumstances, though, were different. “The idea before Nightmare Alley [director Guillermo del Toro’s forthcoming carnival-based thriller] of spending two weeks on entering Canada in an apartment unable to leave, having your food delivered to you, was basically like prison – actors’ prison.”

If the pandemic slowed down Dafoe’s usually busy schedule, the actor is now regathering pace. And Poor Things, based on the 1992 novel of the same name by Alasdair Gray, is one project that is worth keeping an eye out for. “Listen, it was a great experience and Yorgos Lanthimos is a real talent. It’s got a beautiful cast, and you get self-conscious. I don’t want to blow my own horn by association saying how great things are, but it’s very special.” Given the nature of the story, it will be fascinating to see how it is realised on the big screen. Dafoe is, equally, intrigued – but shuts himself up before sharing any potentially revealing details. “Since I just finished, I’m still high off the experience. I’m excited about many things, but this one is high up on the list.” I don’t ask Dafoe whether the rumours are true that he will be resurrecting the Green Goblin for this year’s highly anticipated Spider-Man: No Way Home; he certainly wouldn’t tell, and, for the sake of my younger self, I don’t really want to know.

Credits

Creative Directors · NIMA HABIBZADEH AND JADE REMOVILLE

Photographer · LUC COIFFAIT

Fashion Stylist · SAM CARDER

Grooming · VIRAG MOGYORO

Assistant · ALEXANDER CSOMOR

Interview · ELLIE BROWN

WILLEM DAFOE WEARS PRADA AUTUMN WINTER 2021