Rick Schatzberg grew up in a suburb of Long Island in the 1950s – a place constructed out of nothing but a post-war optimism for prosperity and abundance. A place that, by Rick’s own admission, was in reality, characterised by its monotony and it’s ‘nowhereness’. Surrounded by the comfort of middle class living, Rick and his friends discovered the world by hanging out in one another’s bedrooms, the local mall or a wooded area not far from their suburban enclave. As teenagers, the boys (as they came to be known amongst themselves) would experiment with alcohol and drugs, and hang out with girls; an upbringing unremarkable to anyone who wasn’t there at the time. As they grew older, the boys took on different careers. Rick moved to New York and became an entrepreneur, the others would become teachers, taxi drivers, salesmen, realtors and healthcare workers But they remained what Rick calls a ‘cohesive entity,’ eternally bound together by their childhood moniker.

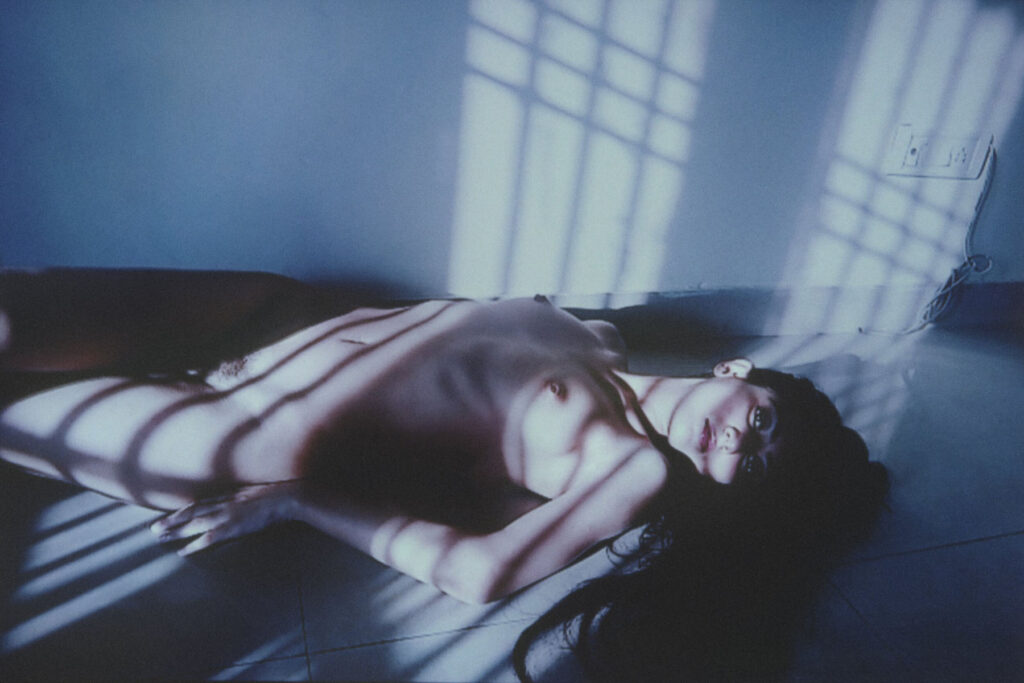

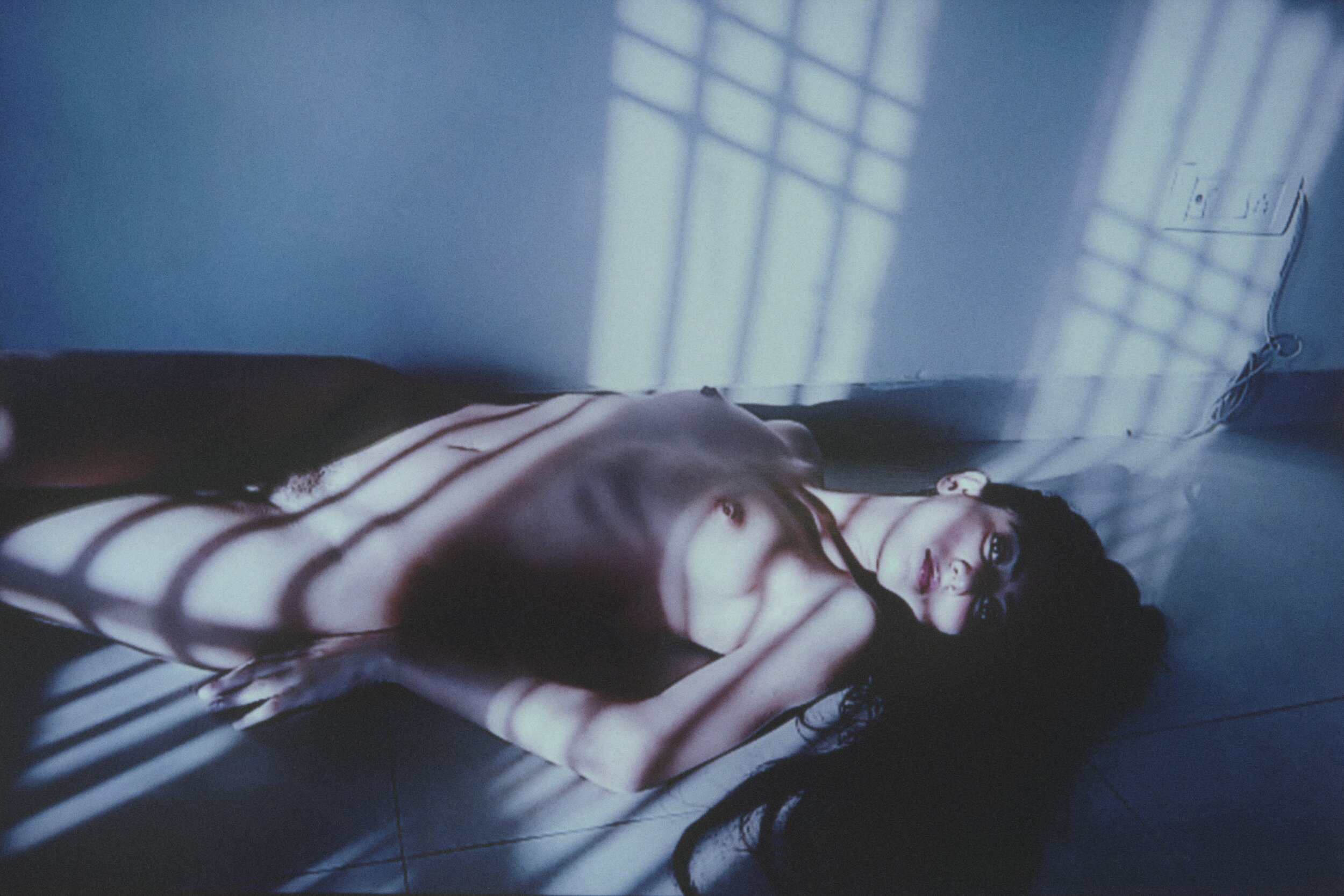

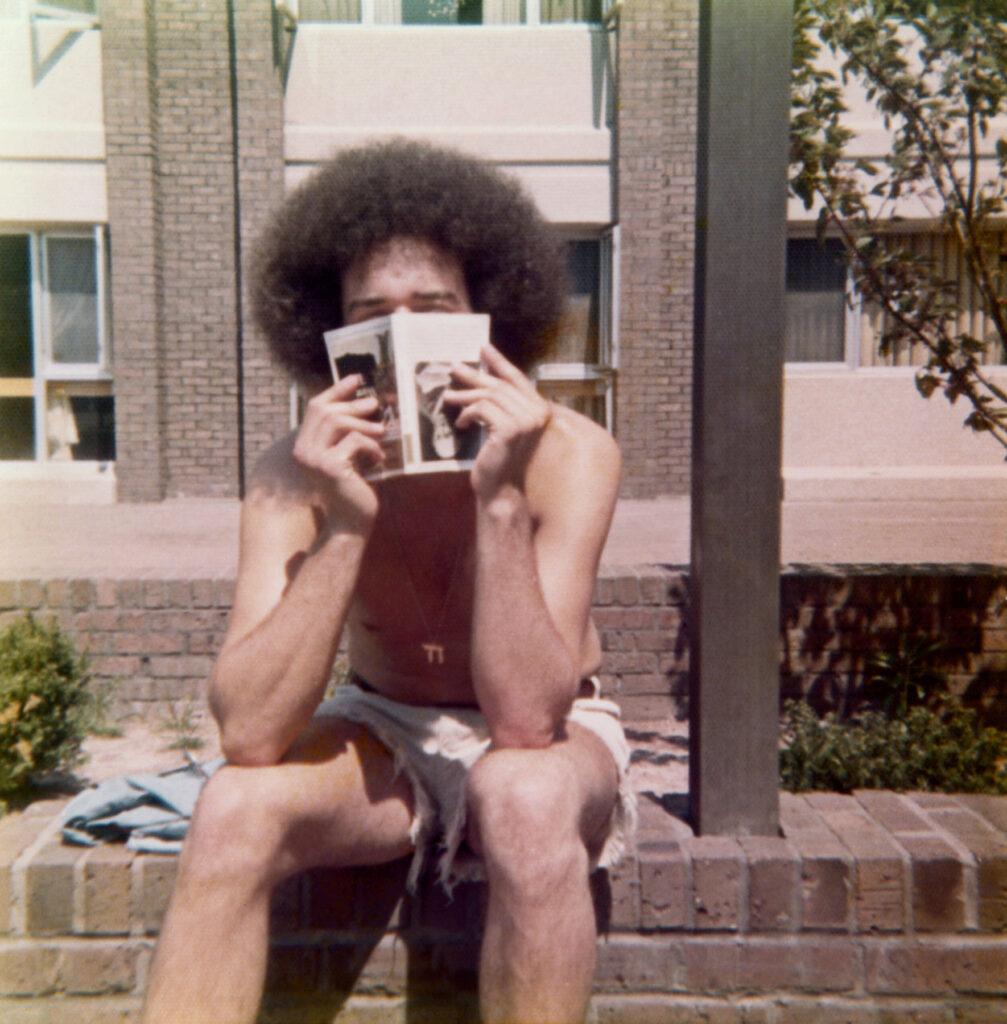

The Boys, the second photobook by Rick Schatzberg, is the result of both his pivot into photography and the unexpected death of two of his friends in close succession. Confronted with the fragility of life, Rick began in earnest to take photographs of the remaining boys. Using a large format camera, the images of himself and his