“The driving force behind both temporary and permanent work is similar; it’s about the performance.”

Dutch architect Anne Holtrop started his eponymous studio in 2009. Anne designed the Bahrain pavilion for the World Expo in 2015, without having visited the country beforehand. Now, the architect divides his time between his hometown, Amsterdam, the Kingdom of Bahrain, where he is working to refurbish heritage sites, and as a Professor of Architecture at the ETH in Zürich, Switzerland. Anne’s work spans temporary installation to permanent structures, but it is his use of tactile and organic materials for which the studio is both recognised, and recognisable. Having started out as an assistant to Krijn de Koning, the Dutch artist known for his site specific installations, Anne’s first project was the Trail House in Almere. As part of an exhibition by the Museum De Paviljoens in 2010, the installation consists of a series of paths that make up the house’s structure – described as ‘A house that curls, bends and splits through the [vegetal] landscape’ surrounding it.

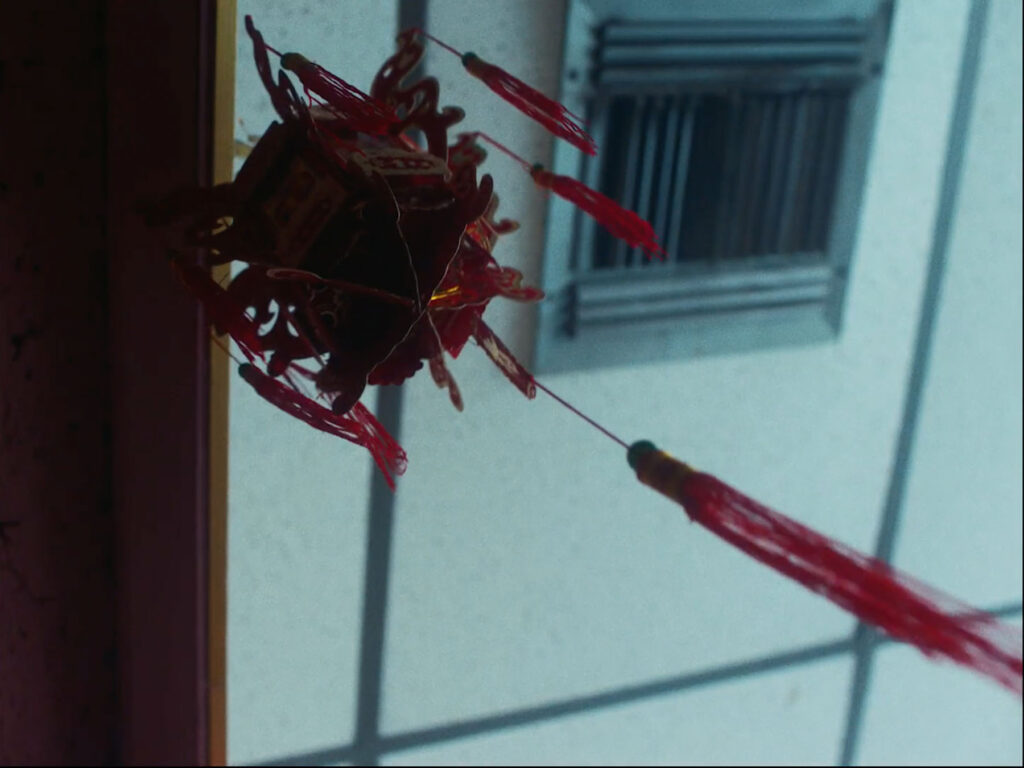

Alongside his work in Bahrain, Anne has worked with John Galliano since 2018 to redefine the brand identity of the Parisian fashion house, Maison Margiela – culminating with the remodelling of the label’s London store earlier this year. The curved gypsum walls and fabric-cast surfaces are evocative of both the studio’s signature feel, and of Margiela’s recent in-store presence. But, as Anne explained over Skype back in February, his work process is limited to neither the studio, nor Galliano’s vision for Margiela. Rather, he heralds the disappearing craftsmanship of specialists and family-led artisans. ‘For Margiela,’ he explains, ‘almost everything is produced in Italy. Around the time I started working in Bahrain, I started working a lot in Italy with small workshops that were specialists in the different materials I’m interested in.’