friends, now in their mid-60s, are a stark reminder of the passage of time. In and of themselves, Rick’s photographs are tender portraits capturing the toll of time and age on the human body. But in the book, these images are interspersed with snapshots and photographs from the boys’ youth. Aged bodies become youthful, smiling faces – hanging out, experimenting with weed. Though Rick is quick to outline that The Boys isn’t nostalgic, there’s something poignant in flicking through the book’s pages and recognising the quirks and characteristics of each of the boys as time passes by. Addressing the responses he’s had so far about the book, Rick sums this feeling up well in our interview below: ‘anemoia: nostalgia for a time or place you’ve never known’. Many of the old photographs included in the book are snapshots that had been forgotten about – forgotten in the almost immediate aftermath that they were taken. They raise questions of memory; can the boys even recall the time and place that the photograph puts them in?

Alongside the images, old and now, are twelve short texts. One is an email exchange between Rick and two of the boys trying to piece together the facts of a fight that happened at a wedding. Their recollections of what actually occurred differ; evidence of the unreliability of memory. To celebrate the release of the book, Rick spoke in conversation with the photography writer and curator, David Campany in early 2021. As well as discussing the subject matter of The Boys, something that came up as crucial to the book’s release is its design. As part of the book launch, Rick shared a video of himself going through the book to demonstrate that the large format photographs of his friends feature as fold out pages (something, he tells the audience via Zoom, his mentors and peers from his photography course advised against). But something that also stands out in the structure of the book is that the 12 texts Rick includes in The Boys read like snapshots themselves.

An accompanying essay to the book by the writer, Rick Moody, raises this point, writing about the ‘relationship between a still image and the kind of expressive power that we associate with narrative activity.’ In the context of The Boys, as a photobook, this takes on historical significance. Writing about the 1920s, a time of the proliferation of the photobook and the photo essay, the academic Andreas Huyssen describes how a new form of literature appeared.

The “modernist miniature”, popularised by novelists like Franz Kafka and critical thinkers like Walter Benjamin, sought to capture modern life with photographic precision through words. In that way, then, Rick’s book is much more than a selection of photographs of his peers – young and now old – it’s a reckoning with how we navigate time, memory and our existence through the lens of modern life.