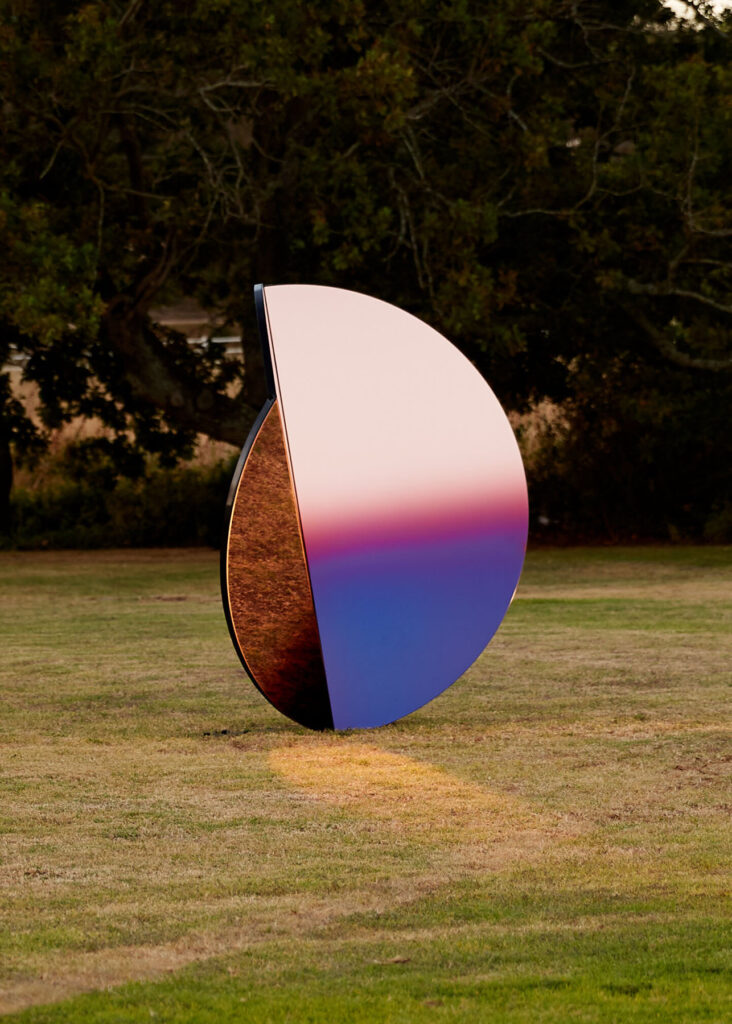

The gypsum casting that embodies Anne’s work with Margiela? It comes from a small company in Veneto; the profession almost died out, I’m told, because house molding is no longer en vogue. When Anne started working with the company, they had only two employees; they’ve since re-hired former collaborators. That’s not to say that irreparable damage hasn’t been done to artisanal craftsmanship though; despite enjoying something of a renaissance in recent years, Anne is quick to point out that ‘because of our lack of interest for a long time, these industries, which are often small family-based companies, have died out.’ The aluminium that features in the Green Corner building in Bahrain (2020), was cast at a foundry in the Netherlands, where their specialism allows for the experimental techniques that Studio Anne Holtrop employs.

Central to Anne’s design approach is an innate belief in the ‘gestures’ that define materials; the source of those very materials, and the ways in which they’re used to construct spaces and the architectural environment. And as our conversation below demonstrates, these are themes that inform Anne’s vision for the temporary, the interior and the exterior.

Does your practice take on different approaches depending on whether you’re creating something temporary versus a permanent?

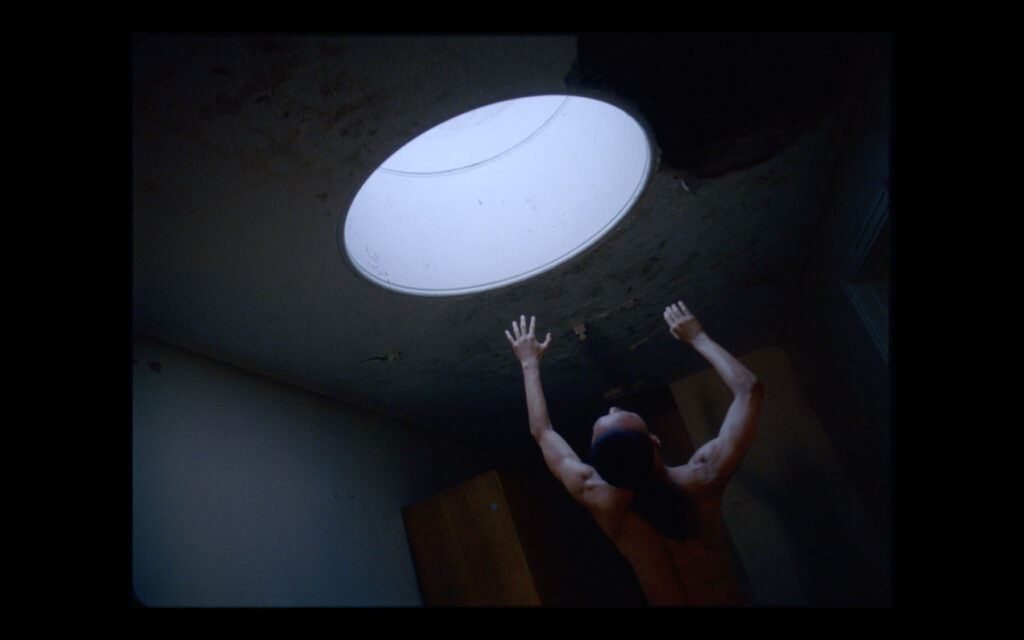

With [Maison] Margiela, we did a catwalk show in 2018, shop windows in Osaka and a pop-up store in Tokyo. So these exist for one week, one day, a month – and in architecture, that’s a very short time. What I like about temporary work is it can be more radical in a way, because we have less to fulfil for a permanent use. So for instance, with Margiela, the [display] in the shop windows in Osaka, we made them out of very thick felt that we let hang. So it was a kind of architecture that’s literally soft; that has no rigidity. To make architecture that is literally soft is very difficult to maintain or to use. Although Margiela would love that idea, the practicality of it is just more difficult to manage. The driving force behind both temporary and permanent work is similar; it’s about the performance. You know, how can we form space and how can we also discover space?

The Margiela store in Paris has crooked columns (textile-cast gypsum), which was a process of making, where we deliberately searched for an undefined outcome. It redefined the process of making, and the outcome is different every time you produce it. In that sense, we can discover and invent spatial conditions. John Galliano describes this kind of pyramid where everything starts with the artisanal collection, and then it trickles down. With architecture, we build maquettes of projects with the materials that we want to construct with. So that’s also a kind of temporary building – to scale, but it exists. It has a reality. Even if a project is permanent, that’s its temporary state.

I was looking at images from your work with the Charlotte Chesnais jewellery store in Paris from late last year; the acrylic sheets you use have these really organic shapes. I’d love to know a bit more about the kinds of materials you work with, and how you translate these into organic forms?

I have a liking for irregular forms like the Rorschach inkblots, the butterfly inkblot tests that are basically just ink on paper. But because of its form, you imagine things in it and for me, the irregular or organic forms of things have more possibility than a purely rectangular form. You can project more into it. That’s the way that we work because we have form that is not necessarily architectural. So, we can start to imagine how we’ll use something; how can we read the architecture? And for visitors, that happens [all over] again.

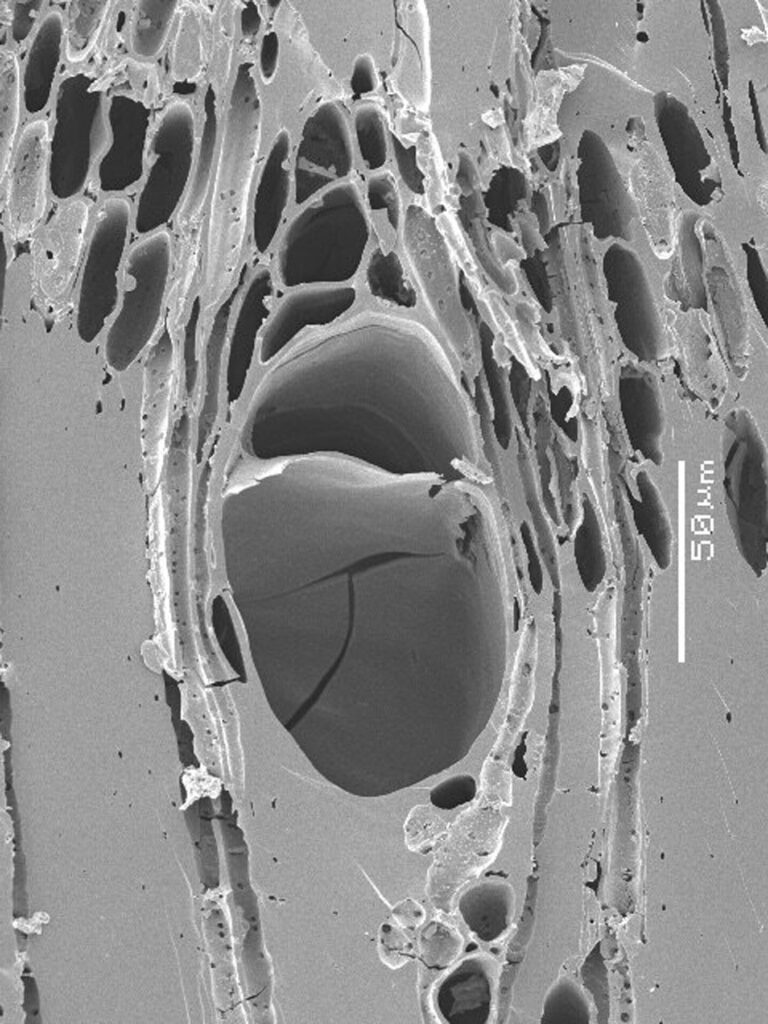

With the Charlotte Chesnais store, [the approach] came from a project before that, where we started casting materials directly in sand, using sand as a natural relief. So we cast another material in it and it takes the imprint of it in the material. We started doing that with gypsum, concrete and aluminium. For the store, we used acrylic but we didn’t cast it; we scanned a 3D relief of the sand. The irregular relief diffuses the light a lot more than it would a flat surface, which works more as a mirror.

[But] the irregular relief starts to diffuse the light so you cannot see through it anymore; the ceiling has this irregular form, and that diffuses light into the space and onto the display. Then we repeated the exact same thing with the display table, which works as a backdrop for the jewellery. So with the specific treatment of a material, we benefit from certain characteristics of it. By changing the relief, we have different characteristics that we can work with. So the material is the same, but the way it is formed and treated enhances, or brings forward, other properties. That is something I call material gesture; to work with the gestures that are intrinsically bound to a material, but also the gestures that, in the process of making things, are formed with the material.

And this is the same process you used for the Green Corner building in Bahrain?

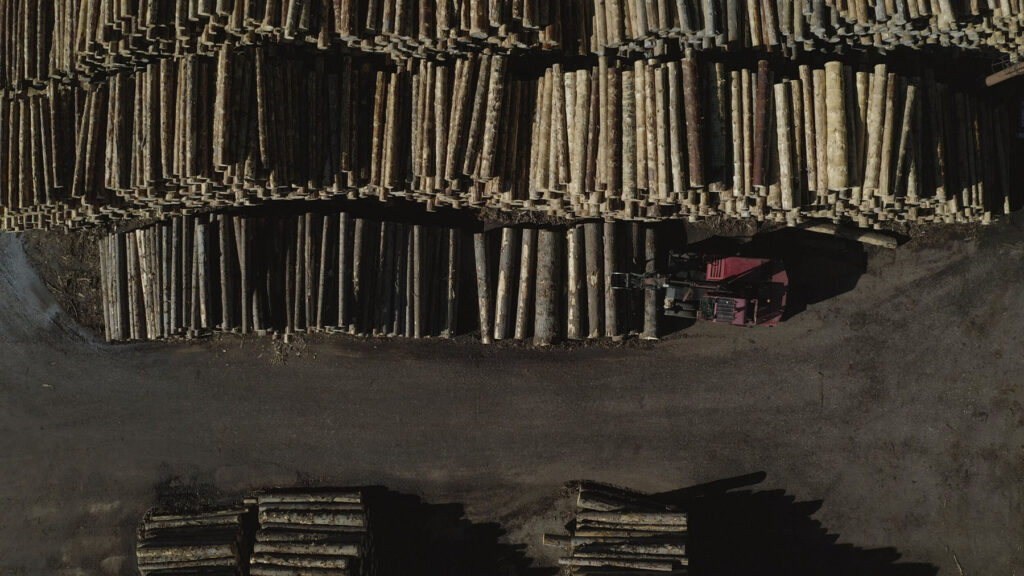

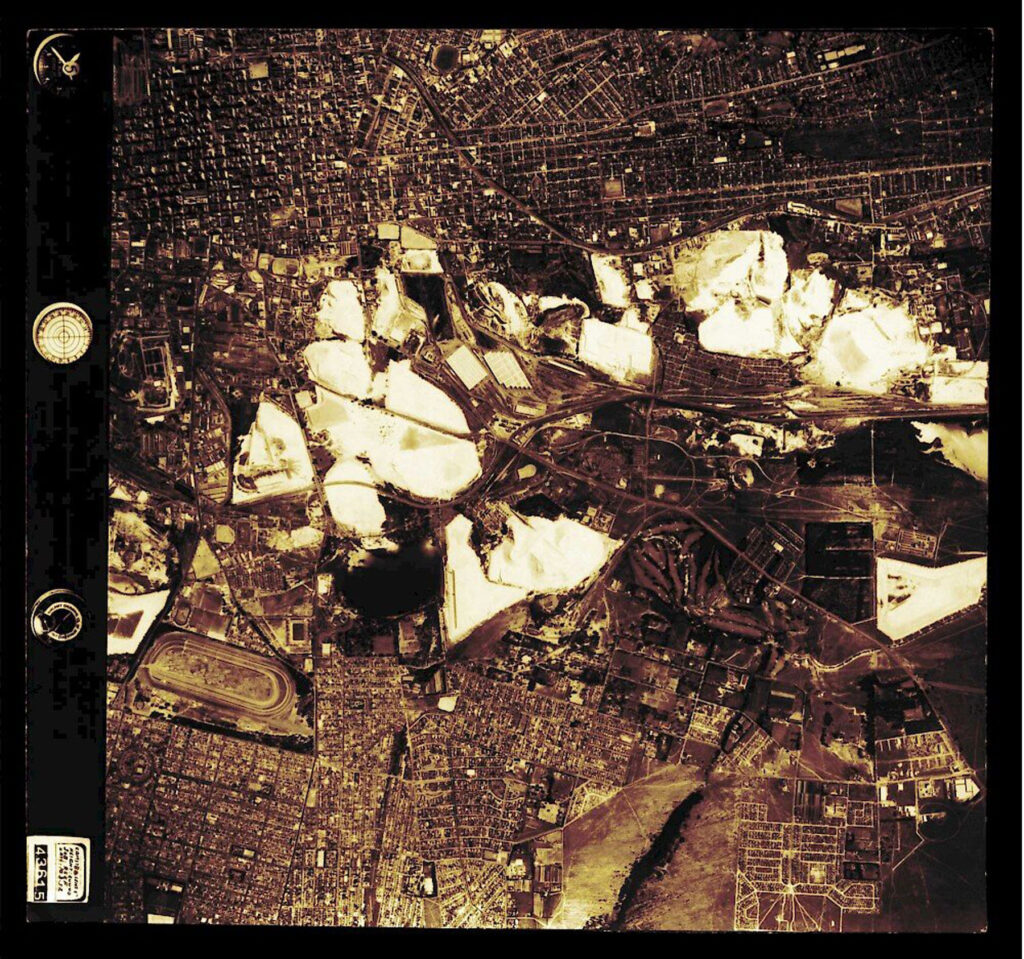

Yes – in the Green Corner building, all the concrete (so, the façades, the walls, the floors) are cast on land next to the building. So we cast it directly in the sand; every time the sand has been worked on by the workmen on the site, and so every time we had different reliefs in the concrete. It was also very efficient, so in that sense it contributes to an idea of sustainability because most of the form work is just in the sand, in the ground that is already there. We didn’t have to transport building materials, just the concrete. I think up to 50% of the energy [to build] is used in making form work, and the other 50% to cast it. So, by shortcutting that first 50% of formwork, we reduced the energy consumption used to make a building. But that’s not the only driving force.

The driving force is that we can building something that feels very local, and very [site specific]. The site itself produces the building, and leaves its mark on the building. With the façade, each one is a fragment of the landscape, but also a moment in time. One was done in March 2019, another in April. So you have this time recording in it as well. The building isn’t static; it becomes a time document and a process. With the Green Corner building, we also have aluminium doors and windows that are also sand casted, but we did that in a foundry. But with aluminium you can’t cast solids so, with the doors, the front side is an imprint of the sand and the back side is hollow.

By changing the material, you get something else. Suddenly you have the negative of the sand that you could never see in concrete. For that reason, we placed the doors and window shutters facing the other way. So when you see the sand cast concrete, you see the aluminium as a hollow version, so they are in a kind of juxtaposition with each other.

You’ve been living and working in Bahrain for seven years now – how has this time allowed you to use different techniques like, for example, the sand casting?

I mean, I was already doing that when I was [still] in Amsterdam. I was visiting Jordan, and going to Petra, a few years before I moved to Bahrain. So, for me there was definitely an interest in the type of landscape and conditions there. It’s very minimal – it’s rock and sand, and that it’s base. And I like that base because that’s also the base of building material; when I see a building standing in that landscape, I just see two versions of the same thing. And I was very excited to work in a place where I can research that kind of relationship.

So the Green Corner building is a very clear building for me in that way because it builds hat relationship between the soil in which it is built, the material, and the matter of it – the building itself and its construction.

The aluminium was also chosen because Bahrain has one of the largest aluminium smelters in the world. I saw it as being a local material, a vernacular material. When we look back in history, we say, you know, we built with clay, stones and things like that. But over the past 50 years, aluminium [has become] one of these materials. It’s a process [rather than a material], but nevertheless still part of it. And I like to build up that relationship. It’s all part of that investigation of material gesture; from the sourcing of material, the process, the craftsmanship of working with the material.